Abstract

Objectives

Mandatory employer-based insurance coverage of contraception in the U.S. has been a controversial component of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Prior research has examined the cost effectiveness of contraception in general; however, no studies have developed a formal decision-model in the context of the new ACA provisions. As such, this study aims to estimate the relative cost effectiveness of insurance coverage of contraception under employer-sponsored insurance coverage taking into consideration newer regulations allowing for religious exemptions.

Study Design

A decision-tree was developed from the employer perspective to simulate pregnancy costs and outcomes associated with insurance coverage. Method-specific estimates of contraception failure rates, outcomes, and costs were derived from the literature. Uptake by marital status and age was drawn from a nationally-representative database

Results

Providing no contraception coverage resulted in 33 more unintended pregnancies per 1000 women (95% Confidence Range: 22.4; 44.0). This subsequently significantly increased the number of unintended births and terminations. Total costs were higher among uninsured women owing to higher costs of pregnancy outcomes. The effect of no insurance was greatest on unmarried women 20–29 years old.

Conclusions

Denying female employees full coverage of contraceptives increases total costs from the employer perspective, as well as the total number of terminations.

1. Introduction

Current contraceptive methods are efficacious,[1] safe,[2] and cost effective.[3] The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a provision to expand coverage of contraception through mandated employer-sponsored insurance for women and families at no cost-sharing to employees. The ACA’s expansion of insurance coverage for contraceptive services is predicted to improve women’s health and reduce unintended pregnancies. [4] In addition, the expansion of contraception coverage under the ACA has been predicted to result in approximately 25,000 fewer abortions annually.[5] The uptake of contraceptive methods by insurance status is available via national databases, however, the cost-effectiveness of private, employer-sponsored insurance coverage of contraception is unknown.

More than half of all pregnancies in the U.S. are unintended, the majority of which occur among low-income women and women aged 18–24 years old.[6, 7] Costs resulting from unintended pregnancies are burdensome for the government and individual taxpayers: in 2006, an estimated $11.6 billion in public funds were spent on births that resulted from unintended pregnancies.[8] In addition, unintended pregnancies may be costly for employers who provide insurance to their employees through private health plan contracts. Private health plans may spend as much as $4.6 billion in costs related to unintended pregnancies each year.[9]

Prior research has examined the cost-effectiveness of contraception in general and found it to be a highly cost-effective healthcare strategy.[3] Additional studies have found contraception coverage to be cost-effective and even cost-saving from the perspective of public insurers.[10, 11] However, to our knowledge, no studies have developed a formal decision-model of private insurance coverage for contraception in the context of the new ACA provisions. This study aims to estimate the impact on pregnancies, pregnancy outcomes and costs of private, employer-sponsored insurance coverage for contraceptives.

2. Material and Methods

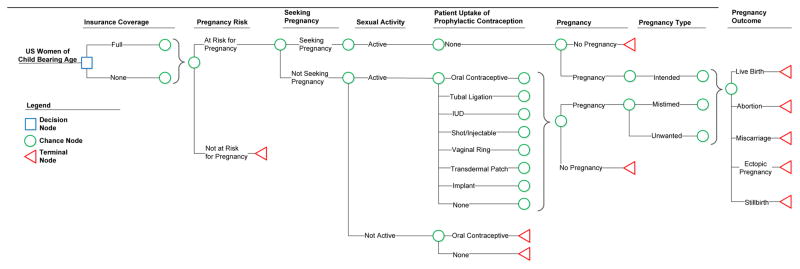

A decision model was developed from the employer perspective to simulate costs and outcomes associated with employer-sponsored coverage of contraception methods as mandated by the ACA. (Figure 1) The model simulates a cohort of 1 million women either offered 1) full contraceptive coverage through an employer-sponsored private health insurance plan or 2) no coverage to estimate the effect of complete contraceptive coverage on US women of childbearing age. The model includes 7 sequential decision points: pregnancy risk, pregnancy seeking status, sexual activity, uptake of various methods of contraception, pregnancy, pregnancy intendedness, and pregnancy outcome. Sexual activity, contraception uptake, pregnancy, intendedness, and pregnancy outcomes were modified by patient age and current marital status, since they are potentially influential demographic characteristics.[12, 13] Age and marital status distributions were determined from the 2010 U.S. census.[14–16] Women in the model were assumed to have up to a year of exposure to contraception. The number of pregnancies that resulted during this one-year time horizon were then followed to final outcome, even if the outcome were to occur sometime beyond the one-year time frame. The model was developed in Microsoft ExcelTM (Redmond, WA).

FIGURE 1.

Decision Model Structure

2.1. Probability of Events and Health Outcomes

Joint probabilities for key patient characteristics described in our model - sexual activity by marital status and choice of contraceptive method by insurance status, sexual activity and marital status-were derived through descriptive analysis of National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) survey data.[17] The NSFG is a federally funded, nationally representative annual survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that gathers information on marriage, divorce, family life, infertility, pregnancy, and use of contraception. The 2006–2010 cycle of the NSFG includes surveys with over 12,000 women of reproductive age (ages 15–44). For our analytic approach, we first replicated a descriptive report of similar patient characteristics published by the NSFG to ensure consistency with established methods.[12] We then estimated sample-weighted frequencies for the probabilities required by our model. All analyses were conducted using Stata (Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

