Abstract

Background

Workplace environment is related to the physical and psychological well-being, and quality of work life (QWL) for nurses.

Objective

The aim of this paper was to perform a comprehensive literature review on nurses’ quality of work life to identify a comprehensive set of QWL predictors for nurses employed in the United States and Canada.

Methods

Using publications from 2004–2014, contributing factors to American and Canadian nurses’ QWL were analyzed. The review was structured using the Work Disability Prevention Framework. Sixty-six articles were selected for analysis.

Results

Literature indicated that changes are required within the workplace and across the health care system to improve nurses' QWL. Areas for improvement to nurses’ quality of work life included treatment of new nursing graduates, opportunities for continuing education, promotion of positive collegial relationships, stress-reduction programs, and increased financial compensation.

Conclusions

This review’s findings support the importance of QWL as an indicator of nurses’ broader work-related experiences. A shift in health care systems across Canada and the United States is warranted where health care delivery and services are improved in conjunction with the health of the nurses working in the system.

Keywords: Nursing, Job satisfaction, Job stress, Quality of work life

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, the field of nursing within the United States and Canada has evolved in response to a variety of external and internal developments of its health care systems.1 The creation of new nursing positions and the increase in educational requirements for nurses and nurse practitioners’ licensure have developed feelings of role confusion and increased stress in the workplace.1 The aging and decreasing workforce not only inadequately meets the needs of the public but places stress on working nurses and government and organizational budgets.2 In addition, inappropriate funding of unsuccessful training and continuing education programs do not foster employee retention.2 If the health care systems and nursing profession do not address these developments, poor patient outcomes, an ineffective nursing workforce, and improper usage of public and private funding are of concern.

It is for these reasons that a need for reflection and criticism of interventions to improve the understanding of the QWL for nurses is needed. A broad range of definitions for QWL exist from various disciplines.3 However, most studies regard QWL as a subjective experience that is affected by personal feelings and perceptions and is related to nurses’ work environment. 4,5 QWL is related to organizational commitment, improved quality of care, and increased productivity for both the individual employee and the organization.6

Understanding the quality of nursing work life is important to the future of Canada and the United States’ healthcare systems as these findings can contribute to the improvement of nursing retention strategies.7

The aim of this paper is to perform a review on nurses’ QWL of both urban and rural nurses from Canada and the United States. This review is unique because it identifies a broad set of predictors of QWL for nurses including: demographic and personal characteristics, treatment of new nursing graduates, opportunities for continuing education, promotion of positive collegial relationships, stress-reducing reduction programs, and increased financial compensation.

Methods

Search and reporting methods in this literature review are guided by the PRISMA Statement’s publications.8

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

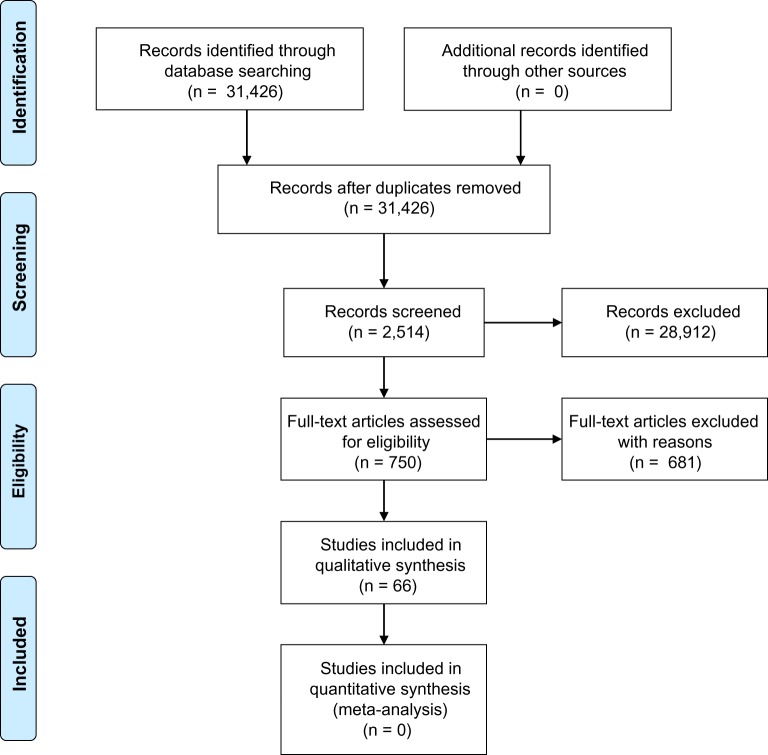

A literature search was conducted using CINAHL and MEDLINE databases. Search limitations restricted results to literature published from 2004 to 2014, in English, and in peer-reviewed publications. We then further limited findings to research focused on nurse populations in Canada and the United States. The literature search was performed between July and November 2014. The search strategy and results are summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search results

Key words used across the entire literature search included: nursing, job satisfaction, stress, work ability and retention, quality of work (QWL). The term nursing included literature for all levels of nursing registration including nursing assistants, registered practical nurses, licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and nurse practitioners.

The Work Disability Prevention Framework provided additional guidance for the literature search and presentation of findings for this review.9 While the original purpose of this model is to guide interventions to reduce workplace-related injuries, it also served as a tool to identify sources that influence nurses’ QWL.9 Therefore, the factors of each system (workplace, compensation, personal, and healthcare) were also used as search criteria.

Study selection

Our goal was to acquire five articles for each subsection of the WDP framework (workplace, compensation, personal and healthcare) for the literature review so that the results were comprehensive but focused on the most recent, relevant literature. For the former scenario, the five articles were selected by a combination of being the most recently published, focusing on a variable that was not analyzed by another article in the category, and a sample population of Canadian practical nurses or registered nurses. No article was used twice in any section in the review.

Data collection and analysis

Sixty-six articles were identified and a summary of each article’s findings was made into 15 tables based on their complementary subsection. The articles were summarized by their design, sample characteristics, interventions, and outcomes.

Each article was then assessed for biases in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved with the research team. The outcomes and biases of each article were then compared to other articles within the subsection for variability and then each subsection was compared with the other subsections within its primary system.

Results

Each article was summarized by its design, sample, interventions, outcomes, and biases within the study, and categorized by their respective findings into one the Work Disability Prevention Framework’s subsections.9 The results of this literature review are presented in Tables 1–4.

Table 1.

Summary of literature on the personal system

| Sub-system | Authors, year (site) | Design | Sample | Interventions | Outcomes | Critique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Sparks Coburn & Hall, 2014 (USA) | Descriptive, comparative | 223 American nurses | Online survey to identify quality of work life (QWL), psychological empowerment (PE) and job satisfaction (JS) between four generations of nurses | Baby boomers have significantly more years of experience, perceptions of PE and JS than Generation X and Millennial nurses | Participant self-selection. Possible falsification of responses and identity. Exclusion of non-USA respondents. Online recruitment only. Generational responses not reflective of national population |

| Personal | Kovner, et al., 2006 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 1,538 American nurses working in metropolitan areas | Survey randomly mailed to examine factors that influence work satisfaction in metropolitan areas | Nurses who are Caucasian, self-perceived as healthy, working in nursing education, career oriented and have paid time off, are more satisfied | 54% of the variance in satisfaction is explained by: supervisor support, work-group cohesion, variety of work, autonomy, organizational constraint, promotional opportunities, work and family conflict, and distributive justice |

| Personal | Moore & Dienemann, 2014 (USA) | Mixed-method | 238 male nurses | Online survey to examine if JS differs between men who choose nursing as their first choice of career, as a convenience, or as a second career | No significant differences in JS found between entry paths. Second career nurses are more likely to work in specialty practice and aspire to work in advanced practice than first career nurses | Participant self-selection. Possible falsification of responses and identity. Participants with BScN or graduate degree 25% greater than national average. Participant average 10+ years of experience |

