Abstract

Host and virus interactions at the post-transcriptional level are critical for infection but remain poorly understood. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a prevalent herpesvirus family member that causes severe complications in immunocompromised patients and newborns. Here, we perform comprehensive transcriptome-wide analyses revealing that HCMV infection results in widespread alternative splicing (AS), shorter 3′-untranslated regions (3′UTRs) and polyA tail lengthening in host genes. The host RNA binding protein cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1 (CPEB1) is highly induced upon infection and ectopic expression of CPEB1 in non-infected cells recapitulates infection-related post-transcriptional changes. CPEB1 is also required for polyA-tail lengthening of viral RNAs important for productive infection. Strikingly, depletion of CPEB1 reverses infection-related cytopathology and post-transcriptional changes, and decreases productive HCMV titers. Host RNA processing is also altered in herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) infected cells, indicating a common theme among herpesvirus infections. Our work is a starting point for therapeutic targeting of host RNA binding proteins in herpesvirus infections.

Introduction

Human herpesvirus infections are highly prevalent, significantly impacting global health. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a herpesvirus family member, infects nearly 100% of individuals in the United States by adulthood 1 and >5,000 infants born with HCMV infection each year suffer pervasive developmental deficits. Infection can cause severe neurological defects in newborns and serious disease in immunocompromised individuals 2–4 and has also been associated with glioblastoma and atherosclerosis 5–8. Therapeutic options are limited, and there is currently no vaccine to prevent infection. HCMV infects a variety of cell types, but the interaction and response between viral and host transcriptomes remains largely unclear. In early stages of infection for herpesviruses, the cellular environment must be poised for viral replication, and for some herpesviruses, a complete shutdown of host transcription and protein synthesis occurs 9–11. This is not the case for HCMV; there is not an overall decrease in host mRNA levels during infection 12. An efficient avenue for rapid alteration of the host cellular environment is to modulate cellular RNA processing. Host RNA-regulatory factors capable of such sweeping changes may be responsible for progressive HCMV lytic infection, and although viral gene expression and splicing have been studied 13–14, the changes in host RNA processing during HCMV infection are largely unexplored.

Nuclear RNA processing functions such as alternative splicing (AS) and alternative cleavage and polyadenylation (APA) are responsible for generating the functional mammalian transcriptome necessary for tissue development and maintenance 15–17. The importance of proper control of AS and APA is highlighted by a number of human diseases that occur due to defects in these processes 17–20. For example, global AS defects that lead to disease manifestations are known for myotonic dystrophy (DM) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) 15, and global changes in APA are also observed in DM, oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) 15,17,21. In the cytoplasm, the cytoplasmic polyadenylation (cPA) machinery targets RNAs that contain a short polyA tail 22. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1 (CPEB1) recognizes cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements (CPEs) within RNA substrates that leads to the recruitment of polyA polymerase (PAP) GLD2 to elongate the polyA tail 22. PolyA tail length changes alter translation of certain transcripts and increased PAP activity is linked to poor prognosis in some cancers 23. The recent availability of techniques such as PAL-seq 24 and TAIL-seq 25 has enabled genome-wide measurements of polyA tail lengths. However, transcriptome-wide changes in polyA tail lengths have not been determined in human disease and viral infections.

RNA binding proteins (RBPs) are responsible for regulating RNA processing and shaping the RNA landscapes in cells to determine cellular fates in differentiation and disease. Families of RBPs such as Muscleblind-like (MBNL), NOVA, RBFOX, and HNRNPs have been shown to control both AS and APA 17,19,26–29. However, the involvement of RBPs in the modulation of host or viral transcriptomes during virus infections remains poorly understood. In this study, transcriptome-wide analyses reveal that HCMV infection leads to widespread host and viral gene expression and RNA processing changes. Surprisingly, we discovered that the RBP CPEB1 is upregulated during HCMV infection. Exogenous expression of CPEB1 in the absence of HCMV infection recapitulated infection-related host AS and APA patterns. Additionally, depletion of CPEB1 during HCMV infection led to the reversal of a large fraction of infection related host AS, APA, and cPA changes. Strikingly, reduction of CPEB1 led to shortened viral polyA tail lengths within CPEB1-bound substrates, decreased protein levels of late viral proteins, and reduced productive viral titers. Our results demonstrate that CPEB1 is required for modulating host and viral transcripts necessary for full-blown lytic HCMV infection.

Results

Host RNA processing is extensively altered in HCMV infection

To assess mRNA expression patterns for host and HCMV genes, we generated polyA+ RNA-seq libraries from primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs), human aortic endothelial cells (ECs), and human embryonic stem (ES) cell derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) at both 48 and 96 hours post-infection (hpi) with the clinical HCMV isolate TB40E (multiplicity of infection or MOI of 5; Supplementary Fig. 1a). These are commonly infected cell types that support varying degrees of viral infection 30. Indeed, while viral gene expression correlated by infection time-points in HFF, EC, and NPC cells (Supplementary Fig. 1b, based on annotated HCMV ORFs), marked expression changes in viral genes were observed in HFFs and ECs at 96 hpi, but not in the NPCs (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d, Supplementary Data Set 1). This is consistent with previous observations of non-progressive infection in this NPC model 30. Nonetheless, HCMV mRNA expression was similar in the three cell lines at early times during the infection (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

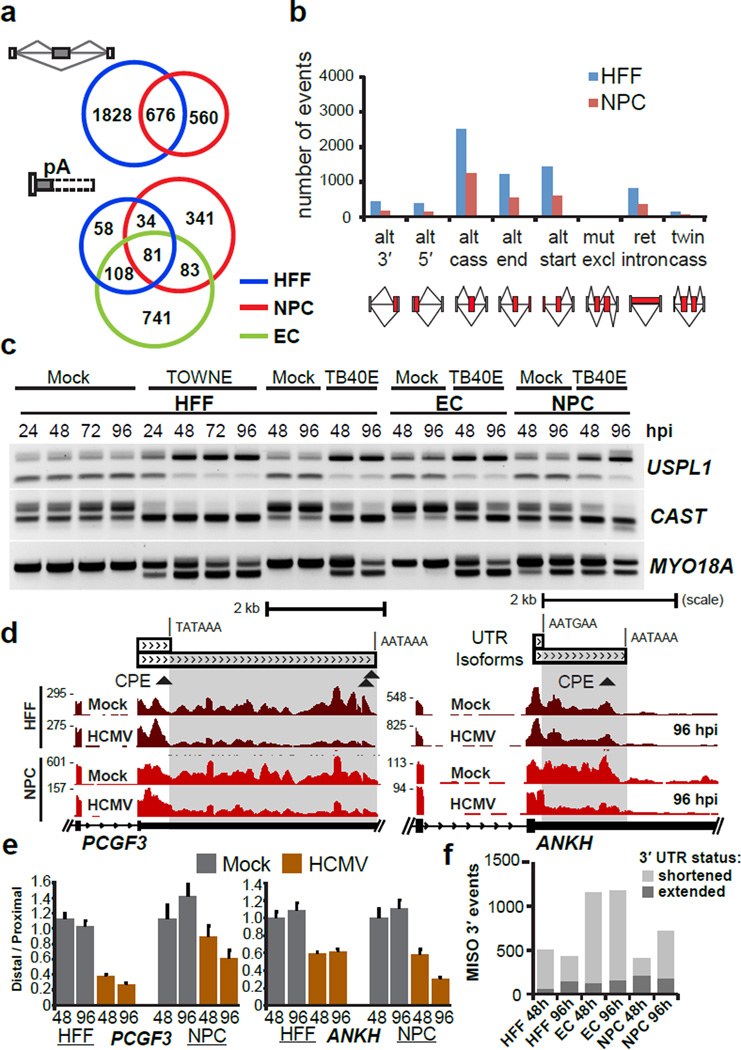

Next, we evaluated alterations in host cell RNA processing pathways as a result of HCMV infection. Using splicing-sensitive Affymetrix microarrays, we found >2,000 significantly altered host RNA splicing events (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Data Set 2) in HCMV-infected HFFs and NPCs 28. Although NPCs exhibited fewer AS changes, half of the NPC alternative cassette events overlapped with changes in HFFs (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Data Set 2), demonstrating that a similar AS program is established by HCMV infection. To study APA changes in host genes, we used the MISO algorithm 27 to survey tandem 3′UTR events and alternative 3′ terminal exons detected in the RNA-seq data. Interestingly, the majority of these events resulted in shortened 3′UTRs post-infection in the three cell types (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data Set 3). We validated both AS (exons within UPSL1, CAST and MYO18A genes in Fig. 1c) and APA (3’UTRs within PCGF3, ANKH and MARCH6 genes in Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Fig. 2,b) events that were specific to either the infected NPCs or HFFs and ECs. For APA, affected transcripts were generally shortened (Fig. 1f) by 1 to 5 kb in length by 96 hpi (Supplementary Fig. 2c). We also generated RNA-seq data from HFFs infected with Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2) at 8 hpi and analyzed APA using the MISO algorithm (Supplementary Data Set 3e). We found 278 altered events (173 or ~ 62% 3′UTR shortening events, Supplementary Fig. 2d) out of which 51 events (18%) were also common with HCMV APA events (Supplementary Fig. 2d, right) including ANKH and PCGF3 (Supplementary Fig. 2e,f). We also found AS changes in genes such as PICALM (Supplementary Fig. 2g). However, we did not find APA changes in T-cells infected with the RNA virus human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1, Supplementary Fig. 2d). We conclude that AS and APA in host RNA transcripts are dramatically altered by herpesvirus family members HSV-2 and HCMV.

