Abstract

Linkage to and retention in medical care is a concern for HIV-positive individuals leaving custody settings in the United States. The minimal existing research points to low rates of entry into care in the months following release and lapsed viral control among releasees who are subsequently reincarcerated. We conducted seven small focus group discussions with 27 HIV-positive individuals who were recently incarceration in a California State prison to understand those factors that facilitated linkage to and retention in HIV care following their release. We used a consensual approach to code and analyze the focus group transcripts. Four main themes emerged from the analysis: 1) interpersonal relationships, 2) professional relationships, 3) coping strategies and resources, and 4) individual attitudes. Improving HIV-related outcomes among individuals after their release from prison requires strengthening supportive relationships, fostering the appropriate attitudes and skills, and ensuring access to resources that stabilize daily living and facilitate the process of accessing care.

Keywords: Prison, HIV, Medical Engagement, Predictors, Facilitators

Introduction

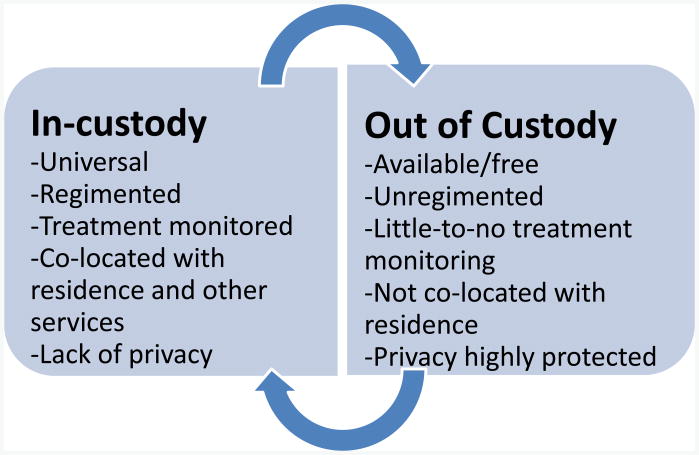

Roughly 1 in 7 individuals living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are estimated to leave a correctional facility each year (Spaulding et al., 2009). These facilities include state and federal prisons that hold those sentenced to longer terms and jails that hold those awaiting trial or sentenced to shorter terms. Prison settings are more structured and stable than jail settings and individuals released from prison may spend more time under community supervision (e.g., parole) than those released from jail. HIV prevalence is nearly 2.4 times greater in the incarcerated population than in the general population (Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2013). Jails and prisons provide care to a population that outside of custody may have little engagement with health care systems because of its frequently poor socioeconomic status and avoidance of preventive measures (Lines, 2006). During incarceration, prisoners have a constitutionally protected right to receive health care (Lines, 2006; Wilper et al., 2009). On leaving incarcerated settings, HIV-positive individuals exit one system of care for a second system with very different characteristics and requirements of its patients (see Figure 1). The contrast between prison-and community-based health systems and the multiple stigmas that they face -- both as recently incarcerated people with HIV and frequently as sexual and/or racial minorities -- may leave them poorly equipped to manage the complexities of navigating HIV care in the general community.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of in-custody and general community (out-of-custody) HIV care systems in the United States.

Persons with histories of incarceration report elevated rates of HIV risk behaviors, including substance abuse, multiple sex partners, and exchange of sex for money or drugs (MacGowan et al., 2003; Stephenson et al., 2006), and low socioeconomic status indicators. Furthermore, HIV-positive prisoners are more likely to have a history of mental illness than are HIV-negative prisoners (Baillargeon et al., 2008), and both substance use disorders and mental illness can impede HIV treatment adherence (Gonzalez, Barinas, & O'Cleirigh, 2011; Rosen et al., 2013). Hence, incarcerated persons who are living with HIV often experience comorbidities, intense socioeconomic needs, and potential high risk for HIV progression and transmission. Without adequate engagement with appropriate medical and social services for this population during reentry to society, their health and the health of the communities they return to can be negatively impacted (Davis et al., 2009).

The existing research points to low levels of HIV treatment continuation among HIV patients post release from prison (Harzke, Ross, & Scott, 2006; Palepu et al., 2004; Springer et al., 2004; Wohl et al., 2011). For example, Baillargeon et al.'s study of medication access among 2,115 HIV-positive individuals leaving Texas prisons found that only 30% had obtained antiretroviral medications within 60 days of release (Baillargeon et al., 2009). Having been released on parole and having received assistance with completing AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) applications were positively associated with medication acquisition (Baillargeon et al., 2009). In a related Harris County, Texas study, just 28% of 1,750 HIV-positive patients enrolled in HIV care within the 90 days following release (Baillargeon et al., 2010). Older age, receipt of discharge planning, and a prior diagnosis of schizophrenia were positively associated with enrollment. A small, underpowered Texas study showed evidence of positive associations between stable housing, satisfactory housing, and the provision of HIV medications at release with post-release linkage to HIV primary care (Harzke et al., 2006). In addition, two studies of have shown positive associations between medical care engagement and a depression diagnosis (Fox et al., 2014; Wohl et al., 2011), perhaps because former prisoners with comorbid mental illness have multiple reasons to engage in care and multiple entry points to medical care. Nevertheless, most studies find that untreated depression is negatively associated with HIV medication adherence (Blashill, Perry, & Safren, 2011; Kumar & Encinosa, 2009).