| Personal | Rochlen, Good & Carver 2009 (USA) | Descriptive | 174 American male nurses | Online questionnaire to examine gender role conflict, social support, gender-related work barriers, and work and life satisfaction of male nurses | Participants are overall well adjusted and content with their roles and lives. Career and life satisfaction is predicted by perceptions of gender-related work barriers, conflict between work and family, social support from significant others, confidence in job skills, and comfort in physical and emotional expression with other men | Participant self-selection. Possible falsification of responses and identity. Overwhelming response from Caucasian nurses (79%) and part-time employees (84%). SAJS and GRWB scales have not yet been evaluated. Causality of variables and direction is not determined |

| Personal | Wilson, et al., 2008 (Canada) | Descriptive, cross-sectional | 6,541 Ontario nurses | Mailed survey to Ontario nurses employed at acute-care hospitals to examine generational differences in JS | Baby boomers are significantly more satisfied with overall JS than Generation X and Y nurses as well as with pay and benefits, scheduling, and praise and recognition satisfaction (P-value <0.001) | Focused participant group limits generalizability |

| Cognitive | Aiken, et al., 2008 (USA) | Mixed-method | 10,184 Pennsylvanian nurses and 232,342 surgical patients from Pennsylvanian hospitals | Questionnaires mailed to nurses and patient outcome data collected from selected acute-care Pennsylvanian hospitals to measure care environment outcomes including nurse JS, burnout, intent to leave, reports of quality of care, mortality, and failure to rescue in patients | Hospitals with better care environments reported more positive JS, fewer concerns with quality of care, and significantly lower risks of death and failure to rescue | Data collected from 1999. Focused participant group limits generalizability. Failures to rescue values are estimated. Causality and direction is not determined |

| Cognitive | Bratt & Felzer, 2011 (USA) | Repeated measures | 468 newly licensed nurses employed in acute, Wisconsin hospitals | Nurses complete questionnaires at hospital at beginning of employment, 6 months, and 12 months after employment to examine their perceptions of their professional practice competence and work environment | JS is significantly lowest at 6 months and highest at 12 months. Job stress is lowest at 12 months. Organizational commitment is highest at baseline. Quality of nursing performance significantly increases with each measurement point | Study was non-experimental; therefore no control group was used to compare results. Focused participant group, and prominence of Caucasian females, limits generalizability. Completion at workplace, and in some cases, mandatory study participation enforced by workplace threatens internal validity. Use of same questionnaire at each measurement point may have created bias |

| Cognitive | Brown, et al., 2013 (USA) | Longitudinal, cohort | 47 certified nursing assistants (CNAs) employed at an Ohio long-term care facility | CNAs participate in advanced training program and surveyed with results compared to facility data to determine if program increases job satisfaction and in turn, impact turnover rates and clinical outcomes | Overall, JS improved slightly during study period. Turnover rates significantly decreased between pre-and post-intervention periods. Resident UTIs significantly decreased | Low response rate limit reliability. Inconsistent JS scores with national average. Short observation period (2 months) |

| Cognitive | Lerner, 2011 (USA) | Descriptive | 556 nursing assistants (NAs) from 12 Maryland nursing facilities | Existing data-set of survey results from sample used to explore factors found to influence JS | Years of experience and performance of restorative care is positively associated with JS. Self-esteem is negatively associated with JS | Parent study exclude NAs employed less than 6 months, limit generalizability. 30% refusal to participate rate also limits generalizability. Cross-sectional nature of parent study does not determine causality |

| Cognitive | Meyer, Raffle & Ware, 2014 (USA) | Longitudinal, ex post facto | 123 CNAs employed in American LTC settings | Survey CNAs at 6 months and 1 year post-training to identify retention and turnover issues | At 1 year post-training, 53.7% were working in LTC, 30.9% worked in LTC and left, and 15.4% never worked in LTC. 58.3% of CNAs working at 6 months but not at 1 year report pay as a problematic issue to worsen over time, and 50% report lack respect/recognition as an issue | Small sample size and high attrition rate (~66% drop-out before 1 year) limit generalizability. Young and rural sample also limit generalizability |

| Affective | Kalisch, Tschanen & Lee, 2011 (USA) | Descriptive | 3,135 nurses and 939 NAs from 10 Midwestern hospitals | Nurses were surveyed to explore the impact of missed nursing care on JS | Nurses who perceive less missed nursing care are more satisfied with their current position and occupation. Perceptions of staffing adequacy also significantly predict satisfaction | Sample limited to small hospitals. Measure of missed nursing care is based on perceptions, which is subjective to reporter bias |

| Affective | Mason, et al., 2014 (USA) | Non-experimental, descriptive, correlational | 26 experienced, surgical ICU trauma nurses from selected hospital | Nurses complete survey to examine the effect of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, moral distress, and level of nursing education on critical care nurses’ work engagement. In addition, nurses were also asked to describe sources of moral distress and self-care strategies for coping with stress | 58% scored average compassion fatigue while 42% scored low. 38% scored average secondary traumatic distress while 62% scored low. On average, moral distress situations were elevated and work engagement was low. As work engagement increased, compassion satisfaction significantly increased and burnout significantly decreased. Sources of moral distress reported were role conflict with management/rules, death and suffering, dealing with violence in the ICU, dealing with family, powerlessness, physical distress, and medical vs. nursing values. Sources of coping reported were caring, helping families, long-time interdependent relationships of colleagues, and satisfaction in trauma nursing | Purposive, small convenience sample limit generalizability (power sample of 59 not achieved) |

| Affective | Moneke & Umeh, 2014 (USA) | Non-experimental, quantitative | 204 critical care nurses employed in various ICUs across New York City healthcare organizations | Nurses complete online survey, by which they were invited to participate via email, to examine the relationship between critical-care nurses’ commitment to their organization and their overall JS | There is a significant correlation between organizational commitment and JS (r = 0.66, P = 0.00). No significant association is found between JS and demographic variables (gender, age, experience, education; F(5, 87) = 0.605, P = 0.69; ethnicity, specialty, shift; P > 0.05) | Sample limited to one American hospital. Small, purposive sample |

| Affective | Morrison & Korol, 2014 (Canada) | Grounded theory | 9 nurses working in the maritime district for a minimum of 5 years | Nurses participate in open-ended interviews to compare nurses’ caring expectations with their caregiving experiences | Concepts of monitoring and patient advocacy are key components of reported satisfaction or alienation. Discrepancies between management care expectations and nurses' perceptions of care provision are found. Level of nursing education is related to nurses' confidence in applying skills | Use of convenience sample. Under-representation of male nurse (1 male participant). Over-representation of experienced nurses (average experience of 15 years); nurses who have high compassion fatigue would leave job. Nurses with high JS are more likely to participate in such research. Retrospective nature of questions affects accuracy and bias |

| Social Relationships | Brewer, et al., 2006 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 25,471 female nurses working in urban USA | Secondary data from the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses 2000 (NSSRN), the InterStudy Competitive Edge Part III Regional Market Analysis 2001, and the Area Resource File 2002 was combined to produce sample to analyze factors that are related to female nurses working or not working, and working full or part time | Age of 55 and older, other family income, and prior work experience in health care are negatively related to working as a nurse. Wage, age, children, minority status, student status, employment status, and other income negatively influences full-time work. Previous health care work has a positive effect on whether married nurses work. Married nurses who are more dissatisfied are less likely to work full time. A greater number of market-level factors influence full/part-time work than working/not working behavior | Findings not compared to rural and male nurses. Data was collected from 2000–2002 sector of nurses. |

| Social Relationships | Ozkara, 2014 (USA) | Concept analysis | Articles selected from 1990 to present on the concept of nurse happiness | Articles were analyzed to examine and clarify the concept of nurse happiness | Attributes of nurses’ happiness are organized into three groups: personal factors, work characteristics, and work environment. Personal factors include age, gender, marital status, race, culture, educational level, and working experience | Articles from 1990 are included in analysis |

| Social Relationships | Tellez, 2012 (USA) | Longitudinal | 10,449–13,849 female nurses less than 65 years old working in California | Results from mailed survey at four points of time (1997, 2004, 2006, 2008) were analyzed to evaluate the effect of the nurse-to-patient ratios law on JS and to compare the results of nurse who are satisfied against those who are not | Overall JS increased significantly over time, suggesting law was associated with improved satisfaction. Satisfied nurses were more likely to have a balanced and financially secure life that included a partner, children living at home, higher hourly wages, and higher income from sources other than job. RNs working in direct patient care positions remained dissatisfied in larger proportions than nurses in other positions | Survey did not directly ask effect of law on JS. Large span of time also present other variables to influence increasing JS. Sample limited to female nurses |

Table 2.

