Abstract

Objective

In children with traumatic brain injury (TBI), 1) to describe the hospital discharge functional outcome and change from baseline function using the Functional Status Scale (FSS) and 2) to determine any associations between discharge FSS and age, injury mechanism, neurologic exam, imaging, and other predictors of outcome.

Design

Prospective observational cohort study, May 2013 to November 2015.

Setting

Two U.S. children's hospitals designated as American College of Surgeons level 1 Pediatric Trauma Centers.

Patients

Children < 18 years old admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) with acute TBI and either a surgical or critical care intervention within the first 24 hours or in-hospital mortality.

Interventions

None

Measurements and Main Results

The primary outcome was hospital discharge FSS. Most, 133/196 (68%), had severe TBI (admission GCS 3–8). Overall hospital mortality was 14%; 20% among those with severe TBI. Hospital discharge FSS had an inverse relationship with GCS: for each increase in admission GCS by 1, the discharge FSS decreased by 0.5 (95% CI: 0.7 to 0.3). Baseline FSS was collected at one site, N = 75. At that site, nearly all (61/62) of the survivors had normal or near-normal (≤ 7) pre-injury FSS. More than one-third, 23/62 (37%), of survivors had new morbidity at hospital discharge (increase in FSS ≥ 3). Among children with severe TBI who had baseline FSS collected, 21/41 (51%) of survivors had new morbidity at hospital discharge. The mean change in FSS from baseline to hospital discharge was 3.9 ± 4.9 overall and 5.2 ± 5.4 in children with severe TBI.

Conclusions

More than one-third of survivors, and approximately half of survivors with severe TBI, will have new morbidity. Hospital discharge FSS, change from baseline FSS, and new morbidity acquisition can be used as outcome measures for hospital-based care process improvement initiatives and interventional studies of children with TBI.

Keywords: pediatrics, craniocerebral trauma, brain injuries, patient outcome assessment, critical care outcomes

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) causes approximately 2,200 deaths and 35,000 hospitalizations in U.S. children annually.(1) Children who survive TBI frequently have new morbidities such as motor, communication, behavioral, or social impairments.(2) Trials of acute interventions for children with TBI are hampered by a lack of relevant, easily administered functional outcome measures that can be used at the time of intensive care unit (ICU) or hospital discharge. Easily administered instruments such as the Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) and the Pediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC) lack the sensitivity and precision required for studies of interventions.(3–6) Other instruments such as the Glasgow Outcome Scale - Extended, Pediatric version (GOS-E Peds)(7) and the King's Outcome Scale for Childhood Head Injury (KOSCHI)(8) are focused on patient function after return to home and community.

Improvements in the care of critically ill children have decreased ICU mortality to less than 5%, but survivors often have significant functional impairment.(9–13) In response to the need for a reliable, rapid measure of functional outcome appropriate for in-hospital use, the NIH-funded Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN)(14) developed and validated the Functional Status Scale (FSS).(15, 16)

The FSS has 6 domains: Mental, Sensory, Communication, Motor, Feeding, and Respiratory. The scale in each domain is from 1 (no dysfunction) to 5 (very severe dysfunction), with a total score from 6 (normal) to 30 (very severe dysfunction in all domains). Appendix Table 1 shows the 6 domains and the 5 levels within each domain. The FSS is designed to be collected from hospital providers (e.g., a patient's primary nurse), supplemented by medical records when necessary.(17) The FSS correlates with a gold-standard adaptive behavior instrument, the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS II), with a Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.60. It also discriminates moderate and severe decrements in adaptive behavior well (areas under the curve 0.82 and 0.86, respectively).(15) Interrater reliability is excellent: the intraclass correlation coefficient is 0.95 for the six domain scores.(15) Importantly, Pollack et al. have validated that a FSS score at hospital discharge ≥ 3 points above a child's pre-hospitalization baseline represents newly impaired functional status or "new morbidity" in survivors of critical illness or injury.(12)

However, the studies of the FSS to date have analyzed heterogeneous cohorts of critically ill children, and no study of children with TBI to date has reported FSS scores. The distributions of hospital discharge FSS and change in FSS from baseline to hospital discharge in critically injured children with TBI are unknown. We conducted this multi-center prospective observational study to accomplish the following aims: 1) to describe FSS and change in FSS from baseline in children admitted to an ICU after TBI and 2) to determine any associations between discharge FSS and age, injury mechanism, neurologic exam findings, brain computed tomography (CT) findings, and other predictors of outcome in children with TBI.(18–21)

Methods

Study Sites and Subject Enrollment

This prospective cohort study was conducted at two American College of Surgeons (ACS) freestanding level I Pediatric Trauma Centers: Primary Children's Hospital (PCH) in Salt Lake City, UT and Children's Hospital Colorado (CHCO) in Aurora, CO. Each site has between 2000 and 3000 Pediatric ICU admissions per year. At PCH, we enrolled patients from May, 2013 to September, 2015. At CHCO, we enrolled patients from September, 2014 to November, 2015. We reviewed the ICU census at each site daily, checked ICU admission logbooks at PCH, and reviewed ICU screening logs at CHCO to ensure that no eligible child was missed. Because the study was granted a waiver of consent at both sites (see Regulatory Approvals below), all eligible patients were enrolled.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We prospectively identified all patients < 18 years old admitted to an ICU with a diagnosis of acute TBI and either a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ≤ 12 or a neurosurgical procedure (intracranial pressure [ICP] monitor, external ventricular drain [EVD], craniotomy, or craniectomy) within the first 24 hours of admission. We excluded surviving patients discharged from the ICU within 24 hours of ICU admission without an intervention (invasive or noninvasive ventilation, ICP monitoring, any operative procedure, an arterial or central venous catheter, or osmolar therapy). We categorized TBI severity using the ED GCS: 3–8 = severe, 9–12 = moderate, 13–15 = mild. For the 10 patients who did not have a GCS measured in the ED (direct admissions to the ICU), we used the GCS measured on ICU admission. Children with mild TBI who did not receive a neurosurgical procedure in the first 24 hours were excluded.

