Abstract

Introduction

Patient views on quality of care are of paramount importance with respect to the implementation of quality assurance (QA) and improvement (QI) programmes. However, the relevance of patient satisfaction studies is often questioned because of conceptual and methodological problems. Here, it is our belief that a different strategy is necessary.

Objective

To develop a conceptual framework for measuring quality of care seen through the patients' eyes, based on the existing literature on consumer satisfaction in health care and business research.

Results

Patient or consumer satisfaction is regarded as a multidimensional concept, based on a relationship between experiences and expectations. However, where most health care researchers tend to concentrate on the result, patient (dis)satisfaction, a more fruitful approach is to look at the basic components of the concept: expectations (or `needs') and experiences. A conceptual framework – based on the sequence performance, importance, impact – and quality judgements of different categories of patients derived from importance and performance scores of different health care aspects, is elaborated upon and illustrated with empirical evidence.

Conclusions

The new conceptual model, with quality of care indices derived from importance and performance scores, can serve as a framework for QA and QI programmes from the patients' perspective. For selecting quality of care aspects, a category‐specific approach is recommended including the use of focus group discussions.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, quality assurance, quality of care, theory

Introduction

Patient satisfaction plays an important role in maintaining relationships between patients and health care providers, 1 compliance with medical regimens, 2 and continued use of medical services. 3 Also, patient satisfaction is felt to be of paramount importance with respect to quality assurance (QA) and the expected outcome of care. 4 , 5, 6, –7 However, the relevance of patient satisfaction studies with respect to quality management and improvement in the health care sector is often questioned because of conceptual and operational problems, such as reliability and validity of patient reports, determinants associated with patient satisfaction, and the ambiguity of the patient satisfaction concept. 8 , 9, 10, 11, –12 Despite the work of Linder‐Pelz, 13 , 14 Pascoe 15 and, more recently, Strasser et al., 11 a theoretical framework is often missing. 16 Theory and methodology in this field appear to have developed along separate lines of interest.

In market research a somewhat different approach was developed by Parasuraman et al. 17 , 18 Rather than focusing on (dis)satisfaction, their service quality (SERVQUAL) model concentrates on expectations and experiences. Both elements are considered as important parts of a process towards continuous quality improvement (CQI), and are measured in a way directly related to the theory behind the SERVQUAL model. Although the value of looking at expectations 9 , 19 and the appropriateness of the SERVQUAL model 20 can be questioned, we think that the methodology applied in business research could fill the gap between theory and practice within the field of patient satisfaction research.

This article briefly reviews some of the relevant theories that have been applied to the concept of patient (or consumer) satisfaction and quality of care, both in health care and marketing sectors. Next, a conceptual framework for measuring quality of care from the patients' perspective will be presented and further elaborated upon by discussing its separate elements and relevant background variables related to patient's judgements of quality of care. Finally, the relevance of the new conceptual framework is illustrated by an example from a study on the quality of care delivered by Dutch general practitioners (GPs).

Patient satisfaction and its theoretical implications

Quality of care from the patient's perspective can be defined as `the totality of features and characteristics of a health care product or services, that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs of the consumers of these products or services'. 21 With patient satisfaction being considered as one of the possible operationalizations of the quality of care concept, 22 elements from this definition are apparent in most publications that focus on patient satisfaction. 23 , 24 Some describe the concept as a personal evaluation (or rating) of health care services and providers based on personal preferences and expectations. 25 , 26 Others 27 refer to patient satisfaction as a function between orientations of patients and conditions provided by health care professionals, and in their view patients differ in what they want and expect from their encounters with health care professionals or health care institutions. The notion of a balanced evaluation between experiences and expectations can also be found in Lebow, 28 who defines patient satisfaction as the extent to which services gratify the desires of patients regarding structure, process and outcome dimensions and characteristics.

Multidimensionality is also a central element in the work of both Linder‐Pelz 13 , 14 and Pascoe. 15 Linder‐Pelz considered patient satisfaction as an individual's positive attitude toward – or a positive evaluation of – health care services experienced. In this view, individuals evaluate distinct aspects of their care when making an overall evaluation of (parts of) the health care system. The overall attitude of an individual person, then, is a weighted sum of expectancies and their affective value judgements. However, this expectancy‐value model, which builds on Fishbein and Ajzen, 29 has been criticized for operational and conceptual weaknesses, like, for example, the vagueness of the expectation and value components. 30 Pascoe 15 described patient (dis)satisfaction as the result of a comparison of salient characteristics of the individual's health care experience with a subjective standard. This comparative process includes two inter‐related psychological activities: (1) a cognitive evaluation, or grading, and (2) an affective response, or emotional reaction, to the structure, process and outcome of health care services. The subjective standard for judging a health care experience may be the ideal situation, a subjective sense of what one deserves, an average translation of past experiences in similar situations, a minimally acceptable level, or a combination of these elements.

More recently, Strasser and Davies 31 considered patient satisfaction as a direct response to situations experienced. Subsequently, patient satisfaction was defined as the patient's value judgement and subsequent reactions to the stimuli perceived just before, during and after contact with health care services. This model has been elaborated further by Strasser et al., 11 who described patient satisfaction as (1) a cognitive and an affective perceptual process towards the formation of attitudes, (2) a multidimensional construct and a single global construct, (3) a dynamic process along a variety of dimensions such as time, self‐perceived equity, and pain, (4) a form of attitudinal reaction, expressed as either cognitive or affective or both but not behavioural, (5) an iterative process of attitude formation and subsequent behavioural reactions, and (6) an individual process depending on the patient's particular values, beliefs, expectations, previous health care experiences, and sociodemographic factors including his/her current health care status.

