Abstract

Background

Distinct behavioral economic domains, including high perceived drug value (demand) and delay discounting (DD), have been implicated in the initiation of drug use and the progression to dependence. However, it is unclear whether frequent marijuana users conform to a “reinforcer pathology” addiction model wherein marijuana demand and DD jointly increase risk for problematic marijuana use and cannabis dependence (CD).

Methods

Participants (n=88, 34% female, 14% cannabis dependent) completed a marijuana purchase task at baseline. A delay discounting task was completed following placebo marijuana cigarette (0% THC) administration during a separate experimental session.

Results

Marijuana demand and DD were quantified using area under the curve (AUC). In multiple regression models, demand uniquely predicted frequency of marijuana use while DD did not. In contrast, DD uniquely predicted CD symptom count while demand did not. There were no significant interactions between demand and DD in either model.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that frequent marijuana users exhibit key constituents of the reinforcer pathology model: high marijuana demand and steep discounting of delayed rewards. However, demand and DD appear to be independent rather than synergistic risk factors for elevated marijuana use and risk for progression to CD. Findings also provide support for using AUC as a singular marijuana demand metric, particularly when also examining other behavioral economic constructs that apply similar statistical approaches, such as DD, to support analytic methodological convergence.

Keywords: marijuana, behavioral economics, cannabis dependence, purchase task, area under the curve, delay discounting

1. INTRODUCTION

Ease of accessibility to inexpensive marijuana may be a substantial risk factor for elevated use, similar to risk factors that have been linked with excessive alcohol consumption (Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). As initiation and use of marijuana increase, there will be a concomitant increase in the number of individuals who develop cannabis use disorder (CUD). It is imperative that salient predictors of CUD and level of use be identified in the wake of the normative and legal shift concerning marijuana.

The propensity to initiate and maintain substance use has been linked with impulsivity (de Wit, 2009; Guy et al., 1994). Elevated impulsivity is characterized by poor decision making and diminished ability to foresee and evaluate negative consequences (Adinoff et al., 2007). Impulsivity is a complex and multi-faceted behavioral domain (Courtney et al., 2012; Cyders and Coskunpinar, 2011; Stahl et al., 2014), however, key components of impulsivity can be captured via the examination of precise behavioral constructs. Delay discounting (DD), characterized by deficits in self-regulation, is one such measure of impulsivity, and fits into a framework of behavioral economic processes. Behavioral economics is ideally suited to the conceptualization of the progression of substance use and dependence as it endeavors to integrate internal processes operating within a substance user with external factors and influences in the environment (Bickel et al., 2014). In addition, substance demand, characterized by perceived drug value, is a related behavioral economic process that may putatively facilitate understanding of initiation and maintenance of substance use.

DD paradigms reveal an individual's intertemporal reward preference profile, namely, their preferred choice with respect to the conflict between smaller rewards obtainable in the short-term (e.g., drug of choice), set against larger or superior rewards accessible at a given future time (e.g., future positive life outcomes; MacKillop, 2013). With regard to substance use, the inability to perceive increased value in superior future rewards may explain loss of control over drug use, a key element of drug dependence (Bickel and Marsch, 2001). Consequently, substance users frequently disregard previously set limits when the prospect to use a preferred substance arises. It has been consistently shown that substance use disorders tend to be significantly related to steep DD processes (MacKillop et al., 2011). Individuals with an array of addictive disorders display significantly greater discounting for preferred substances including tobacco (Johnson et al., 2007) and alcohol (Petry, 2001), as compared to control groups.

Compared to other frequently misused substances, the relationships among DD, level of marijuana use, and the presence of CUD have been less clear. Johnson et al. (2010) investigated DD among marijuana-dependent individuals and control participants and found no significant difference in discounting, but did report a trend toward elevated discounting in the marijuana-dependent group. Furthermore, among college students, participants’ age at first marijuana use has been negatively correlated with DD, with earlier onset of marijuana use being related to elevated DD (Kollins, 2003). Acute administration of delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive constituent of marijuana, to marijuana users produced no significant effects on DD (McDonald et al., 2003; Metrik et al., 2012). Consequently, more research is required to determine whether a relationship between marijuana use and DD exists.

Substance demand, or the perceived value of a given drug, can be assessed by examining performance on a drug purchase task. Demand is the quantitative relationship between use and cost (Hursh et al., 2005). Participants indicate how much they would be willing to pay for their preferred drug at increasing levels of price. Laboratory models permit assessment of several behavioral economic substance demand indices, including intensity (substance amount consumed at zero cost), Pmax (price at maximum expenditure), Omax (total peak expenditure), breakpoint (cost whereby consumption is suppressed to zero), and elasticity of demand (rate at which consumption decreases as price increases). Studies consistently confirm the existence of significant relationships between indices of drug demand and substance use disorders. For example, indices of tobacco cigarette demand have been linked with increased nicotine dependence (Chase et al., 2013; MacKillop et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2011), and alcohol demand metrics have been significantly related to alcohol problem severity and level of alcohol consumption (MacKillop et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2009; Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). Furthermore, indices of marijuana demand have been related to cannabis dependence (CD) symptom count and self-reported marijuana craving (Aston et al., 2015), as well as level of use (Aston et al., 2015; Collins et al., 2014) and cue-elicited craving (Metrik et al., 2016).

