Abstract

A 15-year-old male cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) showed large bilateral masses in the maxillary sinus. In histopathological examination, both masses revealed benign medullary lipomas within the turbinate bones. The tumors were composed of well-developed lipocytes, trabecular bones and a few blood vessels. Although we initially diagnosed the tumor as bilateral lipomas in the nasal turbinates, it was not differentiated from lipomatous hamartoma. Findings, such as unique symmetrical proliferation, lack of border from the normal marrow and the intact surrounding tissue, indicated a lipomatous hamartoma/hamartomatous lipoma, thought to be a suitable diagnosis of the lesion. Of most interest was that such a proliferating lesion occurred in the nasal turbinate.

Keywords: hamartoma, medullary lipoma, monkey, nasal turbinate

In humans, intraosseous lipoma frequently occurs within long bones, such as humerus, rib, femur and tibia [3, 6, 23]. The tumor also develops in the skull, ilium and calcaneus [3, 4, 14, 23]. Moreover, with development of pertinent imaging studies, including computed tomographic (CT) scans and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lipomas of the skull base [17], nasopharynx [11], sphenoid bone [21, 29] and others [7, 9, 10, 13] are reported with an increasing tendency. Intraosseous lipomas are subdivided into three groups, depending on the degree of involution [24]. Once the tumor affects a long bone or a bone with wide marrow space, the tumor tissue extends into the marrow space [3, 12, 15, 34]. Such a lipoma is called “medullary”. However, it has been regarded as an intraosseous lipoma [3, 8]. The tumor of the nasal turbinate is an extremely rare event in humans [1, 22]. In animals, intraosseous lipomas have been detected only in the long bones [25]. Recently, we encountered a tumor-like lesion in the nasal turbinate bone of a cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). In this report, we describe the characteristics of the lesion and discuss the diagnosis.

The monkey, a 15-year-old male, was purchased from Keari Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) at 3 years old. This monkey had then been used in some pharmaceutical studies relating to ophthalmology together with other monkeys. These monkeys were individually housed in stainless steel cages (800 mm wide × 823 mm deep × 690 mm high; Keari Co., Ltd.) maintained in a climate-controlled animal room (temperatures ranging between 18 and 28 ºC; relative humidity, 30 and 70%; and ventilation, approximately 10 or more cycles/hr of filtered fresh air) with a 12-hr light/dark cycle (7:00–19:00) and were given ad libitum access by an automated system to tap water and a solid food of approximately 100 g/day (Monkey Bit; Nosan Co., Yokohama, Japan). Enrichments were provided for the monkeys during the housing. The treatment and handling of animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Nara Research & Development Center, Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

This monkey was enrolled in an ophthalmic study in which it was treated as a human ocular disease model in September, 2014. The animal was not administered any ocular drugs and was clinically healthy except that both eyes had received a surgical operation. At the end of the study, the animal was euthanized by exsanguination from the axillary artery and abdominal aorta under deep anesthesia by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (Somnopentil®; Kyoritsu Seiyaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

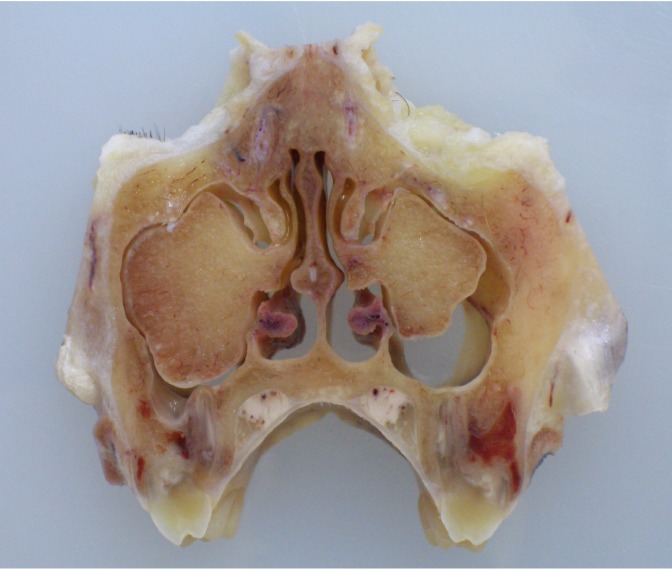

At necropsy, the appearance of the nose was normal. After fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin, during a cross-section procedure on the nose, large bilateral masses were found at both tips of the middle turbinates (Fig. 1). The longitudinal lengths of the right and left masses were 2 cm and 1.2 cm, respectively. Each mass had passed through the maxillary hiatus, grown in the maxillary sinus on each side and occupied the cavity (Fig. 1). The cut surface of the masses was yellowish and hard and had a sandy texture (Fig. 1). Microscopical examination was performed only on both eyes and the nasal cavity. The nasal bone including the masses was decalcified in a commercial reagent (KalkitoxTM; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) for 2 days at 4ºC. Decalcified nasal samples were examined histopathologically with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, Watanabe’s silver impregnation method and immunohistochemically.

