Abstract

Overdose of acetaminophen (APAP) causes severe liver injury and even acute liver failure in both mice and human. A recent study by Kim et al. (2015, Metformin ameliorates acetaminophen hepatotoxicity via Gadd45β-dependent regulation of JNK signaling in mice. J. Hepatol. 63, 75–82) showed that metformin, a first-line drug to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus, protected against APAP hepatotoxicity in mice. However, its exact protective mechanism has not been well clarified. To investigate this, C57BL/6J mice were treated with 400 mg/kg APAP and 350 mg/kg metformin was given 0.5 h pre- or 2 h post-APAP. Our data showed that pretreatment with metformin protected against APAP hepatotoxicity, as indicated by the over 80% reduction in plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities and significant decrease in centrilobular necrosis. Metabolic activation of APAP, as indicated by glutathione depletion and APAP-protein adducts formation, was also slightly inhibited. However, 2 h post-treatment with metformin still reduced liver injury by 50%, without inhibition of adduct formation. Interestingly, neither pre- nor post-treatment of metformin inhibited c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation or its mitochondrial translocation. In contrast, APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress and dysfunction were greatly attenuated in these mice. In addition, mice with 2 h post-treatment with metformin also showed significant inhibition of complex I activity, which may contribute to the decreased mitochondrial oxidant stress. Furthermore, the protection was reproduced in JNK activation-absent HepaRG cells treated with 20 mM APAP followed by 0.5 or 1 mM metformin 6 h later, confirming JNK-independent protection mechanisms. Thus, metformin protects against APAP hepatotoxicity by attenuating the mitochondrial oxidant stress and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction, and may be a potential therapeutic option for APAP overdose patients.

Keywords: acetaminophen hepatotoxicity, metformin, mitochondria, oxidant stress, c-jun N-terminal kinase.

Acetaminophen (APAP) is a safe and effective analgesic and antipyretic at therapeutic doses. However, an overdose leads to the excessive formation of a reactive metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which depletes glutathione (GSH) and binds to mitochondrial proteins (Nelson, 1990). The well-documented inhibition of mitochondrial respiration (Donnelly et al., 1994; Meyers et al., 1988), mitochondrial oxidant stress and mitochondrial peroxynitrite formation (Cover et al., 2005; Jaeschke, 1990) after APAP overdose are thought to be initiated by the formation of APAP adduct on proteins of the electron transport chain (ETC). The subsequent mitochondrial oxidant stress triggers the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition (MPT) pore opening, resulting in the collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential, release of mitochondrial endonucleases and finally cell necrosis (Bajt et al., 2006; Hanawa et al., 2008; Kon et al., 2004). Currently, APAP overdose is the primary cause of acute liver failure in the United States and many Western countries (Budnitz et al., 2011; Manthripragada et al., 2011). N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was introduced as a clinical antidote for APAP overdose patients in the 1970s (Prescott et al., 1977). Until today, it is still the only available antidote despite its limited effectiveness, with early presenting patients benefitting most (Larson, 2007). Therefore, novel therapeutic agents are needed, especially for patients presenting late after an overdose. However, despite the large number of potential therapeutic agents that has been identified in animal models or hepatocytes over the last several decades, the enormous costs of developing a new drug specifically for a disease with a limited number of patients is prohibitive. Therefore, the best chance of getting a new antidote against APAP overdose is by re-purposing an existing drug.

Despite some controversies, c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) has emerged as a promising therapeutic target against APAP toxicity (Du et al., 2015b). The majority of studies suggested that JNK activation is detrimental in APAP overdose, and JNK deficiency or inhibition protected against APAP hepatotoxicity in murine models (Gunawan et al., 2006; Hanawa et al., 2008; Henderson et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2010a) and in primary human hepatocytes (Xie et al., 2014). More recently, metformin, a first-line drug for type 2 diabetes, was shown to protect against APAP hepatotoxicity in mice by inhibiting JNK activation (Kim et al. 2015). This is particularly interesting given that metformin is a marketed drug, which could be readily used to treat APAP overdose patients if its effectiveness is demonstrated. However, several serious concerns exist regarding the interpretation of the data in this study (Kim et al. 2015). The effect of metformin on metabolic activation of APAP, which needs to be ruled out before claiming any other protective mechanisms, was not carefully addressed (Kim et al. 2015). This is a very important issue as a number of recently identified potential therapeutic agents such as the purinergic receptor antagonist A438079, the gap junction inhibitor 2-aminoethoxy-diphenyl-borate, and the toll-like receptor 4 antagonist benzyl alcohol turned out to be simply inhibitors of the metabolic activation of APAP and both the mechanistic interpretation and the clinical potential are highly questionable (Du et al., 2013, 2015a; Xie et al., 2013). Also, because previous studies proposed that JNK activation serves to amplify the APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress and to aggravate subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction (Hanawa et al., 2008; Saito et al., 2010a), effects of metformin on these events need to be investigated. In addition, considering some differences between the mouse model and the human pathophysiology, it is important to further test the effectiveness of metformin in the human HepaRG cell line, where APAP-induced cell death closely resembles the human pathophysiology (McGill et al., 2011).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. Male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Lab, Bar Harbor, ME) of the age of 8–12 weeks were housed in environmentally controlled rooms with a 12 h light/dark cycle and allowed free access to food and water. Experiments followed the criteria of the National Research Council for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Experimental design. After overnight fasting (16 h), mice were treated (i.p.) with 400 mg/kg APAP (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in warm saline. Metformin (350 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich) or its vehicle saline (20 ml/kg) was administered (p.o.) 0.5 h before or 2 h after APAP. Mice were euthanized at 0–24 h post-APAP and blood and livers were harvested. Blood was drawn into heparinized syringes for measurement of plasma ALT activity. The liver tissue was sectioned into pieces for mitochondrial isolation as described (Du et al., 2015a), fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for histology, or flash frozen for determination of glutathione (GSH), APAP-cysteine adducts on proteins and Western blotting.