Substance demand can be characterized by five distinct behavioral economic indices, but moderate to high correlations among indices are common. Furthermore, while each demand index explains a unique facet of the drug's individualized perceived value, it may be problematic from a statistical perspective to include all five metrics in the same formal analysis due to potential for Type I error and multicollinearity (Amlung et al., 2015). To address this, Amlung et al. (2015) successfully employed an area under the curve (AUC) analysis to calculate an index of demand for the alcohol purchase task, generating a single metric that was significantly correlated with the individual focal indices. AUC may be particularly advantageous in the analysis of relative drug value because it incorporates the full volume of reported demand, in essence, integrating all metrics. Moreover, utilizing AUC to represent substance demand allows for clear methodological convergence with the DD literature wherein AUC is used to capture DD performance (Amlung et al., 2015).

Standardization of measurement and analytic approaches facilitates comparability of data across studies and enables replication of findings. In this regard, convergence in analytic methodology in behavioral economics is particularly significant as a central priority is improved understanding of the distinct and dual influences of DD and substance demand within a conceptualization of addiction known as “reinforcer pathology” (Bickel et al., 2014, 2011). Reinforcer pathology is defined as the joint effects of two constituent processes: (a) the persistently high valuation of a reinforcer (i.e., demand), and/or (b) the excessive preference for the immediate acquisition or consumption of a commodity despite long-term negative outcomes (i.e., DD; Bickel et al., 2014, 2011). Behavioral economics has suggested that individuals with substance use disorders may consistently experience an interplay between demand and DD, specifically by exhibiting high personal valuation of their preferred substance while also displaying a preference toward receiving and using it immediately. Moreover, it has been posited that these two processes may synergistically interact to contribute to reinforcer pathology (Bickel et al., 2011).

While the interplay between substance demand and discounting may be of chief importance (Bickel et al., 2011), the presence of a relationship between these two behavioral economic constructs in the literature has been equivocal, and it has yet to be determined whether these are related or independent components of the reinforcer pathology conceptualization of addiction. Elevated levels of substance demand and DD are posited to be recurrent etiological markers in the progression of drug use and the development of substance use disorders (Bickel et al., 2014). In this regard, a study conducted by MacKillop and colleagues (2010) concluded that both high demand for alcohol and elevated DD were associated with increased alcohol use disorder severity. While demand and DD are purported to be correlated with severity of dependence, the relationship between substance demand and DD is unclear. Teeters et al. (2015) found no bivariate relationship between indices of alcohol demand and DD in a study evaluating the relationships among demand, discounting, and driving after drinking. Furthermore, Amlung and colleagues (2013) also found no bivariate relationship between demand and discounting in a study examining alcohol demand and impulsivity in the context of combined alcohol and caffeine consumption. MacKillop and Tidey (2011) investigated demand for tobacco cigarettes and DD in a study examining nicotine dependence among smokers with schizophrenia. The schizophrenia group significantly differed from the control group with respect to demand for cigarettes, however, there were no group differences in DD. Moreover, the association between marijuana demand and DD has not yet been investigated. Further research is necessary to evaluate the theoretical premise of reinforcer pathology in the progression and maintenance of substance use disorders.

In the current study, we sought to test whether frequent marijuana users conform to a reinforcer pathology model of addiction by examining the joint influence of marijuana demand and DD. We also sought to examine potential interactions between marijuana demand and DD to determine whether these variables display synergistic or additive roles in contributing to elevated marijuana use and dependence symptoms. In addition, we examined the relationship between DD and marijuana demand by assessing the bivariate relationship between demand as assessed by an AUC analysis and DD, as well as demand for marijuana and DD in relation to marijuana use and CD symptoms. We hypothesized that demand and DD would be significantly correlated with one another and would jointly contribute to elevated marijuana use and dependence symptoms in support of the reinforcer pathology framework. Furthermore, we hypothesized that demand and DD would interact to synergistically contribute to problematic marijuana use.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Data were obtained from participants who completed an experimental study investigating variability in marijuana's acute and cue-elicited effects (Metrik et al., 2016). Participants were 88 non-treatment seeking frequent marijuana users recruited through newspaper advertisements, flyers, and social media websites who met the following inclusion criteria: native English speakers, 18–44 years of age, non-Hispanic Caucasian (due to genetic aims of the parent study), marijuana use at least 2 days per week in the past month and at least weekly in the past 6 months, and self-reported ability to abstain from marijuana for 24 hours without withdrawal. Exclusion criteria were: intent to quit or receive treatment for cannabis abuse, positive urine toxicology test result for drugs other than marijuana, pregnancy, nursing, past month affective or panic disorder, psychotic or suicidal state assessed by psychiatric interview, contraindicated medical issues assessed by physical exam, body mass index > 30, and smoking more than 20 tobacco cigarettes per day. Five participants showed evidence of low effort on the MPT (e.g., inconsistent responding across prices) and were excluded from subsequent analysis (Aston et al., 2015). The final sample included 83 participants (35% female). Positive THC urine screens were obtained from 83% of participants. Furthermore, 14.5% of the sample met criteria for past year DSM-IV CD, endorsing a mean of 1.2 (SD=1.3) symptoms. The median reported family income bracket was $60,000-69,999 annually.

