Abstract

We report analytic and consensus processes that produced recommendations for neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups (ypTNM) of esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancer for AJCC/UICC cancer staging manuals, 8th edition. The Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration (WECC) provided data for 22,654 patients with epithelial esophageal cancers; 7,773 had pathologic assessment after neoadjuvant therapy. Risk-adjusted survival for each patient was developed. Random Forest analysis identified data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups wherein survival decreased monotonically with increasing group, was distinctive between groups, and homogeneous within groups. An additional analysis produced data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups based only on ypT, ypN, and ypM categories. The AJCC Upper GI Task Force, by smoothing, simplifying, expanding, and assessing clinical applicability, produced consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups. Grade and location were much less discriminating for stage grouping ypTNM than pTNM. Data-driven stage grouping without grade and location produced nearly identical groups for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. However, ypTNM groups and their associated survival differed from pTNM. The need for consensus process was minimal. The consensus groups, identical for both cell types were as follows: ypStage I comprised ypT0-2N0M0; ypStage II ypT3N0M0; ypStage IIIA ypT0-2N1M0; ypStage IIIB ypT3N1M0, ypT0-3N2, and ypT4aN0M0; ypStage IVA ypT4aN1-2, ypT4bN0-2, and ypTanyN3M0; and ypStage IVB ypTanyNanyM1. Absence of equivalent pathologic (pTNM) categories for the peculiar neoadjuvant pathologic categories ypTisN0-3M0 and ypT0N0-3M0, dissimilar stage group compositions, and markedly different early- and intermediate-stage survival necessitated a unified, unique set of stage grouping for patients of either cell type who receive neoadjuvant therapy.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, esophagectomy, oncology, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Pathologic stage after neoadjuvant therapy (ypTNM), by tradition, shared pathologic stage after esophagectomy alone (pTNM). However, this concept is in question.1 Post-7th edition AJCC instructions and goals of the Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration (WECC)2 were to develop, if indicated, separate neoadjuvant pathologic staging recommendations for cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction for the 8th edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Data provided by WECC3,4 served as substrate for a data-driven machine-learning analysis producing data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups. An additional machine-learning analysis produced data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups based only on ypT, ypN, and ypM categories. The AJCC Upper GI Task Force reviewed these and, by smoothing, simplifying, expanding, and assessing clinical applicability, produced consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups.

This manuscript reports these data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups, data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups, and consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups. Finally, to simplify prognostication, the consensus pTNM5 stage group with equivalent survival to each consensus ypTNM stage group was identified.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

At 33 WECC institutions (Supporting Information Appendix S1), 22,654 patients were treated for epithelial esophageal cancers.3 Of these 22,123 had treatment, survival, and pT data available. Among the latter, 7,773 had pathologic staging after neoadjuvant therapy. Patient, cancer, and survival data have been published.2

Endpoint

The endpoint was all-cause mortality from first management decision. Median potential follow-up was 8.9 years6; however, median actual follow-up for surviving patients was 2.5 years, with 25% followed more than 5.1 years and 10% more than 8.4 years.3

Data

Data were collected using a common format with standardized definitions (Supporting Information Table S1). The Case Cancer Institutional Review Board of Case Western Reserve University and Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the entire project.

Data analysis

Analytic strategy

Risk-adjusted survival for each patient was developed. Data-driven groups were formulated such that 1) survival decreased monotonically with increasing group number, and 2) survival of each group was distinctive, with no more than a 5% difference. ypTNM categories comprising each group were then exposed. Homogeneity of survival within groups was determined.

