Abstract

This paper provides a brief summary and commentary on the growing literature and current developments related to the genetic underpinnings of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We first briefly provide an overview of the behavioral genetic literature on PTSD, followed by a short synopsis of the substantial candidate gene literature with a focus on genes that have been meta-analyzed. We then discuss the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that have been conducted, followed by an introduction to other molecular platforms used in PTSD genomic studies, such as epigenetic and expression approaches. We close with a discussion of developments in the field that include the creation of the PTSD workgroup of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, statistical advances that can be applied to GWAS data to answer questions of heritability and genetic overlap across phenotypes, and bioinformatics techniques such as gene pathway analyses which will further advance our understanding of the etiology of PTSD.

Introduction and History of Genetics of PTSD

The classification of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within the category of “trauma- and stressor-related disorders” of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5 [1]) highlights a continued, unique challenge for genetic and epigenetic investigations of PTSD, given the diagnostic requirement of exposure to a traumatic event [2], and thus, both cases and controls in genomic studies must be exposed to a traumatic event. While the prevalence of trauma exposure is high (50-60% of the US adult population will be exposed to at least one traumatic event in their lifetime), the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is comparatively low (ranging from 7-30% depending on population and trauma type [3]), pointing to the importance of individual differences in response to trauma. While numerous psychosocial factors are related to risk for PTSD [4], evidence from family, twin, and molecular studies suggest genetic differences are also an important etiologic source of variability in risk [5, 6]. This review opens with a brief summary of behavioral genetic studies of PTSD, which provide the basis for molecular studies aimed at identification of specific genetic variation, followed by an overview of the growing molecular genomic literature, concluding with a discussion of new developments in the field.

Early work provided evidence for familial influences on PTSD. Over 100 studies of parental and offspring PTSD in trauma-exposed samples have been conducted (see recent meta-analysis [7] and review [8]). Although this line of research suggests that PTSD ‘runs in families,’ these parent-offspring designs are complicated by shared genetic and environmental risk. A second behavioral genetic design, twin studies, affords the ability to disentangle shared environmental influences from heritable influences. Twin studies (see review [9]) have demonstrated that PTSD is moderately heritable (even after controlling for genetic influences on exposure to trauma itself [5]; i.e., gene-environment correlation, rGE [10]) and that genetic influences on PTSD are shared with those for other phenotypes (e.g., complete overlap with major depression [11]).Sex differences in heritability have not been formally tested, as samples including both males and females (e.g., [12]) have not been sufficiently powered. However, examination of the pattern of findings across studies suggests that sex effects may be present (i.e., estimates of heritability differ by population, ranging from approximately 30% in male Veterans [5] to 72% in civilian women [6]). Thus, the heritability for PTSD may be nearly two to three times higher for females than males; however, a well-powered twin study of both sexes would need to be conducted to determine if there is a significant difference.

While twin studies have demonstrated latent genetic influences for PTSD, molecular genetic studies aim to identify specific genetic variation that may account for increased risk (see [13**] for a review and primer on genetic studies). Although a new endeavor, over 100 studies searching for genetic markers of PTSD have been published since 1991.Despite increased growth of this literature, the molecular architecture of PTSD remains largely uncharted. Following, we provide an overview of molecular genetic risk for PTSD identified to date, including candidate gene and genome-wide association studies (GWAS [14, 15**]. Other genomic platforms (i.e., gene expression and methylation) will be briefly discussed, with recent reviews highlighted.

Molecular Genetics

The majority of the extant molecular genetic studies have utilized a candidate gene design, examining either main effects or interactions with environmental variables (e.g., trauma load) in gene by environment (G×E) designs. More recently, GWAS studies have been conducted, with eight published to date. Another exciting direction in the field of molecular genetics of PTSD is that of the formation of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium PTSD workgroup [15**], discussed in the future directions section.