Fig.1.

Macroscopic features of the bilateral masses that occupied the maxillary sinus cavities.

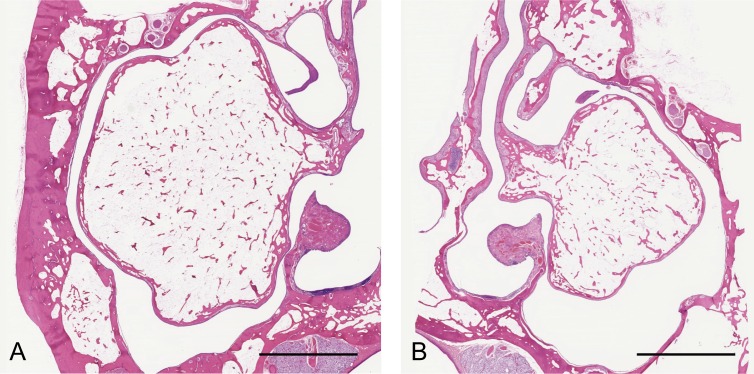

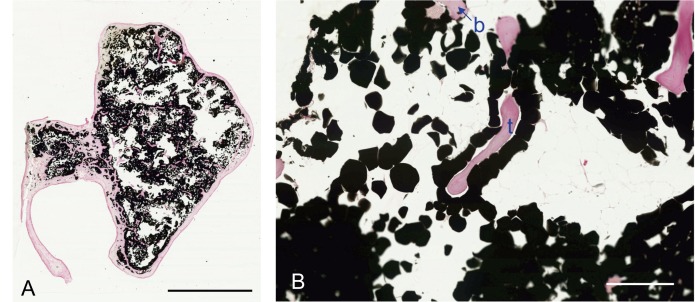

Within the nasal cavity of a normal monkey, the dosal, middle (ethmoid) and abdominal turbinates are observed as having a bilateral symmetric pattern separated by the nasal septum. These turbinates are covered with four kinds of lining epithelium. Both the dosal and middle turbinates have a bony shaft in the center. The tip of the bone has a wide marrow containing fatty tissue. In this case, both masses revealed benign lipomas within the marrow of turbinate bones. The cortical bone changed thinner, because of expansion of the tumor tissue. The tumors were composed of well-developed lipocytes, a lot of mature trabecular bones and a few blood vessels (Fig. 2A and 2B). The lipocytic tumor cells that reacted positively for osmium staining [20] (Fig. 3A and 3B) were divided from each other by a mesh-work of argyrophilic scanty fiber with no lobular formation. There were no findings associated with malignancy, such as lipoblast formation, increase in mitotic figures, hemorrhage or necrosis. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells only reacted positively for vimentin (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany, optimal dilution was 1:100) (Fig. 4). Equivocal reactivity showed Ki-67 (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A.) and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Dako Japan, Tokyo, Japan), possibly because of the decalcification procedure. Although the tumors were large, they did not destroy the surrounding tissue or disturb the air-way route in the nasal passages. According to these findings, we initially diagnosed this tumor-like lesion as a simple lipoma in the bone marrow of bilateral nasal turbinates. However, we could not differentiate this case from lipomatous hamartoma. The unique symmetrical proliferation, lack of border from the normal marrow and the intact surrounding tissue might indicate slow growth over a long time. There also might be a lipomatous bud in the ethmoid tissue at an embryo time. Lipomatous hamartoma/hamartomatous lipoma is used as a synonym of lipoma [16, 28, 31]. This case was discussed at the 55th veterinary pathology slide forum at the 2nd meeting of the Japanese College of Veterinary Pathologists (JCVP) in March, 2015. The result in this case was temporarily diagnosed as myelolipoma. Marrow cells were possibly replaced by fatty tissues with aging. According to the literature [2, 18, 19, 26, 27, 32, 33], however, hematopoietic elements are always detected in the lesion, even if the affected animals [28, 30] and patients [5] are of old age. In this case, no hematopoietic cells were observed at all in the proliferating lesion. By reason of this point, the diagnosis of myelolipoma was not appropriate for the tumor-like lesion.

