A wide range of patients may be considered for percutaneous coronary intervention. It is essential that the benefits and risks of the procedure, as well as coronary artery bypass graft surgery and medical treatment, are discussed with patients (and their families) in detail. They must understand that, although the percutaneous procedure is more attractive than bypass surgery, it has important limitations, including the likelihood of restenosis and potential for incomplete revascularisation compared with surgery. The potential benefits of antianginal drug treatment and the need for risk factor reduction should also be carefully explained.

Clinical risk assessment

Relief of anginal symptoms is the principal clinical indication for percutaneous intervention, but we do not know whether the procedure has the same prognostic benefit as bypass surgery. Angiographic features determined during initial assessment require careful evaluation to determine the likely success of the procedure and the risk of serious complications.

Until recently, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association classified anginal lesions into types (and subtypes) A, B, or C based on the severity of lesion characteristics. Because of the ability of stents to overcome many of the complications of percutaneous intervention, this classification has now been superseded by one reflecting low, moderate, and high risk.

Successful percutaneous intervention depends on adequate visualisation of the target stenosis and its adjacent arterial branches. Vessels beyond the stenosis may also be important because of the potential for collateral flow and myocardial support if the target vessel were to occlude abruptly. Factors that adversely affect outcome include increasing age, comorbid disease, unstable angina, pre-existing heart or renal failure, previous myocardial infarction, diabetes, a large area of myocardium at risk, degree of collaterisation, and multivessel disease.

Preparation for intervention

Patients must be fully informed of the purpose of the procedure as well as its risks and limitations before they are asked for their consent. The procedure must always be carried out (or directly supervised) by experienced, high volume operators (> 75 procedures a year) and institutions (> 400 a year).

Table 1.

New classification system of stenotic lesions (American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association)

| Low risk | Moderate risk | High risk |

|---|---|---|

| Discrete (<10 mm) | Tubular (10-20 mm) | Diffuse (>20 mm) |

| Concentric | Eccentric | |

| Readily accessible | Proximal segment moderately tortuous | Proximal segment excessively tortuous |

| Segment not angular (<45°) | Segment moderately angular (45°-<90°) | Segment extremely angular (≥90°) |

| Smooth contour | Irregular contour | |

| Little or no calcification | Moderate or heavy calcification | |

| Occlusion not total | Total occlusion <3 months old | Total occlusion >3 months or bridging collateral vessels |

| Non-ostial | Ostial | |

| No major side branch affected | Bifurcated lesions requiring double guidewires | Inability to protect major side branches |

| No thrombus | Some thrombus | Degenerated vein grafts with friable lesions. |

A sedative is often given before the procedure, as well as aspirin, clopidogrel, and the patient's usual antianginal drugs. In very high risk cases an intra-aortic balloon pump may be used. A prophylactic temporary transvenous pacemaker wire may be inserted in some patients with pre-existing, high grade conduction abnormality or those at high risk of developing it.

Table 2.

Clinical indications for percutaneous coronary intervention

| • Stable angina (and positive stress test) |

| • Unstable angina |

| • Acute myocardial infarction |

| • After myocardial infarction |

| • After coronary artery bypass surgery (percutaneous intervention to native vessels, arterial or venous conduits) |

| • High risk bypass surgery |

| • Elderly patient |

The procedure

For an uncomplicated, single lesion, a percutaneous procedure may take as little as 30 minutes. However, the duration of the procedure and radiation exposure will vary according to the number and complexity of the treated stenoses and vessels.

Figure 1.

Percutaneous coronary intervention in progress. Above the patient's chest is the x ray imaging camera. Fluoroscopic images, electrocardiogram, and haemodynamic data are viewed at eye level screens. All catheterisation laboratory operators wear lead protection covering body, thyroid, and eyes, and there is lead shielding between the primary operator and patient

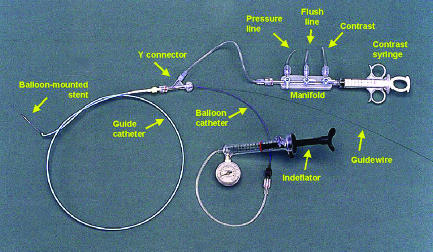

As with coronary angiography, arterial access (usually femoral but also brachial or radial) under local anaesthesia is required. A guide catheter is introduced and gently engaged at the origin of the coronary artery. The proximal end of the catheter is attached to a Y connector. One arm of this connector allows continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure. Dampening or “ventricularisation” of this arterial tracing may indicate reduced coronary flow because of over-engagement of the guide catheter, catheter tip spasm, or a previously unrecognised ostial lesion. The other arm has an adjustable seal, through which the operator can introduce the guidewire and balloon or stent catheter once the patient has been given heparin as an anticoagulant. A glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, which substantially reduces ischaemic events during percutaneous coronary intervention, may also be given.