2.2 Procedure

Full details of procedures used in the current study have been previously described (Metrik et al., 2016), however, pertinent procedural details are included here. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brown University. Participants completed a baseline session followed by two experimental sessions during which they smoked either active or placebo marijuana. All data for the current study were drawn from the parent study's baseline session, with the exception of a DD task, which was administered after participants smoked a placebo marijuana cigarette. Participants were compensated upon study completion.

2.3 Measures

DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses were determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Non-Patient Edition (SCID; First et al., 2002). The Time-Line Follow-Back Interview (TLFB; Dennis et al., 2004) was used to assess number of marijuana use days over the past 60-days. The Delay Discounting Task (DDT) used a computerized adjusting-amount procedure to measure discounting of delayed monetary reinforcers (Richards et al., 1999). In a series of choice trials, participants were offered the hypothetical choice between $10 available after a delay (0, 2, 30, 180, and 365 days) or a smaller amount available immediately. The dependent variable was AUC connecting indifference points and the x-axis, from 0.0 (steepest discounting) to 1.0 (no discounting; Myerson et al., 2001). The Marijuana Purchase Task (MPT) assessed behavioral economic marijuana demand via measurement of marijuana purchase at escalating units of price (Aston et al., 2015). The MPT assesses how many marijuana hits one would smoke at 22 prices ($0 to $10 per hit). Participants were asked to respond to items as if it were a typical marijuana use day and were informed that the marijuana available for purchase was of average quality.

2.4 Data Analysis Plan

Five metrics of marijuana demand were obtained from the MPT: (a) intensity of demand (i.e., the amount of drug consumed at zero cost; capped at 99 hits), (b) Omax (i.e., peak expenditure for a drug), (c) Pmax (i.e., price at maximum expenditure), (d) breakpoint (i.e., cost at which consumption is suppressed to zero), and (e) elasticity of demand (i.e., the sensitivity of marijuana consumption to increases in cost). Calculations of demand indices were obtained using the following methods. Price elasticity was generated using the following nonlinear exponential demand curve model (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008): log10Q = log10Q0 + k(e−αQ0C-1), where Q=quantity consumed, Q0=derived intensity, k=a constant across individuals that denotes the range of the dependent variable (marijuana hits) in logarithmic units, C=the cost of the commodity, and α=elasticity or the rate constant determining the rate of decline in log consumption based on increases in price (i.e., essential value). The overall best-fitting k parameter was determined to be 2. An R2 value was generated to reflect percentage of variance accounted for by the demand equation (i.e., the adequacy of the fit of the model to the data). Consistent with procedures employed by Jacobs and Bickel (1999), when fitting the data to the demand equation, breakpoint consumption was coded as an arbitrarily nonzero value of 0.1 to provide an x-axis intercept of the demand curve that was amenable to logarithmic transformation. Similarly, the initial price (i.e., marijuana at zero cost) was replaced by a value of one cent ($.01) to permit the use of the logarithmic transformation in the demand curve model.

MPT-AUC values were calculated for consumption curves. The total area was operationalized as the AUC value when the maximum consumption value across the entire sample was input at each price. For this sample, the maximum number of marijuana hits purchased across all prices was 90. Therefore, total AUC was calculated by generating a demand curve with 90 at each of the 21 price intervals. Proportionate AUC values (ranging from 0.0 to 1.0) were then generated by dividing each participant's raw AUC value by the total AUC. Higher AUC values reflect greater marijuana demand. Following the calculation of all demand metrics and AUC, each was examined for adequacy of distribution and outliers. Skewed variables were transformed to improve distribution.

