Abstract

Therapy that promotes epithelial repair whilst protecting against fibroproliferation is critical for restoring lung function in acute and chronic respiratory diseases.

Primary human alveolar type II cells were used to model the effects of lipoxin A4 in vitro upon wound repair, proliferation, apoptosis and transdifferention. Effects of lipoxin A4 upon primary human lung fibroblast proliferation, collagen production, and myofibroblast differentiation were also assessed.

Lipoxin A4 promoted type II cell wound repair and proliferation, blocked the negative effects of soluble Fas ligand/tumour necrosis factor α upon cell proliferation, viability and apoptosis, and augmented the epithelial cell proliferative response to bronchoaveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In contrast, Lipoxin A4 reduced fibroblast proliferation, collagen production and myofibroblast differentiation induced by transforming growth factor β and BALF from ARDS. The effects of Lipoxin A4 were phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase dependent and mediated via the lipoxin A4 receptor.

Lipoxin A4 appears to promote alveolar epithelial repair by stimulating epitheial cell wound repair, proliferation, reducing apoptosis and promoting trans-differentiation of alveolar type II cells into type I cells. Lipoxin A4 reduces fibroblast proliferation, collagen production and myofibroblast differentiation. These data suggest that targeting lipoxin actions may be a therapeutic strategy for treating the resolution phase of ARDS.

Short abstract

Lipoxin A4 promotes epithelial repair while inhibiting fibroproliferation in vitro in human alveolar epithelial cells http://ow.ly/SxMu301cBRP

Lessons for clinicians

By promoting transdifferentiation of alveolar type II cells whilst inhibiting human lung fibroblast proliferation lipoxin A4 shows potential for a targeted rescue therapy in lung injury.

The replication of these experiments in epithelial-mesenchymal co-culture models as well as using lipoxin A4 receptor null mouse models of acute lung injury is essential for confirmation of these results.

This study has potential implications for developing therapies for preventing and treating the wide variety of lung diseses where fibroproliferation is a central part of the disease pathophysiology.

Introduction

Acute inflammatory lung diseases are often associated with epithelial cell loss due to apoptosis and fibro-proliferative responses. In acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), neutrophilic alveolitis results in significant alveolar epithelial cell injury and soluble Fas ligand (sFasL) mediated epithelial cell apoptosis [1]. The resolution phase of ARDS is believed to involve repair of the epithelial barrier by transdifferentiation of type II cells which have stem cell properties into type I epithelial cells [2], as well as alveolar bronchiolisation of epithelial cells from the distal airway [3]. The degree of alveolar epithelial injury is an important predictor of outcome [4]. In some cases of ARDS, a marked fibroproliferative response is seen which also negatively impacts on outcome [5]. Similarly, in chronic lung diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), there is lung epithelial cell loss due to apoptosis as well as fibroproliferation with the number of fibroblast foci relating to mortality [5]. Therefore, a therapy that promoted epithelial repair could be useful in both acute and chronic respiratory disease but only if it wasn't also a stimulus for fibro-poliferation.

Lipoxins (LXs) are unique structures derived from arachidonic acid [6]. They were the first mediators recognised to have dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution activities [7], with effects including the inhibition of neutrophil and eosinophil recruitment and activation [8], inhibition of fibroblast proliferation [9] and stimulation of macrophage clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in experimental ARDS [10]. LXs have been described as the endogenous “braking signal” for inflammation [7].

Previous studies have reported that LXA4 is able to attenuate airway inflammation [11]. LXA4 can promote wound healing and epithelial proliferation in the retinal epithelium [12] and can maintain the integrity of renal epithelia. Furthermore, LXA4 can regulate airway epithelial tight junction formation [13]. However, what is not known is whether LXA4 has a direct role in modulating adult human lung epithelial cell and primary human lung fibroblast proliferation and function. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that LXA4 acts both as a trophic factor for human adult type II alveolar lung epithelial cells, whilst inhibiting fibro-proliferation and reducing the effects of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) on primary human lung fibroblast (HLF) collagen production and myofibroblast differentiation.

Methods

Ethics

Lung tissue was obtained as part of the Midlands Lung Tissue Collaborative. All procedures in this study were carried out in accordance with approval from the local research ethics committees at the University of Birmingham (Birmingham, UK). All patients gave written informed consent for the use of their tissue and clinical data for research purposes.

Primary lung cell culture

Alveolar type II (ATII) cells were extracted from lung distal to the tumour in patients undergoing lung cancer resection. We used cells from 14 donors for ATII cell extraction who had normal lung function (eight male, six female, mean age 62.7 years). ATII cells were extracted according to methods described previously [14]. Average yields of primary human ATII cells were 30.2 million cells per resection with an average purity of 92% ATII-like cells (see online supplement). Primary HLF from Lonza (Tewkesbury, UK) were cultured in Dulbecco's media (ECACC; Sigma, Poole, UK). Experiments were repeated using cells from at least three separate donors.