Candidate Gene Studies

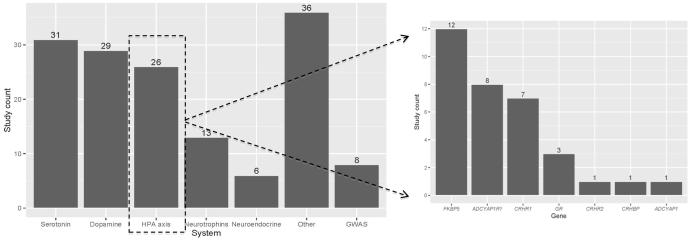

In the candidate gene approach, selection of the gene(s) is informed by existing biological evidence, with candidate approaches targeting polymorphisms within and around the gene region of interest. The most commonly studied genetic variation in molecular studies of PTSD is single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), in which a location in the genome has variation in a single nucleotide sequence. A wide variety of polymorphisms within genes selected from different candidate systems have been studied in relation to PTSD (see Figure 1a); to date there have been polymorphisms within 52 genes studied in relation to PTSD. This literature, similar to that of other psychiatric phenotypes, has had a number of independent replications as well as published studies that have failed to replicate initial findings. As an exhaustive discussion of the vast PTSD candidate gene literature is beyond the scope of this review, readers are directed to comprehensive reviews for further details [14-17*] and we focus our presentation of the candidate gene literature on those polymorphisms that have been meta-analyzed, and briefly highlight a few markers in a system that has gained increased interest.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Molecular Genetic Studies of PTSD conducted to date. Figure 1b. Specific candidate genes studied within the HPA axis. System = neurotransmitter system of interest; Gene = HPA axis related gene; GWAS = genome-wide association study.

Note: These counts are not exhaustive of all PTSD association studies and only include those that primarily examined an association and had a control comparison group. Counts for this figure were derived from review articles (Almli et al., 2013 and Voisey et al., 2014) as well as an updated review of the literature by author ML. COMT has been categorized within the dopaminergic system.

Of those meta-analyzed, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR; [18, 19]) represents one of the most highly studied polymorphisms. Both meta-analyses (including 13 and 12 studies, respectively, of which five in each were significant) found no overall association with PTSD, although suggested the importance of potential G×E with level of trauma exposure. A meta-analysis of the Val88Met SNP in the brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) gene [20] (including six studies, two of which were significant), found an association only when restricting to trauma-exposed controls. A more recent meta-analysis [21] (including nine studies, four significant) found only trend-level support for an association. A meta-analysis of dopaminergic system genes [22] resulted in significant overall associations for DRD2 (rs1800497; five of six studies significant) and SLC6A3 (3’ UTR variable tandem repeat polymorphism; five of five significant), but no effect for COMT Val158Met, likely due to different directions of effect across the five included studies). These meta-analyses represent one way of summarizing existing evidence, highlight important factors such as differing directions of effect and utilizing a proper trauma-exposed control group, and represent a useful direction for continued efforts as the number of studies for additional polymorphisms increase.

Specifically, there are numerous genes and gene systems that have yet to be meta-analyzed (i.e., five of 52 genes studied in candidate approaches have been meta-analyzed to date) yet appear to be promising. For example, genes involved in regulation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis system serve as useful exemplars (Figure 1b), given the HPA-axis’ biological plausibility in the context of systems involved in PTSD risk (i.e., stress response; see [23*]). Two such candidate genes include the FK-506 binding protein (FKBP5, modulates the glucocorticoid receptor) given its relevance with G×E (childhood trauma) interactions [24] and PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, coded by ADCYAP1 gene, associated with estrogen response) given evidence of sex effects [25].

Genome-wide Association Studies

Despite the still-growing candidate gene literature, there has been a shift away from this design within the field [14], in part due to limitations of candidate gene studies more broadly (e.g., confines of existing knowledge of etiologic processes, small sample sizes, and variability in study quality; see [26] for a cogent overview). Instead, the use of more agnostic approaches has gained momentum since the first PTSD GWAS was published in 2013 [27]. GWAS uses a hypothesis-free approach that permits examination of common SNP variation across the genome. While this literature will undoubtedly continue to grow and shift, four overall conclusions can be drawn at this time. First, although two studies failed to identify SNPs that met genome-wide significance [28, 29], the majority of GWAS have identified significant hits [27, 30-34*], some of which have been internally replicated. Attempts at external replication by other groups (e.g., the RORA variant identified in [27]) have been successful in some [e.g., 35*], but not all [36], samples. Second, GWAS have identified novel variants that had not previously been included in candidate approaches, supporting the unique contributions of this methodology. Third, novel loci identified appear to lie in pathways identified in biologic studies of PTSD (e.g., immune system function [31, 33, 34] ). Fourth, despite novel and biologically relevant findings, there has yet to be replication of identified loci across separate GWAS.

