Abstract

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome caused by group B streptococcus (GBS) is a rare, but lethal disease. We experienced a 45-year-old woman with pustular psoriasis who developed toxic shock-like syndrome during infliximab treatment. Surprisingly, similar episodes recurred three times in one year with restarting of infliximab treatments. In the third episode, GBS were detected in blood, urine, and vaginal secretion cultures. These episodes of shock syndrome were possibly due to GBS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of recurrent streptococcal toxic shock syndrome possibly caused by GBS which was induced by anti-TNF-α inhibitor therapy. The restarting of biological agents in patients with a history of toxic shock syndrome should therefore be avoided as much as possible.

Keywords: streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, recurrent, tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor, infliximab, Streptococcus agalactiae

Introduction

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is an acute, systemic, toxin-mediated illness that typically results in shock and multi-organ failure (1). It is usually caused by toxin-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus. In the early 1980s, the use of highly absorbent tampons was associated with the occurrence of TSS. From 1990s, the incidence of menstrual TSS has decreased, while that of nonmenstrual TSS has increased (2).

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) due to Streptococcus pyogenes was first described by Bohach et al. in 1990 (3). Group B streptococcus (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae) is a major pathogen of neonatal sepsis and meningitis. It is also an important pathogen of invasive bacterial infections in nonpregnant adults (4). A Denmark surveillance study reported that GBS-related STSS comprised about 9% of all cases caused by Streptococcus (5).

Recurrent menstrual TSS is a well-described phenomenon caused by persistent colonization with a toxigenic S. aureus strain and persistent neutralizing antibodies. However, recurrent nonmenstrual TSS is rare for reasons that have yet to be elucidated (6). No report has described recurrent STSS due to S. agalactiae. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors can lead to lower respiratory infections, skin/soft tissue infections, and sepsis (7). However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no report of recurrent TSS or STSS caused by TNF-α inhibitors.

We herein report a case of recurrent TSS possibly caused by S. agalactiae triggered by TNF-α inhibitors.