In theory, the majority of health care researchers relate patient satisfaction to the `experiences' and `needs' of individuals with respect to health care services, with needs being operationalized as `expectations', what is `important', `desirable' or `what should be'. 32 , 33, –34 However, most empirical studies focus on the result, patient (dis)satisfaction, instead of the two basic components: needs and experiences. Owing to the difficult relationship between experiences and patient satisfaction scores, little progress has been made in what should be one of the main functions of `quality of care' research: QA and QI according to the ideas of the users of health care services.

Also, in market research, consumer satisfaction is often seen as a function of performance expectations and the degree to which performances depart from expectations. 35 Following a model proposed by Oliver, 36 , 37 underlying assumptions are rather straightforward: (1) if a product matches the expectations then quality is satisfactory; (2) when a product fails to match the expectations then quality will be judged as unsatisfactory; and (3) if a product exceeds the expectations, quality will be judged as very satisfactory or even excellent. Dissatisfaction results from unmet expectations: as fulfilment exceeds expectations, satisfaction increases. 38 , 39, 40, 41, –42 According to Parasuraman et al. 17 , 18 size and direction of the gap between expected and perceived services depends on (1) consumer expectations and management perceptions of these expectations, (2) management perceptions of expectations and the service quality specifications, (3) service quality specifications and actual service delivery, and (4) actual service delivery and external communications about the service.

Towards a new conceptual framework for quality of care research

According to the SERVQUAL model, applied to the health care sector by Babakus and Mangold, 43 quality judgements (Q) of individuals (i) would be equal to the Perception (P) minus the Expectation (E) regarding different health care aspects (j), or, in formula: [Link]

However, with regard to expectations Fitzpatrick and Hopkins 19 found that (1) unmet expectations expressed before the actual visit did not become the focus of critical comments afterwards, (2) comments expressed after consultation concerned aspects not mentioned before the consultation and (3) expectations were often expressed in a tentative way. Differences between expectations and perceived performance are therefore described as `artificial and misleading, based on methods that do not capture the way patients really anticipate and respond to medical encounters'. The existence of expectations is also questioned by Williams, 9 who argues that patients sometimes take health care services for granted, which might be seen as either a non‐existence of expectations and/or as a reflection of a passive role adopted by patients. Furthermore, expectations tend to shift over time because of previous experiences, 40 memory effects or cognitive dissonance. 31 Given the ambiguity of the `expectations' component, we believe that research on quality of care from the patients' perspective should focus on concepts other than patients' expectations, or at least should use a clear definition of the concept. `Expectations' based on previous experiences differ from `expectations' clarifying the `needs' or `desires' of users of health care services.

We believe a more fruitful approach is suggested by Zastowny et al., 44 who concentrate on three quality of care dimensions: performance, importance and impact. In their Patient Experience Survey (PES) performance is measured by problem frequency. Good performance is associated with good quality of care with respect to certain aspects or combination of aspects, whereas relatively poor performance is associated with poor quality of care. Although problem or poor performance frequency are highly relevant in QA programmes, some problems are more important to patients than others. Therefore, an importance component is added to the model as a weight factor. Problem incidence and importance scores are combined into quality impact indices for each aspect of care included in the measure ranging from 0 to 100.

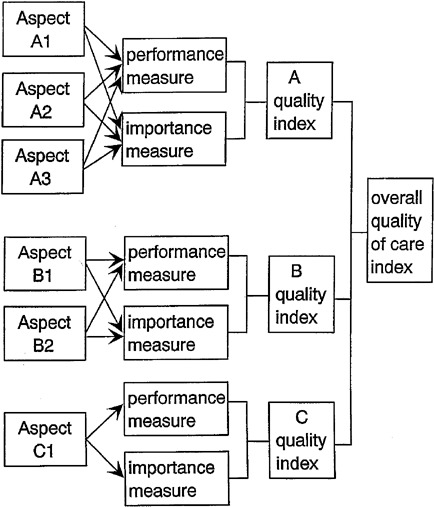

As a conceptual framework, the PES model can also be used in settings other than the hospital sector it was designed for, like, for example, the home care sector. In the original PES model, importance is defined as the degree to which performance is empirically related to satisfaction and calculated by applying independent regression analyses for each aspect of care on overall satisfaction scores. However, we think that QA and QI programmes would benefit more from cognitive quality of care scores based on actual experiences of the users of health care services rather than from subjective patient satisfaction judgements, which are only in small part, related to the actual performances of health care services. Our suggestion is, therefore, to alter the PES model by leaving out patient satisfaction and adding a component focusing on the importance of the quality of care aspects. Whether the different quality judgements result in (dis)satisfaction is undecided. This is not because satisfaction scores are irrelevant with respect to the QA and QI processes, but because they are only partially related to the actual experiences and needs and, therefore, are less suitable for calculating quality of care scores. This adjusted version of the PES framework is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of a series of new measuring instruments for quality of care from the patient's perspective.