DD-AUC was calculated using the following methods proposed by Myerson and colleagues (2001). First, the delay and subjective value for each data point was normalized. The delay was expressed as a proportion of the maximum delay, and the subjective value was expressed as a proportion of the nominal amount (i.e., the subjective value divided by the actual, delayed amount). These normalized values were used as x coordinates and y coordinates and used to construct a graph of the discounting data for each participant. Vertical lines were drawn from each data point to the x axis, subdividing the graph into a series of trapezoids. The area of each trapezoid was calculated using the following formula (x2 - x1)[(y1 + y2)/2], wherein x1 and x2 are successive delays, and y1 and y2 are the subjective values associated with these delays. For the first trapezoid, the value of x1 and y1 were defined as 0.0 and 1.0. The total AUC was obtained by summing the areas of the trapezoids. The steeper the discounting (i.e., the lower the subjective value of delayed rewards), the smaller the AUC. Because the x and y values were normalized, the AUC varied between 0.0 (steepest possible discounting) and 1.0 (no discounting).

Pearson product-moment correlations were used to examine bivariate relationships among MPT-AUC, DD, number of current DSM-IV CD symptoms (CD symptom count), total tobacco cigarettes smoked over the past 60 days (tobacco use), age, and household income. Correlations among traditional demand indices and MPT-AUC were also examined. Two separate multiple regression models were used to examine the impact of marijuana demand and DD on CD symptom count and frequency of marijuana use (percent of days when marijuana was used in the past 60 days). To limit inclusion of multiple demand variables in models and to support methodological convergence in the analysis of behavioral economic constructs, MPTAUC was included in both models as a single representative variable for level of marijuana demand. Household income, tobacco use, age, and sex were included as covariates in both models. Finally, the interaction between marijuana demand and DD was examined for evidence of a potential synergistic relationship. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and GraphPad Prism 7.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

Demographic, marijuana use, and demand variables are presented in Table 1. Raw MPT data were examined for outliers using standard scores, with a criterion of Z = 3.29 (p < 0.001) to retain maximum data. A small number of outliers were detected (46/1826 data points; 2.5%). The outliers were determined to be legitimate high-magnitude values and were recoded as one unit higher than the next lowest non-outlying value (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2000). All data were examined for distribution normality. A square root transformation was applied to CD symptom count and breakpoint. A logarithmic transformation was applied to tobacco use, Omax, intensity, and Pmax. A cube root transformation was applied to elasticity and MPT-AUC. Transformations improved variable distribution substantially.

Table 1.

Demographics and descriptive variables

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 29 (35) |

| Male | 54 (65) |

| Age at initiation of regular marijuana use | |

| Below 17 | 29 (35) |

| 17 or older | 54 (65) |

| Marijuana ounces used per week | |

| Less than 1/16th | 9 (11) |

| 1/16th | 19 (23) |

| 1/8th | 25 (30) |

| 1/4th | 13 (16) |

| More than 1/4th | 17 (20) |

| Any tobacco use past 60 days | 40 (48) |

| Household Income | |

| $0 – 19,999 | 21 (25) |

| $20,000 – 39,999 | 6 (7) |

| $40,000 – 59,999 | 8 (10) |

| $60,000 – 79,999 | 18 (22) |

| $80,000 and above | 30 (36) |

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

| Age | 21.6 (4.7) |

| Percent marijuana use days past 60 days | 72.0 (22.3) |

| Number of times used marijuana on average day | 2.1 (1.3) |

| Tobacco Use (n = 40) | |

| Number tobacco cigarettes smoked past 60 days | 184.3 (242.2) |

| Percent tobacco use days | 56.8 (41.8) |

| Number tobacco cigarettes smoked per day | 4.1 (3.9) |

| Demand Metric | |

| Intensity | 24.94 (30.30) |

| O max | 16.03 (25.48) |

| P max | 2.31 (2.12) |

| Breakpoint | 4.27 (3.12) |

| Elasticity | 0.05 (0.04) |

| MPT-AUC | 0.03 (0.05) |

| DDT-AUC | 0.57 (0.27) |

| DDT Indifference Points | |

| Delay 1: 0 days | 9.21 (0.77) |

| Delay 2: 2 days | 8.68 (1.10) |

| Delay 3: 30 days | 6.81 (2.61) |

| Delay 4: 180 days | 5.40 (3.03) |

| Delay 5: 365 days | 4.84 (3.10) |

Note. DDT-AUC = Delay Discounting Task Area Under the Curve; MPT-AUC = Marijuana Purchase Task Area Under the Curve.