The NSFG defines sexually active women as those who have had sex in the past three months. Sexually inactive women are defined as those who have never had intercourse since their first period or those who have had intercourse, but not in the past three months. To prevent overestimating the effect of contraceptive coverage on pregnancy outcomes, we combined this binary definition of sexual activity with pregnancy status to identify the following probabilities: (1) Not at risk for pregnancy (currently pregnant, post-partum, received tubal ligation or partner had vasectomy, or sterile for non-contraceptive reasons); (2) Sexually active, able to become pregnant, but not seeking pregnancy; (3) Sexually active, able to become pregnant, and seeking pregnancy; (4) Sexually inactive. We used a categorical age variable with 5-year age increments. Marital status was defined as a binary variable of (1) currently married, or (2) not currently married (includes those not married but living with opposite sex partner; widowed; divorced; separated; and never been married). Probabilities of contraceptive uptake by method included the proportion of women using each type of contraception during the month of their NSFG interview. The set of contraceptive methods included in uptake were based on prior cost-effectiveness analyses in the literature (Table 1).[3] Women not using contraception were defined by the NSFG as those who had intercourse in the past three months, but reported using no contraceptive method. To avoid overestimating the number of women who might experience an unintended pregnancy with or without insurance coverage, we modeled frequencies for contraception uptake excluding women who were seeking pregnancy, currently pregnant, post- partum, or sterile for contraceptive or non-contraceptive reasons. In addition, we excluded from contraceptive uptake those women who relied on their partner’s vasectomy for contraception. These women were included in all other components of the model.

Table 1A.

Base-Case Assumptions and Ranges for Sensitivity Analysis (%)

| Variable | Value | Range | Distribution | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Demographics | ||||

| Age Distribution | ||||

| 15–19 | 17.8 | 16.9, 18.6 | Dirichlet | [34] |

| 20–24 | 16.8 | 15.9, 17.6 | Dirichlet | [34] |

| 25–29 | 16.8 | 15.9, 17.6 | Dirichlet | [34] |

| 30–34 | 15.8 | 15.0, 16.5 | Dirichlet | [34] |

| 35–39 | 16.3 | 15.4, 17.1 | Dirichlet | [34] |

| 40–44 | 16.8 | 15.9, 17.6 | Dirichlet | [34] |

| Married by Age | ||||

| 15–19 | 3.1 | 3.0, 3.3 | Beta | [34] |

| 20–24 | 15.0 | 14.3, 15.8 | Beta | [34] |

| 25–29 | 41.1 | 39.1, 43.2 | Beta | [34] |

| 30–34 | 60.5 | 57.5, 63.5 | Beta | [34] |

| 35–39 | 68.3 | 64.9, 71.7 | Beta | [34] |

| 40–44 | 69.1 | 65.7, 72.6 | Beta | [34] |

| Sexually Active by Age | ||||

| 15–19 | 41.5 | 39.4, 43.6 | Beta | [12] |

| 20–24 | 80.5 | 76.5, 84.5 | Beta | [12] |

| 25–29 | 89.9 | 85.4, 94.4 | Beta | [12] |

| 30–34 | 91.5 | 86.9, 96.1 | Beta | [12] |

| 35–39 | 92.4 | 87.8, 97.0 | Beta | [12] |

| 40–44 | 90.8 | 86.3, 95.3 | Beta | [12] |

| Contraception Failure Rate | ||||

| No Method | 85.0 | 68.0, 100.0 | Beta | [1] |

| Oral contraception | 9.0 | 7.2, 10.8 | Beta | [1] |

| Intrauterine Device | 0.5 | 0.4, 0.6 | Beta | [1] |

| Shot/ Injectable | 0.1 | 0.1, 0.1 | Beta | [1] |

| Vaginal Ring | 9.0 | 7.2, 10.8 | Beta | [1] |

| Transdermal Patch | 9.0 | 7.2, 10.8 | Beta | [1] |

| Implant | 0.1 | 0.1, 0.1 | Beta | [1] |

| Male condom | 18.0 | 14.4, 21.6 | Beta | [1] |

| Withdrawal | 22.0 | 17.6, 26.4 | Beta | [1] |

| Fertility awareness | 24.0 | 19.2, 28.8 | Beta | [1] |

| Other | 16.2 | 13.0, 19.4 | Beta | [1] |

Contraceptive method uptake by insurance status was estimated for each insurance arm (private insurance vs. no insurance) in the model using an NSFG variable for current health insurance status, where private insurance was defined as women currently covered by private health insurance or Medi-Gap plans and no insurance was defined as women currently covered only by a single-service plan (i.e., plans that do not normally provide for comprehensive or routine health care services), only by the Indian Health Service, or currently not covered by health insurance. Women on public health insurance were intentionally excluded from this analysis as we were focusing solely on the effect of private health insurance. We estimated joint probabilities of contraceptive method uptake by insurance status, age, and sexual activity. It is unreasonable to assume that, under no insurance, a high number of women would purchase long-acting reversible contraception methods (i.e., implants and intra-uterine devices) due to their large upfront costs.[18] Therefore, uninsured women using LARCs were assumed to have received them when previously covered by private or public insurance.

For each method of contraception, failure rates for typical use were applied.[1] All pregnancies were categorized by intention as intended, mistimed or unwanted.[6, 7] An intended pregnancy was defined as a pregnancy in those women seeking pregnancy. We made the simplifying assumption that no women seeking pregnancy would experience a medical abortion. As mentioned above, our model spans a one-year time horizon for contraception uptake and coverage; however, the model captures outcomes that may occur beyond the one-year timeframe. As such, we defined a mistimed pregnancy as a woman getting pregnant who wanted to become pregnant in the future but not within the next year. An unwanted pregnancy was defined as a woman getting pregnant who had no intention of becoming pregnant in the future. The relative distribution of pregnancy type by age and marital status, as well as the rate of abortion by intention status, was pulled from a report by the Guttmacher Institute that combined several nationally representative data sources.[13] Rates of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy and stillbirth were drawn from nationally representative studies evaluating the probability of each event relative to maternal age.[19–21]

2.2. Costs Inputs

Annual costs of contraception were drawn from publicly available pricing tools, as well as a previously conducted cost-effectiveness study, and inflated to 2015 dollars.[3] Conservatively, these costs of contraception are retail prices and do not include cost sharing with the patient or negotiated discounts which might further lower costs to the employer. Costs of intended and unintended births were drawn from a study that analyzed average costs for delivery among employer-sponsored health insurance plans.[22] For all unintended births, we assumed that all associated costs would have been avoided if the pregnancy had not occurred. Costs of stillbirth, abortion, miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy were drawn from cost burden studies of pregnancy.[9, 23]

