Abstract

Cells of the vascular system release spherical vesicles, called microparticles, in the size range of 0.1–1 μm induced by a variety of stress factors resulting in variable concentrations between health and disease. Furthermore, microparticles have intercellular communication/signaling properties and interfere with inflammation and coagulation pathways. Today's most used analytical technology for microparticle characterization, flow cytometry, is lacking sensitivity and specificity, which might have led to the publication of contradicting results in the past.

We propose the use of nano-liquid chromatography two-stage mass spectrometry as a nonbiased tool for quantitative MP proteome analysis.

For this, we developed an improved microparticle isolation protocol and quantified the microparticle protein composition of twelve healthy volunteers with a label-free, data-dependent and independent proteomics approach on a quadrupole orbitrap instrument.

Using aliquots of 250 μl platelet-free plasma from one individual donor, we achieved excellent reproducibility with an interassay coefficient of variation of 2.7 ± 1.7% (mean ± 1 standard deviation) on individual peptide intensities across 27 acquisitions performed over a period of 3.5 months. We show that the microparticle proteome between twelve healthy volunteers were remarkably similar, and that it is clearly distinguishable from whole cell and platelet lysates. We propose the use of the proteome profile shown in this work as a quality criterion for microparticle purity in proteomics studies. Furthermore, one freeze thaw cycle damaged the microparticle integrity, articulated by a loss of cytoplasm proteins, encompassing a specific set of proteins involved in regulating dynamic structures of the cytoskeleton, and thrombin activation leading to MP clotting. On the other hand, plasma membrane protein composition was unaffected. Finally, we show that multiplexed data-independent acquisition can be used for relative quantification of target proteins using Skyline software. Mass spectrometry data are available via ProteomeXchange (identifier PXD003935) and panoramaweb.org (https://panoramaweb.org/labkey/N1OHMk.url).

All cell types are walled by a lipid bilayer held in place and penetrated by membrane associated and transmembrane proteins. Stimuli like injury, complement activation, apoptosis, shear stress and receptor-ligand interactions can induce the release of small spherical vesicles, which received a plethora of names in the past, but should be described as extracellular vesicles, a term covering all vesicle size ranges (1). Shed vesicles from the plasma membrane with diameters between 0.1 and 1.0 μm were called microparticles (MP)1. MP production starts with an increase in intracellular calcium, activation of calcium sensitive enzymes, cleavage of structural filaments, and formation of blebs on the surface of cells, which are finally shed off (2–4). MP are present in extracellular biological fluids and in plasma, where numbers were generally reported to increase under pathophysiological conditions (5–7). There is increasing evidence that MP are part of a sophisticated intercellular communication network and are involved in repair of damaged tissue (8, 9). Protein, lipid, and RNA composition is dependent on the stimuli and the cell type (8, 10, 11). Therefore, MP can be considered as a repository of physiological processes taking place in the vascular system, and are potentially useful biomarkers for the assessment of severity, treatment, and prognosis of vascular diseases. Clinical research on MP biomarkers has increased over the past years with flow cytometry (FCM) as the most used analytical method. Detection of MP with FCM relies on light scattering, which is dependent on refractive index, shape, and light absorption of vesicles (12). It had been shown with imaging techniques, like cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) and atomic force microscopy, that FCM detects only 0.1–2% of vesicles, because of the fact that the majority of vesicles are smaller than 300–500 nm in diameter (12–15). FCM relies furthermore on cell marker specific antibodies labeled with a fluorescent dye. MP are then detected by excitation of the dye and recording of the emission intensity. This limits the number of cell markers that can be tested per experiment because the excitation/emission wavelengths of two fluorescent dyes need to be sufficiently apart in order to avoid interferences.

Recognizing these limitations, a few groups, including us, have started to explore the use of proteomics technology in order to characterize circulating MP in plasma (5, 8, 16–19). Studies did not focus on, or had problems with, repeatability rendering statistical evidence testing a difficult task (5, 8, 18). There are three reasons for this: First, the MP proteome represents less than 0.01% of the plasma proteome, hence variation in high abundant plasma protein contaminations do variably suppress the detection of MP proteins (19). Second, there is no standardized MP isolation protocol, which could efficiently separate MP from soluble plasma proteins and lipoproteins (1). Third, there is no real consensus on pre-analytical measures for the treatment and storage of plasma samples. Most of former studies trying to establish best practice protocols were relying on FCM, often using Annexin-V as a marker for the enumeration of MP despite the fact that Annexin-V binds only to a subset of MP (12). Furthermore, there is no consistency in the literature of how samples were frozen and thawed, and how platelet-free plasma (PFP) was prepared before freezing (15).

In this study, we optimized the MP isolation procedure from PFP for label-free nano-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (nLC-MS/MS) based quantification of MP associated proteins. The excellent reproducibility of our procedure enabled studying the inter-individual protein variability between healthy donors and the effect of one freeze-thaw cycle of PFP on MP integrity. We show that MP protein compositions between healthy volunteers are remarkably stable, and that freezing/thawing causes damage to MP, potentially explaining some contradictory published results (1). The data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode used here is not considered a useful technology for diagnostic purposes, as data recording for each individual sample lasts several hours. Targeted protein quantification using parallelized selected reaction monitoring is a useful alternative, but only when protein biomarkers are well defined (20). However, MP shedding occurs on different cell types and in variable amounts depending on the environmental stimulus acting on the cells and the disease background. Therefore, each vascular disease might be characterized by its own set of biomarkers. This consideration renders the recently introduced data-independent acquisition (DIA) method an appealing alternative. DIA records an archive of fragment spectra (MS2), together with intact precursor peptide masses when full MS acquisitions (MS1) are intercalated, from essentially all detectable peptides with a single nLC-MS/MS run (21). This archive can then be interrogated in a targeted manner by using spectral libraries from formerly acquired fragment spectra together with exact mass and retention time information of the precursors. There are essentially two implementations of DIA methods on high-resolution mass spectrometers. One uses fixed precursor isolation windows across the entire nLC-MS/MS run, also known as SWATH MS (21), the other combines randomly assembled isolation windows of fixed size, called multiplexed MS/MS acquisition strategy (MSX) (22). The latter strategy has the potential advantage over the SWATH method that it can disrupt recurring suppression effects of highly over very low concentrated peptides in ionization and trapping, because of combining randomly different smaller m/z windows throughout the chromatographic separation of peptides. We have implemented a MSX3 method and compared the label-free, targeted protein quantification results using Skyline (23) with a top3 approach on DDA data (24) acquired on repeats of two different PFP volumes as input from 12 healthy donors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

All reagents were at least of analytical purity grade. Dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide (IAA), and LC-MS grade acetonitrile were from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland); urea, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and formic acid from Merck (Zug, Switzerland); TRIS and acetone from Sigma (Buchs, Switzerland); and sequencing-grade endoproteinase LysC and porcine trypsin from Promega (Dübendorf, Switzerland). Sudan Black was from Chroma, now available at Sigma.

PFP Preparation

Blood samples from 12 healthy volunteers (eight females, age 28–63, and four males, age 20–60) were collected by venipuncture into 10-ml Monovette® tubes supplemented with 1/10 volume of 0.106 m citric acid as anti-coagulant (Sarstedt, Sevelen, Switzerland) using a butterfly device 21-gauge needle by an experienced and qualified person. Volunteers were recruited within the laboratories of the Department of Clinical Research and gave their informed written consent in participating in this study, in-line with the rules of the institutional ethics requirements. Blood samples were centrifuged within 10 min after collection for 15 min at 1500 × g at room temperature (RT) without brake, and cell-free plasma was collected by aspiration 1 cm above the cell layer and collection in a 17-ml polypropylene tube (Huber and Co, Reinach, Switzerland), mixed and distributed into 2-ml polypropylene tubes (Sarstedt) followed by centrifugation for 2 min at 16,000 × g at RT. PFP from several tubes was carefully aspirated and transferred to a new tube, leaving 100 μl plasma behind, mixed and aliquots of 250 or 400 μl were frozen and stored at −80 °C. PFP samples were slowly thawed on ice water when used. An overview on the sets of PFP samples and the experimental design used in this study can be found in supplemental Fig. S1.

Isolation of MP

For the freezing study, MP of three PFP aliquots from the same donor were isolated immediately and frozen at −20 °C (referred to as “fresh”), three PFP aliquots each were frozen by snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen (“N2”), or in a −80 °C freezer, either by distributing tubes across a 81-holder cardboard freezer box (Sarstedt) as routinely done with plasma samples collected during clinical studies (“clinical”), or insulated by cotton within a box to slow the freezing process (“cot”), respectively.