Risk-adjusted survival

Random Survival Forest (RSF) methodology was used to estimate nonparametric risk-adjusted and cross-validated survival for each patient.7,8 Thirty-nine dichotomous, polytomous, ordinal, and continuous variables were used (Supporting Information Table S2) in separate analyses for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

All computations used open source randomForestSRC R-software under default settings.9 Missing data for all other variables were pre-imputed without outcome information by RF imputation methodology, missForest.10,11 One thousand survival trees were grown using log-rank splitting. Each tree was constructed using an independent bootstrap sample of size 22,123; on average, each bootstrap sample contained 63% of the patients. The remaining unused patients (37%) were referred to as out-of-bag (OOB) observations. Each tree and its corresponding OOB observations were used to calculate a patient-specific risk-adjusted OOB (cross-validated) survival function for stage grouping and patient-specific mortality value (integrated cumulative hazard for each patient) for analysis of homogeneity.7

Data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic staging

RSF analysis produced 24 subsets of squamous cell carcinoma patients and 19 for adenocarcinoma (Supporting Information Table S3 and Figs. S1 and S2), with constraints such that only subsets with a sample size of 20 patients or more were permitted. Stage groups were then formed by iteratively merging these subsets by closeness and individual patient survival by closeness, defined as the root-mean-squared-error difference between OOB survival functions from 3 to 10 years, until no more than a 5% difference between adjacent groups, above and below, was observed.

Data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic staging

UICC requirements for pure ypTNM groupings, a second RSF analysis, was performed to produce data-driven anatomic pathologic stage groupings. Grade and location were used in risk adjustment.

Consensus neoadjuvant pathologic staging

The AJCC Upper GI Task Force reviewed cancer categories and both data-driven analyses. The consensus process of merging, splitting, and smoothing data-driven groups while maintaining clinical relevance and minimizing drift from data-driven groupings produced consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups.

Homogeneity

Within each data-driven, anatomic, and consensus stage group, homogeneity was accessed as follows. OOB patient survival was analyzed with respect to the 39 independent variables using RF regression. Regression forests of 1,000 random regression trees were grown using mean-squared-error splitting. From each RF regression, variable importance (VIMP) of each variable was calculated by measuring the increase in OOB mean-squared error when the variable was removed from the analysis,8 and standardized by dividing VIMP by the variance of OOB patient mortality multiplied by 100. Standardized VIMP measured the relative importance of each independent variable in predicting OOB patient mortality within a stage group. If a group is homogeneous, standardized VIMP for all cancer facts should be near zero. Values under 5% were deemed to be non-significant.12

Equivalence of survival between consensus pTNM and consensus ypTNM stage groups

For each consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage group, the consensus pTNM5 stage group with equivalent survival profile was identified.

RESULTS

Data-driven Neoadjuvant Pathologic Stage Groups

Seven data-driven stage groups, presented simply as cardinal numbers, were identified for squamous cell carcinoma (Table 1) and 5 for adenocarcinoma (Table 2). Risk-adjusted survival for squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 1A) and adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1B) monotonically decreased with increasing cardinal number and was distinctive between groups. Homogeneity was excellent for all groups except 4 and 5 for adenocarcinoma (Supporting Information Figs. S3A and S4A). However, further refinement of these groups by ypN+ subgrouping would be statistically important but clinically irrelevant because survival was so poor.

Table 1.

Data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups for squamous cell carcinoma

| Analysis Group |

ypT | ypN | ypM | ypGrade | ypLocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T2 | N0 | M0 | G1 | Upper/Middle |

| 2 | T2 | N0 | M0 | G2–3 | Lower |

| 3 | T0 | N0 | M0 | N/A | Any |

| T1 | N0 | M0 | Any | Any | |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | G2 | Upper/Middle | |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | G1 | Upper/Middle | |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | G2 | Lower | |

| 4 | T2 | N0 | M0 | G2–3 | Upper/Middle |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | G3 | Lower | |

| 5 | T3 | N0 | M0 | G2–3 | Upper/Middle |

| T0–2 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

| 6 | T2 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | Any | |

| T3 | N1–2 | M0 | Any | Any | |

| 7 | T4a | N1 | M0 | Any | Any |

| Any | N3 | M0 | Any | Any | |

| Any | Any | M1 | Any | Any |

Table 2.

