Abstract

Aim

To investigate whether or not key populations affected by hepatitis B and hepatitis C are being tested sufficiently for these diseases throughout the European region.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for studies on HBV and HCV testing in the 53 Member States of the World Health Organization European Region following PRISMA criteria.

Results

136 English-language studies from 24 countries published between January 2007 and June 2013 were found. Most studies took place in 6 countries: France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. 37 studies (27%) addressed HBV, 46 (34%) HCV, and 53 (39%) both diseases. The largest categories of study populations were people who use drugs (18%) and health care patient populations (17%). Far fewer studies focused on migrants, prison inmates, or men who have sex with men.

Conclusions

The overall evidence base on HBV and HCV testing has considerable gaps in terms of the countries and populations represented and validity of testing uptake data. More research is needed throughout Europe to guide efforts to provide testing to certain key populations.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that globally 240 million people are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) (1), and 130 to 150 million with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) (2). According to Global Burden of Disease study findings, in 2010, hepatitis B caused almost 800 000 deaths and hepatitis C almost 500 000 deaths (3) – more than AIDS, tuberculosis, or malaria. Most of these deaths resulted from liver cirrhosis and liver cancer, both of which are common outcomes of long-term HBV and HCV infection.

Although the WHO European Region accounts for only a small proportion of the overall global burden of hepatitis B and C, both diseases are recognized as major public health threats within this region (4,5). A recent review estimated that 13.3 million adults in the WHO European Region are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a figure representing 1.8% of the adult population (6). It is estimated that adult hepatitis C RNA (HCV RNA) prevalence is 15.0 million, or 2.0% of the adult population.

The prevalence of HBV and HCV varies greatly across European countries, although gaps in the data and variations in study methodology hinder efforts to make reliable comparisons. HBsAg prevalence levels are reported to range from 0.1% (Ireland, the Netherlands) to 13.3% (Uzbekistan) (6). HCV RNA prevalence levels from 0.4% (Austria, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom) to 2.9% (Romania) have been noted (7). Within the European Union, countries in the south and east appear to have lower HBV and HCV prevalence overall than countries in the northwest (8).

Among the populations thought to be heavily affected by one or more forms of viral hepatitis in Europe, the World Health Organization identifies people who inject drugs (PWID) as “the key risk group for HCV infection in most European countries,” and also calls for attention to be given to men who have sex with men (MSM) engaging in high-risk behavior (9). Migrants are another population of concern in the region (6,10,11), as are prison inmates (12,13).

The field of viral hepatitis has seen important biomedical advances in recent years. The best antiviral drugs on the market can reduce severe consequences of chronic HBV infection (14) and can cure most cases of HCV (15). While the high cost of these drugs has raised concerns about their affordability, this is not the only obstacle to treating more people. The drugs are at risk of being greatly underutilized because most people who might benefit from them remain undiagnosed (16). An analysis of data from 7 European countries concluded that only 10 to 40% of people in those countries are aware of their HCV infection (17).

There are individual and public health benefits to learning one’s hepatitis B and C status. First, people who know they have one or both of these diseases can choose to make lifestyle changes to help protect the liver, such as no longer consuming alcohol (1). It is also crucial for more people with undiagnosed HBV and HCV to learn about their condition as a prerequisite to becoming candidates for treatment. Diagnosis of HBV and HCV has important prevention implications as well. Through prevention education, people infected with both diseases can learn how to take measures to avoid onward transmission. HCV-infected people who undergo treatment and achieve a cure are no longer at risk of spreading HCV to others.

Surveying the existing published knowledge on this topic to try to gain a better understanding of testing in Europe is an important preliminary step in strengthening the public health response to the challenges of reducing the number of undiagnosed infections and engaging more people in treatment. The aim of this scoping review is to investigate whether or not key populations affected by hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Europe are being tested sufficiently for these diseases throughout the region.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted on hepatitis B and C testing in the 53 Member States of the WHO European Region. The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched for articles and conference abstracts published between 1 January 2007 and 30 June 2013. There was no limit set for the year of data collection. Keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) for viral hepatitis B and C, testing and geographical scope were included in a broad search string (Supplementary material 1)(web extra material 1). The literature search was designed to identify English-language primary research articles and conference abstracts reporting on testing for hepatitis B or C in Europe. The protocol for this review was consistent with PRISMA criteria and was adapted from an earlier study that our group did on HCV among people who inject drugs (18,19).

Study selection

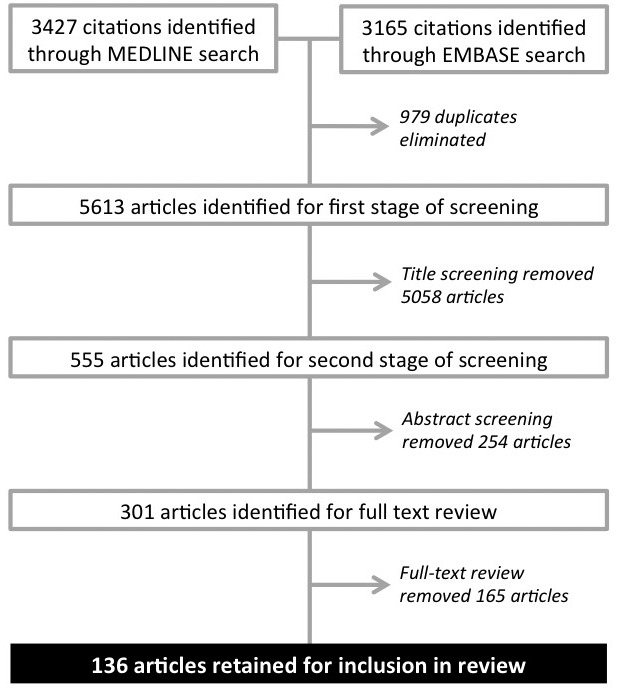

The screening process for study selection is shown in Figure 1. Following the MEDLINE and EMBASE searches, duplicate results were removed and the titles and abstracts of the remaining results were screened independently by two researchers (IS and JVL) to determine whether studies presented data on hepatitis testing in Europe. The same two researchers then reviewed the full text of the 301 articles identified through this process to determine which ones met the selection criteria. In order to be included, studies needed to report on the number and proportion of study participants tested for viral hepatitis. Studies were excluded if they focused on diagnostic aspects of viral hepatitis testing, if they reported data on pooled samples only, or if they involved the testing of deceased people, organ or tissue donors, or already-diagnosed individuals. Studies that utilized multiple contemporary samples from the same person also were excluded. If two or more studies reported on the same study population, then only the most recently published study was retained.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

Data extraction

Data were extracted and inserted into an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis using basic statistical methods. These data included study country; study design; study sample size; study setting; key characteristics of the study population; number and proportion of study participants tested for viral hepatitis; type of viral hepatitis that testing was intended to detect (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or both); viral hepatitis prevalence level or levels for those who were tested; and reported testing barriers. Decisions about which data to extract were guided by the criteria described in Box 1.