When Sudan Black was used, 0.5 μl of a 0.2% (w/v) Sudan Black solution in DMSO was added to PFP. PFP was centrifuged at 16000 × g and RT for 20 min in case of 250 μl, or 40 min in case of 400 μl aliquots, respectively. The supernatant was carefully and quantitatively aspirated and pellets reconstituted in 250 μl PBS by vortexing for 10 s. MP were pelleted again by centrifugation at 16,000 × g and RT for 20 min, followed by two more washing steps. For protein separation on 10% SDS-PAGE, MP pellets were dissolved in 30 μl reducing gel electrophoresis sample buffer and heated for 5 min at 95 °C. For in-solution digestion, MP pellets were lysed in 10 μl urea buffer (8 m urea, 50 mm Tris/HCl pH 8.0) with agitation.

Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy (cryo-TEM)

MP were prepared as described above and the final MP pellet was re-suspended in 50 μl PBS. An aliquot of 4 μl was transferred to the carbon side of a holey carbon grid (Quantifoil) that was glow discharged previously. Excess fluid was blotted on the opposite side and the grids were plunge-frozen in liquid nitrogen cooled ethane. Imaging was carried out at −180 °C using a Gatan cryo-holder at 200 kV acceleration voltage on a FEI Tecnai F20 equipped with a Gatan energy filter and a 2048 × 2048 pixel CCD camera. All images were recorded using SerialEM (25) at magnifications ranging from 1850× (overviews) to 40,000×. Tilt series were recorded over a tilt range from −60° to 60° using a defocus range of 2–9 μm and 40–70 electrons per square angstrom. Tomograms were reconstructed using IMOD software (http://bio3d.colorado.edu/imod/) with cross correlation alignment and simultaneous iterative reconstruction technique (SIRT). Maps were recorded using SerialEM and the images were realigned using IMOD.

MP Protein Digestion and nLC-MS/MS

Proteins from dissolved MP were reduced and alkylated by addition of 1/10 of the MP suspension volume containing 0.1 m DTT in 100 mm Tris/HCl pH 8.0 for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by 1/10 volume of 0.5 m IAA in 100 mm Tris/HCl pH 8.0 for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Excess IAA was quenched by adding 4/10 volume of 0.1 m DTT solution. Then 3.5 μl digestion buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 2 mm CaCl2) and 1 μl LysC (0.1 μg/μl) were added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Samples were diluted with 79 μl digestion buffer and 1 μl trypsin (0.1 μg/μl) followed by incubation over night at ambient temperature. TFA (20%) was added to stop digestion to a final volume of 105 μl. Each sample was analyzed three times by data-dependent acquisition (DDA) by loading 5 μl on a Proxeon EASY-nLC1000 chromatograph connected to a QExactive orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Peptides were trapped on a Pepmap100 C18 Trap, 300 μm × 5 mm (Thermo Fisher), and separated by back flush onto the analytical column (C18 Aqua Magic, 3 μm, 100 Å, 75 μm × 150 mm) with a 90 min gradient from 5% to 40% solution B (95% ACN, 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. Full MS (resolution 70,000, automatic gain control target of 1e6, maximum injection time of 50 ms) and top10 MS2 scans (resolution 17,500, target of 1e5, 110 ms) were recorded alternatively in the range of 360 to 1400 m/z, with an inclusion window of 2 m/z, relative collision energy of 27, and dynamic exclusion for 20s. The data-independent acquisition (DIA) data was acquired with 1 full MS scan from 390 to 1010 m/z at resolution 35,000 and fill time of 55 ms, followed by 10 MS2 scans, isolating three randomly combined 10 m/z ion packages (MSX3) within the mass range from 400 to 1000 m/z, followed by another full MS scan. AGC for MS2 scans was set to 1e6, fill time to auto, and all other parameters were equal to the DDA mode.

Equal aliquots of PFP from 12 donors were pooled. MP were isolated from 400 μl pooled PFP and proteins separated on a 12% mini SDS-PAGE, which was cut into 12 bands. Each band was in-gel digested with trypsin and analyzed by DDA nLC-MS/MS as described above. The QExactive data were transformed to Mascot generic files with ProteomeDiscoverer v1.4 using the MS2 spectrum processor node applying de-isotoping and isotope intensity summing to the monoisotope with 20 mmu tolerance, as well as charge deconvolution.

DDA Data Interpretation

DDA data of all in-solution digested MP samples were processed with MaxQuant/Andromeda version 1.5.0.0 (MQ) searching against the forward and reversed SwissProt human protein database (Release 2013_09 and 2015_12) with the following parameters: Mass error tolerance for parent ions of 10 ppm and fragment ions of 20 ppm, trypsin cleavage mode (no P rule) with 2 missed cleavages, static carbamidomethylation on Cys, variable oxidation on Met and acetylation of protein N termini. For the samples of the 12 volunteers carbamoylation on Lys, and the freezer study samples phosphorylation on Ser, Thr, and Tyr were also included as optional modifications. Based on reversed database peptide spectrum matches a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) was set for acceptance of peptide spectrum matches (PSM), peptides, and proteins. The top3 peptide feature intensities of each protein group and LC-MS/MS run were summed to form the protein group “top3” intensity. Before data comparison, protein group intensities were median normalized within each experiment (supplemental Fig. S1).

Data from the in-gel digested MP pool was interpreted with MaxQuant (v1.5.0.0), EasyProt v2.3 build 747, and SearchGUI (v1.21.0)/PeptideShaker (v0.34.0) (27) using Amanda, X!Tandem, Myrimatch, and msgf+ as search engines, respectively, against the forward and reversed SwissProt human protein database, release 2013_09. Mass error tolerances for parent ions and fragment ions were set to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. Stringent trypsin cleavage was used with three allowed missed cleavages, and static carbamidomethylation on Cys, and variable oxidation of methionine as modifications. Peptide sequences accepted at a 1% PSM false discovery rate were exported from each search engine. Peptides confirmed by at least three search engines, or peptides with at least one other peptide with different sequence matching to the same protein, were accepted as true positives.

DIA MSX3 Data Interpretation

All MaxQuant peptide identifications at 1% FDR were used to build a spectrum library within Skyline (23). The protein intensities of 78 target proteins were extracted from the DIA MSX3 data using the three most intense peptides on MS1 and MS2 level. For MS2 intensities, at least five, and a maximum of 10 fragment ions were used depending on the peptide sequence. Correctness of extracted chromatographic peaks was evaluated by mProphet (1% FDR) followed by manual validation. We summed MS1 and MS2 intensities based on the following arguments: First, MS1 features were only accepted when corresponding MS2 features were present too (and vice versa). Second, MS1 intensities correlated very well with MS2 intensities with a median Spearman rank correlation coefficient of 0.913 (supplemental Table S1).

Data Evaluation and Statistical Analyses

Statistical testing between groups was done with Students t-tests and permutation-based FDR estimation to correct for multiple testing, between several groups with one-way ANOVA applying Tukey's honestly significant difference criterion to evaluate statistical significance (alpha = 0.01). Perseus (version 1.5.0.15) and Matlab (version R2010A) were used for statistical testing. Graphics were produced in Excel and R. Gene Ontology enrichment analyses were done with Cytoscape (version 3.0.2) and its BINGO plugin (version 2.44).

RESULTS

Reproducible MP Isolation

Washing MP only once with PBS resulted in MP massively contaminated by plasma proteins (supplemental Fig. S2A). Two or three additional washing steps removed plasma proteins, but it became possible to produce relatively pure MP preparations only by complete vacuum assisted liquid aspiration with a fine glass capillary (supplemental Fig. S2B). Unfortunately, yields of proteins differed between replicates, likely because of partial aspiration of invisible MP material. Staining the lipid fraction of MP with Sudan Black enabled the operator to aspirate quantitatively the supernatant liquid without touching the MP pellet. After some training, the operator could reproduce identical MP preparations even without the use of Sudan Black (see below).