2.3. Total Costs

Total costs were calculated for three separate scenarios to account for the different ways that employers may cover contraception and pregnancy. In the first scenario (base-case), we included all contraception- and pregnancy-related costs for women in each arm of the study, regardless of whether they would be covered by the employer; we then varied the uptake frequencies for each contraceptive method to reflect the utilization patterns of women with and without insurance in the NSFG. This scenario most closely approximates the societal perspective, which includes all costs and consequences of an intervention regardless of who experiences them (e.g., public/private payers, employers, or employees, etc.). The second scenario estimated the difference in total costs for employers choosing to offer contraception coverage vs. no coverage, assuming that the employer’s insurance policy covered all pregnancy-related outcome costs, including the cost of abortion (for simplicity referred to as the ‘with abortion’ scenario). Under this scenario, employers choosing to provide contraception coverage would pay for contraception costs, as well as medical costs associated with the treatment of pregnancy outcomes. Those choosing not to offer contraception coverage would only pay for the cost of treating outcomes of pregnancy. Many employers who may be deciding whether or not to offer contraception coverage may also be unlikely to cover the cost of a medically-induced abortion. Therefore, we considered a third scenario where this cost was not covered by the employer. This final scenario (referred to as the ‘without abortion’ scenario) was structured the same as the ‘with abortion’ scenario, except that the costs of medically-induced abortions were excluded from the analyses. For all three scenarios, costs were translated into the commonly used per-member-per-month (PMPM) format that most payers use as the economic unit of measure. For this PMPM calculation we assumed that the health plan was 50% women.

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of our results under differing assumptions, we varied all cost and event parameters across a plausible range of values. The range for each parameter was drawn from the 95% confidence interval reported in the original source whenever possible. When a confidence interval was not reported, a range of ±10% and ±5% for cost and clinical parameters respectively was used. This process was conducted as a deterministic univariate sensitivity analysis with results reported in the form of a tornado diagram.[24] Finally, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed using a Monte Carlo simulation[24–26] in which all model parameters were varied simultaneously. In this analysis, the model was run using a value for each parameter drawn randomly from its assumed distribution. The process was repeated 100,000 times. Distributions were assigned based on the data from which the parameter estimates were derived. Beta distributions were assigned to probabilities that were constrained to fall between zero and one. Distributions of multiple probabilities that summed to one were modeled using a Dirichlet distribution.[27] All costs in the model were population averages and not individual estimates; thus, we modeled cost estimates using a normal distribution rather than a gamma distribution.

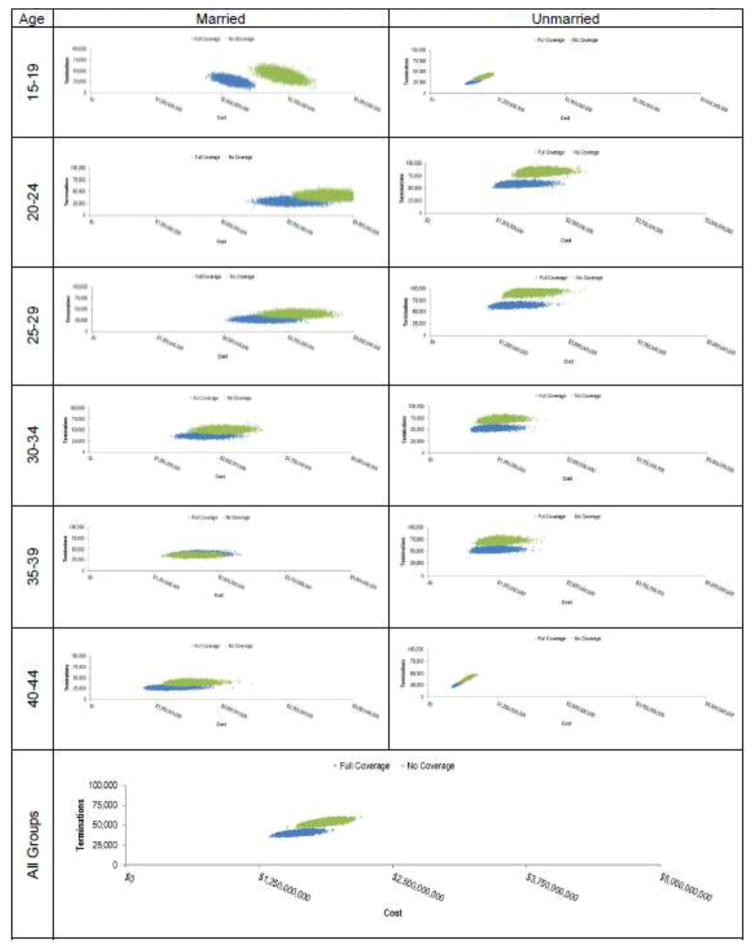

Additionally, we conducted a subgroup analysis where we simulated a population of 1,000,000 within each possible age group and marital status combination in our model. For each combination, the probabilistic sensitivity analysis was replicated with 10,000 model simulations to give a plausible distribution of results. We compared the results of each of these simulations to identify which groups may be particularly vulnerable to the loss of insurance status for contraceptives.

3. Results

Our base-case model showed that for one million women with the same age distribution as the US population, removing insurance coverage for contraceptives results in approximately 33,203 (95%CR: 22,358; 44,047) additional unintended pregnancies (by design, there was virtually no difference in the number of intended pregnancies). Notably, we found that insurance coverage was significantly associated with women’s choice of contraception method, with the use of oral contraceptives significantly lower in the uninsured group (−112,148 95% CR: −123,857; −100,439). As the rate of pregnancies increases due to uninsured women opting for less effective methods, there are additional pregnancy outcomes across all categories. For example, the increase in unintended pregnancies results in a subsequent increase in medical abortions of 13,460 per one million women (95% CR: 9,997; 16,923) (Table 3). In other words, there is an additional abortion for every 74 (95% CR: 59; 100) women denied access to private insurance contraceptive coverage in the US.