Figure 1. Host RNA processing patterns are altered during HCMV infection.

(a) Overlap of alternative cassette exon splicing events (top) and alternative polyadenylation (APA) events (bottom) between infected HFFs, NPCs and ECs (n=1 for each condition for each cell type; MOI 5). (b) Numbers and type of infection-altered splicing events in NPCs and HFFs, detected by splicing-sensitive microarrays of Towne-infected HFFs at 72 hpi and TB40E–infected NPCs at 96 hpi. Abbreviations used are: alt, alternative; cass, cassette; mut excl, mutually exclusive; ret, retained. (c) RT-PCR validation of alternative cassette events in mock and HCMV infected HFFs, NPCs, and ECs (3/3 selected events were validated). (d) RNA-seq coverage of PCGF3 and ANKH showing 3′UTR shortening in HCMV infected NPCs (96 hpi) and HFFs. Canonical predicted canonical CPEB1 recognition sites (CPE; specifically, (U)UUUUAU or UUUUAA(U)) are indicated by triangles below the 3’UTRs. (e) qRT-PCR validation of decreased distal 3′UTR usage in PCGF3 and ANKH mRNA transcripts (4/5 targets selected were validated). Error bars = mean +/− standard deviation; n=3 qRT-PCR reaction replicates (f) Identification of altered 3′UTR isoform usage determined by the MISO algorithm in the indicated HCMV viral infection conditions.

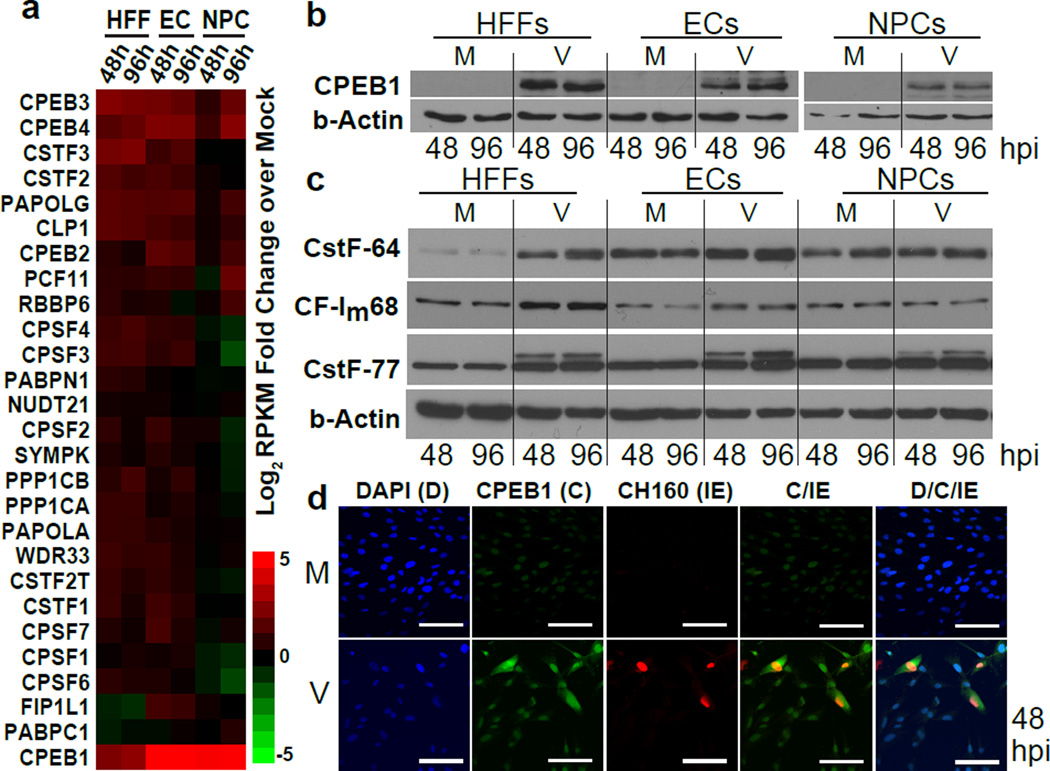

CPEB1 is consistently upregulated during HCMV infection

The shortening of 3’UTRs between the different cell types implied the involvement of one or more common RNA regulatory factors. We evaluated the mRNA abundance (by RNA-seq) for genes during HMCV infection. (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Data Set 4), focusing on host RBPs known to regulate APA (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Data Set 4). Unexpectedly, the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1 (CPEB1) emerged as the most dramatically and consistently upregulated RBP in all cell types at mRNA (6-fold in HFFs, and over 30-fold in both ECs and NPCs by 96 hpi) and protein levels during HCMV infection (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3d–f, Supplementary Data Set 3e). Protein levels of most of the known mediators of 3′ end formation (including the CSTF-64, CSTF-77, CF-Im68, CPSF160, and CPSF100 proteins), HNRNP family members (HNRNPH, HNRNPM, and HNRNPU) and other CPEB family members were not consistently altered across cell types (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 3f and 4a–c). Curiously, there was an induction of a longer CSTF-77 isoform in all three cell types (Fig. 2c), but the longer isoform is not associated with 3′UTR shortening according to a previous report 31. We observed upregulation of the CSTF-64 protein in infected HFFs (Fig. 2c), but it did not affect candidate 3’UTR shortening events in HFFs (Supplementary Fig. 4d,e). To demonstrate specificity for HCMV infection, UV-inactivated HCMV or interferon-gamma (IFN-g) neither induced CPEB1 upregulation (Supplementary Fig. 4f) nor caused HCMV-related AS in the SPAG9 and ITGA6 genes (Supplementary Fig. 4g). At the subcellular level, CPEB1 upregulation was observed in the infected cells (MOI 0.5) marked with the major immediate early viral proteins (IE1 and IE2; CH160 antibody) at 48 hpi by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2d), and CPEB1 was present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of HCMV-infected cells. Thus, we conclude that CPEB1 is consistently and robustly upregulated upon infection in all three cell types.

Figure 2. RNA binding protein CPEB1 is upregulated in HCMV-infected HFFs, ECs, and NPCs.

(a) Heatmap of fold-change (log2) for host 3′ end processing factors calculated from ratios of RPKMs (normalized to mock, MOI 5). Upregulated = red, and downregulated = green. (b) Immunoblot analysis of CPEB1 upregulation upon HCMV TB40E infection (V, MOI 5) compared to mock uninfected (M) conditions across three cell types. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 11. (c) Immunoblot analysis of host core 3′ end processing factors. β-actin was used as a loading control. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 11. (d) Immunofluorescence of HCMV immediate-early (IE) protein CH160 (red) and CPEB1 (C, green) with DAPI (D) in HFFs at 48 hpi (MOI 0.5). Scale bars are 100 µm.

