To the Editor

Physicians often delay hospice discussions with their terminally-ill patients despite guidelines recommending such discussions for patients expected to die within one year,1,2 but reasons for this are not well understood. Evidence suggests that physicians “practice what they preach” when counseling about health behaviors3 although their treatment recommendations may not necessarily reflect their own preferences, with one study suggesting they recommend more conservative treatments than they might choose for themselves.4 As physicians may prefer less aggressive end-of-life care than their patients generally receive,5 physicians’ personal preferences for hospice may influence their approach to hospice discussions with their terminally-ill patients.

We examined physicians’ reported preferences for hospice enrollment if they were terminally ill. We also assessed whether physicians who would enroll in hospice if terminally ill differed from others in the timing of hospice discussions with their patients.

Methods

We surveyed physicians caring for cancer patients enrolled in the multiregional population-based Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study.1 Physicians indicated on a 5-point Likert scale how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the statement “If I were terminally ill with cancer, I would enroll in hospice.” They were also asked to assume they were caring for an asymptomatic advanced-cancer patient who they believed had 4–6 months to live and report whether they would discuss hospice with the patient: “now”, “when the patient first develops symptoms”, “when there are no more non-palliative treatments to offer”, “only if the patient is admitted to the hospital”, or “only if the patient and/or family bring it up.”1

Among 4388 respondents (response rate 61%), we excluded 105 who did not answer the hospice self-preference question and 15 who graduated after 2004. Multiple imputation was used to address item non-response in the adjusted analyses.6

We used multivariable logistic regression to examine physician and practice factors associated with physicians’ strong agreement that they would enroll in hospice if terminally ill with cancer. In a second model, we assessed if physicians who strongly agreed they would enroll in hospice were more likely than other physicians to report discussing hospice “now” with their terminally-ill patients. We omitted variables with adjusted P>0.10.

Results

Respondents’ characteristics are shown in the Table. Most strongly (64.5%) or somewhat (21.4%) agreed that they would enroll in hospice if terminally ill. In adjusted analyses, physicians who were female, cared for more terminally-ill patients, and worked in managed-care settings were more likely than others to strongly agree they would enroll in hospice. Surgeons and radiation oncologists were less likely than primary care physicians to strongly agree they would enroll in hospice.

Table.

Physician Willingness to Enroll in Hospice: Personal and Practice Characteristicsa

| Physician Characteristics | Total N (%) | Unadjusted Proportion Who Strongly Agree they would Enroll in Hospice if Terminally Ill with Cancer (%) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) of Strongly Agreeing they would Enroll in Hospiceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4,368 (100) | 64.5 | |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 39 | 959 (22) | 65.4 | 1.00 |

| 40 – 49 | 1264 (29) | 65.5 | 1.08 (0.89, 1.31) |

| 50 – 54 | 767 (18) | 67.1 | 1.18 (0.95, 1.47) |

| 55 – 59 | 702 (16) | 65.4 | 1.20 (0.96, 1.50) |

| ≥ 60 | 676 (15) | 57.7 | 1.00 (0.79, 1.25) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3453 (80) | 61.9 | 1.00 |

| Female | 837 (20) | 76.1 | 1.80 (1.49, 2.18) |

| Specialty | |||

| Primary Care Physician | 1743 (41) | 69.5 | 1.00 |

| Surgery | 923 (22) | 56.6 | 0.65 (0.55, 0.78) |

| Medical oncology | 600 (14) | 70.3 | 0.93 (0.74, 1.17) |

| Radiation oncology | 257 (6) | 57.6 | 0.57 (0.42, 0.76) |

| Other specialty | 768 (18) | 61.2 | 0.75 (0.62, 0.90) |

| Percent of Patients in Managed Care | |||

| ≤ 50% | 2330 (58) | 60.8 | 1.00 |

| ≥ 51% | 1664 (42) | 69.8 | 1.30 (1.12, 1.51) |

| Number of Terminally-Ill Patients in the Last Year | |||

| ≤ 12 | 2308 (54) | 62.5 | 1.00 |

| ≥ 13 | 1998 (46) | 67.1 | 1.29 (1.12, 1.50) |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; CI, confidence interval.

Percentages include only reported, non-imputed values and may not sum to 100% due to rounding or missing values. Missing values were present for the following variables: sex (N=78), specialty (N=77), proportion of patients in managed care (N=374), and number of terminally-ill patients cared for in the past year (N=62). Adjusted analyses used imputed data.

