Abstract

Background

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM) are a key population for implementation of PrEP interventions. This open-label study examined adherence to PrEP and assessed sexual behavior among a diverse sample of YMSM in 12 U.S. cities.

Methods

Eligible participants were 18–22 year old HIV-uninfected MSM who reported HIV transmission risk behavior in the past 6 months. Participants were provided daily TDF/FTC (Truvada®). Study visits occurred at baseline, monthly through week 12, then quarterly through week 48. Dried blood spots (DBS) were serially collected for the quantification of tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP).

Results

Between March-September 2013, 2186 individuals were approached and 400 were found to be preliminarily eligible. Of those 400, 277 were scheduled for an in-person screening visit and 200 were enrolled (mean age=20.2; 54.5% Black, 26.5% Latino). Diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including urethral and rectal chlamydial/gonococcal infection and syphilis, at baseline was 22% and remained high across visits. At week 4, 56% of participants had TFV-DP levels consistent with ≥4 pills/week. By week 48, 34% of participants had TFV-DP levels consistent with ≥4 pills/week, with a noticeable drop-off occurring at Week 24. Four HIV seroconversions occurred on study (3.29/100 person-years). Condomless sex was reported by >80% of participants and condomless anal sex with last partner was associated with higher TFV-DP levels.

Conclusions

Acceptability of PrEP was high and most participants achieved protective drug levels during monthly visits. As visit frequency decreased, so did adherence. YMSM in the US may need PrEP access in youth-friendly settings with tailored adherence support and potentially augmented visit schedules.

INTRODUCTION

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM), particularly Black and Latino YMSM, are the group most impacted by HIV in the United States1, making them a key domestic population for implementation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) interventions. Based on evidence from multiple clinical trials of PrEP,2–4 the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approved daily use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) for the prevention of sexually-acquired HIV in July 2012. In anticipation of this new drug indication, several open-label demonstration projects were launched in order to evaluate PrEP safety and adherence outside of a placebo-controlled trial setting; effective PrEP implementation strategies for specific at-risk populations are also being evaluated.

While not placebo-controlled, the more recent PROUD study utilized an open-label, randomized controlled design of either immediate or delayed PrEP in order to pilot test the implementation of PrEP in the public health system of the United Kingdom through measurement of enrollment and retention as well as safety, adherence and behavioral disinhibition.5 The trial, which enrolled 544 MSM, was stopped early due to strong evidence of PrEP effectiveness leading the data safety monitoring board (DSMB) to recommend that all participants be offered immediate PrEP.

In addition to randomized trials, the iPrEx Open-Label Extension (OLE)6 study enrolled MSM and transgender women who were previously enrolled in the iPrEx randomized trial, as well as eligible participants from two other previously completed randomized PrEP trials: ATN 0827 and the CDC Safety Study.8 In total, 1603 participants enrolled in the study, of whom 76% decided to take PrEP. HIV incidence was strongly inversely correlated with PrEP adherence as measured by drug concentrations in dried blood spots (DBS) and there were no HIV infections among participants whose DBS drug levels were consistent with taking 4 or more pills per week. Additionally, drug concentrations were higher among older, more educated participants and those who reported condomless receptive anal intercourse, had more sexual partners, or had a history of syphilis or herpes.6

Most recently, the US PrEP Demonstration (DEMO) Project investigators reported outcome results from their trial of PrEP implementation for MSM and transgender women at municipal STI/community health clinics in 3 US cities (San Francisco, Miami and Washington, DC).9 Among the 557 participants enrolled, PrEP adherence was high with greater than 80% of those with drug levels testing via DBS demonstrating concentrations consistent with taking ≥4 doses/week at all visits. Incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) was high (90 per 100 person-years) but did not increase over time. Retention was higher among those who had previous knowledge of PrEP and self-reported condomless anal sex at baseline. Rates of adherence and engagement were significantly lower among African-American participants.10

Young men, particularly racial and ethnic minority youth, who are increasingly disproportionately impacted by HIV in the United States1 were under-represented in each of the aforementioned studies. Young people under the age of 25 made up only about 20% of both the iPrEx OLE and DEMO Project samples, and the median age of participants in both the DEMO Project and PROUD was 35 years. With evidence that medication adherence is known to be a significant challenge for adolescents and young adults,11–14 including adherence to PrEP,6,7,15 PrEP trials specifically focused on youth under age 25 are critical for the development of successful PrEP implementation strategies.