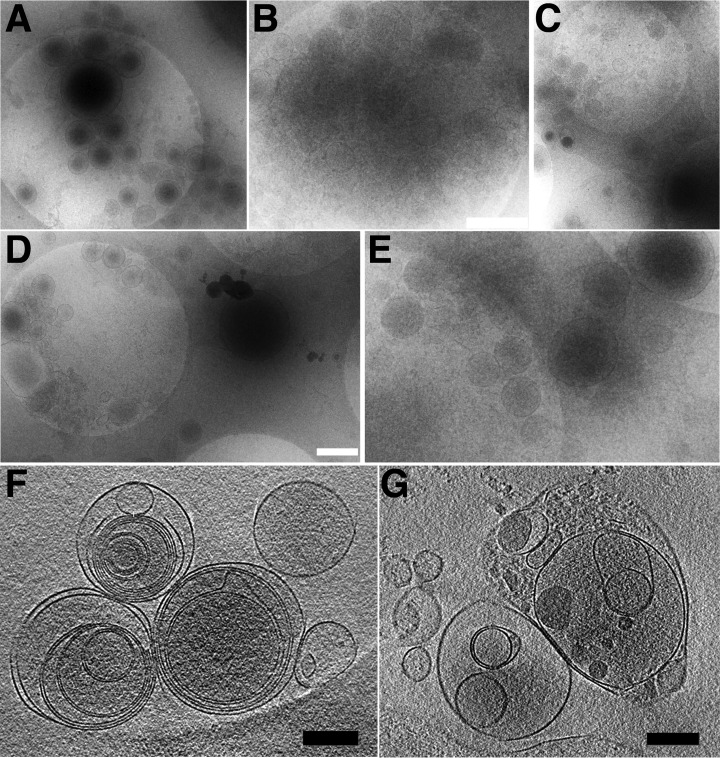

Confirmation of MP by cryo-TEM

Cryo-TEM was used to confirm the isolation of MP (Fig. 1). The isolated vesicles were generally 100 to 500 nm in diameter (Fig. 1A–1E), which is in the size range defined to represent circulating plasma MP. Therefore, we refrained from using the term extracellular vesicles as suggested by van der Pool and colleagues (1). We detected clumps of MP (Fig. 1B) and the tomographic representations in Fig. 1F and 1G, revealed that many of the vesicles contained smaller vesicular structures within the lumen, which might represent cellular organelles or remnants thereof, or could be an artifact of MP preparation. The shapes, sizes, and the vesicles-within-vesicle feature of MP corresponded well with the nanostructures reported recently by Issman and Yuana (15, 26), and confirmed successful isolation of MP from human plasma. We mathematically simulated the sedimentation behavior of MP and platelets (supplemental Fig. S3) and concluded that our applied centrifugation protocols removed larger vesicles (> 0.5 μm) and platelets during the preparation of PFP, and lost smaller extracellular vesicles (< 0.2 μm) during the washing of MP in PBS, corroborating the detected sizes.

Fig. 1.

Confirmation of MP by cryo-TEM. MP were isolated with three PBS washes without addition of SB and subjected to cryo-TEM. Panels A to E show five representative pictures at different magnification. Picture B depicts MP clumps. The white bars in B and D scale to 500 nm and the bright round shapes visible in each picture are holes in the carbon film with a diameter of 2 μm. Panels F and G show two slices through a volume of a tomographic composition from the same preparations showing multi-vesicular structures (F) and possibly encapsulated cellular organelles (G). The black bars scale to 200 μm.

Reproducible MP Isolation and Protein Digestion

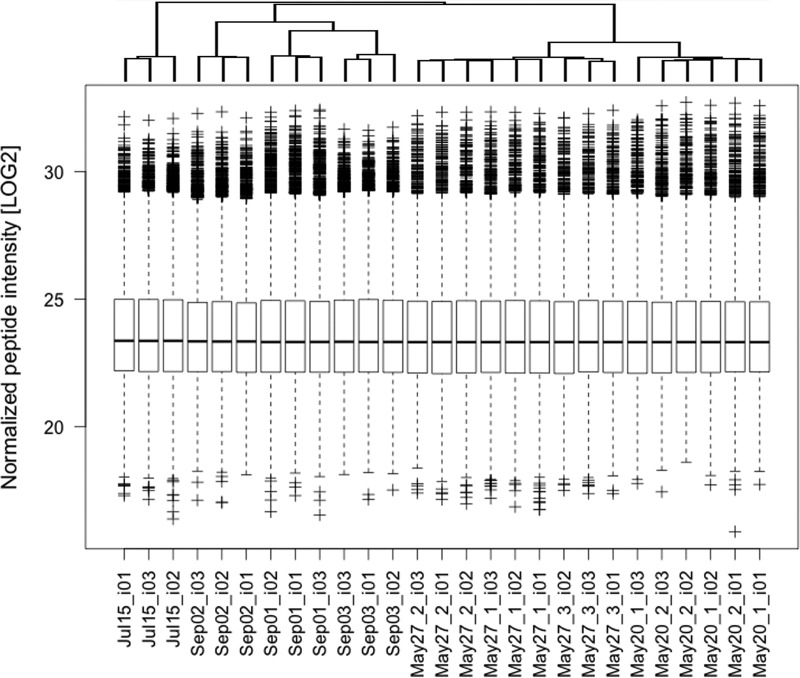

Cold acetone protein precipitation after reduction and alkylation enabled the use of Sudan Black for downstream nLC-MS/MS analysis, as Sudan Black was removed by acetone. However, the precipitation step caused irreproducible protein and peptide identifications between batches of MP preparations (results not shown). By omitting the protein precipitation step, we achieved reproducible peptide intensities from technical and biological replicates from the same donor prepared on the same day (intra-assay, Fig. 2, May 20 or May 27 runs) or on different days over a period of 3.5 months (interassay, Fig. 2 all runs). A total of 12,346 peptides were identified in at least two of the nine preparations (supplemental Table S2). The average coefficient of variation (CV) of peptide intensities between all 27 runs was 2.68 ± 1.67% (mean ± 1 S.D.). We observed nevertheless a clustering of samples (Fig. 2), which could be explained by the following facts: First, the May 20 and May 27 samples were analyzed with a 60-min ACN LC gradient, whereas the July and September samples were separated during 90-min. Second, the September samples were from a different blood draw than the July and May samples. There was also a day-to-day variability, most likely because of sample preparation issues. We concluded that the lipid-to-protein ratio in MP samples exceeds a critical value resulting in aberrant and nonquantitative protein precipitation with acetone. Despite the use of biological replicates and two different LC gradients, the resulting peptide intensities were very reproducible, which was corroborated by the excellent reproducibility of specific cell markers (supplemental Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Reproducibility in MP isolation and protein digestion. MP associated proteins were digested as described in the experimental procedures section and analyzed with a 60-min (May20 and May27 samples) or 90-min (July15 and Sep01 to Sep03 samples) ACN gradient, respectively. All the used 250 μl PFP aliquots were from the same donor, but prepared from two different blood samples being collected more than a year (May20, May27 and Jul15 samples) and 10 days (Sep01 to Sep03 samples) before use, respectively. The boxplots show the distributions of median normalized LOG2 peptide intensities as reported by MaxQuant software. The data is ordered according to hierarchical clustering (top). The first number after the date and an underscore relates to the sample number on the date of preparation. The _i0x (x = 1 to 3) relates to the LC-MS/MS run of this sample. None of the means were tested different from others (p = 0.05).

Label-free MP Proteome Quantification

We analyzed the MP proteomes of twelve healthy donors twice, using 250 μl and 400 μl PFP as input, and acquired data by DDA and DIA-MSX3, respectively. Proteins were quantified unsupervised from DDA data with MaxQuant and supervised for 78 target proteins with Skyline on the DIA-MSX3 data. We identified a total of 1436 proteins with all 24 samples, which represented 1330 nonredundant gene products (supplemental Table S3). Based on UniprotKB keywords, protein descriptions, and gene ontology terms, we classified these proteins as follows: 355 cell membrane or cell membrane associated, 766 cellular, 30 extracellular matrix (ECM), and 179 serum proteins. The last category was split into classes of proteins of the blood coagulation (20) and complement system (26), immunoglobulins (29), apolipoproteins (22) and others (82).

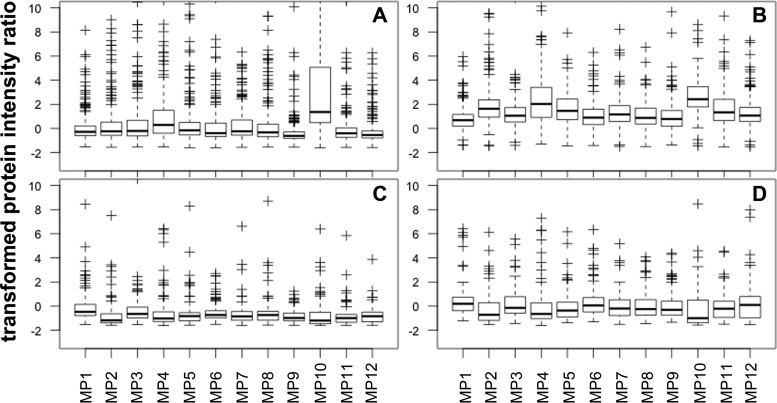

In order to assess the accuracy of the label-free protein quantification, we calculated the protein ratios between the 400 μl and 250 μl PFP samples for each of the twelve donors, and transformed the ratios to a theoretical median of zero by subtracting 1.6, the expected ratio. We plotted the ratios for cell membrane/cell membrane associated proteins and serum proteins separately, and compared the MaxQuant DDA derived top3 and LFQ ratios (Fig. 3). The LFQ ratios of serum proteins were centered on zero (the expected value), whereas the cell membrane protein ratios were shifted to higher values. In comparison, the top3 ratios of cell membrane proteins fulfilled the expectation of being centered on zero. The same applied for all other cell proteins (result not shown). The serum protein ratios were shifted to lower than expected values. The observation with the top3 data was confirmed by DIA-MSX3 data (not shown). We hypothesize that the relative contribution of truly MP associated proteins is increased relative to the soluble serum proteins in the 400 μl compared with the 250 μl PFP sample, because of the fact that the liquid supernatant was removed quantitatively from the MP pellets after each centrifugation/washing step. This sample workup procedure should result in a decreased relative contribution (mass spectrometry response) of serum proteins, consequently a decrease in the measured serum protein ratios between 400 μl and 250 μl PFP input. Under this consideration, the top3 intensity values appear to be better suited for relative protein quantification than the LFQ values, which is in agreement with observations by Ahrné and colleagues (24).

