Abstract

The increasing demand for behavior analytic services and the number of individuals pursuing credentials to provide these services evoke questions regarding certification and how the requirements for becoming a Board Certified Behavior Analyst® (BCBA®) compare with those for other professions. In this paper, we compared licensure and board certification requirements across similar behavioral health professions (i.e., behavior analysis, clinical social work, educational psychology, marriage and family therapy, and clinical psychology) and found that the minimum requirements for certification of behavior analysts were commensurate. We discuss the implications of our comparisons for practitioners, consumers, and the field and offer some recommendations for future consideration.

Keywords: BCBA, board certification, board standards, credentials, licensure

HIGHLIGHTS.

As with any profession, the reputation of the BCBA credential is influenced by the ethics and professional competence of the credentialed individuals delivering services and by the continued effectiveness of such services.

Is the BCBA an appropriate basis for licensure of practitioners who provide ABA services?

We compared the BCBA credential to well-known licensures in similar behavioral health professions.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that the degree and educational requirements for certification of behavior analysts are commensurate to board standards for licensure of other behavioral health professionals.

We recommend that future research focus on measuring the effectiveness of current board requirements in producing competent behavior analysts.

Services based on applied behavior analysis (ABA) and certified practitioners of ABA are in high demand because of the well-documented effectiveness of behavior analytic interventions (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001; Eldevik et al., 2009). The field is burgeoning as evidenced by the recent development of the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts in 2007 and Behavior Analysis in Practice in 2008, a peer-reviewed journal specifically formed to meet the needs of practitioners. The increasing demand for ABA services has increased pressures on policymakers to recognize ABA practitioners in state laws and regulations and to move toward licensing them to protect the safety of consumers (Dorsey, Weinberg, Zane, & Guidi, 2009; Green & Johnston, 2009a). Therefore, it is important for behavior analysts to consider how stakeholders such as legislatures, insurers, and consumers view Board Certified Behavior Analysts® (BCBAs®) and the factors that affect the social acceptability of the BCBA credential.

The credentialing of practitioners is relatively new in the history of behavior analysis (Shook & Favell, 2008). Stakeholders are likely more familiar with credentialed and long-standing behavioral health professions and need a means for professional comparisons to identify whether the BCBA is an appropriate basis for licensure of practitioners of ABA. As with any profession, the reputation of the BCBA credential is influenced by the ethics and professional competence of the credentialed individuals delivering services and by the continued effectiveness of such services (Johnson & Shook, 1987; Shook, 1993; Shook & Favell, 2008; Shook & Neisworth, 2005; Shook & Van Houten, 1993). Moreover, without knowledge of the competencies required in each behavioral health profession, the public is likely to assess the legitimacy of any new credential by comparing the more obvious, cursory dimensions (e.g., duration of training and total number of supervised experience hours) of the new credential to existing, trusted credentials.

The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to determine how the BCBA compares to minimum board requirements to obtain the credentials of other behavioral health professionals. We selected licensed clinical social workers, licensed educational psychologists, licensed marriage and family therapists, and licensed psychologists as comparison professions. Although the guiding philosophy and scopes of practice of these professionals differ, they are similar in that they all work independently or with multidisciplinary teams, conduct assessments, and offer clinical treatments to mitigate behavioral problems and improve individuals' lives. Furthermore, each of the selected professions works with at-risk populations and their families, provides parent and caregiver training, has influential roles in clients' life outcomes, and does not prescribe pharmacological interventions. However, unlike the BCBA, these professions are licensed, consistently recognized by insurers, and have a longer history with credentialing boards. Licenses are issued and monitored at the state level; therefore, the minimum board requirements for licensure differ across states. To compare the credentials feasibly and methodically, we provided a brief history of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB®), discussed the differences between certification and licensure, and outlined the requirements for the three states in which the highest number of BCBAs resided (i.e., California [CA], Florida [FL], and Massachusetts [MA]). These three states account for almost a half (i.e., 47%) of the BCBAs nationwide (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2012).