Additionally, despite the absence of evidence of behavioral disinhibition in adult PrEP trials, concerns about young people using PrEP continue to be raised.16 The potential for decreased adherence and increased sexual risk highlights the need for integrated behavioral interventions with PrEP programming as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package in vulnerable populations of youth. Given the absence of any youth-specific PrEP demonstration projects, we built on the information learned from our previous PrEP pilot with YMSM7 and designed Project PrEPare 2, an open label demonstration project and phase II safety study of PrEP among young MSM ages 18–22 (ATN 110). The primary objectives of this study were to 1) provide additional safety data regarding TDF/FTC use among HIV-uninfected young MSM, 2) examine acceptability, patterns of use, rates of adherence and measured levels of drug exposure when YMSM are provided open label TDF/FTC (Truvada®), and 3) examine patterns of risk behavior when YMSM are provided with an evidence-based risk reduction behavioral intervention prior to starting PrEP.

METHODS

Overview

This open label PrEP demonstration project and safety study provided PrEP along with evidenced-based behavioral HIV prevention interventions [Many Men, Many Voices – 3MV17 and Personalized Cognitive Counseling – PCC18 to young MSM at study sites for the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) across the United States. Study sites were located in 12 urban US cities (Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Memphis, Miami, New Orleans, Philadelphia and Tampa) with substantial prevalence of HIV infection among young people.19 All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating study site.

Participants

Multiple recruitment methods were employed across sites, including street and venue-based outreach, community and school presentations, and online advertising on social media websites and social networking applications (“apps”). Eligibility data were collected through screening tools programmed on mobile devices (i.e., Apple iPod Touch) and web-based forms and documented on recruitment logs.

HIV-uninfected YMSM, who were born male and were 18 through 22 years of age at the time of signed informed consent, were eligible to enroll in the study. Participants had to report HIV transmission risk behavior (e.g. condomless anal intercourse, multiple sexual partners, recent STI), test HIV-negative at time of screening, be willing to provide contact information, take TDF/FTC as PrEP, and participate in one of the two behavioral interventions. Potential participants were ineligible if they had a history of unexplained bone fractures; had presence of hepatitis B surface antigen; had creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 75 mL/min calculated based on the Cockroft-Gault equation; had confirmed ≥ Grade 2 serum phosphate, hematologic or hepatobiliary chemistry abnormality; confirmed proteinuria or normoglycemic glucosuria; confirmed Grade ≥ 3 toxicity on any screening evaluations; known allergy/sensitivity to the study agent or its components; or concurrent participation in an HIV vaccine study or other investigational drug study, including oral or topical PrEP (microbicide) studies.

Procedures

After participants completed the informed consent process, were confirmed to be eligible and completed their baseline study visit, they were scheduled to attend the behavioral intervention assigned to their site. These interventions were chosen because they are identified as effective HIV risk reduction interventions in the CDC’s Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBI) program20 and CDC-trained professionals were locally available in each city. Once participants completed the behavioral intervention, they were scheduled for the Week 0 visit at which they received additional PrEP education and were dispensed a 30-day supply of the study drug with instructions to take one tablet daily. TDF/FTC tablets were supplied by Gilead Sciences, Inc. in Foster City, CA, USA.

Study visits occurred monthly for the first quarter (Weeks 4, 8 & 12), then quarterly thereafter through 48 weeks. At each visit, behavioral and biomedical data were collected. A medical history, including review of signs and symptoms, and a symptom-directed physical exam were conducted at each visit. Laboratory evaluations included FDA-approved HIV antibody testing, urine nucleic-acid amplification testing (NAAT) for gonorrhea (GC) and Chlamydia trachomitis (CT), self-administered rectal swabs for GC/CT NAAT, rapid plasma regain (RPR), hepatitis B surface antigen, renal, liver and pancreatic function chemistry tests and urine dipstick testing for protein and glucose. Blood collected as dried blood spots (DBS) at each visit was shipped to the University of Colorado for quantification of tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) levels. Participants also completed spine, hip and whole body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans at baseline, week 24 and week 48.

All participants received a comprehensive package of HIV prevention services at each visit (i.e., risk reduction counseling, condoms, symptomatic STI screening and treatment) and met with a study counselor to complete an Integrated Next Step Counseling (iNSC) session.21 The iNSC approach includes exploration, problem solving and skills building around non-biomedical strategies to prevent HIV, and for those receiving PrEP, assesses participant’s desire to remain on PrEP and strategies to improve or maintain adherence.37,38 At each study visit, participants completed behavioral assessments via audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI), received condoms, and were dispensed study drug. Participants were provided compensation for each study visit as determined by each local IRB.