Prospective Data Collection

A study team member (RD, CK, or TB at PCH; DL, YS, or TB at CHCO) prospectively collected clinical data through regular review of paper and electronic documentation and discussions with providers as needed. Data were entered directly into secure electronic data capture platforms designed for clinical research: OpenClinica™ at PCH and Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)(22) at CHCO.

For variables such as GCS that might be documented by multiple providers or in multiple locations in the medical record, we defined a hierarchy of data sources. In the Emergency Department (ED), we used the following data sources in order of priority: Trauma Surgery attending physician note, then Neurosurgery attending physician note, then ED attending physician note. Similarly, in the ICU we used the ICU attending physician note, then ICU advanced practice provider note, then ICU resident note, then ICU nursing flowsheet. At the time of each GCS assessment, the study team recorded whether the patient was intubated, sedated, chemically paralyzed, or had obstruction to eye assessment.(23)

We captured the time and text report of the first brain CT study formally read by a PCH or CHCO pediatric radiologist. The presence or absence of CT features (e.g. subdural hematoma [SDH]) were extracted from the CT report by the study team.

Functional Status Scale Collection

The FSS was collected on patients with TBI at PCH beginning in May 2013. All FSS scoring was conducted by study team or Trauma team members trained in its use. At PCH, transfer to inpatient rehabilitation is a formal discharge and readmission to the hospital. For those patients who received inpatient rehabilitation, the FSS was obtained on the day of that discharge/readmission.

Baseline FSS was only collected at CHCO. The study team at CHCO collected the baseline FSS from the admission medical documentation as the group that developed the FSS has done in two previous studies.(16, 17) The study team collected the discharge FSS from hospital providers (primary nurses, most often) on the day of discharge. We did not collect the time spent obtaining each FSS score, but the CHCO coordinators plan for the conversation with a patient's provider to take approximately 2 minutes. At CHCO, inpatient rehabilitation begins as a transfer of primary service. To align the "discharge day" at the two sites, for those patients who received inpatient rehabilitation at CHCO the FSS was collected on the day of transfer to rehabilitation.

We categorized FSS scores using the rubric developed by Pollack et al.(12) That 5-category rubric is designed to follow the categories of the PCPC/POPC system, but has greater granularity within each category.(4, 16)

Statistical Methods

Means are shown ± standard deviation (SD). Medians are shown with interquartile range (IQR). We tested two-sample differences in FSS using Student's t-test assuming unequal variances. To estimate variation of FSS scores within categories of admission GCS, we used the approach of Pollack et al. and calculated the width ("dispersion") of the 10th to 90th percentile range.(12) To test the FSS-age, FSS-mechanism, and FSS-GCS relationships, we fit three separate linear regression models. Age (in years) and GCS were fit as continuous variables and injury mechanism as a categorical variable. Scatterplots are shown as "bubble charts." The area of each point is directly proportional to the number of patients with that particular combination of X and Y values.(24) We grouped IVH and SAH to be consistent with the Rotterdam CT scoring system(18, 20)

Data analysis was conducted in R version 3.3.0.(25) We defined statistical significance as P < 0.05. Code to generate the analysis and the manuscript was written using rmarkdown(26), compiled using knitr(27), and is entirely reproducible. The figures were generated using the ggplot2(28) package.

Regulatory Approvals

This study was granted a waiver of consent by the institutional review boards at both institutions.

Results

Prospective Cohort

We enrolled 196 consecutive patients overall, 121 (62%) at PCH and 75 (38%) at CHCO (Table 1). Nearly one-quarter of the patients were injured by known or suspected child abuse. The "Other" injury mechanism category included injuries related to penetrating projectiles, all-terrain vehicles, horseback riding, and others. At the time of GCS assessment, 134/196 (68%) were intubated, 118/196 (60%) were under the influence of sedating medications, and 26/196 (13%) were chemically paralyzed.

Table 1.

Patient and Injury Characteristics

| All: n = 196 | Colorado: 75 (38%) | Utah: 121 (62%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| mean ± SD | 6.7 ± 5.4 | 6.9 ± 5.7 | 6.7 ± 5.3 |

| Female | |||

| n (%) | 73 (37) | 24 (32) | 49 (40) |

| Injury Mechanism | |||

| Traffic: n (%) | 66 (34) | 31 (41) | 35 (29) |

| Fall: n (%) | 42 (21) | 12 (16) | 30 (25) |

| Abuse: n (%) | 43 (22) | 21 (28) | 22 (18) |

| Other: n (%) | 45 (23) | 11 (15) | 34 (28) |

| GCS - Total | |||

| 3: n (%) | 55 (28) | 18 (24) | 37 (31) |

| 4–8: n (%) | 78 (40) | 36 (48) | 42 (35) |

| 9–12: n (%) | 32 (16) | 14 (19) | 18 (15) |

| 13–15: n (%) | 31 (16) | 7 (9) | 24 (20) |

| GCS - Motor | |||

| 1: n (%) | 55 (28) | 18 (24) | 37 (31) |

| 2: n (%) | 12 (6) | 7 (9) | 5 (4) |

| 3: n (%) | 9 (5) | 5 (7) | 4 (3) |

| 4: n (%) | 38 (19) | 17 (23) | 21 (17) |

| 5: n (%) | 45 (23) | 23 (31) | 22 (18) |

| 6: n (%) | 37 (19) | 5 (7) | 32 (26) |

| Pupil Reactivity | |||

| Both Fixed: n (%) | 28 (14) | 15 (20) | 13 (11) |

| Both Reactive: n (%) | 150 (77) | 52 (69) | 98 (81) |

| One Reactive: n (%) | 7 (4) | 2 (3) | 5 (4) |

| Unknown: n (%) | 11 (6) | 6 (8) | 5 (4) |

| ICU LOS | |||

| median (IQR) | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (2, 10) | 2 (1, 5) |

| Hospital LOS | |||

| median (IQR) | 8 (4, 13) | 8 (4, 14) | 6 (3, 12) |

| Hospital Disposition | |||

| Home, no new supports: n (%) | 103 (53) | 33 (44) | 70 (58) |

| Mortality: n (%) | 28 (14) | 13 (17) | 15 (12) |

| Inpatient Rehabilitation: n (%) | 51 (26) | 27 (36) | 24 (20) |

| Other: n (%) | 14 (7) | 2 (3) | 12 (10) |

SD = standard deviation; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay; IQR = interquartile range.