Notably, the two most recent, and largest, GWAS to date [33*, 34*] have utilized recent statistical innovations and moved beyond standard analyses to use multi-ethnic/racial meta-analysis techniques and to examine shared genetic overlap between PTSD and other phenotypes. The first study [33]conducted GWAS analyses individually within four ancestral groups, and then meta-analyzed the separate GWASs. The meta-analysis identified a novel loci, rs6482463, in the PRTFDC1 gene, and showed support for replication in an independent sample. In a cross-disorder analysis leveraging existing GWASs of other psychiatric phenotyes, evidence of some genetic overlap was found with bipolar disorder. The second study [34] found genome-wide significance in one sample for rs159572 in ANKRD55 (associated with autoimmune and inflammatory disorders) in African Americans and rs1108537 in ZNF626 (thought to be involved in the regulation of RNA transcription) in European Americans (EA). However, these findings were not replicated across ancestry groups, in the other sample, nor in the combined transancestral meta-analysis. A cross-disorders analysis did not find any significant genetic overlap with a number of psychiatric conditions but did find evidence of shared genetic overlap for a number of immune-related disorders in the EA sample.

Although GWAS permit examination of many genes, the approach is not without limitations: large samples are needed for adequate power, adjustments for multiple testing must be employed, and identified loci are not necessarily disease-causing polymorphisms but may be in high linkage disequilibrium with the ‘causal’ SNP, which may demonstrate small effects. Thus, efforts to increase sample size will be important for identifying new PTSD genes and the need for large collaborative science is being increasingly recognized [15**].

Other Genomic Platforms

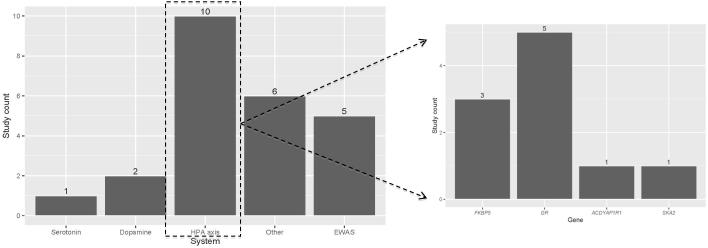

The molecular genetic research evidence has pointed to the importance of examining ways environmental experiences (i.e., trauma exposure) impact outcomes of DNA through changes to the epigenome, and in turn confer risk for PTSD. Epigenetic processes have been proposed as one way the environment may “get under the skin” [37]. Epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation modify DNA structure to permit molecular adaptability (e.g., [38]) and complexity [39], with functional changes in DNA products. Although most epigenetic investigations of PTSD have focused on methylation, it is one of numerous epigenetic processes of likely relevance. As with candidate gene studies, differential methylation in a number of genes and systems has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PTSD, including NR3C1, CRHR1, and FKBP5 (stress response), SLC6A3 and SLC6A4 (neurotransmitter activity), and IGF2 (immune regulation), among others, with about 20 conducted to date (see reviews [40* and 41] and Figure 2). A few studies have also examined epigenome-wide (EWAS) markers. This approach is promising as it offers a more agnostic method of examining epigenetic influences and allows for the potential to identify novel candidate genes and biological pathways implicated in PTSD. Moreover, sample size requirements for EWAS are substantially smaller than for GWAS; while there does not appear to be a specific threshold, published studies have generally included approximately 100 cases, as opposed to the thousands required for GWAS (see [42] for review of EWAS design and power considerations). EWAS have suggested the relevance of methylation of genes involved in immune system functioning (e.g., [43, 44]), as well as promising work in the domain of methylation age (i.e., a model of cellular age using methylation levels, based on theory that chronic stress may accelerate cellular aging; for review see [45]) associated with trauma exposure and PTSD [46, 47].

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Epigenetic Studies of PTSD conducted to date. Figure 2b. Specific candidate genes studied within the HPA axis. System = neurotransmitter system of interest; Gene = HPA axis related gene; EWAS = epigenome-wide association study.

Note: These counts are not exhaustive of all PTSD epigenetic studies and only include those that primarily examined an association and had a control comparison group. Counts for this figure were derived from review article by Zannas and colleagues (2015) as well as an updated review of the literature by author CS.

