Abstract

Aims

We describe choice of first‐line antihypertensive drug therapy and uptake of fixed‐dose combinations (FDCs) in Australia, and investigate the impact of initiation on FDCs and other non‐recommended first‐line therapies on treatment discontinuation.

Method

This was a population‐based retrospective cohort study using a random 10% sample of persons dispensed an Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme listed medicine from 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2014. The primary outcomes were adherence to Australian recommendations at initiation of antihypertensive therapy, discontinuation of initial therapy and discontinuation of any therapy in the first year after initiation.

Results

In our sample of 55 937 persons initiating therapy, 42.0% did so outside Australian recommendations, including not initiating on recommended monotherapy (26.3%) and not initiating on the lowest recommended dose (30.6%). Only 1.7% of individuals who were dispensed an FDC established therapy on the free combination regimen (as recommended) prior to switching. After adjusting for covariates, persons initiating on non‐recommended monotherapy (OR = 2.64, 95% CI 2.47–2.83) or FDCs of two or more antihypertensives (OR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.30–1.55), were more likely to discontinue all antihypertensive drug treatment in the first year compared to persons initiating on recommended monotherapy.

Conclusion

More than half of antihypertensive initiators conformed to Australian guidelines. Initiation on FDCs and other non‐recommended treatments was associated with lower persistence on antihypertensive therapy in the first year. Long‐term effectiveness and outcomes may be enhanced by initiating with low dose monotherapy.

Keywords: Australia, fixed‐dose combinations, hypertension, pharmacoepidemiology

What is Already known About this Subject

Use of FDCs to treat hypertension has been increasing.

In Australia, there is little evidence about how use of antihypertensives, in particular FDCs, follows guidelines.

While there is evidence that the use of FDCs increases persistence compared to the equivalent free combination, little is known about how initiating on FDCs compares to recommended monotherapy.

What this Study Adds

In Australia the choice of first‐line antihypertensive agent follows guidelines for most individuals.

FDCs are being used outside guideline recommendations and often involve higher doses than monotherapy.

Initiation on an FDC and non‐recommended monotherapy was associated with lower persistence on any antihypertensive therapy in the first year.

Introduction

Worldwide, antihypertensive medications are used by 29% of men and 41% of women 1. Treating hypertension is complex, as patients often require multiple medicines to control their blood pressure 2, 3, 4. Moreover, there are a large number of available antihypertensive agents with differing efficacy, side effects and cost; prescribing physicians must account for these multiple factors, as well as a patient's comorbid conditions and other prescribed medicines, when determining the best line of treatment 5. A large proportion of those initiated on antihypertensive drugs discontinue their medication 6, 7. Thus, a key determinant of real world effectiveness is persistence.

Fixed‐dose combination (FDC) products for the treatment of hypertension consist of a single pill containing the active ingredients of two or three antihypertensives with different mechanisms of action. While they reduce pill burden, the lack of dose flexibility with FDCs can be problematic, and create difficulty with identifying the cause of adverse effects 8, 9. Additionally, while FDCs can reduce out‐of‐pocket costs for patients 10, 11, they often incur higher costs for third‐party payers than the subsidy of the individual components 12.

Many international guidelines 13, 14, 15 suggest that individuals with severe hypertension should initiate on combination therapy. In contrast, Australian guidelines only recommend initiation on a single antihypertensive, adding in a second component, followed by upward titration of doses if blood pressure is not adequately controlled 16. The guidelines additionally recommend that patients be stabilized on both of the individual antihypertensives prior to switching to an FDC. There is support for the use of FDCs as first‐line therapy 17, 18, with those continuing on therapy having better blood pressure control than those initiating with monotherapy 19, 20. While one meta‐analysis did not find a persistence benefit for FDCs compared to free combination therapy 21, more recent observational studies have found that initiation on an FDC is associated with greater persistence 22, 23, 24, 25, but few studies have compared initiation on an FDC to monotherapy. The current literature suggests that initiating on an FDC is associated with greater persistence than diuretic monotherapy, but worse persistence than other types of monotherapy 26, 27, 28.

International and Australian studies report that the use of combination therapy is increasing 17, 29, 30. Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate antihypertensive use in Australia, and how real world use compares to Australian guideline recommendations. Specifically, we focus on three aspects of the guidelines: (1) first‐line therapy; (2) uptake of FDCs; and (3) how deviation from recommendations affects discontinuation in the first year.

Methods

Australian guidelines

The guidelines were published in 2008 and updated in 2010 and include recommendations for diagnosis of hypertension, evaluating patients with hypertension, lifestyle modification and drug treatment 16. We focused on drug treatment guidelines, which recommend initiation on monotherapy with an angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, angiotensin‐II receptor blocker (ARB), calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic (in individuals ≥65 years only); this differs from UK guidelines, which recommend initiation on calcium channel blocker monotherapy in individuals ≥55 years 31. The guidelines also provide specific advice for individuals with comorbid or associated conditions. Australian guidelines do not recommend initiation on an FDC, in contrast to North American guidelines that recommend their use as first‐line therapy in certain individuals 13, 14. The recommendations remained consistent during the entire study period.