Most of the patients, 133/196 (68%), had severe TBI (Appendix Table 2). Hospital mortality was 14% overall and 20% among those with severe TBI. The "Other" Hospital Disposition category includes children discharged home with new medical equipment or in-home care.

Hospital Discharge Functional Status Scale

Many children who survived to hospital discharge had impaired functional status. Nearly one-half of survivors had at least "mildly abnormal" functional status and more than one-quarter had at least "moderately abnormal" functional status (Table 2).(12) The mean FSS was 8.9 ± 4.0 and the median FSS was 7 (6, 10). Among patients with severe TBI, most, had at least "mildly abnormal" functional status and more than one-third, had at least "moderately abnormal" functional status (Appendix Table 3). For patients with severe TBI, the mean FSS was 9.9 ± 4.5 and the median FSS was 8 (6, 12).

Table 2.

Hospital Discharge FSS in Survivors

| All: n = 168 | Colorado: 62 (37%) | Utah: 106 (63%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total FSS | |||

| median (IQR) | 7 (6, 10) | 8 (6, 12) | 7 (6, 9) |

| mean (SD) | 9 ± 4 | 10 ± 5 | 8 ± 3 |

| Total FSS, categorical | |||

| 6–7 (Good): n (%) | 91 (54) | 31 (50) | 60 (57) |

| 8–9 (Mildly abnormal): n (%) | 28 (17) | 8 (13) | 20 (19) |

| 10–15 (Moderately abnormal): n (%) | 33 (20) | 12 (19) | 21 (20) |

| 16–21 (Severely abnormal): n (%) | 13 (8) | 8 (13) | 5 (5) |

| > 21 (Very severely abnormal): n (%) | 3 (2) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

FSS = Functional Status Scale. IQR = interquartile range. SD = standard deviation.

Functional Status Scale Domains

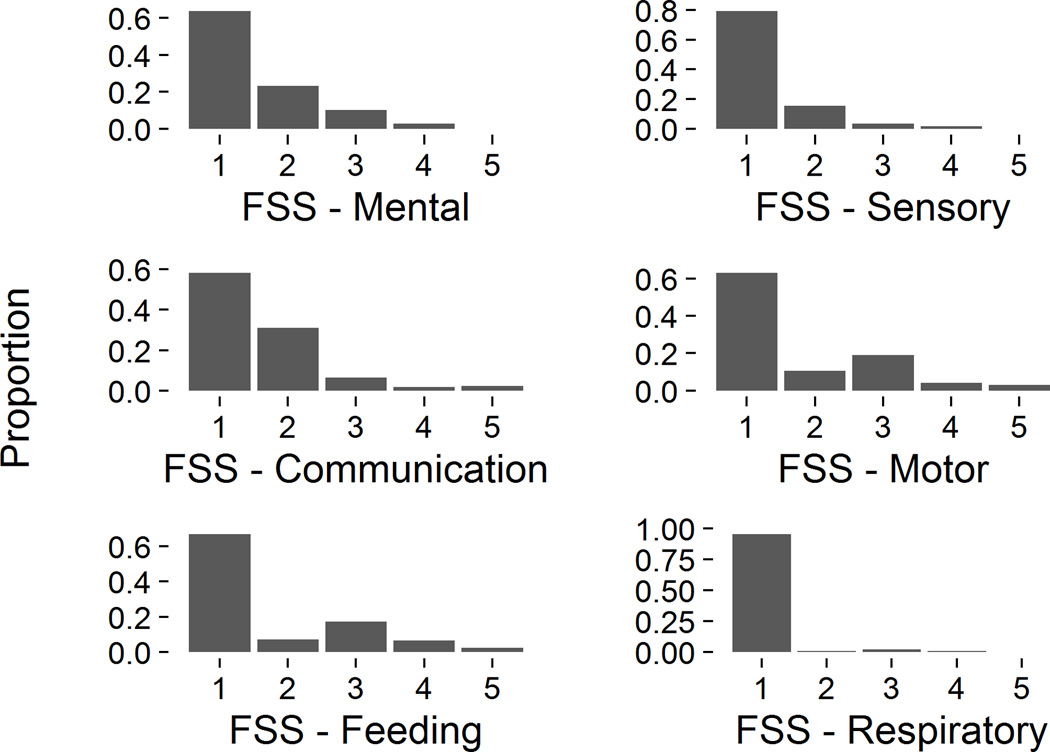

Functional impairment at hospital discharge was present for all of the 6 FSS domains, although less often in the Respiratory domain than the other 5 (Figure 1). Within each domain, the percent of survivors with dysfunction (domain score > 1) ranged from 5% (Respiratory) to 42% (Communication). Motor and Feeding dysfunction tended to be more severe than other types of dysfunction: the most common abnormal domain score was 2 (mild dysfunction) with the exception of the Motor and Feeding domains, in which the most common abnormal score was 3 (moderate dysfunction).

Figure 1. FSS Domain Scores at Hospital Discharge.

Histograms of Functional Status Scale (FSS) domain scores at hospital discharge. A score of 1 in each category represents no dysfunction.