Fig. 3.

Quality check of label-free MP proteome quantification. Protein ratios were calculated between the 400 μl and 250 μl PFP input of 12 healthy donors (x axis) and transformed by subtraction of 1.6, the expected, theoretical ratio, in order to have a median ratio of zero (y axis). The upper panels A and B represent the ratios of cell membrane and cell membrane associated proteins, the lower panels C and D the ones of serum proteins. The panels on the left (A and C) show DDA MaxQuant top3 values, on the right (B and D) MaxQuant LFQ values, respectively. Only proteins identified in at least 12 out of 24 samples were considered for these figures.

With our hypothesis, it might be possible to distinguish true from false MP associated proteins. For instance, lipoproteins are considered to contaminate MP prepared by differential centrifugation because of similar densities (28), hence are not MP associated. Immunoglobulin chains and complement factors had been described to associate with MP (8, 18, 19). The median ratios of immunoglobulin chains and complement factors, like the ones of apolipoproteins, were smaller than zero, indicating no or only loose association of these proteins with MP (supplemental Fig. S5). However, only a quantitative enrichment assay for all these proteins could definitely distinguish true from false association with MP, a difficult task considering that MP protein mass represents less than 100 ppm of all plasma proteins ([19] and own data, not shown).

The reproducibility in DDA top3 cellular protein intensities across the twelve samples was good with CV's of 4.31 ± 2.44% and 3.67 ± 2.60% for the 250 μl and the 400 μl preparations, respectively. Median Spearman correlation coefficients of protein intensities between samples (PFP volume wise) and between different PFP volumes of identical samples were close to 0.9, with 78 and 86% of all proteins common to any pairwise comparison with the 250 μl and 400 μl preparations, respectively (supplemental Fig. S6). We concluded that it is possible to accurately quantify MP associated proteins using relatively small PFP volumes of 250 and 400 μl, and that the MP protein compositions of the twelve healthy volunteers used in this study were very similar.

Characterization of MP Composition

In order to gain a more in-depth view on the MP proteome and to build a comprehensive spectrum library for Skyline, we separated MP proteins from 400 μl of PFP pooled from the twelve donors into 12 SDS-PAGE fractions (supplemental Fig. S1). We identified 2120 proteins by combining the results of six different search engines applying stringent acceptance criteria (see experimental procedures, supplemental Fig. S7). This approach was warranted as MaxQuant/Andromeda picked up only 1431 proteins (67.5% of 2120 proteins) at a 1% FDR on the PSM level and requiring at least two unique peptides for a positive protein identification. The 2120 proteins were reduced to 2017 nonredundant gene products. The combination of this protein set with the one from in-solution digests described in this report resulted in 2357 nonredundant gene products of which 200 could be classified as serum proteins (supplemental Table S4). Other classes of note were 72 cell marker proteins of which 70 had a cluster of differentiation (CD) antigen annotation (supplemental Table S5), 644 proteins had a cell membrane localization with 419 having a transmembrane domain, 144 cell adhesion, 90 cell junction, 99 kinase, 239 cytoskeleton, and 120 GTP-binding proteins, and finally 659 proteins had an enzymatic activity covering all six enzyme classes (Table I, supplemental Table S4). We have plotted the summed protein intensities from the twelve 400 μl samples in order to get an impression about the relative abundance of these different protein classes in the MP proteome (supplemental Fig. S8). Mainly cell adhesion proteins with fewer cell junction proteins constituted the cell membrane proteome. The intracellular proteome was dominated by cytoskeleton followed by GTP-binding proteins. Apolipo- and complement pathway proteins dominated the contaminating serum proteome in intensity.

Table I. Classification of 2357 nonredundant MP associated gene products identified in this study. UniprotKB keywords, protein description, cellular component GO annotations, or cluster of differentiation categories (according to Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens (HLDA) Workshop) were used for classification.

| Class/Keyword (total) | Subclass | # of genes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell marker (total of 72) | T-cell | 41 |

| B-cell | 37 | |

| Dendritic cell | 18 | |

| NK cell | 31 | |

| Monocyte/Macrophage | 48 | |

| Granulocyte | 31 | |

| Platelet | 35 | |

| Erythrocyte | 17 | |

| Endothelial cell | 43 | |

| Stem or Progenitor cell | 34 | |

| Angiogenesis | 21 | |

| Transmembrane | 419 | |

| Cell membrane (different from Transmembrane) | 225 | |

| Cell adhesion | 144 | |

| Cell junction | 90 | |

| Cytoskeleton | 239 | |

| GTP-binding | 120 | |

| Kinases | 99 | |

| Chemotaxis | 16 | |

| Apoptosis | 80 | |

| Enzymes with a EC number (659) | 1. Oxidoreductases | 112 |

| 2. Transferases | 178 | |

| 3. Hydrolases | 258 | |

| 4. Lyases | 30 | |

| 5. Isomerases | 32 | |

| 6. Ligases | 49 | |

| ECM | 40 | |

| Innate immunity/Complement pathway | 56 | |

| Blood coagulation | 88 |

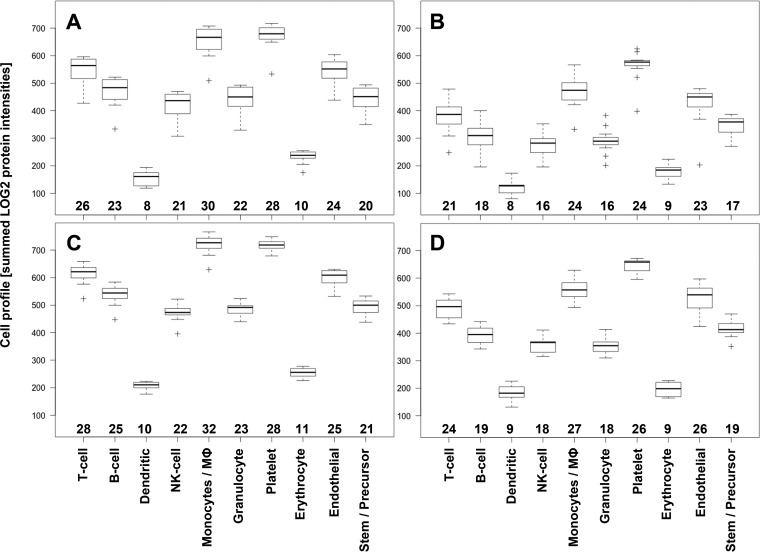

A major objective of MP research is the determination of the cellular origin of the vesicles. We used the quantitative data of 56 cell markers quantified in at least one of the 24 samples for this purpose (supplemental Fig. S9). We could quantify 45 of them by the DDA approach using 250 μl PFP and were able to improve the coverage to 48 markers when using 400 μl. The targeted extraction using Skyline revealed 40 and 44 proteins spanning three orders of intensity magnitudes (supplemental Fig. S9). Interestingly, it was possible to quantify CD34, an endothelial and precursor cell marker, in three samples (one in 250 μl and two in 400 μl) with the latter but not by the DDA approach. However, another progenitor cell marker, CD236, was quantified in seven 400 μl samples with DDA but not DIA-MSX3. The low rate of discovery for these markers points to a low concentration of precursor/stem cell derived MP in the plasma of healthy human.