To our knowledge, only three published studies, all conducted in the US, have used qualitative approaches to describe facilitators and barriers to engaging in HIV care post incarceration. A South Florida focus group study of 20 persons released from jail in the prior 12 months found that concerns regarding HIV stigma and medication side effects, limited transportation access, and pessimism regarding HIV treatment were frequent barriers; whereas client confidentiality, access to low-/no-cost medical services, pleasant HIV care providers, and short weight times facilitated care. Furthermore, participants' educational level, spirituality, and desire to stay healthy for their families motivated them to engage in care (Fontana & Beckerman, 2007). During in-depth interviews with 20 clients of a Rhode Island linkage-to-care demonstration project mental illness, substance abuse, and unstable housing were described as the primary challenges to successful linkage to HIV medical care (Nunn et al., 2010). A recent North Carolina-based study involved in-depth interviews with 20 prisoners at pre-release, of whom 13 were interviewed up to one year following release. Despite personal motivations and prior confidence in their ability to obtain treatment, half did not engage in care within four weeks of release. Competing needs (particularly housing and employment), chaotic life circumstances, and substance abuse relapse frequently deterred participants', as did their multiple experiences of perceived and enacted stigma (Haley et al., 2014).

These studies highlight the multiple challenges to engaging in care that HIV-positive reentry populations face and qualitative research's role in examining these complex issues while elucidating potential points of intervention. The research represents just four U.S. states and does not include California. The experiences of HIV-positive former prisoners in the Los Angeles warrant specific study. California has-- the nation's second largest prison system (Evans & Tinsley, 2012) and Los Angeles is a large urban HIV epicenter where the first AIDS cases were identified; hence HIV-related awareness and stigma may differ. Hence, the experiences of HIV-positive former prisoners in the County warrant specific study. Furthermore, despite what has been learned from these studies, the only published randomized trial to date of an intervention to promote care engagement did not show efficacy (Wohl et al., 2011)

We conducted seven focus groups with HIV-positive individuals who had been released from a California state prison (run by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation or CDCR) in the prior 24 months. At the time of the study, all individuals sentenced to a year or more of state prison time were mandated to CDCR facilities. Our study aims to increase our understanding of what contributes to HIV medical care engagement in former prisoners. Therefore, we highlight factors that participants described as supporting linkage to and retention in HIV-related care and that can be built upon and fostered in future interventions for formerly incarcerated individuals who are living with HIV.

Methods

Focus Group Discussion Guide

A structured guide, covering issues pertaining to prisoner re-entry and engagement in HIV specific medical care, was developed independently by the four-member research team. The group then formulated these issues into questions and presented them to a community advisory board (CAB) comprised of service providers and formerly incarcerated individuals for their input. The revised discussion guide was implemented with the first focus group and subsequently revised based on that group experience and transcript review. Some examples of final questions are, “Before you were released from prison, were you provided with any information or service that helped with your return to your community? Describe what is involved in obtaining medical care for people after release.… What is it like for people to get housing upon their release? What worked and didn't work with your housing? What resources did you find useful to help you with housing? What type of housing helps you the most with being stable?”

Recruitment and Enrollment

Recruitment was carried out between October 2012 and October 2013 by distribution and posting of flyers and through CAB member and provider referrals. Outreach sites included HIV clinics, housing facilities targeting the formerly incarcerated, substance abuse treatment centers, parole offices, and HIV educational events. Potential participants called the study number and were screened by a series of questions to determine their eligibility (i.e., a diagnosis of HIV, age 18 years or older, and incarceration in a California state prison in the prior 24 months). Of the 59 persons screened, 43 (73%) met the eligibility criteria, of whom 27 (63%) both scheduled and kept their appointments. Among those who were study eligible, there were no statistically significant differences between participants and non-participants did not differ significantly in their race/ethnicity, age, HIV care status, length of time since last incarceration, or recruitment source. They did differ by sex, with none of three eligible females participating, compared with 68% of the eligible males. Participants provided documentation of their HIV status and were compensated $40 for participation.

A total of seven focus group discussions and 27 participants are represented in our qualitative data summary and analysis (see Table 1). Focus groups were scheduled once at least four eligible individuals had committed to attend. However, poor attendance resulted in only two participants for two of the focus groups (range = 2-6 participants). Due to a technical difficulty with our recording device, only about half (55 minutes) of the recording from Group #2 discussion was analyzable. Saturation was reached with these seven groups.

Table 1. Recruitment sources, background characteristics of HIV-positive former prisoners.

| Referred by: | n=27 |

| Community Liaison/Recruiter | 15 (55%) |

| Flyer | 5 (19%) |

| Friend | 3 (11%) |

| Case Manager | 1 (4%) |

| Mental Health Counselor | 1 (4%) |

| Unknown | 2 (7%) |

|

| |

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | n=27 |

| Age | |

| < 30 | 1 (4%) |

| 30-39 | 3 (11) |

| 40-49 | 15 (55) |

| 50+ | 8 (30) |

| Race | |

| Black | 23(85) |

| Latino | 3 (11) |

| White | 1 (4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 26 (96%) |

| Female | 0 |

| Transgender (MtF) | 1 (4) |

| Date last released from incarceration | |

| <1 month prior | 1 (4%) |

| 1-3 months prior | 3 (11) |

| 4-12 months prior | 10 (37) |

| 13-24 months prior | 12 (44) |

| Missing | 1 (4) |

| Time since first HIV diagnosis | |

| < 2 years | 1 (4%) |

| 2-4 years | 3 (11) |

| 5-9 years | 8 (30) |

| 10 or more years | 10 (55) |

| Time to first HIV linkage post release (most recent incarceration) | |

| <30 days | 22 (81%) |

| 30-90 days | 0 |

| More than 90 days | 0 |

| Not yet linked (after 84 to 484 days) | 5 (19) |

| State prison last released from | |

| California Institute for Men -Chino | 9 (33%) |

| California Rehabilitation Center- Norco | 7 (26) |

| California Men's Colony (CMC) | 3 (11) |

| California State Prison - Corcoran | 2 (7) |

| California State Prison - Lancaster | 2 (7) |

| R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility - Rock Mountain | 1 (4) |

| High Desert State Prison - Susanville | 1 (4) |

| California State Prison - Sacramento | 1 (4) |

| Unknown | 1 (4) |

Study Participants

The participants are described in Table 1. The majority were men (94%), Black/African American(85%), and 40 years of age or older (72%). They indicated having been last housed in 8 of the 34 adult state prison facilities located throughout California. More than half (n=15) had learned of the study from our research assistant (a former prisoner who had provided peer support services to some of these individuals). A few focus group members knew one another prior to their group participation, either because one referred the other to the project or because they had received HIV services in the same settings.