Stimuli and inhibitors

ATII cells and fibroblasts were treated with LXA4 (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Appropriate vehicle controls were used for all experiments with inhibitors. Inhibitors were used at the following concentrations according to manufacturers' instructions: LY294002, a PI3-kinase inhibitor (Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK) at 10 µM; and the LXA4 receptor (ALXR) antagonist, BOC-2 (N-t-Boc-Phe-Leu-Phe-Leu-Phe; GenScript USA Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA), at 10 µM. Inhibitors were added to cells 1 h prior to every treatment.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collection

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from ARDS patients is known to stimulate epithelial repair in the scratch wound assay in an IL-1 dependent fashion [15]. To test whether LXA4 could augment or synergise with this effect, we used BALF from patients with ARDS patients mixed 50:50 with appropriate culture media for each cell type as a positive control stimulus. We used BALF from patients enrolled into the Beta Agonist Lung Injury Trial-1 (BALTI-1) trial, demographics for whom have been published previously [16].

In vitro alveolar epithelial wound repair assay

Epithelial repair was determined using an in vitro epithelial wound repair assay as described before [17]. To control for the inconsistencies in wound size, only monolayers in which the original wound areas varied by 10% of the mean were analysed.

Bromodeoxyuridine cell proliferation assay and cell viability assays

Bromodeoxyuridine (BRDU) incorporation was assessed according to manufacturers' instructions (BRDU Cell Proliferation Assay; Promega, Southampton, UK). Cell viability after 24 h was assessed adding 20 µL of Cell Titer 96 aqueous one solution cell proliferation solution (Promega) to cells after culture for 24 h as described [18].

Flow cytometry

Apoptosis of epithelial cells was assessed as described previously using flow cytometry [19].

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed using commercially obtained primers as outlined in supplementary methods

HLF proliferation assay in response to ARDS BALF

HLF were plated out at 2500 cells per well. A standard curve of cell counts was pipetted from 1250 to 15 000 per well. BALF mixed 50:50 with media was added from 10 ARDS patients. After 24 h BRDU incorporation was assessed as outlined above. Results were extrapolated from the standard curve. Each patient sample was run with six replicates upon a single batch of HLF at passage 3.

Statistical analysis

Data were normally distributed and analysed by analysis of variance with Tukey's test for post hoc comparisons using Minitab 14.0 (Minitab, State College, PA). A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean±sem.

Results

LXA4 stimulates ATII cell wound repair and proliferation in vitro

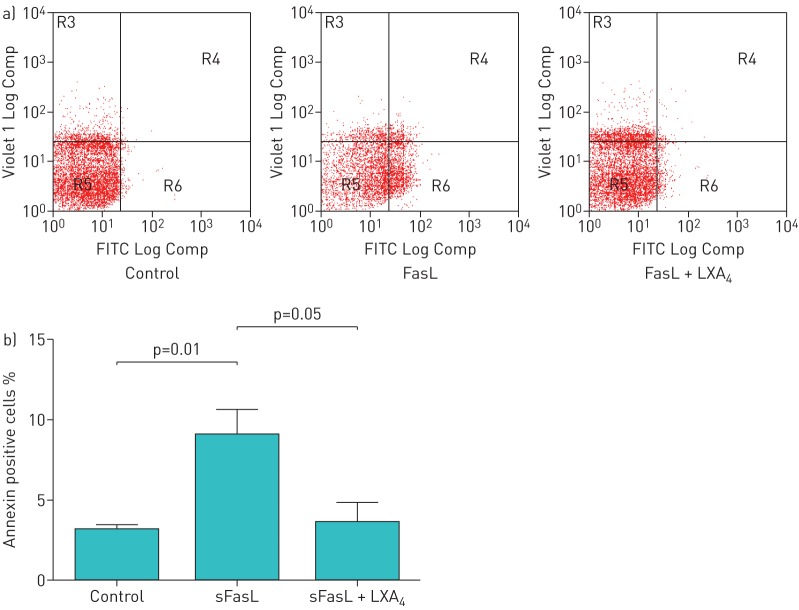

LXA4 increased ATII cell wound closure after 36 h compared with control media. ARDS BALF has previously been shown to promote epithelial wound repair [15] so we used ARDS BALF to model the stimulus to epthelial repair responses in ARDS. ARDS BALF increased ATII cell wound closure compared with media control. The combination of LXA4 and ARDS BALF enhanced the wound repair response (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of lipoxin A4 (LXA4) on alveolar type II cell (ATII) wound repair. LXA4 at different concentrations was added to monolayers of ATII cells physically wounded with a 1-mL pipette tip. To allow for variability between cell batches, data are expressed as the mean±sem percentage of the baseline wound size for each separate set of experiments for each culture condition of three independent experiments. ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; BALF: bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