Measures

PrEP Acceptability

Assessments of acceptability were conducted at the Week 12 and 48 study visits. This instrument, which has been used in a past PrEP study with youth, assesses: 1) the usability of PrEP; 2) the user-friendliness of the medication regimen, including an assessment of side effects and dosing frequency; and 3) the acceptability of behavioral intervention sessions.7 Beliefs about PrEP were assessed using nine questions adapted from the iPrEx OLE6 study in order to explore the potential ways that PrEP may influence subjects’ health, condom use, sexual behavior as well as reasons that subjects would chose not to take PrEP.

Adherence

The AIDS Clinical Trial Group Adherence Follow-up Questionnaire12 was adapted to examine the possible reasons for missing PrEP doses. The questionnaire presents a number of possible reasons for missed doses and asks subjects to rate how often they have missed taking their medications over the past month due to these reasons. PrEP Medication Levels were assessed via Dried Blood Spots (DBS) collected at each visit to quantify intracellular TFV-DP and FTC-TP concentrations.22 DBS results were translated into dosing categories previously used in PrEP trials with adult MSM.6 Dosing categories included below lower limit of quantitation (BLQ), lower limit of quantitation to 349 fmol per punch (fewer than two tablets per week), 350–699 fmol per punch (two to three tablets per week), ≥ 700fmol per punch (four or more tablets per week).

Sexual Behavior

A self-report questionnaire was used to assess each participant’s overall sexual behavior history as well as in-depth analysis of the sexual behavior that occurred with the last sexual partner. Participants were also routinely tested for syphilis at baseline and week 48, and as clinically indicated at other visits. Rectal swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia were routinely collected at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks and as clinically indicated at other visits. Urine-based testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia occurred at every visit. Participants were defined as STI positive if they tested positive for urethral or rectal GC or CT and if they had evidence of acute syphilis (defined as positive RPR with titers along with review of past diagnoses/treatment).

Data and Safety Monitoring

The Protocol Team monitored the study for clinical adverse events (AE) and abnormal laboratory values using the ATN Table for Grading Severity of Adolescent Adverse Events (October 2006 – Clarification March 2011). Expedited Adverse Event (EAE) reporting followed standard reporting requirements as defined in the Manual for Expedited Reporting of Adverse Events to ATN/NICHD, version 2.0, March 2011. Social harms were recorded on case report forms at the site and entered into the database electronically. An external DSMB reviewed study safety data six times at 6-month intervals during trial implementation, and recommended that the study continue to completion.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographics, number of adverse events, rates of toxicity, rates of acceptability, patterns of use, rates of adherence, measured levels of drug exposure, and patterns of risk behavior were summarized using frequencies, means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges as appropriate. BMD Z-scores were generated by the DXA software using population norms. Risk behaviors were compared between youth who were adherent to PrEP (≥4 pills/week) and those who were non-adherent (<4 pills/week) over time by generalized estimating equations (GEE), to adjust for multiple measurements within subjects, with a logit link and binomial distribution. Generalized estimating equations were also used to test for trend in STI diagnoses over time and whether the TFV-DP levels over time differed by status of engaging in recent condomless sex or self-reported condomless receptive anal sex with their last partner. Incidence was calculated as the number of seroconversions divided by the total number of person-years on PrEP. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS,23 and p< 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