Data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups for adenocarcinoma

| Analysis Group | ypT | ypN | ypM | ypG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T0 | N0 | M0 | N/A |

| T1 | N0 | M0 | Any | |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | G1–2 | |

| 2 | T2 | N0 | M0 | G3 |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | Any | |

| 3 | T0–2 | N1 | M0 | Any |

| T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | |

| T1 | N2 | M0 | Any | |

| 4 | T2 | N2 | M0 | Any |

| T3 | N1–2 | M0 | Any | |

| T4a | N1 | M0 | Any | |

| 5 | Any | N3 | M0 | Any |

| Any | Any | M1 | Any |

Fig. 1.

Risk-adjusted survival of data-driven neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups. A, Squamous cell carcinoma. B, Adenocarcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Grade and location played a limited role in groups 1–5. Only for ypT2-3N0M0 cancers did it play a role, and not in an ordered progression; these cancers were broadly spread through Group 1 (ypT2N0M0G1 upper/middle esophagus), Group 2 (ypT2N0M0G2-3 lower esophagus), Group 3 (ypT2N0M0G2 upper/middle esophagus, ypT3N0M0 upper/middle esophagus, and ypT3N0M0G2 lower esophagus), Group 4 (ypT2N0M0G2-3 upper/middle esophagus and ypT3N0M0G3 lower esophagus), and group 5 (ypT3N0M0G2-3 upper/middle esophagus), with few entries per group and poor arrangement by grade and location. Group 3 also contained ypT0-1N0M0 and Group 5 ypT1N2M0. Advanced cancers (Groups 6 and 7) grouped more orderly. There were too few ypTisN0-2M0, ypT1N2M0, ypT2-3N0M0G1 lower esophagus, ypT4aN2M0, and ypT4bN0-2M0 cancers to group.

Adenocarcinoma

Grade played a limited role in stage grouping, useful only in ypT2N0M0 patients. Group 1 was composed of ypT0-2N0M0 cancers confined to the esophageal wall, except for ypT2N0M0G3 cancers, which with ypT3N0M0 cancers comprised Group 2. Group 3 was restricted to cancer confined to the esophageal wall with ypN1 regional nodal category and ypT4aN0M0 and ypT1N2M0. Group 4 was composed of ypT2N2M0, ypT3N1-2M0, and ypT4aN1M0 cancers. Group 5 comprised ypTanyN3M0 and ypM1. There were too few ypTisN0-2M0, ypT0N2M0, ypT4aN2M0, and ypT4bN0-2M0 patients to group.