Data source and study population

In Australia, all citizens and permanent residents are entitled to subsidized access to prescribed medicines through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). We used PBS dispensing records from 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2014 for a 10% random sample of persons dispensed a PBS‐listed medicine. This is a standard dataset provided by the Department of Human Services for analytical use and is selected based on the last digit of each individual's randomly assigned unique identifier. This dataset captures all dispensed PBS‐listed medicines attracting a government subsidy, which occurs when the price of the medicine is above the PBS co‐payment threshold. While many commonly dispensed antihypertensives fall below the general co‐payment and would not be captured in the data, certain individuals (‘concessional beneficiaries’) are eligible for a reduced co‐payment. This population consists primarily of individuals ≥65 years and/or with low incomes and represent the majority of individuals prescribed antihypertensives. We included only long‐term concessional beneficiaries (e.g. individuals dispensed only medicines attracting a reduced co‐payment during the entire study period), as we would have complete capture of dispensed medicines in this population for the entire study period. Individuals had to have at least one dispensing record for any medicine during the run‐in period prior to initiation. To protect the privacy of persons in this dataset, all dates of dispensing are offset randomly by +14 or −14 days; the direction of the offset is the same for all records for each individual.

Our cohort consisted of all persons initiating antihypertensives. As it is common for people to reinitiate on antihypertensives after periods of non‐use, and prior antihypertensive therapy is likely to influence subsequent treatment, to ensure that the cohort consisted primarily of persons naïve to antihypertensives, we used a three‐year run‐in period without evidence of a dispensing for an antihypertensive to define incident use.

Antihypertensive medicines

We classified medicines using the WHO's Anatomic Therapeutic Classification and included all individual and combination medicines listed on the PBS with a primary indication for the treatment of arterial hypertension, including: C03 – Diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, indapamide), C07 – Beta‐blockers (oxprenolol, atenolol, metoprolol tartrate, labetalol), C08 – Calcium channel blockers (felodipine, amlodipine, nifedipine, lercanidipine, verapamil, diltiazem) and C09 – Agents acting on the renin‐angiotensin system (ramipril, enalapril, perindopril, captopril, fosinopril, quinapril, trandolapril, lisinopril, valsartan, eprosartan, candesartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, losartan). We excluded C02 (antihypertensives) as medicines in this class are more commonly used to treat conditions other than hypertension in Australia. The PBS‐listed FDCs of two or more antihypertensives include: an ACE inhibitor/ARB combined with a diuretic (fosinopril/hydrochlorothiazide, candesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, perindopril/hydrochlorothiazide, quinapril/hydrochlorothiazide, eprosartan/ hydrochlorothiazide, telmisartan/hydrochlorothiazide, irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide); an ACE inhibitor/ARB combined with a calcium channel blocker (ramipril/felodipine, trandolapril/verapamil, lercanidipine/enalapril, perindopril/amlodipine); and an ARB combined with a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic (valsartan/amlodipine/hydrochlorothiazide, olmesartan/amlodipine/hydrochlorothiazide). We also included FDCs of an antihypertensive and a medicine where the primary indication was not hypertension, specifically hydrochlorothiazide combined with a potassium‐sparing diuretic (amiloride, triamterene) and amlodipine combined with atorvastatin. All antihypertensives dispensed within the first seven days of initiation were considered to be part of the first‐line therapy.

To determine whether prescribing of first‐line therapy adhered to the guidelines, we classified antihypertensives into the following groups: ACE inhibitors, ARBs, thiazide diuretics (including thiazide‐like diuretics), beta‐blockers and calcium channel blockers. To describe the first year of treatment, we further classified first‐line treatment into: ACE inhibitor/ARB monotherapy, thiazide diuretic monotherapy, beta‐blocker monotherapy, calcium channel blocker monotherapy, antihypertensive FDC only, other FDC only and multiple antihypertensive medicines.

Measures

We identified individuals dispensed medicines for the treatment of several health conditions the year prior to initiation, including those for which there were recommended prescribing practices in the guidelines: angina (C01DA – organic nitrates), depression (N06A – depression, excluding lithium), diabetes (A10 – drugs used in diabetes), gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) (A02BC – proton pump inhibitors), gout (M04 – antigout preparations), heart failure (spironolactone, eplerenone, frusemide, digoxin, ethacrynic acid, carvedilol, bisoprolol, metoprolol succinate), hyperlipidaemia (C10 – lipid modifying agents), and obstructive airway disease (R03 – drugs for obstructive airway disease).

Given the absence of daily dose information, we assumed that individuals were taking one or two tablets per day, in accordance with recommendations for each specific medicine, to determine total days’ supply. We defined discontinuation as a period of 60 days or more past the last day of use (as defined by total days’ supply) without any dispensing. We identified individuals who were still using the same antihypertensive(s) that they initiated on at the end of the first year, without discontinuing, switching to a different antihypertensive or adding another antihypertensive during the entire year. We also calculated the dose for each medicine at initiation.

We identified all individuals who were ever dispensed an antihypertensive FDC in the first year of treatment, calculated the time to initiation, and determined whether they had been dispensed either of the individual medicines, or medicines from the same class(es), prior to initiation.

Statistical analysis

Using logistic regression, we determined the predictors of initiating on each class of antihypertensives (in comparison to all other antihypertensive classes), and predictors of discontinuation in the first year. All models were adjusted for year of initiation, sex, age at initiation, the number of medicines dispensed in the year prior to initiation, and having been dispensed medicines for the management of angina, depression, diabetes, GORD, gout, heart failure, hyperlipidaemia and/or obstructive airway disease. The discontinuation model also included measures of concordance with Australian guidelines. Individuals who initiated on FDCs other than a combination of two antihypertensives were excluded from this model. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata version 12 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics and data access approval

This study has ethics approval from the New South Wales Population and Health Services Ethics committee (2013/11/494). Data access was approved by the Australian Department of Human Services External Request Evaluation Committee.