Epigenetic processes may exert effects through their impact on gene expression [48]. Clear differences in expression patterns between trauma-exposed individuals with and without PTSD have been identified. Specifically, expression within genes involved in HPA-axis [49], immune function [43], and transcription of neural and endocrine proteins [50] differentiate those with and without PTSD. Limited work has examined the link between SNPs implicated in association studies of PTSD and the expression of those same polymorphisms (e.g., PAC1 [25]). Although this work is still in its infancy, these promising genomic platforms have the potential to clarify the biological mechanisms by which trauma exposure impacts propensity for PTSD.

Challenges/Considerations for Genetic Studies of PTSD

In addition to the limitations previously discussed with regard to candidate gene and GWAS designs, unique considerations in genomic studies of PTSD include variations in trauma exposure among cases and controls, differing methods of assessing exposure and symptoms, and variability in considerations such as time elapsed since the trauma that may affect replication success, or lack thereof, across studies. Convergence of agnostic and candidate approaches, particularly those that factor in these considerations, offer new avenues for understanding the etiology of PTSD, including nuances such as how gender, ancestry, age at trauma, trauma type, and post/peri-trauma environments may be critical considerations in the biological underpinnings of PTSD development. Rapid advances in technology and analytic approaches, as well as the development of consortia and large available datasets, provide exciting opportunities in genomic research. It will be important for researchers to continue to conduct investigations that adopt the large-sample, agnostic approach while simultaneously examining more carefully phenotyped smaller sample investigations, as these methods have great potential to be mutually informative and iterative in value. Researchers have pointed to heterogeneity among populations diagnosed with PTSD and genomic studies may provide a way to understand this heterogeneity if PTSD subtypes are appropriately modeled (e.g., [51]).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Converging lines of evidence from genetic epidemiologic and molecular genomic studies underscore the importance of gaining a more thorough understanding of the genetic architecture of PTSD to fully understand its etiology. As the field of psychiatric genomics has increasingly recognized the need for large collaborative science to achieve greater statistical power, great strides have been made through the formation of the Psychiatric Genomics Workgroup (PGC). In 2013 the PTSD workgroup of the PGC was founded [15**], and now includes over 100 members. The current sample size for GWAS meta-analysis is around 20,000 and by October of 2016 it is expected that the group will have approximately 25,000 PTSD cases and nearly double that amount of trauma-exposed controls. The PTSD workgroup of the PGC has also formed numerous other workgroups, including EWAS and gene expression workgroups, which will likely soon yield important breakthroughs in their respective areas.

Another exciting area of development that will benefit the field of genomics of PTSD broadly is that of novel statistical innovations that can be applied to existing GWAS data. For example, analytic techniques are now available that allow for determination of SNP-based heritability (e.g., genome-wide complex trait analysis [GCTA; http://cnsgenomics.com/software/gcta/] and LD score regression [https://github.com/bulik/ldsc) wherein researchers can determine the heritability of their phenotype using measured genes in unrelated individuals. Additionally, techniques such as polygenic risk scores (PRS; http://prsice.info) and cross-trait LD score regression are allowing researchers to ask novel questions about the degree of molecular overlap between phenotypes. Further, as we enter the ‘post-GWAS era’, bioinformatics approaches such as gene enrichment and gene pathway analyses will become critical to advance our understanding of the etiology of PTSD.

Highlights.

Over 100 candidate gene studies have been conducted to date

Candidate gene studies of the HPA-axis system appear to be promising

Genome-wide association studies have identified novel variants of risk

Recent developments include large-scale collaborative efforts for future GWAS

New approaches examine heritability in unrelated individuals and molecular overlap between phenotypes

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sheerin, Mackenzie Lind, and Dr. Bountress are support by National Institute of Health T32 grants MH020030 (CS and ML) and MH18869 (KB). Dr. Nugent is supported by National Institute of Health grants R01MH105379, R01MH108641, R01MH095786, K24HL130451, R01HD071982. Dr. Amstadter is supported by National Institute of Health grants R01AA020179, K02 AA023239, BBRF 20066, R01MH101518, and P60MD002256.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest ** of outstanding interest