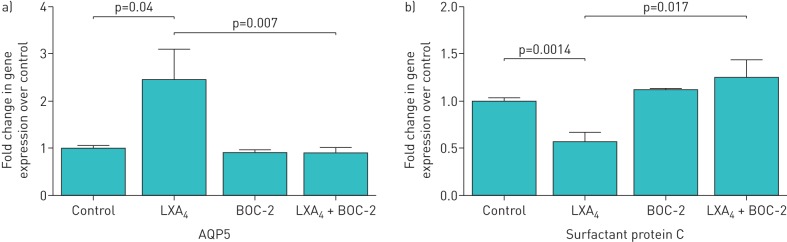

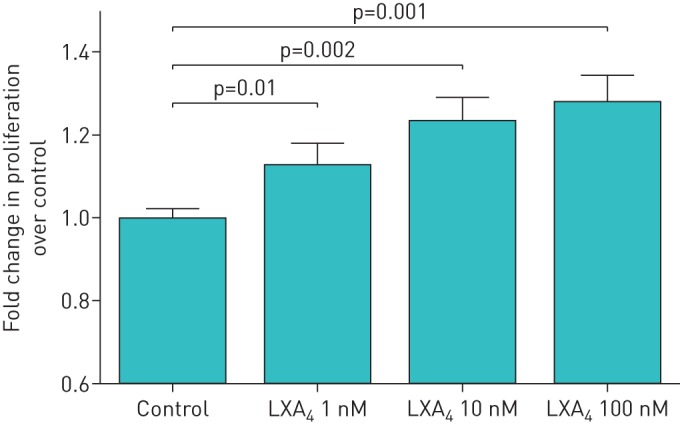

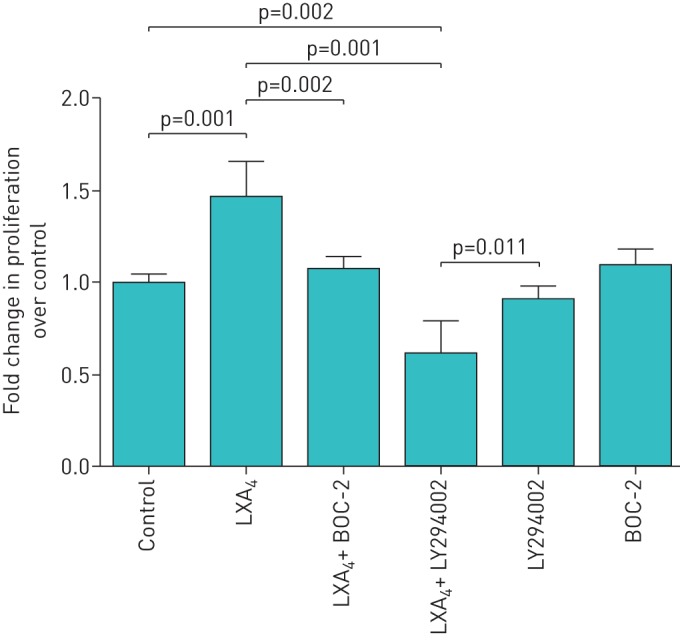

Scratch wound repair can occur due to either spreading of cells and/or proliferation. Cell proliferation studies confirmed that LXA4 stimulated proliferation of ATII cells in a dose-dependent manner (figure 2). To determine if PI3-kinase signalling is involved in the lipoxin proliferative response, LY294002 was incubated with ATII cells at 10 µM for 1 h before LXA4 treatment of ATII cells. LY294002 treatment reversed the effects of LXA4 (100 nM) on the proliferation of ATII cell compared with control media–treated cells (figure 3). Pre-treatment of cells with the LXA4 receptor (ALXR) antagonist, BOC-2, inhibited the effects of LXA4 on the proliferation of ATII cells (figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of lipoxin A4 (LXA4) on alveolar type II cell (ATII) proliferation. LXA4 stimulated the proliferation of primary human ATII cells. Values of >1-fold of control reflect increased proliferation. Data are presented as mean±sem of four independent experiments from four donors.

FIGURE 3.

Pro-proliferative effect of lipoxin A4 (LXA4) is phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase dependent and mediated by ALX/formyl peptide L1 receptor. 100 nM LXA4 promoted proliferation of alveolar type II cell (ATII) cells. Pretreatment with 10 µM LY294002, a phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase inhibitor, inhibited the effects of LXA4 on ATII cell proliferation suggesting that the pro-proliferation effects of LXA4 are phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase dependent. BOC-2, the formyl peptide receptor antagonist, was re-incubated with primary human ATII cells at 10 µM for 1 h before LXA4 treatment of ATII cells. BOC-2 treatment inhibited the effects of LXA4 on the proliferation of primary human ATII cells suggesting that the promoting proliferation effects of LXA4 are formyl peptide receptor dependent. Data are mean±sem of three independent experiments.