Biochemical assays. The ALT activity was measured using the ALT (SGPT) Reagent Kit (Pointe Scientific, MI, A7526-625) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured as described in detail (Du et al., 2013). Liver GSH and GSSG measurements were performed using a modified method of the Tietze assay (Jaeschke and Mitchell 1990; McGill and Jaeschke, 2015). APAP-protein adducts in liver tissues and mitochondrial pellets were measured as described (McGill et al., 2012; Ni et al., 2012). Complex I activity was measured in isolated mitochondria as described (Janssen et al., 2007). MitoSOX fluorescence in isolated mitochondria was measured as described (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007). Briefly, 250 μg freshly isolated mitochondria were incubated with isolation buffer containing respiratory substrates including 5 mmol/l malate, glutamate and succinate. A total of 5 μmol/l MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen) was added and fluorescence was read at 510/580 nm for 30 min (excitation/emission).

Histology and western blotting. Formalin-fixed tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for necrosis assessment (Gujral et al., 2002). Nitrotyrosine staining was performed as described (Knight et al., 2002), using a rabbit polyclonal anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and the Dako LSAB peroxidase kit (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). DNA strand breaks were assessed by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Western blotting was performed using the following antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) unless stated otherwise: rabbit anti-Bax polyclonal antibody (#27742), rabbit anti-AIF antibody (#5318), rabbit anti-JNK antibody (#9252), and a rabbit anti-phospho-JNK antibody (# 9251), MitoProfile OXPHOS Cocktail for CI-NDUFB8 (#110413) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), mouse anti-phospho-JNK antibody (#6254) (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), and mouse anti-Smac/DIABLO antibody (# 612245) (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), as described (Bajt et al., 2000).

HepaRG cell culture. HepaRG cells were obtained from Biopredic International (Rennes, France) and cultured as described previously (McGill et al., 2011). The cells were treated with 20 mM APAP and 0.5 or 1 mM metformin was added 6 h post-APAP. Cells were harvested at 24 h for the Seahorse XF assay or at 48 h for LDH activity measurement, as described (Bajt et al., 2004).

Seahorse XF-assay. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured in real-time using the Seahorse XF243 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA) as per manufacturer guidelines. Briefly, HepaRG cells were seeded in 24-well Seahorse microplates at 1 × 104 cells/well. The XF24 sensor cartridge was hydrated with 1 ml calibration buffer per well overnight at 37 °C. The sensor cartridge was loaded with oligomycin (1 μM, port A), carbonyl cyanide 4-trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 0.5 μM, port B), and rotenone plus antimycin-A (1 μM each, port C) to measure the bioenergetics profile. Cells were washed two times with pre-warmed XF assay medium containing 25 mM glucose and incubated in XF assay medium at 37 °C without CO2. Once the sensor cartridge was equilibrated, the calibration plate was replaced with the cell plate to measure OCR.

Statistics. All results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between two groups was evaluated using Student's t-test, whereas comparisons of multiple groups was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student–Newman–Keul’s test. For non-normally distributed data, Kruskal–Wallis Test (non-parametric ANOVA) was used followed by Dunn’s Multiple Comparisons Test. P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Pretreatment With Metformin Protected Against APAP-Induced Liver Injury

The APAP overdose (400 mg/kg) caused severe liver injury at 6 and 24 h post-APAP in mice, as indicated by the increased plasma ALT activities (Figure 1A) and extensive centrilobular necrosis in H&E-stained slides (Figure 1B and C). Pre-treatment with metformin (350 mg/kg) attenuated the increase in ALT activities by 80% (Figure 1A) and significantly decreased areas of necrosis at both time points (Figure 1B and C) demonstrating that metformin effectively protected against APAP hepatotoxicity.

FIG. 1.

Metformin protected against APAP hepatotoxicity. Mice were treated with 350 mg/kg metformin followed by 400 mg/kg APAP 0.5 h later. Blood and liver tissue were obtained at 0, 2, 6, or 24 h post-APAP. A, Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity. B, Areas of necrosis (%). C, H&E staining of representative liver sections. Bars represent means ± SEM for n = 3 − 6 mice. *P < .05 compared with 0 h; #P < .05 compared with respective APAP group.

Metformin Inhibited APAP Metabolic Activation But Did Not Affect JNK Activation

Metabolic activation of APAP forms the reactive metabolite NAPQI, which depletes GSH, binds to cellular proteins and forms APAP-protein adducts (Mitchell et al., 1973; Nelson, 1990). To assess whether metformin interferes with APAP metabolic activation, APAP-protein adducts were measured 2 h post-APAP, which is close to the peak levels of adducts (McGill et al., 2013). Our data showed that metformin significantly reduced APAP-protein adducts formation in both the total liver homogenate (−32.5%) and in mitochondria (−27.9%) (Figure 2A). Consistent with these findings, GSH depletion at 0.5 and 2 h was also significantly inhibited (Figure 2B), suggesting that metformin as a pretreatment moderately inhibited the metabolic activation of APAP. In support of the protection by metformin, GSH recovery was almost 2-fold higher at 24 h in mice with metformin treatment though no significant difference was seen at 6 h (Figure 2B). Interestingly, in contrast to the reduction of JNK activation by metformin reported by Kim et al. (2015), neither JNK activation nor its translocation to mitochondria was affected at 2 or 6 h in our study (Figure 3A and B). Densitometric analysis of these western blots further confirmed these findings (Figure 3C–E). Similar results were obtained using a P-JNK antibody from a different vender, which was used by Kim et al. (2015) (Figure 3F).

FIG. 2.

Metformin slightly inhibited APAP metabolic activation. Mice were treated with 350 mg/kg metformin followed by 400 mg/kg APAP 0.5 h later. A, Total liver and mitochondrial APAP-cysteine adducts at 2 h. B, Time course of hepatic GSH levels in total liver. Bars represent means ± SEM for n = 3–6 mice. *P < .05 compared with 0 h; #P < .05 compared with respective APAP group.