Fig. 2.

Low magnification of the tumors (A, on the right side; and B, on the left side). These tumors are connected to the middle turbinates and had grown in the turbinate bones. HE, Bar=5 mm.

Fig. 3.

Osmium staining of the tumor. The tumor is composed of osmium-positive lipocytes, a lot of mature trabecular bones (t) and a few blood vessels (b). Counterstained with nuclear fast red. A, Bar=5 mm; B, Bar=100 μm.

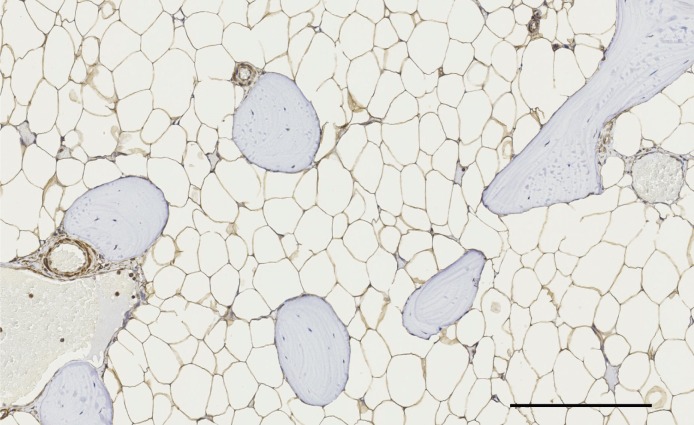

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry. The tumor cells were positive for vimentin. Counterstained with hematoxylin. Bar=50 μm.