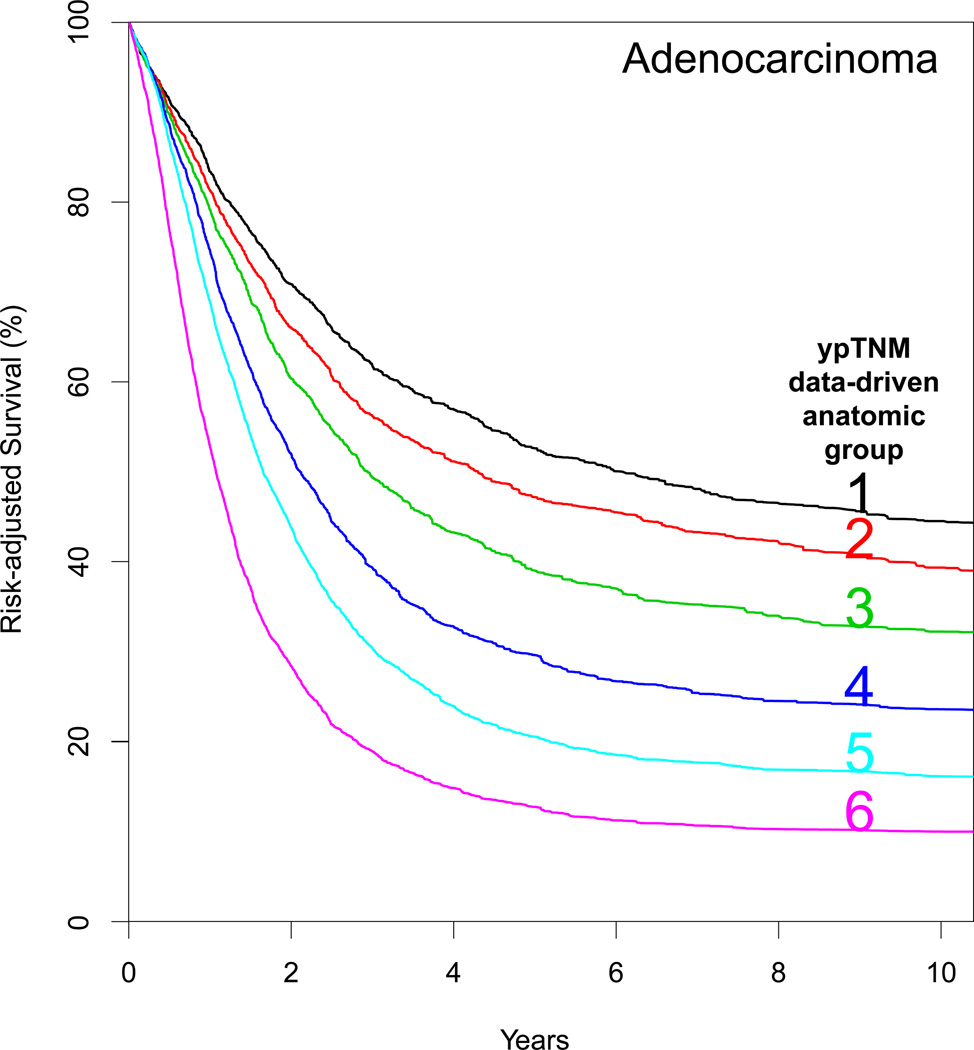

Data-driven Anatomic Neoadjuvant Pathologic Stage Groups

Five data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups, presented simply as cardinal numbers, were identified for squamous cell carcinoma (Table 3) and 6 for adenocarcinoma (Table 4). Risk-adjusted survival for squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 2A) and adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2B) monotonically decreased, was distinctive between groups, and was homogeneous within groups (Supporting Information Figs. S3B and S4B).

Table 3.

Data-driven anatomic and consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups for squamous cell carcinoma

| Analysis Group |

ypT | ypN | ypM | Consensus Stage Group |

Consensus pTNM Equivalent Groupa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T0 | N0 | M0 | I | IIB | |

| X | Tis | N0 | M0 | I | IIB | |

| T1–2 | N0 | M0 | I | IIB | ||

| 2 | T3 | N0 | M0 | II | —b | |

| 3 | T0 | N1 | M0 | IIIA | IIIA | |

| X | Tis | N1 | M0 | IIIA | IIIA | |

| T1–2 | N1 | M0 | IIIA | IIIA | ||

| 4 | T4a | N0 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | ||

| X | T0–1 | N2 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | |

| T2–3 | N2 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | ||

| 5 | T4a | N1 | M0 | IVA | IVA | |

| X | T4a | N2 | M0 | IVA | IVA | |

| X | T4a | NX | M0 | IVA | IVA | |

| X | T4b | N0–1 | M0 | IVA | IVA | |

| Any | N3 | M0 | IVA | IVA | ||

| Any | Any | M1 | IVB | IVA | ||

Note: X = not in data-driven analysis.

. Equivalent survival with pTNM consensus groups.

. No survival equivalent pTNM group.

Table 4.