FIG. 3.

Metformin did not inhibit JNK activation or mitochondrial JNK translocation. Mice were treated with 350 mg/kg metformin followed by 400 mg/kg APAP 0.5 h later. Total JNK and P-JNK were measured in cytosolic and mitochondrial liver fractions at 2 h (A) or 6 h (B) post-APAP. Porin was used as loading control for the mitochondrial fraction. Data of densitometric analysis of cytosolic P-JNK/JNK(C), mitochondrial P-JNK/JNK (D) and mitochondrial P-JNK/porin (E) are shown. Cytosolic and mitochondrial P-JNK at 2 h detected by antibody from Santa Cruz (F). Bars represent means ± SEM for 3 mice. *P < .05 compared with control.

Metformin Attenuated APAP-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidant Stress and Dysfunction

Covalent binding of NAPQI to mitochondrial proteins disturbs mitochondrial respiration and causes mitochondrial oxidant stress (Cover et al., 2005; Donnelly et al., 1994; Meyers et al., 1988). GSSG levels and the GSSG-to-total GSH (oxidized + reduced form of glutathione) ratio are excellent indicators of oxidant stress (Jaeschke, 1990). Our data showed that metformin-treated mice had significantly lower GSSG levels at 6 h and a trend to lower GSSG/total GSH at both 6 and 24 h (Figure 4A and B). The lack of lower GSSG levels at 24 h in metformin-treated mice could be due to the fact that these mice had much lower injury and thus consumed more food when the diet was returned at 6 h. This would allow them to better replenish their GSH pool (Figure 2B) and efficiently scavenge ROS, resulting in increased GSSG formation. Consistent with the GSSG data showing protection against oxidant stress by metformin at 6 h, specific measurement of mitochondrial superoxide production, and nitrotyrosine (NT) protein adducts, which are a footprint of peroxynitrite formation, were also substantially reduced in mice with metformin treatment (Figure 4C and D). Overwhelming mitochondrial oxidant stress causes collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential and release of mitochondrial proteins including AIF and Smac to the cytosol and translocation to the nucleus, resulting in nuclear DNA fragmentation (Bajt et al., 2006; Kon et al., 2004). Bax was also shown to translocate to mitochondria and form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane, contributing to the release of mitochondrial intermembrane proteins at the early phase of liver injury (Bajt et al., 2008). Consistent with the previous investigations, in our study we observed Bax translocation to mitochondria at both 2 h and 6 h after APAP (Figure 5A and B). However, metformin did not affect this translocation at either time point (Figure 5A and B). In contrast, the release of mitochondrial proteins such as Smac and AIF was substantially reduced in metformin-treated mice (Figure 5A and B). The corresponding DNA fragmentation was also extensively attenuated (Figure 5C). These data clearly indicate that metformin attenuated the APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress and the subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction.

FIG. 4.

Metformin attenuated APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress. Mice were treated with 350 mg/kg metformin followed by 400 mg/kg APAP 0.5 h later. A, Total liver GSSG levels. B, Hepatic GSSG-to-total GSH ratios. C, MitoSOX fluorescence. D, Nitrotyrosine staining of representative liver sections. Bars represent means ± SEM for n = 3–6 mice. *P < .05 compared with 0 h #P < .05 compared with respective APAP group.

FIG. 5.

Metformin attenuated APAP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Mice were treated with 350 mg/kg metformin followed by 400 mg/kg APAP 0.5 h later. A, Mitochondrial Bax and cytosolic Bax and β-actin at 2 h post-APAP. B, Mitochondrial Bax and AIF and cytosolic Bax, Smac, AIF, and β-actin at 6 h post-APAP. C, TUNEL staining of representative liver sections (6 h).

Posttreatment With Metformin Still Protected Against APAP-Induced Liver Injury

To assess the effect of metformin on APAP-induced liver injury without inhibiting its metabolic activation, metformin was given 2 h post-APAP, at which time the metabolic activation of APAP is almost completed (McGill et al., 2013). Interestingly, metformin still reduced about 50% of the liver injury at 8 h, as indicated by the plasma ALT activities and areas of necrosis in H&E-stained slides (Figure 6A–C). Also, we confirmed that metformin as a 2 h posttreatment did not inhibit APAP metabolic activation, as indicated by similar APAP-protein adducts at both 4 and 8 h (Figure 6D). In addition, neither JNK activation nor mitochondrial translocation was affected, as shown by western blotting (Figure 6E) and confirmed by the densitometric analysis (Figure 6F–H). In contrast, APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress, as assessed by GSSG-to-total GSH ratio (Figure 7A and B) and NT staining (Figure 7C), was reduced in metformin-treated mice. As a result, the release of mitochondrial proteins such as AIF and Smac, as shown by Western blotting (Figure 7D) and quantified by densitometry (Figure 7E), and the resulting DNA fragmentation, as measured by TUNEL staining (Figure 7F), were also largely reduced. Interestingly, there was no evidence that metformin treatment promoted the antioxidant capacity of hepatocytes as none of the relevant enzymes were induced (Table 1). This suggested that metformin did not improve the capacity to scavenge ROS but more likely affected the capacity to generate ROS, as is evident by the direct measurement of mitochondrial superoxide formation (Figure 4C). In support of this, metformin treatment significantly decreased complex I activity in mitochondria from controls and from APAP-treated mice (Figure 8A), and this seemed not due to an effect on protein expression as indicated by the assessment of a complex I subunit (NDUFB8) (Figure 8B). In these animals, there was a strong correlation between complex I activity and liver injury (Figure 8C). Thus, reducing complex I activity by metformin may lower the leakage of electrons from the ETC and therefore contribute to the reduced mitochondrial oxidant stress in metformin-treated mice.

FIG. 6.