Change in Functional Status Scale from Baseline

Baseline FSS data were only collected at CHCO. All but 1 survivor at CHCO (61/62) had a good functional status (FSS 6 or 7) prior to their injury (Table 3). The mean and median baseline FSS were 6.1 ± 0.5 and 6.0 (6.0, 6.0) respectively. The most common abnormality was isolated mild speech delay (FSS Communication = 2, FSS total = 7) (Appendix Table 1). More than one-third, 23/62 (37%), of all patients developed a new morbidity (change in FSS ≥ 3). Among all survivors, the mean change in FSS was +3.9 ± 4.9. In survivors of severe TBI, the mean change in FSS was +5.2 ± 5.4 and 21/41 (51%) were discharged with a new morbidity. The mean change in FSS domain score was highest for the Motor (+0.9 ± 1.2), Feeding (+0.9 ± 1.3), and Communication (+0.8 ± 1.0) domains and lowest for the Respiratory domain (+0.1 ± 0.6).

Table 3.

Change from Baseline FSS in Survivors

| All: n = 62 | Severe TBI: n = 41 (66.1%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline FSS | ||

| median (IQR) | 6 (6, 6) | 6 (6, 6) |

| mean (SD) | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 0.5 |

| Change in FSS, above baseline | ||

| median (IQR) | 1 (0, 6) | 4 (1, 9) |

| mean (SD) | 3.9 ± 4.9 | 5.2 ± 5.4 |

| Change in FSS, categorical | ||

| + < 2: n (%) | 33 (53) | 17 (41) |

| + 2: n (%) | 6 (10) | 3 (7) |

| + ≥ 3 (new morbidity): n (%) | 23 (37) | 21 (51) |

FSS = Functional Status Scale. IQR = interquartile range. SD = standard deviation.

Discharge FSS by Patient Age and Injury Mechanism

We examined associations of age and injury mechanism with discharge FSS using linear regression and found no direct relationship between patient age and discharge FSS: estimated change in discharge FSS per year increase in admission age −0.1 (95% CI: −0.3 to 0.0). Discharge FSS varied widely among those children injured by motor vehicle traffic, child abuse, and other mechanisms (linear regression P < 0.01). In children with falls who survived, discharge FSS was almost exclusively in the "good" or "mild dysfunction" categories. The mean discharge FSS for children injured in falls was 7.2 ± 2.8 compared to those injured by traffic incidents, 9.8 ± 4.6, child abuse, 10.1 ± 3.6, and other mechanisms, 8.6 ± 3.9.

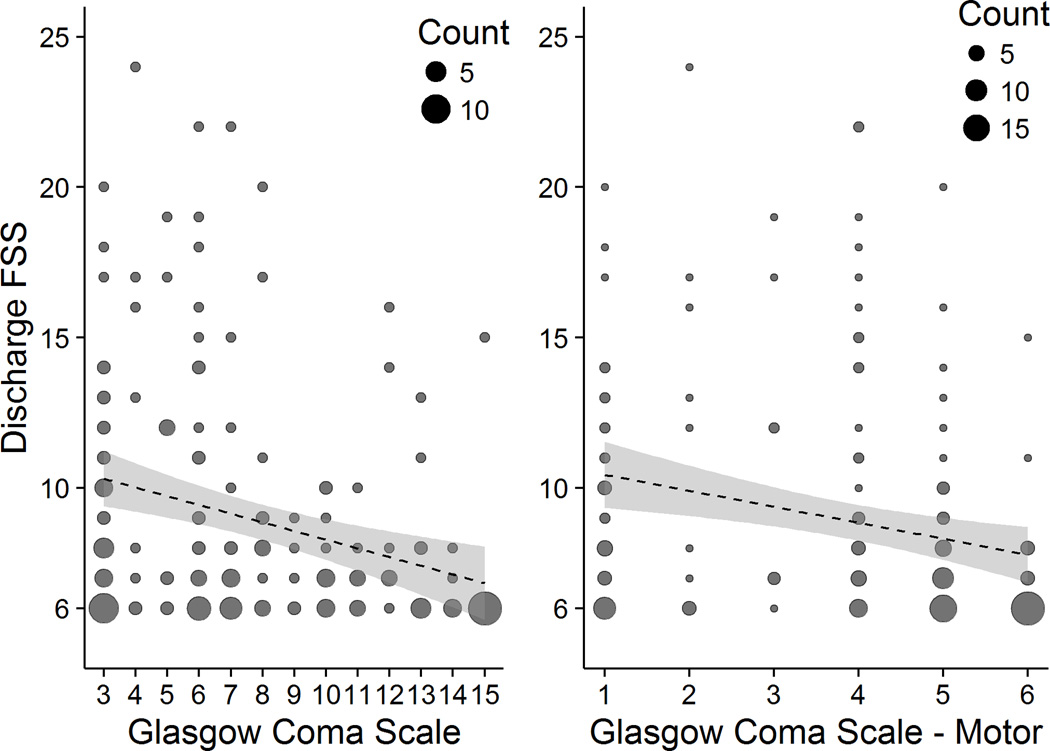

Discharge FSS and Admission GCS

The most common FSS score at hospital discharge was 6 (normal), and that score was found in children with every value of admission GCS (Figure 2). The mean discharge FSS ranged from 6.5 ± 0.8 for a GCS of 14 to 10.4 ± 4.8 for a GCS of 4. The mean discharge FSS ranged from 6.7 ± 1.8 for a GCS-Motor of 6 to 11.0 ± 6.0 for a GCS-Motor of 2. The variation in discharge FSS within GCS categories was higher for more severe injuries than milder injuries: 10th to 90th percentile range (width) = 11 for severe TBI and only 4 for mild or moderate TBI. To be included in this study, patients with "mild" TBI by GCS (13–15) had to be admitted to an ICU and receive a neurosurgical procedure in the first 24 hours. As expected, we found an inverse relationship between discharge FSS and admission GCS total and motor scores (Figure 2). Using linear regression, we estimated that for each 1 point higher admission GCS score, a patient's discharge FSS was 0.5 (95% CI: 0.7 to 0.3) points lower, P < 0.01.