LXA4 protects against sFasL and tumour necrosis factor-α actions on ATII cells

sFasL and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibited cellular proliferation compared with control media–treated cells. This effect was attenuated by 100 nM LXA4 pretreatment (figure S1a). The addition of 100 ng·mL−1 sFasL and 100 ng·mL−1 TNF-α to ATII cells, as expected, significantly reduced cellular viability compared with control cells. Co-treatment with 100 nM LXA4 significantly increased cellular viability compared with sFasL and TNF combination (p=0.001) (figure S1b); an effect that was reduced by LXA4 rescue therapy added 30 min after treatment with sFasL (data not shown). sFasL treatment of ATII cells (which are known to be resistant to apoptosis) increased the number of apoptotic cells (annexin V+) from 2.61±0.53% in control cells to 9.04±0.94% (p=0.001). Rescue treatment with LXA4 reduced the number of apoptotic cells to 2.24±0.59% (p=0.001) (figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of lipoxin A4 (LXA4) on soluble Fas ligand induced annexin binding. a) Flow cytometry plots showing annexin binding. b) Flow cytometry analysis of annexin-positive cells 24 h after treatment with 100 ng·mL−1 soluble Fas ligand (sFasL). LXA4 at 100 nM reduced annexin binding.

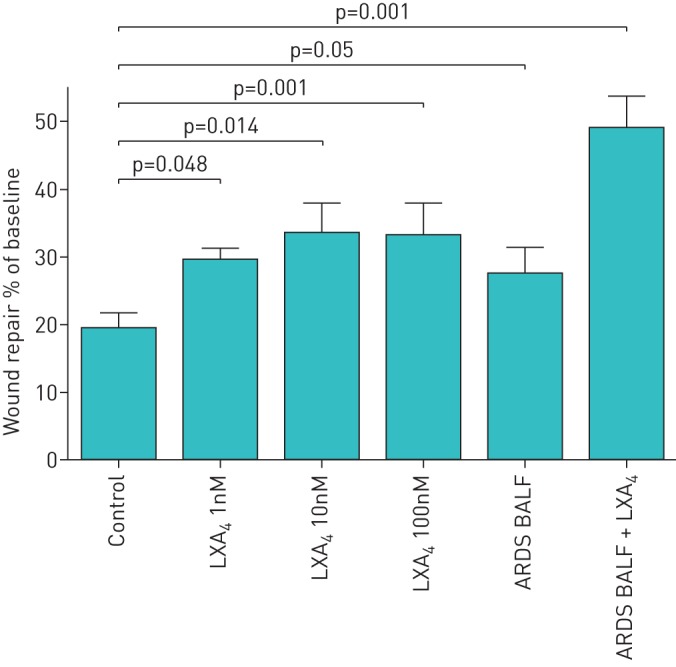

LXA4 promotes aquaporin 5 gene expression whilst reducing surfactant protein C gene expression by ATII cells

Aquaporin 5 (AQP5) is a membrane protein that mainly facilitates osmotic water transport that has been used as a type I epithelial cell marker [20, 21]. AQP5 may promote alveolar fluid clearance or maintain integrity of epithelial barrier [22]. Other roles for AQP5 have been explored in animal lung injury models, which show that lung injury is associated with a down-regulation of AQP5 expression [23, 24]. To determine whether LXA4 can promote AQP5 expression, ATII cells were treated by LXA4 for 24 h. LXA4 promoted AQP5 gene expression relative to control group (figure 5a). LXA4-induced AQP5 expression was blocked by the ALXR antagonist BOC-2 (figure 5a). In contrast LXA4 had no effect on the type I epithelial marker, receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (data not shown), but down-regulated mRNA expression of surfactant protein C (figure 5b), suggesting that LXA4 may promote transdifferentiation of ATII cells into ATI-like cells.

FIGURE 5.

Lipoxin A4 (LXA4) up-regulates aquaporin 5 (AQP5) and downregulates surfactant protein C but has no effect on receptor for advanced glycation end products. LXA4 promotes AQP5 gene expression while inhibiting surfactant protein C gene expression by primary human alveolar type II (ATII) cells. To determine whether LXA4 can affect AQP5 and surfactant protein C gene expression, ATII cells were treated by LXA4 for 24 h. a) AQP5 gene expression: LXA4 only (2.45±0.65 fold) relative to control group, p=0.004. The effect can be blocked by BOC-2 (formyl peptide receptor antagonist) (LXA4+BOC-2, mean, 0.89±0.12 fold, p=0.007). b) surfactant protein C gene expression: LXA4 only (0.57±0.10 fold) relative to control group, p=0.001. The effect can be blocked by BOC-2 (formyl peptide receptor antagonist) (LXA4+BOC-2, mean, 1.25±0.19 fold, p=0.01). Data are mean±sem of three independent experiments.

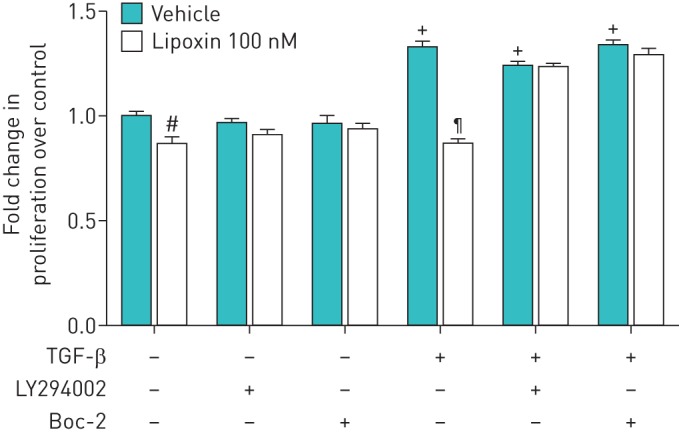

LXA4 inhibits proliferation of primary HLF induced by TGF-β and this effect is PI3-kinase dependent and blocked by BOC-2