Importance and performance can be measured directly by using multipoint Likert scales. The quality judgement (Q) of an individual (i) is equal to the performance score (P) multiplied by the importance score (I) of different health care aspects (j). As a formula this equates to: [Link]

To elaborate this conceptual framework further, we subsequently discuss the (P)erformance and the (I)mportance component of the formula, and the variables associated with individual differences.

The performance component

Patients distinguish between different aspects of health care delivery. With reference to this multidimensionality, Hall and Dornan 45 , 46 presented a meta‐analysis of 221 studies investigating patient satisfaction with medical care. Apart from `patient satisfaction' itself, which can be considered as an `umbrella' concept, they identified a core of 11 different aspects. The three aspects most frequently desired are, in declining order: humaneness (65% of all studies), informativeness (50%), and overall quality of care (45%). Other aspects include the technical competence or technical skills of the health care provider (43%), bureaucratic procedures (28%), access to and availability of health care services (27%), costs of treatment and flexibility of payment mechanisms (18%), the comfort of seating, attractiveness of waiting rooms, clarity of signs and directions, quietness and neatness of health care facilities (16%), continuity of care (6%), outcome of the health care process, in terms of usefulness or effectiveness (4%), and attention to psycho‐social problems (3%). More recently, a meta‐analysis was carried out which included a sample of 40 studies focusing on patients' judgements of care provided by their general practitioner (GP). 47 Apart from differences in percentages, the aspects covered by these 40 studies paralleled those found by Hall and Dornan. Empirical evidence for the multidimensionality of the quality of care concept can be found in a series of studies that used different types of factor analysis as analysing techniques. Most of these studies 8 , 25 , 48 , 49 concluded that responses are multidimensional, although others have suggested a unidimensional structure. 50

An indication for the accuracy of perceptions can be derived from the relationship between performance and/or patient satisfaction scores and more objective measures of service delivery and perceived differences between care providers. Based on a meta‐analysis of 41 observation studies carried out by Hall et al. 51 it was found that patient satisfaction was related to (a) objective measures of information giving, technical and interpersonal competence, (b) providers' partnership building, and (c) socio‐emotional behaviour, such as a provider's non‐verbal behaviour, social conversation and positive talk. Other studies claimed a negative relationship between patient satisfaction and physician experience, 45 status characteristics of physicians 52 and the number of health care providers in a particular setting. 53 More generally, the perception of health care services and health care related subjects can be divided into the three broad components: the structure of the health care system, the health care process itself, and the outcome of this health care process. 54

If one is interested in quality of care from the perspective of specific groups of users of health care services, e.g. patients suffering from specific chronic diseases, two things have to be kept in mind. Firstly, most instruments measuring patient satisfaction or quality of care are based on the perspective of researchers, providers of health care services or policy makers, with patients only being involved in the study as respondents. The fact that the perspectives of health care providers and the users of health care services differ substantially, 55 , 56, 57, 58, 59, –60 casts doubt on the validity of such instruments for measuring quality of care through the patients' eyes. Secondly, most existing instruments focus on generic quality of care and not on disease‐related factors that refer to specific categories of patients. Although suitable in general population studies, such generic aspects deny the specific needs and experiences of large sub‐groups within the general population. One of the most important aspects of quality of care judged by a group of patients with chronic non‐specific lung diseases (CNSLD) was `a dust‐ and smoke‐free practice location', 61 and similarly rheumatic patients mention aspects such as the furniture in the practice location. 62 Both aspects can be considered as disease‐specific, where `the wish to be taken seriously' can be regarded as generic.

The importance component

Different techniques can be applied to measure the importance component such as ranking or the application of Likert scales. Ranking the different aspects in terms of their relative importance is probably the most informative procedure but also the most time consuming one, especially when the number of aspects exceeds 20. Application of `Likert‐type' items is probably the easiest way to measure patients' opinions on the importance of aspects and can be applied in postal surveys. Here attention must be paid to the fact that ordinary Likert scales applied in this field tend to be highly skewed towards the `important' dimension. A workable solution is to have greater differentiation on the positive side of the continuum. In a pilot study, which was part of the development of a series of quality of care measuring instruments, 63 we applied Likert scale items with 4‐point response choices: `not important' (score 0), `fairly important' (score 3), `important' (score 6), `extremely important' (score 10). Scale scores were calculated by transforming t‐values on the basis of the empirical distribution of the respondents into Z‐scores and standardizing these Z‐scores on values between 0 and 10. 64 This solution proved to be workable.

The individual characteristics

Individual differences related to patient satisfaction and quality of care scores can be split into three broad categories: (1) socio‐demographic characteristics, (2) the patient's medical profile, including his/her current health status, and (3) attitudes and behavioural intentions.

Socio‐demographic characteristics

Positive, negative and no relationships were found with respect to age, income, socio‐economic class, marital status, race and family size. 15 , 27 , 65 If relationships are found, their effect sizes (or the unique percentages of variance accounted for) are generally small. Hall and Dornan 66 summarized the literature on the relation between patient satisfaction and socio‐demographic characteristics in a meta‐analysis of 110 studies. Results indicated that greater satisfaction was significantly associated with higher age (rmean = 0.13) and with less education (rmean = –0.03), although magnitudes of the correlations were small.