Figure 2. Discharge FSS by Admission GCS and GCS - Motor.

FSS = Functional Status Scale; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale. A FSS score of 6 represents no dysfunction.

Discharge FSS and Admission Pupillary Reactivity

Most, 150/196 (77%), patients had bilaterally reactive pupils on admission to the ICU. Of the 28 patients who had bilaterally fixed pupils on admission to the ICU, 20 died. Among survivors, the mean discharge FSS ranged from 8.4 ± 3.3 for those with bilaterally reactive pupils on ICU admission to 15.0 ± 6.1 for those with bilaterally fixed pupils on ICU admission.

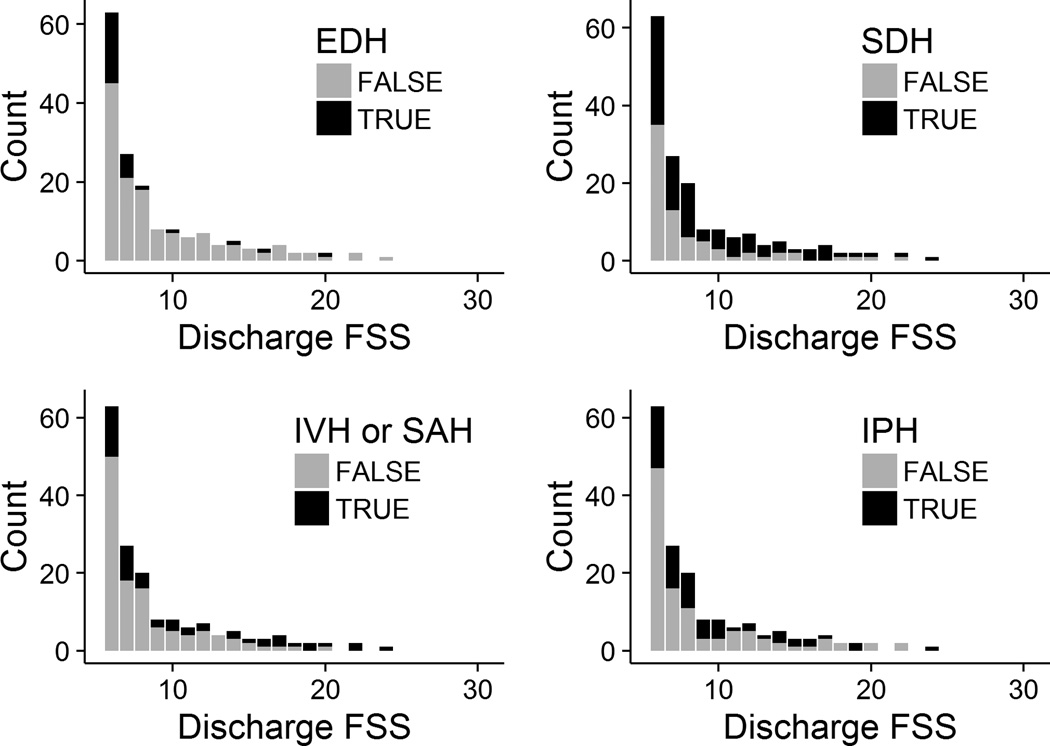

Discharge FSS and Admission CT Features

All study patients except 1 had a brain CT formally read by a site pediatric radiologist. That patient was transferred from another hospital where a brain CT was conducted and read, but no formal over-read was performed by the site radiologist. More than half of the study patients, 103/195 (53%), had a skull fracture and most, 171/195 (88%), had at least one type of intracranial hemorrhage. As expected, most 24/30 (80%) children with epidural hematoma (EDH) had good functional status at hospital discharge (Figure 3, mean FSS without EDH = 9.3 versus 7.5 with EDH, P = 0.02). Children with subdural (SDH), intraventricular (IVH), subarachnoid (SAH), or intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH) had more variable discharge functional status (Figure 3). Multiple hemorrhage types were often 80/194 (41%) present. The surviving patient with the worst functional status, for example, had SDH, SAH or IVH, and IPH. Surviving children with either IVH or SAH had higher discharge FSS scores, mean 10.7, than those who did not, mean 8.2 (P < 0.01).

Figure 3. Discharge FSS by Intracranial Hemorrhage Type.

EDH = epidural hematoma; SDH = subdural hematoma; IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage; SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage; IPH = intraparenchymal hemorrhage. A FSS score of 6 represents no dysfunction.

CT findings of cerebral edema, 82/195 (42%), and those consistent with local or diffuse intracranial hypertension such as basilar cistern compression, 50/195 (26%), and midline shift, 45/195 (23%), were not uncommon. Patients with cerebral edema and basilar cistern compression had higher mean discharge FSS values (13 versus 9 and 14 versus 9, both P < 0.01). We found no difference for patients with and without midline shift (11 versus 10, P = 0.46). However, patients who did and did not have these CT findings had widely varying discharge FSS values, from normal to severely impaired (not shown).

Nearly all, 29/30 (97%), of the patients with mild TBI had at least one type of intracranial hemorrhage. Of those 29 patients with "complicated" mild TBI(29), 1 (3%) died and the survivors had little or no apparent dysfunction at hospital discharge: mean FSS 7.0 ± 2.3 and median FSS 6 (6, 6).