Figure 2.

Equipment commonly used in percutaneous coronary interventions

Visualised by means of fluoroscopy and intracoronary injections of contrast medium, a soft tipped, steerable guidewire (usually 0.014″ (0.36 mm) diameter) is passed down the coronary artery, across the stenosis, and into a distal branch. A balloon or stent catheter is then passed over the guidewire and positioned at the stenosis. The stenosis may then be stented directly or dilated before stenting. Additional balloon dilatation may be necessary after deployment of a stent to ensure its full expansion.

Balloon inflation inevitably stops coronary blood flow, which may induce angina. Patients usually tolerate this quite well, especially if they have been warned beforehand. If it becomes severe or prolonged, however, an intravenous opiate may be given. Ischaemic electrocardiographic changes are often seen at this time, although they are usually transient and return to baseline once the balloon is deflated (usually after 30-60 seconds). During the procedure, it is important to talk to the patient (who may be understandably apprehensive) to let him or her know what is happening, as this encourages a good rapport and cooperation.

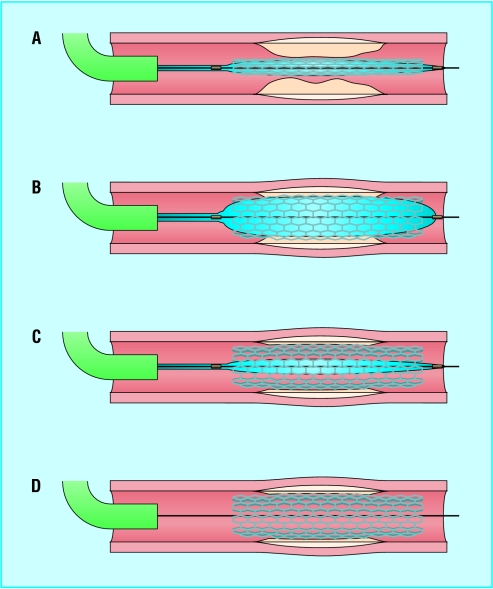

Figure 3.

Deployment of a balloon-mounted stent across stenotic lesion. Once the guide catheter is satisfactorily engaged, the lesion is crossed with a guidewire and the balloon-mounted stent positioned to cover the lesion (A). It may be necessary to pre-dilate a severe lesion with a balloon to provide adequate passageway for the balloon and stent. The balloon is inflated to expand the stent (B). The balloon is then deflated (C) and withdrawn leaving the guidewire (D), which is also removed once the operator is satisfied that a good result has been obtained

Recovery

After the procedure the patient is transferred to a ward where close monitoring for signs of ischaemia and haemodynamic instability is available. If a femoral arterial sheath was used, it may be removed when the heparin effect has declined to an acceptable level (according to unit protocols). Arterial sealing devices have some advantages over manual compression: they permit immediate sheath removal and haemostasis, are more comfortable for patients, and allow early mobilisation and discharge. However, they are not widely used as they add considerably to the cost of the procedure.

After a few hours, the patient should be encouraged to gradually increase mobility, and in uncomplicated cases discharge is scheduled for the same or the next day. Before discharge, the arterial access site should be examined and the patient advised to seek immediate medical advice if bleeding or chest pain (particularly at rest) occurs. Outpatient follow up and drug regimens are provided, as well as advice on modification of risk factors and lifestyle.

Complications and sequelae

Complications are substantially lower in centres where large numbers of procedures are carried out by adequately trained and experienced operators. Major complications are uncommon and include death (0.2% but higher in high risk cases), acute myocardial infarction (1%) which may require emergency coronary artery bypass surgery, embolic stroke (0.5%), cardiac tamponade (0.5%), and systemic bleeding (0.5%).