Box 1. Data extraction criteria.

• If a study reported pre- and post-intervention data, then only the pre-intervention (baseline) data were extracted.

• If a study reported on a longitudinal cohort with data available for multiple time points, then only the baseline data were extracted.

• If a study reported on multiple sequential cross-sectional study populations, then only data for the most recent study population were extracted.

Studies were sorted into separate categories on the basis of the type of study population. If a study met the criteria for being grouped with more than one type of population, it was placed in the category most closely associated with its primary focus. If a study cohort could be disaggregated into multiple population categories, then findings for the different populations were reported separately. Studies with study populations comprised of people living with HIV as well as studies pertaining to pregnancy and assisted reproductive technology were assessed separately from other patient studies because of the large numbers of studies in these subgroups of patients.

Results

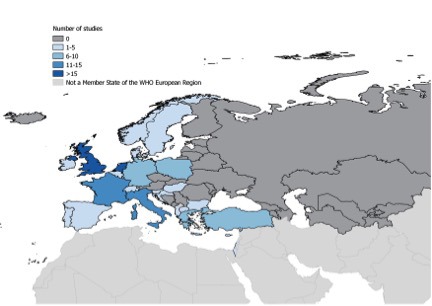

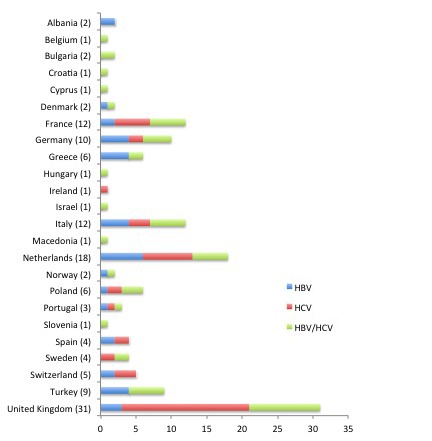

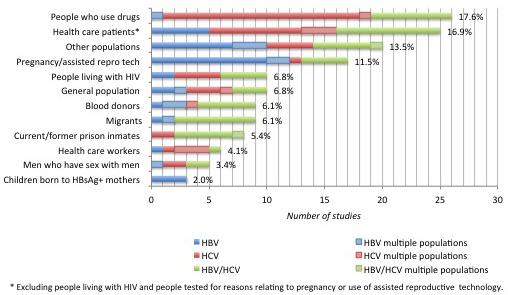

The review identified 136 studies from 24 of the WHO European Region’s 53 Member States (Figure 2, Figure 3). The countries with the largest numbers of studies were the United Kingdom (n=31), the Netherlands (n=18), France (n=12), Italy (n=12), and Germany (n=10). 37 (27.2%) studies addressed HBV, 46 (33.8%) addressed HCV, and 53 (39.0%) addressed both diseases. Studies were grouped into 12 study population categories (Figure 4). The populations most often studied were people who use drugs (17.6%), health care patient populations (16.9%), and people tested for reasons relating to pregnancy or use of assisted reproductive technology (11.5%). Although studies appeared in 78 different journals, 5 journals collectively accounted for one-quarter (27.2%) of studies: the Journal of Viral Hepatitis (n=15); Epidemiology and Infection (n=5); the Journal of Hepatology (n=6); the Journal of Medical Virology (n=5); and the European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (n=5). There was considerable variation in the number of studies published per year, with no obvious temporal trends.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of studies included in the review.

Figure 3.

Country settings for studies included in the review.

Figure 4.

Number of studies reporting on each disease and proportion of studies by population categories in the review.

136 studies were included in the analysis of studies grouped by study populations (20-156) (Supplementary material 2)(web extra material 2). Table 1 summarizes key findings for the 12 study populations.

Table 1.