Focus Group Format

The focus group discussions were conducted in a confidential room at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science. One of the Principal Investigators, a licensed clinical psychologist, served as the facilitator. Two research assistants took posted process notes and notes of non-verbal observations during the focus groups. One of the focus groups with two participants lasted just 70 minutes. The remaining six groups lasted between 100 and 130 minutes.

Qualitative Data Coding and Analysis

We employed a consensual qualitative research approach (Hill, Thompson, & Nutt Williams, 1997). We used open coding to develop codes and later conducted axial coding to relate these codes to one another and to identify major themes. To begin, all four members of the research team individually developed codes based on their readings of two group transcripts and using the five broad Discussion Guide categories (barriers, protective/facilitating factors, individual background characteristics, internal motivators, and external motivators to HIV retention and care) as a framework. Next, the research team met to discuss each member's chosen codes and develop a first draft codebook. Two sets of two-member teams then each separately coded the five transcripts using Atlas.ti and the preliminary codebook. After each transcript was coded, the entire research team again met to discuss and reach consensus with regard to each coded quotation and any new codes proposed. The final two transcripts were coded by one team member and reviewed by a second, with all points of disagreement discussed with the full team. This process led to the addition of new codes, the elimination or combination of some existing codes, as well as the refinement of many code definitions (total codes = 54).

Next, we used Atlas.ti query tool to count the number of different quotes associated with each code across transcripts (range = 0-46). Because we were interested in issues that might impact a substantive proportion of the target population, we focused on more frequently identified codes, assigning all codes with at least 11 quotes to different team members to review and summarize their prevailing themes. The full team again undertook an iterative process of review and discussion regarding how the themes and codes related to the five broad Discussion Guide categories, resulting in some consolidation and a final list of highly relevant codes and themes. They then also discussed each of the less frequently mentioned codes and determined its importance in relation to the study aims–taking into account codes for factors that appeared to strongly impact those who discussed them. The iterative analysis process led to 26 major codes encompassing four overarching themes that had a positive impact on care engagement: supportive personal relationships, productive professional relationships, coping strategies and resources, and individual attitudes. Participant quotes in this article are labeled by both a focus group number and a pseudonym.

Results

Below, we describe specific factors within four overarching themes of factors that facilitated the participants' linking to HIV medical care and attending medical appointments, accessing and adhering to antiretroviral treatment regimens, and avoiding recidivism post-release from custody.

Supportive Personal Relationships

In response to our asking participants directly about the support received from friends and family upon release from prison, they generally referred to their local friends, their families of origin, and their children. A few also described having formed family bonds with individuals to whom they were not related by blood or marriage. Some also discussed roles played by their significant others; however, they only talked about female significant others in this context. The nature of the support received varied according to these three relationship types.

Friends

Emotional support, appropriate guidance and a willingness to talk to others positively about the participant were noted as particularly important aspects of the support received from friends. This guidance and advocacy sometimes led to social services or other opportunities (e.g., employment) but rarely contributed directly to participants' receipt of medical care or adherence. Other roles played by friends included guarding individuals' possessions during their incarcerations or providing shelter on release, thus helping them reintegrate into society.

Family members

Participants did describe having family members who provided direct support for coping with HIV disease. This included HIV-positive family members who shared their knowledge and experiences and other family members who sought to learn about HIV in response to the participant's HIV disclosure. These and other family members provided emotional support and encouragement for living with HIV. Most commonly, however, participants' families were the major providers of instrumental support, including housing, transportation, clothing, meals, and more rarely, cash. Furthermore, participants' connections to their families motivated several to remain/become adherent to their medications and avoid re-incarceration. Typically younger sons/daughters, nieces/nephews, and grandchildren inspired these participants to remain healthy and avoid re-incarceration so that they could see them grow and accomplish life milestones. Here Rich refers to his pregnant daughter:

‘She's 19. So she'll be having a baby next month. So, I kind of use that more as motivation to go ahead and take the pills so that I could live-- try to live as long as possible for the baby and for my daughter and for when the baby grows up.’ – Rich, Group 4

The importance of staying engaged in family members' lives was underscored a number of participants who mentioned having mothers who had died during their long prison terms.

Significant others

Significant others were mainly described as providing support and acceptance of the participants' HIV diagnoses. These partners were comfortable around people with HIV/AIDS and frequently knowledgeable about HIV -- sometimes a stark contrast to the respondents' experiences with others in the community and in custody, where enacted HIV stigma could be particularly intense. Partners' closeness to participants and awareness of their HIV status also allowed them to encourage medication adherence:

“We are soul mates. So to me to have somebody in my life that I don't have to hide no more, I don't have to sneak and take my medication or none of that… She's more on me, ‘Did you take them?’” Chris, Group 4

Significant others also provided general emotional support by caring for the participants, giving them hope, and sometimes helping them to address substance abuse and dependence.