Cell proliferation studies confirmed that 100 nM LXA4 inhibited proliferation of primary HLF induced by TGF-β. Cells were treated with TGF-β for 24 h with or without preincubation with the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 µM) or BOC-2 (10 µM). LXA4 inhibited the effects of TGF-β on HLF proliferation effects that were blocked by both LY294002 and BOC-2 (figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of lipoxin A4 (LXA4) on primary human lung fibroblast (HLF) proliferation in response to transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. Cell proliferation studies confirmed that LXA4 inhibited proliferation of primary HLF induced by TGF-β. Cultured and serum-deprived cells were treated with 1 ng·mL−1 TGF-β for 24 h with or without pre-incubation with LY294002 (10 µM) for 1 h, BOC-2 (10 µM) for 1 h. Data are mean±sem of three independent experiments. #: p=0.05; +: p=0.05, compared with no treatment group; ¶: p<0.01, compared with TGF-β only group.

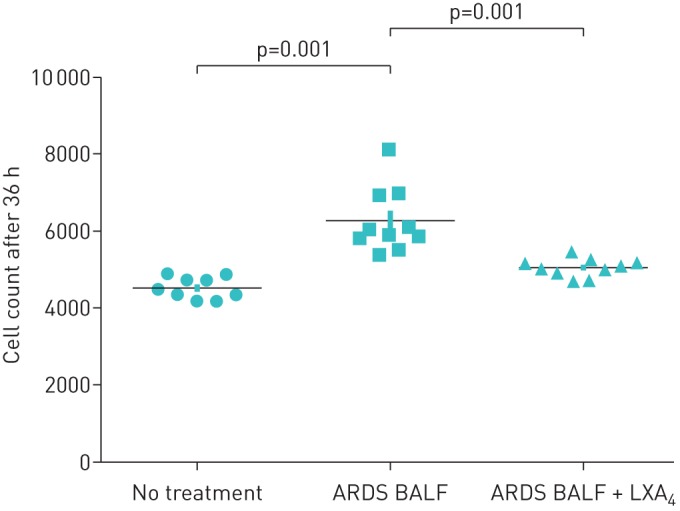

LXA4 inhibits proliferation of primary HLF induced by BALF from patients with ARDS

ARDS BALF has previously been shown to promote fibroblast proliferation in vitro [25]. To model the in vivo stimulus for fibroproliferation in ARDS, HLF were treated with a 50:50 mix of BALF from patients with ARDS. LXA4 inhibited ARDS BALF induced proliferation (figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of lipoxin A4 (LXA4) on primary human lung fibroblast (HLF) proliferation in response to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). BALF from patients with ARDS stimulated proliferation of primary HLF. LXA4 inhibited the proliferation of primary HLF induced by BALF from patients with ARDS. Data are mean±sem of three independent experiments.

LXA4 reduces primary HLF collagen production, N-cadherin, SLUG and α-smooth muscle actin induced by TGF-β and BALF from patients with ARDS

We investigated by quantitative PCR the mRNA expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, N-cadherin, SLUG (snail family transcriptional repressor 2) and α-SMA in HLF induced by TGF-β 10 ng·mL−1. Gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, α-SMA and N-cadherin were increased in HLF induced by 24 h of treatment with TGF-β relative to control group. LXA4 significantly inhibited gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, α-SMA and N-cadherin in HLF induced by TGF-β compared with TGF-β group respectively (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the different types of gene expression in response to treatment of different stimulations

| Gene type | TGF-β | LXA4 + TGF-β | BALF | LXA4 + BALF |

| Type I collagen | 323.35±168.07* | 14.87±7.53# | 9.47±3.78* | 5.69±2.77+ |

| Type IV collagen | 27.04±14.46* | 5.81±2.55# | 13.48±3.67* | 1.94±0.98++ |

| N-cadherin | 7.93±0.3** | 1.95±0.37## | 8.51±2.73* | 0.67±0.31++ |

| α-SMA | 22.36±2.93** | 7.24±0.62## | 4.01±1.05* | 1.34±0.62++ |

Data are presented as mean±sem fold change in gene expression over control. Lipoxin A4 (LXA4) reduces primary human lung fibroblast (HLF) collagen production, N-cadherin, SLUG and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) induced by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, α-SMA and N-cadherin were increased in HLF induced by TGF-β relative to control group. LXA4 significantly inhibited gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, N-cadherin and α-SMA in HLF induced by TGF-β compared to TGF-β group. Gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, SLUG and α-SMA and were increased in HLF induced by ARDS bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) relative to control group. LXA4 significantly inhibited gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, α-SMA and SLUG in HLF induced by BALF from patients with ARDS (compared to BALF group). Data are mean±sem of three independent experiments. *: p<0.05; and **: p<0.01 relative to control group, respectively; #: p<0.05, ##: p<0.01 compared with TGF-β group, respectively; +: p<0.05; and ++: p<0.01 compared with the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) group, respectively.