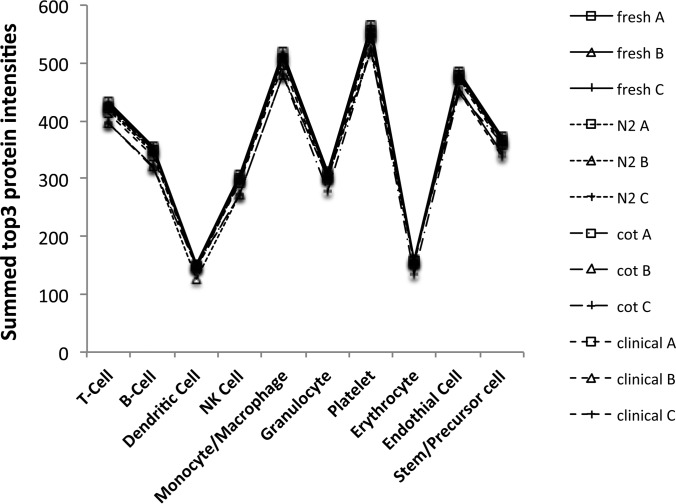

We summed the intensities of all cell markers representing a specific cell type according to listings in supplemental Table S5 to a surrogate for the concentration of cell-specific MP (Fig. 4). These cell profile patterns matched well between the DDA top3 derived and DIA-MSX3 Skyline extracted values with the exception of the two most abundant forms derived from platelet and monocyte/macrophage (MΦ). The profiles also revealed that MP derived from erythrocytes and dendritic cells were the least abundant, and stem/precursor cells ranked fifth, before B-cells, which appears to contradict the finding on the two individual markers CD34 and CD236. However, these cell profiles were a sum-up of intensities of all markers, many of which are known to be expressed on several cell types. The numbers of quantified cell type matching proteins are given at the bottom of each boxplot in Fig. 4 and illustrate that the numbers of matching proteins drive the apparent concentration. The protein intensities of 16 more specific cell markers were plotted individually in supplemental Fig. S10.

Fig. 4.

Cell Profiling of MP origin. The log2 transformed cell marker protein intensities were summed (y axis) to create cell profiles of MP origin for all twelve plasma samples analyzed. The twelve values are represented as boxplots for the 250 μl PFP (top row, panels A and B) and 400 μl PFP input (bottom row, panels C and D) using the DDA top3 values on the left (panels A and C) and DIA-MSX3 Skyline data on the right (panels B and D). The numbers of protein matching to a cell type are given above the x axis for each boxplot.

In addition, we also extracted in a targeted approach with Skyline the intensities of 34 proteins of different protein classes covering more than 3 orders of intensity magnitudes, and compared their distribution with DDA top3 intensities (supplemental Fig. S11). The variability of DIA-MSX3 derived intensities was generally bigger than from DDA top3 with mean CV's of 2.87 and 2.02 for DDA top3 250 μl and 400 μl PFP samples, and 3.29 and 3.04 for DIA-MSX3, respectively. The Spearman correlations of the median protein intensities from the 24 samples revealed good correlations (median coefficient of 0.92) between the DDA-top3 and DIA-Skyline values (supplemental Table S1).

In conclusion, our quantitative MP proteome analysis method is able to quantify circulating plasma MP associated proteins accurately, reveals details about their origin, and could be used to study possible mechanisms of MP formation and interaction with target cells by way of their composition (enzymes, receptors, cell adhesion molecules etc.). A multiplexed DIA approach, consuming only one third of the DDA acquisition time, is a valuable alternative to DDA, when protein intensities are extracted by a targeted approach, for instance by using Skyline.

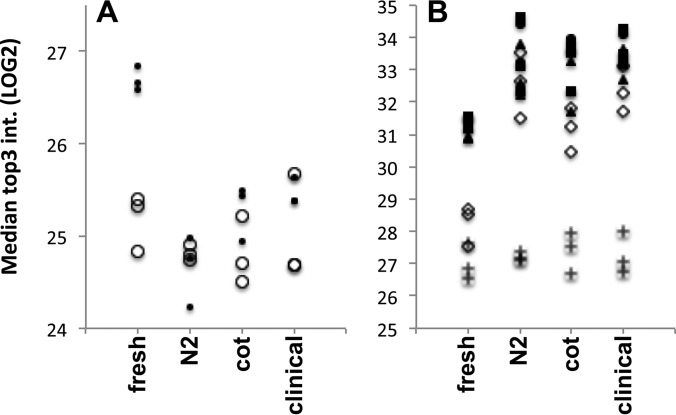

Impact of Freezing on MP Integrity

We prepared twelve 250 μl aliquots of fresh PFP from one of the twelve volunteers as outlined under Experimental Procedures. The MP isolates of fresh PFP were reconstituted in urea buffer and stored at −20 °C before digestion of proteins on the same days when MP were prepared from frozen PFP samples. Frozen PFP samples were used within 12 to 14 days after freezing. We identified a total of 769 nonredundant gene products, 756 when accepting only protein identifications present in at least two of three replicates of any condition (supplemental Table S6). MP of frozen PFP samples contained fewer proteins (600 ± 16 in N2, 667 ± 20 cot, and 688 ± 5 clinical preparation) than isolated from fresh PFP (730 ± 2). Classification of the identified proteins, revealed ∼108 proteins to be classical plasma proteins, including 11 different immunoglobulin chains, 24 complement factors, and 17 proteins associated with lipoprotein particles. The remaining 646 proteins were of cellular origin, including extracellular matrix. ANOVA testing of the median normalized top3 protein intensities revealed a set of 273 proteins that varied statistically significant with an FDR of 1% between the four PFP. Hierarchical clustering showed that variation was mostly because of lower intensities and complete losses of proteins in the frozen samples (supplemental Fig. S12). Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of the 273 varying proteins identified 221 proteins to have a cytoplasm annotation (corrected p = 6.0e-40). However, the 483 proteins without significant change also contained 298 cytoplasm proteins with significant enrichment (corrected p = 5.6e-12). Furthermore, the unchanged protein group was enriched with 154 plasma membrane proteins (corrected p = 6.6e-07), a class of proteins not enriched in the variable protein group. We identified 31 cell marker proteins, of which three (CD42d, CD45, HSPG2) had a significant change in abundance, albeit without any consequences on the twelve cell profiles (Fig. 5). These results indicated no loss of plasma membranes by freezing. There were 77 cytoskeleton proteins decreased after freezing (corrected p = 8.9e-24), whereas 88 cytoskeleton proteins remained unchanged (corrected p = 1.3e-12) (Fig. 6A). The latter cytoskeleton proteins belong to keratin filaments, myosin complexes and proteins of the erythrocyte cytoskeleton underlying the plasma membrane (spectrin, ankyrin etc.), whereas actin filaments and microtubules were affected by freezing. Interestingly, there were all three fibrin chains and fibronectin together with 8 other plasma proteins altered to higher concentrations by freezing (Fig. 6B). Fibrin chains are formed by proteolysis of fibrinogen by activated thrombin. We therefore measured thrombin activity in fresh and frozen PFP aliquots. Despite an apparent increase in thrombin activity after freezing, the difference was not significant (p = 0.14) and the measured thrombin activities were below the zero thrombin activity standard delivered with the assay (supplemental Fig. S13).

Fig. 5.

Cell marker profiles of the twelve samples from the freezing study. A total of 31 cell marker proteins, representing the origin of MP (supplemental Table S5), were identified in the 12 MP isolates produced from plasma aliquots, which were frozen in different ways or processed without freezing (see experimental procedures section). The top3 protein intensities, represented as LOG2 values (y-axes), of cell specific markers (x axis) were summed. The capital letters A, B, C after the sample names depict the three technical replicates analyzed for each condition.

Fig. 6.

Differential recovery of proteins dependent on plasma freezing condition. An ANOVA test revealed 273 proteins that were significantly changed in abundance between the four tested plasma storage conditions (p ≤ 0.01 at FDR = 1%), with cytoskeleton proteins representing a major group. The median top3 intensities of the three replicates from cytoskeleton proteins were plotted in panel A, with small dots (●) representing proteins changed significantly and open circles (○) without a change in abundance, respectively. Panel B, the median top3 intensities of classical serum proteins with increased abundance after freezing (APOA2, APOH, CO3, CO8G, F13A, HRG, IGHM, KV110) are depicted as crosses. The three fibrin chains, alpha (●), beta (▴), and gamma (■), and fibronectin (♢) are shown individually.