- [1].American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5edn American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Friedman MJ. Finalizing PTSD in DSMD5: Getting here from there and where to go next. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):548–556. doi: 10.1002/jts.21840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kessler RC. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol Trauma. 2008;1(1):3–36. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. doi: 10.1037/1942-9681.s.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].True WR, Rice J, Eisen SA, Heath AC, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Nowak J. A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(4):257–264. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sartor CE, McCutcheon VV, Pommer NE, Nelson EC, Grant JD, Duncan AE, Waldron M, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Heath AC. Common genetic and environmental contributions to posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence in young women. Psychol Med. 2011;41(7):1497–1505. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lambert JE, Holzer J, Hasbun A. Association between parents’ PTSD severity and children's psychological distress: A meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27(1):9–17. doi: 10.1002/jts.21891. doi: 10.1002/jts.21891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Leen-Feldner EW, Feldner MT, Knapp A, Bunaciu L, Blumenthal H, Amstadter AB. Offspring psychological and biological correlates of parental posttraumatic stress: Review of the literature and research agenda. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1106–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.09.001. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Afifi TO, Asmundson GJG, Taylor S, Jang KL. The role of genes and environment on trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of twin studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Eisen SA, True W, Tsuang MT, Meyer JM, Henderson WG. Do genes influence exposure to trauma? A twin study of combat. Am J Med Genet. 1993;48(1):22–27. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320480107. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320480107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sartor CE. Common heritable contributions to low-risk trauma, high-risk trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):293. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1385. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stein MB, Jang KL, Taylor S, Vernon PA, Livesley WJ. Genetic and environmental influences on trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1675–1681. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [**13].Smoller JW. The Genetics of Stress-Related Disorders: PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;41(1):297–319. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.266. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.266. This recent review summarizes genetic contributions for PTSD, MDD and anxiety diosrders covering genetic epidemiology, the role of common genetic variation, the role of rare and structural variation, and gene-environment interaction. This review also provides a useful primer on research questions and metholodogies used in the field of psychiatric genetics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cornelis MC, Nugent NR, Amstadter AB, Koenen KC. Genetics of post-traumatic stress disorder: Review and recommendations for genome-wide association studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(4):313–326. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0126-6. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [**15].Logue MW, Amstadter AB, Baker DG, Duncan L, Koenen KC, Liberzon I, Miller MW, Morey RA, Nievergelt CM, Ressler KJ, et al. The psychiatric genomics consortium posttraumatic stress disorder workgroup: Posttraumatic stress disorder enters the age of large-scale genomic collaboration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(10):2287–2297. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.118. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.118. This paper represents the first publication of the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium for PTSD (PGC-PTSD). It reviews genome-wide association studies conducted to date and describes the formation of the consortium for future large-scale study of PTSD genetics, detailing the analysis pipeline, the samples included thus far, planned analyses, and PGC-PTSD subgroups of interest (e.g., epigenetics and neuroimaging workgroups) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [*16].Voisey J, Young RM, Lawford BR, Morris CP. Progress towards understanding the genetics of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(8):873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.014. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.014. In addition to reviewing candidate gene and genome-wide associaiton studies, this review also details gene-environment interaction studies, summarizes the PTSD epigenetic studies conducted to date, and notably, also reviews the small, but interesting literature on the genetics of treatment response for anxiety disorders and PTSD, which has focused on brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), endogeneous human cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1), and the SCL6A4 promoter polymorphic region. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [*17].Almli LM, Fani N, Smith AK, Ressler KJ. Genetic approaches to understanding post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;17(02):355–370. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001090. doi: 10.1017/s1461145713001090. Provides a comprehensive review of the genetics of PTSD, particularly detailing findings of candidate gene studies including neuroimaging studies of candidate genes as well as genome-wide association studies and epigenetic regulation findings. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Navarro-Mateu F, Escámez T, Koenen KC, Alonso J, Sánchez-Meca J. Meta-analyses of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphisms and post-traumatic stress disorder. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066227. e66227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gressier F, Calati R, Balestri M, Marsano A, Alberti S, Antypa N, Serretti A. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:645–653. doi: 10.1002/jts.