Characteristics related to the patient's health status

Reviewing the literature on the relationship between patient satisfaction and health status, Weiss 65 reports on four studies that failed to find such a relationship, while three studies found that persons in poorer health were less satisfied with the medical care received. This last finding supports earlier conclusions that among the chronically ill there was a tendency towards evaluating health care services rather negatively. 30 With respect to the relationship between the utilization of health care services and quality of care measures, Ware et al. 67 noted that 26 out of 30 statistical tests indicated that greater use of health services is associated with greater satisfaction. Less support for the hypothesis that more frequent visits to health care services are related to higher patient satisfaction scores is reported by Pascoe. 15 In his review, eight out of 41 studies showed a significant positive relationship, three revealed a negative relationship and the majority did not find any relationship at all. In a two‐level analysis Sixma et al. 68 show that health related indicators have an independent significant effect on patient satisfaction. With morbidity measures included, the frequency with which the GP was consulted over a 12‐month period did not show an independent effect on the patient's satisfaction scores.

Attitudes and behavioural intentions

Patient satisfaction and quality of care scores may also be influenced by factors such as the attitude of the patient towards medical services and/or health care providers and the length of time patients are enlisted with particular health care services. Weiss 65 reported that patient satisfaction ratings were influenced positively by confidence in the local medical care system (r = 0.34, effect size = 0.05), while no significant relationships were found between patient satisfaction and health locus of control measures. Continuity of care, with patients being treated on a regular basis by the same health care provider, is also associated with higher satisfaction scores, but again the effect sizes are generally small. 15 , 50 , 66 This positive relationship can be explained by familiarization, although an alternative explanation could be that correlations are high because disatisfied patients have dropped out. Finally, in a longitudinal study it was hypothesized that the best predictors of patient satisfaction at a given point in time would be prior satisfaction. Since modifications of norms and perceptions and new experiences would result in altered attitudes, the expected relationship should be a moderately strong one. This assumption was confirmed by empirical results, in which a significant correlation (r = 0.39) was found between initial satisfaction with the physician and the satisfaction measured in a second report 12 months later. 69

The patients' perspective

With regard to the performance component two aspects need some further discussion: (1) the patients' perspective, and (2) the inclusion of disease specific indicators. If frequent users of health care services, such as disabled or frail elderly people are considered as experts by virtue of their greater experience in evaluating the quality of health care services, their views should lead the development process. Here qualitative methods, such as focus group discussions or in‐depth interviews can play an important part.

Focus group discussions or focus group panels are mostly used for exploring a specific set of issues, such as the experiences of risk‐taking gay men with respect to AIDS prevention activities, 70 the development of consensus guidelines in general practice, 71 the efficiency of maternal health services, 72 and the relative values of physician work. 73 Focus group or focus panel discussions (focus groups generally consist of participants who do not know each other and meet on a one time basis, whereas panels generally refer to a series of sessions) can be distinguished from the broader category of group interviews by the explicit use of group interaction as research data. 74 , 75 The group is `focused' around a collective activity, varying from watching and discussing a movie to talking about a particular set of questions or one specific topic. 76 Such a topic could include patients' views on quality of care. With respect to patient satisfaction, focus groups involving patients have successfully been used in studies on, e.g. hospital programmes to improve in‐patient care on paediatrics 77 , 78 and the development of an instrument for measuring quality of life. 79

Focus group discussions with experienced patients, if possible in combination with a computer‐assisted concept mapping session, can result in a broad range of possible quality of care indicators from the patients' point of view. Such quality of care indicators include generic aspects as well as those relevant to the specific category of patients involved in the focus group. Examples of generic aspects are the wish to be taken seriously or short waiting times. Category specific aspects mentioned by a group of CNSLD patients include aspects such as smoke‐ and dust‐free buildings and emergency arrangements with health care services in case of asthma attacks. Operationalized, these aspects represent the `needs' or `demands' of patients with regards to the functioning of the health care system in an ideal situation. When performances of health care services and providers meet these needs, good quality of care from the patients' perspective is undisputed; if not, quality of care is perceived as far from optimal.

Assessing the new conceptual framework

Based on the conceptual framework described in this article a series of four new measuring instruments was developed, tailored to the needs of: (1) CNSLD patients, (2) rheumatic patients, (3) disabled people, and (4) frail elderly people. Two of these instruments – the QUOTE‐CNSLD and QUOTE‐rheumatism, with the acronym QUOTE standing for QUality Of care Through the patients' Eyes – were used in a Community Intervention Trial (CIT) to improve quality of care from the patients perspective. Here, we will limit ourselves to an evaluation of health care services, analysing data from a sub‐sample of 287 patients with rheumatic diseases being 55 years of age or older. According to self‐reports 44% of these patients had rheumatoid arthritis, 41% had peripheral osteoarthritis, 7% had osteoporosis and 8% reported other rheumatic disease. In the last year 94% of the respondents had made use of the services of GPs, 56% visited a rheumatologist, 56% visited a physiotherapist, and 30% made use of home‐help services.