Table 3.

Results for Women 15–44yrs old (N=1,000,000)

| INSURED | UNINSURED | DELTA1 | DELTA (PMPM)1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contraceptive Use | ||||

| Oral contraceptive | 209,087 (198,144; 220,031) | 96,939 (91,824; 102,054) | −112,148 (−123,857; −100,439) | |

| IUD | 27,143 (25,619; 28,667) | 27,148 (25,619; 28,676) | 0,005 (−1,916; 1,926) | |

| Shot/Injectable | 12,181 (11,501; 12,861) | 23,507 (22,222; 24,792) | 11,326 (9,958; 12,694) | |

| Vaginal ring | 13,663 (12,907; 14,420) | 9,868 (9,279; 10,457) | −3,795 (−4,650; −2,940) | |

| Transdermal patch | 3,327 (3,144; 3,511) | 4,856 (4,531; 5,181) | 1,528 (1,178; 1,878) | |

| Implant | 1,791 (1,688; 1,894) | 1,791 (1,688; 1,895) | 0 (−126; 127) | |

| Other methods | 2,096 (1,974; 2,219) | 2,478 (2,321; 2,636) | 382 (209; 554) | |

| No method | 105,523 (96,590; 114,456) | 144,711 (134,277; 155,144) | 39,187 (30,152; 48,223) | |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Pregnancies | 133,141 (122,799; 143,482) | 166,343 (153,916; 178,771) | 33,203 (22,358; 44,047) | |

| Births Intended | 26,702 (21,638; 31,765) | 26,707 (21,633; 31,781) | 0,005 (−1,894; 1,904) | |

| Births Unintended | 48,897 (45,730; 52,064) | 65,375 (61,003; 69,747) | 16,478 (12,269; 20,687) | |

| Mistimed | 31,307 (28,936; 33,678) | 42,105 (38,868; 45,342) | 10,798 (8,055; 13,541) | |

| Unwanted | 17,590 (16,181; 18,999) | 23,270 (21,356; 25,184) | 5,680 (4,145; 7,215) | |

| Abortion | 40,222 (37,533; 42,910) | 53,682 (50,002; 57,361) | 13,460 (9,997; 16,923) | |

| Miscarriage | 15,865 (14,238; 17,493) | 18,808 (17,023; 20,593) | 2,943 (1,696; 4,189) | |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 885 (812; 958) | 1,075 (991; 1,160) | 190 (119; 261) | |

| Stillbirth | 323 (291; 354) | 385 (350; 420) | 63 (37; 88) | |

| Contraceptive Cost | ||||

| Oral contraceptive | 108.1 (102.4; 113.7) | 50.1 (47.5; 52.8) | 58.0(51.9; 64.0) | 2.42 (2.16; 2.67) |

| IUD | 21.3 (20.1; 22.5) | 21.3 (20.1; 22.5) | 0.0 (−1.5; 1.5) | 0.00 (−0.06; 0.06) |

| Shot/Injectable | 4.9 (4.6; 5.1) | 9.4 (8.9; 9.9) | −4.5 (−5.0; −4.0) | −0.19 (−0.21; −0.17) |

| Vaginal ring | 21.9 (20.7; 23.1) | 15.8 (14.9; 16.7) | 6.1 (4.7; 7.4) | 0.25 (0.20; 0.31) |

| Transdermal patch | 2.5 (2.3; 2.6) | 3.6 (3.4; 3.9) | −1.1 (−1.4; −0.9) | −0.05 (−0.06; −0.04) |

| Implant | 1.7 (1.6; 1.8) | 1.7 (1.6; 1.8) | −0.3 (−0.1; 0.1) | 0.00 (−0.01; 0.01) |

| TOTAL | 160.4 (152.0; 168.8) | 102.0 (96.6; 107.4) | 58.4 (48.8; 68.0) | 2.43 (2.03; 2.83) |

| Outcome Cost | ||||

| Births Intended | 513.8 (416.3; 611.2) | 513.9 (416.2; 611.5) | −0.1(−36.6; 36.4) | 0.00 (−1.53; 1.52) |

| Births Unintended | 878.1 (821.2; 935.0) | 1,174.0 (1,095.5; 1,252.5) | −295.9 (−371.5; −220,.3) | −12.33 (−15.48; −9.18) |

| Abortion | 30.6 (28.6; 32.7) | 40.9 (38.1; 43.7) | −10.3 (−12.9; −7.6) | −0.43 (−0.54; −0.32) |

| Miscarriage | 14.9 (13.4; 16.5) | 17.7 (16.0; 19.4) | −2.8 (−3.9; −1.6) | −0.12 (−0.16; −0.07) |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 4.2 (3.9; 4.5) | 5.1 (4.7; 5.5) | −0.9 (−1,2; −0.6) | −0.04 (−0.05; −0.02) |

| Stillbirth | 1.9 (1.7; 2.1) | 2.3 (2.1; 2.5) | −0.4 (−0.5; −0.2) | −0.02 (−0.02; −0.01) |

| TOTAL | 1,443.5 (1,312.0; 1,575.1) | 1,753.9 (1,604.6; 1,903.1) | −310.3 (−425.6; −195.0) | −12.93 (−17.73; −8.12) |

| GRAND TOTAL | 1,603.9 (1,467.9; 1,740.0) | 1,855.9 (1,703.3; 2,008.4) | −251.9 (−376.2; −127.7) | −10.50 (−15.67; −5.32) |

| EMPLOYER TOTAL | CONTRACEPTION COVERED | CONTRACEPTION NOT COVERED | ||

| With Abortion | 1,603.9 (1,464.0; 1,743.8) | 1,753.9 (1,604.6; 1,903.1) | −149.9 (−140.6; −159.3) | −6.25 (−5.86; −6.64) |

| Without Abortion | 1,573.3 (1,435.4; 1,711.2) | 1,713.0 (1,566.5; 1,859.4) | −139.7 (−131.1; −148.3) | −5.82 (−5.46; −6.18) |