Productive Professional Relationships

The three main types of professional relationships reported as influencing care engagement were those with HIV medical providers, social service providers, and peer advocates. Participants were also asked about the influence of parole officers, as many were under criminal supervision. Hence, they had parole officers (or in some cases probation officers) who yielded a tremendous amount of power over whether or not they remained in the community rather than being remanded to custody. Nevertheless, only one individual indicated that his officer encouraged him to be consistent in his HIV care and other participants characterized these officers as disengaged from former prisoners' medical issues.

HIV medical providers

Those participants who were currently engaged in care tended to have a personal rapport with their medical providers and could voice to them their concerns and opinions about their emotional wellbeing, as well as their medical conditions. Participants who did not report this type of connection often reported losing focus and withdrawing from regular HIV care. Participants preferred HIV providers who recommended specialized treatments and explained details of their condition but allowed them to make their own decisions about courses of treatment. This empowered participants, creating a sense of partnership and respect, as described by Darnell who initially wanted to treat his HIV infection through diet rather than medication:

“Well, you know what? I had one doctor, we sat down, and we agreed that to give me 30 days on nutritional therapy, [and then] ‘come back, take a lab test.’ And if I got better, then we would try to - he would try to support that. If not, then I would take the medication.”- Darnell, Group 1

Participants also favored physicians who were truthful and matter of fact: “I don't want to deal with anybody who's going to tell me what I want to hear and send me out of their face.” Similarly, several responded positively to “tough love” interactions and to personal words of encouragement from their providers, as in this powerful exchange that helped Barnes to shift from depression and despair over his diagnosis to acceptance and a desire to help others:

“He said, ‘Can I ask you a question?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He says, ‘Can I pray for you? Do you mind me praying for you?’ I said, ‘No, go ahead.’ And so he prayed for me, man. And then he looked back at me, he says, ‘Man, you need to get up out this bed because if you don't, this bed is going to kill you … I was like rotting away.’” – Barnes, Group 5

Social service providers

Interestingly, although participants never questioned the competence of their HIV medical providers, they frequently questioned the competence of social service providers, or they emphasized the importance of finding a competent, committed case manager. Case managers and social workers were often praised for their role in helping to stabilize life circumstances and secure needed services. Participants most recognized those providers who showed a determination to help them attain what they needed and a deep knowledge of and connections to those locally available services that their post-incarcerated clients were eligible to receive. Former prisoners' ineligibility for many government benefits and participants' experiences of following the directions of less-effective social service providers, only to be denied services, highlighted the importance of these qualities in their providers. Participants also noted that the service agency environment influenced the quality of the services they received -- characterized some agencies as fostering high standards and being responsive to client concerns and others as the opposite, leading them to feel ostracized by some providers if they lodged a complaint.

Peer advocates

Information about both positive and negative experiences with providers and agencies was often shared through patient and social networks, including HIV support groups. Hence, personal relationships with other people living with HIV not only influenced care engagement but also the specific relationships that formed between patients and providers. In addition to these informal interactions with other patients, participants described benefitting from trained peer advocates who had a wide range of knowledge about service agencies and providers, provided up-to-date treatment information, and modeled how to address HIV stigma. These peer advocates encouraged individuals to explore available treatment options, possessed a passion to help, were always truthful, and empathized with participants.

Coping Strategies and Resources

Participants drew on a wide range of coping strategies, knowledge, and resources in order to handle reentry challenges and to manage their HIV-related care.

Coping strategies

Participants frequently discussed their strategies for dealing with a broad range of life challenges, including addiction, relationships, and securing resources and services. They described engaging self-management techniques to minimize their own angry reactions, to address self-defeating, even suicidal thinking, and to avoid substance use triggers, challenging relationships, or other negative influences. Other reported strategies included seeking out knowledge about resources and HIV, submitting formal complaints about service providers who they deemed incompetent, and obtaining income by securing legitimate employment, turning “street skills” into more legitimate money-earning ventures, or engaging in criminal activity.

Although participants did not directly describe shifts from active substance use to sobriety as contributing to their HIV care engagement, they discussed how active use impeded care engagement. Furthermore, spirituality, faith, and Twelve Step philosophies were often evident in their positive coping strategies. Some participants expressed the importance of maintaining a positive outlook and gratitude for what they had rather than dwelling on the negatives or what they lacked. They also described purposefully addressing their HIV-related care in stages whenever the process of HIV care engagement felt overwhelming. However this meant that, some avoided doing things they could to ensure they were immediately and on consistently on antiretroviral treatment. For example, because of the many bureaucratic challenges involved, a number of participants described having to employ incredible levels of patience and persistence in order to (re)establish their benefits and obtain consistent care. Here, a participant describes how adopting a positive attitude throughout helped him:

“I can be on it [ARV medication] for a month. The next month, something comes up in regard to insurance, and I'm not on it. So basically, being a positive, objective person. I think that kind of helps with my not going into -- my viral load going up, T cells going down -- even though I've been having this problem with meds.” – Darnell, Group 1

Finally, participants discussed their strategies for dealing with HIV stigma – something they often did by avoiding disclosure, but also by disclosing their status in order to feel responsible to their sexual partners and comfortable with themselves. Again, we note that only female partners were directly referenced in the discussion of HIV disclosure to partners.

Participant resource knowledge

Participants differed widely in their awareness of and in their ability to access community resources. Knowledge of resources or personal connections to those who were knowledgeable, substantially eased the strain of HIV disease and engendered self-confidence:

“I'm very comfortable with it [HIV] now because now I know more about this and I know that I'm not the only one. There are individuals like these people here that I could probably go ask a question and they'd listen. Would you have the resources for it or an answer? If not, maybe they could direct me to something? … To me it means a lot.”– Rich, Group 4

Participants were typically eager to share what they knew, even with others in the discussion groups. The most knowledgeable participants tended to be those who were first diagnosed with HIV and had first received HIV services prior to entering prison. On release, these individuals frequently picked up with their HIV medical care where they had left off:

“Because I'm already like plugged in, so as soon as I come home, I call, okay, I got my medication. When's my next appointment? And they had it right up.”– John, Group 5

By contrast, those whose first interactions with the HIV care system occurred in custody and who had received little-to-no transitional linkage services described being lost and not fully able to take advantage of community resources.