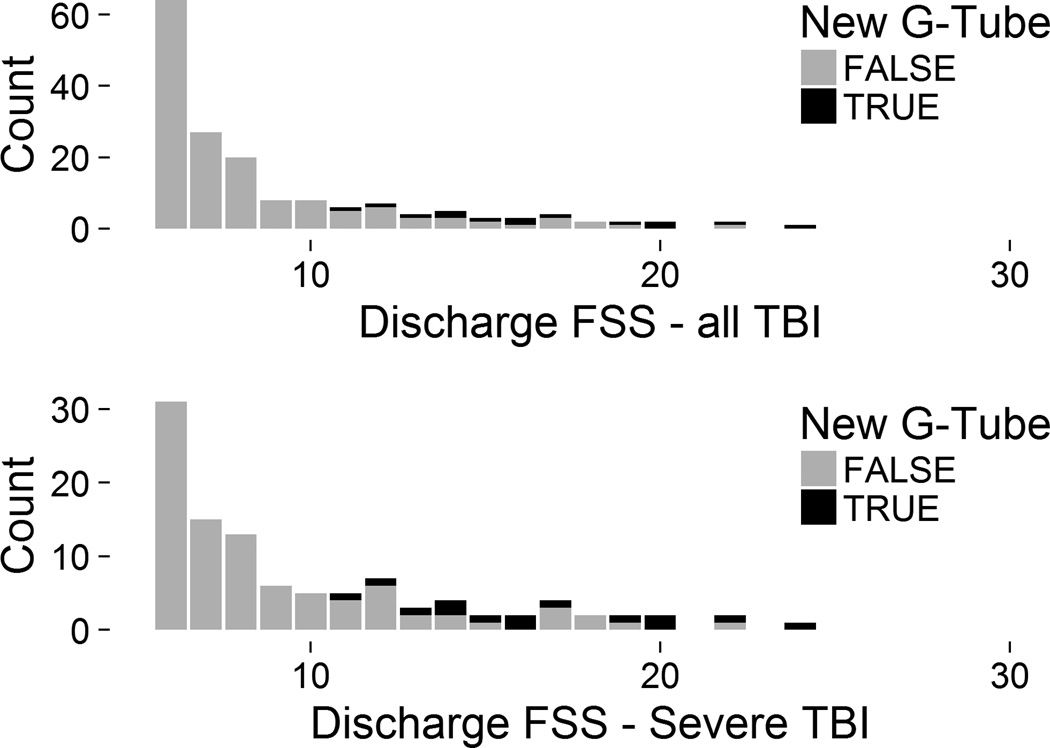

Discharge FSS and New Technology Dependence

More severely injured children may not be able to safely take adequate nutrition by mouth and may require placement of a new gastrostomy tube. Among survivors who received a new gastrostomy tube (n = 14) during their acute hospitalization, the mean discharge FSS was much higher: 17 versus 8, P < 0.01 (Figure 4). In children with severe TBI, the 14 children who received a new gastrostomy tube had a mean discharge FSS of 17 versus 9 in those who did not, P < 0.01. The distributions of discharge FSS values between patients who did and did not have a new gastrostomy tube separated well graphically: only those without new gastrostomy tubes had normal or mildly abnormal discharge FSS scores (Figure 4). Profoundly injured survivors may require a new tracheostomy. Of the 5 children who received a new tracheostomy, all 5 (100%) also received a gastrostomy and the mean discharge FSS was 15 ± 3.

Figure 4. Discharge FSS by New Gastrostomy status.

FSS = Functional Status Scale; G-Tube = gastrostomy tube; TBI = traumatic brain injury. A FSS score of 6 represents no dysfunction.

Discussion

In this 3-year prospective cohort study conducted at two large level 1 Pediatric Trauma Centers, we found that more than 90% of critically injured children with TBI had a normal or near-normal pre-injury FSS and more than one-third (37%) of survivors had a new morbidity at hospital discharge. Among children with severe TBI, approximately half (51%) of survivors had a new morbidity at hospital discharge. The mean change in FSS from baseline to hospital discharge was 3.9 in all survivors and 5.2 in survivors of severe TBI. Placement of a new gastrostomy tube during the acute hospitalization defines a group of survivors with at least moderately impaired functional status. Hospital discharge FSS was associated with some known predictors of TBI outcome such as injury mechanism, GCS and its Motor component, and CT findings including EDH and IVH or SAH, but not patient age.

This study is the first reported application of the FSS to a diagnosis-based population rather than a general PICU population. The new morbidity rate we observed, 37%, is much higher than the 4.6% – 4.8% overall or the 7.3% among patients with "Neurologic" primary dysfunction observed by the FSS development team.(12, 17) At pediatric trauma centers, children with TBI may make up a significant fraction of those in the overall PICU population who acquire new morbidities. As in the general PICU population, children with TBI acquired dysfunction in all 6 domains of the FSS, although less often in the Respiratory domain than the Mental, Sensory, Communication, Motor, and Feeding domains.(12)

Pollack et al. previously reported that the FSS is sensitive to change in function that would be classified within a single category of other simple outcome scales such as the PCPC/POPC system.(16) They found wider variation of FSS scores within PCPC/POPC categories representing more severe dysfunction. Similarly, we found greater variation of the discharge FSS for children with more severe GCS scores. Notably, because of the inclusion criteria of this study, all but one (29/30) of the patients with "mild" TBI had at least one type of intracranial hemorrhage. This is one type of "complicated mild" TBI(29) that has worse outcomes than mild TBI without intracranial hemorrhage. Significant variation in discharge FSS is also present within categories defined by other predictors of outcome in children with TBI such as injury mechanism and admission CT findings.

The FSS generally tracked with factors known to be associated with outcome in children with TBI. Children with poor prognostic factors such as bilaterally fixed pupils, low GCS, or gastrostomy tube placement had higher (worse) discharge FSS scores. Those with relatively good prognostic factors such as higher GCS had lower (better) discharge FSS scores.