Post-treatment with metformin still protected against APAP hepatotoxicity without inhibition of APAP metabolic activation or JNK activation. Mice were treated with 400 mg/kg APAP and 350 mg/kg metformin was given 2 h later. Blood and liver tissue were obtained at 0, 4, or 8 h post-APAP. A, Plasma ALT activities. B, Areas of necrosis (%). C, H&E stained liver sections. D, Total liver APAP-cysteine adducts at 8 h. E, Cytosolic and mitochondrial total JNK and P-JNK at 8 h. Densitometric analysis of cytosolic P-JNK/JNK (F), mitochondrial P-JNK/JNK. (G) and P-JNK/porin (H). Bars represent means ± for n = 3–4 mice. *P<.05 compared with control; #P<.05 compared with respective APAP group.

FIG. 7.

Post-treatment with metformin still protected against APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress and dysfunction. Mice were treated with 400 mg/kg APAP and 350 mg/kg metformin was given 2 h later. Liver tissues were harvested at 8 h post-APAP. A, Total liver GSH levels. B, Hepatic GSSG-to-total GSH ratios. C, Nitrotyrosine staining of representative liver sections. D, Cytosolic Smac, AIF and β-actin measured by western blot and densitometric analysis (E). F, TUNEL staining of representative liver sections. Bars represent means ± SEM for n = 3–4 mice. *P < .05 compared with Ctrl; #P < .05 compared with respective APAP group.

TABLE 1.

Induction of Antioxidant Genes by Acetaminophen and Metformin

| Gene | Ctrl | Met (6 h) | APAP (6 h) | APAP + Met (6 h) | APAP (24 h) | APAP + Met (24 h) | APAP (8 h) | APAP + Met (8 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gclc | 1.10 ± 0.34 | 0.76 ± 0.01 | 2.85 ± 0.48 | 1.80 ± 0.17 | 3.73 ± 0.41* | 3.54 ± 0.29* | 3.83 ± 0.14* | 4.21 ± 0.50* |

| MT-1 | 1.18 ± 0.45 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 8.85 ± 1.17* | 6.20 ± 0.79* | 2.31 ± 0.42 | 3.23 ± 0.52* | 9.73 ± 1.25* | 13.96 ± 0.74*# |

| MT-2 | 1.08 ± 0.26 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 9.26 ± 1.12* | 5.90 ± 0.57* | 1.98 ± 0.37 | 2.87 ± 0.17* | 8.83 ± 1.63* | 12.77 ± 0.65*# |

| NQO1 | 1.04 ± 0.20 | 0.92 ± 0.18 | 1.23 ± 0.21 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 0.44 ± 0.07* | 0.57 ± 0.11* | 1.47 ± 0.03 | 1.76 ± 0.27 |

| Mn-SOD | 1.03 ± 0.17 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.03# |

| HO-1 | 1.06 ± 0.26 | 0.87 ± 0.16 | 49.98 ± 8.15* | 26.42 ± 0.76*# | 19.79 ± 1.67* | 24.24 ± 1.76* | 65.23 ± 7.17* | 58.73 ± 9.13* |

Mice were treated with 400 mg/kg APAP and 350 mg/kg metformin was given 0.5 h before APAP or 2 h after APAP. Liver tissues were harvested at 0 h (Ctrl), 6 or 24 h post-APAP for pretreatment or 8 h for posttreatment. Fold inductions of mRNAs compared with control was expressed as mean ± SE for n = 3–5 mice.

P < .05 compared with Ctrl.

P < .05 compared with APAP.

FIG. 8.

Metformin inhibited mitochondrial complex I activity. Mice were treated with 400 mg/kg APAP and 350 mg/kg metformin was given 2 h later. Mitochondria were isolated from liver tissue at 8 h post-APAP. A, Complex I activity. B, Complex I-NDUFB8 subunit protein expression and corresponding densitometric analysis (n = 3–4 isolations) using porin as the loading control. C, Linear correlation between ALT activity and complex I activity (minus control) in APAP-treated mice. Bars represent means ± SEM for n = 3 (ctrl, met) or n = 4 mice (all APAP-treated groups). *P < .05 compared with Ctrl; #P < .05 compared with APAP group.