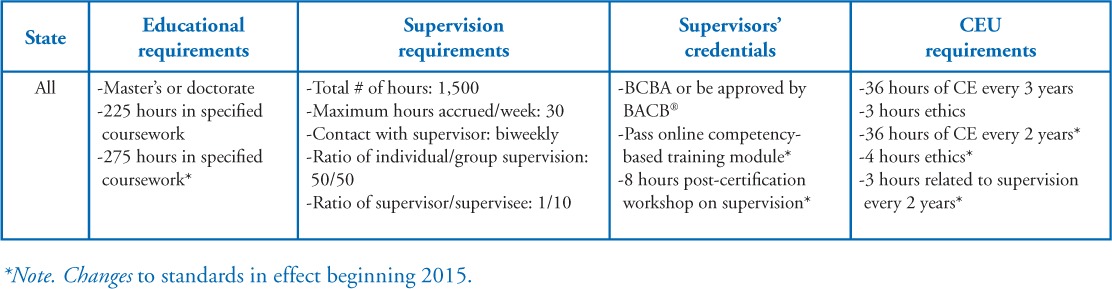

To compare the licensure requirements across states, we collected information from each jurisdiction and outlined: (a) educational requirements, (b) supervision requirements, (c) supervisors' credentials, and (d) continued education units (CEU) requirements. In line with other researchers (Crane et al., 2010; DiLillo, DeGue, Cohen, & Morgan, 2006; Hartley, Ziller, Lambert, Loux, & Bird, 2002), who outlined licensure requirements for other behavioral health professions, we obtained the majority of the information by conducting web-based searches of state board and legislative websites. When statutes and requirements pertaining to licensure were unclear, we emailed or phoned state boards and associations for further clarification and referenced the personal communication if they responded to our queries. We collected these data over the course of 10 months between March 2012 and January 2013. The data we report here are as of January 2013 with the exception of the new standards by BACB, which were released in the February 2013 BACB Newsletter. For detailed information regarding credential requirements, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Certification Requirements for BCBAs

The BCBA Credential

Background and history. Although ABA has been established for several decades, with solid empirical foundations in experimental analysis of behavior since 1958 and in applied research since 1968, the BACB® credentialing program has been in existence for just over a decade. In the early 1970s, a panel sponsored by the Florida State Health and Rehabilitative Services Division of Retardation was created to address several charges of horrific resident abuse at the Sunland Training Center in Miami. One of the goals of the Blue Ribbon Panel was to prevent future abuse by unqualified, poorly trained individuals. Some of the recommendations made by the panel (two of whom were behavior analysts Jack May and Todd Risley) were the establishment of strict guidelines for behavioral treatment and an infrastructure for oversight and supervision by properly trained professionals. Consequently, in the 1980s, the Division of Retardation sponsored the Statewide Peer Review Committee (PRC) for Behavior Modification in conjunction with the newly formed Florida Association for Behavior Analysis (FABA) to certify behavior analysts who passed an examination of professional standards (see Bailey & Burch, 2011 for more detail). The BACB was officially established in 1998 and was based on the successful certification program developed by the state of Florida and similar programs established in California, Texas, Pennsylvania, New York, and Oklahoma (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2013b). All state credentialing programs ceased operations subsequently and transferred all certification responsibilities to BACB. In August 2007, the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA) accredited the credentialing programs of the BACB. To adhere to the national standards for boards, the BACB continues to conduct job analysis surveys and invite content experts in the field of behavior analysis to establish professional standards.

Board certification versus licensure. Certification and licensure are similar in that both are designed to protect the consumers as well as the professionals who hold the credential. All legitimate credentialing programs are managed by independent nonprofit organizations or boards and have the following features in common: (a) require passage of professional examinations that are psychometrically valid, reliable, and administered with tight security, usually by an objective third party; (b) require completion of minimum criteria to become eligible to sit for the exam (which may include degree[s] from accredited educational institutions, specified coursework in the subject matter, and specified amount and type of experiential training); (c) require continuing education for maintaining the credential; (d) have ethical and disciplinary standards and enforcement procedures; (e) provide due process protections; and (f) utilize systematic, empirical procedures for conducting a job analysis (Green, 2011).

Although they have several essential features in common, certification and licensure differ in the extent to which they regulate and restrict practice. Certification programs are guild organizations operated by professional organizations or nonprofit boards that are affiliated with the professional organization, whereas licensure is operated by governmental entity (e.g., state) under authority of a law. Certification may or may not be required to practice a profession but licensure restricts the practice and even the title of a profession to individuals who meet the state's requirements, which typically are set by the state and incorporate standards established by national credentialing bodies or professional organizations (Green, 2011). Unlike certification, state boards can, and often do, require specific examinations on state laws, regulations, and standards as part of the licensing process. Lastly, a state board of licensure has the staff and legal authority to respond to legal complaints by the general public or professionals regarding unethical conduct by licensed individuals. However, certification boards, especially a national organization such as the BACB, will not review complaints until local agencies have investigated and ruled on the case and may not have the resources for such an intensive process (Dorsey et al., 2009). For example, the BACB Guidelines for Responsible Conduct for Behavior Analysts serves as a resource for consumers and professionals and may be referenced in complaints alleging violation of BACB's Disciplinary and Ethical Standards; however, the Guidelines are not independently enforced (see Dorsey et al., 2009 for a more thorough rationale for establishing licensing standards for behavior analysts on a state-by-state basis).

In sum, the BACB is more akin to other national certification boards that set the professional standards, administer the national professional examination, and are recognized in state licensure. The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), for example, has been credentialing qualified school psychologists since 1988, and presently 30 states use the NASP credentialing requirement as a part of their standard for state certification (NASP, n.d., States Aligning Credentialing Requirements with the NCSP and NASP Graduate Preparation Standards). However, board certification in other professions typically is developed after licensure standards have been developed through individual state licensing boards (Dorsey et al., 2009). Board certification in medicine and psychology, for example, typically denote a specialty in the profession or achievement of standards above and beyond the state licensure. The board certification may provide the credentialed individuals with additional recognition and benefits such as the right to practice across states and some licensing boards accept the board certification as the basis for their licensing. Thus, in this paper we compared the BCBA credential to well-known licensures in similar behavioral health professions because the BACB was established before state licensing boards for credentialing of behavior analysts.