This study has several limitations. First, the FSS is less granular than more detailed neuropyschological and cognitive instruments. It does not capture family functioning or quality of life.(16) The FSS would not capture pre- or post-injury morbidities such as seizures, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, mental health or behavioral problems, or learning problems.(8, 29) Second, we conducted this study at only two centers. They are likely representative of large ACS level 1 Pediatric Trauma Centers, but may not represent smaller trauma centers. Nonetheless, this study provides valuable pilot data for larger studies using FSS as an outcome. Third, we did not capture outcomes beyond hospital discharge, so inferences beyond hospital discharge cannot be made. Fourth, we did not independently assess each CT image, but rather extracted features from the formal reading conducted by the study site radiologists. Both sites are ACS level 1 Pediatric Trauma Centers staffed by board-certified pediatric radiologists. Chun et al. have reported good interobserver variability in identifying many of these CT features.(30)

Despite the limitations of the FSS, it has several advantages, which, taken together, make it useful for large studies in general and studies of TBI in particular. It has good construct validity: the FSS domains are generally consistent with activities of daily living (ADLs). The FSS accurately maps to more comprehensive adaptive behavior testing.(15) It adds significant granularity within each category of the PCPC or POPC, but can still be rapidly obtained.(16) It can be obtained from hospital caregivers with good interrater reliability and it can be used for patients of any age, unlike some adaptive behavior and health-related quality of life instruments. Unlike some more detailed instruments, the FSS is free and in the public domain. The FSS was designed for in-hospital use and when used during the acute hospitalization does not require extrapolation by the observer beyond the hospital setting (e.g. school performance or home ADLs).(4, 7) Although the FSS has not yet been applied to patients after hospital discharge, continuing serial measurements after return to home and community would generate patient function tracking using the same instrument from the acute hospitalization through the rehabilitative period.

The International Mission on Prognosis and Analysis of randomized Controlled Trials in TBI (IMPACT) studies have generated valuable outcome prediction models for adults with TBI.(19) No such model exists for children with TBI. However, the current study provides preliminary data for such a model using FSS as an outcome. This study was not powered to consider all potential outcome predictors simultaneously to determine their relative importance. However, patient age, injury mechanism, neurologic exam (pupillary reactivity, GCS, GCS-Motor), CT findings, and laboratory measures (glucose, hemoglobin) will need to be considered for that model.(19–21)

In conclusion, the FSS is a useful outcome measure for studies of critically injured children with TBI. A baseline FSS can be readily collected from hospital caregivers and the medical record, allowing measurement of change from pre-injury functional status in large studies. More than one-third of survivors, and approximately half of survivors with severe TBI, will have a new morbidity. Hospital discharge FSS, change from baseline FSS, and new morbidity acquisition can be used as outcome measures for hospital-based care process improvement initiatives and interventional studies of children with TBI.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (Grant K23HD074620 to TB) and the National Center for Research Resources (Colorado CTSI Grant UL1 TR001082).

We are indebted to Kris Hansen, Ryan Metzger, and the Trauma team at Primary Children's Hospital, to Michelle Loop and the Trauma team at Children's Hospital Colorado, and to Cody Olsen and Melissa Ringwood at the University of Utah Data Coordinating Center.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Functional Status Scale Domains

| Normal (Score = 1) |

Mild Dysfunction (Score = 2) |

Moderate Dysfunction (Score = 3) |

Severe Dysfunction (Score = 4) |

Very Dysfunction (Score = 5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Status |

Normal sleep/wake periods; appropriate responsivene ss |

Sleepy but arousable to noise/touch/movem ent and/or periods of social nonresponsiveness |

Lethargic and/or irritable |

Minimal arousal to stimuli (stupor) |

Unresponsive, coma, and/or vegetative state |

| Sensory Function |

Intact hearing and vision and responsive to touch |

Suspected hearing or vision loss |

Not reactive to auditory stimuli or to visual stimuli |

Not reactive to auditory stimuli and to visual stimuli |

Abnormal responses to pain or touch |

| Communicati on |

Appropriate noncrying vocalizations, interactive facial expressivene ss, or gestures |

Diminished vocalization, facial expression, and/or social responsiveness |

Absence of attention- getting behavior |

No demonstrati on of discomfort |

Absence of communication |

| Motor Functioning |

Coordinated body movements, normal muscle control, and awareness of action and reason |

1 limb functionally impaired |

2 or more limbs functionally impaired |

Poor head control |

Diffuse spasticity, paralysis, or decerebrate/decortic ate posturing |

| Feeding | All food taken by mouth with age- appropriate help |

Nothing by mouth or need for age- inappropriate help with feeding |

Oral and tube feedings |

Parenteral nutrition with oral or tube feedings |

All parenteral nutrition |

| Respiratory Status |

Room air and no artificial support or aids |

Oxygen treatment and/or suctioning |

Tracheosto my |

Continuous positive airway pressure treatment for all or part of the day and/or mechanical ventilatory support for part of the day |

Mechanical ventilatory support for all of the day and night |

Appendix Table 2.

Patient and Injury Characteristics - Severe TBI only

| All: n = 133 | Colorado: 54 (41%) | Utah: 79 (59%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 5.5 | 6.9 ± 5.8 | 7.4 ± 5.4 |