Recruitment and Participant Retention

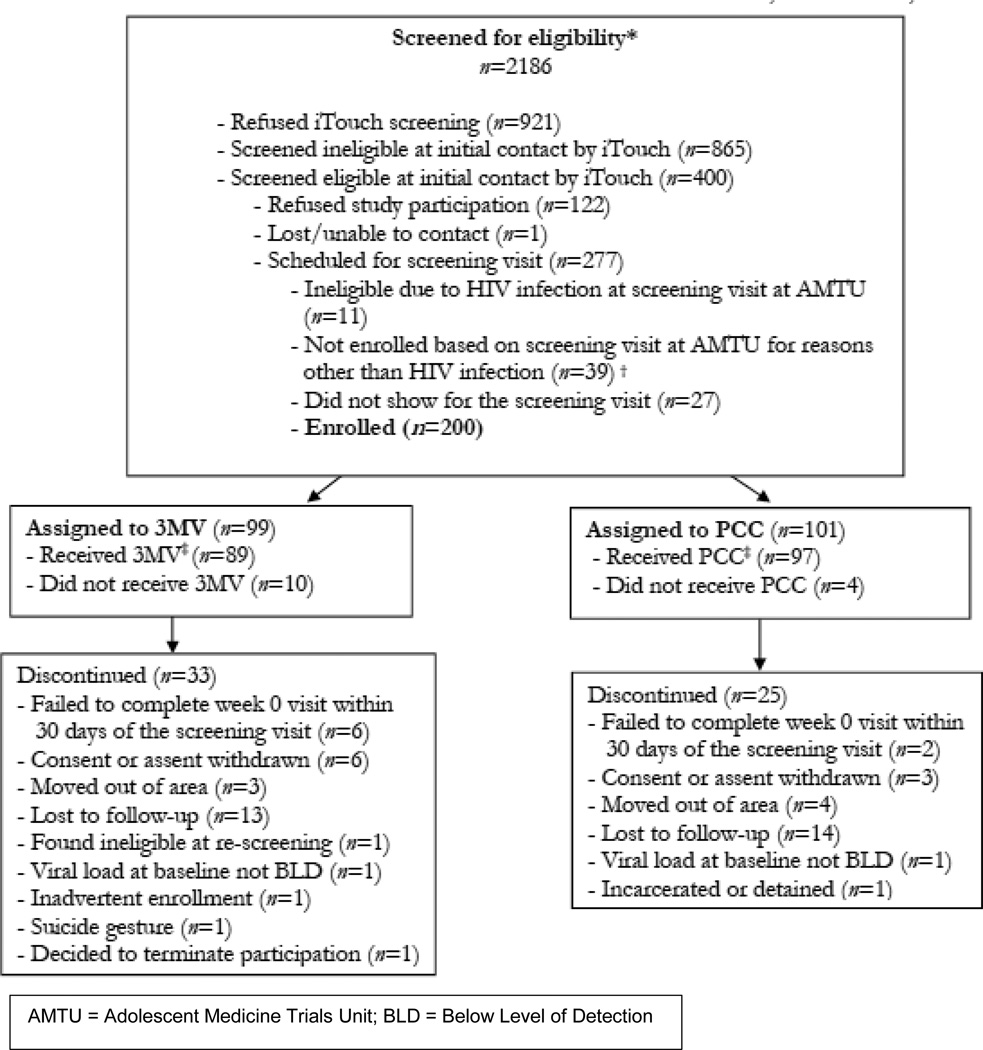

From January to September 2013, 2,186 individuals were screened for eligibility in the field and 400 were found to be preliminarily eligible. Of those, 277 were interested in study participation and were scheduled for the clinic-based screening visit. Eleven individuals (4%) were found ineligible at the screening visit due to undiagnosed HIV infection, 27 failed to attend the screening visit, and 39 were ineligible for other reasons (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Two hundred youth (n=200) with a median age of 20, were enrolled into the study. Twenty-six percent of the participants (n=53) self-identified as Latino. Of non-Latinos, the majority of participants identified their race as Black/African-American (66%), with an additional 29% identifying as white, 3% as mixed race and 2% Asian/Pacific Islander or American Indian. Most participants identified as either gay (77.8%) or bisexual (13.7%). Almost half (45.5%) of the young men had completed some college education, and 30.1% were currently unemployed. Just over 15% of participants reported that they had been homeless in their lifetime and 28.6% reported experience with exchanging sex for money (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Data

| Overall | |

|---|---|

| n | 200 |

| Age at Baseline (years) | |

| Mean | 20.2 |

| Std | 1.3 |

| Median | 20.0 |

| Race (%) | |

| Black/African American | 93 (46.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (1.0) |

| White/non-Hispanic | 42 (21.0) |

| White/Hispanic | 21 (10.5) |

| Other/Mixed Race | 42 (21.0) |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 53 (26.5) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 145 (72.5) |

| Condomless sex past month | 80.79% |

| Condomless receptive anal intercourse w/last partner |

57.98% |

| Any positive STI test | 22% |

| Ever kicked out of house due to sexual orientation |

17.2% |

| Ever spent at least one night in homeless shelter |

15.5% |

| Ever exchanged sex for money | 28.6% |

Fifty-eight participants were prematurely discontinued from the study. The most common reason was loss to follow-up (n=34) followed by withdrawal of consent (n=9) and moving out of the area (n=7). In addition, 2 participants were prematurely discontinued due to diagnosis with acute HIV infection identified by HIV RNA assay at the baseline visit. Overall study retention was 71%, including premature discontinuations and those who were lost to follow-up. For those that remained on study, visit retention was very high at 91.8% of all expected visits.