Results

Choice of first‐line therapy

Over the study period, 55 937 people initiated antihypertensive therapy. The median age was 67 years (interquartile range (IQR), 54–75), and 56.6% were female (Table 1). ACE inhibitors (39.1%) followed by ARBs (29.9%) were the most common antihypertensive classes initiated. Initiation of therapy using a thiazide diuretic (9.9%) was least common. The majority of people dispensed ACE inhibitors (88.0%) and ARBs (85.0%) initiated on monotherapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of antihypertensive initiators [n (%)] by choice of first‐line therapy

| ACE inhibitors (n = 21 862) | ARBs (n = 16 710) | Thiazide diuretics (n = 5548) | Beta‐blockers (n = 9479) | Calcium channel blockers (n = 8085) | Total (n = 55 937) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 18–49 years | 3553 (16.3) | 3001 (18.0) | 1322 (23.8) | 2143 (22.6) | 1708 (21.1) | 10 531 (18.8) |

| 50–59 years | 2969 (13.6) | 2550 (15.3) | 785 (14.2) | 1049 (11.1) | 1018 (12.6) | 7470 (13.4) |

| 60–69 years | 5857 (26.8) | 4968 (29.7) | 1379 (24.9) | 2156 (22.8) | 2037 (25.2) | 14 869 (26.6) |

| 70–79 years | 6316 (28.9) | 4523 (27.1) | 1409 (25.4) | 2585 (27.3) | 2226 (27.5) | 15 635 (28.0) |

| 80+ years | 3167 (14.5) | 1668 (10.0) | 653 (11.8) | 1546 (16.3) | 1096 (13.6) | 7432 (13.3) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 10 414 (47.6) | 7192 (43.0) | 1908 (34.4) | 4142 (43.7) | 3406 (42.1) | 24 276 (43.4) |

| Female | 11 448 (52.4) | 9518 (57.0) | 3640 (65.6) | 5337 (56.3) | 4679 (57.9) | 31 661 (56.6) |

| Number of medicines dispensed in year prior | ||||||

| Quartile 1 (1–2) | 5669 (25.9) | 4736 (28.3) | 1361 (24.5) | 2212 (23.3) | 2033 (25.2) | 14 324 (25.6) |

| Quartile 2 (3–4) | 5082 (23.3) | 3954 (23.7) | 1165 (21.0) | 2115 (22.3) | 1751 (21.7) | 12 749 (22.8) |

| Quartile 3 (5–7) | 5370 (24.6) | 3984 (23.8) | 1375 (24.8) | 2363 (24.9) | 1878 (23.2) | 13 664 (24.4) |

| Quartile 4 (≥8) | 5741 (26.3) | 4036 (24.2) | 1647 (29.7) | 2789 (29.4) | 2423 (30.0) | 15 200 (27.2) |

| Medicines dispensed for treatment of | ||||||

| Angina | 814 (3.7)* | 230 (1.4) | 66 (1.2) | 685 (7.2)* | 332 (4.1)* | 1941 (3.5) |

| Depression | 4935 (22.6) | 3656 (21.9) | 1375 (24.8) | 2400 (25.3) | 1951 (24.1) | 13 091 (23.4) |

| Diabetes | 3059 (14.0)* | 1500 (9.0) | 338 (6.1) | 564 (6.0) | 559 (6.9) | 5514 (9.9) |

| Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease | 6515 (29.8) | 4746 (28.4) | 1671 (30.1) | 3040 (32.1) | 2546 (31.5) | 16 891 (30.2) |

| Gout | 803 (3.7) | 620 (3.7) | 145 (2.6) | 307 (3.2) | 242 (3.0) | 1928 (3.5) |

| Heart failure | 1626 (7.4)* | 662 (4.0) | 379 (6.8) | 741 (7.8)* | 451 (5.6) | 3537 (6.3) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 6720 (30.7) | 4493 (26.9) | 1304 (23.5) | 2674 (28.2) | 2092 (25.9) | 15 788 (28.2) |

| Obstructive airway disease | 4225 (19.3) | 3202 (19.2) | 1237 (22.3) | 1575 (16.6) | 1897 (23.5) | 11 011 (19.7) |

| Initiated as part of fixed‐dose combination | ||||||

| Antihypertensives combination | 1136 (5.2) | 2077 (12.4) | 2405 (43.3) | 0 (0.0) | 867 (10.7) | 3205 (5.7) |

| Other combination† | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1307 (23.6) | 0 (0.0) | 681 (8.4) | 1988 (3.5) |

| Initiated in free combination with another antihypertensive | ||||||

| 1523 (7.0) | 483 (3.0) | 126 (2.3) | 1403 (14.8) | 963 (11.9) | 2434 (4.3) | |

Individuals can appear in more than one column if initiated on multiple antihypertensives.

Possibly dispensed for indication other than hypertension.

Other combinations include hydrochlorothiazide and a potassium‐sparing diuretic, and amlodipine and atorvastatin.

Five per cent (n = 2804) of individuals initiated on an antihypertensive FDC, most commonly an ACE inhibitor/ARB in combination with a diuretic (71.4%), followed by an ACE inhibitor/ARB in combination with a calcium channel blocker (26.8%), and a triple combination of an ARB, a calcium channel blocker and a thiazide diuretic (1.9%), while 4.3% (n = 2434) initiated on multiple medicines.