We also investigated the effect of ARDS BALF upon type I and IV collagen, α-SMA and SLUG mRNA expression. Gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen, α-SMA and SLUG were increased in HLF induced by ARDS BALF relative to control group (table 1). LXA4 significantly inhibited gene expression of type I and IV collagen, α-SMA and SLUG in HLF induced by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from patients with ARDS (table 1).

Discussion

This study provides evidence for a new mechanism by which LXA4 may contribute to alveolar repair; namely promoting physical wound closure by inducing proliferation of primary alveolar epithelial cells. We also demonstrate that LXA4 reduces ATII cells apoptosis induced by sFasL which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of ARDS. Intriguingly LXA4 also reduced fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation in response to TGF-β and ARDS BALF (as suggested by inhibiting collagen production and α-SMA expression) suggesting beneficial effects upon aberrant fibroproliferative responses.

Epithelial damage is a hallmark of ARDS [26] and LXA4 has been implicated in both anti-inflammatory actions on epithelial cells as well as promoting wound healing. LXA4 directly regulated several functional responses by the injured human bronchial epithelial cells, including inhibition of acid-induced IL-6 and promoting restitution of injured airway epithelium. In the cornea, LXA4 also stimulated corneal epithelial wound healing following eye injury [12, 27]. LXA4 has also been shown recently to stimulate alveolar fluid clearance by an effect upon epithelial sodium channel and sodium–potassium ATPases in experimental lung injury [28]. The role of lipoxin in apoptosis has been a matter of debate [29]. For instance, a pro-apoptotic effect upon renal interstitial fibroblasts after treatment with LXA4 has been described [30], whereas it promotes survival of retinal pigment epithelial cells as well as corneal epithelial cells [12, 31]. We therefore investigated the effects of LXA4 on physical wound repair, cellular proliferation, and apoptosis in ATII cells which are responsible for repair after lung injury.

LXA4 increased ATII cell wound repair and proliferation and our study also shows that the mitogenic response of ATII cells to LXA4 is mediated via activation of ALX/formyl peptide receptor (FPR)-2 receptor. Furthermore, LXA4 inhibited apoptosis and reduced cell death in sFasL/TNF-α treated cells even when given after the onset of injury and, therefore, has potential as a rescue therapy.

The repair of the alveolar epithelium following injury is believed to involve the transdifferentiation of ATII cells into type I cells. LXA4 increased expression of AQP5 (type I marker) but not RAGE in ATII via activation of ALX/FPLR-1 supporting a potential role for LXA4 in promoting fluid transport. LXA4 treatment reduced expression of surfactant protein C (type II markers) in vitro suggesting that it may promote transdifferentiation of ATII cells towards the ATI phenotype. The role of Lipoxin in cell proliferation, migration and would repair has also been documented in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cell lines [32]. Moreover, LXA4 has also been reported to slow mouse fibroblast migration and scratch wound closure [2].

Recent data have demonstrated an aspirin-triggered LXA4-reduced inflammation and fibrosis in murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis [33]. Further up-regulation of the LXA4 receptor in vivo is associated with reduced collagen accumulation in the bleomycin-induced model of lung fibrosis [34]. Recent data also suggest human mesenchymal stem cells promote the resolution of acute lung injury in part through LXA4 signalling via formyl peptide receptor 2 (ALX/FPR) [35]. We demonstrated that LXA4 inhibited TGF-β induced proliferation in primary HLF via activation of ALX/FPLR-1 and was mediated via activation of the PI3/Akt signalling pathway. This result is in agreement with previously reported evidence that LXA4 inhibited the proliferation of HLF cell line evoked by connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) [9].

It is established that, as fibroblasts differentiate to myofibroblasts in response to TGF-β, there is up-regulation of levels of α-SMA and a markedly enhanced ability to secrete extracellular matrix proteins [36, 37]. Our data show LXA4 significantly inhibits gene expression of type I collagen, type IV collagen and α-SMA in HLF induced by TGF-β. We also demonstrate for the first time that ARDS BALF stimulated the expression of markers of myofibroblast differentiation when incubated with normal HLF; an effect that was blocked by LXA4. Our data therefore suggest that LXA4 has differential effects upon ATII and HLF cells in vitro; both promoting epithelial repair whilst reducing fibroproliferation. This differential effect is potentially vitally important for LXA4 and its more stable analogues to be use as novel therapies in both acute and chronic inflammatory lung diseases.

Limitations

This study has limitations: we have been unable to assess levels of LXA4 in patient samples due to the lack of reliable ELISA assays for the analysis. There is little information about LXA4 in patient samples with sepsis and ARDS and this is something that should be addressed. However, recently LXA4 levels have been reported to be lower in patients with sepsis [38]. Similarly, we lack tissue from patients with ARDS to test whether ALX receptor expression is altered in ARDS.