Overview of State Licensing Board Standards for Each Profession

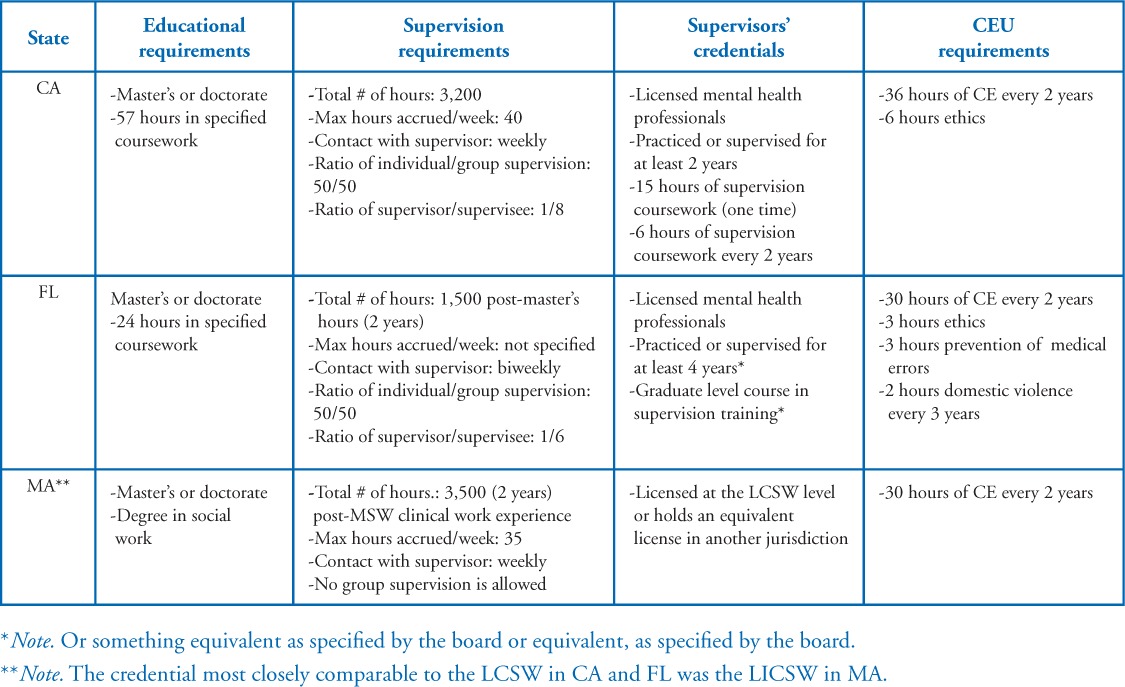

Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW). The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) defines LCSWs as individuals who apply “social work values, principles, and techniques to one or more of the following ends: helping people obtain tangible services; counseling and psychotherapy with individuals, families, and groups; helping communities or groups provide or improve social and health services; and participating in legislative processes” (n.d., “Practice,” para. 1). California was the first state to offer the clinical social worker license in 1950 through the state Board of Behavioral Sciences (see NASW, 1995). According to the Clinical Social Work Association (2008), there are an estimated 300,000 LCSWs in the United States. To obtain this license, most states require that individuals earn, at minimum, a master's degree in social work or in a related field from an accredited or approved university (Hartley et al., 2002); 2% of LCSWs have a doctoral degree (Center for Health Workforce Studies School of Public Health & NASW Center for Workforce Studies, 2004). State requirements regarding supervision experience most frequently include no less than two years of post-degree specified clinical experience, and no more than half of the supervised hours accrued can occur in a group setting (Hartley et al., 2002). For detailed information regarding credential requirements in CA, FL, and MA, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Licensing Requirements for LCSWs