Summary of literature on the health care system

| Sub-system | Authors, year (site) | Design | Sample | Interventions | Outcomes | Critique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attending physician | Manojlovich, 2005(USA) | Cross-sectional | 332 Michigan hospital nurses | Mailed surveys investigate direct and indirect relationships among the practice environment, nurse–doctor communication, and nursing JS | Practice environment and empowerment explain 20% of the variance in nurse–doctor communication. Combination of practice environment and nurse-doctor communication explain 61% of the variance in nursing JS. nurse–doctor communication is also a significant mediating variable in the relationship between practice environment, empowerment, and nursing JS | Cross-sectional nature of study provides data from only one instance |

| Attending physician | Vahey, et al., 2004 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 820 nurses and 621 patients from 20 urban hospitals across the USA | Nurses completed surveys and patients interviewed to examine the effect of the nurse work environment on nurse burnout, and their effects on patients' satisfaction with their nursing care | Patients were twice as likely to report high satisfaction and nurses’ report significantly lower burnout on units nurses characterized as having adequate staff, good administrative support for nursing care, and good relations between doctors and nurses | Causal relationship not determined. Data collected form 1991. Patient participants were diagnosed with AIDS and stayed at hospital a minimum of 3 days |

| Attending physician | Zangaro & Soeken, 2007 (USA) | Meta-analysis | 31 studies on nurses’ JS published from 1991 to 2003 | Examine the strength of the relationships between JS and autonomy, job stress, and nurse-doctor collaboration | JS was most strongly correlated with job stress (ES = −0.43), followed by nurse-doctor collaboration (ES = 0.37), and autonomy (ES = 0.30) | English, published literature only included in meta-analysis. Results generalized only to inpatient and outpatient settings |

| Other healthcare professionals | Castenada & Scanlan, 2014 (Canada) | Concept analysis | Literature published from 1980–2011 on the concept of JS in nursing | Examine the phenomenon of JS in nursing | JS is an affective reaction to a job that results from the incumbent’s comparison of actual outcomes with those that are desired, expected, and deserved. JS is comprised of autonomy, interpersonal relationships, and patient care | English literature only included in analysis |

| Other healthcare professionals | Dellasaga, et al., 2014 (USA) | Correlational | 842 American hospital nurses | Online survey to investigate relational aggression and the consequences among nurses | 14% had high aggressor scores, 16% high victim scores, and 11% high bystander scores. Scale has a weak correlation with JS and intent to leave (ITL). Aggressors, victims and bystanders are positively correlated to ITL and inversely related to JS | Instrument not verified with nurses. Sample limited to 1 hospital |

| Other healthcare professionals | Kalisch, Lee & Rochman, 2010 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 3,675 nurses from 5 American hospitals | Nurses complete Nursing Teamwork Survey to explore the influence of unit and staff characteristics, and teamwork on JS | JS with current position and with occupation are ranked higher when teamwork and perceived adequate staffing are ranked higher (P < 0.001). Both JS measures are influenced by type of unit (P < 0.05), but JS with occupation is influenced also by education, gender and job title | Data is based on self-report |

| Other healthcare professionals | Li, et al., 2014 (USA) | Longitudinal, descriptive | 251 pediatric nurses | Complete questionnaires at first and third month of residency program that determine if factors such as group cohesion and organizational commitment would be protective of negative nurse outcomes | Group cohesion is effective in decreasing compassion fatigue and burnout, and increasing compassion satisfaction. Organizational commitment promotes JS and compassion satisfaction | Limited sample group. Demographics and personality not assessed |

| Other healthcare professionals | Spence Laschinger, et al., 2014 (Canada) | Longitudinal, time-lagged | 545 Ontarian nurses from 49 hospitals | Surveys completed at baseline and 1 year to examine the effect of contextual and individual factors on nurses’ JS | Nurses shared perception of structural empowerment on their unit indirectly influences shared perception of unit effectiveness through perceived unit support. Perceived unit support has significant, direct, positive effect on unit effectiveness. Unit effectiveness is significantly related to JS at 1 year. Higher core self-evaluation has significant effect on JS through psychological empowerment | High rate of dropout before second phase |

| Multidisciplinary team | Al Sayah, et al., 2014 (Canada) | Enthography | 20 Albertan primary care nurses | Individual interviews conducted that investigate nurses’ roles and their perspectives on the factors that influence interdisciplinary teamwork within the primary care setting | Four themes of factors that facilitate or hinder teamwork are: organization/leadership, team relationships, process/support, and physical environment | Data is based on self-report. Perspectives of other disciplines is lacking in this study |

| Multidisciplinary team | Campbell, Fowles & Weber, 2004 (USA) | Descriptive | 192 public health nurses (PHNs) working in Illinois | Surveys examine the relationship between organizational structure and JS in PHNs | JS is positively related to work environments where supervisors and subordinates consult together concerning job tasks and decisions, and individuals are involved with peers in decision-making and task definition | Results may only be limited to PHNs. Volunteer participations and self-report |

| Multidisciplinary team | Djukic, 2014 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 1,141 early-career, American hospital RNs | Explore relationship between direct/indirect physical work environment factors and JS from results from an online survey | Direct physical work environment factors have an insignificant effect on JS. Indirect work environment factors (negative affectivity, variety, work-group cohesion, nurse-doctor relations, quantitative workload, organizational constraints, distributive justice, promotional opportunity, local/non-local job opportunities) have a significant, positive effect on JS (P < 0.05) | Specific sample population. Causality between physical and indirect factors unable to be determined |

| Multidisciplinary team | Spence Laschinger, 2004 (Canada) | Cross-sectional, exploratory | 285 nurses employed in Ontario teaching hospitals | Nurses complete survey on interactional justice, structural empowerment, perceived respect, work pressures, emotional exhaustion (EE) and work effectiveness | >50% of nurses feel managers do not show concern or treat them in a sensitive and truthful manner regarding decisions affecting their jobs. Consequences of feelings of respect are greater JS, quality of care, trust in management, and lower EE | Participant self-selection bias |

| Multidisciplinary team | Spence Laschinger & Finegan, 2005 (USA) | Non-experimental, predictive | 273 medical-surgical and critical care nurses employed in urban Ontario teaching hospitals | Mailed questionnaires evaluate the effects of employee empowerment on perceptions of organizational justice, respect, and trust in management | Structural empowerment has a direct effect on interactional justice, respect, and organizational trust. Empowerment has a cascading effect on organizational trust, JS, and organizational commitment | Scales may be out-dated |

| Inter-disciplinary and inter-organizational team | Amos, Hu & Herrick, 2005 (USA) | Group pre-test and post-test | 44 nurses, nurse assistants and nursing secretaries from 1 unit in a North Carolina hospital | Staff communication and JS were measured before and after a series of team building activities to examine their effectiveness | Team-building activities improved staff communication and JS | Responses vulnerable to social desirability. Incentive of educational credit may cause bias in self-reports. Results not longitudinal |