Further, our assessments of ATII/ATI and fibroblast/myofibroblast phenotypes are dependent upon quantitative PCR rather than protein expression but are consistent with reported effects in other tissues. Quantification of additional cell type markers at the protein level correlating with morphological features in the in vitro cultured cells would be useful to support transdifferentiation of ATII cells. However, the study of ATII cell biology is restricted by lack of specific markers. Surfactant protein expression has been widely used as a definitive marker to identify type II cells; likewise, aquaporin 5 as marker for type I cells. Unfortunately, we are unable to retrospectively analyse further markers owing to lack of frozen cells from the same batches as used in the marker analysis in this study.

Flow cytometry analysis for CD208, a member of the lysosomal-associated membrane protein family and a marker of normal ATII cells, would supplement the pro-transdifferentiation role of lipoxin at the protein level. Also given the importance of the effect of co-culture of epithelial cells with mesechymal cells in ligand responsiveness [39] it will be important to address these issues in human three-dimensional co-culture models. Furthermore, future experiments will have to substantiate results of this study using wild type and FPR null mouse model of ALI. In addition, as LXA4 has a shorter half-life in vivo, experiments using stable analogues that have greater efficacy is vital to establish its functional role. There is recent evidence that a stable epi-LXA4 analogue reduced bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice [33] supporting a role for LXA4 as a potential treatment for lung injury/fibrosis. Additionally, a recent study has reported that resolvin D2 which is more stable than LXA4, and activates similar receptors demonstrating similar effects on fibroblast migration and proliferation [40].

In conclusion, the results from our study demonstrate that LXA4 increased wound repair and proliferation of primary human ATII cells in vitro. LXA4 protected ATII cells from pro-apoptotic stimuli even when given after the initial injury. LXA4 promoted the expression of the type I marker, AQP5, with reduction in surfactant protein C by ATII like cells potentially promoting transdifferentiation- an important part of repair after alveolar injury. Since the restoration of a confluent alveolar epithelial cell barrier is a critical aspect of alveolar repair, for which there is no targeted rescue therapy currently available [8], we believe that LXA4 has therapeutic potential for the ARDS which is associated with significant alveolar epithelial damage.

We have also demonstrated that LXA4inhibited HLF proliferation, HLF collagen production and α-SMA expression in response to both TGF-β and ARDS BALF. As it stands, the function of LXA4 is not fully charecterised in alveolar epithelial cells and in lung fibrosis. Besides, these results are novel and interesting for the reason that primary human lung cells often respond very differently to animal models.

These data have important implications for future efforts in developing an efficient therapeutic strategy for preventing and treating the fibroproliferative phase of ARDS as well as chronic diseases such as IPF by targeting LXA4 actions. Further experiments are necessary to understand the basic mechanism underlying the anti-fibrotic effects of LXA4, which are currently under investigation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and relatives who agreed to both tissue donation during elective surgery and participation in translational studies when in intensive care. We would like to thank Teresa Melody and Dawn Hill as nurse/coordinator (both Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK).

Author Contributions: David R. Thickett, Fang Gao-Smith, Qingquan Lian and Shengwei Jin participated in the concept and design of the study. Shengxing Zheng, Vijay K. D'Souza, Domokos Bartis, Rachel C.A. Dancer, Babu Naidu, Dhruv Parekh and Qian Wang carried out cell preparation, laboratory work and data analysis. David R. Thickett, Shengxing Zheng, Vijay K. D'Souza, Babu Naidu, Fang Gao-Smith, Qian Wang, Dhruv Parekh and Domokos Bartis helped to draft the manuscript. Shengxing Zheng is the guarantor of the data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