Metformin Protected Against APAP-Induced Cell Death in HepRG Cells

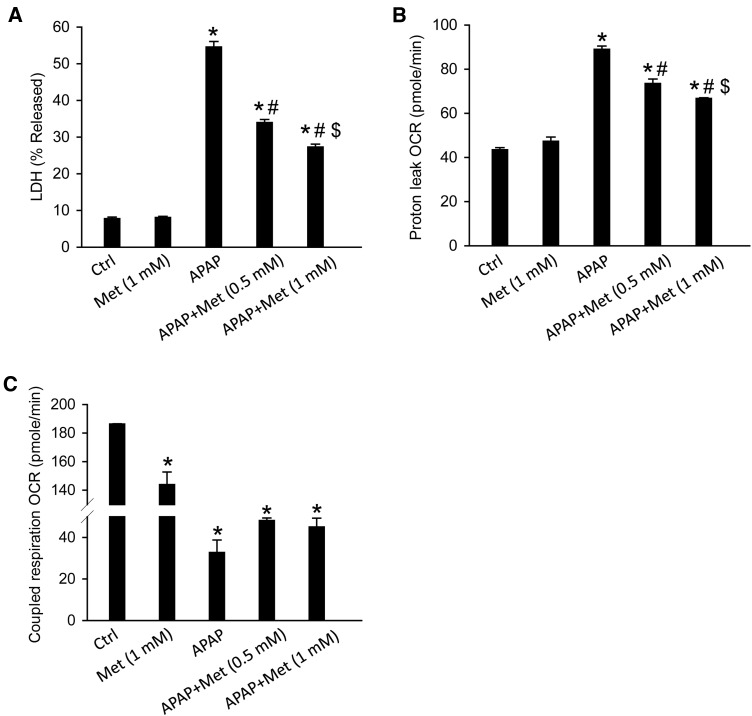

Our data so far indicated that metformin protected against APAP-induced liver injury in mice by a JNK-independent mechanism. To further corroborate our results, we tested the effectiveness of metformin against APAP toxicity in human HepaRG cells. The justification for the use of these cells are 2-fold: (1) they are human cells and would hence closer recapitulate the human condition and (2), whereas these cells show cellular necrosis and mitochondrial oxidant stress in response to APAP as in human patients (McGill et al., 2011), the process is independent of JNK activation (Xie et al., 2014). Thus, if metformin protected against APAP-induced injury in these cells, it would confirm the JNK-independent nature of the effect and also its relevance to humans. HepaRG cells were first treated with 20 mM APAP and metformin was given 6 h post-APAP, at which APAP-protein adducts formation peaks (McGill et al., 2011), to avoid its potential effect on the metabolic activation of APAP. Our data showed that metformin alone (1 mM) did not cause any cell death while APAP (20 mM) resulted in massive cell death at 48 h post-APAP, as indicated by the percentage of LDH release (Figure 9A). More importantly, metformin dose-dependently protected against APAP-induced cell death (Figure 9A), indicating its potential benefit for APAP overdose patients. Interestingly, metformin also significantly decreased the APAP-induced proton leakage from the ETC and increased coupled respiration, which was impaired by APAP (Figure 9B and C). This may decrease the mitochondrial oxidant stress and contribute to the protection.

FIG. 9.

Metformin protected against APAP-induced cell injury in HepaRG cells. The cells were treated with 20 mM APAP and 0.5 or 1 mM metformin was added 6 h post-APAP. Cells were harvested at 48 h for LDH activity measurement (A), or at 24 h for the XF assay: Proton leak (B) and coupled respiration (C). Bars represent means ± SEM for n = 4 independent cell preparations. *P < .05 compared with Ctrl; #P < .05 compared with APAP; $P < .05 compared with APAP + Met (0.5 mM).

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the protective mechanisms of metformin in APAP hepatotoxicity. Our data demonstrated that both pretreatment and posttreatment with metformin protected against APAP hepatotoxicity in mice. The mechanism did not involve inhibition of JNK activation but was caused in part by inhibition of APAP protein adducts formation and mostly by attenuation of the APAP-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction, likely by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I activity.

Role of JNK in APAP Hepatotoxicity

Although controversies and conflicting data exist, most studies argue for a detrimental role of JNK activation in APAP hepatotoxicity, and JNK deficiency or pharmacological inhibition was shown to protect against APAP hepatotoxicity in both mice and primary human hepatocytes (reviewed in Du et al., 2015b). In support of this, metformin was proposed to protect mice against APAP hepatotoxicity by inhibiting JNK activation (Kim et al., 2015). However, careful analysis of the data in this paper raised some serious concerns. Although the authors did not differentiate between the effect of metformin on JNK1 and JNK2, it was obvious that metformin mainly reduced JNK2 activation based on the representative western blots (Kim et al., 2015), whereas the injury induced by APAP was almost completely prevented during this time period (0–5 h). However, previous studies demonstrated that the deficiency of JNK2 alone in mice was only moderately protective at most (Gunawan et al. 2006; Henderson et al., 2007). This leaves the possibility that other protective mechanisms may still exist. Also, the effect of metformin on the metabolic activation of APAP was not fully investigated, which is an important omission that questions the claim for any other downstream protective mechanisms in APAP hepatotoxicity. This is particularly critical when considering the fact that negligence of this issue has led to many misleading conclusions from recent studies investigating the protective mechanisms of drugs and chemicals. In our study, we found that pre-treatment of metformin extensively reduced the injury at both 6 and 24 h. Interestingly, metformin seemed to slightly inhibit metabolic activation of APAP, which is indicated by the moderate inhibition of the early GSH depletion and reduction of APAP-protein adducts formation in both total liver and mitochondria in metformin-treated mice. In contrast to the previous report (Kim et al., 2015), we did not observe any inhibition of JNK activation or mitochondrial JNK translocation by metformin either as a pretreatment or post-treatment. The JNK-independent mechanism of metformin protection in APAP hepatotoxicity was confirmed in HepaRG cells, which recapitulate key mechanisms of toxicity such as protein adducts formation, GSH depletion, oxidant stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and necrotic cell death (McGill et al., 2011), without JNK activation (Xie et al., 2014). The protective effect of metformin in the HepaRG cells, where JNK activation is absent and a JNK inhibitor is not protective (Xie et al., 2014), strongly supports the conclusion that the protective effect of metformin is independent of JNK signaling. We also confirmed this by using the same antibody as acquired by Kim et al. (2015), ruling out the possibility that this discrepancy was due to the different JNK antibodies used. Although elucidating the exact reason for this discrepancy needs further investigation, our studies provide no evidence for JNK as the therapeutic target of metformin.

Metformin Protects Against APAP-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidant Stress and Dysfunction