| Inter-disciplinary and inter-organizational team | Bormann & Abrahamson, 2014 (USA) | Descriptive, correlational | 115 acute care nurses | Unit staff completes surveys to explore the relationship between nurse managers’ leadership behaviors on the JS of nurses | Transformational and transactional leadership styles are positively related to nurse overall JS and satisfaction with opportunity for promotion. Passive-avoidant leadership style is negatively related to nurse satisfaction with work, promotion, supervision, and coworkers | Sample limited to one facility. Nurse manager perspective missing |

| Inter-disciplinary and inter-organizational team | Feather, Ebright & Bakas, 2014 (USA) | Qualitative, descriptive | 28 RNs from 2 Midwestern hospitals | Focus group interviews exploring RN's perceptions of nurse manager behaviors and their influence on JS | Two conceptual categories of RN perceptions of nurse manager behaviors were found: (1) manager behavior supportive of RNs (communication, respect and feeling cared for), (2) disconnect of work issues from the manager's role | Small sample size. Susceptible to “groupthink” and self-report. Geographical limitations |

| Inter-disciplinary and inter-organizational team | McDonald, et al., 2010 (USA) | Descriptive, correlational | 122 RNs employed at urban veteran affairs hospital | RNs complete online survey to measure their perception of structural empowerment and examine the relationship between this and RN participation in organizational structures | RNs perceived moderate structural empowerment and empowerment in opportunity, support and collaboration. No significant difference between RNs who attend council meetings and those who do not | Low response rate. Small number of participants who participate on councils. Sample collected from only 1 hospital. Did not examine unit-level empowerment |

| Inter-disciplinary and inter-organizational team | McGilton, et al., 2007 (Canada) | Descriptive, correlational | 222 NAs from 10 Ontario long term care (LTC) facilities | NAs complete survey to investigate the effects of perceived supervisory support provided by RNs on job stress and JS among NAs working in LTC | 33% of variance in JS is explained by supervisory support, stress, birthplace, and first language spoken of NAs. Greater supervisory support is associated with reduced job stress | Self-selection bias. Stressed employees may not rate their supervisor objectively |

Table 3.

Summary of literature on the workplace system

| Sub-system | Authors, year (site) | Design | Sample | Interventions | Outcomes | Critique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job position | Bellicoso, Ralph & Trudeau, 2014 (Canada) | Quantitative | 94 oncology nurses from 2 Toronto hospitals | Nurses participate in questionnaires to assess the impact of chronotype and sleep quality together with subjective measures of JS and stress | Greater tendency for evening or neither-type chronotypes and/or poor sleep quality to have greater levels of burnout than morning-chronotype and/or good sleep quality nurses | Unequal distribution of evening and morning chronotype participants. Missing other factors that may cause burnout |

| Job position | Djukic, et al., 2010 (USA) | Cross-sectional, predictive | 362 metropolitan hospital RNs | Survey to examine the effect of perceived physical work environment on JS | RNs rated their work environment well below other work groups in general. Race, negative affectivity, non-medical-surgical units, 12 h shifts, working overtime, autonomy, supervisor support, and work group cohesion are significantly related to JS | Low response rate. Responses from only one hospital. Causality is not determined |

| Job position | Kalisch & Lee, 2014 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 3,523 RNs and 1,012 NAs from 131 units | Unit staff is surveyed to examine the relationship between staffing and JS of RNs and NAs | Hours per patient day are a significant positive predictor for RN JS. Lower skill mix is marginally significant with higher JS in NAs. The more work experience reported in NAs, the lower their JS | Causality cannot be determined |

| Job position | Schiestel, 2007 (USA) | Descriptive, non-experimental | 329 Arizona adult health nurse practitioners (NPs) | Mailed surveys to determine JS among NPs | Mean overall satisfaction was 4.69 out of 6.0. JS scores did not significantly vary in employer type, gender, income, membership, or full/part-time employment | Focused sample group reduce generalizability. Self-selection bias |

| Job position | Tourangeau & Cranley, 2005 (Canada) | Descriptive | 8,456 RNs and RPNs working in acute care hospitals in Ontario | Mailed survey to explore the determinants of nurse intent to stay (ITS) in current organization of employment | 34% of variance in nurse ITS is explained by age, overall JS, and years of employment with current hospital. Significant determinants of ITS are: JS, personal characteristics of nurse, work group cohesion and collaboration, and organizational commitment. Burnout and manger ability and support are predictors of JS | Surveys conducted at approximately same time as SARS outbreak in Toronto. Results may only be limited to acute care hospitals. Multiple regression analyses does not account for the impact of correlations among predictors |

| Department | Braithwaite, 2008 (USA) | Concept analysis | Articles from 1982 to 2008 on the concept of burnout | Explore the causes and consequences of stress and burnout for nurses working in the NICU and strategies to prevent stress | High levels of psychological and physical stress experiences by NICU nurses can lead to burnout. Burnout results in emotional and mental exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased sense of personal accomplishment. Important components to preventing burnout are JS, emotional support, and self-care | Use of some out-dated articles |

| Department | Davis, et al., 2007 (USA) | Descriptive, comparative | 121 experienced critical care and medical-surgical nurses | Surveys explore the differences in JS between experienced critical care and medical-surgical nurses | No significant differences between critical-care and medical-surgical nurses in overall or sub-scores of determinants of JS | Two Magnet hospitals have clinical advancement processes in place such as self-scheduling. JS scale possibly invalid |

| Epp, 2012 (Canada) | Concept analysis | Articles published between 2007 and 2012 that examine burnout in critical care nursing | Explore how the chronic stressors that critical care nurses are exposed to contribute to the development of burnout, and strategies for burnout prevention | Nurse managers are crucial in preventing burnout by creating a supportive work environment. This includes being accessible to nurses, fostering collegial relationships among the different disciplines, and making a counselor or grief team available. Nurses supporting each other and implementing self-care strategies can also prevent burnout | N/A | |

| Department | Gardner, et al., 2007 (USA) | Descriptive, correlational | 199 nurses working on a dialysis unit | Nurses were surveyed to examine the relationship between nurses’ perceptions of dialysis work environments, ITL, and turnover | Nurses rated the work environment favorably, overall. Nurses ITL rated the work environment lower. Significant correlations are between perceptions of work environment, ITL, and turnover | Recruited from one organization. Social desirable responses from manager recruitment. Causality not determined |

| Department | Hinderer, et al., 2014 (USA) | Descriptive, cross-sectional | 128 trauma nurses employed in urban hospital | Survey to explore the relationships between personal/ environmental characteristics with burnout (BO), compassion fatigue (CF), and secondary traumatic stress (STS) | High BO and CF scores predict STS. BO, CF and STS are correlated with negative co-worker relationships, use of medication, and high number of hours worked per shift | Self-selection and report bias. Small number of sample exhibits STS |

| Organization | Bishop, et al., 2009 (USA) | Quantitative | 2,252 NAs employed in nursing homes across the USA | Survey to estimate the impact of nursing home work practices, specifically compensation and working conditions, on JS of NAs employed in nursing homes | JS is associated with wages, benefits and job demands. JS is greater when NAs feel respected and valued by their employers, had good relationships with supervisors, had enough time to complete their work, when their work was challenging, and when they were not subject to mandatory overtime | Focus on organizational level, not NAs' unit |

| Organization | Brewer, et al., 2009 (USA) | Descriptive, correlational | 1,348 RNs working across the USA | Surveys completed at baseline and 1 year later to determine how demographics, region, movement opportunities, and work setting variables affect RNs intent to quit (ITQ) or stay (ITS) and work behavior | At baseline, JS and organizational commitment are significant negative predictors of ITQ. At baseline, work motivation, work-family conflict, wages and benefits are significant positive predictors of ITS. Region, wages and benefits influence decision at 1 year. Organizational commitment and higher workload increase probability of working full time at 1 year | Could not measure nurses who left workforce before 1-year phase |