CPEB1 expression causes changes reminiscent of HCMV infection

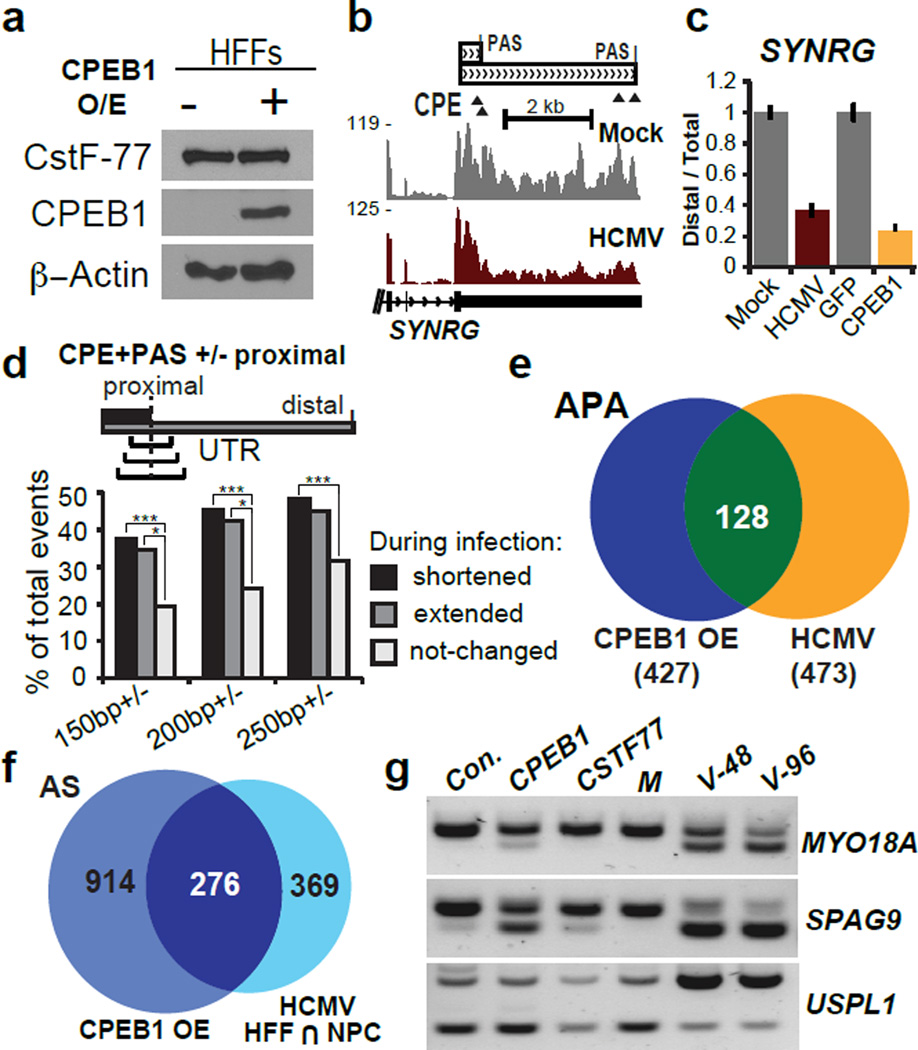

To evaluate whether CPEB1 is indeed responsible for the RNA processing changes observed during HCMV infection, we ectopically expressed the full-length isoform of CPEB1 in non-infected HFFs (Fig. 3a) and subjected the cells to RNA-seq analysis. Strikingly, CPEB1 overexpression (OE) in uninfected cells caused a significant shift towards utilization of proximal polyA sites in genes found to be affected during infection (SYNRG in Fig. 3b,c). Consensus UUUUUAU sequences (CPE) in proximity to a polyadenylation signal (PAS) are known to recruit CPEB1 to 3′UTR regions 22. Although we do not yet know whether these sequence elements alone are sufficient for the recently proposed role of CPEB1 in RNA processing 32, enrichment of these elements was reported for affected transcripts in regions surrounding alternative cleavage sites. Indeed, we found that ~50% of isoforms that shortened during infection contained CPE-PAS co-occurrences surrounding the proximal 3′ end (250 nt), two-fold above the isoforms that remained unchanged during infection (Fig. 3d). Additionally, genome-wide comparisons showed that 27% (128/473, Fig. 3e, Supplementary Data Set 3) of the APA changes (by RNA-seq) and 43% (276/645, Fig. 3f and Supplementary Data Set 5) of the AS changes (by splicing sensitive microarrays) that were consistent between infected HFFs and NPCs also occured in CPEB1 OE HFFs without infection. Notably, CPEB1 OE, but not CSTF-77 OE, caused similar AS changes in MYO18A and SPAG9 that resembled changes upon HCMV infection, but not in USPL1 (Fig. 3g). Therefore, we conclude that CPEB1 is responsible for a large fraction of the RNA processing changes during HCMV infection in HFFs.

Figure 3. Exogenous CPEB1 expression causes RNA processing changes reminiscent of HCMV infection.

(a) Immunoblot of lentivirus-mediated CPEB1 overexpression (OE) in HFFs at 5 days post-transduction. CSTF-77 is shown as a 3′ end processing factor control. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 11. (b) RNA-seq coverage of the 3′UTR of SYNRG during HCMV and mock infection of HFFs (n=1 per condition). (c) qRT-PCR analysis of distal 3′UTR usage or proximal shift in SYNRG upon lentivirus-mediated CPEB1 OE (compared to GFP OE as a control). Error bars = mean +/− standard deviation; n=3 qRT-PCR reactions. (d) Global analysis for the presence of both a canonical CPE ((U)UUUUAU or UUUUAAU) on either side and PAS (AAUAAA or AUUAAA) upstream of RNA-seq defined 3′ proximal termination sites in increments of 150, 200, and 250 nt. 249 3′UTR shortening events, 78 lengthening events, and 638 control events were considered. Chi-square tests were performed to evaluate significance. *** P-value < 0.0001; * P-value < 0.01. (e) Venn diagram showing overlap between APA changes in CPEB1 OE and HCMV infected HFFs determined from RNA-seq data (n=1 per condition). (f) Venn diagram showing overlap of AS changes in CPEB1 OE and HCMV infected HFFs and NPCs measured by splicing sensitive microarrays (n=1 per condition per cell type). (g) RT-PCR analysis of alternatively spliced cassette exons in MYO18A, SPAG9 and USPL1 mRNA transcripts upon GFP (Control), CPEB1 and CSTF-77 OE compared to HCMV (V) infected HFFs at 48 (V-48) and 96 hpi (V-96).

CPEB1 loss reverses HCMV infection-related RNA changes

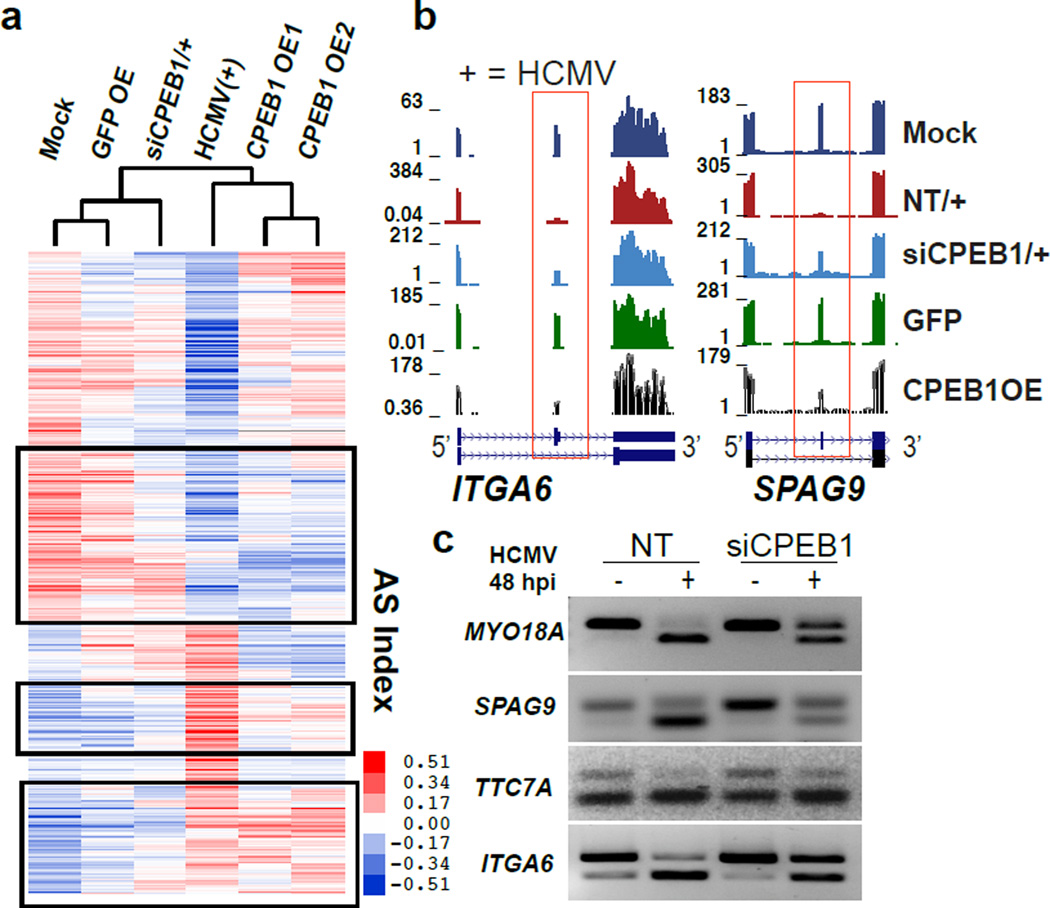

The upregulation of CPEB1 and alterations in the host RNA processing program may be important in establishing the full HCMV lytic infection, or may be a downstream effect of the infection itself. To examine these possibilities, we performed RNAi-mediated knockdown (KD) of CPEB1 in HFFs 24 h prior to infection (MOI 3) using different siRNAs, achieving >80–90% CPEB1 depletion without decreasing cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 4h,i). To determine the contribution of CPEB1 to RNA processing changes during HCMV infection of HFFs and to compare the transcriptomes of HCMV infected and CPEB1 overexpressing HFFs, we performed RNA-seq in mock and HCMV-infected cells subjected to non-targeting (NT) control siRNA and CPEB1-targeting siRNA at 48 hpi, and in HFFs overexpressing GFP (GFP OE) and CPEB1 (CPEB1 OE1 and CPEB1 OE2). Hierarchical clustering of AS changes based on exons altered during HCMV infection demonstrated that HCMV infected HFFs depleted of CPEB1 (siCPEB1) were similar to mock infected cells. Notably, HFFs overexpressing CPEB1 clustered closer to HCMV infected HFFs (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, 41% (472 of 1150) of the AS changes established during HCMV infection were either partially or completely reversed upon CPEB1 depletion (FDR <0.05, Fig. 4a, Supplementary Data Set 6). The partial reversion of AS patterns is likely due to incomplete KD of CPEB1 or from contribution of other RBPs to the regulation of these events. Evaluation of individual AS events in genes ITGA6, SPAG9 (Fig. 4b,c), TTC7A, and MYO18A (Fig. 4c) confirmed reversion upon CPEB1 depletion during virus infection by RNA-seq and RT-PCR assays. Thus, CPEB1 KD reverses HCMV infection-related AS.

Figure 4. Genome-wide host alternative splicing remodeling in HCMV infection is replicated by CPEB1 overexpression and corrected by CPEB1 depletion.

(a) Hierarchical clustering of alternatively spliced exon indices (as a measure of exon inclusion by RNA-seq in HFFs). Boxed regions highlight a reversal of HCMV infection-related AS (MOI 3). The color bar shows the scale of exon inclusion (+ values) and exclusion (- values) relative to the mean splicing index values when comparing across samples. 472 exons showed reversal as reported in Supplementary Data Set 6 (FDR<0.05, dI >|0.1|). For RNA-seq, n=1 each for mock-NT siRNA, HCMV infected-NT siRNA, HCMV infected-siCPEB1 treated, and GFP OE samples, and n=2 for CPEB1 OE samples. (b) RNA-seq coverage of AS exons (boxed) in ITGA6 and SPAG9 in all conditions in HFF cells (NT is non-targeting siRNA. (c) RT-PCR analysis of AS cassette exons (4/4 selected and validated) of MYO18A, SPAG9, TTC7A, and ITGA6 in either mock (−) or HCMV (+) infected cells treated with either non-targeting (NT) or CPEB1 siRNA.