Transitional linkage support

Transitional linkage support refers to services designed to help individuals with HIV care transition from prison into community-based services. Several participants reported the need for more transitional linkage support, and few reported receiving in-depth linkage support that began in custody. The comprehensiveness of the support received depended on their providers, the CDCR facility in which they had been housed and the services they sought out. However, even with extensive support, problems were sometimes encountered post release:

“At my institution, … they have just about every resource opportunity to set you up to get out. But there's no follow through on it. They signed me up to get MediCal when I got out, four months before I got out. I still [don't] have MediCal.”- Larry, Group 3

Obtaining one's prison medical records and identification card were aspects of linkage support that frequently worked smoothly and quickly. Because these documents suggest appropriate treatment regimens and signal eligibility for various services, they play a key role in ensuring access to optimal HIV treatment and other services post release. State prisoners who are on HIV antiretrovirals are also supposed to receive a 30-day supply of these medications on release. Most participants received this without incident and then obtained treatment in the community prior to the end of the 30 days. Those who experienced problems obtaining their release medications attributed this to logistical issues in the CDCR that caused delays, meaning that they were eligible for prison release prior to their medication being available to take with them.

Although not considered a transitional linkage support service, we note that a few participants indicated that the drug testing conducted as condition of their parole helped them remain to clean and sober and avoid activity that would lead to their re-incarceration. Such periods of sobriety can also be seen as facilitators to HIV care retention and treatment adherence because they allow clear thinking and attendance to self-care.

Adequate and stable housing

There was a strong consensus across all focus groups that stable, appropriate housing is a key factor to a successful transition into the community and engagement in HIV care. Here, Darnell summarizes most of the reasons mentioned for this, as well as characteristics of adequate housing – security, privacy, stability, cleanliness, and a minimum of hassles or distractions from other residents.

“Well, just that I know that having - living in a clean environment, stable, secure and having the virus that that type of situation wouldn't do it much good. To have peace of mind, I think it promotes peace of mind where you don't have to worry about, like you said, Alpha. Someone coming and all of a sudden says, ‘Hey, get out!’ Or waiting on a line of people to get into the bathroom. And probably the same way when you have to use the kitchen.… Those things I think make a big difference in your health, even if you didn't have the virus,… Besides getting on a regimen and having it as stable as possible, my only other goal is to have a place where that is permanent and a decent environment.”- Darnell, Group 1

Some participants were able to gain stable housing through sharing it with a relative or significant other, while others had to work with transitional case managers or community based agencies to obtain it. Several were still working to attain it.

Individual Attitudes

In addition to the relationships, resources, and strategies just discussed, a positive shift in attitudes and perceptions helped participants to prioritize and manage their HIV medical care.

Maturity

Participants described how incarceration and other life events had humbled them, shifted their perspective on life, and led them to apply themselves and their skills to living a different life upon reentry. They also described maturity as taking responsibility for one's actions, holding oneself accountable for one's situation, and addressing life challenges directly. This was seen when participants took the initiative to obtain their HIV medications and the initial steps to become connected to HIV medical care, as reflected in this comment: “… if you don't put in the effort, nothing's gonna change.”–Ferrell, Group 2

Being tired of recidivism

Participants described feeling tired of cycling in and out of prison, with half explicitly stated stating their fatigue with prison life and a preference for even a meager status with the general community. The stresses of incarceration were also described as wearing on one's physical and mental health. Furthermore, many discussed coming to the realization that incarceration had interfered with accomplishing goals and making positive contributions. Some of their comments, however, made clear how difficult it might be for them to forge a different path given their minimal prior preparation:

“Some people can change. But, for me, it's hard. You know what I mean? I've never worked -- all my life. So – I don't know how to work…. I mean I could probably learn, but …. I just need something, because I wanna get a job. Because I'm tired of going to prison.” -- Gerald, Group 6

Participants described losing interest in dealing drugs, running illegal businesses, and abusing substances. Several also expressed finally discovering patience with life and no longer desiring to live only in the moment and make fast money. These participants reported striving to live a in a manner that matched societal norms and included having a place of employment, a home, and a means of transportation. They noted that leading an illegal lifestyle was stressful. Below, Steve describes how the associated chaos and brief jail stints contributed to his non-adherence:

“It throws my regimen off because sometimes, I'll be so screwed up in the head by being there. It's like, did I take it? I can't remember really, did I take it or not. And sometimes, I'm over medicating myself because I'm thinking I didn't take it.” – Steve, Group 1

Adjustment to having HIV

Denial and depression were typical initial responses to participants' HIV diagnosis. For those who eventually adjusted, this process was often accompanied by obtaining HIV information and accepting both their own actions that contributed to HIV infection and others' potentially negative reactions to the disease. This adjustment process contributed to their adhering to antiretroviral medications and protecting partners from infection by allowing them to take responsibility and prioritize their own health over fears related to HIV stigma. In contrast, a few participants indicated that had they immediately accepted their diagnosis, attributing this to their typically calm dispositions or prior knowledge about HIV disease.