| Organization | Choi, Flynn & Aiken, 2012 (USA) | Correlational | 863 RNs employed in 282 New Jersey nursing homes | Examine relationships between aspects of the nursing practice environment and JS among RNs in nursing homes from survey data | RNs' participation in facility affairs, a supportive manager, resource adequacy, and ownership status were positively associated with RN's JS. RNs working in for-profit organizations are less satisfied | Sample limited to 1 state. Causality not determined. Self-reporting bias |

| Organization | Towsley, et al., 2014 (USA) | Mixed-method | 161 rural nursing homes (NHs) for survey and selected 23 NHs for qualitative interviews from western USA | Examine the impact of organizational and market characteristics of staffing hours and staffing mix through surveys, and explore the challenges and facilitators of recruiting and retaining qualified staff through selected interviews | Smaller nursing homes/government affiliated homes had more care hours per resident than larger/non-government homes. Challenges to recruitment/retention are number of staff, staff qualification, and training staff | No examination of trends over time. Findings specific to rural NHs |

| Organization | Osuji, et al., 2014 (Canada) | Descriptive, correlational | 193 RNs working in Calgary | Survey RNs to explore the turnover intentions and career orientations of RNs in Calgary | Age, education and length of service have a significant negative effect on turnover intention. Education and role ambiguity have a significant negative effect on career satisfaction but not on JS or OC. Growth opportunity and supervisor support have a significant positive effect of JS, career satisfaction and OC. External career opportunities and organizational commitment have no significant effect on turnover intention. Career satisfaction has significant negative effects on turnover intention | Single item constructs may have introduced construct bias. Focused sample group |

| External environment | Baernholdt & Mark, 2009 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 194 rural and urban nursing units among 97 U.S. hospitals | Using data collected from surveys of RNs on the unit and the annual American Hospital Association survey, differences in hospital characteristics, nursing unit characteristics, the nurse work environment, JS and turnover rates in rural and urban nursing units are determined | Rural hospitals have significantly lower technology complexity, proportion of RNs with baccalaureate degree or higher, and vacancy. Work complexity, availability of support services, safety climate, RN experience, expertise and commitment are similar between rural and urban hospitals. Location is not significantly associated with RN JS or turnover. Availability of support services, commitment to care and autonomy has a significant influence on JS. Work complexity and unit vacancy have a significant positive relationship with RN turnover. | Definition of rural may be too broad (population < 50,000) |

| External environment | Bratt, Baernholdt & Pruszynski, 2014 (USA) | Longitudinal, cohort | 382 urban and 86 rural newly licensed hospital nurses | Compare rural and urban residency program participants personal and job characteristics and perceptions of decision-making, JS, job stress, nursing performance at time of hire, 6 months and 12 months from results of surveys | At 12 months, rural nurses had significantly higher JS and job stress. At all time periods, rural nurses had significantly lower stress caused by physical work environment, and at 12 months less stress related to staffing | Dissimilar sample sizes. Type of education not measured to determine differences |

| External environment | Cole, Ouzts & Stepans, 2010 (USA) | Non-experimental, comparative | 88 PHNs employed as managers or staff in Wyoming | Survey conducted to determine JS among PHNs | Nurse managers and staff nurses report high JS. Managers are less satisfied with influence and interpersonal relationships | Low response rate among staff nurses |

| External environment | Molinari & Monserud, 2009 (USA) | Descriptive, correlational | 104 rural North-western America nurses | Explores relationships between rural nurse cultural self-efficacy and JS using an online survey | Self-efficacy is associated with rural lifestyle and JS. Nurses, who are older, experienced, and with urban backgrounds have more efficacies when caring for people of different ethnic or racial backgrounds, preferences, and health conditions. Higher cultural self-efficacy has greater intention to leave employment. Rural background nurses have more JS | Results may only be specific to geographical location |

| External environment | Roberge, 2009 (Canada) | Systematic review | Articles published between 1996 and 2006 that focus on rural nurse retention | Explore factors that influence rural nurse retention | Rural nurse retention is influenced by JS. Personal characteristics and experiences influence JS and duration of rural nurse practice | Literature on retention strategies differing between urban and rural settings is absent. Literature on the differences between types of nurses also absent |

Table 4.

Summary of literature on the compensation system

| Sub-system | Authors, year (site) | Design | Sample | Interventions | Outcomes | Critique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compensation agent | Ellenbecker & Byleckie, 2005 (USA) | Descriptive | 340 home healthcare nurses from 10 agencies in the USA | Explore the factors that contribute to the variability in home healthcare nurses’ JS from the results of a JS survey | The greatest amount of variability in JS is salary, benefits, stress, workload and organizational factors | Missing data from organizations on salary, benefits and workload. Reliance on self-report |

| Compensation agent | Qin, et al., 2014 (USA) | Longitudinal, correlational | 2,639 nursing homes HCWs in New England, USA | Determine the influence of specific workplace characteristics on filing of workers compensation claims among HCWs who report low back pain | 55.9% of participants reported low back pain within the past 3 months. 8.7% filed compensation claims. Most back pain caused by patient/material handling. Lower job strain, higher pain severity and physical demand increase probability of seeking compensation benefits. NAs are more likely to claim compensation. Other titles, higher levels of social support, education, BMI and higher level of schedule control decrease likelihood of filing a claim | Social desirability responses. 50% of claims made after first survey. Sample specific to nursing homes. Union membership increases likelihood to file a workers compensation claim, but none of the selected homes were unionized. |

| Compensation agent | Spetz, 2008 (USA) | Longitudinal | 5,066 RNs employed in California hospitals | Examines whether nurses employed in California hospitals have perceived improvements in working conditions since the passing of the minimum staffing levels legislation in 1999. This is measured by 2 surveys completed by nurses at 2004 and 2006 in conjunction with regional survey data | Overall nurse satisfaction improved from 2004 to 2006, particularly with staffing adequacy, time for patient education, benefits, and clerical support | Survey does not specifically ask if law has improved their JS. Other factors may have caused improvement in satisfaction. Staffing is compared to regional average, not organizational |

| Compensation agent | Unruh, 2005 (USA) | Policy brief | Articles from 1980 to 2004 on the factors that affect the RN shortage | Examine conditions that make bedside nursing unattractive compared to other professions and other nursing occupations | Factors that prevent and drive individuals away from bedside nursing include unstable demand, difficult working conditions, and low wages | Focus on RN shortage in Florida. Non-experimental, causality cannot be determined |

| Compensation agent | Wieck, Dols & Northam, 2009 (USA) | Non-experimental, correlational | 1,599 RNs employed in 22 South-western U.S. hospitals | Launch of the Nurse Incentive Project to determine satisfaction with current employment incentives and potential managerial actions that might decrease or delay turnover by RNs through surveys | The top three incentives for Millennial RNs are: overtime pay, paid time off, and premium pay. The top three incentives for Generation X RNs are: work environment, overtime pay, and premium pay. The top three incentives for Baby Boomer RNs are: paid time off, pension, and retirement benefits | None of the hospitals were involved with collective bargaining contracts. Low response rate. Sample has rich ethnic mix |

| Workers’ compensation board/insurer caseworker | Porter, et al., 2010 (USA) | Quasi-experimental | 1,719–1,856 RNs employed at Magnet, urban teaching hospital in North-eastern U.S. | The nursing labor management partnership intervention's effect on nurse turnover and satisfaction is examined before (2005) and after (2008) it's implementation. The intervention had nursing leaders (bargaining and non-bargaining) work collaboratively to improve patient care and outcomes | A significant decrease in nurse turnover and significant increase in nurse satisfaction resulted after the intervention | Sample groups were not kept the same between the two periods |

| Workers’ compensation board/insurer caseworker | Seago, et al., 2011 (USA) | Descriptive, correlational | 35,724–33,549 RNs working in the USA | Examine whether unionization is associated with the JS among RNs in the USA using nationally representative surveys of RNs (2004 and 2008) | In 2004 and 2008, union representation was negatively associated with JS but has improved slightly | Union nurses may be more vocal and less fearful about voicing concerns |