Adjusting for all variables in the table, as well as type of practice. Board certification, US medical school graduate status, and level of teaching involvement were not associated in unadjusted analyses and were not included in the model

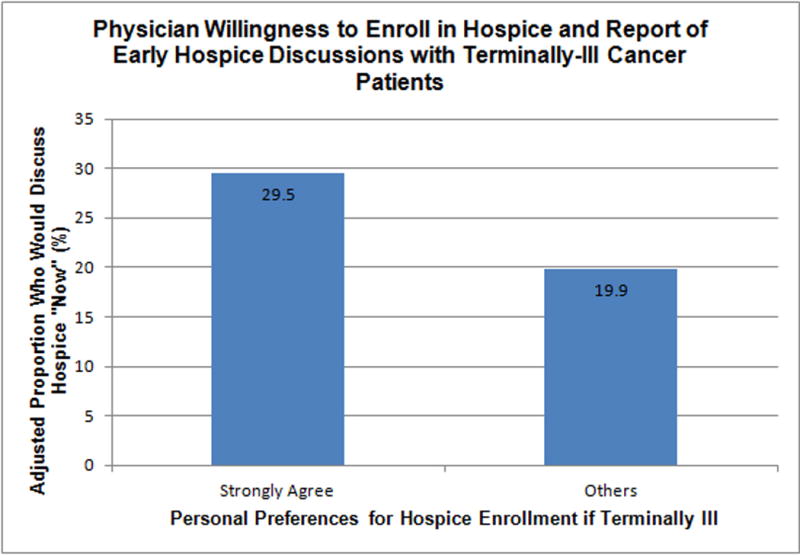

Overall, 26.5% reported they would discuss hospice “now” with a patient who had 4–6 months to live. Other physicians reported they would wait until the patient has symptoms (16.4%) or there were no more treatments to offer (48.7%) or would discuss hospice only if the patient and/or family brings it up (4.3%) or the patient is hospitalized (4.1%). After adjustment, physicians who strongly agreed they would enroll in hospice themselves were more likely than other physicians to report discussing hospice “now” (OR=1.7, 95% CI=1.5–2.0) (Figure).

Figure.

Comment

Most physicians reported they would enroll in hospice if they were terminally ill with cancer, particularly women, primary care physicians, and those in managed-care settings and with more terminally-ill patients. Physicians with strong personal preferences for hospice were more likely than others to report discussing hospice with their patients earlier. Physicians should consider their personal preferences for hospice as a factor as they care for terminally-ill cancer patients. Physicians with negative views of hospice may benefit from additional education about how hospice may help their patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the Statistical Coordinating Center (U01 CA093344) and the NCI-supported Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (Dana Farber Cancer Institute/Cancer Research Network U01 CA093332, Harvard Medical School/Northern California Cancer Center U01 CA093324, RAND/UCLA U01 CA093348, University of Alabama at Birmingham U01 CA093329, University of Iowa U01 CA093339, University of North Carolina U01 CA093326) and by a Department of Veterans Affairs grant to the Durham VA Medical Center CRS 02-164. Dr. Keating’s effort was also funded by 1R01CA164021-01A1.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors of the study had no role in the design and conduct of this study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Liu and Keating had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Chinn, Liu, and Keating. Acquisition of data: Liu and Keating. Analysis and Interpretation of the Data: Chinn, Liu, Klabunde, Kahn, and Keating. Drafting of the manuscript: Chinn, Liu, and Keating. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Chinn, Liu, Klabunde, Kahn, and Keating. Statistical analysis: Liu. Study Supervision: Keating.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Previous Presentation: Portions of this work was presented in abstract form at the Society of General Internal Medicine’s 36th Annual Meeting; April 25, 2013; Denver, Colorado.

Additional Contributions: The authors would like to thank Robert Fletcher, MD, MSc, Professor Emeritus, Harvard Medical School, for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Garrett M. Chinn, Email: chinn.garrett@mgh.harvard.edu, Division of General Medicine, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Pang-Hsiang Liu, Email: phliu@hcp.med.harvard.edu, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Carrie N. Klabunde, Email: klabundc@mail.nih.gov, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

Katherine L. Kahn, Email: kkahn@mednet.ucla.edu, RAND, Santa Monica, California and Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California.

Nancy L. Keating, Email: keating@hcp.med.harvard.edu, Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end of life care. Cancer. 2010;116(4):998–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Palliative Care. version 1.2013. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wells KB, Lewis CE, Leake B, Ware JE. Do physicians preach what they practice? A study of physicians’ health habits and counseling practices. JAMA. 1984;252(20):2846–2848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ubel PA, Angott AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Physicians recommend different treatments for patients than they would choose for themselves. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):630–634. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramelspacher GP, Zhou X-H, Hanna MP, Tierney WM. Preferences of physicians and their patients for end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):346–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Landrum MB, et al. Multiple imputation in a large-scale complex survey: a practical guide. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010;19(6):653–70. doi: 10.1177/0962280208101273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]