Quality of care aspects included in the QUOTE‐rheumatism were derived from a series of focus group discussions with three groups of rheumatic patients, in combination with the results of a series of empirical tests in the development phase of this measuring instrument. Included in the questionnaire were 40 quality of care aspects: 16 generic aspects, 16 disease‐specific aspects and eight aspects suggested by patients living in the two regions involved in the study. The 32 generic and disease‐specific indicators are part of the original QUOTE‐rheumatism instrument. In the original version generic aspects grouped together in a `process' (eight items, Cronbach's alpha:.74) and a `structure' dimension (eight items, Cronbach's alpha: 0.81). The 16 disease‐specific aspects grouped together in one `category‐specific' dimension (Cronbach's alpha: 0.88). This factorial structure and reliability coefficients were mirrored in the CIT for the entire response group of 518 rheumatic patients as well as for our subsample of 287 patients. The 40 quality of care aspects reflect the `expectations' (or better, the `needs' or `desires') component of our conceptual framework.

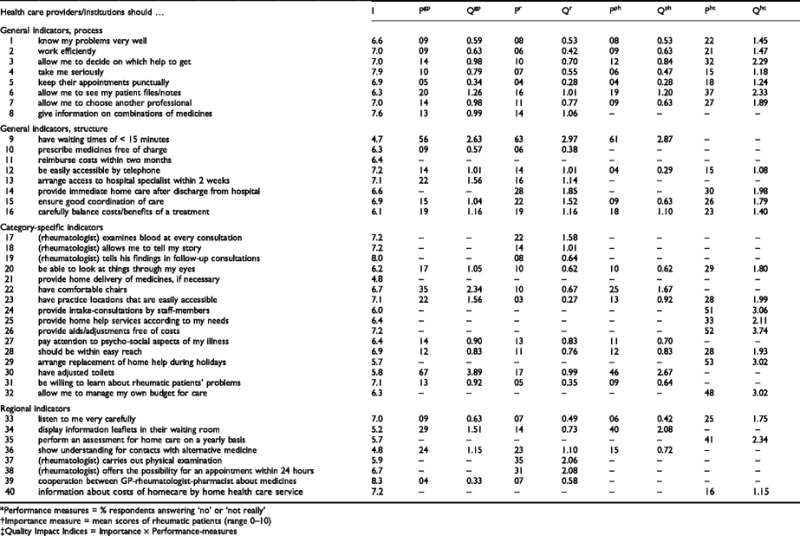

In the questionnaire, quality of care aspects were formulated as importance and performance statements. Importance was assessed without specifying professions or type of organization. Performance judgements referred to contact with GPs (and general practice), rheumatologists (or hospital care), physiotherapists, and home help services. Importance and performance were measured by 4‐point response categories (see Appendix A). Importance scores were derived from the empirical distribution, with scores being converted into Z‐scores and subsequently standardized between 0 and 10. Performance scores were calculated by combining percentages `no' and `not really'. Importance and performance scores correlated weakly (rmean = 0.12), with highest correlations not reaching the 0.50 level. Table 1 illustrates the relationship between the importance judgements (I), performance scores (P) and quality impact indices (Q), regarding the 40 quality of care aspects.

Table 1.

Importance (I)* Performance (P)† and Quality Impact Indices (Q)‡ regarding the services of general practitioners (gp), rheumatologists (r), physiotherapists (ph) and home health care services (hc), derived from a convenience sample of 287 non‐institutionalized rheumatic patients of >55 yearss of age

With respect to the quality of care aspects reported in Table 1, one can argue that part of the items are virtually indistinguishable from those used in many other `satisfaction with care' studies, such as the studies reported by Hall and Dornan, 66 , 80 Rubin, 8 Ware 81 and Wensing. 47 However, this is only true for part of the items. Looking at their content and at the way they were formulated, most items are more informative and more practical than items in existing patient satisfaction scales, and better reflect the needs of specific categories of patients. Not every item is relevant to each discipline. This resulted in 25 indicators for GPs, 31 indicators for the rheumatologist, 21 indicators for physiotherapists, and 22 indicators for home health care services.

Table 1 offers different types of information relevant to quality assurance policies. Firstly, the relative importance of quality indicators is shown in the first row (I‐scores). High ranking indicators were item 39 (`good cooperation between GPs, rheumatologists and pharmacies when medicines are prescribed'), item 19 (`patients being informed by the rheumatologist about his/her findings at the end of each consultation') and item 4 (`the wish of patients to be taken seriously'). Importance scores range from 4.7 to 8.3 on a scale from 0 (`unimportant') to 10 (`extremely important'). Secondly, the performance of health care providers and institutions can be deduced from the P‐columns in Table 1. For instance the performance of GPs was poor as regards indicator no. 30 (`the availability of an adjusted toilet'). The P‐score of 67 indicates that 67% of the respondents reported that their GP did not have an adjusted toilet. Thirdly, the relative impact of priorities and performances on quality can be deduced from the Q‐columns. The importance of item 6 (`patients are allowed to see their case notes/files, if they want to') is valued at 6.3, and 37% of the respondents reported that the home care agency did not supply this service. The quality impact (Q = 2.33) is rather high, as a result of the product of a relatively high (non‐)performance score (P = 0.37) and a medium importance score (Q = 6.3).

Quality impact indices can be used to compare within and between professions and institutions, both on individual aspects and combinations of aspects. Applied in this way, one could argue that a successful policy towards QI within the home care sector should focus on aspects like the costs of home care services (item 26), the assessment procedure when patients apply for home help (item 24), availability of home help during the holiday season (item 29) and possibilities for patients to manage their own care budget (item 32). These four aspects show impact indices above 3.0. Other aspects, such as whether or not the patient is taken seriously, are judged as extremely important, but here the `needs' of patients are almost completely met by the performances of, for instance, GPs or rheumatologists. There is hardly any room for further improvement.