Data-driven anatomic and consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups for adenocarcinoma

| Analysis Group |

ypT | ypN | ypM | Consensus Stage Group |

pTNM Equivalent Groupa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T0 | N0 | M0 | I | IIA | |

| X | Tis | N0 | M0 | I | IIA | |

| T1 | N0 | M0 | I | IIA | ||

| 2 | T2 | N0 | M0 | I | IIA | |

| 3 | T3 | N0 | M0 | II | IIB | |

| 4 | T0 | N1 | M0 | IIIA | IIIA | |

| X | Tis | N1 | M0 | IIIA | IIIA | |

| T1–2 | N1 | M0 | IIIA | IIIA | ||

| T4a | N0 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | ||

| T1 | N2 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | ||

| 5 X | T0–1 | N2 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | |

| T2 | N2 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | ||

| T3 | N1–2 | M0 | IIIB | IIIB | ||

| T4a | N1 | M0 | IVA | IVA | ||

| 6 X | T4a | N2 | M0 | IVA | IVA | |

| X | T4b | N0–2 | M0 | IVA | IVA | |

| Any | N3 | M0 | IVA | IVA | ||

| Any | Any | M1 | IVB | IVA | ||

Note: X = not in data-driven analysis.

. Equivalent survival with pTNM consensus groups.

Fig. 2.

Risk-adjusted survival of data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups. A, Squamous cell carcinoma. B, Adenocarcinoma.

The groups were identical for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma except that ypT2N0M0 moved from Group 1 squamous cell carcinoma to Group 2 adenocarcinoma as the sole entry, which then increased the cardinal number. ypT4aN0M0 and ypT4aN1M0 squamous cell carcinoma moved to one group lower in adenocarcinoma.

Consensus Neoadjuvant Pathologic Stage Groups

The consensus process produced identical groupings for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma by using the data-driven anatomic neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups (Tables 3 and 4). The only step required was combining ypT2N0M0 adenocarcinoma, the sole component of Group 2, with Group 1 cancers to form Consensus group I. Thus, Consensus group I was ypT0-2N0M0; Group II was ypT3N0M0; Group IIIA was ypT1-2N1M0; Group IIIB was ypT0-3N2, ypT3N1M0, and ypT4aN0M0; and Group IV was ypT4aN1-2M0, ypT4bN0-2M0, ypanyTN3M0, and ypM1.

Risk-adjusted survival for squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 3A) and adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3B) monotonically decreased with increasing cardinal number and was distinctive between groups. Homogeneity was excellent for all groups except ypIIIB, ypIVA, and ypIVB (Supporting Information Figs. S3C and S4C). However, further refinement of these groups by ypN+ subgrouping would be statistically important but clinically irrelevant because survival was so poor.

Fig. 3.

Risk-adjusted survival of consensus neoadjuvant pathologic stage groups. A, Squamous cell carcinoma. B, Adenocarcinoma.

Equivalence of Survival between Consensus pTNM and ypTNM Stage Groups

For squamous cell carcinoma, survival of ypTNM stage group I was equivalent to pTNM stage group IIB, but survival for ypTNM stage group II was intermediate between pTNM stage groups IIB and IIIA. Survival for ypTNM stage groups IIIA through IVB were equivalent to the same pTNM stage groups.

For adenocarcinoma, survival of ypTNM stage group I was equivalent to pTNM stage group IIA, and ypTNM stage group II was equivalent to pTNM stage group IIB. Survival of ypTNM stage group IIIA-IVB were equivalent to the same pTNM stage groups.

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

Unique pTNM categories (ypTisN0-3M0 and ypT0N0-3M0) produced by the differential effects of neoadjuvant therapy on T, N, and M, dissimilar stage group compositions, and markedly different survival profiles necessitated a unified, unique set of stage groupings for patients of either cell type who receive neoadjuvant therapy. Grade and location were not sufficiently discriminatory for ypTNM stage grouping. Survival of earlier ypTNM classifications is markedly less than equivalent pTNM groups, but that for stage groups IIIA and IIIB were equivalent.

ypT0-2 cancers have similar survival for each N category; ypT0-2N0M0 comprise ypStage I; ypT0-2N1M0 comprise ypStage IIIA; ypT0-2N2M0 plus ypT3N1-2M0 and ypT4aN0M0 comprise ypStage IIIB; and ypT0-2N3 plus ypT3N3M0, ypT4aN1-3, and ypT4bN0-3M0 comprise ypStage IVA. ypT3N0M0 cancers are the sole constituent of ypStage II. All ypM1 cancers are ypStage IVB.