Safety

There were three Grade 3 adverse events (nausea, weight loss, headache) among three participants that were deemed to be related to the study drug, all of which fully resolved when medication was discontinued. Only a single renal event, a Grade 1 elevation of serum creatinine, was noted at the last study visit and resolved by the subsequent safety follow-up visit. An additional 21 Grade 3 or higher adverse events that were deemed unrelated to study drug occurred among 15 participants. Twenty-two participants decided to discontinue study drug (median time on PrEP was 0.35 years), but stay on the study, primarily due to personal choice or self-reported side effects, including gastrointestinal discomfort.

At baseline, median BMD Z-scores among participants were below zero (spine −0.50, hip −0.45, WB −0.40), suggesting lower bone mass than would be expected in healthy young men. Between baseline and week 24, BMD decreased modestly but significantly in the hip (median −0.44%, P<0.001) and whole body (−0.61%, P<0.001); and tended to decrease in the spine (−0.23%, P=0.11). Decreases in all Z-scores were statistically significant (median absolute changes in Z-score in spine −0.10, P<0.001; hip −0.02, P=0.017; WB −0.10, P<0.001). Between weeks 24 and 48, hip BMD and Z-score continued to decline significantly, but no further significant losses were seen in the spine or whole body.

Two social harms reported were deemed related to participation in the study. In one case, a participant was coerced to have condomless sex with his HIV-positive partner because he was on PrEP. The second social harm involved a parent threatening to evict the participant from the home if he didn’t stop taking PrEP. In both cases, participants were linked directly to appropriate counseling.

Acceptability

When asked at Week 48 about acceptability of the study procedures, including HIV/STI testing, physical exams, and behavioral counseling, over 90% of participants “liked” or “liked them a lot”. Regarding the acceptability of the TDF/FTC pill, one-third of participants didn’t like the size of the pill and over half (52.2%) didn’t like the taste of the pill. Nevertheless, most (60.3%) found taking a pill every day to be acceptable. There were no significant changes from week 12 to week 48.

Medication Adherence

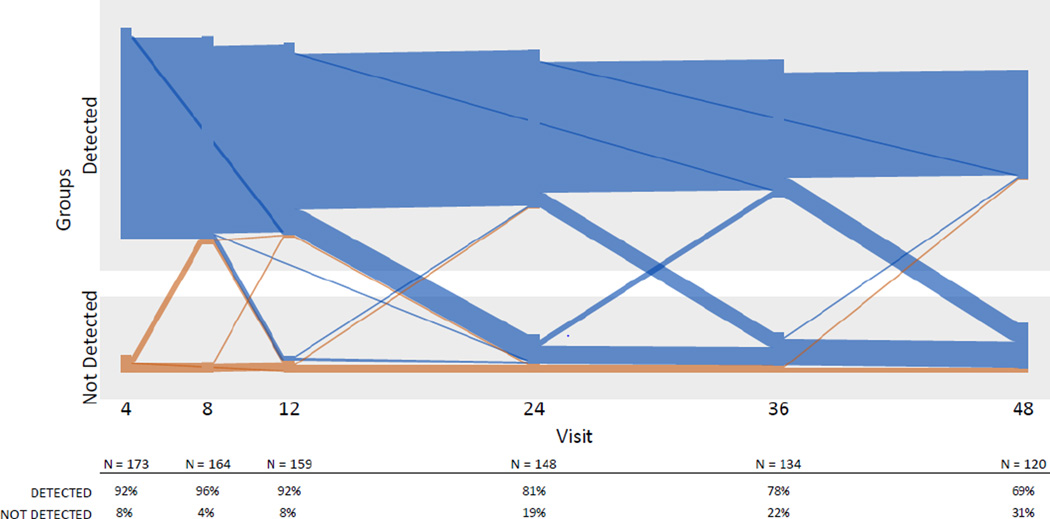

DBS TFV-DP demonstrated that the majority of participants had detectable drug over the course of the study, with over 90% of participants having detectable drug through the first 12 weeks, 81% at week 24 and 69% at week 48 (Figure 2). Quantitative analysis of TFV-DP levels demonstrated a similar pattern of decline over time: the majority of participants had TFV-DP levels consistent with ≥4 pills/week over the first 12 weeks of the study, a noticeable drop-off occurred at Week 24, and by week 48, only 34% of participants had this level of drug detected (Figure 3). Median levels for African-American participants were below the protective threshold of ≥4 pills/week at all time points.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal drug detection in plasma in the ATN 110 cohort, by individual participant and visit week

Lines in blue and orange represent participants who had drug detected and not detected respectively at the earliest follow-up visit with drug level testing. Plasma was tested every 4 weeks up to Week 12 and every 12 weeks up to Week 48. Overall declining Ns reflect fewer individuals with longer duration of follow-up due to enrolling on a later date, as well as loss to follow-up (approximately 29% of participants had an early termination visit).