3.2 Marijuana Purchase Task

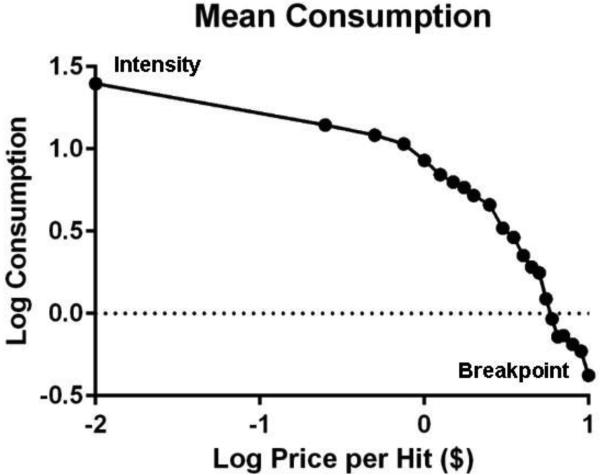

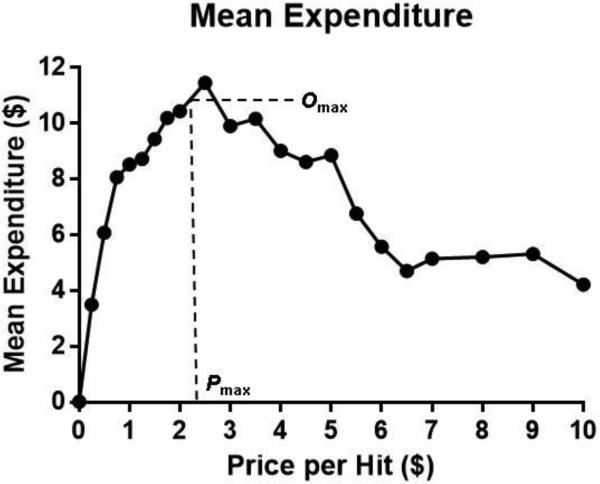

Demand and expenditure curves from the MPT were prototypical. Specifically, MPT consumption decreased with increasing price (Figure 1); MPT expenditure initially increased and ultimately decreased with rising price (Figure 2). The exponential demand equation provided an excellent fit to the overall demand data (R2 = 0.99) and a very good fit to the individual data (median R2 = 0.82, interquartile range = 0.75 - 0.86).

Figure 1.

Demand curve for consumption of marijuana hits. The x-axis provides log-transformed price in dollars ($) and the y-axis provides log-transformed self-reported consumption in marijuana hits.

Figure 2.

Expenditure curve for purchase of marijuana hits. The x-axis provides price in dollars ($) and the y-axis provides expenditure in dollars ($). Values are presented in actual units rather than conventional logarithmic units for interpretational clarity.

3.3 Bivariate Correlations

Bivariate correlations among key variables are presented in Table 2. MPT-AUC was positively related to marijuana use frequency and tobacco use. CD symptom count was positively correlated with marijuana use frequency and negatively correlated with DDT. Marijuana use frequency was significantly correlated with tobacco use. Bivariate correlations among traditional demand indices and MPT-AUC are presented in Table 3. All demand metrics were correlated with one another, with the exception of Pmax and intensity. MPT-AUC was significantly correlated with all five demand indices, indicating that AUC may be a robust representative variable for demand.

Table 2.

Variable intercorrelations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CD Symptom Count | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. % Marijuana Use Days | .33** | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. DDT | −.28* | −.08 | - | - | - | - |

| 4. MPT-AUC | .19 | .31** | −.16 | - | - | - |

| 5. Household Income | −.00 | −.20 | .08 | .09 | - | - |

| 6. Age | −.21 | .00 | .09 | −.12 | −.34** | - |

| 7. Tobacco Use | −.02 | .33** | .01 | .34** | −.20 | .01 |

Note. CD Symptom Count = DSM-IV Cannabis Dependence Symptom Count; % Marijuana Use Days = Percent days when marijuana was used over the past 60 days; DDT = Delay Discounting Task; MPT-AUC = Marijuana Purchase Task Area Under the Curve; Tobacco Use = total number of cigarettes smoked over the past 60 days. A square root transformation was applied to DSM-IV Cannabis Dependence Symptom Count. A cube root transformation was applied to MPT-AUC. A logarithmic transformation was applied to Tobacco Use.

***p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Table 3.

Intercorrelations among marijuana demand indices

| Index | Intensity | P max | O max | Breakpoint | Elasticity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | - | - | - | - | |

| P max | −.04 | - | - | - | |

| O max | .45*** | .54*** | - | - | |

| Breakpoint | .24* | .81*** | .74*** | - | |

| Elasticity | −.38*** | −.72*** | −.87*** | −.93*** | |

| MPT-AUC | .65*** | .46*** | .93*** | .74*** | −.86*** |

Note. MPT-AUC = Marijuana Purchase Task Area Under the Curve. A square root transformation was applied to breakpoint. A cube root transformation was applied to elasticity and MPT-AUC. A logarithmic transformation was applied to Omax, intensity, and Pmax.

p<0.001

**p<0.01

p<0.05

3.4 Multiple Regression Models

Results from the two multiple regression models examining the effect of marijuana demand and DD on CD symptom count and marijuana use frequency are presented in Table 4. In the model examining the impact of marijuana demand (MPT-AUC) and DD on CD symptom count, there was a significant main effect of DD (sr2 = 0.05, p = 0.04), but not marijuana demand. In the model examining the impact of marijuana demand and DD on marijuana use frequency, there was a significant main effect of marijuana demand (sr2 = 0.05, p = 0.04), but no effect of DD. The interaction between marijuana demand and DD was not significant in either model (ps > 0.4), thus models without the inclusion of the demand x DD interaction term are presented.