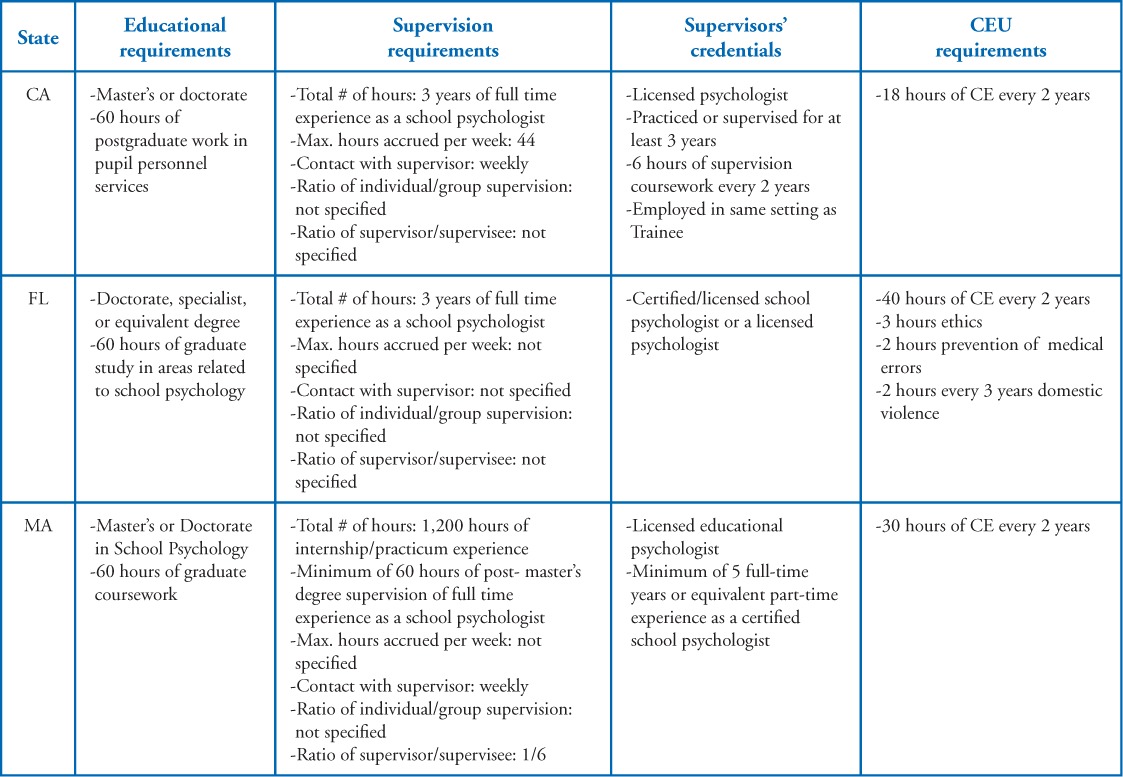

Licensed Educational Psychologist (LEP). The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) defines LEPs as individuals who “help children and youth succeed academically, socially, behaviorally, and emotionally while collaborating with educators, parents, and other professionals to create safe, healthy, and supportive learning environments that strengthen connections between home, school, and the community for all students” (n.d., What is a school psychologist, para. 1). New York and Pennsylvania began to regulate school psychology practice in the late 1940s (Flanagan & Miller, 2010). According to NASP (2008), there are approximately 35,400 LEPs in the United States. To obtain this license, most states require that individuals earn, at minimum, a specialist-level graduate degree (i.e., 60+ semester hours according to NASP, 2006), while some require a doctorate. Approximately 30% of LEPs have a doctorate in psychology, educational psychology, school psychology, counseling and guidance, or from a program deemed equivalent by the board (Curtis, Grier, & Hunley, 2004). State requirements regarding supervision experience most frequently, include no less than three years of specified clinical experience. For detailed information regarding credential requirements in CA, FL, and MA, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Licensing Requirements for LEPs