Consistent with the guidelines, in our multivariable analysis persons dispensed diabetes medicines were more likely to be dispensed ACE inhibitors (OR = 2.15, 95% CI 2.02–2.28) but less likely to be dispensed thiazide diuretics (OR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.48–0.62) (Table S1). Beta‐blockers were less commonly used in persons dispensed medicines for diabetes (OR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.43–0.52) and obstructive airway disease (OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.62–0.71), but more common in persons dispensed medicines to treat angina (OR = 2.54, 95% CI 2.29–2.82) and depression (OR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.00–1.12); the latter combination is considered potentially harmful in the guidelines. Other potentially harmful/beneficial practices are indicated in Table S1.

Overall, 58.1% (n = 32 469) of initiators had no observed deviations from Australian guidelines. The most common deviations were not initiating on monotherapy with an ACE inhibitor, ARB, calcium channel blocker or thiazide diuretic (≥65 years only) (26.3%), and not initiating on the lowest recommended dose (30.6%) (Table 2). Persons who initiated on non‐recommended therapies (i.e. non‐recommended monotherapy, an FDC or multiple medicines) tended to be younger and also were more likely to initiate on higher doses and a “potentially harmful” comorbidity‐antihypertensive combination (Table 3).

Table 2.

Number and percentage of initiators according to Australian recommendations

| Australian recommendations | n (Total) | n (%) following recommendation | n (%) not following recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| For patients with uncomplicated hypertension, begin antihypertensive monotherapy with an ACEI inhibitor/ARB, a calcium channel blocker, or a thiazide diuretic (≥65 years only). Beta‐blockers are not recommended in uncomplicated hypertension. | 55 937 | 41 226 (73.7) | 14 711 (26.3) |

| Begin antihypertensive therapy with the lowest recommended dose | 55 937 | 38 813 (69.4) | 17 124 (30.6) |

| For patients with comorbid and associated conditions: The following antihypertensive agents are considered potentially beneficial: | |||

| Angina and beta‐blockers (except oxprenolol, pindolol), calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors | 1943 | 1689 (86.9) | 254 (13.1) |

| Gout and losartan | 1928 | 2 (0.1) | 1926 (99.9) |

| Heart failure and ACE inhibitors, ARBs, thiazide diuretics, beta‐blockers | 3537 | 3152 (89.1) | 385 (10.9) |

| Diabetes and ACE inhibitors, ARBs | 5514 | 4539 (82.3) | 975 (17.7) |

| The following antihypertensive agents are considered potentially harmful: | |||

| Asthma/COPD and beta‐blockers | 11 011 | 9437 (85.7) | 1574 (14.3) |

| Depression and beta‐blockers | 13 091 | 10 691 (81.7) | 2400 (18.3) |

| Gout and thiazide diuretics | 1928 | 1783 (92.5) | 145 (7.5) |

| Heart failure and calcium channel blockers | 3537 | 3086 (87.2) | 451 (12.8) |

| Diabetes and beta‐blockers, thiazide diuretics | 5514 | 4621 (83.8) | 893 (16.2) |

| For patients who were dispensed a fixed‐dose antihypertensive combination: | |||

| Patients should be established on the free combination regimen before switching to a FDC product | 6399 | 108 (1.7) | 6291 (98.3) |

Table 3.

Characteristics of antihypertensive initiators [n (%)] by concordance with guidelines

| Recommended monotherapy | Not recommended therapies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy | Fixed‐dose combination | Multiple medicines | ||

| Age | ||||

| 18–49 years | 6819 (16.5) | 2126 (28.0) | 629 (22.5) | 434 (17.8) |

| 50–59 years | 5416 (13.1) | 962 (12.7) | 503 (18.0) | 315 (13.0) |

| 60–69 years | 11 292 (27.4) | 1714 (22.6) | 787 (28.2) | 610 (25.1) |

| 70–79 years | 12 003 (29.1) | 1836 (24.2) | 646 (23.2) | 674 (27.7) |

| 80+ years | 5694 (13.8) | 948 (12.5) | 226 (8.1) | 400 (16.4) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 18 180 (44.1) | 2983 (39.3) | 1295 (46.4) | 1243 (51.1) |

| Female | 23 044 (55.9) | 4603 (60.7) | 1496 (53.6) | 1190 (48.9) |

| Number of medicines dispensed in year prior | ||||

| Quartile 1 (1–2) | 10 491 (25.5) | 1909 (25.2) | 827 (29.6) | 687 (28.2) |

| Quartile 2 (3–4) | 9375 (22.7) | 1754 (23.1) | 635 (22.8) | 560 (23.0) |

| Quartile 3 (5–7) | 10 085 (24.5) | 1902 (25.1) | 666 (23.9) | 541 (22.2) |

| Quartile 4 (≥8) | 11 273 (27.4) | 2021 (26.6) | 663 (23.8) | 645 (26.5) |

| Medicines dispensed for treatment of: | ||||

| Angina | 1733 (4.2) | 3 (0.0) | 22 (0.8) | 155 (6.4) |

| Depression | 9378 (22.8) | 2063 (27.2) | 614 (22.0) | 510 (21.0) |

| Diabetes | 4556 (11.1) | 373 (4.9) | 228 (8.2) | 222 (9.1) |

| Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease | 12 577 (30.5) | 2271 (29.9) | 759 (27.2) | 724 (29.8) |

| Gout | 1508 (3.7) | 212 (2.8) | 91 (3.3) | 80 (3.3) |

| Heart failure | 3091 (7.5) | 37 (0.5) | 138 (4.9) | 162 (6.7) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 11 985 (29.1) | 1867 (24.6) | 700 (25.1) | 665 (27.3) |