| Female | |||

| n (%) | 44 (33) | 15 (28) | 29 (37) |

| Injury Mechanism | |||

| Traffic: n (%) | 55 (41) | 23 (43) | 32 (41) |

| Fall: n (%) | 21 (16) | 6 (11) | 15 (19) |

| Abuse: n (%) | 30 (23) | 17 (31) | 13 (16) |

| Other: n (%) | 27 (20) | 8 (15) | 19 (24) |

| GCS - Total | |||

| 3: n (%) | 55 (41) | 18 (33) | 37 (47) |

| 4: n (%) | 9 (7) | 5 (9) | 4 (5) |

| 5: n (%) | 10 (8) | 6 (11) | 4 (5) |

| 6: n (%) | 28 (21) | 13 (24) | 15 (19) |

| 7: n (%) | 17 (13) | 7 (13) | 10 (13) |

| 8: n (%) | 14 (11) | 5 (9) | 9 (11) |

| GCS - Motor | |||

| 1: n (%) | 55 (41) | 18 (33) | 37 (47) |

| 2: n (%) | 12 (9) | 7 (13) | 5 (6) |

| 3: n (%) | 8 (6) | 4 (7) | 4 (5) |

| 4: n (%) | 34 (26) | 16 (30) | 18 (23) |

| 5: n (%) | 20 (15) | 9 (17) | 11 (14) |

| 6: n (%) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) |

| Pupil Reactivity | |||

| Both Fixed: n (%) | 27 (20) | 15 (28) | 12 (15) |

| Both Reactive: n (%) | 91 (68) | 34 (63) | 57 (72) |

| One Reactive: n (%) | 6 (5) | 1 (2) | 5 (6) |

| Unknown: n (%) | 9 (7) | 4 (7) | 5 (6) |

| ICU LOS | |||

| median (IQR) | 3 (2, 8) | 4 (2, 10) | 3 (1, 6) |

| Hospital LOS | |||

| median (IQR) | 9 (4, 15) | 10 (4, 16) | 9 (4, 14) |

| Hospital Disposition | |||

| Home, no new supports: n (%) | 55 (41) | 17 (31) | 38 (48) |

| Mortality: n (%) | 27 (20) | 13 (24) | 14 (18) |

| Inpatient Rehabilitation: n (%) | 42 (32) | 23 (43) | 19 (24) |

| Other: n (%) | 9 (7) | 1 (2) | 8 (10) |

SD = standard deviation; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay; IQR = interquartile range.

Appendix Table 3.

Hospital Discharge FSS - Severe TBI only

| All: n = 106 | Colorado: 41 (39%) | Utah: 65 (61%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total FSS | |||

| median (IQR) | 8 (6, 12) | 10 (7, 15) | 8 (6, 10) |

| mean (SD) | 10 ± 4 | 11 ± 5 | 9 ± 4 |

| Total FSS, categorical | |||

| 6–7 (Good): n (%) | 46 (43) | 15 (37) | 31 (48) |

| 8–9 (Mildly abnormal): n (%) | 19 (18) | 5 (12) | 14 (22) |

| 10–15 (Moderately abnormal): n (%) | 26 (25) | 11 (27) | 15 (23) |

| 16–21 (Severely abnormal): n (%) | 12 (11) | 7 (17) | 5 (8) |

| > 21 (Very severely abnormal): n (%) | 3 (3) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) |

IQR = interquartile range. SD = standard deviation.

References

- 1.Faul M, Likang X, Wald M, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the united states: Emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention; Control, Centers for Disease Control; Prevention, U.S. Department of Health; Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frieden T, Houry D, Baldwin G. Report to congress on traumatic brain injury in the united states: Epidemiology and rehabilitation. Division for Unintentional Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention; Control, Centers for Disease Control; Prevention, U.S. Department of Health; Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 1992;121:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiser DH, Long N, Roberson PK, et al. Relationship of pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scores at pediatric intensive care unit discharge with outcome measures collected at hospital discharge and 1- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2616–2620. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiser DH, Tilford JM, Roberson PK. Relationship of illness severity and length of stay to functional outcomes in the pediatric intensive care unit: A multi-institutional study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1173–1179. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett TD. Functional status after pediatric critical care: Is it the disease, the cure, or both? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:377–378. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beers SR, Wisniewski SR, Garcia-Filion P, et al. Validity of a pediatric version of the glasgow outcome scale-extended. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1126–1139. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crouchman M, Rossiter L, Colaco T, et al. A practical outcome scale for paediatric head injury. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:120–124. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namachivayam P, Shann F, Shekerdemian L, et al. Three decades of pediatric intensive care: Who was admitted, what happened in intensive care, and what happened afterward. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:549–555. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181ce7427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slonim AD, Khandelwal S, He J, et al. Characteristics associated with pediatric inpatient death. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1208–1216. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bone MF, Feinglass JM, Goodman DM. Risk factors for acquiring functional and cognitive disabilities during admission to a pICU*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:640–648. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Pediatric intensive care outcomes: Development of new morbidities during pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:821–827. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choong K, Al-Harbi S, Siu K, et al. Functional recovery following critical illness in children: The “wee-cover” pilot study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:310–318. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000227106.66902.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. Functional status scale: New pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e18–e28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Relationship between the functional status scale and the pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scales. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:671–676. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Simultaneous prediction of new morbidity, mortality, and survival without new morbidity from pediatric intensive care: A new paradigm for outcomes assessment. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1699–1709. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maas AI, Hukkelhoven CW, Marshall LF, et al. Prediction of outcome in traumatic brain injury with computed tomographic characteristics: A comparison between the computed tomographic classification and combinations of computed tomographic predictors. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1173–1182. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000186013.63046.6b. discussion 1173-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maas AIR, Murray GD, Roozenbeek B, et al. Advancing care for traumatic brain injury: Findings from the iMPACT studies and perspectives on future research. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:1200–1210. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liesemer K, Riva-Cambrin J, Bennett KS, et al. Use of Rotterdam CT scores for mortality risk stratification in children with traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:554–562. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tasker RC. CT characteristics, risk stratification, and prediction models in traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:569–570. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (rEDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Trauma Data Standard of the NTDB [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tufte ER. The visual display of quantitative information. 2nd. Graphics Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team: R. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allaire J, Cheng J, Xie Y, et al. Rmarkdown: Dynamic documents for r. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie Y. Knitr: A general-purpose package for dynamic report generation in r. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wickham H, Chang W. Ggplot2: An implementation of the grammar of graphics. RStudio. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Wang J, et al. Disability 3, 12, and 24 months after traumatic brain injury among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1129–e1138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chun KA, Manley GT, Stiver SI, et al. Interobserver variability in the assessment of CT imaging features of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:325–330. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]