Figure 3.

Tenofovir diphosphate levels (fmol/punch) and PrEP dosing estimates as measured by dried blood spot assay

The most common overall reasons reported by participants for missing study pills were that they “often” or “sometimes” simply forgot (28.5%), were away from home (27.3%), or too busy with other things (26.7%). A few participants reported that they missed medication because they wanted to avoid side effects (4.48%), did not want others to see them taking the medication (2.47%), or they believed the pill was harmful (1.9%).

There were several statistically significant differences in beliefs about PrEP by whether participants were categorized as adherent (≥4 pills/week) or non-adherent (<4 pills/week). Adherent participants worried less about getting HIV (p=0.01), felt more comfortable having sex with an HIV-positive partner (p=0.01), and feared developing medication resistance if they contracted HIV (p=0.004) compared to non-adherent participants. Significantly more non-adherent participants reported not liking taking pills than adherent participants (p=0.02).

Sexual Risk Behavior and Risk Compensation

At enrollment, 81% of participants reported condomless sex with a partner in the past month and 58% reported condomless receptive anal sex with their last partner. Participants reported an average of 5 sexual partners in the past month and 22% of participants were diagnosed with an STI at baseline. The overall STI incidence rate on study was 66.44 (95% CI: 50.53 – 82.35), with greater STI incidence in the first 24 weeks of study (76.48/100 person years) than the latter half of the study (60.99/100 person years). An additional indicator of HIV exposure – post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) prescriptions – also remained stable with one or zero participants requesting PEP at each study visit week.

We also examined the relationship between HIV sexual risk behavior and pill adherence. For participants who reported engaging in recent condomless sex, TFV-DP levels were consistently higher (p=0.01) and remained higher over the course of the study. A similar, yet not statistically significant, trend for higher TFV-DP was seen among participants that reported condomless receptive anal sex with their last partner.

Four HIV seroconversions occurred during the study (one each at weeks 4, 32, 40 & 48) for an HIV incidence rate of 3.29 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.07 – 6.52). None of the participants who seroconverted had detectable levels of TFV-DP in the sample that was drawn closest to the seroconversion date (Figure 4). All participants who seroconverted were immediately linked to medical care and no antiretroviral drug resistance was detected.

Figure 4.

Tenofovir diphosphate levels among seroconverters by study week until seroconversion (*)

DISCUSSION

This study, which enrolled the youngest and most diverse cohort of young MSM of any domestic PrEP study to date, provides critical safety and adherence data for youth who are at greatest risk for HIV infection in the United States. While loss-to-follow rates did increase over time, possibly reflecting the chaotic and mobile nature of youths’ lives, participants reported high acceptability of many of the study components. Despite the loss-to-follow up, the ratio of expected to actual visits was very high and likely a reflection of the culturally-competent and youth-friendly sites utilized for this study.

Low bone mineral density (BMD) at baseline was not unexpected, particularly among YMSM from racial and ethnic minority communities. While the causes are not yet explained, lower than expected BMD Z-scores at baseline have been seen in other studies of HIV-negative at-risk men.24–27 However, despite the absence of any significant bone events on study, loss before attainment of peak bone mass in such young men who are starting out with low BMD may raise the risk for potential fragility in adulthood and merits further investigation. An extended follow up of such individuals who met pre-defined safety criteria at the end of this study is currently underway to determine the extent of how reversible these changes may be. That said, the absence of any significant renal toxicities or other clinical adverse events among participants was reassuring, though renal injury from TDF may require longer exposure than participants experienced in this study.

Adherence to the daily medication regimen waned over time but most participants were able to achieve protective levels of PrEP for the first quarter of the study and very few participants had undetectable drug levels overall. These adherence rates are an improvement to a previous youth-focused PrEP trial7 and demonstrate that these participants tried to take PrEP as directed. However, as has consistently been shown in the literature, rates of medication adherence among youth are often far below rates seen in adults and tend to decline over time,28 indicating that youth-specific adherence intervention strategies are still needed. Adherence “boosters”, such as text messaging or check-in calls that have been successful in improving adherence to treatment for HIV-positive youth, could potentially prove useful for PrEP.29, 30 Of further note was the decline in adherence seen as study visit intervals increased from monthly to quarterly. Other pediatric and adolescent specialties have documented the relationship between visit frequency, improved adherence, and better health outcomes.31,32,33 It may also be the case that clinical schedules for PrEP care need to be flexible and a more developmentally-appropriate approach could be to see young people more frequently. Studies to evaluate alternative visit schedules for PrEP implementation among youth are needed.