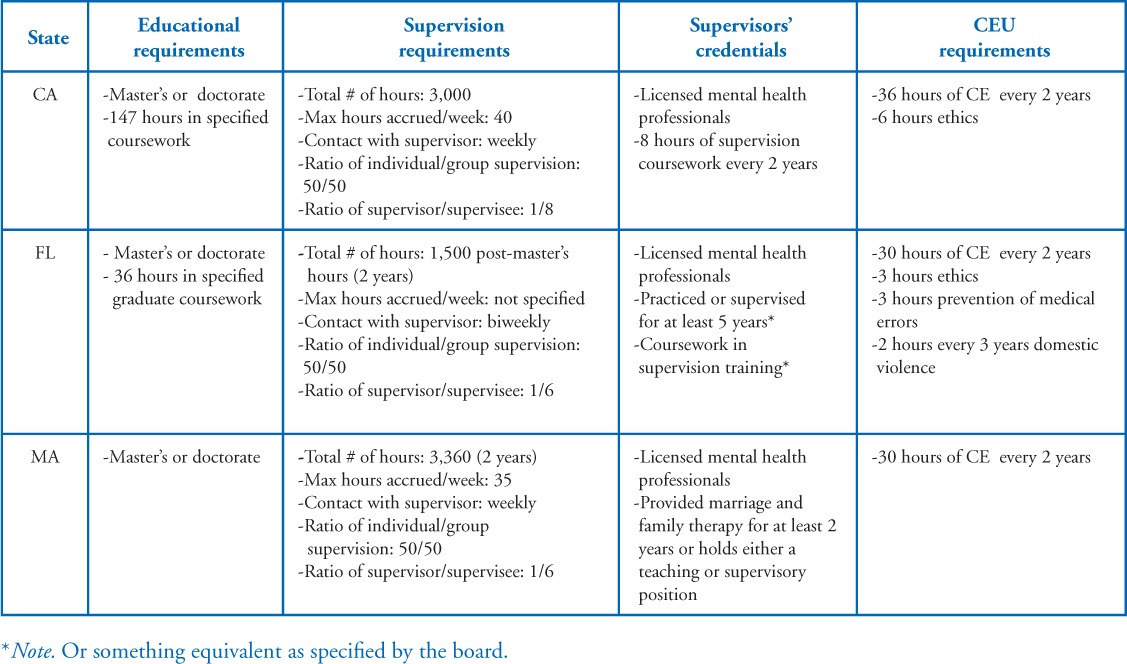

Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT). The American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) defines LMFTs as mental health professionals “trained in psychotherapy and family systems and licensed to diagnose and treat mental and emotional disorders within the context of marriage, couples and family systems” (2011c, para. 2). California was the first state to offer the MFT license in 1963 through the state Board of Behavioral Sciences (California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists, 2012). According to the AAMFT (2011b), there are an estimated 47,439 LMFTs in the United States. To obtain this license, most states require that individuals have earned, at minimum, a master's degree in marriage and family therapy or in a related field from an accredited or approved university, and 30% of all MFTs have a doctoral degree (AAMFT, 2011a). Similar to LCSWs, state requirements regarding supervision experience most frequently include no less than 2 years of post-degree specified clinical experience, and no more than half of the supervised hours accrued can occur in a group setting (Hartley et al., 2002). For detailed information regarding credential requirements in CA, FL, and MA, see Table 4.

Table 4.

Licensing Requirements for LMFTs

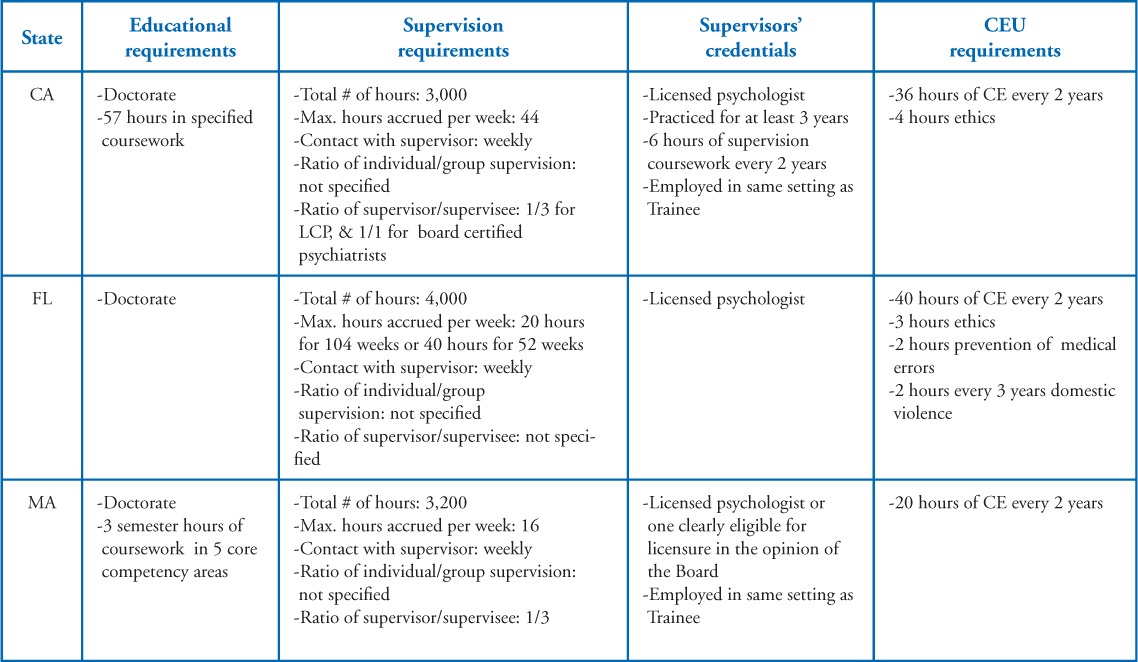

Licensed Psychologist (LP). The American Board of Clinical Psychology (ABCP) defines LPs as mental health professionals who “provide professional services relating to the diagnosis, assessment, evaluation, treatment and prevention of psychological, emotional, psychophysiological, and behavioral disorders in individuals across the lifespan” (American Board of Professional Psychology, n.d., para. 2). Connecticut became the first state to license psychologists in 1945 through the state Department of Public Health Board of Examiners of Psychologists (Robiner, 2006). According to the Riley Guide (2011), there are an estimated 152,000 LPs in the United States. To obtain this license, almost all states require that individuals earn a minimum of a doctorate in clinical or counseling psychology from an accredited or approved university (Hartley et al., 2002). State requirements regarding supervision experience most frequently, include no less than 2 years of specified clinical experience (1 year post-doctorate) and no more than half of the supervised hours accrued can occur in a group setting (Hartley et al., 2002). For detailed information regarding credential requirements in CA, FL, and MA, see Table 5.

Table 5.