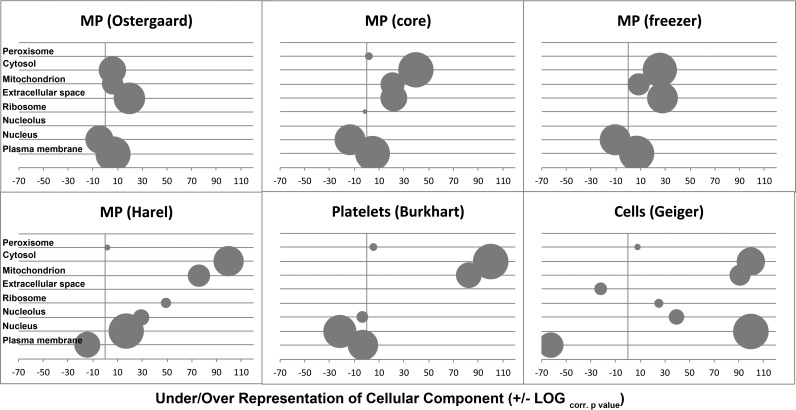

Discrimination of MP Proteome From Cellular Proteomes

We compared the proteomes of the twelve healthy volunteer MP preparations, referred to as MP core, and the freezer study with two published proteome studies on circulating MP (18, 29), and with a multicell proteome from eleven different cell lines (30), as well as one platelet proteome (31) by means of gene ontology (GO) cellular component terms (Fig. 7). Our proteomes and the one of Østergaard and colleagues (18) were very much alike, with plasma membrane proteins contributing a majority of proteins and being overrepresented, nucleus proteins clearly under-represented and ribosomal proteins present with only few members. This is in stark contrast with the MP proteome published by Harel et al. (29), where plasma membrane proteins were not the main class of proteins and being under-represented, whereas ribosome and nucleus proteins were over-represented and the latter formed the most populated class. This trait is seen in an amplified form in the whole cell proteomes of Geiger et al. (30). Proteins located in the mitochondrion were enriched in all proteomes, albeit moderately in the Østergaard et al. and our MP proteomes, but very strongly in the MP proteomes reported by Harel and colleagues (29), cell lines (30) as well as in platelets (31) (Fig. 7). The platelet proteome is further characterized by under-representation of nucleus (note: platelets are anucleate) and plasma membrane proteins, and without significant contribution of ribosomal proteins. We concluded that true MP proteomes, as represented by Østergaard and colleagues and our data sets, can clearly be discriminated from cellular and platelet proteomes by GO enrichment analysis, and that the MP proteome described by Harel and colleagues appears to be a hybrid between platelets and cells.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of MP proteome composition with cell proteomes. The over- or under-representation of GO slim cellular component terms (x axis) were plotted for the published proteomes of MP by Østergaard et al. (18) and Harel et al. (according to supplemental Table S2D) (29), 11 different cell lines analyzed by Geiger et al. (30), platelets by Burkhart et al. (31), and two proteome sets from this study using the core proteome identified from twelve healthy donors and from one single donor used for the freezer study, respectively. The data sets are marked in the header of each bubble plot. GO terms differentiating best MP from cell proteomes are given on the y axis. The bubble size represents the relative contribution of proteins in each set and the bubbles are placed horizontally according to the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate corrected p value in -LOG for over-representation and +LOG for under-representation.

DISCUSSION

The focus of this study was to establish a highly reproducible, label-free, and quantitative proteomics workflow for routine analysis of circulating plasma MP. We believe that such an approach is in high demand to further the understanding of MP function in vascular biology and to enable for specific and sensitive screening of MP in biomarker discovery and diagnostics. MP have mostly been studied by FCM in clinical studies, although FCM is a technology known to have shortcomings in the detection of MP (12–15). Nano-LC-MS/MS based proteomics is an unbiased and very sensitive analytical technology to establish an in-depth, quantitative protein parts list and to determine compositional changes, e.g. between health and disease. Despite this, only Østergaard and colleagues focused on the establishment of a reproducible workflow for quantitative proteome profiling of circulating plasma MP, achieving an intraday assay variability of less than 10% (18). We show here interassay variability of better than 3% over a period of more than 3 months by using two PFP samples prepared from different blood draws of the same individual. We believe that this improvement is because of near-complete aspiration of plasma and wash solution by vacuum pump assisted aspiration with a fine glass capillary. This allowed for fast and quantitative removal of all liquid and soluble plasma proteins. Therefore, the detection of low abundant MP associated membrane proteins in the presence of highly abundant plasma and cytoskeleton proteins could be improved substantially. However, we experienced occasionally losses of MP associated protein with some preparations, mostly when working with the smaller PFP input volume of 250 μl (for instance MP10, Fig. 3). These difficulties could be resolved by visualizing the tiny MP pellets with a dye, e.g. Sudan Black. Although not compatible with downstream reversed phase LC-MS analysis, the use of Sudan Black enabled to train the operator, in order to achieve quantitative accuracy to detect a relatively small difference of 1.6 by comparing MP preparations from 250 μl and 400 μl (Fig. 3).

A standard DDA-based acquisition method as used here would not be suitable as a diagnostic tool in clinical research, because of limited throughput. To alleviate this problem, DIA methods have recently gained a great deal of attraction. Here we report, that it is possible to extract quantitative data of similar quality and sensitivity with one LC-MS/MS run using a multiplexed DIA approach (DIA-MSX3) compared with three consecutive LC-MS/MS acquisitions with DDA (supplemental Figs. S9 to S11). The gain in speed by a factor of three compared with DDA, and the possibility to perform proteome discovery as well as targeted protein quantification at the same time, renders this approach very attractive.

We focused the performance comparison between the untargeted DDA and the targeted DIA-MSX3 approach on cell markers residing on the plasma membrane of vascular cells. Defining and quantifying the origin of MP in blood is key to characterize vascular diseases (5–7). FCM based profiling of MP origin is restricted to the use of one or two markers per cell type. Within the healthy population included in this study, we could identify a total of 70 markers with a cluster of differentiation annotation to which we added two proteins specifically expressed in endothelial cells (ESAM, HSPG2). Although this set of markers does not cover all commonly used with FCM (for instance CD62E, an endothelial cell specific marker, was missing), the generated cell profiles were in full agreement with vascular biology. For instance, dendritic cell derived MP were found to be the least abundant species followed by erythrocytes (Fig. 4). Dendritic cells reside mostly in tissue and the lymph system, hence are not exposed directly to the blood circulation. Erythrocytes do not have an active metabolism, therefore lack the energy consuming machinery to shed off MP. CD233, the erythrocyte specific band3 anion transporter, was amongst the most intense markers (supplemental Figs. S9 and S10), apparently contradicting the profile data. We argue that the band3 protein is very likely the most abundant plasma membrane protein of all vascular cells, hence not many erythrocyte-derived MP are necessary to increase CD233 concentration relative to other plasma membrane proteins. The low number of additional erythrocyte marker proteins corroborated the correctness of this assumption (Fig. 4). In fact, higher concentrations of erythrocyte-derived MP would probably indicate hemolysis of blood during the preanalytical preparation of PFP, or a disease like sickle cell disease (32). Platelet-derived MP are known to be the most abundant population (33, 34) and clearly confirmed by our profiling data (Fig. 4). Interestingly, with DDA data monocyte/macrophage (MΦ) derived MP overlapped in intensity with the ones from platelet, which was not the case with the DIA-MSX3 data. Many of the markers for monocytes/MΦ can also be expressed on other white blood cells (supplemental Table S5). We determined a (logical) correlation between protein numbers and apparent MP concentration (Fig. 4). This also explains the relatively high concentration of stem/precursor cell derived MP, as many of these markers are shared with differentiated cells (supplemental Table S5). Interrogating more specific markers, like CD34 and CD236, or the monocyte-specific CD14 (supplemental Fig. S10), relativizes the global profiles (Fig. 4). CD34 and CD236 were the least abundant ones, platelet markers the most abundant (as in the profiles), whereas monocyte/MΦ specific markers were on a similar intensity level like the ones from endothelial cells. One other observation from supplemental Fig. S10 was, that two endothelial cell and one monocyte/MΦ derived marker (CD71/HSPG2 and CD14) varied most in intensity of all markers between the twelve individuals. Factors inducing MP shedding from the vascular wall (endothelial cells) are increased shear stress, a product of blood pressure and heart rate, hypoxia, or inflammation. Monocytes/MΦ are key players in inflammatory processes during which they often interact with the vascular wall (35). Hence, it could be possible that endothelial cell and monocyte/MΦ MP shedding are orchestrated and a consequence of each person's lifestyle and environmental exposure. Intriguingly, we also observed big variability of angiogenesis and ECM proteins between the twelve healthy individuals (supplemental Fig. S8). These proteins play an important role in the hemostasis of the vascular wall, hence are likely expressed in endothelial cells and monocytes/MΦ. Taken together, the proteomics derived profiles of MP origin and the accurate, label-free protein quantification as presented here, enable vascular biology research with unprecedented possibilities. We exploited this possibility further to study the impact of freezing PFP on MP integrity.