| Workers’ compensation board/insurer caseworker | Swan & Harrington, 2007 (USA) | Correlational | 1,155 nursing facilities (NFs) in California | Examine the effects of unionization on quality of NFs | Unionized NFs show more complaints than nonunionized NFs. Nonunionized NFs had more serious violations, particularly when the proportion of unionized NFs in the county was higher | Unionization characteristics may vary from this state |

| Medical evaluation office | Castle, et al., 2009 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 3 survey pools from 2004 on occupational safety and regional demographics | Examine the association between workplace injuries and organizational factors, caregiver staffing levels, and quality | For-profit facilities and facilities with high NA staff levels are less likely to report high injury rates. Facilities with high RN staff levels and are of lower quality are more likely to report high injury rates | Causality cannot be determined. Injuries may be underreported. Findings may have limited practical significance |

| Medical evaluation office | Martin, 2011 (USA) | Cross-sectional | 735 nurses working in Maine | A questionnaire explores factors affecting nurses’ ability and willingness to work during the 2009 pandemic flu | 90.1% reported they would work. Willingness decreased primarily when PPE dwindled, the nurse or family member perceived to be at risk, and when vaccine and antiviral medication was not provided to the nurse and/or their family. Ability decreased primarily when the nurse was sick, a loved one needed care at home, or when transportation problems existed | Minimal racial, ethnic and gender diversity. Self-selection bias. Measured intentions, not actual behavior |

| Medical evaluation office | Neal-Boylan, 2008 (USA) | Qualitative | 14 RNs with physical disability working in North-eastern USA | RNs with physical disability and nurse employers are interviewed to explore their experiences | RNs with physical disability are leaving the workplace. These nurses often hide their disabilities because they fear being rejected for employment and being stigmatized by colleagues. Employers are not typically making accommodations to permit these nurses to work safely and effectively | Sample is not diverse in ethnicity and gender. In nature to qualitative studies, the findings cannot be generalized |

Personal system

Physical

Five articles were analyzed to explore the diverse physical factors that affect work ability. Using surveys collected from moderate to large sample sizes (174–6,541), each study described the relationship between job satisfaction and nurses’ age, sex, and ethnicity. One study also described the relationship between age and perceptions of personal empowerment in the workplace, and outcomes shown to be influential in nurses’ job satisfaction and work ability.10 The age-related articles showed that participants of the Baby Boomer generation (individuals born during the demographic post-World War II period approximately between the years 1946–1964) had greater job satisfaction and personal empowerment than other generations.10−13 Male participants were found to be satisfied with their career, irrespective of their method of entry, and Caucasian nurses reported greater job satisfaction than non-Caucasian participants.14,15 A primary bias within three of the studies involved sample misrepresentation of the American nursing population.10,14,16 Another risk of bias was the use of two unevaluated scales in the interpretations of results.14 Common with the use of self-selection surveys, the risk of self-selection bias and response bias is prevalent in all five of these studies.

Cognitive

Five articles explored the relationship of QWL with length of education and years of experience. Using cross-sectional designs, job satisfaction and work ability improved in nurses with years of experience and highly rated work environments.17,18 These results are supported in a longitudinal study where newly licensed nurses reported greatest levels of job satisfaction, retention and work ability, and lowest levels of stress at one year after employment.19 Interestingly, both nurses and certified nursing assistants presented a drop of job satisfaction at six months after their employment start date.19,20 These two longitudinal studies, however, present response bias with the use of the same survey at each test point, and 66% attrition before the 1 year test point. 19,20 Job satisfaction, retention, and work ability scores were also reported greater after a continuing education seminar for a small sample (n = 47) of certified nursing assistants.21

Affective

The studies selected were useful in exploring the relationship of the concepts that compose QWL. As supported by older evidence, job satisfaction and retention are shown to have a significant correlation (P < 0.001).22 In addition, as reported levels of work engagement increased, compassion satisfaction significantly increased while burnout decreased.23 Through surveys and interviews, a plethora of concepts relating to job satisfaction and stress were found. These concepts include: missing nursing care, perceptions of staff, monitoring, patient advocacy, role conflict with management, patient death and suffering, violence, dealing with patients’ families, feelings of powerlessness, physical distress, and moral conflict.23–25 Sources of coping with stress were also explored including: caring, helping families, relationships with colleagues, and job satisfaction.23 All of these studies, however, are at a risk of bias using small, convenient samples that only target rural hospitals or specific units, or nurses who have been working in the same position for over five years.

Social relationships

The articles selected for this theme investigate the social relationships a nurse has outside of the workplace, and how they correlate to their QWL. A concept analysis on nurse happiness was completed and stated that nurses’ happiness can be attributed to a number of personal factors.26 These personal factors include age, gender, marital status, race, culture, educational level, and work experience.26 Using data collected from the National Sample Survey of nurses in 2000, female nurses working in urban USA were less likely to still be employed if they were 55 and older, had other family income, and had prior work experience.27 Married nurses with previous health care work experience, however, are more likely to be still working.27 Factors related to being less likely to be working full-time included: an age of 55 and older, marriage, children, a greater wage, other family income, minority status, and being a student.27 In a longitudinal study, female nurses who are younger than 65 and working in California were surveyed to discover which personal factors affected their job satisfaction and they included: a life partner, children living at home, and higher wages.28

Healthcare system

Other healthcare professionals

The articles selected for this category focused on collegial nurse relations. There was evidence supporting the relationship between positive interpersonal relationships and nurse job satisfaction.29,30 More recent evidence supported these findings in longitudinal studies where group cohesion was shown to decrease stress and increase job satisfaction, and perceived unit effectiveness (as achieved through perceived unit support) has a significant correlation with job satisfaction over time. 31,32 A unique study examining the consequences of relational aggression among nurses found a positive correlation between nurses who have aggressor, victim or bystander attributes with those who intend to leave the workplace; an inverse correlation is also found with job satisfaction.33 Stress was exacerbated with negative collegial relationships, medication use by nurses, and working overtime.34 Stress was reported to be relieved by manager accessibility to nurses, intra-disciplinary relationships, and counselor accessibility in a concept analysis on nurse burnout in critical care units.35

Attending physician

A meta-analysis on nurses’ job satisfaction using literature from 1991 to 2003 was used for its findings on nurse-doctor collaboration; nurse job satisfaction was strongly correlated with nurse-doctor collaboration (effect size = 0.37).36 In addition, a cross-sectional study showed that practice environment and empowerment explain 20% of the variance in nurse–doctor communication.37 The combination of practice environment and nurse–doctor communication explained 61% of the variance in nurse job satisfaction.37 In another cross-sectional study, patients were twice as likely to report high satisfaction and nurses’ low burnout on units with adequate staffing, good administrative support, and good nurse–doctor relations.38 The nature of cross-sectional studies, however, cannot predict repeated results and therefore reduce the reliability of these studies.

Multidisciplinary team

Similarly to the “Other healthcare professionals” category, literature exists on the relationship between nurses and administrative team members. From interviews with 20 primary care nurses, positive organizational/leadership support and team relations were described as valuable to effective teamwork.39 Job satisfaction was found to have a significant correlation with work-group cohesion, organizational constraints, distributive justice, shared decision-making, feelings of respect from managers, and structural empowerment.40−43

Interdisciplinary and inter-organizational team

Nurses’ perceptions of supervisor support have a significant effect on their feelings of job satisfaction (33% variance in job satisfaction).44 In an online survey of nurses (n = 122) employed at an urban hospital, nurses perceived only moderate structural empowerment and support.45 Characteristics that improve managerial behavior (and thus job satisfaction) include communication, respect, caring, and transformational or transactional leadership styles.46,47 Team-building activities were also shown to improve interdisciplinary communication and job satisfaction.48 Each of these studies is at risk for bias due to small sample size (ranging from 28 to 222). However, when considered together, there seems to be correlation between organizational support and nurse job satisfaction.