Positive delta value for contraceptive use indicates that more women choose that method in the no insurance arm, positive delta value in outcomes indicates that more women have the event in the uninsured arm, negative values for costs indicates greater cost for uninsured arm

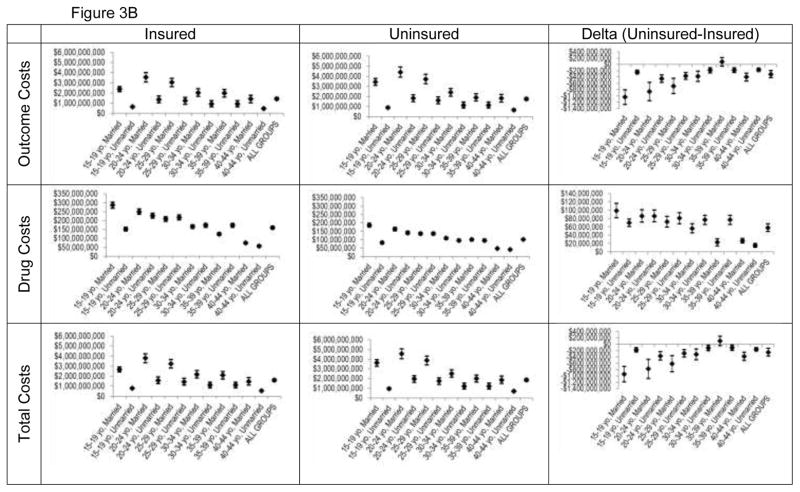

In our base-case model, removal of coverage for contraception resulted in a statistically significant increase of $251,929,900 per 1,000,000 women (95%CR: $127,683,800; $376,176,300) or $10.50 PMPM (95%CR: $5.32 PMPM; $15.67 PMPM) in healthcare expenditures. For the ‘with abortion’ scenario, no insurance coverage resulted in an additional $149,931,300 per 1,000,000 women (95%CR: $140,601,000; $159,261,700) or $6.25 PMPM (95%CR: $5.86 PMPM; $6.64 PMPM). For the ‘without abortion’ scenario, conservatively assuming no coverage of abortions, this increase in costs persisted with an additional $139,676,500 per 1,000,000 women (95%CR: $131,101,600; $148,251,500) or $5.82 PMPM (95%CR: $5.46 PMPM; $6.18 PMPM). Thus, we project that employers choosing not to offer contraception coverage to their employees will experience significantly higher expenditures, a greater number of employees experiencing unintended pregnancies and subsequent medically-induced abortions, even when excluding insurance costs associated with medical abortions.

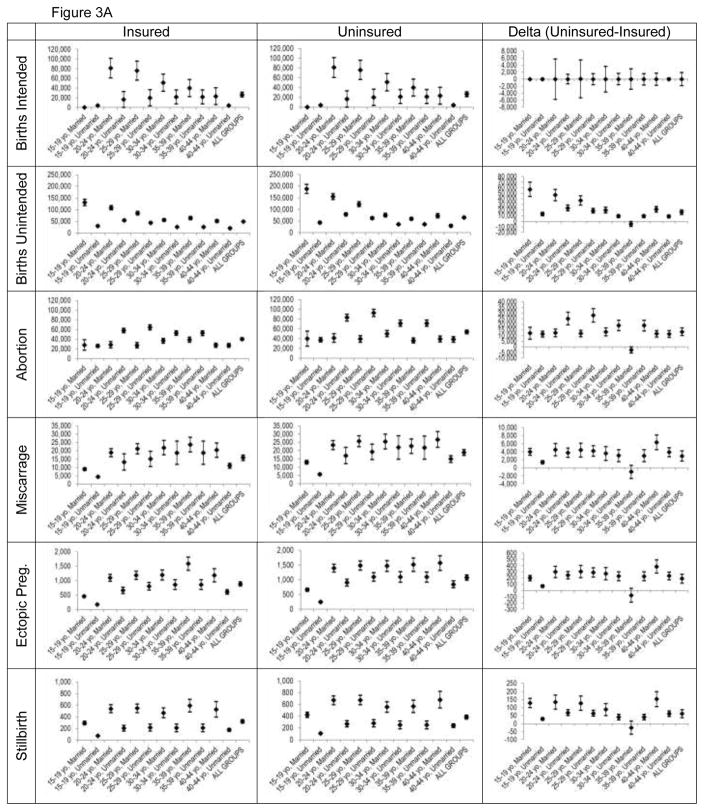

We identified several trends through our subgroup analysis. First, there was a greater difference in outcomes and costs for both younger (under 30) and older (above 40) women when modeled to experience loss of insurance coverage. The effect of no insurance was greatest on unmarried women 20–29 years old. When unmarried women 20–24 years old and 25–29 years old lack contraceptive coverage, there are an additional 25,228 (95%CR: 19,752; 30,704) and 28,054 (95%CR: 22,035; 34,072) abortions per 1,000,000 women in each age group, respectively. Stated another way, there is one additional abortion for every 39 and 35 women in these groups who lose health insurance. For married women who are 35–39, there is virtually no difference in number of pregnancies and subsequent abortions compared to unmarried women, perhaps due in part to fairly consistent levels of contraception use among women in this age category regardless of insurance or marital status, as well as lower rates of women at risk for pregnancy in this age category in general.