The Literature

Although developed using patients undergoing esophagectomy with no preoperative therapy (pTNM),12 use of 7th edition stage groups by two institutions demonstrated monotonically decreasing survival with increasing stage group for patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy (ypTNM).13,14 However, these single-institution studies were too small to resolve distinctiveness between groups. There was no attempt to access homogeneity within groups.

A single-institution study using patients later submitted to the WECC database explored ypTNM0 subgroup survival and compared these results with equivalent pTNM subgroup survival.15 Generally, survival of ypTNM patients mirrored that of equivalent pTNM patients. Those not downstaged (ypT3-4N+M0) had dismal survival. However, downstaged subgroups ypT0N0M0 (22 patients), ypT1-2N0M0 (33 patients), ypT1-2N1M0 (49 patients), and ypT3-4N0M0 (36 patients) had better survival than expected from the overall WECC data. Although not evaluated, survival appeared to decrease with increasing T and N. It was beyond the scope of the institution’s dataset and analysis to examine distinctiveness and homogeneity. The survival discrepancy between this and the present publication is explained in part by the small, single-institution nature of this series, the equivalence tested in responders only, and the differential, random patient response to neoadjuvant therapy.

In a much larger series, again using patients later submitted to the WECC database, survival of early and intermediate 6th edition staged patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy (ypTNM) was significantly worse than for equivalent pTNM stage.16 Again, regardless of treatment, advanced-stage patients had similar dismal survival. These results were in keeping with the present publication. The authors realized the deficiencies of stage grouping in neoadjuvant patients and concluded that although pTNM “continues to predict survival,” incorporating other variables, such as pathologic response, into stage groupings would “better predict patient outcome.”

A much smaller single-institution study determined that in ypN0 patients undergoing complete resection (R0) following neoadjuvant therapy, survival was best predicted by pathologic response and not ypT category.17 Interestingly, for improving prognostication, both papers suggested modifying pTNM rather than developing separate ypTNM stages.

Strengths and Limitations

Neoadjuvant data were coarse and did not include entries such as agents, dosages, radiation doses and fields, schedules, and time between completion of induction therapy and esophagectomy. Risk adjustment considered only that neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy were administered and not type of regime used. Risk adjustment accounted for cTNM; however, there was no direct mapping for each patient of cTNM and ypTNM.

Many believe that cancer-specific survival represents the ultimate disease-specific survival. However, this soft endpoint is plagued by our ability to detect persistence of cancer after treatment. Once patient demographics, comorbidities, and treatments are accounted for (risk-adjusted survival), and in this analysis, continent and institution as well, the residual information contained in all-cause mortality becomes a better endpoint.18,19

Although the strength of WECC is worldwide representation, this also imposes limitations related to institutional, country, and continent heterogeneity of etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and pathologic characterization of esophageal cancer. Treatment of adenocarcinoma, for example, appeared to be more consistent across continents and sites than treatment of squamous cell carcinoma.

Imputation was necessary for missing data in some risk-adjustment variables, and some patients who did not have complete pTNM data or survival information were excluded. Although we attempted to incorporate less invasive treatments, the number of patients receiving such treatment was small.

Clinical Implications

Today, patients with clinically advanced-stage esophageal cancer (cTNM) are likely to be offered neoadjuvant therapy in hopes of improving survival over those patients receiving esophagectomy alone.20 Currently, the response to neoadjuvant therapy is a random event, and many patients do not realize a meaningful survival benefit. However, prognostication is specific for these patients with the AJCC adoption of these 8th edition neoadjuvant recommendations. The role of these recommendations in additional treatment planning is currently limited. However, with advances in therapy and the advent of precision cancer care, they may play a future role.