The APAP hepatotoxicity is characterized by extensive mitochondrial oxidant stress and severe mitochondrial dysfunction (Jaeschke et al., 2012). It is suggested that the reactive metabolite NAPQI binds to mitochondrial proteins, impairs the function of the ETC and causes leakage of electrons and thus results in formation of reactive oxygen species (Donnelly et al., 1994; Jaeschke, 1990). Electrons released from the ETC react with O2 to form superoxide, which can be metabolized by superoxide dismutases (SOD) to form hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen or react with NO to produce peroxynitrite, which is a potent oxidant and nitrating species in APAP hepatotoxicity (Cover et al., 2005; Hinson et al., 1998; Knight et al., 2002). The importance of a mitochondrial oxidant stress in the development of APAP hepatotoxicity has been demonstrated in numerous studies. For example, it was shown that Mn-SOD, the mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme to detoxify O2−, was nitrated and partially inactivated by peroxynitrite after APAP (Agarwal et al., 2011), and mice partial deficient in this enzyme (MnSOD+/−) were more susceptibility to APAP overdose while mice treated with the SOD-mimetic Mito-Tempo were protected from the toxicity (Du et al., 2016; Fujimoto et al., 2009; Ramachandran et al., 2011). In addition, accelerated recovery of hepatic GSH in female mice or by treatment with exogenous GSH or its precursor amino acids decreased mitochondrial oxidant stress and protected against APAP hepatotoxicity (Du et al., 2014; James et al., 2003; Knight et al., 2002; Saito et al., 2010b). Together these reports established the critical role of the mitochondrial oxidant stress in the development of APAP-induced cell death. In our study, we observed that metformin either as a pre-treatment or post-treatment dramatically decreased the mitochondrial oxidant stress, as indicated by the lower GSSG-to-total GSH ratio in the liver, the reduced MitoSOX fluorescent intensity in mitochondria and less nitrotyrosine staining in mice when compared with APAP-treated animals. Interestingly, metformin did not increase the induction of Nrf-2 regulated-antioxidant genes, including gclc, catalase, NQO1, HO-1, and MnSOD (Table 1). It has also been shown that metformin cannot scavenge superoxide radicals and thus is unlikely to engage in direct scavenging activity (Bonnefont-Rousselot et al., 2003; Khouri et al., 2004). Thus, the protective effect of metformin may be due to a decrease in ROS generation, probably by preventing proton leak as seen in HepRG cells, rather than increase in ROS scavenging. Mitochondrial complex I is a crucial site of ROS formation in mitochondria, and can exist in an active or a deactivated form (Grivennikova et al., 2001). Biguanides were shown to selectively “lock” complex I in its deactivated form leading to decreased superoxide production capacity (Matsuzaki and Humphries, 2015). In rats fed a high fat diet, metformin was shown to protect against hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibiting complex I and lowering mitochondrial ROS production (Cahova et al., 2015). In various cell culture models, metformin was reported to inhibit complex I activity, mitochondrial permeability transition and cell death (Bridges et al., 2014; Drahota et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2015). Consistent with these reports, our study showed that metformin inhibited complex I activity and decreased mitochondrial superoxide production, which prevents mitochondrial oxidant stress and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction, as measured by the inhibition of mitochondrial protein release (AIF and Smac) and reduction in nuclear DNA fragmentation. It is interesting that metformin treatment prevented AIF release, whereas having no effect on JNK activation, even though AIF-deficient Harlequin mice were protected from APAP hepatotoxicity with reduced mitochondrial oxidant stress and less JNK activation (Bajt et al., 2011). However, these results are caused by different mechanisms. In the current experiment, AIF release mainly is caused by mitochondrial dysfunction (MPT) and matrix swelling; in the previous experiments, the reduced JNK activation in AIF-deficient Harlequin reflects the physiological role of AIF in regulating leakage of electrons from the ETC (Bajt et al., 2011).

Metformin as a Potential Therapeutic Agent for APAP Overdose

The NAC was introduced as the clinical antidote for APAP poisoning in the late 1970s (Prescott et al., 1977), and even today it is still the only available therapeutic agent in the clinic. However, NAC has to be given early (before injury is present) to achieve its greatest efficacy. Unfortunately, in clinical practice, many patients arrive relatively late for medical care after taking an overdose of APAP (around or after the peak of injury) (Larson, 2007; Xie et al., 2015). At this later time point, the efficacy of NAC is significantly diminished (Smilkstein et al., 1988). Actually, NAC is only highly effective up to 2 h after APAP in mice and within 8 h of APAP ingestion in patients (before initiation of injury) (Knight et al., 2002; Smilkstein et al., 1988). Therefore, an intervention that is still beneficial after the onset of the injury is needed. However, due to the high costs of drug development, even late acting drugs may not be developed for human use. In contrast, metformin as a marketed drug has a higher potential to be used in a clinical trial. We demonstrated that metformin given as late as 2 h after APAP overdose in mice still reduced approximately 50% of the injury at 8 and 24 h. Whether metformin is still beneficial beyond 2 h post-APAP requires further experiments. In addition, a comparison of the protection by NAC to that by metformin, as well as an evaluation of their potential synergistic effects is needed to further test the feasibility of metformin as a therapeutic agent for overdose patients. Interestingly, human HepaRG cells treated with metformin 6 h after APAP, at the time when the metabolic activation of APAP is almost completed and cell injury is in development, are still dose-dependently protected from APAP-induced cell injury. Because the HepaRG cell model has been shown to closely resemble the human pathophysiology for APAP overdose (McGill et al., 2011), it also strongly supports the potential effectiveness of metformin for patients with APAP overdose.

A caveat for the clinical use of metformin, however, is the reported increase in incidences of lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients according to some case reports and its contraindication in patients with liver disease (Brackett 2010). However, these instances are uncommon (9/100 000 person-years) and not different from that in the general population (Stang et al., 1999). A systematic review also concluded that no data exist to definitively link metformin to lactic acidosis (Salpeter et al., 2003) and the beneficial effect of metformin on varied liver diseases have been noted (Bhat et al., 2015). None of the attributed side effects of metformin such as diarrhea, kidney injury, or liver toxicity were noted in the mice at the dose we used (data not shown) and neither was any cell injury evident from metformin alone in HepRG cells. Nevertheless, before metformin can be considered as a realistic antidote against APAP hepatotoxicity in patients, studies need to assess the effective therapeutic dose in humans and any potential side effects of this new treatment after APAP overdose.

Summary and Conclusions

We showed that metformin did not inhibit JNK activation or mitochondrial JNK translocation but significantly reduced APAP protein adducts formation in mitochondria and in particular attenuated the mitochondrial oxidant stress and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction, most likely through inhibition of mitochondrial complex I activity. In addition, metformin dose-dependently protected human HepaRG cells, a clinically relevant model for APAP overdose, against APAP-induced cell injury, supporting metformin as a potential therapeutic option for the treatment of APAP overdose-induced acute liver failure in patients.