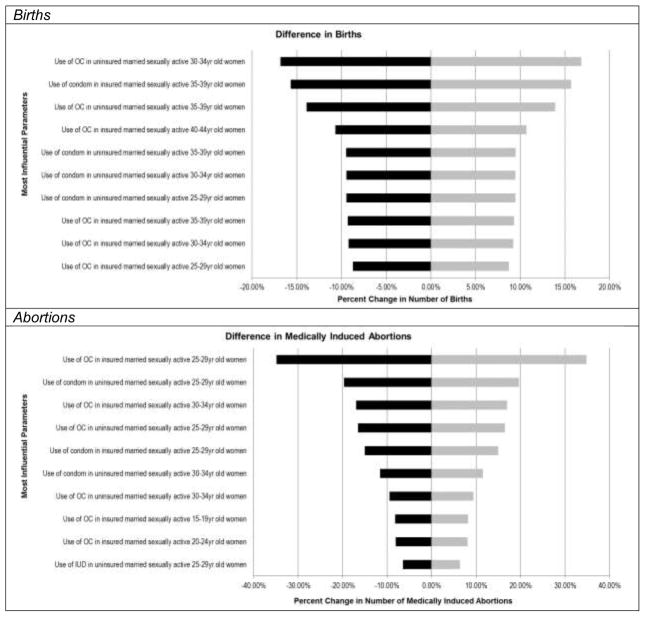

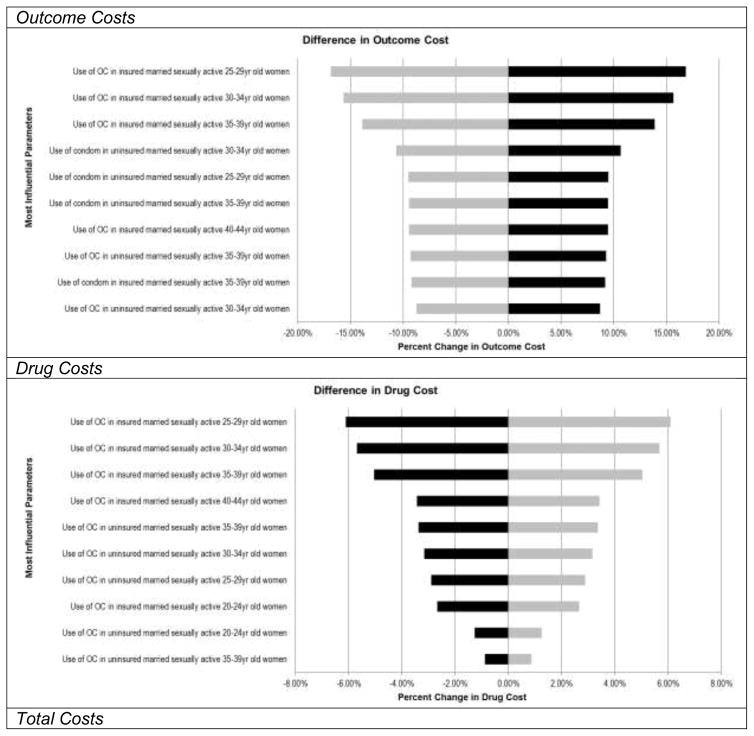

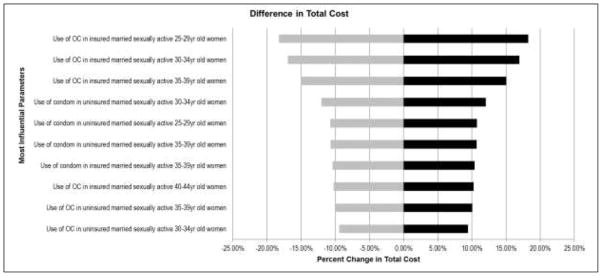

Our one-way sensitivity analysis showed that our model was relatively robust to assumptions about our input parameters (Appendix Tables 1A and 1B). For the endpoints of difference in number of live births and medically induced abortions, as well as outcome costs and total costs, the most influential parameters were the proportion of sexually active women expected to use no method of contraception. For the costs of contraception coverage, the most influential factors were the proportion of women expected to use oral contraception across different age groups.

4. Conclusions

Our model shows that removing private health insurance coverage for contraceptive methods results in more unintended pregnancies, more medically induced abortions, and greater total costs from the societal and employer perspectives, regardless of whether medically-induced abortion was modeled as a covered insurance benefit. Research has shown that women are price-sensitive to out-of-pocket costs for contraceptives.[8] Eliminating private health insurance coverage, and thus, potentially increasing the out-of-pocket cost burden for women would likely reduce contraceptive use among these women and lead to more unintended pregnancies, terminations, and associated social and individual costs. Particularly for low-income women, the repercussions of lack of insurance coverage for contraception could play a significant role in reinforcing the cycle of poverty and economic stagnation that often accompanies unintended pregnancy.

Our findings are particularly compelling given the recent political discourse related to private insurance coverage and employer-sponsored coverage of contraceptives in the U.S. market. While private health insurance plans are required by the ACA to cover contraceptives at no cost to the beneficiary, the Guttmacher Institute reports that some plans still do not provide coverage for all contraceptive methods.[28] Some state and federal policies provide exemptions for religiously-affiliated private health insurers.[28] The ACA also required closely held employers to provide insurance coverage, including coverage of contraception, to employees. However, the highly publicized 2014 U.S. Supreme Court case of Burwell vs. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. established an exemption from mandated coverage for closely held employers that provide health insurance to their employees, citing the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act.[29]

According to recent studies, closely held companies employ roughly 52% of the American workforce.[30, 31] While the actual number of employers and insurers that will claim exemptions from contraception coverage is not yet known, our model suggests that the lack of insurance coverage that might result from exemptions could present a significant public health problem if other avenues for affordable access to contraceptives are not made available. Evidence suggests that effective contraceptive utilization increases when insurance coverage is introduced.[8] A study conducted by Kaiser Permanente of Northern California found that when cost-sharing for contraception was eliminated, demand for and utilization of birth control methods increased; the study findings estimated that increased utilization also decreased the risk of unintended pregnancy by 82%,[32] and thus, terminations.