Table 4.

Multiple regression models predicting cannabis dependence symptom count and marijuana use frequency

|

DSM-IV Cannabis Dependence Symptom Count (n=83) (F(6,76) = 2.32, R2 = 0.15; p = 0.04) | ||||||

| Predictors | B | β | SE | 95% CI | p Value | sr2 |

| MPT-AUC | 1.27 | 0.20 | 0.76 | −0.24 – 2.79 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| DDT | −0.62 | −0.23 | 0.29 | −1.20 – −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Household Income | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.06 – 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.00 |

| Tobacco Use | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.09 – 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.00 |

| Age | −0.03 | −0.19 | 0.02 | −0.06 – 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| Sex | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.17 | −0.13 – 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.02 |

|

Percent Marijuana Use Days Past 60 Days (n=83) (F(6,76) = 2.90, R2 = 0.19; p = 0.01) | ||||||

| Predictors | B | β | SE | 95% CI | p Value | sr2 |

| MPT-AUC | 48.54 | 0.24 | 23.21 | 2.31 – 94.77 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| DDT | −1.61 | −0.02 | 8.87 | −19.27 – 16.05 | 0.86 | 0.00 |

| Household Income | −1.22 | −0.20 | 0.71 | −2.64 – 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| Tobacco Use | 1.84 | 0.20 | 1.06 | −0.26 – 3.94 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Age | −0.17 | −0.04 | 0.53 | −1.24 – 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.00 |

| Sex | −1.96 | −0.04 | 5.09 | −12.10 – 8.18 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

Note. DDT = Delay Discounting Task; MPT-AUC = Marijuana Purchase Task Area Under the Curve/ A square root transformation was applied to DSM-IV Cannabis Dependence Symptom Count. A cube root transformation was applied to MPT-AUC. A logarithmic transformation was applied to Tobacco Use. Bold indicates statistical significance.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first study to assess the relationship between marijuana demand and DD in frequent marijuana users. We aimed to clarify the relationship between demand and discounting, and also examined the ability of these variables to predict key markers of problematic marijuana consumption, namely CD symptom count and frequency of marijuana use. In addition, this is the first study to evaluate evidence for a reinforcer pathology model for problematic marijuana use and dependence using a behavioral economic framework. Furthermore, to increase methodological convergence with DD analyses, we employed a novel analytic method for quantification of marijuana demand using an AUC analysis.

Demand and DD are posited to jointly contribute to the reinforcer pathology that typifies substance use disorders (Bickel et al., 2014). In this regard, one clear advantage of an AUC approach to quantifying demand is that it allows for calculation of a common metric that can be used in research investigating the combined impact of demand and DD on substance misuse. In the current study, AUC was successfully used as a single representative index reflecting demand for marijuana, ultimately allowing for methodological convergence with other behavioral economic domains that support use of AUC as an analytic approach, namely, DD (Amlung et al., 2015; Myerson et al., 2001).

In the multiple regression analysis examining predictors of CD symptom count, DD predicted CD symptom count while demand did not. MacKillop and colleagues (2010) found that among drinkers, DD was significantly related to alcohol use disorder symptom count. The processes underlying DD are theorized to be the foundation for the preference reversal from abstinence to alcohol consumption frequently observed among individuals with alcohol use disorders in treatment (MacKillop et al., 2010). While individual demand indices have been associated with cannabis dependence symptom count (Aston et al., 2015), when DD was included in the model with MPT-AUC simultaneously, DD exerted a stronger influence on problematic substance use.

In the multiple regression model predicting frequency of marijuana use, demand predicted marijuana use frequency while DD was not a significant predictor. Substance demand often exhibits a significant relationship with level of substance use and use frequency (Amlung et al., 2015; Collins et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2013). In the current multivariate analysis, demand predicted marijuana use frequency, overshadowing any predictive ability of DD. While both demand and DD tap unique and distinct components of behavioral choice, certain demand indices, specifically intensity and Omax, have been significantly correlated with marijuana use frequency (Aston et al., 2015) and level of alcohol use (Mackillop et al., 2009). Thus it is plausible that demand is highly linked with preferences for volumetric drug consumption (Mackillop et al., 2009), and therefore is strongly predictive of level of substance use. DD is not always related to level of substance use (MacKillop et al., 2010), and is more commonly associated with problematic substance use and other addiction pathology. This may be explained by demand reflecting hypothetical choices that will happen immediately and are thus related to instantaneous use, while DD reflects choices that may impact future outcomes such as dependence symptoms and more distant problems (Bickel et al., 2014).