Participants also spoke of optimism about their health that emanated from acquiring knowledge about the virus and trusting in the efficacy of antiretroviral medications. Although few described the availability of HIV education in prison as adequate, several mentioned prison based classes/programs that had increase their HIV knowledge and helped them to unlearn false information that they had acquired from their social networks. In turn, this new information motivated them to maintain their antiretroviral regimens:

“I had learned a lot more about the virus. And decided to try the medications and at least give it a chance. And so I had just been on that rocky hill with medication…. I think also how to increase your life expectancy. Before I started to research myself, I was just hearing bits and pieces from the streets. And it was like what I was hearing was once you got it, you're going to die…. And so I think that people ought to try to understand that you can live many, many years.” -Darnell, Group 1

Discussion

This research highlights a wide range of factors that positively affects the level of engagement in HIV medical care of HIV-positive individuals who were recently incarcerated in a California State prison. While some of these – e.g., adequate housing, social support, positive patient/provider relationships, resource knowledge, and adjustment to HIV diagnosis have been shown previously to facilitate care in HIV positives who have not experienced incarceration (Kempf et al., 2010; Mallinson, Rajabiun, & Coleman, 2007; Messer et al., 2013; Pecoraro et al., 2013; Smith, Fisher, Cunningham, & Amico, 2012) –others are unique to those who have. These include transitional linkage support, factors related to successful re-entry (tired of recidivism, maturity, coping strategies), and the timing of HIV diagnosis/care relative to periods of incarceration. This emphasizes the importance of targeted services and service providers to help bridge HIV care for patients from prison settings to community settings. Even the influence of those facilitators not unique to re-entry populations seemed to be shaped by the participants' experiences of incarceration. For example social support received was often complicated by the distance, distrust and dependency created by histories of criminal justice involvement or was now unavailable for these reasons. This loss of social contacts may have heightened the level of importance that participants placed on the caring or lack of caring they perceived from their HIV medical providers. Individuals with high levels of social support are more likely to be retained in HIV care and treatment adherent (Halperin, Pathmanathan, & Richey, 2013; Kelly, Hartman, Graham, Kallen, & Giordano, 2014; Lehavot et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012). While our findings provide further support for the importance of social support, they also indicate the complexities encountered by both HIV-positive former prisoners and their loved ones in negotiating these relationships.

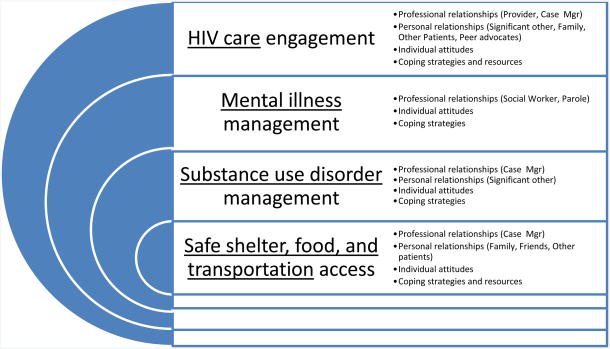

Springer et al. adapted Maslow's hierarchy of needs in order to describe HIV-positive reentry population's needs and priorities (Springer, Spaulding, Meyer, & Altice, 2011). Their model, which we have adapted and presented in Figure 2, emphasizes that HIV care is a need that cannot be adequately addressed until other key needs are met. At the most basic level, these needs include housing, shelter, and nutrition. For a large portion of the population, they next include addressing substance abuse and mental illness. In their review article, Springer et al. point to case management, treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders, and adherence interventions for meeting these needs. Our focus group discussions included individuals who had not been always able to access treatments for either type of disorder, but who nevertheless drew on other types of resources to help manage these disorders, meet their basic needs, and navigate complicated HIV care and social service systems. Along with supporting the basic premise of Springer's model, our focus on facilitators of successful care engagement in this population highlights specific personal, interpersonal, and informational factors that increase the likelihood that HIV-positive former prisoners will be able to meet (or at least manage) their more primary needs. These factors, in turn, may increase former prisoners' ability and motivation to address their need for consistent HIV medical care.

Figure 2.

Adaptation of Springer et al 2011 representation of Maslow's hierarchy of needs as it applies to incarcerated HIV-infected patients and identified facilitators to addressing the needs underlined (Springer et al., 2011).

Our findings are largely consistent with Springer et al.'s adaptation of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs to post-incarcerated HIV-positive persons (Springer et al., 2011). They identify, however, potentially important missing components by elucidating the roles of social support and information provision via informal and formal peer support channels in helping to shape participants' interactions, attitudes and expectations regarding services and service providers. The role of informal sources of information may be particularly important to this group whose access to and ability to comprehend written sources of information may be low and who may view official sources of information with particular suspicion because of its marginalized status and prior negative interactions with government and health-related institutions. This points to several points of intervention, including strategies to improve provider-patient communication and increase provider trust, educational efforts that include the social networks of those who are post incarcerated, and peer-based interventions that train and connect HIV+ individuals who have experienced incarceration and achieved success in managing life and HIV disease in the community with similar individuals who have been recently released.

We also note that recidivism was a major issue. Many participants had experienced multiple incarcerations, and staying out of prison was a major discussion point across groups. One study of HIV-positive jail releases found that one-third re-incarcerated within six months, with higher recidivism rates seen among those with prior homeless, psychiatric disorders, or lack of health insurance in the 30 days post release (Fu et al., 2013). Fortunately, changes that support HIV care engagement may also help prevent recidivism—including reducing substance use, reducing the likelihood that individuals resort to criminal activities in order to address their basic needs, and increasing their reliance on positive coping strategies through the assistance of case managers, peer advocates, and other providers (Jacob Arriola, Braithwaite, Holmes, & Fortenberry, 2007; Listwan, Cullen, & Latessa, 2006; Visher & Courtney, 2007).