Our findings demonstrate that the increased utilization achieved by making contraception available through employer-based insurance plans at no cost-sharing for women of childbearing years may be a highly successful strategy in reducing unwanted and mistimed pregnancies, terminations, and associated costs. From the perspective of the health plan, coverage of contraception reduces costs for all members. From the employer perspective, coverage of contraception may avoid additional expenses incurred due to unintended pregnancies among employees, such as economic losses associated with employee absenteeism, decreased productivity, higher employee replacement costs, maternity leave, sick leave, and loss of employees due to pregnancy. Importantly, recent caveats of the ACA (e.g., exempting employers from the coverage requirements based on religious determination) may limit a woman’s ability to receive contraception at no-cost (e.g., requiring a co-pay or deductible). Complementing patient-level research showing large societal and individual benefits of no-cost contraception coverage,[8, 32] our findings suggest that no-cost contraception coverage would be highly valuable from the employer and private payer perspectives, as well.

Our model has several notable limitations. First our analysis is a simulation of the implications of the loss of insurance coverage on contraception choices rather than an analysis of real-world data. Secondly, our estimates for choice of contraceptive method were pulled from the NSFG, which does not have information on costs of contraceptive and non-contraceptive medical expenses by type of insurance coverage. To assess contraception method mix, we analyzed data from the 2006–2010 NSFG. Future studies might consider using the more recently available 2011–2013 NSFG data, which may reflect more current contraception utilization patterns. However, we chose to use the earlier dataset to allow for corroboration of estimates and ensure the use of data analytic methodologies consistent with prior NSFG publications. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the NSFG data source limits our ability to make assumptions about how women in the study might switch their birth control choices if they were to experience cost-sharing vs. no cost-sharing for contraception based on changes in employer insurance offerings. For example, uninsured women in our model had higher use of long-acting contraceptives, which is in contrast to expectations based on the literature.[33] Presumably, some of these women may have received coverage for their long-acting contraception during a previous time period when their insurance situation was different. As the choice for use of oral contraception was more proximal to the NSFG survey, the level of usage was predictably lower. Finally, there may potentially be a difference between the choice of contraceptive methods among women who have no insurance at all and women that use coverage only for non-contraceptive medical expenses. However, the use of the NSFG provides a nationally representative analysis of contraception use by insurance status, allowing for greater insight into demographic differences than has previously been possible.

Effects of individual-level characteristics, such as sexual activity and marital status, were influential on the model outcomes, suggesting that employee demographics and population-level characteristics may influence the costs and consequences of contraception coverage (or lack of coverage). These characteristics should be taken into consideration when developing policies related to contraception coverage in the future. Additionally, we found that private insurance coverage of contraception is cost-effective from the employer and private health plan perspectives. Employers and health plans that are deciding whether or not to offer coverage at no cost-sharing to their employees should consider the full impact that this decision could have on their bottom line, on the physical and economic health of their employees, and on public health outcomes.

Figure 2.

Probabilistic Sensitivity Results: Medically-Induced Terminations and Costs by Insurance Coverage

Figure 3.

Figure 3A: Population Subgroup Event Results by Age, Marital Status and Insurance Coverage

Figure 3B: Population Subgroup Cost Results by Age, Marital Status and Insurance Coverage

Appendix Figure 1A.

One-Way Sensitivity Analysis for Event Endpoints

Appendix Figure 1B.

One-Way Sensitivity Analysis for Event Endpoints

Table 1B.

Base-Case Assumptions and Ranges for Sensitivity Analysis ($USD)

| Variable | Value | Range | Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Costs | ||||

| Live Births | ||||

| Intended Pregnancy | 19,241 | 17,317; 21,165 | Normal | [22] |

| Unwanted Pregnancy | 17,958 | 16,162; 19,754 | Normal | [22] |

| Mistimed Pregnancy | 17,958 | 16,162; 19,754 | Normal | [22] |

| Medically induced abortion | 762 | 686; 838 | Normal | [9] |

| Miscarriage | 941 | 846; 1,035 | Normal | [9] |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 4,740 | 4,266; 5,214 | Normal | [9] |

| Stillbirth/other neonatal death | 5,977 | 5,379; 6,575 | Normal | [23] |

| Treatment Costs | ||||

| Office Visit (CPT 99213) | 73 | 66; 80 | Normal | [35] |

| IUD Insertion (CPT 58300) | 71 | 64;78 | Normal | [35] |

| Implant Insertion (CPT 11981) | 143 | 129; 158 | Normal | [35] |

| Mirena® | 697 | 627; 767 | Normal | [3] |

| Paragard® | 588 | 529; 646 | Normal | [3] |

| Implanon® | 746 | 671; 821 | Normal | [3] |

| Contraceptive Injection (3 month) | 100 | 90; 110 | Normal | [36] |

| Trandermal Patch (1 month) | 746 | 672; 821 | Normal | [36] |

| Vaginal Ring (1 month) | 127 | 115; ,140 | Normal | [36] |

| Oral Contraceptive (1 month) | 37 | 33; 41 | Normal | [36] |

Table 2.