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang T. Does BDNF Val66Met polymorphism confer risk for posttraumatic stress disorder? Neuropsychobiology. 2015;71(3):149–153. doi: 10.1159/000381352. doi: 10.1159/000381352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bruenig D, Lurie J, Morris CP, Harvey W, Lawford B, Young RM, Voisey J. A Case-control study and meta-analysis reveal BDNF val66Met is a possible risk factor for PTSD. Neural Plast. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6979435. doi: 10.1155/2016/6979435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li L, Bao Y, He S, Wang G, Guan Y, Ma D, Wang P, Huang X, Tao S, Zhang D, et al. The association between genetic variants in the dopaminergic system and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(11):e3074. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003074. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23*].Castro-Vale I, van Rossum EFC, Machado JC, Mota-Cardoso R, Carvalho D. Genetics of glucocorticoid regulation and posttraumatic stress disorder—What do we know? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;63:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.005. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.005. This review article focuses on the genetic factors associated with glucocorticoid function in PTSD, from the overall perspective of HPA-axis functioning. It covers the underlying processes involved with glucocorticoids, ncluding the corticotrophin-releasing hormong, oxytocin pathway, glucocorticoid recpetors, and regulators suchas FKBP5. The review discusses polymorphisms that have been shown to affect HPA-axis sensitivity and gene-environment interaction studies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Watkins LE, Han S, Harpaz-Rotem I, Mota NP, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Gelernter J, Pietrzak RH. FKBP5 polymorphisms, childhood abuse, and PTSD symptoms: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;69:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.001. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hammack SE, May V. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide in stress-related disorders: Data convergence from animal and human studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2015;78:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.003. doi: 10.2026/j.biopsych.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dick DM, Latendresse SJ, Riley B. Incorporating genetics into your studies: A guide for social scientists. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00017. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Logue MW, Baldwin C, Guffanti G, Melista E, Wolf EJ, Reardon AF, Uddin M, Wildman D, Galea S, Koenen KC. A genome-wide association study of post-traumatic stress disorder identifies the retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) gene as a significant risk locus. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(8):937–942. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.113. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wolf EJ, Rasmusson AM, Mitchell KS, Logue MW, Baldwin CT, Miller MW. A genome-wide association study of clinical symptoms of dissociation in a trauma-exposed sample. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(4):352–360. doi: 10.1002/da.22260. doi: 10.1002/da.22260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ashley-Koch AE, Garrett ME, Gibson J, Liu Y, Dennis MF, Kimbrel NA, Beckham JC, Hauser MA. Genome-wide association study of posttraumatic stress disorder in a cohort of Iraq–Afghanistan era veterans. J Affect Disord. 2015;184:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.049. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xie P, Kranzler HR, Yang C, Zhao H, Farrer LA, Gelernter J. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.013. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Guffanti G, Galea S, Yan L, Roberts AL, Solovieff N, Aiello AE, Smoller JW, De Vivo I, Ranu H, Uddin M, et al. Genome-wide association study implicates a novel RNA gene, the lincRNA AC068718.1, as a risk factor for post-traumatic stress disorder in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):3029–3038. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.08.014. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Almli LM, Stevens JS, Smith AK, Kilaru V, Meng Q, Flory J, Abu-Amara D, Hammamieh R, Yang R, Mercer KB, et al. A genome-wide identified risk variant for PTSD is a methylation quantitative trait locus and confers decreased cortical activation to fearful faces. Am J Med Genet. 2015;168(5):327–336. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32315. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [*33].Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Mustapic M, Yurgil KA, Schork NJ, Miller MW, Logue MW, Geyer MA, Risbrough VB, O’Connor DT, et al. Genomic predictors of combat stress vulnerability and resilience in U.S. Marines: A genome-wide association study across multiple ancestries implicates PRTFDC1 as a potential PTSD gene. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.017. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.017. This paper represents the first multi-ethnic/racial genome-wide association study of PTSD. The meta-analysis identified the phosphoribosyl transferase domain contining 1 gene (PRTFDC1, rs6482463) which was seen across ancestry groups and showed some evidence for replication with an independent military cohort. Notably, this study also examined 25 putative PTSD genes from the literature and found nominally significant SNPs for the majority of them and conducted a cross-disorder analysis of polygenic risk score from GWASs of BPD, MDD, and SCZ, finding some overlap with BPD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [*34].Stein MB, Chen C-Y, Ursano RJ, Cai T, Gelernter J, Heeringa SG, Jain S, Jensen KP, Maihofer AX, Mitchell C, et al. Genome-wide association studies of posttraumatic stress disorder in 2 cohorts of US Army soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):695. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0350. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0350. This is the largest and most recent genome-wide association study published to date. This study found genome-wide signfiicance for ANKRD55 on chromosome 5 (rs159572) in the AA sample and ZNF626 on chromosome 19 (rs11085374) in the EA sample, although the results were not found across the samples. Moreover, similar results were not found for either variant in the replication sample, other ancestry groups, or in the transancestral meta-analyses. This study also assessed genetic correlations between PTSD and six other psychiatric disorders, and did not find a significant correlation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [*35].Lowe SR, Meyers JL, Galea S, Aiello AE, Uddin M, Wildman DE, Koenen KC. RORA and posttraumatic stress trajectories: main effects and interactions with childhood physical abuse history. Brain Behav. 2015;5(4):e00323. doi: 10.1002/brb3.323. doi: 10.1002/brb3.323. This study expanded the literature that has found an association of the RORA gene with PTSD as well as the gene by environment studies by examining the association with posttraumatic sress trajectories (low, decreasing, increasing, and high symptoms), at three time points. They found that the RORA SNP rs893260 was significantly predictive of the high trajectory, and remained following correction for multiple testing. this SNP also evidenced an interaction effect, wherein the genetic risk was moer strongly associated with membership in all classes aside from the low trajectory group for participants with higher levels of childhood physical abuse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Guffanti G, Ashley-Koch AE, Roberts AL, Garrett ME, Solovieff N, Ratanatharathorn A, De Vivo I, Dennis M, Ranu H, Smoller JW, et al. No association between RORA polymorphisms and PTSD in two independent samples. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(10):1056–1057. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.19. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Toyokawa S, Uddin M, Koenen KC, Galea S. How does the social environment ‘get into the mind’? Epigenetics at the intersection of social and psychiatric epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.036. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, McCarthy MI, Ramos EM, Cardon LR, Chakravarti A, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461(7265):747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, Ye Z, Ngo Q-M, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462(7271):315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [*40].Zannas AS, Provençal N, Binder EB. Epigenetics of posttraumatic stress disorder: Current Evidence, challenges, and future Directions. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(5):327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.003. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.003. This detailed review provides an overview of epigenetic studies with regard to PTSD and presents the existing epigenetic studies of PTSD conducted to date. Additionally, this review discusses the unique challenges and limitations of epigenetic research (e.g., tissue specificity, translating evidence across species, and the need to assess longitudinal epigenetic changes over time) with a focus on important directions for future work in this area. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].McGowan PO. Epigenomic mechanisms of early adversity and HPA dysfunction: Considerations for PTSD research. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00110. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rakyan VK, Down TA, Balding DJ, Beck S. Epigenome-wide association studies for common human diseases. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12:529–541. doi: 10.1038/nrg3000. doi: 10.1038/nrg3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Uddin M, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, Koenen KC, Pawelec G, de los Santos R, Goldmann E, Galea S. Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(20):9470–9475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910794107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Smith AK, Conneely KN, Kilaru V, Mercer KB, Weiss TE, Bradley-Davino B, Tang Y, Gillespie CF, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Differential immune system DNA methylation and cytokine regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Med Genet. 2011;156:700–708. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31212. doi: 10.1002/ajmp.b.31212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Miller MW, Sadeh N. Traumatic stress, oxidative stress and post-traumatic stress disorder: neurodegeneration and the accelerated-aging hypothesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1156–1162. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Boks MP, Mierlo HCv, Rutten BPF, Radstake TRDJ, De Witte L, Geuze E, Horvath S, Schalkwyk LC, Vinkers CH, Broen JCA, et al. Longitudinal changes of telomere length and epigenetic age related to traumatic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.011. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Hayes JP, Sadeh N, Schichman SA, Stone A, Salat DH, Milberg W, McGlinchey R, Miller MW. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and neural integrity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.020. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rampp C, Binder EB, Provençal N. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. Vol. 128. Elsevier BV; 2014. Epigenetics in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; pp. 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yehuda R, Flory JD, Pratchett LC, Buxbaum J, Ising M, Holsboer F. Putative biological mechanisms for the association between early life adversity and the subsequent development of PTSD. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212(3):405–417. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1969-6. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1969-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Segman RH, Shefi N, Goltser-Dubner T, Friedman N, Kaminski N, Shalev AY. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles identify emergent post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma survivors. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(5):500–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001636. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Krueger RF, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, Koenen KC. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the genetic structure of comorbidity. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119(2):320–330. doi: 10.1037/a0019035. doi: 10.1037/a0019035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]