Our Introduction noted the sparse research on this topic in California (CA) and the transcripts do reveal impacts of some CA-specific features and policies. CA has a large network of Ryan White providers who are able to care for individuals who lack a means of payment and has had a well-funded AIDS Drug Assistance Program throughout the epidemic. So, individuals rarely indicated they could not locate a provider or were unable to obtain a prescription in the community. CA prisons routinely release HIV-positive prisoners, who are on treatment, with a 30-day supply of their HIV medications, further reducing the likelihood of treatment gaps. For many years, most HIV-positive prisoners were housed in just a couple of state facilities, in order for the system to best manage their medical care. Although HIV-patients are now more dispersed in the prisons, these facilities continue to have the highest number HIV services (including transitional case management), as was participants noted. Affecting prisoners post-release, however, are CA's fairly restrictive policies regarding the rights of those convicted of various crimes. Those convicted of certain drug-related felonies are not eligible for food stamps, and food stamps can be denied those found to be violating their parole or probation restrictions. Public housing assistance is denied to many based on their convictions, and severe residential restrictions are placed on registered sex offenders (Prison Law Office 2011). Together with the very high housing costs in CA, these policies likely heightened the challenges participants faced in securing appropriate, stable long-term housing. The relatively rich HIV service environment may explain the fact that over 80% of our participants received HIV antiretrovirals within 30 days of their release; while the high poverty and cost of living rates may explain why other instrumental supports received were so important to their ongoing care engagement.

These data have a number of limitations. They come from a small, selective sample of HIV-positive former prisoners from Los Angeles. Although, Los Angeles County is of particular importance because over one-third of all California state prisoners return to the County (Davis et al., 2009), Black men are overrepresented in our sample and women and men of other race/ethnicities are underrepresented. Women and men of other backgrounds may experience other barriers to care or be best supported by different facilitators than those identified here. Some of women's barriers to care may be related to reasons identified in the literature for a lower tendency of women than men to participate in health research, including reduced mobility and greater caretaking responsibilities (Infanti et al., 2014; Rivers, August, Sehovic, Lee Green, & Quinn, 2013; Sharp et al., 2006). Two of our groups included only two participants, too small for generating much of the type of interaction desired from a focus group format. The fact that our predominately male participants described support from female but not male significant others, warrants further study. It may reflect silencing due the nature of focus group discussion, which can encourage silence around sensitive topics and to perceived homophobia within the focus group members. Nevertheless, it may also reflect former prisoners' challenges with forming and maintaining supportive same-sex partnerships. Despite these limitations, the findings add to the literature by expanding on the types of needs that, when met, facilitate care engagement for post-incarcerated individuals during reentry and by revealing how it is that specific factors facilitate the care engagement process.

A broad range of factors can and do support HIV care engagement for HIV-positive former prisoners. Several of these could be promoted through interventions that build on peer navigation approaches, provide targeted HIV education, address substance use disorders, and work to secure stable, appropriate housing. HIV medical provider-based interventions may also be helpful if they can encourage the type of provider communication and sensitivity that resonate with rather than alienate patients who are former prisoners. Finally, efforts to engage and enhance potentially positive interpersonal relationships, by educating and supporting the familial and social network members of former prisoners, have the potential to yield sustained and far-reaching effects. These are the individuals who take patients to their appointments, advise them while waiting to see their own providers, offer them income-earning opportunities, and provide them a place to stay or send their mail on release. Their points of interaction and connection with patients extend well beyond that of the medical and social service settings and providers that are the frequent points of intervention. Similarly, parole and probation officers play a major role in the lives of former prisoners during reentry to society. However, based both on our review of the literature and the focus group discussions, they are not currently playing any direct role in helping to move HIV-positive former prisoners along the HIV care continuum. Shifting this dynamic would require careful attention to ethical issues of confidentiality and potential coercion, but warrants consideration and research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gil Montgomery, our community advisory board members, and the study participants.

This research was supported by NIH/NCRR/NCATS UCLA CTSI UL1TR000124. Additional support for Dr. Harawa and Mr. McCuller comes from the California HIV/AIDS Research Program RP11-LA-020 and NIMH P30 MH58107.

Contributor Information

Natalie Bracken, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science.

Charles Hilliard, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science.

William J. McCuller, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science.

Nina T. Harawa, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science and University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine.

References

- Baillargeon JG, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Rich JD, Paar DP. Enrollment in outpatient care among newly released prison inmates with HIV infection. Public Health Reports. 2010;125 Suppl 1:64–71. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon JG, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, Paar DP. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301(8):848–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon JG, Paar DP, Wu H, Giordano TP, Murray O, Raimer BG, et al. Pulvino JS. Psychiatric disorders, HIV infection and HIV/hepatitis co-infection in the correctional setting. AIDS Care. 2008;20(1):124–129. doi: 10.1080/09540120701426532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Perry N, Safren SA. Mental health: a focus on stress, coping, and mental illness as it relates to treatment retention, adherence, and other health outcomes. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):215–222. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0089-1. doi:210.1007/s11904-11011-10089-11901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., & Prevention. Routine HIV screening during intake medical evaluation at a County Jail - Fulton County, Georgia, 2011-2012. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(24):495–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LM, Nicosia N, Overton A, Miyashiro L, Derose KP, Fain T, et al. Williams E. Health and Infrastructure, Safety and Environment. RAND Corporation; 2009. Understanding the Public Health Implications of Prisoner Reetry in California. Phase I Report. [Google Scholar]