Key findings for study populations

|

Study |

Number of studies |

Study sample size |

% tested |

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence |

Anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence |

|||||

|

population |

countries |

range |

median |

range |

median |

range (%) |

median (%) |

range (%) |

median (%) |

|

| Blood donors

(9 studies) |

Albania

Germany

Italy

Poland

Turkey |

Hepatitis B virus (HBV): 3

HCV: 1

HBV/

HCV: 5 |

801–148,320 |

30,716 |

100–100 |

100 |

0.1–9.1

(N = 8) |

1.1

(N = 8) |

0–0.5

(N = 6) |

0.2

(N = 6) |

| Health care workers

(6 studies) |

Germany

Greece

Netherlands

Poland |

HBV: 1

HCV: 4

HBV/HCV: 1 |

104–9029 |

572 |

100–100 |

100 |

0.5 (N = 1) |

0.5 (N = 1) |

1.4–1.7 (N = 4) |

1.4 (N = 4) |

| Health care patients

(25 studies) |

France

Germany

Greece

Italy

Macedonia

Netherlands

Poland

Spain

Sweden

Turkey

United Kingdom |

HBV: 5

HCV: 11

HBV/

HCV: 9 |

25–90,424* |

844* |

13.0–100† |

100† |

0.1–6.2 (N = 11) |

1.0 (N = 11) |

0–31.5 (N = 17) |

1.1 (N = 17) |

| People living with HIV

(10 studies) |

Bulgaria

France

Germany

Netherlands

Slovenia

Switzerland

United Kingdom |

HBV: 2

HCV: 4

HBV/

HCV: 4 |

48–31,765 |

770 |

60.8–100 |

100 |

2.1–6.5 (N = 5) |

3.9 (N = 5) |

4.4–43.8 (N = 7) |

10.7 (N = 7) |

| Migrants

(9 studies) |

Germany

Greece

Italy

Netherlands

United Kingdom |

HBV: 2

HCV: 0

HBV/

HCV: 7 |

250–5000‡ |

709‡ |

0–100§ |

99.3§ |

0.6–11.7 (N = 8)║ |

3.0 (N = 8)║ |

0.4–5.6 (N = 8)║ |

1.1 (N = 8)║ |

| Men who have sex with men

(5 studies) |

Belgium

Croatia

Italy

Netherlands

United Kingdom |

HBV: 1

HCV: 2

HBV/

HCV: 2 |

74–5230 |

387 |

68.6–100 |

100 |

0.8–12.0

(N = 2) |

6.4 (N = 2) |

0.7–1.2 (N = 2) |

1.0 (N = 2) |

| People who use drugs

(26 studies) |

Cyprus

Denmark

France

Israel

Italy

Netherlands

Sweden

Switzerland

United Kingdom |

HBV: 1

HCV: 18

HBV/

HCV: 7 |

40–97,250¶ |

661¶ |

0–100** |

100** |

0–52.3 (N = 4) |

4.8 (N = 4) |

6.3–86.5 (N = 21) |

50.0 (N = 21) |

| Current/former prison inmates

(8 studies) |

Bulgaria

France

Hungary

Italy

Portugal

United Kingdom |

HBV: 0

HCV: 2

HBV/

HCV: 6 |

151–318,550 |

550 |

2.6–100†† |

88.6†† |

0.7–6.7 (N = 4) |

1.4 (N = 4) |

4.8–77.4 (N = 7) |

28.6 (N = 7) |

| General population

(10 studies) |

France

Greece

Italy

Turkey

United Kingdom |

HBV: 3

HCV: 4

HBV/

HCV: 3 |

452–503,060 |

5057 |

100–100 |

100 |

0.5–2.5 (N = 4) |

1.5 (N = 4) |

1.0–5.5 (N = 4) |

2.6 (N = 4) |

| Children born to HBsAg-positive mothers

(3 studies) |

Italy

Netherlands |

HBV: 3

HCV: 0

HBV/

HCV: 0 |

100–2657 |

2280 |

75.4–100 |

79.8 |

0.6–0.7 (N = 2) |

0.7 (N = 2) |

- |

- |

| People tested for reasons relating to pregnancy or use of assisted reproductive technology

(17 studies) |

Albania

Denmark

Germany

Greece

Ireland

Netherlands

Norway

Portugal

Switzerland

Turkey

United Kingdom |

HBV: 12

HCV: 1

HBV/

HCV: 4 |

206–190,141‡‡ |

3932‡‡ |

16.5–100§§ |

100§§ |

0.1–7.3 (N = 11) |

0.7 (N = 11) |

0.2–0.9 (N = 4) |

0.4 (N = 4) |

| Other populations (20 studies) | Albania France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Netherlands Poland Spain Turkey United Kingdom | HBV: 10 HCV: 4 HBV/ HCV: 6 | 99–14,759║║ | 1000║║ | 3.7–100¶¶ | 100¶¶ | 0.1–11.9 (N = 9)*** | 2.1 (N = 9)*** | 0.1–64.3 (N = 9)*** | 2.8 (N = 9)*** |

*Based on 26 data points because one study reported separate study sample figures for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV).

†Based on 27 data points because two studies reported separate testing figures for HBV and HCV.

‡Based on 11 data points because one study reported separate study sample figures for multiple study arms.

§Based on 12 data points because (a) one study reported separate testing figures for HBV and HCV, and (b) one study reported separate testing figures for multiple study arms.

║Based on 9 data points because one study reported separate prevalence figures for multiple study arms.

¶Based on 27 data points because one study reported separate study sample figures for HBV and HCV.

**Based on 28 data points because (a) one study reported separate testing figures for HBV and HCV, and (b) one study reported separate testing figures for multiple study arms.

††Based on 9 data points because one study reported separate testing figures for HBV and HCV.

‡‡Based on 18 data points because one study reported separate study sample figures for HBV and HCV.

§§Based on 19 data points because two studies reported separate testing figures for HBV and HCV.

║║Based on 23 data points because two studies reported separate study sample figures for multiple study arms.

¶¶Based on 23 data points because two studies reported separate testing figures for multiple study arms.

***Based on 22 data points because one study reported separate prevalence figures for multiple study arms.

Discussion

Our review of hepatitis B and C testing research identified 136 studies from 24 of the 53 countries of the WHO European Region. The study populations most frequently studied were people who use drugs, health care patient populations, and people tested for reasons relating to pregnancy or use of assisted reproductive technology.

This review found a highly uneven distribution of HBV and HCV testing-related research outputs across the countries of the WHO European Region. 6 countries accounted for more than two-thirds of the studies included in the review, and the United Kingdom alone accounted for almost one-quarter of studies. Furthermore, there appears to be a concentration of research activity in the countries of the European Union/European Free Trade Association (EU/EFTA). The only countries outside of this area with studies included in the review were Albania (2 studies), Israel (2 studies), the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (2 studies), and Turkey (9 studies). For some countries with high estimated HBV or HCV prevalence, such as Romania, Ukraine, and the Russian Federation (6), we failed to identify any studies that met review inclusion criteria.

Also, much of the research about some key populations is reported by a relatively small number of countries. For example, the 26 studies reporting on HBV/HCV testing in people who use drugs are from 9 countries, and 12 are from 1 country (the United Kingdom). While the English-language restriction that our review employed may account for some of this imbalance, the review findings nonetheless raise the question of whether there might be knowledge gaps hampering an effective response to HBV and HCV in many European countries.

Although not the main objective of the study, we found median proportions of study participants tested for HBV or HCV to be 100% across most categories of study populations. At the same time, some categories in which the median proportion tested was 100% also included studies that reported relatively low levels of testing. For example, 33.6% of study participants in a study of people who use drugs were tested for HBV (39), and 13.0% of study participants in a study of asymptomatic patients in genitourinary medicine clinics were tested for HCV (59). However, we believe that our review findings around testing uptake are of limited value in assessing testing uptake levels in these populations because few studies had the specific purpose of examining HBV and HCV testing uptake. Most instead focused on measuring HBV and HCV prevalence. In many studies with 100% testing uptake, testing was actually a requirement for study enrolment.

This review identified only 9 studies reporting on HBV and HCV testing in migrant populations, which is a matter of concern since migration is an important factor in the European hepatitis B and C epidemics. All 9 studies were from countries with large migrant populations (Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) (157). The influx of migrants from countries with high HBV endemicity contributes considerably to the burden of chronic HBV in Europe, and chronic HBV levels of 3.7% to 6.9% have been found among migrants in 18 European countries (158). HBsAg prevalence in 8 migrant studies identified by our review ranged from 0.6% to 11.7%. Far less evidence is available regarding migration and HCV, but studies from France, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom suggest that migrant populations may account for a sizeable proportion of HCV cases (159). A 2013 Dutch study that estimated an 0.2% national HCV antibody prevalence level indicated that the largest number of cases was in migrants from HCV-endemic countries, with fewer cases among PWID and MSM (160).