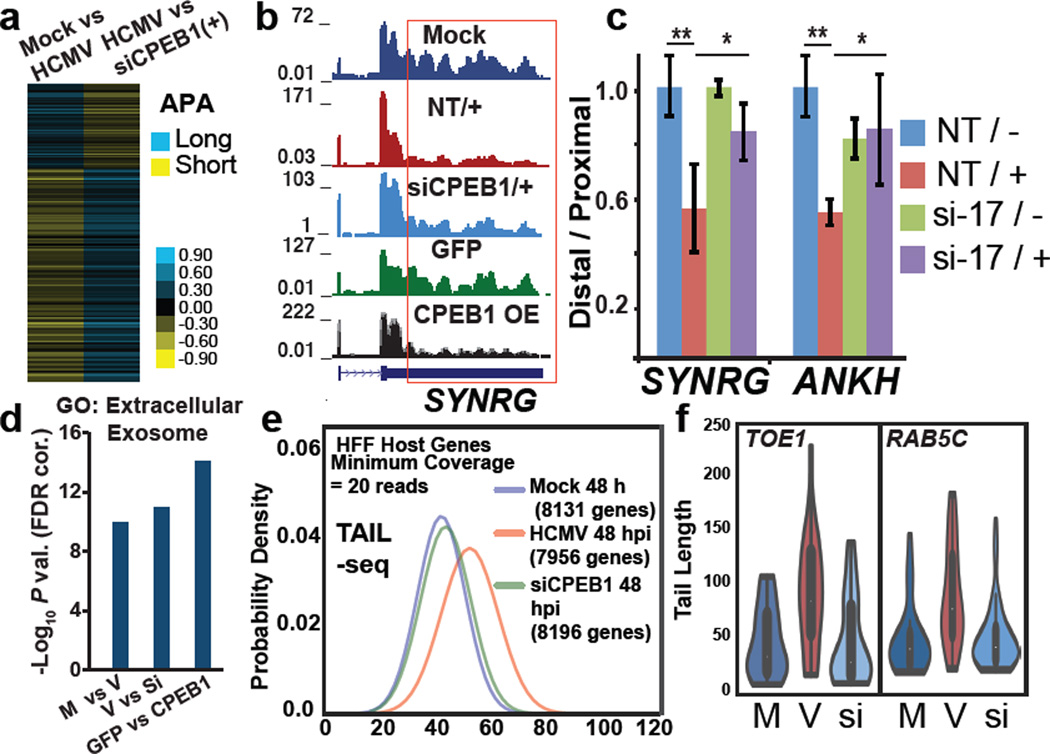

Global APA analysis showed primarily 3′UTR shortening during infection (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and with CPEB1 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 5b), with a significant overlap (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In contrast, 3′UTR lengthening was observed with CPEB1 depletion in infected cells (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 5d,e, Supplementary Data Set 3). 196 (of 473, 41%) APA changes in HCMV infection were either partially or completely reversed with CPEB1 KD (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 5f). Transcripts SYNRG and ANKH that exhibited 3′UTR shortening during infection maintained their longer 3′UTR in infected cells upon CPEB1 KD (Fig. 5b,c) and PCGF3 and ANKH showed 3′UTR shortening in CPEB1 OE HFFs (Supplementary Fig. 5g). Importantly, depletion of CSTF64, a factor known to affect 3′ cleavage and polyadenylation of pre-mRNAs did not have this effect (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Interestingly, gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes harboring APA changes using DAVID 33 and STRING 34 (Supplementary Data set 7) showed an enrichment in GO terms “extracellular exosome” (P value = 7.61×10−14) and “Golgi apparatus” (P value = 1.3×10−7) in HCMV infected HFFs. These categories were further enriched in siCPEB1 (reversal or lengthening events; P values = 2.87×10−17 and 2.36×10−9) and CPEB1 OE (shortening events, P values = 5.7×10−18 and 1.5×10−8) altered events (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5h). We conclude that CPEB1 KD reverses HCMV infection-related 3′UTR shortening.

Figure 5. HCMV infection related host genome-wide 3′UTR shortening and polyA tail lengthening in HCMV infection is reversed by CPEB1 depletion.

(a) Heatmap showing 3′UTR shortening (yellow) and lengthening (blue) in Mock vs. HCMV and HCMV vs. siCPEB1 infected cells for 196 genes (Bayes Factor > 10000) common between two RNA-seq datasets (n=1 per condition) (b) RNA-seq coverage of SYNRG 3′UTR in all conditions in HFF cells. Infected cells are indicated by “+”. NT is non-targeting siRNA. (c) qRT-PCR analysis of distal 3′UTR usage in SYNRG and ANKH transcripts in either mock (−) or HCMV (+) infected cells treated with either non-targeting (NT) or CPEB1 siRNA (si-17). Error bars are standard deviation between replicates (n=3 qRT-PCR replicates) and ** P-value < 0.005; * P-value < 0.05 as calculated by Student’s t-test. (d) DAVID gene ontology (GO) shows progressive enrichment of the extracellular exosome category in mock (M) vs. HCMV (V), HCMV (V) vs. siCPEB1 (Si) (+HCMV), and GFP OE vs. CPEB1 OE. (e) Median polyA tail lengths determined by TAIL-seq (n=2 MiSeq runs per condition, datasets from two runs were pooled for final analysis) in HCMV infected HFFs (MOI 3) vs. mock controls and siCPEB1 treated HFFs (+HCMV). (f) Violin plots showing distribution of polyA tail lengths for TOE1 and RAB5C transcripts (mock vs. infection P values <0.0025, 5×10−5 by Mann Whitney U test, respectively; Infection vs. siCPEB1 P values <0.0015, <2×10−6 by Mann Whitney U test, respectively).

Since cytoplasmic CPEB1 levels are also higher, we reasoned CPEB1 may also modulate polyA tail lengths of both host and viral genes in HCMV infected HFFs 22. We performed transcriptome-wide polyA tail length analysis using TAIL-seq (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 6a) 25, which revealed that median polyA tail lengths of host genes were increased during HCMV infection (Fig. 5e). Critically, CPEB1 depletion decreased the median tail lengths to mock infection levels (Fig. 5e,f). GO analysis of host genes with shortened polyA tails after siCPEB1 depletion showed enrichment (P value = 6×10−21) in the “membrane enclosed lumen” category (Supplementary Data set 8, Supplementary Fig. 6b). We conclude that CPEB1 depletion during HCMV infection reverses a large fraction of infection-induced RNA processing changes, including host polyA tail lengths.