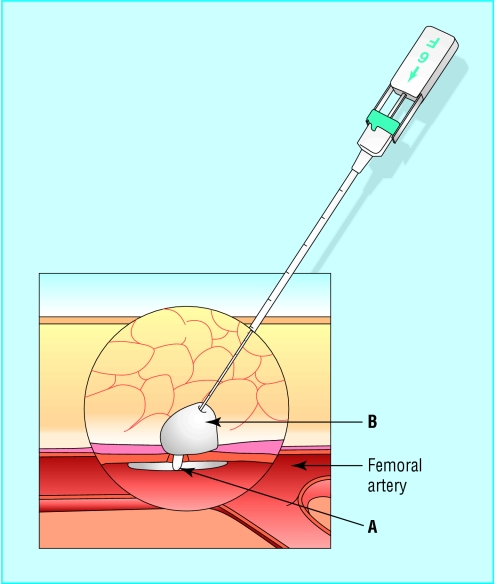

Figure 4.

Example of a femoral artery closure device. The Angio-Seal device creates a mechanical seal by sandwiching the arteriotomy between an anchor placed against the inner arterial wall (A) and collagen sponge (B), which both dissolve within 60-90 days

Minor complications are more common and include allergy to the contrast medium and nephropathy and complications of the access site (bleeding, haematoma, and pseudoaneurysm).

Restenosis within a stent

Although stents prevent restenosis from vascular recoil and remodelling, restenosis within the stent (known as “in-stent restenosis”) due to neointimal proliferation does occur and is the most important late sequel of the procedure. In-stent restenosis is the Achilles' heel of percutaneous revascularisation and develops within six months of stenting.

Figure 5.

The cutting balloon catheter. The longitudinal cutting blades are exposed only during balloon inflation (top left). In this case (top right) a severe ostial in-stent restenosis in the right coronary artery (arrow) was dilated with a short cutting balloon (bottom left), and a good angiographic result was obtained (arrow, bottom right)

Angiographic restenosis rates (> 50% diameter stenosis) depend on several factors and are higher in smaller vessels, long and complex stenoses, and where there are coexisting conditions such as diabetes. Approximate rates of angiographic restenosis after percutaneous angioplasty are

Angioplasty to de novo lesion in native artery—35%

Angioplasty and stent to de novo lesion in native artery—25%

Angioplasty and stent to restenotic lesion in native artery—20%

Angioplasty and stent to successfully recanalised chronic total occlusion—30%

Angioplasty to de novo lesion in vein graft—60%

Angioplasty and stent to de novo lesion in vein graft—30%.