Support statement: D.R. Thickett was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Wellcome Trust. D. Bartis was funded by a European Respiratory Society long-term training fellowship. D. Parekh and R.C.A. Dancer were funded by the MRC. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81070061, 81270132 and 81401579) and the Zhejiang Provincial Program for the Cultivation of High-level Innovative Health Talents. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Open Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Parekh D, Dancer RC, Thickett DR. Acute lung injury. Clin Med 2011; 11: 615–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Rackley CR, et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 3025–3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thickett DR, Poole AR, Millar AB. The balance between collagen synthesis and degradation in diffuse lung disease. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2001; 18: 27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthay MA, Robriquet L, Fang X. Alveolar epithelium: role in lung fluid balance and acute lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005; 2: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin C, Papazian L, Payan MJ, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis correlates with outcome in adult respiratory distress syndrome. A study in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest 1995; 107: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn H, O'Donnell VB. Inflammation and immune regulation by 12/15-lipoxygenases. Prog Lipid Res 2006; 45: 334–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 349–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filep JG, Zouki C, Petasis NA, et al. Anti-inflammatory actions of lipoxin A(4) stable analogs are demonstrable in human whole blood: modulation of leukocyte adhesion molecules and inhibition of neutrophil-endothelial interactions. Blood 1999; 94: 4132–4142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu SH, Wu XH, Lu C, et al. Lipoxin A4 inhibits proliferation of human lung fibroblasts induced by connective tissue growth factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006; 34: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reville K, Crean JK, Vivers S, et al. Lipoxin A4 redistributes myosin IIA and Cdc42 in macrophages: implications for phagocytosis of apoptotic leukocytes. J Immunol 2006; 176: 1878–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin SW, Zhang L, Lian QQ, et al. Posttreatment with aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 analog attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice: the role of heme oxygenase-1. Anesth Analg 2007; 104: 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenchegowda S, Bazan HE. Significance of lipid mediators in corneal injury and repair. J Lipid Res 2010: 51: 879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grumbach Y, Quynh NV, Chiron R, et al. LXA4 stimulates ZO-1 expression and transepithelial electrical resistance in human airway epithelial (16HBE14o-) cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009; 296: L101–L108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKeown S, Richter AG, O'Kane C, et al. MMP expression and abnormal lung permeability are important determinants of outcome in IPF. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins GD, Gao F, Thickett DR. In vivo and in vitro effects of salbutamol on alveolar epithelial repair in acute lung injury. Thorax 2008; 63: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkins GD, McAuley DF, Thickett DR, et al. The beta-agonist lung injury trial (BALTI): a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiser T, Ishigaki M, van Leer C, et al. H2O2 inhibits alveolar epithelial wound repair in vitro by induction of apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004; 287: L448–L453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zolnai A, Tóth EB, Wilson RA, et al. Comparison of 3H-thymidine incorporation and CellTiter 96 aqueous colorimetric assays in cell proliferation of bovine mononuclear cells. Acta Vet Hung 1998; 46: 191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter AG, McKeown S, Rathinam S, et al. Soluble endostatin is a novel inhibitor of epithelial repair in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 2009; 64: 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verkman AS, Matthay MA, Song Y. Aquaporin water channels and lung physiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000; 278: L867–L879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins G, Blanchard A, Borok Z, et al. In search of the fibrotic epithelial cell: opportunities for a collaborative network. Thorax 2012; 67: 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King LS, Nielsen S, Agre P. Respiratory aquaporins in lung inflammation: the night is young. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000; 22: 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song Y, Fukuda N, Bai C, et al. Role of aquaporins in alveolar fluid clearance in neonatal and adult lung, and in oedema formation following acute lung injury: studies in transgenic aquaporin null mice. J Physiol 2000; 525: 771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towne JE, Harrod KS, Krane CM, et al. Decreased expression of aquaporin (AQP)1 and AQP5 in mouse lung after acute viral infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000; 22: 34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall RP, Bellingan G, Webb S, et al. Fibroproliferation occurs early in the acute respiratory distress syndrome and impacts on outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162: 1783–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gropper MA, Wiener-Kronish J. The epithelium in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care 2008; 14: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gronert K. Lipoxins in the eye and their role in wound healing. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2005; 73: 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Lian QQ, Li R, et al. Lipoxin A(4) activates alveolar epithelial sodium channel, Na,K-ATPase, and increases alveolar fluid clearance. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013; 48: 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serhan CN, Brain SD, Buckley CD, et al. Resolution of inflammation: state of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J 2007; 21: 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu SH, Lu C, Dong L, et al. High dose of lipoxin A4 induces apoptosis in rat renal interstitial fibroblasts. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2005; 73: 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calandria JM, Marcheselli VL, Mukherjee PK, et al. Selective survival rescue in 15-lipoxygenase-1-deficient retinal pigment epithelial cells by the novel docosahexaenoic acid-derived mediator, neuroprotectin D1. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 17877–17882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins G, Buchanan P, Perriere M, et al. Activation of P2RY11 and ATP release by lipoxin A4 restores the airway surface liquid layer and epithelial repair in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 51: 178–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martins V, Valenca SS, Farias-Filho FA, et al. ATLa, an aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 synthetic analog, prevents the inflammatory and fibrotic effects of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 2009; 182: 5374–5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato Y, Kitasato H, Murakami Y, et al. Down-regulation of lipoxin A4 receptor by thromboxane A2 signaling in RAW246.7 cells in vitro and bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in vivo. Biomed Pharmacother 2004; 58: 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang X, Abbott J, Cheng L, et al. Human mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells promote the resolution of acute lung injury in part through lipoxin A4. J Immunol 2015; 195: 875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurent GJ, McAnulty RJ, Hill M, et al. Escape from the matrix: multiple mechanisms for fibroblast activation in pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008; 5: 311–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caraci F, Gili E, Calafiore M, et al. TGF-beta1 targets the GSK-3beta/beta-catenin pathway via ERK activation in the transition of human lung fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Pharmacol Res 2008; 57: 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai WH, Shih CH, Yu YB, et al. Plasma levels in sepsis patients of annexin A1, lipoxin A4, macrophage inflammatory protein-3a, and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Chin Med Assoc 2013; 76: 486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartis D, Mise N, Mahida RY, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung development and disease: does it exist and is it important? Thorax 2014; 69: 760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrera BS, Kantarci A, Zarrough A, et al. LXA4 actions direct fibroblast function and wound closure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015; 464: 1072–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]