Workplace system

Job position

Work aspects including longer lengths of shifts, working overtime, and increasing workload were significantly related to poorer job satisfaction for nurses.49,50 These findings, however, were derived from cross-sectional studies, reducing the reliability of these results. A survey involving nurse practitioners (NPs) showed no variance in satisfaction between full-time and part-time employees.51 Another unique study found that nurses with an evening or neither-type chronotypes (time of day for work is completed most efficiently) have a greater tendency for burnout.52 Number of years with their current organization was also significantly correlated with retention.53 This study may be at risk for bias as the data collection period occurred during the SARS outbreak in Toronto.

Department

The articles selected for this section represent a variety of health care departments and their nurses’ relationships with stress, retention, and job satisfaction. Departments with high reports of stress include critical care units, trauma units, and the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.34,35,54 Negative work environment perceptions were significantly correlated with intent to leave with a 199 sample from a single dialysis unit.55 Lastly, no significant difference in job satisfaction was found between nurses employed in critical care or medical-surgical units.56

Organization

Significant factors related to job satisfaction for CNAs employed in nursing homes included wage, benefits, and job demands.57 For nurses, job satisfaction was positively associated with participation in facility affairs and resource adequacy, and negatively correlated with employment in for-profit organizations.58 In a longitudinal study, wages and benefits were positive predictors of nursing home employed nurses’ retention at baseline and 1 year later.59 The reports of nurses who quit before 1 year could not be surveyed; therefore, there is potential bias in the results of the second phase. For a sample of RNs in Calgary, organizational commitment had no significance on their decision to leave or stay in their current position.60 Through interviews with selected rural American nursing home owners, number of staff, staff qualifications, and staff training were revealed to be challenges in nurse retention.61 These studies all presented bias from their narrow sample selections.

External environment

When comparing nurses working in rural and urban work environments, rural nurses reported significantly greater job satisfaction.62−64 A systematic review focusing on rural nurse RT (literature from 1996 to 2006) found that rural retention is influenced by job satisfaction.65 However, a cross-sectional study of 194 rural and urban nursing units found that location was not significantly associated with RN job satisfaction or retention.66 Nurses of urban backgrounds working in rural areas were also less likely to stay in their position.64 A longitudinal study reported that newly licensed rural nurses had more overall stress excluding stress related to staffing, and less stress related to the physical work environment than nurses working in urban settings.62

Compensation system

Compensation agent

Factors found to have the greatest influence on job satisfaction include: salary, benefits, stress, workload, adequate staffing, time to educate patients, and clerical support.67,68 Factors that significantly decreased bedside nurse retention include the position’s unstable demand, its hard working conditions, and low wages.69 A large survey of 1,599 RNs employed in southwestern US hospitals tabulated the top incentives for staying in their current position by generation.70 The results include: overtime, off time and premium pay for Millennial RNs (born in the 1980s to around 2000); work environment, overtime and premium pay for Generation X RNs (born in the 1960s to mid 1970s); and off time pay, pension, and retirement plans for Baby Boomer RNs.70 Another study explored the factors related to compensation claim for work-related lower back pain.71 Of 2,639 nursing home workers, 55.9% reported lower back pain within the past three months, and only 8.7% filed compensation claims.71 Certified nursing assistants were the most likely to file claims while other positions, workers with higher levels of support, education, BMI and schedule control were less likely.71 This study was at risk of social desirability responses and bias due to the fact that 50% of the claims were filed after the first survey.71 This sample also only contained non-unionized NHs, which are less likely to file compensation claims.71

Workers’ compensation board/insurer caseworker

A survey examining the relationship between unionization and nurses’ job satisfaction across the USA (n = 35, 724 and 33,549) found that union representation was negatively associated with job satisfaction in both 2004 and 2008 although with a slight improvement.72 In another longitudinal study with a smaller sample (n = 1,719 and 1,856), nurses’ turnover decreased and job satisfaction increased after the implementation of the nursing labor management partnership intervention that had bargaining and non-bargaining parties work collaboratively to improve patient care and outcomes.73 In California, unionized nursing facilities were shown to have claimed more violations than those that are non-unionized.74 Apart from the national survey, the results of these studies may be difficult to disseminate for the varying unionization laws across each state, province and territory.

Medical evaluation office

A survey that explored 750 nurses’ willingness and ability to work during the 2009 pandemic flu in Maine reported that 90.1% were willing to work but dwindled with decreasing personal protective equipment availability, perception of self or family member getting sick, and vaccination or antiviral medication not being provided to the nurse or their family.75 work ability decreased when the nurse or their family member became sick, and when transportation problems arose.75 Another study interviewing nurses with physical disability (n = 14) found that they often plan to leave the profession, do not typically receive accommodation from their employers, and often hide their disability for fear of stigmatization.76 Nurses working in for-profit facilities, with clinically competent certified nurses’ assistant adequacy are less likely to report injury, while nurses employed in facilities that are perceived as low quality, and have high nurse adequacy are more likely to report injury.77 Samples of these studies lack in gender and racial diversity, which create bias in the results.75,76

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to review literature from 2004 to 2014 that examined the relationship between internal and external variables on the QWL life of nurses in the United States and Canada. Recent graduate nurses consistently experienced low QWL.17−19 Recent graduates have decreased job satisfaction and work ability only one year. To improve their comfort in their work environment, they are required to learn quickly. Their inexperience, lack of continuing education, and poor relationships with their team were predictors of low QWL. Part of this is inevitable as they enter the workforce and increase their clinical nursing competencies.

However, strategies can be used to mitigate low QWL. One strategy would be through the implementation and evaluation of continuing education programs within the workplace. Continuing education increases job satisfaction and work ability and therefore should be encouraged with both new and experienced nurses to create opportunities for collegial relationship building. It is important that continuing education and evaluation programs continue beyond the first year of work and address not only decreased job satisfaction after one year, but also ensure professional practice and patient safety. Focusing on new nursing graduates is important to the quality of work life for all nurses as their technical skills are necessary for the function of future health care practices, and surplus in number are essential to their growing demand.

Collegial relationships with nurses, other health care professionals and management were frequently a source of improvement toward quality of work life in all areas of the literature review. Positive collegial relationships empower nurses, which in turn improves factors related to quality of work life.29,40,42,43 Respect and empowerment of nurses is found to align closely with increased job satisfaction. Thus, it is important to have an integrated unit with nurses who have positive attitudes to foster a healthy working environment. Negative or aggressive attitudes ought to be discouraged and any nurse displaying such attributes should receive help. Collegial relationships can be improved through formal team building exercises and informal events. Health care professionals’ collaboration with administrative colleagues while hiring and developing programs and services for employees in the organization can also encourage positive relationships with new employees and create programs and services that produce more effective outcomes. Programs that target healthy behaviors to relieve stress would be significant tool in improving nurses’ QWL, particularly for nurses working in critical care or fast-paced units. Literature has also shown that job satisfaction and longer retention times can be increased with shorter shifts and less evening shifts during a week, which subsequently leads to a reduction of burnout in these nurses.43,50

Lastly, reasonable financial compensation is shown to have a significant correlation with nurses’ quality of work life. Financial compensation that is commensurate to nurses work experience, loan forgiveness programs after graduation from nursing school, recognition of nurses’ value (other than salary) in the workplace, increases job satisfaction and retention and improves work ability in the case of a work-related injury.72,78−80 Unstable demands and work related injury such as back-pain should be avoided (assuming the work-injury is unintentional) to increase job satisfaction and retention as well as reduce compensation claims. Financial compensation can be improved with lobbying from the profession, as well creating a more supportive work environment to encourage nurses to claim compensation for work-related injuries from the workplace colleagues and nurse’s union. More frequent and current research on nursing unions and compensation claims are needed to assess their influence on nurse’s quality of work life.