FUNDING

This investigation was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK102142 and R01 AA12916, and by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR021940-07) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P20 GM103549-07) from the National Institutes of Health. Additional support came from an award from the Biomedical Research Training Program (BRTP) from the University of Kansas Medical Center (to K.D.).

REFERENCES

- Agarwal R., MacMillan-Crow L. A., Rafferty T. M., Saba H., Roberts D. W., Fifer E. K., James L. P., Hinson J. A. (2011). Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice occurs with inhibition of activity and nitration of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 337, 110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt M. L., Cover C., Lemasters J. J., Jaeschke H. (2006). Nuclear translocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor during acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 94, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt M. L., Farhood A., Lemasters J. J., Jaeschke H. (2008). Mitochondrial bax translocation accelerates DNA fragmentation and cell necrosis in a murine model of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt M. L., Knight T. R., Lemasters J. J., Jaeschke H. (2004). Acetaminophen-induced oxidant stress and cell injury in cultured mouse hepatocytes: protection by N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol. Sci. 80, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt M. L., Lawson J. A., Vonderfecht S. L., Gujral J. S., Jaeschke H. (2000). Protection against Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells by a caspase-8 inhibitor in vivo: evidence for a postmitochondrial processing of caspase-8. Toxicol. Sci. 58, 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt M. L., Ramachandran A., Yan H. M., Lebofsky M., Farhood A., Lemasters J. J., Jaeschke H. (2011). Apoptosis-inducing factor modulates mitochondrial oxidant stress in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 122, 599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A., Sebastiani G., Bhat M. (2015). Systematic review: Preventive and therapeutic applications of metformin in liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 7, 1652–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefont-Rousselot D., Raji B., Walrand S., Gardès-Albert M., Jore D., Legrand A., Peynet J., Vasson M. P. (2003). An intracellular modulation of free radical production could contribute to the beneficial effects of metformin towards oxidative stress. Metabolism 52, 586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackett C. C. (2010). Clarifying metformin's role and risks in liver dysfunction. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 50, 407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges H. R., Jones A. J., Pollak M. N., Hirst J. (2014). Effects of metformin and other biguanides on oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. Biochem. J. 462, 475–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnitz D. S., Lovegrove M. C., Crosby A. E. (2011). Emergency department visits for overdoses of acetaminophen-containing products. Am. J. Prev. Med. 40, 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahova M., Palenickova E., Dankova H., Sticova E., Burian M., Drahota Z., Cervinkova Z., Kucera O., Gladkova C., Stopka P., and., et al. (2015). Metformin prevents ischemia reperfusion-induced oxidative stress in the fatty liver by attenuation of reactive oxygen species formation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 309, G100–G111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover C., Mansouri A., Knight T. R., Bajt M. L., Lemasters J. J., Pessayre D., Jaeschke H. (2005). Peroxynitrite-induced mitochondrial and endonuclease-mediated nuclear DNA damage in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315, 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly P. J., Walker R. M., Racz W. J. (1994). Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration in vivo is an early event in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 68, 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota Z., Palenickova E., Endlicher R., Milerova M., Brejchova J., Vosahlikova M., Svoboda P., Kazdova L., Kalous M., Cervinkova Z., et al. (2014). Biguanides inhibit complex I, II and IV of rat liver mitochondria and modify their functional properties. Physiol. Res. 63, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K., Farhood A., Jaeschke H. (2016). Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mito-Tempo protects against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Arch. Toxicol. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K., McGill M. R., Xie Y., Jaeschke H. (2015a). Benzyl alcohol protects against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzymes but causes mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death at higher doses. Food Chem. Toxicol. 86, 253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K., Williams C. D., McGill M. R., Jaeschke H. (2014). Lower susceptibility of female mice to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: Role of mitochondrial glutathione, oxidant stress and c-jun N-terminal kinase. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 281, 58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K., Williams C. D., McGill M. R., Xie Y., Farhood A., Vinken M., Jaeschke H. (2013). The gap junction inhibitor 2-aminoethoxy-diphenyl-borate protects against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzymes and c-jun N-terminal kinase activation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 273, 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K., Xie Y., McGill M. R., Jaeschke H. (2015b). Pathophysiological significance of c-jun N-terminal kinase in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 11, 1769–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K., Kumagai K., Ito K., Arakawa S., Ando Y., Oda S., Yamoto T., Manabe S. (2009). Sensitivity of liver injury in heterozygous Sod2 knockout mice treated with troglitazone or acetaminophen. Toxicol. Pathol. 37, 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikova V. G., Kapustin A. N., Vinogradov A. D. (2001). Catalytic activity of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in intact mitochondria. Evidence for the slow active/inactive transition. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9038–9044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral J. S., Knight T. R., Farhood A., Bajt M. L., Jaeschke H. (2002). Mode of cell death after acetaminophen overdose in mice: Apoptosis or oncotic necrosis? Toxicol. Sci. 67, 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan B. K., Liu Z. X., Han D., Hanawa N., Gaarde W. A., Kaplowitz N. (2006). c-Jun N-terminal kinase plays a major role in murine acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Gastroenterology 131, 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa N., Shinohara M., Saberi B., Gaarde W. A., Han D., Kaplowitz N. (2008). Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13565–13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson N. C., Pollock K. J., Frew J., Mackinnon A. C., Flavell R. A., Davis R. J., Sethi T., Simpson K. J. (2007). Critical role of c-jun (NH2) terminal kinase in paracetamol-induced acute liver failure. Gut 56, 982–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson J. A., Pike S. L., Pumford N. R., Mayeux P. R. (1998). Nitrotyrosine-protein adducts in hepatic centrilobular areas following toxic doses of acetaminophen in mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 11, 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H. (1990). Glutathione disulfide formation and oxidant stress during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice in vivo: The protective effect of allopurinol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 255, 935–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H., McGill M. R., Ramachandran A. (2012). Oxidant stress, mitochondria, and cell death mechanisms in drug-induced liver injury: Lessons learned from acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab. Rev. 44, 88–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H., Mitchell J. R. (1990). Use of isolated perfused organs in hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion oxidant stress. Methods Enzymol. 