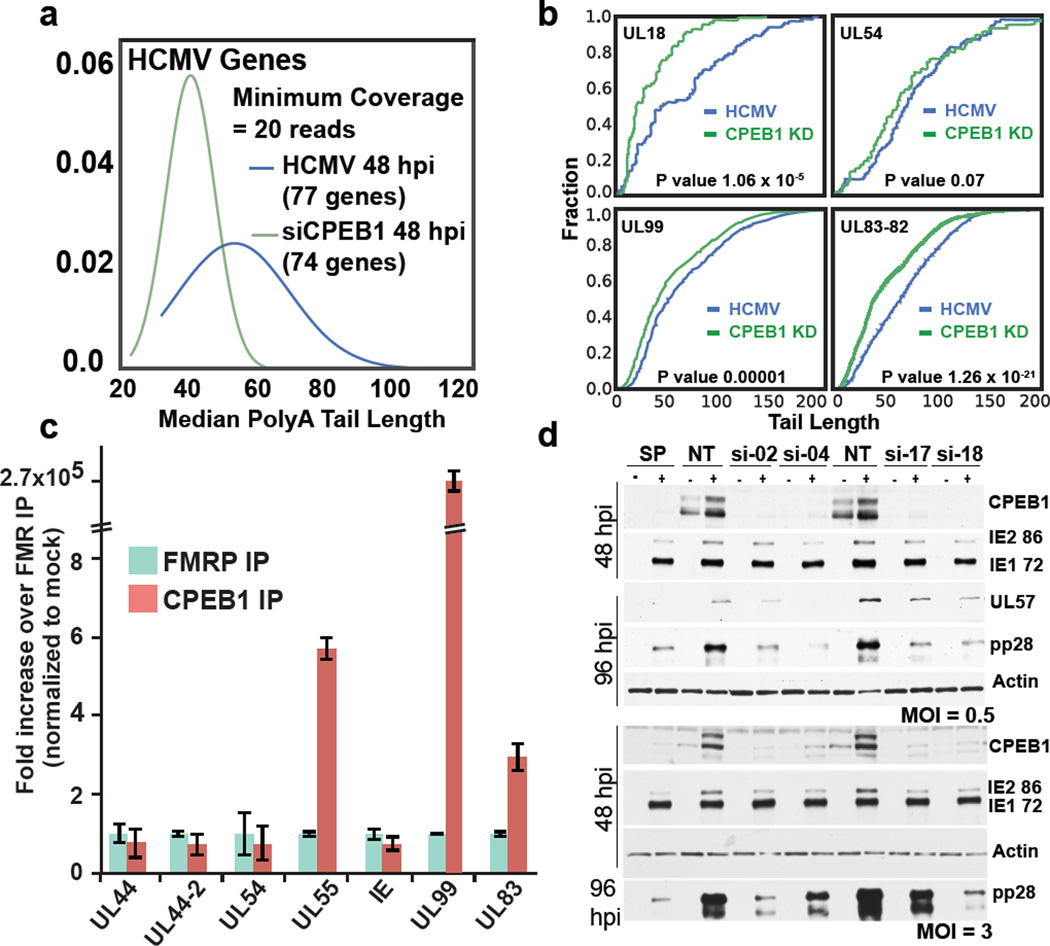

CPEB1 depletion shortens polyA tails in HCMV genes

TAIL-seq analysis of HCMV transcripts in infected (+) and siCPEB1 (+) HFFs showed a decrease in median polyA tail length with CPEB1 depletion (Fig. 6a). For example, HCMV transcript UL18, an MHC I class homolog that participates in host immune system evasion, 35 showed the largest decrease in mean and median polyA tail length (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Data Set 8). PolyA tail length in UL83-UL82 bicistronic transcript was also reduced after CPEB1 depletion, whereas UL54 did not show a significant change by Mann-Whitney U test (P value = 0.06; Fig. 6b). We performed crosslinking and immunoprecipitation coupled with quantitative RT-PCR (CLIP-PCR) to evaluate if CPEB1 directly binds to viral transcripts. Indeed, we observed highly enriched CPEB1 binding to UL99 transcript, which had statistically significant differences in poly A tail length (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Data Set 8) upon CPEB1 depletion, relative to binding of an unrelated RBP Fragile X mental retardation protein (Fig. 6c). CPEB1 binding to UL83 and UL55 transcripts was also enriched three-fold and five-fold over control, respectively (Fig. 6c). Other viral transcripts such as UL55 that were bound by CPEB1 were not supported by enough TAIL-seq reads for polyA tail length detection (Supplementary Data Set 8). To assess if changes in viral protein levels also accompanied polyA tail length alterations, we performed immunoblot analysis of viral proteins. Our results revealed that the level of the late viral protein pp28 (UL99) was consistently lower in the CPEB1-depleted HCMV-infected (+) HFFs, whereas the immediate early proteins IE-72 and IE-86 showed no changes (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6. CPEB1 depletion by siRNA results in shortened polyA tail lengths and decreased protein levels of HCMV late genes.

(a) TAIL-seq distributions (n=2 MiSeq runs per condition, datasets from two runs were pooled for final analysis) of median polyA tail lengths for viral genes in HCMV infected HFFs and infected HFFs treated with siCPEB1. (b) Cumulative distribution frequency (CDF) plots of polyA tail length distributions for UL18, UL99, UL83-82-containing and UL54 HCMV transcripts (P values <10−5, <0.00014, <10−20, 0.06, by Mann Whitney U test). (c) UV crosslinking followed by immunoprecipitation coupled with qPCR (CLIP-PCR) for RNA targets bound by CPEB1 and FMRP. n=3 qRT-PCR replicates. (d) Immunoblot analysis of CPEB1 and viral proteins (IEs, UL57, and pp28) in mock (indicated as “−”) or HCMV (TB40E) infected cells (indicated as “+”) treated with either non-targeting (siNT) or four different CPEB1-targeting siRNAs (si-02, si-04, si-17, si-18) at MOIs 0.5 (upper) and 3 (lower). β-actin was used as a loading control. SP stands for smartpool (mixture) of four different siRNAs against CPEB1. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 11.

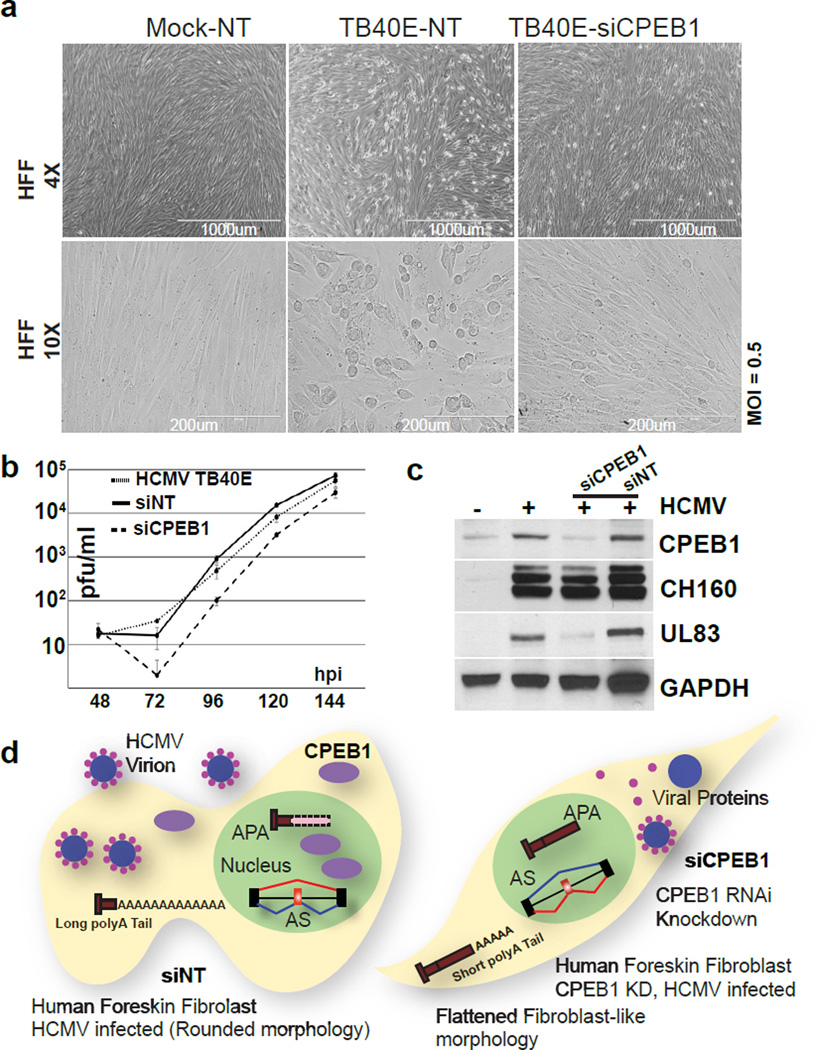

CPEB1 is necessary for productive HCMV infection

To evaluate the cellular effects of CPEB1 depletion on viral infection, we analyzed siCPEB1 treated, HCMV-infected HFFs. The morphology of the infected HFFs (MOI 0.5) with CPEB1 depletion at 48 hpi dramatically exhibited a visible rescue of the cytopathic effects normally observed post-infection, when compared to the infected cells treated with non-targeting control siRNA (Fig. 7a). The infected siCPEB1 HFFs maintained fibroblast-like characteristics similar to healthy mock-infected cells. Productive HCMV titers established using a plaque forming assay showed ~10-fold reduction with siCPEB1 over NT-siRNA transfected HFFs at 96 hours (Fig. 7b). The titers recovered, at least partially, by 144 hpi. Importantly, overexpression of the UL99 encoded protein pp28 alone in siCPEB1-treated, HCMV-infected cells did not result in infection-related morphology at 48 hpi while lentivirus-mediated expression of codon-optimized CPEB1-GFP fusion that is insensitive to the CPEB1-specific siRNA recapitulates the infection-related morphology in cells (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Indeed, another late protein such as UL83 encoded pp65 was also decreased with CPEB1 depletion (Fig. 7c). As an orthogonal approach to deplete CPEB1, we used uniformly modified 2’-O-methoxyethyl antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) with a phosphorothioate backbone against exon 5 in CPEB1 (Supplementary Data Set 9, Supplementary Fig. 6d,e). ASO-mediated depletion of CPEB1 reduced the viral pp28 protein and rescued AS changes in SPAG9 (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Therefore, we conclude that CPEB1 is necessary for shaping the RNA landscapes of host and HCMV genes to support productive infection (Fig. 7d).

Figure 7. CPEB1 depletion rescues cytopathology and attenuates HCMV infection.

(a) Phase contrast images of mock or HCMV (TB40E) infected cells treated with either non-targeting (NT) or CPEB1 siRNA (siCPEB1) at low (top; scale bar representing 4×) and high (bottom; scale bar representing 10×) magnifications. Experiment was repeated a total of three times and representative pictures are shown. (b) Productive HCMV viral titers at different time points determined by plaque assay for TB40E infected cells (HCMV TB40E), TB40E infected cells treated with non-targeting (siNT), and TB40E infected cells treated with CPEB1 siRNA (siCPEB1). (c) Immunoblot analysis of CPEB1 and viral proteins (IEs CH160, UL83) in mock (indicated as “−”) and HCMV (TB40E) infected cells (MOI 0.5; indicated as “+”) that are untreated or treated with non-targeting (NT) or CPEB1-targeting siRNA (si17). GAPDH was used as a loading control. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 11. (d) Our working model summarizes our findings describing HCMV infection in the presence (left) and absence (right) of CPEB1. HCMV infection induces CPEB1 expression which supports certain AS isoforms, shorter 3’UTRs, longer polyA tail lengths and normal productive HCMV titers, whereas CPEB1 depletion leads to preservation of normal 3′UTR lengths, polyA tail lengths, and decreased productive HCMV titers.

Discussion

Human genes are subject to post-transcriptional regulation at the level of AS, APA and polyA tail lengths during development 17,18,24,36. AS and APA are also perturbed in neuromuscular diseases and cancer 17,19,37. However, the scale at which and how RNA processing events in host genes are affected by viral infection has not been widely appreciated. In our study, despite the wide cellular tropism that distinguishes HCMV, we observed a convergence at the level of RNA processing among different infected cell types. Transcriptome-wide measurements revealed commonly altered AS events in different cell types, suggesting shared, cell-type independent pathways affected by HCMV. AS changes can lead to the production of different proteins either by altering the coding sequence of transcripts or by decreasing protein levels through frameshifts and nonsense mediated decay, either of which can change the cellular environment to support viral replication. During infection, the majority of the altered transcripts favored usage of a proximal polyA site resulting in decreased 3′UTR lengths that can lead to changes in stability, localization, and/or translation of the affected transcript. 3′UTR shortening is known to occur in highly proliferative states such as cancer 37,38. Furthermore, B cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) demonstrate reduced 3′UTR lengths for a number of host transcripts 39. However, EBV establishes a latent infection and immortalizes B cells, and the altered host polyadenylation patterns appear to be a consequence of the associated proliferation rather than the infection itself 39. However, during lytic HCMV infection, the cells are not proliferative, indicating that global 3′UTR shortening is not a secondary effect of proliferation.