Case Report

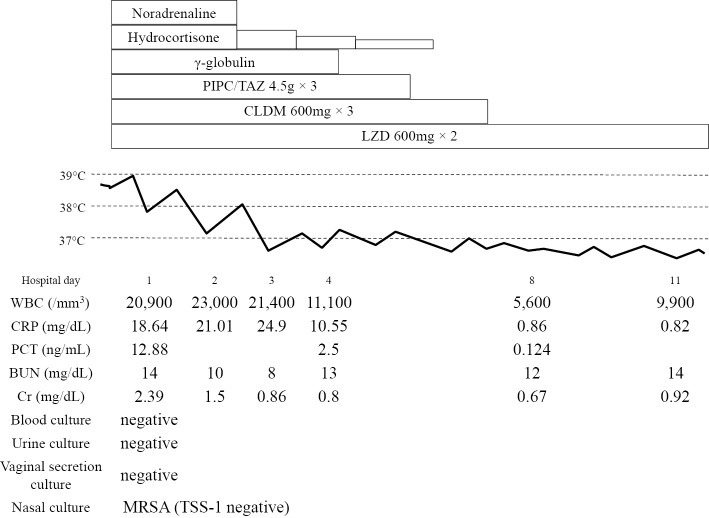

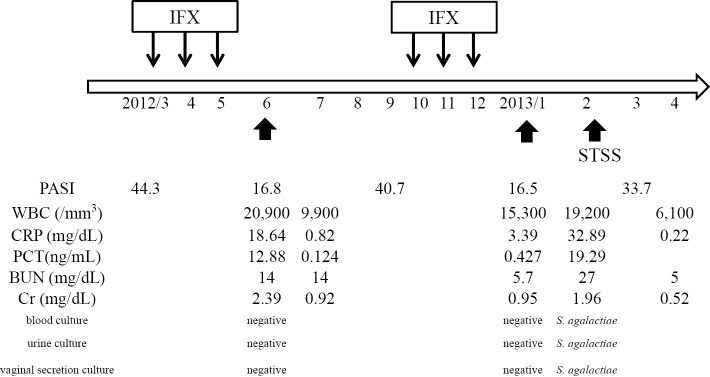

A 45-year-old woman who had cutaneous symptoms of severe pustular psoriasis for more than 30 years was first induced with infliximab (IFX) in March 2012, and received three doses. Following induction, her skin condition dramatically improved. However, she visited the general hospital for a high fever and frequent watery diarrhea on June 2012. She was in shock and an oliguric state and was referred to our hospital. Her body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation were 38.9°C, 77/51 mmHg, 118 bpm, and 98% on room air, respectively. Scales due to psoriasis and diffuse macular erythroderma were observed. However, the site of cutaneous infection was not observed. Laboratory tests showed an elevated white blood cell count (20,900/mm3) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (18.64 mg/dL), procalcitonin (12.88 ng/mL), and serum creatinine (2.39 mg/dL) levels. No white blood cells or bacteria were observed in urine sediments. Chest and abdominal computed tomography found no focus of infection. Blood, urine, and vaginal secretion cultures were negative. A nasal swab culture revealed methicillin-resistant S. aureus; however, it was negative for TSS-1 toxin production. We suspected septic shock of unknown origin and TSS since the case met the criteria of TSS, although the patient did not have a history of tampon use. After the administration of 1,200 mg/day linezolid (LZD), 1,800 mg/day clindamycin (CLDM), 13.5 g/day piperacillin/tazobactam (PIPC/TAZ), and γ-globulin agents, her high fever, vital signs, and laboratory findings gradually improved. The clinical course during her first admission is shown in Fig. 1. The patient completely recovered and was discharged after three weeks of LZD administration. Because IFX was discontinued due to this episode, her psoriasis gradually deteriorated to a severe condition. The patient strongly desired to restart IFX treatment and was made aware of the risk of infectious diseases as a complication. IFX treatment once monthly with informed consent was restarted four months after the first episode and was administered three times, with an improvement of her psoriasis. One month after the last IFX dose, the patient again had severe diarrhea and a high fever, was admitted to the nearest general hospital, and recovered with treatment that was similar to the first episode. She had diarrhea, a high fever, and erythroderma indicative of shock five weeks after the second episode and was admitted to our hospital. Although no organisms were detected in the first and second episodes, S. agalactiae were detected in the blood, urine, and vaginal secretion cultures in the third episode. Drug sensitivity test results were the same for all samples, and all isolated strains were serotype type VI. During the third admission, empiric therapy with LZD, PIPC/TAZ, and CLDM were started and de-escalated to PIPC/TAZ and CLDM after detection of the causative bacteria. The clinical course including the psoriasis area severity index (8) of this case is summarized in Fig. 2; the severity of her psoriasis and menstruation cycles did not appear to be related to these infectious episodes. After the cessation of IFX-containing TNF-α inhibitor treatment, she has not developed either TSS or STSS for more than two years.

Figure 1.

Clinical course at the first admission. PIPC/TAZ: piperacillin/tazobactam, CLDM: clindamycin, LZD: linezolid, PCT: procalcitonin

Figure 2.

Clinical course of the present case. Small arrows indicate IFX administration; large arrows indicate toxic shock syndrome episodes. IFX: infliximab, STSS: streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, PASI: psoriasis area severity index, PCT: procalcitonin

Discussion

In the present case, we could detect GBS only in the third episode. However, we estimated that all episodes were caused by GBS, as they indicated similar clinical courses.