| Obstructive airway disease | 9378 (22.8) | 2063 (27.2) | 614 (22.0) | 510 (21.0) |

| Initiated on lowest recommended dose | 32 938 (79.9) | 3479 (45.9) | 1289 (46.2) | 494 (20.3) |

| Initiating on a ‘potentially harmful’ comorbidity‐antihypertensive combination | 952 (2.3) | 2776 (36.6) | 235 (8.4) | 624 (25.7) |

| Year of initiation | ||||

| 2008/09 | 8488 (20.6) | 1393 (18.4) | 529 (19.0) | 562 (23.1) |

| 2009/10 | 7167 (17.4) | 1294 (17.1) | 455 (16.3) | 458 (18.8) |

| 2010/11 | 6802 (16.5) | 1299 (17.1) | 453 (16.2) | 380 (15.6) |

| 2011/12 | 6518 (16.5) | 1121 (14.8) | 437 (15.7) | 318 (13.1) |

| 2012/13 | 6239 (15.1) | 1289 (17.0) | 438 (15.7) | 323 (13.3) |

| 2013/14 | 6010 (14.6) | 1190 (15.7) | 479 (17.2) | 392 (16.1) |

Uptake of antihypertensive FDCs

Among persons with at least one year of follow‐up (n = 45 954), 13.9% (n = 6399) were dispensed an antihypertensive FDC within the first year. Of these, 40.4% were dispensed the FDC as their first antihypertensive, and a further 25.9% switched to the FDC within the first 90 days. Prior to the FDC, only 1.7% were dispensed both of the medicines in the combination product. A total of 47.5% of persons were dispensed at least one of the individual medicines, while 55.9% were dispensed at least one of the individual medicine classes. Moreover, switching to the FDC resulted in a dose increase for 48.4% of persons who had been dispensed one of the individual medicines prior to the FDC.

Discontinuation

Overall, 33.2% (n = 15 260) of persons were still being dispensed the same antihypertensive(s) they initiated on, without discontinuation, switching or addition of another antihypertensive at the end of the first year. Continuing use of the same initial therapy was highest among those who initiated on ACE inhibitor/ARB monotherapy (40.9%) and lowest among those who initiated on multiple medicines (13.5%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Use of antihypertensives in first year after initiation [n (%)] by first‐line therapy in individuals with one year of follow‐up (n = 45 954)

| Monotherapy | FDC only | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitor/ARB (n = 27 632) | Thiazide diuretic (n = 1486) | Beta‐blockers (n = 6478) | Calcium channel blocker (n = 4538) | Antihypertensive combination (n = 2266) | Other combination* (n = 1626) | Multiple medicines (n = 1928) | Total (n = 45 954) | |

| Discontinuation of all antihypertensive therapy | ||||||||

| After first dispensing | 4334 (15.7) | 676 (45.5) | 2625 (40.5) | 1371 (30.2) | 636 (28.1) | 826 (50.8) | 376 (19.5) | 10 844 (23.6) |

| At any time | 10 354 (37.5) | 967 (65.1) | 4482 (69.2) | 2562 (56.5) | 1243 (54.9) | 1131 (69.6) | 860 (44.6) | 21 599 (47.0) |

| Continuous antihypertensive therapy | ||||||||

| No change in therapy from initiation | 11 289 (40.9) | 287 (19.3) | 1213 (18.7) | 1192 (26.3) | 662 (29.2) | 357 (22.0) | 261 (13.5) | 15 260 (33.2) |

| Switching to or addition of another antihypertensive(s) | 5989 (21.7) | 232 (15.6) | 783 (12.1) | 784 (17.3) | 361 (15.9) | 138 (8.5) | 809 (42.0) | 9096 (19.8) |

| Uptake of antihypertensive fixed‐dose combination | ||||||||

| 3146 (11.4) | 114 (7.7) | 144 (2.2) | 256 (5.6) | 2266 (100.0) | 38 (2.3) | 435 (22.5) | 6399 (13.9) | |

Other combinations include hydrochlorothiazide and a potassium‐sparing diuretic, and amlodipine and atorvastatin.

Forty‐seven per cent (n = 21 599) of individuals discontinued all antihypertensive treatment in the first year, including 23.6% who had only one antihypertensive dispensing (or one co‐dispensing for those initiated on multiple medicines). Initiation on ACE inhibitor/ARB monotherapy was associated with the lowest rate of discontinuation of all treatment (37.5%), while over half of individuals who initiated on all other monotherapies as well as an FDC discontinued their use (Table 4).