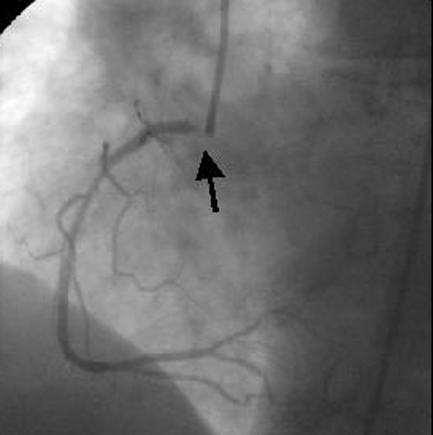

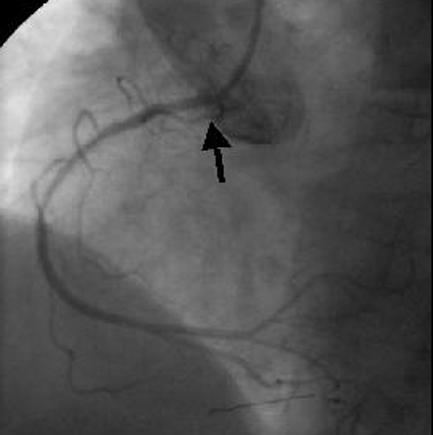

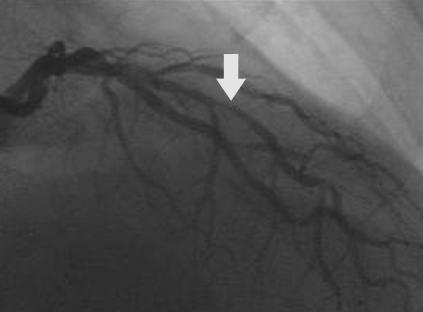

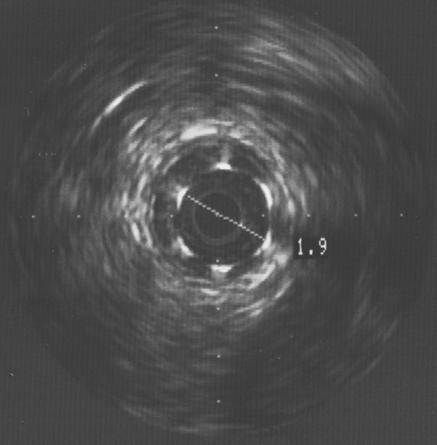

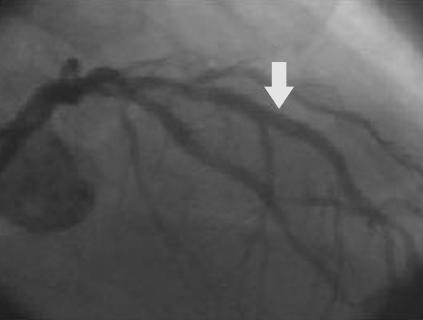

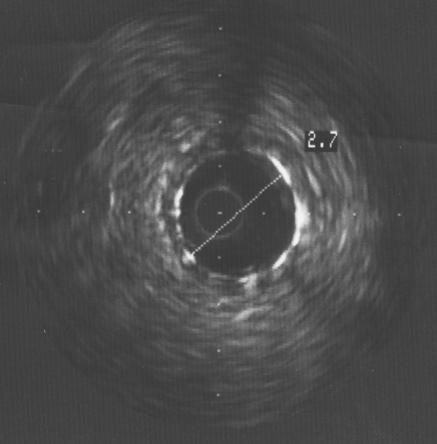

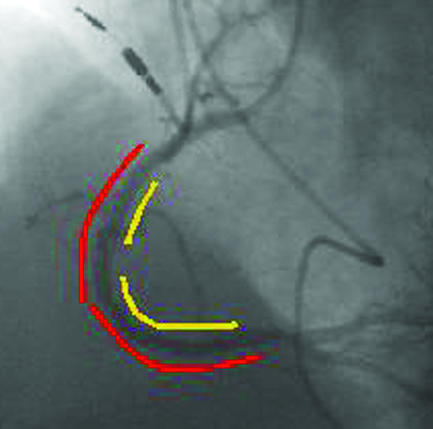

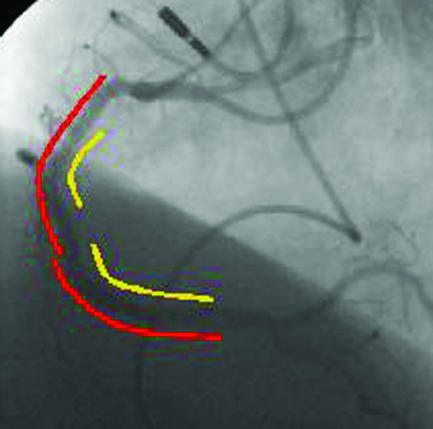

Figure 9.

Focal in-stent restenosis. A 2.0 mm stent had been deployed six months earlier. After recurrence of angina, angiography showed focal in-stent restenosis (arrow, top left). This was confirmed with intravascular ultrasound (top right), which also revealed that the stent was underexpanded. The stent was further expanded with a balloon catheter, with a good angiographic result (arrow, bottom left) and an increased lumen diameter to 2.7 mm (bottom right)

It should be noted that angiographically apparent restenoses do not always lead to recurrent angina (clinical restenosis). In some patients only mild anginal symptoms recur, and these may be well controlled with antianginal drugs, thereby avoiding the need for further intervention.

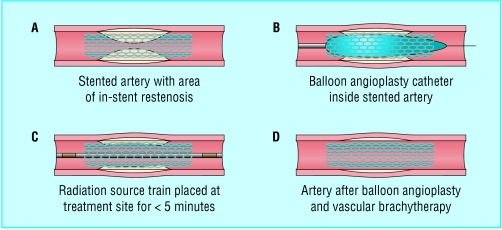

Figure 13.