The present research did not detect a significant interaction between marijuana demand and DD. Evidence in the literature for a synergistic relationship between substance demand and discounting has been mixed, with some research indicating that these two behavioral economic domains tap very different components of behavioral choice and decision-making. With respect to frequent marijuana users, it appears that demand and discounting play unique and clearly separate roles when used to predict important markers of problematic marijuana use, ultimately capturing unique decision-making processes. As a similar statistical analysis technique, AUC, was used to analyze marijuana demand and DD in this sample, we can conclude with additional certainty that these domains are separate, unique behavioral economic components. Moreover, demand and discounting each predicted separate variables that comprise problematic marijuana use (i.e., frequency of marijuana use and CD dependence symptoms), thus while these variables do not synergistically increase risk for potentially harmful marijuana use, demand and discounting appear to jointly contribute to the reinforcer pathology conceptualization of addiction.

4.1 Limitations

While this study makes an important contribution to the literature regarding the reinforcer pathology framework and its applications to frequent marijuana users, certain limitations should be noted. This study was cross-sectional therefore we cannot make assumptions about causal relationships among DD, demand, marijuana use frequency, and CD. Furthermore, due to the small number of marijuana users with CD, results may not generalize to other samples with higher CD rates. In addition, DD was assessed after placebo marijuana administration, therefore expectancies may have influenced performance (Metrik et al., 2009). Because the current sample was exclusively Caucasian due to genetic aims of the parent study, results may not generalize to racially diverse samples of marijuana users. Additionally, IQ was not measured in the current study, thus conclusions regarding the impact of intelligence on marijuana demand and DD could not be assessed. The marijuana available for purchase in the MPT was described as “average quality.” It is possible that specification of average quality marijuana impacted demand among this sample as has been recently shown in other research (Collins et al., 2016). Finally, in an effort to capture the smallest unit of marijuana administration across disparate modes, marijuana hits were employed as the unit of purchase on the MPT (Aston et al., 2015). However, marijuana is generally purchased in units of weight, such as grams or ounces, therefore, weight may align more effectively with purchasing behavior. Additional research in this area is essential for improving knowledge regarding common modes of marijuana administration, units of purchase, and appropriate unit of measure for administration (e.g., hits, joints, ounces), and can properly inform MPT development. Ongoing qualitative research in our laboratory was designed to assess these variables and will help clarify the optimal unit of purchase to incorporate in subsequent MPT studies.

4.2 Conclusions

Though demand and DD do not appear to exhibit a synergistic relationship with respect to marijuana use, pharmacological and behavioral treatments targeted at altering these behavioral economic domains still have the propensity to improve treatment response and may reduce the risk for relapse. A pharmacological approach to treating substance use disorders may reduce demand by alleviating symptoms of withdrawal, diminishing craving, substituting for the given drug, or may impose a high cost on the individual via causing physical discomfort, illness, or penalty when the drug is used. Similarly, manipulations such as behavioral contracts and fading procedures may be useful in impacting DD behavior (Bickel et al., 2014). Future research should continue to use a reinforcer pathology framework within other misused substances, with a focus toward achieving methodological convergence in statistical analysis approach via utilization of an AUC approach across behavioral economic domains.

Highlights.

This study was designed to test the reinforcer pathology model of addictive behavior.

Demand and Delay Discounting (DD) do not exhibit a synergistic relationship with respect to marijuana.

Demand and DD are independent risk factors for problematic marijuana use.

Findings provide support for using area under the curve (AUC) as a singular marijuana demand metric.

Acknowledgements

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this research was supported by NIDA grant R03DA027484 to Drs. Metrik and Knopik. Manuscript preparation and data analysis was supported by NIH grants 2T32AA007459 and K01DA039311 (Dr. Aston). Dr. MacKillop is the holder of the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research, which partially supported his contributions, and Dr. Amlung's contributions were supported by the Peter Boris Centre for Addictions Research. Funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, data analysis or interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Dr. Metrik conducted the study from which these data were obtained. Drs. Aston, MacKillop, and Amlung conducted the statistical analyses. Dr. Aston wrote the manuscript and all authors edited the manuscript together. All authors significantly contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Author Disclosure