Conclusions and discussion

This article began with a review of some of the relevant theories applied in research on patient satisfaction and quality of care. Based on the work carried out by Zastowny et al., 44 a new conceptual framework for measuring quality of care from the patient's perspective was presented, based on the sequence: performance, importance and impact. This model was further elaborated, by discussing its separate elements and relevant background variables related to patient's judgements on aspects of quality of care and the way in which these can be specified using qualitative methods such as focus group discussions. Finally, the relevance of the new conceptual framework was illustrated by assessing the quality of GP care received by patients with chronic non‐specific lung diseases.

We believe that instruments for measuring quality of care based on the conceptual model presented can play an important function in quality assurance and improvement processes. With respect to the `performance' component it was established that patient's judgements are related to different aspects of the health care system, and therefore measuring instruments should reflect the multidimensionality of the care giving process. Also, we agree with Cleary and Edgman‐Levital, 82 that questions asking for `reports' tend to reflect better the quality of care and are more interpretable and actionable for quality improvement purposes than ratings of satisfaction or excellence. Regarding the `importance' component, attention has to be paid to the way this component is measured. Likert‐type items, with answering categories skewed toward the `important' end, provide an acceptable solution. Looking at patient characteristics, which are significantly related to patient satisfaction, many show only modest effect sizes and findings have not been consistent across studies. If patient characteristics are included in the research (e.g. as background variables to test the stability of quality of care parameters among subgroups or to calculate category‐adjusted importance rates) respondent's age, education and morbidity status are logical choices.

The conceptual framework developed by Zastowny et al. proved to be fruitful in an empirical study. Expectations (or `needs') of patients were derived from, and further specified in a series of focus panel discussions at the start of the project. This approach illustrates that patients should be involved in the development of quality of care measuring instruments from the very beginning. The instrument presented in this study differs from other frequently used patient satisfaction or quality of care scales, such as the ones used by Rubin et al., 83 McCusker, 84 Brody et al., 85 and Cryns et al. 86 Patients' judgements on the importance of quality of care aspects specify the relevance of selected aspects for individuals or groups of patients, and can function as a weighting factor in evaluating performance as part of quality improvement programmes.

Although the instruments derived from the conceptual framework presented in this article were developed for the situation in the Netherlands, the framework itself can be applied in other countries. However, since health care systems differ from country to country, and within countries sometimes from district to district, a process of cross‐cultural validation involving additional focus group discussions with experts and patients can play an important role. In this way, instruments based on the conceptual framework can be regarded as a method, more than a set of items. Also, the scope of the instruments is not limited to health care providers but also includes functions of care as perceived by (non‐institutionalized) patients. Providers who execute these functions can differ from country to country, and from region to region.

Acknowledgements

The research project `Quality of Home Care from the Patients' Perspective: The Development and Assessment of a New Measuring Instrument′, on which this manuscript is based, is supported by research funds from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO 900–571–054 and NWO 900–571–097). The research forms part of a wider project entitled SCOPE, Supporting Clinical Outcomes in Primary Care for the Elderly. The SCOPE project is funded by the European Commission under the Biomedicine and Health Programme.

References

- 1. Marquis MS, Ross Davies A, Ware JE. Patient satisfaction and change in medical care provider: a longitudinal study. Medical Care, 1983; 21 : 821 829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wartman SA, Morlock LL, Malitz FE, Palm EA. Patient understanding and satisfaction as predictors of compliance. Medical Care, 1983; 21 : 886 891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas JW. Relating satisfaction with access to utilization of services. Medical Care, 1984; 22 : 553 568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donabedian A. Quality assessment and assurance: unity of purpose, diversity of means. Inquiry, 1988; 25 : 173 192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Donabedian A. The Quality of care: how can it be assessed? Journal of the American Medical Association, 1988; 260 : 1743 1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donabedian A. Quality assurance in health care: consumers' role. Quality in Health Care, 1992; 1 : 247 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aharony L & Strasser S. Patient satisfaction: what we know about and what we still need to explore. Medical Care Review, 1993; 50 : 49 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubin HR, Ware JE, Hays RD. The PJHQ Questionnaire; exploratory factor analysis and empirical scale construction. Medical Care, 1990; (9) Supplement: S22–S29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Social Science and Medicine, 1994; 38 : 509 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ross CA, Steward CA, Sinacone JM. A Comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Medical Care, 1995; 33 : 392 406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strasser S, Aharony L, Greenberger D. The Patient satisfaction process: moving toward a comprehensive model. Medical Care Review, 1993; 50 : 219 248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ovretveit J. Health Service Quality: an Introduction to Quality Methods for Health Services. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd, 1992.