Diagrammatic representation of the Novoste Beta Cath system used for vascular brachytherapy. Pre-dilatation of the in-stent restenosis with a balloon catheter is usual and is followed by positioning of the radiation source train, containing strontium-90, at the site for less than 5 minutes

Using repeat percutaneous angioplasty alone to re-dilate in-stent restenosis results in a high recurrence of restenosis (60%). Various other methods, such as removing restenotic tissue by means of atherectomy or a laser device or re-dilating with a cutting balloon, are being evaluated. Another method is brachytherapy, which uses a special intracoronary catheter to deliver a source of β or γ radiation. It significantly reduces further in-stent restenosis, but it has limitations, including late thrombosis and new restenosis at the edges of the radiation treated segments, giving rise to a “candy wrapper” appearance.

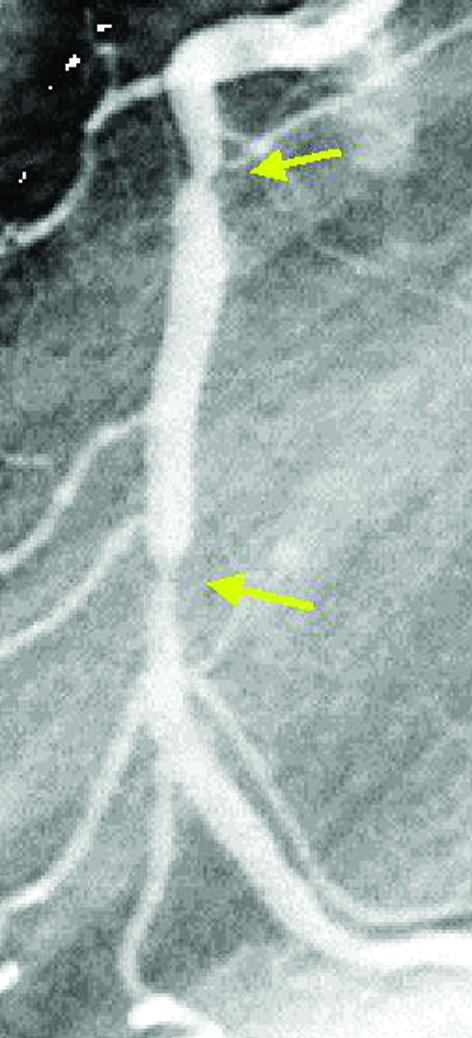

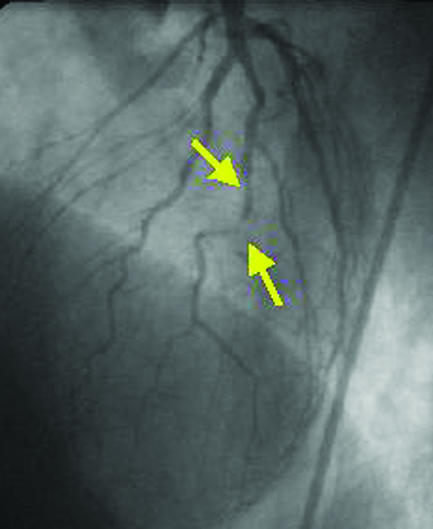

Figure 14.

Angiogram showing late “candy wrapper” edge effect (arrows) because of new restenosis at the edges of a segment treated by brachytherapy

Drug eluting, coated stents

Coated stents contain drugs that inhibit new tissue growth within the sub-intima and are a promising new option for preventing or treating in-stent restenosis. Sirolimus (an immunosuppressant used to prevent renal rejection which inhibits smooth muscle proliferation and reduces intimal thickening after vascular injury), paclitaxel (the active component of the anticancer drug taxol), everolimus, ABT-578, and tacrolimus are all being studied, as are other agents. Although long term data and cost benefit analyses are not yet available, it seems probable that coated stents will be commonly used in the near future.

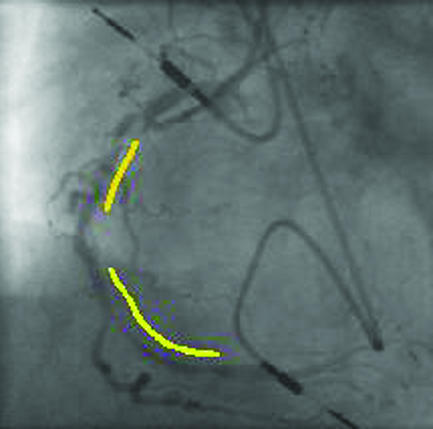

Figure 15.