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no personal or financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adinoff B, Rilling LM, Williams MJ, Schreffler E, Schepis TS, Rosvall T, Rao U. Impulsivity, neural deficits, and the addictions: the “oops” factor in relapse. J. Addict. Dis. 2007;26:25–39. doi: 10.1300/J069v26S01_04. doi:10.1300/J069v26S01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Few LR, Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Metrik J, MacKillop J. Impulsivity and alcohol demand in relation to combined alcohol and caffeine use. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:467–474. doi: 10.1037/a0034214. doi:10.1037/a0034214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Yurasek A, McCarty KN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. Area under the curve as a novel metric of behavioral economic demand for alcohol. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015;23:168–175. doi: 10.1037/pha0000014. doi:10.1037/pha0000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston ER, Metrik J, MacKillop J. Further validation of a marijuana purchase task. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.025. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Gatchalian KM. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: implications for etiology and treatment of addiction. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:406–415. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1. doi:10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014;10:641–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase HW, Mackillop J, Hogarth L. Isolating behavioural economic indices of demand in relation to nicotine dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2013;226:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2911-x. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Vincent PC, Earleywine M, Liu L, Yu J, de Leo J. The Effects Of Perceived Quality On Demand For Marijuana: Policy Implications Of A Web-Based Behavioral Economic Experiment With Young-Adult Marijuana Users.. Presented at the Marijuana and Cannabinoids: A Neuroscience Research Summit; NIH Campus, Bethesda, MD.. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Vincent PC, Yu J, Liu L, Epstein LH. A behavioral economic approach to assessing demand for marijuana. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035318. doi:10.1037/a0035318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KE, Arellano R, Barkley-Levenson E, Gálvan A, Poldrack RA, Mackillop J, Jentsch JD, Ray LA. The relationship between measures of impulsivity and alcohol misuse: an integrative structural equation modeling approach. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36:923–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01635.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A. Measurement of constructs using self-report and behavioral lab tasks: is there overlap in nomothetic span and construct representation for impulsivity? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011;31:965–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict. Biol. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Funk R, Godley SH, Godley MD, Waldron H. Cross-validation of the alcohol and cannabis use measures in the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) and Timeline Followback (TLFB; Form 90) among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 99 Suppl. 2004;2:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00859.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Biometrics Research. New York: 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IVTR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP). [Google Scholar]

- Guy SM, Smith GM, Bentler PM. Consequences of adolescent drug use and personality factors on adult drug use. J. Drug Educ. 1994;24:109–132. doi: 10.2190/X4WU-BV3X-Q483-Y5BT. doi:10.2190/X4WUBV3X-Q483-Y5BT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Galuska CM, Winger G, Woods JH. The economics of drug abuse: a quantitative assessment of drug demand. Mol. Interv. 2005;5:20–28. doi: 10.1124/mi.5.1.6. doi:10.1124/mi.5.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol. Rev. 2008;115:186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Bickel WK. Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:412–426. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F. Moderate drug use and delay discounting: a comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:187–194. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F, Moore BA, Badger GJ, Budney AJ. Delay discounting in current and former marijuana-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:99–107. doi: 10.1037/a0018333. doi:10.1037/a0018333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH. Delay discounting is associated with substance use in college students. Addict. Behav. 2003;28:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00220-4. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J. Integrating behavioral economics and behavioral genetics: delayed reward discounting as an endophenotype for addictive disorders. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2013;99:14–31. doi: 10.1002/jeab.4. doi:10.1002/jeab.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2011;216:305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010;119:106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. doi:10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Eisenberg DTA, Lisman SA, Lum JK, Wilson DS. Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:57–65. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.1.57. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Bickel WK. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2009;203:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Tidey JW. Cigarette demand and delayed reward discounting in nicotine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia and controls: an initial study. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2011;216:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2185-8. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2185-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J, Schleifer L, Richards JB, de Wit H. Effects of THC on behavioral measures of impulsivity in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1356–1365. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300176. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, Aston ER, Kahler CW, Rohsenow DJ, McGeary JE, Knopik VS, MacKillop J. Cue-elicited increases in incentive salience for marijuana: craving, demand, and attentional bias. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.027. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, Kahler CW, Reynolds B, McGeary JE, Monti PM, Haney M, de Wit H, Rohsenow DJ. Balanced placebo design with marijuana: pharmacological and expectancy effects on impulsivity and risk taking. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2012;223:489–499. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2740-y. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2740-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, McGeary J, Cook TAR, de Wit H, Haney M, Kahler CW. Effectiveness of a marijuana expectancy manipulation: piloting the balanced-placebo design for marijuana. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:217–225. doi: 10.1037/a0016502. doi:10.1037/a0016502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. doi:10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Tidey JW, Brazil LA, Colby SM. Validity of a demand curve measure of nicotine reinforcement with adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, McDevitt-Murphy ME, MacKillop J, Martens MP. Symptoms of depression and PTSD are associated with elevated alcohol demand. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.022. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. doi:10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. doi:10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 1999;71:121–143. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121. doi:10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl C, Voss A, Schmitz F, Nuszbaum M, Tüscher O, Lieb K, Klauer KC. Behavioral components of impulsivity. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014;143:850–886. doi: 10.1037/a0033981. doi:10.1037/a0033981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th edition. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of driving after drinking among college drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015;39:896–904. doi: 10.1111/acer.12695. doi:10.1111/acer.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]