STSS due to S. agalactiae is rare infectious disease; a total of 40 GBS-STSS cases have been reported to date (9-22). Among these previous cases, 17 were men and 23 were women. Of 29 cases with available data, 22 (75.9%) were complicated with soft tissue infection, mostly necrotizing fasciitis. The mortality rates for these infections are high at 48.6% (18/37), which is much higher than that of TSS (23). The underlying disease and risk factors are summarized in Table. The most common underlying disease was diabetes mellitus (eight cases), followed by liver cirrhosis (seven cases); only three cases were healthy (one man and two women), but two cases reported using tampons. However, there have been no reported cases associated with the administration of TNF-α inhibitor therapy. S. agalactiae serotypes were available in 28 of 40 cases, serotype Ia, Ib, II, III, V, VI, and VII comprised 3, 10, 2, 4, 3, 5, and 1 case, respectively. Serotype Ib is the most commonly reported serotype. A United States survey of invasive GBS disease in nonpregnant adults reported the main serotypes to be V (29.2%) and Ia (24.3%), while VI was rare (0.1%) (4). In contrast, Lachenauer et al. reported that serotypes VI (24.7%) and VIII (35.6%) were predominant among GBS isolated from pregnant Japanese women (24). Thus, some region or racial differences might exist. In our case, GBS serotype VI was identified in the vaginal secretion, urine, and blood cultures in the third episode. The reason why we could not detect the causative bacteria in the first and second episodes might be that the vaginal and urine cultures were performed after the initiation of empiric antibiotics treatments. One possible reason for her onset is that GBS which colonized in the vagina caused sepsis through the urinary tract infection triggered by the TNF-α inhibitor, and finally resulted in STSS.

Table.

Underlying Diseases or Risk Factors of Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome Cases due to Streptococcus agalactiae.

| Underlying diseases (risk factor) | cases |

|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus | 8 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 7 |

| Healthy (tampon usage 2) | 3 |

| Splenectomy | 3 |

| Cancer | 2 |

| Cardiac disease | 2 |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 |

| Viral hepatitis type C | 1 |

| Behcet’s disease | 1 |

| Alcholic hapatopathy | 1 |

| Rheumatism | 1 |

| Renal disease | 1 |

| Dementia | 1 |

| Cholecystectomy | 1 |

| Sarcoidosis | 1 |

| Psoriasis with TNF-α inhibitor use (present case) | 1 |

| Unknown | 11 |

With respect to the relationship between psoriasis and TSS or STSS, Balci et al. reported higher S. aureus cultivation rates from skin lesions and higher superantigen production rates in patients with psoriasis compared with healthy controls (25). Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated significantly lower proliferation and secretion levels of cytokines IL-2 and IL-10 from regulatory T cells in response to streptococcal superantigen (Strep-A) in patients with psoriasis compared with healthy controls (26). These findings might be related to TSS or STSS development in patients with psoriasis, although there is no report regarding S. agalactiae superantigen and psoriasis. However, the present patient did not have any skin infection focus at the time of each onset.

The adverse events of TNF-α inhibitor therapy include serious infections. Sepsis cases were observed in 0.3-1% of cases (7,27,28). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are only 4 previous reports of TNF-α inhibitor-related STSS (29-32). All patients received etanercept in combination with prednisolone or methotrexate and developed necrotizing fasciitis with STSS due to S. pyogenes (29-32).