Top left: four months after two stents (yellow lines) were deployed in the proximal and middle right coronary artery, severe diffuse in-stent restenosis has occurred with recurrent angina. Top right: two sirolimus coated Cypher stents (red lines) were deployed within the original stents. Bottom: after six months there was no recurrence of restenosis, and the 51 year old patient remained asymptomatic

Occupation and driving

Doctors may be asked to advise on whether a patient is “fit for work” or “recovered from an event” after percutaneous coronary intervention. “Fitness” depends on clinical factors (level of symptoms, extent and severity of coronary disease, left ventricular function, stress test result) and the nature of the occupation, as well as statutory and non-statutory fitness requirements. Advisory medical standards are in place for certain occupations, such as in the armed forces and police, railwaymen, and professional divers. Statutory requirements cover the road, marine, and aviation industries and some recreational pursuits such as driving and flying.

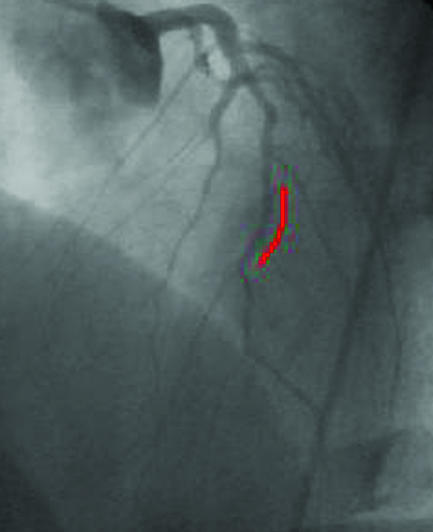

Figure 18.

The incidence of restenosis is particularly high with percutaneous revascularisation of small vessels. A small diseased diagonal artery (arrows, top left) in a 58 year old patient with limiting angina was stented with a sirolimus coated Cypher stent (red line, top right). After six months, no restenosis was present (left), and the patient remained asymptomatic

Patients often ask when they may resume driving after percutaneous coronary intervention. In Britain, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency recommends that group 1 (private motor car) licence holders should stop driving when anginal symptoms occur at rest or at the wheel. After percutaneous coronary intervention, they should not drive for a week. Drivers holding a group 2 licence (lorries or buses) will be disqualified from driving once the diagnosis of angina has been made, and for at least six weeks after percutaneous coronary intervention. Re-licensing may be permitted provided the exercise test requirement (satisfactory completion of nine minutes of the Bruce protocol while not taking β blockers) can be met and there is no other disqualifying condition.

The ABC of interventional cardiology is edited by Ever D Grech and will be published as a book in summer 2003.

The diagram of the Angio-Seal device is used with permission of St Jude Medical, Minnetonka, Minnesota, USA. The angiogram showing the “candy wrapper” effect is reproduced with permission of R Waksman, Washington Hospital Center, and Martin Dunitz, London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Further reading

- • Smith SC Jr, Dove JT, Jacobs AK, Kennedy JW, Kereiakes D, Kern MJ, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines of percutaneous coronary interventions (revision of the 1993 PTCA guidelines)—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (committee to revise the 1993 guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty). J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37: 2215-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban Hayashi E, Perin M, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 2002;346: 1773-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Almond DG. Coronary stenting I: intracoronary stents—form, function future. In: Grech ED, Ramsdale DR, eds. Practical interventional cardiology. 2nd ed. London: Martin Dunitz, 2002: 63-76

- • Waksman R. Management of restenosis through radiation therapy. In: Grech ED, Ramsdale DR, eds. Practical interventional cardiology. 2nd ed. London: Martin Dunitz, 2002: 295-305

- • Kimmel SE, Berlin JA, Laskey WK. The relationship between coronary angioplasty procedure volume and major complications. JAMA 1995;274: 1137-42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Rensing BJ, Vos J, Smits PC, Foley DP, van den Brand MJ, van der Giessen WJ, et al. Coronary restenosis elimination with a sirolimus eluting stent. Eur Heart J 2001;22: 2125-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]