Base-Case Pregnancy Intendedness and Outcomes

| Group | INTENDEDNESS[13] | PREGNANCY OUTCOME (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | % | Birth[13] | Miscarriage[37] | Ectopic Preg.[38] | Stillbirth[21] | Abortion[13] | ||

| MARRIED | 15–19 | Intended | 43 | 90 | 9.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 54 | 82 | 5.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 13 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 2.9 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 94 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 20–24 | Intended | 57 | 90 | 9.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 35 | 75 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 17 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 7.8 | 62 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 31 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 25–29 | Intended | 69 | 86 | 12.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 22 | 70 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 21 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 9 | 65 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 26. | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 30–34 | Intended | 74 | 80 | 18.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 12 | 72 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 17 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 14 | 38 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 51 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 35–39 | Intended | 74 | 80 | 18 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 12 | 72 | 12 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 14. | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 14 | 38 | 12 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 48. | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 40–44 | Intended | 74 | 80 | 18 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 12 | 72 | 16 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 11 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 14 | 38 | 16 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 45 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| UNMARRIED | 15–19 | Intended | 16 | 77 | 22 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 60 | 54 | 5.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 41 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 24 | 43 | 5.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 51 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 20–24 | Intended | 27 | 77 | 22 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 47 | 46 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 456 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 25 | 42 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 50. | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 25–29 | Intended | 37 | 78 | 21 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 30 | 32 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 59 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 33 | 41 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 50 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 30–34 | Intended | 37 | 667 | 32 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 26 | 33 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 57 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 37 | 27 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 62 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 35–39 | Intended | 37 | 67 | 32 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 26 | 33 | 12 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 54 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 37 | 27 | 12 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 59 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 40–44 | Intended | 37 | 67 | 32 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 26 | 33 | 16 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 50 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 37 | 27 | 16 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 55 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| All Ages | Intended | 47 | 78 | 21 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mistimed | 31 | 55 | 9.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 35 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Unwanted | 23 | 40 | 9.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 50 | ||

IMPLICATIONS.

Insurance coverage was found to be significantly affect associated with women’s choice of contraceptive method in a large nationally-representative sample. Using a decision model to extrapolate to pregnancy outcomes, we found a large and statistically significant difference in unintended pregnancy and terminations. Denying women contraception coverage may have significant consequences for pregnancy outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source:

Support for this research was provided in part by an infrastructure grant for population research from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health P2C HD047879 (JT).

Footnotes

Conflicts:

W Canestaro has served as a paid consultant for the National Pharmaceutical Council, Genentech and AstraZeneca.

E Vodicka: none.

D Downing: none.

J Trussell serves on advisory boards for Merck and Teva.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimes DA. The safety of oral contraceptives: epidemiologic insights from the first 30 years. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1992;166:1950–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91394-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J. Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. 2009;79:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson R, Collins SR. Women at risk: why increasing numbers of women are failing to get the health care they need and how the Affordable Care Act will help. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey of 2010. Issue brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2011;3:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulligan K. Contraception Use, Abortions, and Births: The Effect of Insurance Mandates. Demography. 2015;52:1195–217. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. American journal of public health. 2014;104:S43–S8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84:478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonfield A, Kost K, Gold RB, Finer LB. The public costs of births resulting from unintended pregnancies: national and state-level estimates. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43:94–102. doi: 10.1363/4309411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, Finer LB. Return on Investment: A Fuller Assessment of the Benefits and Cost Savings of the US Publicly Funded Family Planning Program. Milbank Quarterly. 2014;92:696–749. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burlone S, Edelman Ab, Caughey AB, Caughey Ab, Trussell J, Dantas S, Rodriguez MI. Extending contraceptive coverage under the Affordable Care Act saves public funds. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006–2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. National health statistics reports. 2012;60:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zolna M, Lindberg LD. Unintended pregnancy: Incidence and outcomes among young adult unmarried women in the United States, 2001 and 2008. Alan Guttmacher Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summary File 1. U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summary File 1. U.S. Census Bureau; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau USC. Table 1A. Marital Status of People 15 Years and Over by Age, Sex, Personal Earnings, Race, and Hispanic Origin. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS data brief. 2014;173:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubacher D, Spector H, Monteith C, Chen PL, Hart C. Rationale and enrollment results for a partially randomized patient preference trial to compare continuation rates of short-acting and long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2015;91:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammon Avalos L, Galindo C, Li DK. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2012;94:417–23. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2013. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldenstrom U, Cnattingius S, Norman M, Schytt E. Advanced Maternal Age and Stillbirth Risk in Nulliparous and Parous Women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;126:355–62. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieguez G, Pyenson BS, Law AW, Lynen R, Trussell J. The cost of unintended pregnancies for employer-sponsored health insurance plans. American health & drug benefits. 2015;8:83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold K, Sen A, Xu X. Hospital Costs Associated with Stillbirth Delivery. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;17:1835–41. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1203-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briggs AH, Weinstein MC, Fenwick EAL, Karnon J, Sculpher MJ, Paltiel AD. Model Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Analysis: A Report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force Working Group–6. Medical Decision Making. 2012;32:722–32. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12458348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Critchfield GC, Willard KE, Connelly DP. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis methods for general decision models. Comput Biomed Res. 1986;19:254–65. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(86)90020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doubilet P, Begg CB, Weinstein MC, Braun P, McNeil BJ. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation. A practical approach. Med Decis Making. 1985;5:157–77. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8500500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myerson RB. Probability Models for Economic Decisions. Thomson/Brooke/Cole; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives. State Policies in Brief. Guttmacher Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gostin LO. The ACA’s Contraceptive Mandate: Religious Freedom, Women’s Health, and Corporate Personhood. Jama. 2014;312:785–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagar V, Petroni K, Wolfenzon D. Governance problems in closely held corporations. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 2011;46:943–66. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagar V, Petroni K, Wolfenzon D. Ownership and performance in close corporations: a natural experiment in exogenous ownership structure. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postlethwaite D, Trussell J, Zoolakis A, Shabear R, Petitti D. A comparison of contraceptive procurement pre-and post-benefit change. Contraception. 2007;76:360–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenberg D, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Cost as a Barrier to Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive (LARC) Use in Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 52:S59–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States Department of Commerce. Bureau of the C. Census of Population and Housing, 2010 [United States]: National Summary File of Redistricting Data. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor] 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Services CfMaM, editor. RVU15A. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.GoodRx.

- 37.Andersen A-MN, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, Olsen J, Melbye M. Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ. 2000;320:1708–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prevention CfDCa. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2013. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]