Overall, it was found that the factors that influence the quality of work life extend beyond a nurses’ salary or workload. They value career and education satisfaction, as well as an environment that supports their own well-being. Therefore, the health care system must create a healthy environment that benefits nurses and patients through improved methods by the union to monitor the health and well-being of nurses, as well as encourage healthy behavior.

Limitations

Literature was limited to English language articles published in Canada and the United States. These inclusion criteria make this review only applicable to nursing in these two countries. Literature on nursing educators was also excluded. The search was limited to themes from the Work Disability Prevention Framework, which excludes specific variables relevant to the profession that could be significant in predicting their disability (e.g. patient interactions and outcomes).

Conclusion

As the health care systems in Canada and the United States evolve, the nursing profession must adapt in turn. Key areas for improvement to nurses’ quality of work life include improved treatment of new nursing graduates, continuing education opportunities, promotion of positive collegial relationships, providing stress-reduction programs, and increased financial compensation. These can be achieved within the workplace through positive interactions with colleagues and nurses’ involvement in organizational decisions and programming, and in the public by lobbying for improved compensation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Robinson S, Griffiths P. Nursing education and regulation: international profiles and perspectives. London: University of Southampton; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shamian J, El-Jardali F. Healthy workplaces for health workers in Canada: knowledge transfer and uptake in policy and practice. HealthcarePapers. 2007;7(sp):6–25. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2007.18668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vagharseyyedin SA, Vanaki Z, Mohammadi E. The nature nursing quality of work life: an integrative review of literature. Western J Nurs Res. 2010;33(6):786–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks BA, Storfjell J, Omoike O, Ohlson S, Stemler I, Shaver J, et al. . Assessing the quality of nursing work life. Nurs Admin Q. 2007;31(2):152–7. 10.1097/01.NAQ.0000264864.94958.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowrouzi B, Lightfoot N, Carter L, Larivière M, Rukholm E, Schinke R, et al. . Work ability and work-related stress: a cross-sectional study of obstetrical nurses in urban northeastern Ontario. Work. 2015;52(1):115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royuela V, López-Tamayo J, Suriñach J. Results of a quality of work life index in Spain. A comparison of survey results and aggregate social indicators. Soc Indic Res. 2009;90(2):225–41. 10.1007/s11205-008-9254-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks BA, Anderson MA. Defining quality of nursing work life. Nurs Econ. 2005;23(6):319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phy Ther. 2009;89(9):873–80. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loisel P, Durand M-J, Berthelette D, Vézina N, Baril R, Gagnon D, et al. . Disability prevention. Dis Manag Health Out. 2001;9(7):351–60. doi: 10.2165/00115677-200109070-00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coburn AS, Hall SJ. Generational differences in nurses’ characteristics, job satisfaction, quality of work life, and psychological empowerment. J Hosp Admin. 2014;3(5):124–34. doi: 10.5430/jha.v3n5p124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson B. Job satisfaction among a multigenerational nursing workforce. J Nurs Manage. 2008;16(6):716–23. 10.1111/jnm.2008.16.issue-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Canada. Generations in Canada. Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 2015. [cited 2016 June 25]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-311-x/98-311-x2011003_2-eng.cfm

- 13.Werner CA. The older population: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochlen AB, Good GE, Carver TA. Predictors of gender-related barriers, work, and life satisfaction among men in nursing. Psy of Men & Masc. 2009;10(1):44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovner C. Factors associated with work satisfaction of registered nurses. J Nurs Scholarship. 2006;38(1):71–9. 10.1111/jnu.2006.38.issue-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore GA, Dienemann JA. Job satisfaction and career development of men in nursing. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2014;4(3):86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Admin. 2008;38(5):223–9. May. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerner NDNP, Resnick B, Galik E, Flynn L. Job satisfaction of nursing assistants. J Nurs Admin. 2011;41(11):473–8. Nov. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182346e7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bratt MM, Felzer HM. Perceptions of professional practice and work environment of new graduates in a nurse residency program. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2011;42(12):559–68. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20110516-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer D, Raffle H, Ware LJ. The first year: employment patterns and job perceptions of nursing assistants in a rural setting. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(6):769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown M, Redfern RE, Bressler K, Swicegood TM, Molnar M. Effects of an advanced nursing job satisfaction, turnover rate, assistant education program on and clinical outcomes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(10):34–43. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130612-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moneke NI, Umeh OJ. How organizational commitment of critical care nurses influence their overall job satisfaction. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2014;4(1):148–61. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason VM, Leslie GMSN, Clark KBSN, Lyons PMS, Walke EMSN, Butler CBSN, et al. . Compassion fatigue, moral distress, and work engagement in surgical intensive care unit trauma nurses: A pilot study. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2014;33(4):215–25. Jul/Aug. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalisch B, Tschanen D, Lee H, Salsgiver MW. Does missed nursing care predict job satisfaction? J Healthc Manag. 2011;56(2):117–31; discussion 32-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison KB, Korol SA. Nurses’ perceived and actual caregiving roles: identifying factors that can contribute to job satisfaction. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(23–24):3468–77. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozkara San E. Concept analysis of nurses’ happiness. Nurs Forum. 2014. n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewer CS, Kovner CT, Wu Y-W, Greene W, Liu Y, Reimers CW. Factors influencing female registered nurses' work behavior. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(3p1):860–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tellez M. Work satisfaction among california registered nurses: A longitudinal comparative analysis. Nurs Econ. 2012;30(2):73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castaneda GA, Scanlan JM. Job satisfaction in nursing: A concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2014;49(2):130–8. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalisch BJ, Lee H, Rochman M. Nursing staff teamwork and job satisfaction. . J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(8):938–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li A, Early SF, Mahrer NE, Klaristenfeld JL, Gold JI. Group cohesion and organizational commitment: protective factors for nurse residents’ job satisfaction, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout. J Prof Nurs. 2014;30(1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laschinger HKS, Nosko A, Wilk P, Finegan J. Effects of unit empowerment and perceived support for professional nursing practice on unit effectiveness and individual nurse well-being: a time-lagged study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(12):1615–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellasega C, Volpe RL, Edmonson C, Hopkins M. An exploration of relational aggression in the nursing workplace. J Nurs Admin. 2014;44(4):212–8. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinderer KA, VonRueden KT, Friedmann E, McQuillan KA, Gilmore R, Kramer B, et al. . Burnout, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress in trauma nurses. J Trauma Nurs. 2014;21(4):160–9. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epp K. Burnout in critical care nurses: a literature review. Dynamics. 2012;23(4):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zangaro GA. A meta-analysis of studies of nurses' job satisfaction. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):445–58. 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-240X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manojlovich M. Linking the practice environment to nurses’ job satisfaction through nurse-physician communication. J Nurs Scholarship. 2005;37(4):367–73. 10.1111/jnu.2005.37.issue-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke SP, Vargas D. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2004;42(2):II57–II66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al Sayah F, Szafran O, Robertson S, Bell NR, Williams B. Nursing perspectives on factors influencing interdisciplinary teamwork in the Canadian primary care setting. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(19–20):2968–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell SL. Organizational structure and job satisfaction in public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2004;21(6):564–71. 10.1111/phn.2004.21.issue-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Djukic M, Kovner CT, Brewer CS, Fatehi F, Greene WH. Exploring direct and indirect influences of physical work environment on job satisfaction for early-career registered nurses employed in hospitals. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37(4):312–325. doi: 10.1002/nur.21606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spence Laschinger HK. hospital nurses’ perceptions of respect and organizational justice. J Nurs Admin. 2004;34(7):354–64. 10.1097/00005110-200407000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spence Laschinger HK, Finegan J. Using empowerment to build trust and respect in the workplace: a strategy for addressing the nursing shortage. Nurs Econ. 2005;23(1):6–13, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGilton KS, Hall LM, Wodchis WP, Petroz U. Supervisory support, job stress, and job satisfaction among long-term care nursing staff. J Nurs Admin. 2007;37(7/8):366–72. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000285115.60689.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]