- Evans T, Tinsley AM. Texas has nation's largest prison population. The Fort worth Star-Telegram 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Beckerman A. Recently released with HIV/AIDS: primary care treatment needs and experiences. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18(3):699–714. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Andersen MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, Starrels JL, Cunningham CO. Health outcomes and retentions in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration Transitions Clinic. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2014;25.3(3):1139–1159. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JJ, Herme M, Wickersham JA, Zelenev A, Althoff A, Zaller ND, et al. Altice FL. Understanding the revolving door: individual and structural-level predictors of recidivism among individuals with HIV leaving jail. AIDS Behav. 2013;17 Suppl 2:S145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0590-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Barinas J, O'Cleirigh C. Substance use: impact on adherence and HIV medical treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):223–234. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DF, Golin CE, Farel CE, Wohl DA, Scheyett AM, Garrett JJ, et al. Parker SD. Multilevel challenges to engagement in HIV care after prison release: a theory-informed qualitative study comparing prisoners' perspectives before and after community reentry. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin J, Pathmanathan I, Richey LE. Disclosure of HIV status to social networks is strongly associated with increased retention among an urban cohort in New Orleans. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2013;27(7):375–377. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzke AJ, Ross MW, Scott DP. Predictors of post-release primary care utilization among HIV-positive prison inmates: a pilot study. AIDS Care. 2006;18(4):290–301. doi: 10.1080/09540120500161892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Thompson BJ, Nutt Williams E. A Guide to Conducting Consensual Qualitative Research. The Counseling Psychologist. 1997;25(4):517–572. [Google Scholar]

- Infanti JJ, O'Dea A, Gibson I, McGuire BE, Newell J, Glynn LG, et al. Dunne FP. Reasons for participation and non-participation in a diabetes prevention trial among women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;1413 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Arriola KR, Braithwaite RL, Holmes E, Fortenberry RM. Post-release case management services and health-seeking behavior among HIV-infected ex-offenders. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18(3):665–674. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JD, Hartman C, Graham J, Kallen MA, Giordano TP. Social Support as a Predictor of Early Diagnosis, Linkage, Retention, and Adherence to HIV Care: Results From The Steps Study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf MC, McLeod J, Boehme AK, Walcott MW, Wright L, Seal P, et al. Moneyham L. A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators to retention-in-care among HIV-positive women in the rural southeastern United States: implications for targeted interventions. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2010;24(8):515–520. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Encinosa W. Effects of antidepressant treatment on antiretroviral regimen adherence among depressed HIV-infected patients. Psychiatr Q. 2009;80(3):131–141. doi: 10.1007/s11126-009-9100-z. doi:110.1007/s11126-11009-19100-z. Epub 12009 Apr 11122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Huh D, Walters KL, King KM, Andrasik MP, Simoni JM. Buffering effects of general and medication-specific social support on the association between substance use and HIV medication adherence. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2011;25(3):181–189. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines R. Using human rights law to advocate for syringe exchange programs in European prisons. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2006;11(2-3):80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listwan SJ, Cullen FT, Latessa EJ. How to prevent prisoner re-entry programs from failing: Insights from evidence-based corrections. Federal Probation. 2006;70(3) [Google Scholar]

- MacGowan RJ, Margolis A, Gaiter J, Morrow K, Zack B, Askew J, et al. Project SSG. Predictors of risky sex of young men after release from prison. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2003;14(8):519–523. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson RK, Rajabiun S, Coleman S. The provider role in client engagement in HIV care. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S77–84. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez DA, Goggin K, Catley D, Gerkovich MM, Williams K, Wright J, et al. Motiv Do coping styles mediate the relationship between substance use and educational attainment and antiretroviral adherence? AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2319–2329. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Quinlivan EB, Parnell H, Roytburd K, Adimora AA, Bowditch N, DeSousa N. Barriers and facilitators to testing, treatment entry, and engagement in care by HIV-positive women of color. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2013;27(7):398–407. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Cornwall A, Fu J, Bazerman L, Loewenthal H, Beckwith C. Linking HIV-positive jail inmates to treatment, care, and social services after release: results from a qualitative assessment of the COMPASS Program. Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87(6):954–968. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9496-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Chan K, Wood E, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy and continuity of HIV care: the impact of incarceration and prison release on adherence and HIV treatment outcomes. Antivir Ther. 2004;9(5):713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro A, Royer-Malvestuto C, Rosenwasser B, Moore K, Howell A, Ma M, Woody GE. Factors contributing to dropping out from and returning to HIV treatment in an inner city primary care HIV clinic in the United States. AIDS Care. 2013;25(11):1399–1406. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.772273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prison Law Office. [Accessed July 11, 2015];Benefits Available to Paroling and Discharging Inmates. 2011 Aug; www.prisonlaw.com.

- Rivers D, August EM, Sehovic I, Lee Green B, Quinn GP. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans' participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):13–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MI, Black AC, Arnsten JH, Goggin K, Remien RH, Simoni JM, et al. Liu H. Association between use of specific drugs and antiretroviral adherence: findings from MACH 14. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp L, Cotton SC, Alexander L, Williams E, Gray NM, Reid JM, Group T. Reasons for participation and non-participation in a randomized controlled trial: postal questionnaire surveys of women eligible for TOMBOLA (Trial Of Management of Borderline and Other Low-Grade Abnormal smears) Clin Trials. 2006;3(5):431–442. doi: 10.1177/1740774506070812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LR, Fisher JD, Cunningham CO, Amico KR. Understanding the behavioral determinants of retention in HIV care: a qualitative evaluation of a situated information, motivation, behavioral skills model of care initiation and maintenance. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2012;26(6):344–355. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: five essential components. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53(5):469–479. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, McKaig R, Golin CE, Shain L, Adamian M, et al. Kaplan AH. Sexual behaviours of HIV-seropositive men and women following release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(2):103–108. doi: 10.1258/095646206775455775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visher CA, Courtney SME. Returning Home Policy Brief: One Year Out Expereinces of Prisoners Returning to Cleveland. The Urban Institute; Washington D.C: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CE, White B, Matuszewski J, Bowling M, et al. Earp J. Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2011a;15(2):356–364. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]