- 13. Linder‐Pelz S. Toward a theory of patient satisfaction. Social Science and Medicine, 1982; 16 : 577 582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Linder‐Pelz S. Social psychological determinants of patient satisfaction: a test of five hypothesis. Social Science and Medicine, 1982; 16 : 583 589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pascoe GC. Patient satisfaction in primary health care: a literature review and analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1983; 6 : 185 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Campen C, Sixma H, Friele RD, Kerssens JJ, Peters L. Quality of care and patient satisfaction: a review of measuring instruments. Medical Care Research and Review, 1995; 52 : 109 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 1985; 49 : 41 50. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LLSERVQUAL. A multiple‐item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 1988; 64 : 12 40. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fitzpatrick R & Hopkins A. Problems in the conceptual frame work of patient satisfaction research: an empirical exploration. Sociology of Health and Illness, 1983; 5 : 297 311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thompson AGH & Suñol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal For Quality In Health Care, 1995; 7 : 127 141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nederlands Normalisatie Instituut (NNI) . Kwaliteitszorg en elementen van een kwaliteitssysteem, deel 2: richtlijnen voor diensten. Nederlandse Norm. NEN‐ISO 9004.2. Delft: Nederlands Normalisatie Instituut, 1992.

- 22. Harteloh PPM, Sprij B, Casparie AF. Patëintsatisfactie en kwaliteit: een problematische relatie. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 1992; 47 : 157 165. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nationale Raad voor de Volksgezondheid (NRV) . Bruikbaarheid van ISO‐normen voor de ontwikkeling van kwaliteitssystemen. Zoetermeer: NRV, 1991.

- 24. Casparie AF. Kwaliteitssystemen in de gezondheidszorg: kanttekeningen bij de ISO‐normen. Medisch Contact, 1992; 47 : 238 241. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ware JE, Snyder MK, Wright WR, Davies AR. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1983; 6 : 236 247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ware JE & Hays RD. Methods for measuring patient satisfaction with specific medical encounters. Medical Care, 1988; 26 : 393 402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fox JG & Storms DM. A different approach to sociodemographic predictors of satisfaction with health care. Social Science and Medicine, 1981; 15 A: 557 564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lebow JL. Research assessing consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment: a review of findings. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1983; 6 : 211 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fishbein M & Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: an Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: MA. Addison‐Wesley, 1975.

- 30. Carr‐Hill RA. The measurement of patient satisfaction. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 1992; 14 : 236 249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Strasser S & Davis RM. Measuring Patient Satisfaction for Improved Patient Services. Ann Arbor, MI. Health Administration Press, 1990.

- 32. Pope C. Consumer satisfaction in a health maintenance organisation. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1978; 3 : 406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Green JY, Weinberger M, Mamlin JJ. Patient attitudes towards health care: expectations of primary care in a clinic setting. Social Science and Medicine, 1980; 14 A: 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zastowny TR, Roghmann KL, Hengst A. Satisfaction with medical care: replications and theoretic reevaluation. Medical Care, 1983; 21 : 294 322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bettman JR.. Consumer psychology. Annual Review On Psychology, 1986; 2 : 275 289. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oliver RL. A theoretical reinterpretation of expectation and disconfirmation effects on posterior product evaluation. Experiences in the field. In: Day RL, Hunt K (Eds ) Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977.

- 37. Oliver RL. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 1980; 17 : 460 486. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Swan JE & Combs LJ. Product performance and consumer satisfaction: a new concept. Journal of Marketing, 1976; 40 : 25 33. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Swan JE. Consumer satisfaction with a retail store related to the fulfilment of expectations on an initial shopping trip. In: Day RL, Hunt K (Eds) Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977.

- 40. LaTour SA & Peat N. The role of situationally produced expectations, other's experiences and prior experience in determining consumer satisfaction. In: Olson JE (ed) Advances in Consumer Research VI. Ann Arbor MI. Association for Consumer Research, 1980.

- 41. Swan JE & Trawick F. Disconfirmation of expectations and satisfaction with a retail service. Journal of Retailing, 1981; 57 : 49 67. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Swan JE, Sawyer JC, Van Matre JG, McGee GW. Deepening the understanding of hospital patient satisfaction: fulfilment and equity effects. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 1985; 5 : 7 18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Babakus E & Mangold WG. Adapting the SERVQUAL scale to hospital services: an empirical investigation. Health Services Research, 1992; 26 : 767 786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zastowny TR, Stratmann WC, Adams EH, Fox ML. Patient satisfaction and experience with health services and quality of care. Quality Management in Health Care, 1995; 3 : 50 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hall JA & Dornan MC. Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care: a meta‐analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 1990; 30 : 811 818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hall JA & Dornan MC. What patients like about their medical care and how often they are asked: a meta‐analysis of the satisfaction literature. Social Science and Medicine, 1988; 27 : 935 939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wensing M, Grol R, Smits A. Quality judgements by patients on general practice care: a literature analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 1994; 38 : 45 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stamps PL & Berger Finkelstein J. Statistical analysis of an attitude scale to measure patient satisfaction with medical care. Medical Care, 1981; 19 : 1108 1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Linder‐Pelz S & Struening EL. The multidimensionality of patient satisfaction with a clinic visit. Journal of Community Health, 1985; 10 : 42 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. DiMatteo MR & Hays R. The significance of patients perceptions of physician conduct; a study of patient satisfaction in a family practice centre. Journal of Community Health, 1980; 6 : 18 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta‐analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Medical Care, 1988; 26 : 657 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Duff RS. Physician status characteristics and clients satisfaction in two types of medical practice. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1982; 23 : 317 329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Steven ID & Douglas RM. Dissatisfaction in general practice: what do patients really want? The Medical Journal of Australia, 1988; 149 : 280 282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 1966; 166–206. [PubMed]