Consistent with other recent PrEP demonstration studies,5,6,10 baseline rates of HIV transmission risk behavior and sexually transmitted infections were very high among participants enrolled in this study, and these behaviors remained largely stable over time. Although this suggests that behavioral disinhibition was uncommon, it also suggests that risk maintenance remained high, and underscores the importance of PrEP and adherence counseling for HIV prevention in YMSM. The identification of previously undiagnosed prevalent cases of HIV (4%) during screening for this study, as well as 2 acute HIV infections and their expedient linkage to life saving care, is an important public health advantage of PrEP programs.

The most concerning finding in this study was the adherence discrepancies seen among those that identified as black/African-American compared to participants of other racial/ethnic groups. Unfortunately, this finding is consistent with recent research highlighting lack of exposure to HIV prevention interventions, and PrEP in particular, by BYMSM.34,35,36 In-depth analyses are needed to further our understanding of potential racial differences in DBS pharmacokinetics, as well as the historical, societal, behavioral and attitudinal barriers to PrEP access and adherence among those most impacted in the US – black/African-American young MSM.

In conclusion, the ATN 110 study, the first entirely youth-focused open label PrEP trial, enrolled a highly diverse sample of YMSM who demonstrated elevated vulnerability to HIV and levels of reported risk behavior remained relatively constant throughout the study. Among those youth who were eligible for the study, uptake of PrEP was very high and the majority of participants achieved protective drug levels (≥ 4 pills per week) during monthly visits. As the study visits decreased in frequency, adherence to the daily PrEP regimen declined. The striking racial disparities in adherence indicate that much more work is needed in order to understand and implement PrEP in a way that is culturally-competent. Finally, given the number of STI diagnoses while on study, HIV infections among this cohort would likely have been much higher in the absence of PrEP.

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) from the National Institutes of Health [U01 HD 040533 and U01 HD 040474] through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (B. Kapogiannis and S. Lee), with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (K. Davenny and S. Kahana) and Mental Health (P. Brouwers, S. Allison). Study drug was donated by Gilead Sciences. The study was scientifically reviewed by the ATN’s Community Prevention Leadership Group. Network, scientific, and logistical support was provided by the ATN Coordinating Center (C. Wilson and C. Partlow) at The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Network operations and data management support was provided by the ATN Data and Operations Center at Westat, Inc. (J. Korelitz and B. Driver). The authors acknowledge the contribution of the investigators and staff at the following sites that participated in this study: University of South Florida, Tampa (Emmanuel, Straub), Children’ s Hospital of Los Angeles (Belzer, Tucker), Children’ s Hospital of Philadelphia (Douglas, Tanney, DiBenedetto), John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County and the Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center (Martinez, Bojan, Jackson), Tulane University Health Sciences Center (Abdalian, Kozina, Baker), University of Miami School of Medicine (Friedman, Maturo, Major-Wilson), St. Jude’ s Children’ s Research Hospital (Flynn, Gaur, Dillard), Baylor College of Medicine (Paul, Calles, Cooper), Wayne State University (Secord, Cromer, Green-Jones), John Hopkins University School of Medicine (Agwu, Anderson, Park), The Fenway Institute—Boston (Mayer, George, Dormitzer), and University of Colorado Denver (McFarland, Reirden, Hahn). Drug concentrations were assayed at the Colorado Antiviral Pharmacology Laboratory (Lane Bushman, Jia-Hua Zheng, L Anthony Guida, Becky Kerr, Brandon Klein). The investigators are grateful to the members of the local Youth Community Advisory Boards for their insight and counsel and are particularly indebted to the young men who participated in this study for their willingness to share their lives and their time with us.

Sources of Funding: This study was funded under cooperative agreements U01 HD040533 and U01 HD040474 from the National Institutes of Health through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with supplemental funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute of Mental Health. Study drug was donated by Gilead Sciences, Inc, along with supplemental funds for a portion of the dried blood spot testing. The comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Mayer has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead Sciences and ViiV. Dr. Mayer has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead Sciences and ViiV. Dr. Anderson receives donated study drug and contract work from Gilead.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. HIV Among Youth. 2015 Jun 30; www.cdc.gove/hiv/group/ageyouth.