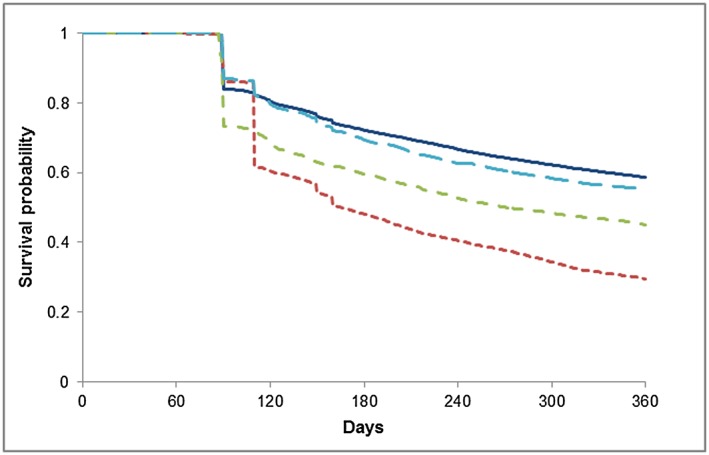

Time to discontinuing first‐line therapy according to adherence to guidelines is shown in Figure 1. In our multivariable analysis, compared to individuals who initiated on the recommended monotherapy, those who initiated on the non‐recommended monotherapy (i.e. beta‐blockers and thiazide diuretics in individuals <65 years) were more likely to change from the treatment they initiated on (OR = 2.01, 95% CI 1.86–2.17) (Table 5) and discontinue all treatment (OR = 2.64, 95% CI 2.47–2.83) (Table 5). Individuals who initiated on an antihypertensive FDC were also more likely to change from their initial treatment (OR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.09–1.32) as well as discontinue all antihypertensive treatment (OR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.30–1.55).

Figure 1.

Time to discontinuation by first‐line therapy and adherence to Australian guidelines.  Monotherapy (recommended),

Monotherapy (recommended),  Fixed‐dosed combination,

Fixed‐dosed combination,  Monotherapy (not recommended),

Monotherapy (not recommended),  Multiple Medicines

Multiple Medicines

Table 5.

Logistic regression of discontinuation among 45 954 initiators with at least one year of follow‐up

| Discontinuation of initial therapy | Discontinuation of all antihypertensive therapy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P‐value | OR (95% CI) | P‐value | OR (95% CI) | P‐value | OR (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| First‐line therapy | ||||||||

| Monotherapy (recommended) | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 |

| Monotherapy (not recommended)† | 2.71 (2.54–2.91) | 2.01 (1.86–2.17) | 3.37 (3.18–3.58) | 2.64 (2.47–2.83) | ||||

| Fixed‐dose combination (antihypertensives) | 1.48 (1.34–1.62) | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | 1.73 (1.59–1.88) | 1.42 (1.30–1.55) | ||||

| Multiple antihypertensives | 3.90 (3.42–4.46) | 2.70 (2.36–3.10) | 1.15 (1.04–1.26) | 0.81 (0.73–0.89) | ||||

| Not initiating on lowest recommended dose * | 2.15 (2.05–2.26) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.61–1.79) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.85–2.01) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.55–1.70) | <0.001 |

| Initiating on a “potentially harmful” comorbidity‐antihypertensive combination | 2.27 (2.08–2.47) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.14–1.40) | <0.001 | 2.18 (2.03–2.34) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) | 0.006 |

| Year of initiation | ||||||||

| 2008/09 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.18 | 1.01 (0.94–1.07) | 0.37 | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 0.04 | 0.99 (0.94–1.06) | 0.19 |

| 2009/10 | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | ||||

| 2010/11 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | ||||

| 2011/12 | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | ||||

| 2012/13 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | ||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–49 years | 2.08 (1.96–2.22) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.77–2.02) | <0.001 | 2.97 (2.80–3.14) | <0.001 | 2.72 (2.56–2.89) | <0.001 |

| 50–59 years | 1.22 (1.15–1.31) | 1.19 (1.11–1.27) | 1.47 (1.38–1.56) | 1.43 (1.34–1.52) | ||||

| 60–69 years | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | ||||

| 70–79 years | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | ||||

| 80+ years | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) | 1.15 (1.08–1.24) | 1.28 (1.20–1.37) | 1.27 (1.18–1.35) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.54 | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.84 | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.37 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | ||||

| Number of medicines dispensed in year prior | ||||||||

| Quartile 1 (1–2) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.009 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 | 1.00 (Ref) | <0.001 |

| Quartile 2 (3–4) | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | ||||

| Quartile 3 (5–7) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | ||||

| Quartile 4 (≥8) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) | ||||

| Medicines dispensed for treatment of: | ||||||||

| Angina | 1.16 (1.03–1.29) | 0.01 | 1.27 (1.13–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.93–1.15) | 0.52 | 1.25 (1.13–1.40) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 0.10 | 0.91 (0.87–0.96) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.90–0.99) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 0.81 (0.76–0.87) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.82–0.94) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.86–0.97) | 0.006 | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | 0.49 |

| Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease | 0.97 (0.92–1.01) | 0.10 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.89 | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.11 |

| Gout | 0.85 (0.77–0.95) | 0.003 | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.83 (0.74–0.92) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.007 |

| Heart failure | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) | 0.02 | 0.93 (0.85–1.00) | 0.06 | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 0.18 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.75 (0.72–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.71–0.77) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive airway disease | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.51 | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.80 | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 0.32 | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 0.66 |

Adjusted for all variables in the table.

Beta‐blockers without any indication for their use, or thiazide diuretics in <65 years.

While persons initiating on multiple antihypertensives were more likely to change from their initial treatment, they were less likely to discontinue all antihypertensive treatment (OR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.73–0.89) (Table 5). Initiating on greater than the lowest recommended dose was also associated with a greater risk of discontinuing all treatment (OR = 1.62, 95% CI 1.55–1.70).

Discussion

This is one of the few population‐based studies of antihypertensive initiation in Australia. When compared to Australian guidelines, we observed deviations from recommendations for first‐line therapy in 42% of individuals who initiated antihypertensive treatment. Contrary to recommendations, over half of people dispensed an FDC were not previously dispensed either of the medicines that formed part of the FDC. We also observed high rates of treatment discontinuation in the first year, which was greater in individuals initiating on the non‐recommended monotherapy, FDCs or a higher than recommended dose.