Identification of RBPs that are responsible for host and viral RNA processing changes during virus infections will provide key insights into mechanisms of viral propagation and transmission and are potential therapeutic targets. We observed consistent upregulation of the RBP CPEB1 in all three primary cell types analyzed. CPEB1 is a well-studied RBP that plays an essential role in early development and neuronal function 22,32,40. CPEB1 is known to interact with the splicing factor U2AF65 32 and 3’end machinery proteins CPSF-73 and CSTF-64 41. CPEB1 binds a consensus sequence (UUUUUAU), termed the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE), in introns and 3′UTRs proximal to polyA signals 42–44 and affects AS 41 and APA in candidate transcripts and mini-gene reporters 32. Our analysis revealed a striking enrichment in CPEs in the proximity of HCMV infection-altered 3′-end cleavage sites compared to unaffected 3′-ends. Ectopic expression of CPEB1 in non-infected cells led to a sizable fraction of AS and APA events reminiscent of RNA processing patterns in HCMV infection. Congruently, CPEB1 depletion during HCMV infection reversed hundreds of RNA processing events towards the mock-infected patterns. Gene sets altered in APA during infection, CPEB1 overexpression, and CPEB1 depletion (during infection) showed enrichment in “extracellular exosomes” and “Golgi apparatus” categories. This is particularly salient because HCMV packaging occurs in a membrane-enclosed compartment that contain markers for both trans-Golgi network (TGN) and endosomes 45. Furthermore, exosomes and microvesicles (enriched GO terms) can contribute to viral packaging, progression of viral infection, host immune system evasion and allograft rejection 46 47 48 49.

In the cytoplasm, CPEB1 is linked to the alteration of cytoplasmic polyadenylation and translation of genes involved in cellular senescence 50,51. For example, p53 mRNA has an abnormally short polyA tail and a reduced translational efficiency in CPEB1 KD cells 50. In our study, transcriptome-wide analysis of polyA tail lengths using TAIL-seq showed an increase in polyA tail lengths of host genes during HCMV infection. This is in contrast with Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) infection, in which a viral protein called SOX leads to extended polyA tails, nuclear retention, and reduced gene expression of host transcripts52. We did not observe reduced gene expression of the host transcripts with lengthened polyA tails. Furthermore, siRNA mediated depletion of CPEB1 during HCMV infection not only shortened the median polyA tail lengths to normal levels but also decreased the tail lengths of viral transcripts. GO analysis of host genes with shorter polyA tail lengths after CPEB1 depletion showed an enrichment of “membrane enclosed lumen” and “protein localization” categories, pointing to viral assembly pathways. Indeed many members of the small Ras related protein family (RABs, small GTPases) were altered including RAB27A, which is important for HCMV assembly 53. We show that HCMV UL99 and UL83 genes contained in multi-cistronic transcripts have shorter polyA tails and reduced protein expression after CPEB1 knockdown during infection. Furthermore, CPEB1 directly interacts with viral RNAs that contain UL99 and UL83. UL99-encoded pp28 is a tegument protein that is essential for final viral envelopment, and a previous report showed that pp28 knockouts (KO) do not produce virions and infection is attenuated 54. UL83 encodes a tegument phosphoprotein that inhibits cellular antiviral response. It is notable that both UL83 and UL99 gene products (tegument proteins pp65 and pp28, respectively) are known to interact with each other and also with host Golgi and exosomes 55–57. Therefore, CPEB1 affects both host and viral components involved in viral assembly.

Our analysis of the consequences of CPEB1 depletion on progression of HCMV infection by evaluating cellular morphology and productive viral titers revealed that cells became rounded and had bulging nuclei and nuclear inclusions 48–72 hpi 58,59. We demonstrated that depletion of CPEB1 not only reverses these cytopathic changes but also decreases the productive HCMV titers by ~10 fold at 96 hpi. The titers eventually recovered at later time points, likely due to eventual loss of transiently delivered siRNA and resurgence of CPEB1. During infection, CPEB1 KD led to a decrease in UL99 protein product pp28. We found that exogenous expression of UL99 alone using lentiviruses in the context of CPEB1 depletion was not sufficient to generate HCMV cytopathology. This implies that CPEB1-mediated effects on other HCMV transcripts and proteins may be important for virus infection. Indeed, the late gene UL83 protein product pp65 was also downregulated after CPEB1 depletion during HCMV infection. The immediate early proteins IE 86 and IE 72 were not affected, implying that viral infection is established but CPEB1 is required for late stages of virus infection. As CPEB1 alters host and viral transcripts involved in viral packaging and transport (later stages in infection), our two results of viral packaging dysfunction and inhibition of late infection stages are in strong agreement.

In summary, we demonstrate an unexpected role for CPEB1 induction in productive HCMV infection in HFFs. Our study provides original evidence for the importance of modulating host alternative polyadenylation in host-virus interactions and identifies a new player in host-virus interactions. CPEB1 may not be the only host factor that shapes the host RNA landscape for establishing HCMV or other viral infections, and it is likely that other RBPs may be involved. Future work will be important to identify mechanisms of CPEB1 induction, establish a direct connection between CPEB1 binding and RNA processing with mini-gene reporters, and understand the role of other cellular RBPs that affect host and viral RNA landscapes. Finally, this study sheds light on mechanisms of cellular susceptibility to HCMV infection and provides a potential therapeutic target for HCMV. These host mechanisms may extend to other members of the herpesvirus family and further efforts will be needed to uncover the host RBP-RNA networks dysregulated in DNA virus infections.

Methods

Cell types

Neural precursor cells (NPCs) were derived from H9 and HUES9 human embryonic stem cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). We used primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs), as in Belzile et al. J Virol. 2014 Apr;88(8):4021-39 30, and Endothelial cells (ECs) as in DuRose et al. J Virol. 2012 Dec;86(24):13745-55 6. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert mycoplasma test kit (Lonza) and were found negative for mycoplasma.

Virus infections

All TB40E HCMV infections were performed as recently described 30. HUES9-derived NPCs were mainly used for this study, and H9-derived cells were used in extended follow-up comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 3d and 3e). Towne HCMV infections (RT-PCR comparisons shown in Fig. 1c) were conducted at an MOI of 3. For Interferon-gamma (IFN-g) treatment, 500U or 25ng/ml of recombinant IFN-g (Abcam ab9659) in MEM + 10% FBS was used for the treatments of HFFs. For UV treatment, HCMV was exposed to a dose of 400mJ/cm2 of UV light in a Stratalinker (Stratagene). HSV-2 infections were performed in HFFs with strain G at an MOI of 10. For HSV-2, following an initial 30 min adsorption period at 4°C, mock-infected and infected cells were incubated at 37°C and harvested at 2 and 8 hpi. All HCMV and HSV-2 materials were collected at the time of harvest by trypsinization, briefly pelleted, and snap-frozen prior to subsequent analysis.

RNA-seq library preparation and data processing

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent using the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies). For all the HCMV TB40E infection and mock-infection conditions, we prepared strand-specific libraries using the dUTP method 60 with adaptations described in detail previously 28. For the TB40E and mock-infected HFFs and ECs, adaptor-containing oligo(dT) was included during first-strand cDNA synthesis (cDNA Cloning Primer, ReadyMade Primers, Integrated DNA Technologies). Libraries for the comparative analysis of Mock, HCMV, siCPEB1, and CPEB1 OE samples were prepared with Illumina TruSeq polyA mRNA Sample Preparation reagents. All samples were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform. Each sample was barcoded, multiplexed and run together. Cluster 3.0 software and Java Treeview were used in combination to perform and visualize results from hierarchical gene expression clustering results. Libraries for analysis of HSV-2 infections were prepared with Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation reagents. All samples were sequenced on the Illumina Hi-Seq platform. HSV-2 samples were multiplexed and run together.

Analysis of HCMV gene expression

For HCMV mRNA abundance measurements, we used the newly available TB40E genome sequence (Genbank KF297339.1, strain ‘Lisa’) for mapping and analysis of coverage of Genbank-listed HCMV ORF annotations. Data processing was also performed with the HCMV Merlin reference to facilitate comparisons to the Gatherer et al. and Stern-Ginossar et al. studies 13 14.