At any rate, whether this case is diagnosed lipomatous hamartoma or real lipoma in the bone marrow is of minor interest. The most interesting aspect is that such a proliferative lesion occurred in the nasal turbinate. These cases are extremely rare, even in the humans. According to our own survey, there has been no other report in any animal. This case is therefore possibly the first of lipomatous lesions in the nasal turbinate in an animal. We will accumulate these cases to clarify their biological behavior and cytological characteristics.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members being at the 55th veterinary pathology slide forum for their instructive advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdalla W. M. A., da Motta A. C. B. S., Lin S. Y., McCarthy E. F., Zinreich S. J.2007. Intraosseous lipoma of the left frontoethmoidal sinuses and nasal cavity. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 28: 615–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Rukibat R. K., Bani Ismail Z. A.2006. Unusual presentation of splenic myelolipoma in a dog. Can. Vet. J. 47: 1112–1114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barcelo M., Pathria M. N., Abdul-Karim F. W.1992. Intraosseous lipoma. A clinicopathologic study of four cases. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 116: 947–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertram C., Popken F., Rütt J.2001. Intraosseous lipoma of the calcaneus. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 386: 313–317. doi: 10.1007/s004230100202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bovo G., Picozzi S. C. M., Viganò P., Giuberti A., Casu M., Manganini V., Mazza L., Strada G. R.2007. Giant adrenal myelolipoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 59: 455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell R. S. D., Grainger A. J., Mangham D. C., Beggs I., Teh J., Davies A. M.2003. Intraosseous lipoma: report of 35 new cases and a review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 32: 209–222. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0616-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castilho R. M., Squarize C. H., Nunes F. D., Pinto Júnior D. S.2004. Osteolipoma: a rare lesion in the oral cavity. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 42: 363–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow L. T., Lee K. C.1992. Intraosseous lipoma. A clinicopathologic study of nine cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 16: 401–410. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199204000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Freitas Silva B. S., Yamamoto F. P., Pontes F. S. C., Fonseca F. P., Pontes H. A. R., Pinto D. S., Jr2011. Intraosseous lipoma of the mandible: A diagnostic challenge. Rev. Odonto. Cienc. 26: 182–186. doi: 10.1590/S1980-65232011000200016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diom E. S., Ndiaye I. C., Ndiaye M., Thiam A., Tall A., Nao E. E. M., Diallo B. K., Diouf R., Diop E. M.2011. Osteolipoma: an unusual tumor of the parotid region. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 128: 34–36. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durmaz A., Tosun F., Kurt B., Gerek M., Birkent H.2007. Osteolipoma of the nasopharynx. J. Craniofac. Surg. 18: 1176–1179. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e31814b2b61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eyzaguirre E., Liqiang W., Karla G. M., Rajendra K., Alberto A., Gatalica Z.2007. Intraosseous lipoma. A clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study of 5 cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 11: 320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gokul S., Ranjini K. V., Kirankumar K., Hallikeri K.2009. Congenital osteolipoma associated with cleft palate: a case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 38: 91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto T., Kojima T., Iijima T., Yokokura S., Motoi T., Kawano H., Yamamoto A., Matsuda K.2002. Intraosseous lipoma: a clinical study of 12 patients. J. Orthop. Sci. 7: 274–280. doi: 10.1007/s007760200046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guirro P., Saló G., Molina A., Lladó A., Puig-Verdié L., Ramírez-Valencia M.2015. Cervical paravertebral osteolipoma: case report and literature review. Asian Spine J. 9: 290–294. doi: 10.4184/asj.2015.9.2.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha J. F., Teh B. M., Abeysuriya D. T. D., Luo D. Y. W.2012. Fibrolipomatous hamartoma of the median nerve in the elbow: a case report. Ochsner J. 12: 152–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazarika P., Pujary K., Kundaje H. G., Rao P. L.2001. Osteolipoma of the skull base. J. Laryngol. Otol. 115: 136–139. doi: 10.1258/0022215011907532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heard D. J., Fox L. E., Fox J., Neuwirth L., Raskin R.1996. Antemortem diagnosis of myelolipoma-associated hepatomegaly in a goeldi’s monkey (Callimico Goeldii). J. Zoo Anim. Med. 27: 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kakinuma C., Harada T., Watanabe M., Shibutani Y.1994. Spontaneous adrenal and hepatic myelolipomas in the common marmoset. Toxicol. Pathol. 22: 440–445. doi: 10.1177/019262339402200410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luna L. G.1968. Osmium tetroxide method for fat (paraffin sections). pp. 143–145. In: Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 3rd ed. (Luna, L. G. ed.), McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacFarlane M. R., Soule S. S., Hunt P. J.2005. Intraosseous lipoma of the body of the sphenoid bone. J. Clin. Neurosci. 12: 105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmood N. S.2010. An extremely rare case of a nasal turbinate lipoma. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 39: 64. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/65109233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milgram J. W.1988. Intraosseous lipomas. A clinicopathologic study of 66 cases. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 277–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milgram J. W.1990. Malignant transformation in bone lipomas. Skeletal Radiol. 19: 347–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00193088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakladal B., vom Hagen F., Olias P., Brunnberg L.2012. Intraosseous lipoma in the ulna and radius of a two-year-old Leonberger. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 25: 144–148. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-11-03-0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narama I., Nagatani M., Tsuchitani M., Inagaki H.1985. Myelolipomas in adult Goeldi’s monkeys (Callimico goeldii). Jpn. J. Vet. Sci. 47: 549–555. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.47.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozaki K., Kinoshita H., Kurasho H., Narama I.1996. Cutaneous myelolipoma in a peach-faced lovebird (Agapornis roseicollis). Avian Pathol. 25: 131–134. doi: 10.1080/03079459608419126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki T., Yoshizawa K., Kinoshita Y., Miki H., Kimura A., Yuri T., Uehara N., Tsubura A.2012. Spontaneously occurring intracranial lipomatous hamartoma in a young BALB/c mouse and a literature review. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 25: 179–182. doi: 10.1293/tox.25.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srubiski A., Csillag A., Timperley D., Kalish L., Qiu M. R., Harvey R. J.2011. Radiological features of the intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 144: 617–622. doi: 10.1177/0194599810392878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein F. J., Smallwood J. E., Tangner C. H., Jr, Hightower D., Joiner G. N.1982. A juxtarenal myelolipoma in a cottontop marmoset (Saguinus oedipus): A case report. Am. J. Primatol. 2: 215–221. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350020211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stey C. A., Vogt P., Russi E. W.1998. Endobronchial lipomatous hamartoma: a rare cause of bronchial occlusion. Chest 113: 254–255. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.1.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storms G., Janssens G.2013. Intraocular myelolipoma in a dog. Vet. Ophthalmol. 16Suppl 1: 183–187. doi: 10.1111/vop.12059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yanai T., Taniguchi H., Sakai H., Yoshida K., Kimura N., Katou A., Oishi Y., Masegi T.1996. Bilateral giant myelolipoma in the adrenal of a cotton-top tamarin (Saguinus oedipus). J. Med. Primatol. 25: 309–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yazdi H. R., Rasouli B., Borhani A., Noorollahi M. M.2014. Intraosseous lipoma of the femor: Image findings. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 4: 35–38. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]