Study populations as they occur in the real world are comprised of people who belong to multiple overlapping population groups. Information about different types of demographic and behavioral factors may be required to contextualize findings relating to some specific groups. For example, one of the “people living with HIV” studies in this review found a 43.8% anti-HCV prevalence level in 48 Bulgarian study participants. While it was a heterogeneous cohort, the authors noted that all of the study participants who tested positive for anti-HCV were young men with a history of both injecting drug use and imprisonment (108).

Similarly, prison populations and PWID populations may overlap considerably. Although imprisonment puts people at a high risk of HCV infection, this is through risky behaviors that take place before or during imprisonment such as injecting drug use. While injecting drug use is likely to be the most common HCV transmission pathway among prison inmates, it is not the only one (161). This complex situation may be difficult to tease apart with existing evidence. Although our review included 8 studies enrolling current and former prison inmates, and several of those studies report high levels of injecting drug use among study participants, only 1 provides disaggregated study results for inmates who are injecting drug users and those who are not (140).

Ultimately, more data will be needed to gain insight into large-scale patterns regarding who is being tested for HBV and HCV in European countries and why. The contribution of this scoping review is to reveal a lack of evidence in the published literature for three key populations in the European HBV and HCV epidemics: migrants, prison inmates, and men who have sex with men. Although a much larger number of studies focusing on people who inject drugs were identified, the concentration of this research in a small number of countries suggests the possibility of major country-level knowledge gaps in many countries.

Limitations

This review is subject to several limitations. Since it included only peer-reviewed studies and conference abstracts, publication bias may have significantly distorted the true picture regarding who is being tested for HBV and HCV, and in which settings. Reports from national agencies were not considered. These are likely to contribute substantially to the knowledge base regarding testing uptake. We recommend additional research to review reports from national agencies and other gray literature. Further, only articles published in English were included in this review, which may have biased our country distributions. Literature reviews of publications in other languages and of secondary literature that includes gray literature may help to provide a more complete picture. The diversity of study populations within population categories makes it challenging to interpret some of the review’s findings. Finally, there were major differences in sample sizes, which limits the comparability of findings within and across study populations.

Conclusions

This review identified a large number of studies on HBV and HCV testing in Europe, with a wide range of populations represented in those studies as well as a highly uneven geographical distribution of studies across the countries of the WHO European Region. The overall evidence base on HBV and HCV testing in the WHO European Region appears to have considerable gaps, particularly regarding the situation in non-EU/EFTA countries and among migrant populations, prison inmates and men who have sex with men. The evidence base might be expanded considerably if key stakeholders were to coordinate studies of HBV and HCV testing behavior with national public health agencies. Finally, the issues associated with obtaining valid testing uptake data from controlled study situations suggest a need for a different approach to measuring testing uptake. Data on self-reported testing history may provide important insights.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Erika F Duffell (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) and Lucas Wiessing (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) for their substantial input and for their reviews of earlier drafts of this article.

Funding This study was funded by the HIV in Europe Initiative. We thank the steering committee of said initiative for their review of the manuscript.

Ethical approval Not required.

Declaration of authorship JVL conceived the idea for the study and developed a protocol with support from JR, AS, and IS. The literature search was carried out by IS and JVL, who both also reviewed the articles, made decisions about which articles met inclusion criteria, and extracted the data. Data analysis and interpretation were carried out by all of the authors, and all likewise contributed to the article’s discussion and conclusions.

Competing interests All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional Material