Licensing Requirements for LPs

Summary of Minimum Requirements for Licensure Across Professions

For a majority of the behavioral health professions, minimal educational requirements include a master's degree in the particular profession or a field deemed equivalent by the board. Most educational requirements include a specified number of classroom training hours in particular content areas outlined by the board or an accrediting body. One noted exception is the LP credential; individuals seeking this credential are required to obtain a doctorate to practice independently. Supervision requirements are similar across all professions and include some supervised clinical experience (i.e., minimum 1,200 total experience hours) prior to licensure. However, requirements regarding the credentials of the supervisor and the number of hours required in face-to-face consultation are heterogeneous across states (Hartley et al., 2002). For example, most licensing boards' minimum requirements to supervise a trainee include holding an active license as a mental health professional for a specified number of years, but some states additionally require that the supervisor complete a specified number of hours of supervision training or coursework. In regards to CE units, most of the boards we reviewed require a specified number of CE hours every 2 years. Some boards stipulate that a portion of the CE hours must cover topics such as ethics, prevention of medical errors, or domestic violence. For all states and professions, to obtain licensure, individuals must pass a criterion-based multiple-choice national licensure examination and a state supplemental examination (e.g., Jurisprudence Examination in Massachusetts or the Psychology Supplemental Examination in California) that differs from the national board examinations in that they specifically cover state laws and practice standards (Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation, 2013; PSYCHPREP, 2011).

Where Does the BCBA Stand in Relation to the Mentioned Licenses?

In our review, we found that BACB's requirements have changed dramatically over the past few years (and several more changes are expected to be in effect by 2015) as the credential becomes more established. Since its formal inception, the BACB has gradually increased certification standards. For example, there was an increase in the BCBA coursework from a total of 180 to 225 contact hours in 2005 and there is another 45 hour increase that will be implemented by 2015 (Shook, 2005;“An Upcoming BACB® Initiative,” 2011). With the recent proposed requirements, the degree and educational requirements for certification of behavior analysts are commensurate to board standards for licensure of other behavioral health professionals (see Tables 1–5). Similar to other behavioral health professionals, BCBA candidates are required to possess a minimum of a master's degree in a related field and to complete specified hours of course-work directly related to ethics and the science and practice of behavior analysis. Specifically, BCBA candidates must possess a master's degree in behavior analysis or in other natural science, education, human services, engineering, medicine, or a field related to behavior analysis and approved by BACB. As of December 31, 2015, candidates will have to possess “a master's degree from an accredited university that was (a) conferred in behavior analysis, education, or psychology, or (b) conferred in a degree program in which the candidate completed a BACB® approved course-series” (2013c, para. 2). Additionally, BCBA candidates will be required to complete 225 specified classroom hours (270 hours by 2015), either during or following their graduate degree.

We found that the experience requirements for certification of behavior analysts are incommensurate to the board standards for licensure of other behavioral health professionals. However, with the recently proposed BACB requirements for supervised experience (2013c) the BCBA credential will be more in line with the experience requirements of other professions by the year 2015. All credentialing boards require documented supervised experience hours; however, the total number and the duration of hours vary considerably across credentials (e.g., total number of hours range from 1,200 to 3,500). Although the BACB does not require a specific number of pre – versus post-degree experience hours, requirements regarding the nature of the supervisory contact, the duration of experience hours, and the supervisors' credentials are similar to the requirements of other behavioral health professions. The BACB accepts three categories of supervised experience: Supervised Independent Fieldwork, Practicum, and Intensive Practicum. The categories differ in total number of hours based on the specified intensity of supervision. To facilitate comparisons between professions, we will only outline the BACB requirements for the Independent Fieldwork.

At first glance, the number of supervised hours (i.e., 1,500 for Independent Fieldwork) may not seem comparable to other behavior health professions. However, to discourage documentation of hours that are administrative and not behavior analytic in nature, the BACB allows candidates to accrue a maximum of 30 hours of work per week (compared to 40 or 44 hours per week accrued by most other master's level credentials). Therefore, similar to other professions, BCBA candidates accruing experience hours full-time are likely to complete their hours in about 2 years. Concerning the nature of supervisory contact, the BACB requires that supervision occur at least biweekly, that there is individual contact with the supervisor for at least 50% of the supervision hours, and that the supervisor/supervisee ratio during group supervision does not exceed one supervisor per ten supervisees. We found that the ratio of supervisors to supervisees typically is lower in most other behavior health professions such that one supervisor oversees no more than six supervisees.

Currently, the BACB's requirements regarding who can supervise BCBA candidates is not on par with other behavior health professions such that potential supervisors need only to possess their BCBA and be in good standing with the board. Across most other professions and states, however, the requirements to supervise interns include a minimum of at least a specified number of years of practice, or supervision experience, or something deemed equivalent as specified by the board. However, by December 31, 2014, BACB standards of supervision will change such that supervisors of BCBA candidates will be required to pass an online, competency-based training module on BACB experience standards as well as to complete an 8-hour post-certification workshop on supervision. Supervisees must also pass the online training module on the BACB experience standards and register with BACB to begin accruing experience hours. After the aforementioned changes go into effect in 2014, requirements to supervise BCBA candidates and to begin accruing hours will be more in line with other similar behavioral health professions (see Tables 1–5). One final noteworthy difference we found with respect to supervision is that most other behavior health professions, except the LCSW (see National Association of Social Workers, n.d., Supervision for the LCSW), have explicit regulations against supervisors charging a fee for supervision.