Although this is an extremely rare case of possible recurrent STSS due to S. agalactiae infection triggered by anti-TNF-α inhibitor therapy, this report is informative for dermatologists or infectious disease specialists. Clinicians should therefore avoid restarting biological agents in patients who have a history of TSS or STSS.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Todd J, Fishaut M, Kapral F, Welch T. Toxic-shock syndrome associated with phage-group-I staphylococci. Lancet 2: 1116-1118, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hajjeh RA, Reingold A, Weil A, Shutt K, Schuchat A, Perkins BA. Toxic shock syndrome in the United States: surveillance update, 1979-1996. Emerg Infect Dis 5: 807-810, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bohach GA, Fast DJ, Nelson RD, Schlievert PM. Staphylococcal and streptococcal pyrogenic toxins involved in toxic shock syndrome and related illnesses. Crit Rev Microbiol 17: 251-272, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Skoff TH, Farley MM, Petit S, et al. Increasing burden of invasive group B streptococcal disease in nonpregnant adults, 1990-2007. Clin Infect Dis 49: 85-92, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ekelund K, Skinhoj P, Madsen J, Konradsen HB. Invasive group A, B, C and G streptococcal infections in Denmark 1999-2002: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Clin Microbiol Infect 11: 569-576, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andrews MM, Parent EM, Barry M, Parsonnet J. Recurrent nonmenstrual toxic shock syndrome: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis 32: 1470-1479, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Favalli EG, Desiati F, Atzeni F, et al. Serious infections during anti-TNFα treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Autoimmun Rev 8: 266-273, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis: oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica 157: 238-244, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schlievert PM, Gocke JE, Deringer JR. Group B streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome: report of a case and purification of an associated pyrogenic toxin. Clin Infect Dis 17: 26-31, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas S, Cunha BA. Group B streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome with fulminant cellulitis. Heart Lung 25: 497-499, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gardam MA, Low DE, Saginur R, Miller MA. Group B streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in adults. Arch Intern Med 158: 1704-1708, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holmstrom B, Grimsley EW. Necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock-like syndrome caused by group B streptococcus. South Med J 93: 1096-1098, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tang WM, Ho PL, Yau WP, Wong JW, Yip DK. Report of 2 fatal cases of adult necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome caused by Streptococcus agalactiae. Clin Infect Dis 31: E15-E17, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsubara K, Mikamo H, Numa M, Yamamoto G, Kusano H, Takamine Y. Three fatal cases of invasive serotype VI group B streptococcal infection. J Infect 53: e139-e142, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang B, Ikebe T, Wada A, et al. Surveillance of group B streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in nonpregnant adults and characterization of the strains in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 59: 182-185, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reich HL, Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Group B streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome. Arch Dermatol 140: 163-166, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sims KD, Barton TD. Group B streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in an asplenic patient: case report and literature review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 25: 208-210, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Begley JS, Barnes RC. Group B streptococcus toxic shock-like syndrome in a healthy woman: a case report. J Reprod Med 52: 323-325, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sendi P, Johansson L, Dahesh S, et al. Bacterial phenotype variants in group B streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 15: 223-232, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chihara D, Sakamoto T, Murakami G, Takeoka T, Ohno T. An overwhelming post-splenectomy infection with toxic shock syndrome by group B Streptococcus. Rinsho Ketsueki (Jpn J Clin Hematol) 51: 253-257, 2010(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al Akhrass F, Abdallah L, Berger S, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae toxic shock-like syndrome: two case reports and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 92: 10-14, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikebe T, Chiba K, Shima T, et al. Evaluation of streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome caused by group B streptococcus in adults in Japan between 2009 and 2013. J Infect Chemother 21: 207-211, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Descloux E, Perpoint T, Ferry T, et al. One in five mortality in non-menstrual toxic shock syndrome versus no mortality in menstrual cases in a balanced French series of 55 cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27: 37-43, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lachenauer CS, Kasper DL, Shimada J, et al. Serotypes VI and VIII predominate among group B streptococci isolated from pregnant Japanese women. J Infect Dis 179: 1030-1033, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balci DD, Duran N, Ozer B, Gunesacar R, Onlen Y, Yenin JZ. High prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus cultivation and superantigen production in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol 19: 238-242, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang K, Li X, Yin G, Liu Y, Niu X, Hou R. Functional characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells differentiated in vitro from bone marrow-derived haematopoietic cells of psoriasis patients with a family history of the disorder. Br J Dermatol 158: 298-305, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 36: 898-906, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tobin AM, Kirby B. TNFα inhibitors in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. BioDrugs 19: 47-57, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uthman I, Husari A, Touma Z, Kanj SS. Fatal streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with etanercept. Rheumatology 44: 1200-1201, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of etanercept in children with polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48: 218-226, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Renaud C, Ovetchkine P, Bortolozzi P, Saint-Cyr C, Tapiero B. Fatal group A Streptococcus purpura fulminans in a child receiving TNF-α blocker. Eur J Pediatr 170: 657-660, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weinblatt ME, Abbott GF, Koreishi AF. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. N Engl J Med 360: 1770-1779, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]