Conclusions

The assumption that patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy (ypTNM) and those receiving esophagectomy alone (pTNM) can share stage groups is incorrect for early and intermediate ypTNM stage groups. Absence of equivalent pathologic (pTNM) categories for the peculiar neoadjuvant pathologic categories ypTisN0-3M0 and ypT0N0-3M0, dissimilar stage group compositions, and markedly different early- and intermediate-stage survival profiles necessitated a single, unique set of stage grouping for patients of either cell type who receive neoadjuvant therapy.

Prognostication is possible, but survival is reduced from what has been classically quoted for early and intermediate pTNM stage groups. Persistent regional lymph node metastases (ypN+) portend poor survival, and sterilization of metastatic regional lymph nodes (ypN0) does not equate with cure. Patients with ypN0 cancers confined to the esophageal wall or those with complete response have an intermediate survival regardless of ypT.

Although separate ypTNM stage groups appear to complicate patient care, this is a small and important step in pursuit of precision care for esophageal cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funded in part by 1) the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus (ISDE), 2) the Daniel and Karen Lee Chair in Thoracic Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic (TWR), 3) the Kenneth Gee and Paula Shaw, PhD, Chair in Heart Research at the Cleveland Clinic (EHB), and 4) Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Services (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the ISDE, Cleveland Clinic, or the NIH.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conception or design of the experiment(s), or collection and analysis or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting the manuscript or revising its intellectual content: Rice, Ishwaran, and Blackstone. Approval of the final version of the submitted manuscript: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strong VE, D'Amico TA, Kleinberg L, Ajani J. Impact of the 7th Edition AJCC staging classification on the NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology for gastric and esophageal cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:60–66. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice TW, Blackstone EH. Esophageal cancer staging: past, present, and future. Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice TW, Apperson-Hansen C, DiPaola LM, et al. Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration: clinical staging data. Dis Esophagus. 2016 doi: 10.1111/dote.12493. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice TW, Lerut TEMR, Orringer MB, et al. Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration: neoadjuvant pathologic staging data. Dis Esophagus. 2016 doi: 10.1111/dote.12513. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice TW, Chen L-Q, Hofstetter WL, et al. Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration: pathologic staging data. Dis Esophagus. 2016 doi: 10.1111/dote.12520. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman AI. Eventcharts: visualizing survival and other timed-event data. American Statistician. 1992;46:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Random survival forests. Ann Appl Stat. 2008;2:841–860. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB. RandomForestSRC: Random forests for survival, regression and classification (RF-SRC) R package version 2.1.0. 2016 http://cran.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stekhoven DJ, Buhlmann P. MissForest--non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:112–118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang F, Ishwaran H. Random forest missing data algorithms. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/sam.11348. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Ishwaran H, Blackstone EH. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: data-driven staging for the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Staging Manuals. Cancer. 2010;116:3763–3773. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta SP, Jose P, Mirza A, Pritchard SA, Hayden JD, Grabsch HI. Comparison of the prognostic value of the 6th and 7th editions of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM staging system in patients with lower esophageal cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:182–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CC, Cheng JC, Tsai CL, et al. Pathological stage after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and esophagectomy superiorly predicts survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies AR, Gossage JA, Zylstra J, et al. Tumor stage after neoadjuvant chemotherapy determines survival after surgery for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2983–2990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.9070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swisher SG, Hofstetter W, Wu TT, et al. Proposed revision of the esophageal cancer staging system to accommodate pathologic response (pP) following preoperative chemoradiation (CRT) Ann Surg. 2005;241:810–817. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161983.82345.85. discussion 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider PM, Baldus SE, Metzger R, et al. Histomorphologic tumor regression and lymph node metastases determine prognosis following neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for esophageal cancer: implications for response classification. Ann Surg. 2005;242:684–692. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000186170.38348.7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black WC, Haggstrom DA, Welch HG. All-cause mortality in randomized trials of cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:167–173. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, Topol EJ. Cause of death in clinical research: time for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:618–620. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJ, Hulshof MC, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.