Lastly, we found that the board examination, CE requirements, and post-certification requirements of behavior analysts are predominantly commensurate to the board standards for licensure of other behavioral health professionals. Specifically, the BACB requires that every 3 years, candidates accrue a total of 36 hours of CE, 3 of which must be in ethics. By December 2015, an additional 3 hours of CE will be required in supervision for those who supervise registered supervisees and the renewal cycle will change to every 2 years. In regards to the board examination, the BCBA examination is similar to other licensing examinations in that candidates complete multiple-choice questions that cover a breadth of knowledge deemed to be foundational to professional and competent practice in the field. However, as mentioned before, unlike licensure examinations, the BCBA exam does not cover information regarding specific state laws, regulations, or practice because it is a national certification.

Recommendations, Future Considerations, and Conclusions

Recently, questions have arisen concerning certification and licensure for protecting practitioners as well as consumers of behavior analysis (see Green & Johnston, 2009b; Dorsey et al., 2009 for further discussions). We hope the comparisons that we provided set the occasion for evaluation of the proposed model acts by leading professional associations in behavior analysis (i.e., BACB, APBA, and ABAI). In the absence of true competency measures of specific skills sets among the different behavior health professions, legislators, policy makers, insurers, and consumers rely on testimonies, recommendations of close friends or trusted colleagues, and cursory dimensions of the credential. Therefore, it is our hope that we have provided an overview of the apparent requirements of similar behavioral health professions to help behavior analysts hold informed conversations with legislators and stakeholders regarding licensure.

The BACB develops guidelines and sets minimum requirements based on published research outcomes, panel experts of behavior analysts, focus groups composed of diverse groups of behavior analysts, and stakeholders who may be affected by changes in the requirements (e.g., university faculty), or the results of surveying existing credentialed behavior analysts. We recommend further research be conducted to determine the variables that affect consumers' and other stake holders' perceptions of competence. For example, if the public deems a profession more competent based on the total number of supervised experience hours, despite the intensity of that supervision, the BACB may consider increasing the minimum requirements for the supervised experience hours to minimize the challenges credentialed behavior analysts face when dealing with legislatures or insurers. Alternatively, while cursory requirements affect the reputation of the profession, so does the competence of the professionals with the credential. To date, however, we did not find any literature indicating whether additional requirements measurably improve the performance of behavior analysts, ensure competence, or protect consumers. Therefore, we recommend that future research focus on measuring the effectiveness of current board requirements in producing competent behavior analysts. For example, researchers might collect data from state and national boards, universities, and various supervision contexts to examine the type of training received by behavior analysts who had complaints that resulted in disciplinary actions or by candidates who faced difficulties passing the board exam. Another method to collect data on the effectiveness of the board requirements would be to conduct cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys on employers and consumers of services regarding the professional and ethical conduct of credentialed behavior analysts.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that the degree and educational requirements for certification of behavior analysts are commensurate to board standards for licensure of other behavioral health professionals. We found the experience requirements for certification are incommensurate at this time but that the requirements will be more in line with the experience requirements of other professions by the year 2015. ABA, as a profession, is at a critical juncture. To begin establishing itself as a distinct discipline, the BCBA credential needs to achieve greater perceived equity with other behavioral health credentials. The BACB, like all other credentialing boards, has gradually increased the requirements for the credential. To date, 13 states, including Oregon, already have passed (or are in the process of passing) legislation to license behavior analysts and 2 (North Dakota and Ohio) passed state certification (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2013b; Katzen, 2013). The rapid growth of the field presents a vital opportunity for behavior analysts to evaluate the effects of the board standards on the competency of credentialed individuals and provide empirical evidence for such standards.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. The pediatrician's role in the diagnosis and management of autistic spectrum disorder in children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1221–1226. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1221. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) MFT licensing boards. 2011a Retrieved from http://www.aamft.org/imis15/Content/Directories/MFT_Licensing_Boards.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. 2011b Retrieved from http://www.aamft.org/imis15/AAMFT/Home/AAMFT/Default.aspx?hkey=ee4a9da3-cfca-40b4-9a91-40448976ac25. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) Who are marriage and family therapists? 2011c Retrieved from http://www.aamft.org/iMIS15/AAMFT/Press/MFT_Qualifications/Content/About_AAMFT/Qualifications.aspx?hkey=00f76834-705e-4dd9-9dfe-46e6467eb-7ca. [Google Scholar]