The influence of the PFP freezing procedure on MP is controversially described in the literature. One recent report dealt with properties of extracellular vesicles from neutrophilic granulocytes (36). The authors concluded that vesicles should be used fresh in order to maintain their full biological activity, or can be stored at −80 °C to maintain their integrity, but snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen was destructive. Lacroix and colleagues studied pre-analytical parameters and impact of freezing on circulating plasma MP based on Annexin-V positive MP and coagulation propensity (37). Their results indicated that snap freezing of PFP didn't influence MP significantly compared with direct freezing at −80 °C. FCM was used to enumerate MP, which renders quantitative results ambiguous (1, 12–15). Very recently, Yuana and colleagues could not find any impact on extracellular vesicle number and size after a single freeze thaw cycle of PFP (38). Our proteomics approach was capable of quantifying hundreds instead of only few proteins by FCM; hence a more detailed and accurate view on MP protein composition and integrity was achieved. For instance, we detected in a former study equal levels of CD31 and CD41 positive MP by FCM, whereas the mass spectrometry response clearly indicated higher levels of CD41 (8). Here, we detected more than ten times higher concentrations of CD41 than CD31 (supplemental Table S3), corroborating this earlier finding.

We used older recommendations for PFP preparation, which were well established in our laboratory and partly supported by a recent study (38), using a high-speed second plasma centrifugation step to prepare PFP from cell-free plasma (39, 40). We thawed PFP slowly on water/ice, as recommended by Jy and colleagues (39), but later questioned by Trummer et al. (40), and very recently confirmed as nondestructive for erythrocyte, platelet and whole plasma derived extracellular vesicles (38). Our quantitative MP proteome assessment corroborated the finding of Lacroix et al. that any kind of freezing has an effect on MP integrity (37). However, our interpretations of the relative changes of MP protein quantity between fresh and frozen PFP samples contradict with some conclusions of Lacroix and colleagues, and confirm findings of Yuana et al. (38). Lacroix et al. advocated the use of a second low speed centrifugation of 2500 × g for 15 min in order to quantitatively remove any remnants of platelets from cell-free plasma, which they named “protocol A,” instead of a high speed centrifugation with 13,000 × g for 2 min, named “protocol B.” Their suggestion was based on the interpretation of higher FCM counts coming from platelet remnants detected as “platelet clumps” on cytospin filters after protocol B. We simulated mathematically the sedimentation behavior of MP and platelets using centrifugal speeds as defined in protocols A and B, and ours (16,000 × g for 2 min) (supplemental Fig. S3). All protocols cannot separate the largest MP (diameter 0.815–1 μm) from smallest platelets (1.50–1.84 μm) as they sediment always with the same speed. Furthermore, platelets and larger MP do sediment through a longer liquid column with protocol A than with protocol B, whereas our protocol achieves a performance in between the two Lacroix protocols (supplemental Fig. S3, panel B). In conclusion, protocol A removes more of the larger MP, or clumps of MP, which are better detected by FCM (15), than the other protocols. Therefore, less Annexin-V positive particles were counted with FCM by Lacroix et al. after use of protocol A (37). Importantly, platelet and vesicle sedimentation depends not only on centrifugal speed and centrifugation time but also on the length of the liquid column, i.e. vial dimensions, a parameter neglected in essentially all published studies.

Furthermore, the fact that Lacroix and colleagues detected increased thrombin generation and decreased coagulation time in PFP after freezing with protocol B, but not with protocol A, indicates an activation of coagulation by freezing extracellular vesicles containing PFP (37). It is known that thrombin is activated by freezing (41) and confirmed tentatively here (supplemental Fig. S13). With proteomics, we present strong evidence that increased fibrin and fibronectin association with MP occurred after freezing (Fig. 6B). Fibrinogen is cleaved by activated thrombin, forming fibrin filaments, which can associate with fibronectin and bind to MP membranes. This process is leading to MP aggregation as seen in Fig. 1B. Yuana and colleagues also confirmed clumping of platelet-derived vesicles (38). Lacroix and colleagues have likely misinterpreted such MP clumps as “platelet” clumps (37).

Here, we show that one freeze thaw cycle damaged vesicles most prominently when PFP was snap frozen. We observed partial losses of dynamic cytoskeletal structures such as actin filament associated and regulating elements, e.g. rho proteins (ARHGDIA, ARHGDIB, ARHGAP1, ARHGAP6, RHOA, DIAPH), and coronin (CORO1A), and microtubules with plus-end microtubule proteins (KIF2A, MAPRE1, PFP2R1A, DCTN2, ACTRIA), tethering actin filaments and microtubules to the plasma membrane. These proteins are involved in processes of endo- and exocytosis, form cell extensions (cilia, blebs, lamellipodia, or filopodia), and separate cell content during cell division or polarization. It appears therefore, that cytoskeleton structures tethered at single points to the plasma membrane are most vulnerable to MP rupture by freezing and were subsequently lost during the stringent washing procedure, whereas the constituents of the plasma membrane, i.e. cell markers, remained intact (Fig. 5).

There are many published proteome studies on extracellular vesicles, including MP and exsosomes from cancer cells, isolated blood cells, urine, ascites, and plasma (42). We are aware of only four studies on human circulating plasma MP (5, 8, 18, 29). We compared the proteome composition of our MP preparations with the ones from Østergaard et al. (18) and Harel et al. (29) together with one multi cell line proteome from Geiger et al. (30) and one platelet proteome set from Burkhart et al. (31) (Fig. 7). The protein patterns based on relative protein contributions to GO cellular components and their statistical enrichment within a proteome clearly revealed, that the MP proteome composition published by Harel et al. appears to be a composite of platelets and whole cells (Fig. 7). Harel and colleagues centrifuged blood at 4 °C (29). This causes cell death and platelet activation resulting in the formation of cell and platelet debris, which will be isolated together with MP by centrifugation. Therefore, we believe that the study of Harel and colleagues should not be considered as a MP biomarker discovery study. Furthermore, we propose, that the MP proteome signatures of Østergaard et al. (18) and our data sets, as presented in the top panels of Fig. 7, should be used as a quality criterion in future proteomics based MP studies. Last but not least, we believe that the protein set of 2357 nonredundant gene products described here (supplemental Table S4) is one of the most comprehensive and specific proteomes of circulating human plasma MP described so far in the literature.

In summary, we show that it is possible to isolate sufficient MP material for the relative, label-free quantification of around one thousand proteins with unprecedented reproducibility from only 250 μl human PFP. The corresponding protein profiles can be used as a quality control for MP preparations, to quantify cellular origin of MP, to discover structural changes on MP, and verify indirectly thrombin activation through freezing PFP, which was hardly possible with a commercially available thrombin activity measurement kit. Using targeted peptide feature extraction, it is possible to identify and quantify accurately the MP proteome from DIA-MSX3 data, which holds great promises for clinical studies on the involvement of MP in vascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Monika Stutz for her advice on pre-analytical procedures and Dr. Markus Müller for fruitful discussions. All the mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (43) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD003935. The DIA-MSX3 data analysis with Skyline is available on https://panoramaweb.org (direct link https://panoramaweb.org/labkey/N1OHMk.url).

Footnotes

Author contributions: S. B.-L. performed nLC-MS/MS and data interpretation; N. B. prepared MP samples; M.-I. I. performed cryo-TEM experiments and assembled tomographic pictures; B. Z. and C. J. helped with cryo-TEM experiments, interpretation of cryo-TEM pictures, and critical revision of manuscript; M. H. designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

* Electron microscopy images were acquired on a device supported by the Microscopy Imaging Center (MIC) of the University of Bern. The LC-MS/MS equipment was jointly sponsored by a Swiss National Science Foundation grant (R'Equip #316030-139231) and the University of Bern.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- MP

- microparticles

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- CV

- coefficient of variation

- DDA

- data-dependent acquisition

- DIA

- data-independent acquisition

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- FCM

- flow-cytometry

- IAA

- iodoacetamide

- MS1

- full mass window acquisition of intact peptide precursors

- MS2

- fragment spectrum acquisition

- MSX

- multiplexed data-independent fragment spectra acquisition strategy

- nLC-MS/MS

- nano-liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- PFP

- platelet-free plasma

- PSM

- peptide spectrum match

- RT

- room temperature

- S.D.