- 55. Potts MK, Mazucca SA, Brandt KD. Views of patients and physicians regarding the importance of various aspects of arthritis treatment: correlations with health status and patient satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling, 1986; 8 : 125 134. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smith CH & Armstrong D. Comparison of criteria derived by government and patients for evaluating general practitioner services. British Medical Journal, 1989; 299 : 494 496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Batalden PB & Nelson EC. Hospital quality: patient, physician and employee judgments. International Journal of Quality Assurance, 1991; 3 : 7 17. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bensing JM. Wie zegt dat dit een goed consult is? Huisarts en Wetenschap, 1991; 34 : 21 29. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bensing JM & Dronkers D. Instrumental and affective aspects of physician behavior. Medical Care, 1992; 30 : 283 298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Waal MAE, Lako CJ, Casparie AF. Voorkeuren voor aspecten van zorg met betrekking tot de kwaliteit: een onderzoek bij specialisten en bij patiënten met een chronische aandoening. Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit, 1993.

- 61. Van Campen C, Sixma H, Kerssens JJ, Peters L. Assessing Non‐institutionalized asthma and COPD patients' priorities and perceptions of quality of health care; the development of the QUOTE‐CNSLD instrument. Journal of Asthma, 1997; 34(6): 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62. Van Campen C, Sixma H, Kerssens JJ, Peters L, Rasker JJ. Assessing patients' priorities and perceptions of the quality of health care; the development of the QUOTE‐rheumatic‐patients instrument. British Journal of Rheumatology, 1998; 37: 362–368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63. Sixma H & Van Campen C,. Kwaliteit van zorg vanuit het perspectief van gebruikers. Kwaliteit in Beeld, 1996; 2 : 12 14. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Swanborn PG. Schaaltechnieken; theorie en praktijk van acht eenvoudige procedures. Amsterdam: Boom Meppel, 1982.

- 65. Weiss GL. Patient satisfaction with primary medical care: evaluation of sociodemographic and predispositional factors. Medical Care, 1988; 26 : 383 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hall JA & Dornan MC. Meta‐analysis of satisfaction with medical care: description of research domain and analysis of overall satisfaction levels. Social Science and Medicine, 1988; 27 : 637 644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ware JE, Davies‐Avery A, Stewart AL. The measurement and meaning of patient satisfaction. Health and Medical Care Services Review, 1978; 1 : 1 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sixma H, Spreeuwenberg P, Van Der Pasch M, Patient satisfaction with the general practitioner: a two‐level analysis. Medical Care, 1998; 2 : 212 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gray LC. Consumer satisfaction with physician provided services: a panel study. Social Science and Medicine, 1980; 14 : 65 73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hospers HJ, Molenaar S, Kok G. Focus group interviews with risk‐taking gay men: appraisal of AIDS prevention activities, explanations for sexual risk‐taking, and needs for support. Patient Education and Counseling, 1994; 24 : 299 306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fardy HJ & Jeffs D. Focus‐groups: a method for developing consensus guidelines in general practice. Family Practice, 1994; 11 : 325 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jaffre Y & Prual A. Midwives in Niger: an uncomfortable position between social behaviours and health care constraints. Social Science and Medicine, 1994; 38 : 1069 1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kahan JP, Morton SC, Farris HH, Kominski GF, Donovan AJ. Panel processes for revising relative values of physician work. A pilot study. Medical Care, 1994; 32 : 1069 1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Morgan D. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. London: Sage, 1988.

- 75. Kitzinger J. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 1995; 311 : 299 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kitzinger J. The methodology of Focus Groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health and Illness, 1994; 16 : 103 121. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Smith JA, Scammon DL, Beck SL. Using patient focus groups for new patient services. Joint Community Journal On Quality Improvement, 1995; 21 : 22 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Budreau G & Chase L. A family‐centered approach to the development of a pediatric family satisfaction questionnaire. Pediatric Nursing, 1994; 120 : 604 608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. World Health Organization . Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOOQOL). Copenhagen: WHO, 1993. [PubMed]

- 80. Hall JA & Dornan MC. What patients like about their medical care and how often they are asked: a meta‐analysis of the satisfaction literature. Social Science and Medicine, 1988; 27 (9): 935 939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ware JE, Davies‐Avery A, Stewart AL. The measurement and meaning of patient satisfaction. Health and Medical Care Services Review, 1978; 1 : 1 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Cleary DC & Edgman‐Levitan S. Health Care Quality; Incorporating Consumer Perspectives. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1997; 278 (19) : 1608 1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, McHorney CA, Ware JE. Patients' ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1993; 270 (7) : 835 840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. McCusker J. Development of scales to measure satisfaction and preferences regarding long‐term and terminal care. Medical Care, 1984; 22 : 476 493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Brody DS, Miller SM, Lerman CE, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, Blum MJ. The relationship between patients' satisfaction with their physicians and perceptions about interventions. Medical Care, 1989; 27 : 1027 1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Cryns AG, Nichols RG, Kats LA, Calkins E. The hierarchical structure of geriatric patient satisfaction: An older patient satisfaction scale designed for HMOs. Medical Care, 1989; 27 : 802 816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]