Analysis of human alternative splicing and polyadenylation

Splicing-sensitive microarray analysis was performed as previously described 28. RT-PCR splicing assays were performed using the equivalent of 50 ng of oligo(dT)-primed cDNA (reverse transcription performed with Superscript III, Life Technologies) and 35 cycles of PCR amplification. For AS analysis of RNA-seq data we used Olego and Quantas software suite as previously described 63 19. Tandem UTR isoform analysis was performed with the MISO algorithm v0.5.2 using default settings 27, except for use of custom 3′UTR isoform annotations. We used a Bayes-factor threshold of 10,000 and difference values (delta Psi) with an absolute value of at least 0.03 (although the cutoff selected for this latter value is low, we found significant degrees of UTR shift from this value upwards when used in combination with the high Bayes-factor for the HCMV samples). To generate the custom annotations, we downloaded all Ensembl-defined human 3′UTR regions (http://uswest.ensembl.org, Release 75) and flattened them with the mergeBed function from Bedtools v2.16.2 (to define 3′UTR starts). Collapsed UTR regions harboring more than one cleavage site detected by RNA-seq were considered, with a minimum threshold of five reads required to constitute a polyA site. These cleavage-defining reads were based on human-mapped polyA6+-containing RNA-seq reads (filtering performed for genomic regions with A-tracts). Finally, the two termination sites with the highest coverage were selected to define putative proximal and distal alternative ends of the 3′UTR. We generated one index based on polyA reads from the infected NPCs and another that was based on a composite of infected HFF and EC polyA reads (neuronal vs. non-neuronal was sufficient for this analysis and we had obtained 1.5-2X sequencing depth in the NPC samples vs. the HFF and EC libraries). Indexed annotations were generated separately for the HSV-2 condition, again based on the samples’ own polyA-RNA-seq reads. qRT-PCR analysis of alternative 3′UTR isoforms was performed as described 16. 1 µg of total RNA was first DNase-treated, and only oligo(dT) was used for cDNA synthesis (generated with Superscript III, Life Technologies). All primer sequences for RT-PCRs and qPCRs are provided in the Supplementary Data Set 10.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared from −80°C-stored cell pellets with RIPA lysis buffer, on ice. Following brief sonication, lysates were clarified by 12,000 × g centrifugation for 10–15 min. Samples were loaded according to total protein content, determined by BCA assessment (Thermo Pierce), and within each cell type the amounts were normalized to the first mock-infected sample (corresponding to ~100,000 cells total per lane). Antibodies and dilutions used: CSTF-64 (A301-092A), CSTF-77 (A301-096A), and CFIm-68 (A301-356A): Bethyl Laboratories, 1:2000. CPEB1: Cell Signaling Technologies (13583), 1:1000. β-actin: Sigma-Aldrich (clone AC-15, A1978), 1:10,000. Ms anti IE (CH160): Virusys, 1:5000. Ms anti UL57: Virusys, 1:1000. Ms anti UL99(pp28): Virusys, 1:1000. Ms anti UL83(pp65) Virusys, 1:5000.

Lentiviral vector production and transduction

Human CPEB1 open reading frame was PCR amplified from HFF cDNA with the following primers: Forward GCCCGCTGCAAAAATAGTG and Reverse TCAGCAAGTGCAAAGGTGAC. The PCR product was first cloned into the Topo-TA vector pCR2.1 (Life Technologies). CMV-turboGFP from pGIPZ (Open Biosystems) was replaced with the CMV promoter from pCDNA3.1- (Life Technologies), and the cloned CPEB1 was inserted at SpeI and NotI restriction sites. CPEB1, UL99 and control GFP lentiviruses were generated in 293T cells with PEI transfection reagent, in 10 cm format with 107 cells per dish, using the second generation packaging constructs psPAX2 and pMD2.G. Supernatants were harvested at 60 h post-transfection and 0.22 µm filtered. Freshly seeded HFFs were transduced at an MOI of 0.5 to 1, without polybrene or additional reagents. Puromycin selection was initiated in the transduced HFFs at 48 h, and cells were harvested following 3 days of drug selection.

TAIL-seq

TAIL-seq was performed as described by Chang et al 25, with minor modifications. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from cells by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596-018) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA ligated to 3′ “splint” oligonucleotide (NNNGTCAGTTTTTTTTT) to enrich for polyadenylated transcripts and partially digested by RNase T1 (Ambion, AM2283). The fragmented RNAs were pulled down with Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin (Invitrogen, 11206D) magnetic beads, phosphorylated on bead using T4-PNK reaction (NEB), eluted using 2X RNA loading dye (with 95% formamide), run on a 6% polyacrylamide urea gel (NuPage), stained with SYBR gold (Thermo) and gel purified in the range of 250 – 750 nucleotides. The purified RNAs were ligated to 5′ adapter (Illumina Truseq small RNA kit), reverse transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) and amplified by PCR using Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo, F-530L) and Illumina Truseq small RNA universal forward and indexed (barcode) reverse primer(s). The library was purified using AMPureXP beads (Agilent) and the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (51 ~ 251 paired end run) with 10% of the PhiX control library (Illumina, FC-110-3001) and 1% of the spike-ins mixture of known polyA-containing DNAs 25. All adapters and primers were synthesized by IDT. For TAIL-seq data analysis, image files were downloaded from the MiSeq and run on tailseeker2 25 to determine accurate polyA tail lengths, yielding paired fastq files corresponding to the 5’ (R5) and 3’ (R3 polyA tail) ends of each read. Reads were aligned against the human genome (hg19) and viral genomes (Human_Herpesvirus_5_strain_Merlin) using STAR under default parameters. Features were assigned using Subread with gencode v19 annotations and with Human_Herpesvirus_5_strain_Merlin features, and filtered to obtain only the uniquely mapped protein coding genes. For analysis of virally mapped reads, all genes were counted. Reads with tails measuring 0 lengths were removed. For genes with at least 20 mapped reads, median lengths were measured and the global distributions of these lengths were compared against each other using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For each gene captured in all samples and with at least 20 mapped reads, individual tail length distributions were compared amongst samples using the Mann Whitney U test with a P value cutoff of 0.025.

Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) transfections

5×104 HFFs were seeded per well of a 12 well plate. For each ASO, 2 µl of 200uM stock ASO was mixed with 100 µl of OptiMEM (Gibco) and 3 µl of RNAiMax (Life Sciences), incubated for 30 mins at room temperature and added to the respective well. HCMV infection was initiated 24 hours post ASO transfection.

Statistical Methods

The qPCRs were compared in a pairwise analysis and P values were calculated using a Student’s t-test for technical replicates. The error bars are reported as standard deviation or standard error of the technical replicates as mentioned in the respective Fig. legends. Genome-wide APA analysis was done using the MISO algorithm v0.5.2 and Bayes factor and delta psi values were calculated. Bayes factor represents the weight of the evidence in the data in favor of differential expression versus not as described by Katz et al 27. We used a Bayes-factor threshold of 10,000 and difference values (delta Psi) with an absolute value of at least 0.03. A Bayes factor of 10,000 that APA switch is 10,000 times more likely to occur than not. For gene expression, reads were trimmed for adaptor sequences or low-quality bases and then mapped to both the human genome (hg19 build) and the HCMV Merlin genome (Genbank AY446894.2) with GSNAP. Additional filtering of reads that mapped to repetitive elements was also performed. Gene expression values (RPKM 61) were calculated within each sample, and Z-score analysis was implemented to identify significant differences in expression as previously described 62. For AS analysis, we followed the procedure described in Charizanis et al 19. For each pair of reads that spanned one or more exons (up to three, which is sufficient in practice given the fragment size), all possible isoforms (paths) between the anchored ends were found, and the probability of each isoform to be the actual origin of the paired-end reads was estimated. Each inferred fragment was assigned a probability score. This junction inference step substantially increased the effective number of fragments supporting exon junctions, especially for cassette exons, and increased statistical power in detecting splicing changes. The weighted number of exon or exon-junction fragments uniquely supporting the inclusion or skipping isoform of each cassette exon were counted and a Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of splicing changes using both exon and exon-junction fragments, followed by Benjamini-Hochberg multiple hypothesis testing correction to estimate the false discovery rate (FDR). Differential splicing events were identified by requiring FDR <0.05 and |ΔI| ≥0.1. For TAIL-seq data analysis, image files were downloaded from the MiSeq and run on tailseeker2 25 to determine accurate polyA tail lengths, yielding paired fastq files corresponding to the 5’ (R5) and 3’ (R3 polyA tail) ends of each read. Reads were aligned against the human genome (hg19) and viral genomes (Human_Herpesvirus_5_strain_Merlin) using STAR under default parameters. Features were assigned using Subread with gencode v19 annotations and with Human_Herpesvirus_5_strain_Merlin features, and filtered to obtain only the uniquely mapped protein coding genes. For analysis of virally mapped reads, all genes were counted. Reads with tails measuring 0 lengths were removed. For genes with at least 20 mapped reads, median lengths were measured and the global distributions of these lengths were compared against each other using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For each gene captured in all samples and with at least 20 mapped reads, individual tail length distributions were compared amongst samples using the Mann Whitney U test with a P value cutoff of 0.025.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Yeo and Spector labs for critical reading of the manuscript and extend particular acknowledgement to M.T. Lovci for initial assistance with bioinformatics. We thank Hyeshik Chang (Narry Kim lab, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) for help with the Tailseeker algorithm and Sarah Azoubel Lima and Amy Pasquinelli at UCSD for sharing their modified TAIL-seq protocol prior to publication. We especially thank C.S. Morello for assistance with HSV-2 infections, and the laboratory of S.A. Spector for HIV-1-infected materials. This work was partially supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (HG004659, HG007005 and NS075449) to G.W.Y. and from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (RB3-05219) to G.W.Y. and D.H.S. T.J.S. and E.C.W are supported in part by the University of California, San Diego, Genetics Training Program through an institutional training grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, T32 GM008666. E.C.W. is a NSF Graduate Student Research Fellow. R.B. is a myotonic dystrophy foundation postdoctoral fellow. G.W.Y. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

R.B., T.J.S., D.H.S. and G.W.Y. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; A.E.C., and J.P.B., maintained HCMV viral stocks, measured titers and performed HCMV infections; R.B., T.J.S., and A.E.C. performed siRNA treatments. T.J.S., A.E.C, and R.B., performed western blots. R.B. performed immunofluorescence and microscopy. T.J.S. and T.B. made lenti-virus preps. R.B., T.J.S., and E.C.W. made RNA-seq libraries. R.B., T.J.S., S.H., B.A.Y and S.S. performed bioinformatics analysis. R.B. and T.J.S. performed RT-PCR splicing and APA assays. H.H. and R.B. prepared TAIL-seq libraries, overseen by S.A. C.G.B. performed microarray array hybridizations. S.H., J.P.D., and M.A. performed microarray analysis.