The main strength of this study is that it is population‐based and has complete capture of dispensing for our population. We also used a long run‐in period to reduce the misclassification of incident users. Given that prolonged periods of discontinuation are common in persons treated with antihypertensives 32, this approach ensures that the choice of first‐line therapy was not influenced by previous treatment; it is in these treatment‐naïve patients that following recommendations is most important. The main limitation of our study is the lack of diagnostic information. We have assumed that the individuals in our sample were dispensed antihypertensives for the treatment of hypertension, but for some individuals they may have been dispensed for other indications, particularly beta‐blockers which are used to treat various cardiac conditions other than hypertension. Our data also lack clinical information that would allow us to determine the appropriateness of prescribing by identifying individuals with severe hypertension and relevant comorbidities. Further, the differences observed between choices of therapy may reflect underlying differences between the treatment populations beyond the factors for which we adjusted.

Our finding of high rates of discontinuation, particularly after the first dispensing, is similar to a Canadian study (1994–2002) that found that 50% discontinued in the first year and 20% discontinued after the first fill 6 and a German study (2000–2001) that found that 16% received only one prescription 7. We also found that initiating on a higher dose and a potentially harmful comorbidity‐antihypertensive combination, both of which increase the risk of adverse effects, was associated with increased discontinuation of all drug therapy, as was a younger age, male sex and an increased pill burden. Interestingly, initiating on multiple medicines was associated with an increased risk of discontinuing all therapy, but a decreased risk after adjusting for dose, suggesting that the greater risk for patients initiating on multiple medicines was attributable to being given higher than recommended doses.

Overall initiation on an FDC in our sample was lower than the findings of a US study (2007–2010) 33, but similar to the figures reported in a Canadian study (1999–2010) 27. This may reflect different national recommendations; during the time period of our study, the American Heart Association 34, and the Seventh Joint National Committee (JNC) 35 both recommended initiation with combination therapy for individuals with severe hypertension, while in Australia initiation with an FDC is not recommended. Few studies have compared persistence in initiators of an FDC to monotherapy; similar to our findings, an observational study from Canada found that persistence on therapy was lower among individuals who initiated on an FDC compared to ACE inhibitor, ARB or calcium channel blocker monotherapy, the main recommended first‐line therapies in Australia 27.

While for most individuals the choice of first‐line antihypertensive is consistent with current recommendations, we have found that FDCs are being used outside Australian guidelines and that this practice is reducing long‐term treatment persistence. Initiating on FDCs without prior therapy has been associated with greater discontinuation 36. These findings are concerning as more and more FDCs are being introduced to the market. Treatment for hypertension is often life‐long, and adherence and persistence to antihypertensive therapy is generally poor 37. Given that there are currently few effective interventions for improving medication adherence 38, prescribing physicians should engage in treatment strategies that support optimal adherence.

While it is generally argued that FDC might support continuing drug therapy, evidence to support this assertion, and in particular that initiation on FDC will support long‐term therapy and improve health outcomes is largely lacking. Used appropriately, FDCs have a role in individuals who require multiple agents to control their blood pressure, and are an attractive long‐term option due to their reduced cost. However, more research is needed to determine which FDC initiation strategies optimize long‐term persistence. Starting off on the right foot with antihypertensive therapy is essential to achieving maximum potential health benefits.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: AS and SP had support from the National Health and Medical Research Council for the submitted work; AS, SP and NB had no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; AS, SP and NB had no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

This research is supported, in part, by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Medicines and Ageing (ID: 1060407). Sallie‐Anne Pearson is supported by a Cancer Institute New South Wales Career Development Fellowship (ID: 12/CDF/2‐25). Andrea Schaffer is supported by the NHMRC (ID: 1074924). We thank Tracey Laba for her contributions.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study and the interpretation of the data. AS drafted the manuscript; SP and NB revised it critically. All authors gave approval to the final version. Nicholas A. Buckley was the principal investigator.

Supporting information

Table S1 Multivariable analysis of initiation on each antihypertensive class as compared to all other classe

Supporting info item

Schaffer, A. L. , Pearson, S. ‐A. , and Buckley, N. A. (2016) How does prescribing for antihypertensive products stack up against guideline recommendations? An Australian population‐based study (2006–2014). Br J Clin Pharmacol, 82: 1134–1145. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13043.