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Partners PrEP Study Team. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. TDF2 Study Group. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;15:S0140–S6736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, Hosek S, Mosquera C, Casapia M, Montoya O, Buchbinder S. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2014 Sep 30;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosek SG, Siberry G, Bell M, et al. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV Interventions. Project PrEPare (ATN 082): The Acceptability and Feasibility of an HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Trial with Young Men who Have Sex With Men (YMSM) JAIDS. 2013;62(4):447–456. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182801081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (tdf) among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:79–86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828ece33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):439–448. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Anderson PL, Doblecki-Lewis S, Bacon O, Chege W, Postle BS, Matheson T, Amico KR, Liegler T. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal-and Community-based sexual health services. JAMA internal medicine. 2015 Nov;:1–1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg KM, Arnsten JH. Practical and conceptual challenges in measuring antiretroviral adherence. JAIDS. 2006;1(43):S79–S876. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248337.97814.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesney MA, Morin M, Sherr L. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1599–1605. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, et al. Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected youth in the United States: a study of prevalence and interactions. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2009;23(3):185–194. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsey JC, Bosch RJ, Rudy BJ, Flynn PM. Early patterns of adherence in adolescents initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy predict long-term adherence, virologic, and immunologic control. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(10):799–801. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. JAIDS. 2010;54(5):548–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e19a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilton L, Herbst JH, Coury-Doniger P, et al. Efficacy of an HIV/STI prevention intervention for black men who have sex with men: findings from the Many Men, Many Voices (3MV) project. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:532–544. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Loeb L, et al. Brief cognitive counseling with HIV testing to reduce sexual risk among men who have sex with men: results from a randomized controlled trial using Paraprofessional Counselors. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;44(5):569–577. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318033ffbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes W, D'Angelo L, Yamazaki M Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Identification of HIV-infected 12- to 24-year-old men and women in 15 US cities through venue-based testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):273–276. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Diffusion of Effective Interventions (DEBI) Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/index.html.

- 21.Chianese C, Amica KR, Mayer K, et al. Integrated Next Step Counseling for Sexual Health Promotion and Medication Adherence for Individuals Using Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2014;30:A159-A159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, Rower JE, Meditz A, Gardner EM, Predhomme J, Fernandez C, Langness J, Kiser JJ, Bushman LR, Anderson PL. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2013 Feb 1;29(2):384–390. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS Institute Inc. SAS® 9.3 Macro Language: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. Effects of emtricitabine/tenofovir on bone mineral density in HIV-negative persons in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: DXA results from iPrEx. Clin Infec Dis. 2015;61:572–581. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulligan K, Harris DR, Emmanuel P, et al. Low bone mass in behaviorally HIV-infected young men on antiretroviral therapy: Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) Study 021B. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:461–468. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grijsen ML, Vrouenraets SM, Wit FW, et al. Low bone mineral density, regardless of HIV status, in men who have sex with men. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:386–391. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Bone mineral density in HIV-negative men participating in a tenofovir pre-exposure prophylaxis randomized clinical trial in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zindani GN, Streetman DD, Streetman DS, Nasr SZ. Adherence to treatment in children and adolescent patients with cystic fibrosis. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.013. J Adolesc Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garofalo R, Kuhns LM, Hotton A, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Personalized Text Message Reminders to Promote Medication Adherence Among HIV-Positive Adolescents and Young Adults. AIDS and Behavior. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finitsis DJ, Pellowski JA, Johnson BT. Text message intervention designs to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e88166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison F, Shubina M, Turchin A. Encounter frequency and serum glucose level, blood pressure, and cholesterol level control in patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1542–1550. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turchin A, Goldberg SI, Shubina M, Einbinder JS, Conlin PR. Encounter frequency and blood pressure in hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2010;56(1):68–74. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.148791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guthmann R, Davis N, Brown M, Elizondo J. Visit frequency and hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2005;7(6):327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eaton Lisa A, et al. Minimal awareness and stalled uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among at risk, HIV-negative, black men who have sex with men. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2015;29(8):423–429. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khanna AS, Michaels S, Skaathun B, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis Awareness and Use in a Population-Based Sample of Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):136–138. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelley Colleen F, et al. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(10):1590–1597. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amico KR, McMahan V, Goicochea P, Vargas L, Marcus JL, Grant RM, Liu A. Supporting study product use and accuracy in self-report in the iPrEx study: next step counseling and neutral assessment. AIDS and Behavior. 2012 Jul 1;16(5):1243–1259. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, Hosek S, Mosquera C, Casapia M, Montoya O, Buchbinder S. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. The. Lancet infectious diseases. 2014 Sep 30;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]