- standard deviation

- TEM

- transmission electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. van der Pol E., Böing A. N., Gool E. L., and Nieuwland R. (2016) Recent developments in the nomenclature, presence, isolation, detection and clinical impact of extracellular vesicles. J. Thromb. Haemost 14, 48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boulanger C. M., Amabile N., and Tedgui A. (2006) Circulating microparticles: a potential prognostic marker for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Hypertension 48, 180–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meziani F., Tesse A., and Andriantsitohaina R. (2008) Microparticles are vectors of paradoxical information in vascular cells including the endothelium: role in health and diseases. Pharmacol. Rep. 60, 75–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chironi G. N., Boulanger C. M., Simon A., George F. D., Freyssinet J. M., and Tegui A. (2009) Endothelial microperticles in diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 335, 143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Little K. M., Smalley M., Harthun N. L., and Ley K. (2010) The plasma microvesicle proteome. Semin. Thromb. Hemost 36, 845–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amabile N., Rautou P. E., Tedgui A., and Boulanger C. M. (2010) Microparticles: key protagonists in cardiovascular disorders. Semin. Thromb. Hemost 36, 907–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amabile N., Guignabert C., Montani D., Yeghiazarians Y., Boulanger C. M., and Humbert M. (2013) Cellular microparticles in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J 42, 272–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al Kaabi A., Traupe T., Stutz M., Buchs N., and Heller M. (2012) Cause or effect of arteriogenesis: compositional alterations of microparticles from CAD patients undergoing external counterpulsation therapy. PLoS ONE 7, e46822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sabin K., and Kikyo N. (2014) Microvesicles as mediators of tissue regeneration. Transl. Res. 163, 276–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peterson D. B., Sander T., Kaul S., Wakim B. T., Halligan B., Twigger S., Pritchard K. A. Jr, Oldham K. T., and Ou J. S. (2008) Comparative proteomic analysis of PAI-1 and TNF-alpha-derived endothelial microparticles. Proteomics 8, 2430–2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martinez M. C., and Andriantsitohaina R. (2011) Microparticles in angiogenesis: therapeutic potential. Circ. Res. 109, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arraud N., Linares R., Tan S., Gounou C., Pasquet J. M., Mornet S., and Brisson A. R. (2014) Extracellular vesicles from blood plasma: determination of their morphology, size, phenotype and concentration. J. Thromb. Haemost 12, 614–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Pol E., Hoekstra A. G., Sturk A., Otto C., van Leeuwen T. G., and Nieuwland R. (2010) Optical and nonoptical methods for detection and characterization of microparticles and exosomes. J. Thromb. Haemost 8, 2596–2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuana Y., Oosterkamp T. H., Bahatyrova S., Ashcroft B., Garcia Rodriguez P., Bertina R. M., and Osanto S. (2010) Atomic force microscopy: a novel approach to detect nanosized blood microparticles. J. Thromb. Haemost 8, 315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Issman L., Brenner B., Talmon Y., and Aharon A. (2013) Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy nanostructural study of shed microparticles. PLoS ONE 8, e83680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abdullah N. M., Kachman M., Walker A., Hawley A. E., Wrobleski S. K., Myers D. D., Strahler J. R., Andrews P. C., Michailidis G. C., Ramacciotti E., Henke P. K., and Wakefield T. W. (2009) Microparticle surface protein are associated with experimental venous thrombosis: a preliminary study. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost 15, 201–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bastos-Amador P., Royo F., Gonzalez E., Conde-Vancells J., Palomo-Diez L., Borras F. E., and Falcon-Perez J. M. (2012) Proteomic analysis of microvesicles from plasma of healthy donors reveals high individual variability. J. Proteomics 75, 3574–3584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Østergaard O., Nielsen C. T., Iversen L. V., Jacobsen Tanassi S., JT, and Heegaard N. H. (2012) Quantitative proteome profiling of normal human circulating microparticles. J. Proteome Res. 11, 2154–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smalley D. M., and Ley K. (2008) Plasma-derived microparticles for biomarker discovery. Clin. Lab. 54, 67–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gallien S., Duriez E., Crone C., Kellmann M., Moehring T., and Domon B. (2012) Targeted proteomic quantification on quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 1709–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gillet L. C., Navarro P., Tate S., Röst H., Selevsek N., Reiter L., Bonner R., and Aebersold R. (2012) Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: a new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, O111.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Egertson J. D., Kuehn A., Merrihew G. E., Bateman N. W., MacLean B. X., Ting Y. S., Canterbury J. D., Marsh D. M., Kellmann M., Zabrouskov V., Wu C. C., and MacCoss M. J. (2013) Multiplexed MS/MS for improved data-independent acquisition. Nat. Methods 10, 744–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MacLean B., Tomazela D. M., Shulman N., Chambers M., Finney G. L., Frewen B., Kern R., Tabb D. L., Liebler D. C., and MacCoss M. J. (2010) Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 26, 966–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahrné E., Molzahn L., Glatter T., and Schmidt A. (2013) Critical assessment of proteome-wide label-free absolute abundance estimation strategies. Proteomics 13, 2567–2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mastronarde D. N. (2005) Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol 152, 36–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yuana Y., Koning R. I., Kuil M. E., Rensen P. C., Koster A. J., Bertina R. M., and Osanto S. (2013) Cryo-electron microscopy of extracellular vesicles in fresh plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 31, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vaudel M., Burkhart J. M., Zahedi R. P., Oveland E., Berven F. S., Sickmann A., Martens L., and Barsnes H. (2015) PeptideShaker enables reanalysis of MS-derived proteomics data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 22–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuana Y., Levels J., Grootemaat A., Sturk A., and Nieuwland R. (2014) Co-isolation of extracellular vesicles and high-density lipoproteins using density gradient ultracentrifugation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 3, 23262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harel M., Oren-Giladi P., Kaidar-Person O., Shaked Y., and Geiger T. (2015) Proteomics of Microparticles with SILAC Quantification (PROMIS-Quan): A Novel Proteomic Method for Plasma Biomarker Quantification. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 1127–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Geiger T., Wehner A., Schaab C., Cox J., and Mann M. (2012) Comparative proteomic analysis of eleven common cell lines reveals ubiquitous but varying expression of most proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, M111.014050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burkhart J. M., Vaudel M., Gambaryan S., Radau S., Walter U., Martens L., Geiger J., Sickmann A., and Zahedi R. P. (2012) The first comprehensive and quantitative analysis of human platelet protein composition allows the comparative analysis of structural and functional pathways. Blood 120, e73–e82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Beers E. J., Schaap M. C. L., Berckmans R. J., Nieuwland R., Sturk A., van Doormaal F. F., Meijers J. C. M., and Biemond B. J. (2009) Circulating erythrocyte-derived microparticles are associated with coagulation activation in sickle cell disease. Haematologica 94, 1513–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berckmans R. J., Nieuwland R., Böing A. N., Romijn F. P., Hack C. E., and Sturk A. (2001) Cell-derived microparticles circulate in healthy humans and support low grade thrombin generation. Thromb. Haemost. 85, 639–646 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodríguez-Carrio J., Alperi-López M., López P., Alonso-Castro S., Carro-Esteban S. R., Ballina-García F. J., and Suárez A. (2015) Altered profile of circulating microparticles in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin. Sci. 128, 437–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jaipersad A. S., Lip G. Y., Silverman S., and Shantsila E. (2014) The role of monocytes in angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 63, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lőrincz Á.M, Timár C. I., Marosvári K. A., Veres D. S., Otrokocsi L., Kittel Á., and Ligeti E. (2014) Effect of storage on physical and functional properties of extracellular vesicles derived from neutrophilic granulocytes. J. Extracell. Vesicles 3, 25465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lacroix R., Judicone C., Poncelet P., Robert S., Arnaud L., Sampol J., and Dignat-George F. (2012) Impact of pre-analytical parameters on the measurement of circulating microparticles: towards standardization of protocol. J. Thromb. Haemost. 10, 437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yuana Y., Böing A. N., Grootemaat A. E., van der Pol E., Hau C. M., Cizmar P., Buhr E., Sturk A., and Nieuwland R. (2015) Handling and storage of human body fluids for analysis of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 29260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jy W., Horstman L. L., Jimenez J. J., Ahn Y. S., Biró E., Nieuwland R., Sturk A., Dignat-George F., Sabatier F., Camoin-Jau L., Sampol J., Hugel B., Zobairi F., Freyssinet J. M., Nomura S., Shet A. S., Key N. S., and Hebbel R. P. (2004) Measuring circulating cell-derived microparticles. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2, 1842–1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trummer A., De Rop C., Tiede A., Ganser A., and Eisert R. (2009) Recovery and composition of microparticles after snap-freezing depends on thawing temperature. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 20, 52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alesci S., Borggrefe M., and Dempfle C. E. (2009) Effect of freezing method and storage at −20 degrees C and −70 degrees C on prothrombin time, aPTT and plasma fibrinogen levels. Thromb. Res. 124, 121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Choi D.-S., Kim D.-K., Kim Y.-K., and Gho Y. S. (2013) Proteomics, transcriptomics and lipidomics of exosomes and ectosomes. Proteomics 13, 1554–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vizcaíno J. A., Csordas A., del-Toro N., Dianes J. A., Griss J., Lavidas I., Mayer G., Perez-Riverol Y., Reisinger F., Ternent T., Xu Q. W., Wang R., and Hermjakob H. (2016) 2016 update of the PRIDE database and related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D447–D456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.