References

- 1. Pereira M, Lunet N, Azevedo A, Barros H. Differences in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension between developing and developed countries. J Hypertens 2009; 27: 963–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furmaga EM, Cunningham FE, Cushman WC, Dong D, Jiang R, Basile J, et al. National utilization of antihypertensive medications from 2000 to 2006 in the Veterans Health Administration: focus on thiazide diuretics. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008; 10: 770–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheung BM, Wong YL, Lau CP. Queen Mary Utilization of Antihypertensive Drugs Study: use of antihypertensive drug classes in the hypertension clinic 1996–2004. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 60: 90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vincze G, Barner JC, Bohman T, Linn WD, Wilson JP, Johnsrud MT, et al. Use of antihypertensive medications among United States veterans newly diagnosed with hypertension. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 795–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaiser EA, Lotze U, Schafer HH. Increasing complexity: which drug class to choose for treatment of hypertension in the elderly? Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9: 459–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evans CD, Eurich DT, Remillard AJ, Shevchuk YM, Blackburn D. First‐fill medication discontinuations and nonadherence to antihypertensive therapy: an observational study. Am J Hypertens 2012; 25: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasford J, Schroder‐Bernhardi D, Rottenkolber M, Kostev K, Dietlein G. Persistence with antihypertensive treatments: results of a 3‐year follow‐up cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63: 1055–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burnier M. Antihypertensive combination treatment: state of the art. Curr Hypertens Rep 2015; 17: 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Angeli F, Reboldi G, Mazzotta G, Garofoli M, Ramundo E, Poltronieri C, et al. Fixed‐dose combination therapy in hypertension: cons. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2012; 19: 51–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brixner DI, Jackson KC 2nd, Sheng X, Nelson RE, Keskinaslan A. Assessment of adherence, persistence, and costs among valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide retrospective cohorts in free‐ and fixed‐dose combinations. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 2597–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akazawa M, Fukuoka K. Economic impact of switching to fixed‐dose combination therapy for Japanese hypertensive patients: a retrospective cost analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke PM, Avery AB. Evaluating the costs and benefits of using combination therapies. Med J Aust 2014; 200: 518–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison‐Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014; 311: 507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daskalopoulou SS, Rabi DM, Zarnke KB, Dasgupta K, Nerenberg K, Cloutier L, et al. The 2015 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2015; 31: 549–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abdul Rahman AR, Reyes EB, Sritara P, Pancholia A, Van Phuoc D, Tomlinson B. Combination therapy in hypertension: an Asia‐Pacific consensus viewpoint. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31: 865–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Heart Foundation of Australia . Guide to management of hypertension 2008 (Updated December 2010) [online]. Available at https://heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/HypertensionGuidelines2008to2010Update.pdf (last accessed 20 May 2016).

- 17. Byrd JB, Zeng C, Tavel HM, Magid DJ, O'Connor PJ, Margolis KL, et al. Combination therapy as initial treatment for newly diagnosed hypertension. Am Heart J 2011; 162: 340–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neutel JM, Smith DH, Weber MA. Low‐dose combination therapy: an important first‐line treatment in the management of hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2001; 14: 286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Egan BM, Bandyopadhyay D, Shaftman SR, Wagner CS, Zhao Y, Yu‐Isenberg KS. Initial monotherapy and combination therapy and hypertension control the first year. Hypertension 2012; 59: 1124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gradman AH, Parise H, Lefebvre P, Falvey H, Lafeuille MH, Duh MS. Initial combination therapy reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: a matched cohort study. Hypertension 2013; 61: 309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed‐dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta‐analysis. Hypertension 2010; 55: 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baser O, Andrews LM, Wang L, Xie L. Comparison of real‐world adherence, healthcare resource utilization and costs for newly initiated valsartan/amlodipine single‐pill combination versus angiotensin receptor blocker/calcium channel blocker free‐combination therapy. J Med Econ 2011; 14: 576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang W, Chang J, Kahler KH, Fellers T, Orloff J, Wu EQ, et al. Evaluation of compliance and health care utilization in patients treated with single pill vs. free combination antihypertensives. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 2065–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sherrill B, Halpern M, Khan S, Zhang J, Panjabi S. Single‐pill vs. free‐equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta‐analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011; 13: 898–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zeng F, Patel BV, Andrews L, Frech‐Tamas F, Rudolph AE. Adherence and persistence of single‐pill ARB/CCB combination therapy compared to multiple‐pill ARB/CCB regimens. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 2877–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corrao G, Parodi A, Zambon A, Heiman F, Filippi A, Cricelli C, et al. Reduced discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment by two‐drug combination as first step. Evidence from daily life practice. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 1584–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tu K, Anderson LN, Butt DA, Quan H, Hemmelgarn BR, Campbell NR, et al. Hypertension Outcome Surveillance Team. Antihypertensive drug prescribing and persistence among new elderly users: implications for persistence improvement interventions. Can J Cardiol 2014; 30: 647–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel BV, Remigio‐Baker RA, Thiebaud P, Preblick R, Plauschinat C. Improved persistence and adherence to diuretic fixed‐dose combination therapy compared to diuretic monotherapy. BMC Fam Pract 2008; 9: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gadzhanova S, Ilomaki J, Roughead EE. Antihypertensive use before and after initiation of fixed‐dose combination products in Australia: a retrospective study. Int J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 35: 613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gu Q, Paulose‐Ram R, Dillon C, Burt V. Antihypertensive medication use among US adults with hypertension. Circulation 2006; 113: 213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) . Hypertension: The Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults: Update of Clinical Giudelines 18 and 34 (Internet). London: Royal College of Physicians, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Wijk BL, Avorn J, Solomon DH, Klungel OH, Heerdink ER, de Boer A, et al. Rates and determinants of reinitiating antihypertensive therapy after prolonged stoppage: a population‐based study. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 689–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kent ST, Shimbo D, Huang L, Diaz KM, Kilgore ML, Oparil S, et al. Antihypertensive medication classes used among Medicare beneficiaries initiating treatment in 2007–2010. PLoS One 2014; 9: e105888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension 2014; 63: 878–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289: 2560–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simons LA, Ortiz M, Calcino G. Persistence with a single pill versus two pills of amlodipine and atorvastatin: the Australian experience, 2006–2010. Med J Aust 2011; 195: 134–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kronish IM, Woodward M, Sergie Z, Ogedegbe G, Falzon L, Mann DM. Meta‐analysis: impact of drug class on adherence to antihypertensives. Circulation 2011; 123: 1611–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 11: CD000011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Multivariable analysis of initiation on each antihypertensive class as compared to all other classe

Supporting info item