- American Board of Professional Psychology. Definition of clinical psychology services. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.abpp.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3307. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J., Burch M. Ethics for behavior analysts (2nd expanded ed.) New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. An upcoming BACB®initiative. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/newsletter/BACB_Newsletter_9-9-11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Certificant registry. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.BACB.com/index.php?page=100155. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. About the BACB. 2013a Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/index.php?page=1. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Behavior analysts licensure/certification statutes. 2013b Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/index.php?page=100170. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. New BCBA degree requirement. 2013c Retrieved from http://www.BACB.com/index.php?page=100378. [Google Scholar]

- California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists. The building of a profession. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.camft.org/Content/Navigation-Menu/EducationalOpportunities/SelfStudy/The-BuildingofaProfession/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health Workforce Studies School of Public Health & NASW Center for Workforce Studies National Association of Social Workers. Licensed social workers in the United States. 2004 Retrieved from http://workforce.socialworkers.org/studies/chapter2_0806.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Social Work Association. Problems with current social work licensure system. 2008 Retrieved from www.clinicalsocialworkassociation.org. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation. Examinations. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.mass.gov/ocabr/licensee/dpl-boards/py/regulations/rules-and-regs/251-cmr-300.html. [Google Scholar]

- Crane D., Shaw A. L., Christenson J. D., Larson J. H., Harper J. M., Feinauer L. L. Comparison of the family therapy educational and experience requirements for licensure or certification in six mental health disciplines. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2010;38:357–373. doi:10.1080/01926187.2010.513895. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M. J., Grier J. E., C., Hunley S. A. The changing face of school psychology: Trends in data and projections for the future. School Psychology Review. 2004;33:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D., DeGue S., Cohen L. M., Morgan R. D. The path to licensure for academic psychologists: How tough is the road? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2006;37:567–586. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.567. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey M. F., Weinberg M., Zane T., Guidi M. M. The case for licensure of applied behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009;2(1):53–58. doi: 10.1007/BF03391738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldevik S., Hastings R. P., Hughes J., Jahr E., Eikeseth S., Cross S. Meta-analysis of early intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:439–450. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851739. doi:10.1080/15374410902851739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan R., Miller J. A. Specialty competencies in school psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Green G. How to evaluate alternative credentials in behavior analysis. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.iabaonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/How-to-Evaluate-Alternative-Credentials-in-Behavior-Analysis-Green-G.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Green G., Johnston J. M. Licensing behavior analysts: Risks and alternatives. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009a;2(1):59–64. doi: 10.1007/BF03391739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green G., Johnston J. M. A primer on professional credentialing: Introduction to invited commentaries on licensing behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009b;2(1):51–52. doi: 10.1007/BF03391737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D., Ziller E., Lambert D., Loux S., Bird D. State licensure laws and the mental health professions: Implications for the rural rental health workforce. Portland, ME: Maine Rural Health Research Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J. M., Shook G. L. Developing behavior analysis at the state level. The Behavior Analyst. 1987;10:199–233. doi: 10.1007/BF03392431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzen B. Patrick signs several bills into law in final days. The Lowell Sun. 2013, 15 January Retrieved from http://www.lowellsun.com/highschoolfootball/ci_22369382/patrick-signs-several-bills-into-law-final-days. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of School Psychologists. States Aligning Credentialing Requirements with the NCSP and NASP Graduate Preparation Standards. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/certification/statencsp.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of School Psychologists. What is a school psychologist? (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/about_sp/whatis.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of School Psychologists. Entry-level training. 2006 Retrieved from http://copsse.education.ufl.edu/docs/IB-4E/1/IB-4E.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. Supervision for the LCSW: Common questions. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.naswct.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=106. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. Practice. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.socialworkers.org/practice/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. Milestones in the development of social work and social welfare. 1995 Retrieved from http://www.socialworkers.org/profession/centennial/milestones_4.htm. [Google Scholar]

- PSYCHPREP. About the CPSE. 2011 Retrieved from http://psychprep.com/Pages/CPSE/WhatisCPSE.htm. [Google Scholar]

- The Riley Guide. Career and education info. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.rileyguide.com/careers/clinical-psychologists.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- Robiner W. N. The mental health professions: Workforce supply and demand, issues, and challenges. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:600–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.05.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook G. L. The professional credential in behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 1993;16(1):87–101. doi: 10.1007/BF03392614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook G. L. An examination of the integrity and future of Behavior Analyst Certification Board credentials. Behavior Modification. 2005;29:562–574. doi: 10.1177/0145445504274203. doi:10.1177/0145445504274203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook G. L., Favell J. E. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board and the profession of behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1(1):44–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03391720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook G. L., Neisworth J. T. Ensuring appropriate qualifications for applied behavior analyst professionals: The Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Exceptionality. 2005;13:3–10. doi: 10.1207/s15327035ex1301_2. [Google Scholar]

- Shook G. L., Van Houten R. Ensuring the competence of behavior analysts. In: Van Houten R., Axelrod S., editors. Behavior analysis and treatment. New York: Plenum; 1993. pp. 171–181. In. (Eds.) pp. [Google Scholar]