186, 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James L. P., McCullough S. S., Lamps L. W., Hinson J. A. (2003). Effect of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen toxicity in mice: Relationship to reactive nitrogen and cytokine formation. Toxicol. Sci. 75, 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen A. J., Trijbels F. J., Sengers R. C., Smeitink J. A., van den Heuvel L. P., Wintjes L. T., Stoltenborg-Hogenkamp B. J., Rodenburg R. J. (2007). Spectrophotometric assay for complex I of the respiratory chain in tissue samples and cultured fibroblasts. Clin. Chem. 53, 729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson‐Cadwell L. I., Jekabsons M. B., Wang A., Polster B. M., Nicholls D. G. (2007). Mild Uncoupling’ does not decrease mitochondrial superoxide levels in cultured cerebellar granule neurons but decreases spare respiratory capacity and increases toxicity to glutamate and oxidative stress. J. Neurochem. 101, 1619–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B., Tannahill G. M., Murphy M. P., O'Neill L. A. (2015). Metformin inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species from NADH: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase to limit induction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and boosts interleukin-10 (IL-10) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 20348–20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouri H., Collin F., Bonnefont-Rousselot D., Legrand A., Jore D., Gardès-Albert M. (2004). Radical-induced oxidation of metformin. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 4745–4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. H., Hwang J. H., Kim K. S., Noh J. R., Choi D. H., Kim D. K., Tadi S., Yim Y. H., Choi H. S., Lee C. H. (2015). Metformin ameliorates acetaminophen hepatotoxicity via Gadd45β-dependent regulation of JNK signaling in mice. J. Hepatol. 63, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight T. R., Ho Y. S., Farhood A., Jaeschke H. (2002). Peroxynitrite is a critical mediator of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in murine livers: protection by glutathione. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 303, 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K., Kim J. S., Jaeschke H., Lemasters J. J. (2004). Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology 40, 1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson A. M. (2007). Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Clin. Liver Dis. 11, 525–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthripragada A. D., Zhou E. H., Budnitz D. S., Lovegrove M. C., Willy M. E. (2011). Characterization of acetaminophen overdose-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 20, 819–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki S., Humphries K. M. (2015). Selective inhibition of deactivated mitochondrial complex I by biguanides. Biochemistry 54, 2011–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M. R., Jaeschke H. (2015). A direct comparison of methods used to measure oxidized glutathione in biological samples: 2-vinylpyridine and N-ethylmaleimide. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 25, 589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M. R., Lebofsky M., Norris H. R., Slawson M. H., Bajt M. L., Xie Y., Williams C. D., Wilkins D. G., Rollins D. E., Jaeschke H. (2013). Plasma and liver acetaminophen-protein adduct levels in mice after acetaminophen treatment: Dose-response, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 269, 240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M. R., Williams C. D., Xie Y., Ramachandran A., Jaeschke H. (2012). Acetaminophen-induced liver injury in rats and mice: comparison of protein adducts, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in the mechanism of toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 264, 387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M. R., Yan H. M., Ramachandran A., Murray G. J., Rollins D. E., Jaeschke H. (2011). HepaRG cells: A human model to study mechanisms of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Hepatology 53, 974–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers L. L., Beierschmitt W. P., Khairallah E. A., Cohen S. D. (1988). Acetaminophen-induced inhibition of hepatic mitochondrial respiration in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 93, 378–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. R., Jollow D. J., Potter W. Z., Davis D. C., Gillette J. R., Brodie B. B. (1973). Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. I. Role of drug metabolism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 187, 185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S. D. (1990). Molecular mechanisms of the hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen. Semin. Liver Dis. 10, 267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H. M., Boggess N., McGill M. R., Lebofsky M., Borude P., Apte U., Jaeschke H., Ding W. X. (2012). Liver-specific loss of Atg5 causes persistent activation of Nrf2 and protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 127, 438–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott L. F., Park J., Ballantyne A., Adriaenssens P., Proudfoot A. T. (1977). Treatment of paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning with N-acetylcysteine. Lancet 27, 432–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A., Lebofsky M., Weinman S. A., Jaeschke H. (2011). The impact of partial manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2)-deficiency on mitochondrial oxidant stress, DNA fragmentation and liver injury during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 251, 226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C., Lemasters J. J., Jaeschke H. (2010a). c-Jun N-terminal kinase modulates oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation independent of inducible nitric oxide synthase in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 246, 8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C., Zwingmann C., Jaeschke H. (2010b). Novel mechanisms of protection against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Hepatology 51, 246–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salpeter S. R., Greyber E., Pasternak G. A., Salpeter E. E. (2003). Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 163, 2594–2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein M. J., Knapp G. L., Kulig K. W., Rumack B. H. (1988). Efficacy of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. Analysis of the national multicenter study (1976 to 1985). N. Engl. J. Med. 319, 1557–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang M., Wysowski D. K., Butler-Jones D. (1999). Incidence of lactic acidosis in metformin users. Diabetes Care 22, 925–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., McGill M. R., Cook S. F., Sharpe M. R., Winefield R. D., Wilkins D. G., Rollins D. E., Jaeschke H. (2015). Time course of acetaminophen-protein adducts and acetaminophen metabolites in circulation of overdose patients and in HepaRG cells. Xenobiotica 45, 921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., McGill M. R., Dorko K., Kumer S. C., Schmitt T. M., Forster J., Jaeschke H. (2014). Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced cell death in primary human hepatocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 279, 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Williams C. D., McGill M. R., Lebofsky M., Ramachandran A., Jaeschke H. (2013). Purinergic receptor antagonist A438079 protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury by inhibiting p450 isoenzymes, not by inflammasome activation. Toxicol. Sci. 131, 325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]