Competing Financial Interests Statement

F.R. is a paid employee of Ionis Pharmaceuticals, which provided ASO reagents.

Accession Numbers

The NCBI GEO accession number for the sequencing data and splicing sensitive microarrays reported in this paper is GSE74250.

References

- 1.Staras SA, et al. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1143–1151. doi: 10.1086/508173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mocarski ES, et al. Betaherpes viral genes and their functions. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. 2007:204–230. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortunato EA, McElroy AK, Sanchez I, Spector DH. Exploitation of cellular signaling and regulatory pathways by human cytomegalovirus. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:111–119. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Pass RF. Cytomegaloviruses. In: Howley DMKaPM., editor. Fields’ virology. 5th. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2701–2772. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell LA, Rosenfeld ME. Infection and Atherosclerosis Development. Arch Med Res. 2015;46:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuRose JB, Li J, Chien S, Spector DH. Infection of vascular endothelial cells with human cytomegalovirus under fluid shear stress reveals preferential entry and spread of virus in flow conditions simulating atheroprone regions of the artery. J Virol. 2012;86:13745–13755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02244-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuessler A, Walker DG, Khanna R. Cytomegalovirus as a novel target for immunotherapy of glioblastoma multiforme. Front Oncol. 2014;4:275. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvath R, et al. The possible role of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in the origin of atherosclerosis. J Clin Virol. 2000;16:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(99)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenwick ML, Walker MJ. Suppression of the synthesis of cellular macromolecules by herpes simplex virus. J Gen Virol. 1978;41:37–51. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-41-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sydiskis RJ, Roizman B. Polysomes and protein synthesis in cells infected with a DNA virus. Science. 1966;153:76–78. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3731.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwong AD, Frenkel N. Herpes simplex virus-infected cells contain a function(s) that destabilizes both host and viral mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1926–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hertel L, Mocarski ES. Global analysis of host cell gene expression late during cytomegalovirus infection reveals extensive dysregulation of cell cycle gene expression and induction of Pseudomitosis independent of US28 function. J Virol. 2004;78:11988–12011. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11988-12011.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatherer D, et al. High-resolution human cytomegalovirus transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19755–19760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115861108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stern-Ginossar N, et al. Decoding human cytomegalovirus. Science. 2012;338:1088–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1227919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poulos MG, Batra R, Charizanis K, Swanson MS. Developments in RNA splicing and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a000778. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulitsky I, et al. Extensive alternative polyadenylation during zebrafish development. Genome Res. 2012;22:2054–2066. doi: 10.1101/gr.139733.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batra R, et al. Loss of MBNL leads to disruption of developmentally regulated alternative polyadenylation in RNA-mediated disease. Mol Cell. 2014;56:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scotti MM, Swanson MS. RNA mis-splicing in disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:19–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charizanis K, et al. Muscleblind-like 2-mediated alternative splicing in the developing brain and dysregulation in myotonic dystrophy. Neuron. 2012;75:437–450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenal M, et al. The poly(A)-binding protein nuclear 1 suppresses alternative cleavage and polyadenylation sites. Cell. 2012;149:538–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Klerk E, et al. Poly(A) binding protein nuclear 1 levels affect alternative polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9089–9101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter JD. CPEB: a life in translation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scorilas A. Polyadenylate polymerase (PAP) and 3’ end pre-mRNA processing: function, assays, and association with disease. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2002;39:193–224. doi: 10.1080/10408360290795510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subtelny AO, Eichhorn SW, Chen GR, Sive H, Bartel DP. Poly(A)-tail profiling reveals an embryonic switch in translational control. Nature. 2014;508:66–71. doi: 10.1038/nature13007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang H, Lim J, Ha M, Kim VN. TAIL-seq: genome-wide determination of poly(A) tail length and 3’ end modifications. Mol Cell. 2014;53:1044–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Licatalosi DD, et al. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature. 2008;456:464–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz Y, Wang ET, Airoldi EM, Burge CB. Analysis and design of RNA sequencing experiments for identifying isoform regulation. Nat Methods. 2010;7:1009–1015. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huelga SC, et al. Integrative genome-wide analysis reveals cooperative regulation of alternative splicing by hnRNP proteins. Cell Rep. 2012;1:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gehman LT, et al. The splicing regulator Rbfox1 (A2BP1) controls neuronal excitation in the mammalian brain. Nat Genet. 2011;43:706–711. doi: 10.1038/ng.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belzile JP, Stark TJ, Yeo GW, Spector DH. Human cytomegalovirus infection of human embryonic stem cell-derived primitive neural stem cells is restricted at several steps but leads to the persistence of viral DNA. J Virol. 2014;88:4021–4039. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03492-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo W, et al. The Conserved Intronic Cleavage and Polyadenylation Site of CstF-77 Gene Imparts Control of 3’ End Processing Activity through Feedback Autoregulation and by U1 snRNP. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bava FA, et al. CPEB1 coordinates alternative 3’-UTR formation with translational regulation. Nature. 2013;495:121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature11901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim Y, et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL18 utilizes US6 for evading the NK and T-cell responses. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batra R, Manchanda M, Swanson MS. Global insights into alternative polyadenylation regulation. RNA Biol. 2015;12:597–602. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1040974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayr C, Bartel DP. Widespread shortening of 3’UTRs by alternative cleavage and polyadenylation activates oncogenes in cancer cells. Cell. 2009;138:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandberg R, Neilson JR, Sarma A, Sharp PA, Burge CB. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3’ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science. 2008;320:1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Homa NJ, et al. Epstein-Barr virus induces global changes in cellular mRNA isoform usage that are important for the maintenance of latency. J Virol. 2013;87:12291–12301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02464-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weill L, Belloc E, Bava FA, Mendez R. Translational control by changes in poly(A) tail length: recycling mRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:577–585. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin CL, Evans V, Shen S, Xing Y, Richter JD. The nuclear experience of CPEB: implications for RNA processing and translational control. RNA. 2010;16:338–348. doi: 10.1261/rna.1779810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendez R, et al. Phosphorylation of CPE binding factor by Eg2 regulates translation of c-mos mRNA. Nature. 2000;404:302–307. doi: 10.1038/35005126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendez R, Richter JD. Translational control by CPEB: a means to the end. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:521–529. doi: 10.1038/35080081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox CA, Sheets MD, Wickens MP. Poly(A) addition during maturation of frog oocytes: distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic activities and regulation by the sequence UUUUUAU. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2151–2162. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cepeda V, Esteban M, Fraile-Ramos A. Human cytomegalovirus final envelopment on membranes containing both trans-Golgi network and endosomal markers. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:386–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker JD, Maier CL, Pober JS. Cytomegalovirus-infected human endothelial cells can stimulate allogeneic CD4+ memory T cells by releasing antigenic exosomes. J Immunol. 2009;182:1548–1559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wurdinger T, et al. Extracellular vesicles and their convergence with viral pathways. Adv Virol. 2012;2012:767694. doi: 10.1155/2012/767694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plazolles N, et al. Pivotal advance: The promotion of soluble DC-SIGN release by inflammatory signals and its enhancement of cytomegalovirus-mediated cis-infection of myeloid dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:329–342. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, Smith VL. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:24–43. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burns DM, Richter JD. CPEB regulation of human cellular senescence, energy metabolism, and p53 mRNA translation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3449–3460. doi: 10.1101/gad.1697808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groppo R, Richter JD. CPEB control of NF-kappaB nuclear localization and interleukin-6 production mediates cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2707–2714. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05133-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee YJ, Glaunsinger BA. Aberrant herpesvirus-induced polyadenylation correlates with cellular messenger RNA destruction. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fraile-Ramos A, Cepeda V, Elstak E, van der Sluijs P. Rab27a is required for human cytomegalovirus assembly. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva MC, Yu QC, Enquist L, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus UL99-encoded pp28 is required for the cytoplasmic envelopment of tegument-associated capsids. J Virol. 2003;77:10594–10605. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10594-10605.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanchez V, Sztul E, Britt WJ. Human cytomegalovirus pp28 (UL99) localizes to a cytoplasmic compartment which overlaps the endoplasmic reticulum-golgi-intermediate compartment. J Virol. 2000;74:3842–3851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3842-3851.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomtishen JP., 3rd Human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins (pp65, pp71, pp150, pp28) Virol J. 2012;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu ST, et al. Synaptic vesicle-like lipidome of human cytomegalovirus virions reveals a role for SNARE machinery in virion egress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12869–12874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109796108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albrecht T, Cavallo T, Cole NL, Graves K. Cytomegalovirus: development and progression of cytopathic effects in human cell culture. Lab Invest. 1980;42:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cavallo T, Graves K, Cole NL, Albrecht T. Cytomegalovirus: an ultrastructural study of the morphogenesis of nuclear inclusions in human cell culture. J Gen Virol. 1981;56:97–104. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-56-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 60.Parkhomchuk D, et al. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polymenidou M, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:459–468. doi: 10.1038/nn.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu J, Anczukow O, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ, Zhang C. OLego: fast and sensitive mapping of spliced mRNA-Seq reads using small seeds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5149–5163. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.