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Prevention and control of viral hepatitis infection: Framework for global action. Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Fact sheet N. 164. Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatzakis A, Wait S, Bruix J, Buti M, Carballo M, Cavaleri M, et al. The state of hepatitis B and C in Europe: report from the hepatitis B and C summit conference. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirnschall G. WHO’s response to HIV/AIDS and viral hepatitis in the European region [speech]. Barcelona, Spain. HepHIV. 2014;2014:6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hope VD, Eramova I, Capurro D, Donoghoe MC. Prevalence and estimation of hepatitis B and C infections in the WHO European Region: a review of data focusing on the countries outside the European Union and the European Free Trade Association. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:270–86. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi-Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61:S45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahné SJ, Veldhuijzen IK, Wiessing L, Lim T-A, Salminen M, van de Laar M. Infection with hepatitis B and C virus in Europe: a systematic review of prevalence and cost-effectiveness of screening. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Action plan for the health sector response to viral hepatitis in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis B and C in the EU neighbourhood: prevalence, burden of disease and screening policies. Stockholm: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, Ndeffo-Mbah M, Galvani A, Kinner SA, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet. 2016;388:1089–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Prisons and health. Copenhagen: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liaw Y-F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and long-term outcome under treatment. Liver Int. 2009;29:100–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Jacobson IM. Antiviral therapy with nucleotide polymerase inhibitors for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61:S91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Improving the health of patients with viral hepatitis: Report by the Secretariat. Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merkinaite S, Lazarus JV, Gore C. Addressing HCV infection in Europe. reported, estimated and undiagnosed cases. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16:106–10. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gřtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiessing L, Ferri M, Grady B, Kantzanou M, Sperle I, Cullen KJ, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection epidemiology among people who inject drugs in Europe: a systematic review of data for scaling up treatment and prevention. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abou-Saleh M, Davis P, Rice P, Checinski K, Drummond C, Maxwell D, et al. The effectiveness of behavioural interventions in the primary prevention of hepatitis C amongst injecting drug users: a randomised controlled trial and lessons learned. Harm Reduct J. 2008;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson EM, Mandeville RP, Hutchinson SJ, Cameron SO, Mills PR, Fox R, et al. Evaluation of a general practice based hepatitis C virus screening intervention. Scott Med J. 2009;54:3–7. doi: 10.1258/rsmsmj.54.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blomé MA, Björkman P, Flamholc L, Jacobsson H, Molnegren V, Widell A. Minimal transmission of HIV despite persistently high transmission of hepatitis C virus in a Swedish needle exchange program: HCV in a needle exchange program. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:831–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brant LJ, Ramsay ME, Balogun MA, Boxall E, Hale A, Hurrelle M, et al. Diagnosis of acute hepatitis C virus infection and estimated incidence in low- and high-risk English populations: acute HCV diagnosis and incidence. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:871–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craine N, Parry J, O’Toole J, D’Arcy S, Lyons M. Improving blood-borne viral diagnosis: clinical audit of the uptake of dried blood spot testing offered by a substance misuse service. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:219–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craine N, Hickman M, Parry JV, Smith J, Walker AM, Russell D, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C in drug injectors: the role of homelessness, opiate substitution treatment, equipment sharing, and community size. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:1255. doi: 10.1017/S095026880900212X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curcio F, Villano G, Masucci S, Plenzik M, Veneruso C, De Rosa G. Epidemiological survey of hepatitis c virus infection in a cohort of patients from a ser. t in Naples, Italy. J Addict Med. 2011;5:43–9. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d131e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demetriou VL, van de Vijver DA, Hezka J, Kostrikis LG. Hepatitis C infection among intravenous drug users attending therapy programs in Cyprus. J Med Virol. 2010;82:263–70. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foucher J, Reiller B, Jullien V, Léal F, di Cesare ES, Merrouche W, et al. FibroScan used in street-based outreach for drug users is useful for hepatitis C virus screening and management: a prospective study. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:121–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hope V, Kimber J, Vickerman P, Hickman M, Ncube F. Frequency, factors and costs associated with injection site infections: findings from a national multi-site survey of injecting drug users in England. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hope V, Parry JV, Marongui A, Ncube F. Hepatitis C infection among recent initiates to injecting in England 2000-2008: Is a national hepatitis C action plan making a difference? J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hope VD, Hickman M, Ngui SL, Jones S, Telfer M, Bizzarri M, et al. Measuring the incidence, prevalence and genetic relatedness of hepatitis C infections among a community recruited sample of injecting drug users, using dried blood spots. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:262–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jauffret-Roustide M, Le Strat Y, Couturier E, Thierry D, Rondy M, Quaglia M, et al. A national cross-sectional study among drug-users in France: epidemiology of HCV and highlight on practical and statistical aspects of the design. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lidman C, Norden L, Kaberg M, Käll K, Franck J, Aleman S, et al. Hepatitis C infection among injection drug users in Stockholm Sweden: prevalence and gender. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:679–84. doi: 10.1080/00365540903062143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindenburg CEA, Lambers FAE, Urbanus AT, Schinkel J, Jansen PLM, Krol A, et al. Hepatitis C testing and treatment among active drug users in Amsterdam: results from the DUTCH-C project. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:23–31. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328340c451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loebstein R, Mahagna R, Maor Y, Kumik D, Elbaz E, Halkin H, et al. Hepatitis C, B, and human immunodeficiency virus infections in illicit drug users in Israel: prevalence and risk factors. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonald SA, Hutchinson SJ, Cameron SO, Innes HA, McLeod A, Goldberg DJ. Examination of the risk of reinfection with hepatitis C among injecting drug users who have been tested in Glasgow. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mössner BK, Skamling M, Jørgensen TR, Georgsen J, Pedersen C, Christensen PB. Decline in hepatitis B infection observed after 11 years of regional vaccination among Danish drug users. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1635–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Leary MC, Hutchinson SJ, Allen E, Palmateer N, Cameron S, Taylor A, et al. The association between alcohol use and hepatitis C status among injecting drug users in Glasgow. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreuder I, van der Sande MA, de Wit M, Bongaerts M, Boucher CA, Croes EA, et al. Seroprevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among opioid drug users on methadone treatment in the Netherlands. Harm Reduct J. 2010;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senn O, Seidenberg A, Rosemann T. Determinants of successful chronic hepatitis C case finding among patients receiving opioid maintenance treatment in a primary care setting. Addiction. 2009;104:2033–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stephens B. Is it worth testing unstable drug users for hepatitis C? London: British Association for the Study of the Liver Annual Meeting 7-9 September 2011:Poster P68. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tait J, Stephens B, McIntyre P, Evans M, Dillon J. Dry blood spot testing for hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: reaching the populations other tests cannot reach. Amsterdam; 48th Annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 24 April 2013 - 28 April 2013:Poster 498. [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Berg CHSB, van de Laar TJW, Kok A, Zuure FR, Coutinho RA, Prins M. Never injected, but hepatitis C virus-infected: a study among self-declared never-injecting drug users from the Amsterdam Cohort Studies. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:568–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Houdt R, Bruisten SM, Speksnijder AG, Prins M. Unexpectedly high proportion of drug users and men having sex with men who develop chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:529–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witteck A, Schmid P, Hensel-Koch K, Thurnheer M, Bruggmann P, Vernazza P. Management of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in drug substitution programs. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13193. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ansemant T, Ornetti P, Garrot J-F, Pascaud F, Tavernier C, Maillefert J-F. Usefulness of routine hepatitis C and hepatitis B serology in the diagnosis of recent-onset arthritis: systematic prospective screening in all patients seen by the rheumatologists of a defined area - Brief report. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:268–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnold DT, Bentham LM, Jacob RP, Lilford RJ, Girling AJ. Should patients with abnormal liver function tests in primary care be tested for chronic viral hepatitis: cost minimisation analysis based on a comprehensively tested cohort. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barril G, Castillo I, Arenas MD, Espinosa M, Garcia-Valdecasas J, Garcia-Fernandez N, et al. Occult hepatitis C virus infection among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2288–92. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bosevska G, Kuzmanovska G, Sikole A, Dzekova-Vidimilski P, Polenakovic M. Screening for hepatitis B, C and HIV infection among patients on haemodialysis (cross sectional analysis among patients from two dialysis units in the period January to July 2005). Prilozi. 2009;30:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cano J, Cervera R, Berciano M, Villa J, Garcia P, Espinosa J. Screening for hepatitis B virus in a Department of Clinical Oncology in Spain. Stockholm: European Cancer Congress, 23-27 Sept 2011:Poster 3415. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chevaux J-B, Nani A, Oussalah A, Venard V, Bensenane M, Belle A, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C and risk factors for nonvaccination in inflammatory bowel disease patients in Northeast France. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:916–24. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flisiak R, Halota W, Horban A, Juszczyk J, Pawlowska M, Simon K. Prevalence and risk factors of HCV infection in Poland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:1213–7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834d173c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gańczak M, Szych Z. Infections with HBV, HCV and HIV in patients admitted to the neurosurgical department of a teaching hospital. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2008;42:231–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gańczak M, Korzeń M, Szych Z. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among surgical nurses, their patients and blood donation candidates in Poland. J Hosp Infect. 2012;82:266–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guennoc X, Narbonne V, Jousse-Joulin S, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Dougados M, Daurčs JP, et al. Is screening for hepatitis B and hepatitis C useful in patients with recent-onset polyarthritis? The ESPOIR cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1407–13. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ippolito AM, Niro GA, Fontana R, Lotti G, Gioffreda D, Valvano MR, et al. Unawareness of HBV infection among inpatients in a Southern Italian hospital: unawareness of HBV infection. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kakisi OK, Grammatikos AA, Karageorgopoulos DE, Athanasoulia AP, Papadopoulou AV, Falagas ME. Prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV infections among patients in a psychiatric hospital in Greece. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1269–72. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marcos M, Alvarez F, Brito-Zerón P, Bove A, Perez-De-Lis M, Diaz-Lagares C, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Sjögren’s syndrome. Prevalence and clinical significance in 603 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:616–20. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McClean H, Carne CA, Sullivan AK, Menon-Johansson A, Gokhale R, Sethi G, et al. National audit of asymptomatic screening in UK genitourinary medicine clinics: case-notes audit. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:506–11. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.009572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muche M, Darstein F, Stein A, Hofmann J, Pfaffenbach S, Somasundaram R. Prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B and C among patients attending a German emergency department: is a risk assessment questionnaire a useful pre-screening tool? Amsterdam; 48th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 24 April 2013 - 28 April 2013:Poster 981. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okan V, Yilmaz M, Bayram A, Kis C, Cifci S, Buyukhatipoglu H, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Int J Hematol. 2008;88:403–8. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Özaslan E, Demirezer A, Yavuz B. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in Turkish healthy individuals. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1436–7. doi: 10.1097/10.1097/MEG.0b013e328321b124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palazzi C, D’Amico E, D’Angelo S, Nucera A, Petricca A, Olivieri I. Hepatitis C virus infection in Italian patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:101–3. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ross RS, Viazov S, Khudyakov YE, Xia GL, Lin Y, Holzmann H, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus in an orthopedic hospital ward. J Med Virol. 2009;81:249–57. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sjöberg K, Widell A, Verbaan H. Prevalence of hepatitis C in Swedish diabetics is low and comparable to that in health care workers. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:135–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f476f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slavenburg S, Verduyn-Lunel FM, Hermsen JT, Melchers WJG, te Morsche RHM, Drenth JP. Prevalence of hepatitis C in the general population in the Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2008;66:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spenatto N, Boulinguez S, Mularczyk M, Molinier L, Bureau C, Saune K, et al. Hepatitis B screening: who to target? A French sexually transmitted infection clinic experience. J Hepatol. 2013;58:690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tweed E, Brant L, Hurrelle M, Klapper P, Ramsay M, Hepatitis Sentinel Surveillance Study Group Hepatitis C testing in sexual health services in England, 2002-7: results from sentinel surveillance. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:126–30. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vermehren J, Schlosser B, Domke D, Elanjimattom S, Müller C, Hintereder G, et al. High prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in two metropolitan emergency departments in Germany: a prospective screening analysis of 28,809 patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ydreborg M, Söderström A, Hĺkanson A, Alsiö Ĺ, Arnholm B, Malmström P, et al. Look-back screening for the identification of transfusion-induced hepatitis C virus infection in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43:522–7. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.562526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Balogun MA, Parry JV, Mutton K, Okolo C, Benons L, Baxendale H, et al. Hepatitis B virus transmission in pre-adolescent schoolchildren in four multi-ethnic areas of England. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:916–25. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown AE, Ross DA, Simpson AJH, Erskine RS, Murphy G, Parry JV, et al. Prevalence of markers for HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection in UK military recruits. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:1166–71. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810002712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cai W, Poethko-Müller C, Hamouda O, Radun D. Hepatitis B virus infections among children and adolescents in Germany: migration background as a risk factor in a low seroprevalence population. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:19–24. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ef22d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Castillo I, Bartolomé J, Quiroga JA, Barril G, Carreńo V. Hepatitis C virus infection in the family setting of patients with occult hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1198–203. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coyne KM, Banks A, Heggie C, Scott CJ, Grover D, Evans C, et al. Sexual health of adults working in pornographic films. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:508–9. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cuypers WJ, Niekamp AM, Keesmekers R, Spauwen L, Hollman D, Telg D, et al. High prevalence of HIV, other sexually transmitted infections and risk profile in male commercial sex workers who have sex with men in the Netherlands. Québec City, Canada; 19th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research, July 10-13 2011:Poster P1-S2.11. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hickman M, McDonald T, Judd A, Nichols T, Hope V, Skidmore S, et al. Increasing the uptake of hepatitis C virus testing among injecting drug users in specialist drug treatment and prison settings by using dried blood spots for diagnostic testing: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:250–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Karaosmanoglu HK, Aydin OA, Sandikci S, Yamanlar ER, Nazlican O. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B: do blood donors represent the general population? J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:181–3. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, Zervou E, Babameto A, Craja B, Hyphantis H, et al. Hepatitis B remains a major health priority in Western Balkans: results of a 4-year prospective Greek-Albanian collaborative study. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meffre C, Le Strat Y, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Dubois F, Antona D, Lemasson J-M, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in France in 2004: social factors are important predictors after adjusting for known risk factors. J Med Virol. 2010;82:546–55. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pazdiora P, Böhmová Z, Kubátová A, Menclová I, Morávková I, Prŭchová J, et al. Screening family and sexual contacts of HBsAg+ persons in the Pilsen region. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2012;61:51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Resuli B. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Albania. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:849. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sahajian F, Bailly F, Vanhems P, Fantino B, Vannier-Nitenberg C, Fabry J, et al. A randomized trial of viral hepatitis prevention among underprivileged people in the Lyon area of France. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:182–92. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stamouli M, Velonakis E, Panagiotou I, Totos G. Prevalence of hepatitis B among Greek naval recruits. Berne, Switzerland. Swiss Medlab. 2012;12-14:C03. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Taylor A, Hutchinson SJ, Gilchrist G, Cameron S, Carr S, Goldberg DJ. Prevalence and determinants of hepatitis C virus infection among female drug injecting sex workers in Glasgow. Harm Reduct J. 2008;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tresó B, Barcsay E, Tarján A, Horváth G, Dencs Á, Hettmann A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HCV, HVB, and HIV infection among prison inmates and staff, Hungary. J Urban Health. 2012;89:108–16. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9626-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Trevisan A, Bruno A, Mongillo M, Morandin M, Pantaleoni A, Borella-Venturini M, et al. Prevalence of markers for hepatitis B Virus and Vaccination Compliance Among Medical School Students in Italy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:1189–91. doi: 10.1086/592414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Urbanus AT, van den Hoek A, Boonstra A, van Houdt R, de Bruijn LJ, Heijman T, et al. People with multiple tattoos and/or piercings are not at increased risk for HBV or HCV in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walz A, Wirth S, Hucke J, Gerner P. Vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) from mothers negative for HBV surface antigen and positive for antibody to HBV core antigen. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1227–31. doi: 10.1086/605698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zuure FR, Davidovich U, Coutinho RA, Kok G, Hoebe CJPA, van den Hoek A, et al. Using mass media and the internet as tools to diagnose hepatitis C infections in the general population. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bissinger A, Enders G, Schalasta G, Vergopoulos A, Enders M. Frequency of hepatitis B antigen positive pregnant women with high viral loads detected during routine antenatal care in Germany. Amsterdam; 48th Annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 24 April 2013 - 28 April 2013:Poster 967. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bjerke SEY, Vangen S, Holter E, Stray-Pedersen B. Infectious immune status in an obstetric population of Pakistani immigrants in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:464–70. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frischknecht F, Brühwiler H, Sell W, Trummer I. Serological testing for infectious diseases in pregnant women: are the guidelines followed? Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;140:w13138. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gun I, Ertugrul S, Kaya N, Akpak YK. Seroprevalence among Turkish pregnant women. Health Med. 2012;6:2471. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harder KM, Cowan S, Eriksen MB, Krarup HB, Christensen PB. Universal screening for hepatitis B among pregnant women led to 96% vaccination coverage among newborns of HBsAg positive mothers in Denmark. Vaccine. 2011;29:9303–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heininger U, Vaudaux B, Nidecker M, Pfister RE, Posfay-Barbe KM, Bachofner M, et al. Evaluation of the compliance with recommended procedures in newborns exposed to HBsAG-positive mothers: a multicenter collaborative study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:248–50. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181bd7f89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hughes C, Grundy K, Emerson G, Mocanu E. Viral screening at the time of each donation in ART patients: is it justified? Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3169–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karatapanis S, Skorda L, Marinopoulos S, Papastergiou V, Drogosi M, Lisgos P, et al. Higher rates of chronic hepatitis B infection and low vaccination-induced protection rates among parturients escaping HBsAg prenatal testing in Greece: a 2-year prospective study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:878–83. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328354834f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knorr B, Maul H, Schnitzler P. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among women at reproductive age at a German university hospital. J Clin Virol. 2008;42:422–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Koruk I, Koruk S, Copur AÇ, Simsek Z. An intervention study to improve HBsAg testing and preventive practices for hepatitis B in an obstetrics hospital. TAF Prev Med Bull. 2011;10:287–92. doi: 10.5455/pmb.20101215040249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kristiansen MG, Eriksen BO, Maltau JM, Holdo B, Gutteberg TJ, Mortensen L, et al. Prevalences of viremic hepatitis C and viremic hepatitis B in pregnant women in Northern Norway. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1141–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lambert J, Jackson V, Coulter-Smith S, Brennan M, Geary M, Kelleher TB, et al. Universal antenatal screening for Hepatitis C. Ir Med J. 2013;106:136–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Op de Coul EL, Hahné S, van Weert YW, Oomen P, Smit C, van der Ploeg K, et al. Antenatal screening for HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis in the Netherlands is effective. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pepas L, MacMahon E, el Toukhy T, Khalaf Y, Braude P. Viral screening before each cycle of assisted conception treatment is expensive and unnecessary: a survey of results from a UK inner city clinic. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2011;14:224–9. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2011.627624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pereira A, Fernandes A, Pinheiro L. Pre-conception and prenatal care in Braga Region. Tallinn, Estonia: 20th European Workshop on Neonatology, 27th - 30th June, 2012: Abstract 26. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Heiligenberg M, van der Loeff M, de Vries H, Geerlings S, Prins M, Prins J. Low prevalence of asymptomatic STI in HIV-infected heterosexual males and females, visiting an HIV outpatient clinic in the Netherlands. Québec City, Canada; 19th Biennial Conference Of The International Society For Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research, July 10-13 2011: Poster P1-S5.27. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Matser A, Geskus R, Heijman T, Urbanus A, Prins J, de Vries H, et al. Lifestyle as marker of Hepatitis C infection in HIV infected MSM in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Québec City, Canada; 19th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research, July 10-13 2011:Oral 10-04. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Popivanova N, Boykinova O, Baltadzhiev I, Stoilova Y, Novakor S, Dineva A, et al. Human hepatitis viruses B and C among HIV-infected patients - clinical and epidemiological features. Probl Infect Parasit Dis. 2009;37:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Reuter S, Oette M, Wilhelm FC, Beggel B, Kaiser R, Balduin M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of hepatitis B and C virus infections in treatment-naïve HIV-infected patients. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 2011;200:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s00430-010-0172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Seme K, Lunar MM, Tomazic J, Vidmar L, Karner P, Maticic M, et al. Low prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections among HIV-infected individuals in Slovenia: a nation-wide study, 1986-2008. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Steedman NM, McMillan A. Hepatitis B testing and vaccination in patients recently diagnosed with HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:83–4. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Turner J, Bansi L, Gilson R, Gazzard B, Walsh J, Pillay D, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in HIV-positive individuals in the UK - trends in HCV testing and the impact of HCV on HIV treatment outcomes. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:569–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Urbanus AT, van de Laar TJ, Stolte IG, Schinkel J, Heijman T, Coutinho RA, et al. Hepatitis C virus infections among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: an expanding epidemic. AIDS. 2009;23:F1–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wandeler G, Gsponer T, Bregenzer A, Gunthard HF, Clerc O, Calmy A, et al. Hepatitis C virus infections in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: a rapidly evolving epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1408–16. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Winnock M, Bani-Sadr F, Pambrun E, Loko M-A, Lascoux-Combe C, Garipuy D, et al. Prevalence of immunity to hepatitis viruses A and B in a large cohort of HIV/HCV-coinfected patients, and factors associated with HAV and HBV vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29:8656–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Akcam FZ, Uskun E, Avsar K, Songur Y. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus seroprevalence in rural areas of the southwestern region of Turkey. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:274–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Brant LJ, Hurrelle M, Balogun MA, Klapper P, Ahmad F, Boxall E, et al. Sentinel laboratory surveillance of hepatitis C antibody testing in England: understanding the epidemiology of HCV infection. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:417. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brant LJ, Hurrelle M, Collins S, Klapper PE, Ramsay ME. Using automated extraction of hepatitis B tests for surveillance: evidence of decreasing incidence of acute hepatitis B in England. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:1075–86. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brant LJ, Hurrelle M, Balogun MA, Klapper P, Ramsay ME. the Hepatitis Sentinel Surveillance Study Group. Where are people being tested for anti-HCV in England? Results from sentinel laboratory surveillance. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:729–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cozzolongo R, Osella AR, Elba S, Petruzzi J, Buongiorno G, Giannuzzi V, et al. Epidemiology of HCV infection in the general population: a survey in a southern Italian town. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2740–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Defossez G, Verneau A, Ingrand I, Silvain C, Ingrand P, Beauchant M, et al. Evaluation of the French national plan to promote screening and early management of viral hepatitis C, between 1997 and 2003: a comparative cross-sectional study in Poitou-Charentes region. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:367–72. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f479ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Delarocque-Astagneau E, Meffre C, Dubois F, Pioche C, Le Strat Y, Roudot-Thoraval F, et al. The impact of the prevention programme of hepatitis C over more than a decade: the French experience. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:435–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fabris P, Baldo V, Baldovin T, Bellotto E, Rassu M, Trivello R, et al. Changing epidemiology of HCV and HBV infections in Northern Italy: a survey in the general population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:527–32. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318030e3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ozkan S, Atak A, Bozdayi G, Turkcuoglu S, Maral I. Community-based research: cost of the tests used for anti-HBc total seropositivity only and hepatitis B screening. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:782–6. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zacharakis G, Kotsiou S, Papoutselis M, Vafiadis N, Tzara F, Pouliou E, et al. Changes in the epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection following the implementation of immunisation programmes in northeastern Greece. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:pii: 19297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Acar A, Kemahli S, Altunay H, Kosan E, Oncul O, Gorenek L, et al. The significance of repeat testing in Turkish blood donors screened with HBV, HCV and HIV immunoassays and the importance of S/CO ratios in the interpretation of HCV/HIV screening test results and as a determinant for further confirmatory testing. Transfus Med. 2010;20:152–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dettori S, Candido A, Kondili LA, Chionne P, Taffon S, Genovese D, et al. Identification of low HBV-DNA levels by nucleic acid amplification test (NAT) in blood donors. J Infect. 2009;59:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kaźmierczak M, Ciebiada M, Pękala-Wojciechowska A, Pawlowski M, Pietras T, Antczak A. Prevalence of viruses HBV, HCV and HIV in blood donors at the Regional Centre of Blood Donation and Blood Treatment in Poznan in the years 2008-2010. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:290–7. doi: 10.20452/pamw.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Öner S, Yapici G, Şaşmaz CT, Kurt AÖ, Buğdayci R. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and VDRL seroprevalence of blood donors in Mersin, Turkey. Turk J Med Sci. 2011;41:335–41. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Romanň L, Velati C, Cambič G, Fomiatti L, Galli C, Zanetti AR, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection among first-time blood donors in Italy: prevalence and correlates between serological patterns and occult infection. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:281. doi: 10.2450/2012.0160-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wiegand J, Luz B, Mengelkamp A-K, Moog R, Koscielny J, Halm-Heinrich I, et al. Autologous blood donor screening indicated a lower prevalence of viral hepatitis in East vs West Germany: epidemiological benefit from established health resources. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:743–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Heidrich B, Cetindere A, Beyaz M, Basaran M, Braynis B, Raupach R, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis marker in immigrant populations: a prospective multicenter screening approach in a real world setting. Barcelona, Spain; 47th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver: Poster 987. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jafferbhoy H, Miller MH, McIntyre P, Dillon JF. The effectiveness of outreach testing for hepatitis C in an immigrant Pakistani population. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:1048–53. doi: 10.1017/S095026881100152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lewis H, Burke K, Begum S, Ushiro-Limb I, Foster G. P56 What is the best method of case finding for chronic viral hepatitis in migrant communities? Gut. 2011;60(Suppl 2):A26–26. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300857a.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Milionis C. Serological markers of hepatitis B and C among juvenile immigrants from Albania settled in Greece. Eur J Gen Pract. 2010;16:236–40. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2010.525631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Richter C, Beest GT, Sancak I, Aydinly R, Bulbul K, Laetemia-Tomata F, et al. Hepatitis B prevalence in the Turkish population of Arnhem: implications for national screening policy? Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:724–30. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tramuto F, Mazzucco W, Maida CM, Affronti A, Affronti M, Montalto G, et al. Serological pattern of Hepatitis B, C, and HIV infections among immigrants in Sicily: epidemiological aspects and implication on public health. J Community Health. 2012;37:547–53. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Veldhuijzen IK, Wolter R, Rijckborst V, Mostert M, Voeten HA, Cheung Y, et al. Identification and treatment of chronic hepatitis B in Chinese migrants: Results of a project offering on-site testing in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Veldhuijzen IK, van Driel HF, Vos D, de Zwart O, van Doornum GJJ, de Man RA, et al. Viral hepatitis in a multi-ethnic neighborhood in the Netherlands: results of a community-based study in a low prevalence country. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.05.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Barros H, Ramos E, Lucas R. A survey of HIV and HCV among female prison inmates in Portugal. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16:116. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kirwan P, Evans B, Sentinel Surveillance of Hepatitis Testing Study Group. Brant L. Hepatitis C and B testing in English prisons is low but increasing. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33:197–204. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Marques NM, Margalho R, Melo MJ, da Cunha JGS, Meliço-Silvestre AA. Seroepidemiological survey of transmissible infectious diseases in a Portuguese prison establishment. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:272–5. doi: 10.1016/S1413-8670(11)70188-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Murray E, Jones D. Audit into blood-borne virus services in Her Majesty’s Prison Service. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:347–8. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pontali E, Ferrari F. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and/or hepatitis C virus co-infections in prisoners infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Int J Prison Health. 2008;4:77–82. doi: 10.1080/17449200802038207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Popov G, Plochev K, Pekova L, Pishmisheva M, Popov T, Tchervenyakova T. Prevalence of viral hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis among inmates of Bulgarian prisons. Amsterdam; 48th Annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 24 April 2013 - 28 April 2013:Poster 986. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Verneuil L, Vidal J-S, Ze Bekolo R, Vabret A, Petitjean J, Leclercq R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of the whole spectrum of sexually transmitted diseases in male incoming prisoners in France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:409–13. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0642-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Slusarczyk J, Malkowski P, Bobilewicz D, Juszczyk G. Cross-sectional, anonymous screening for asymptomatic HCV infection, immunity to HBV, and occult HBV infection among health care workers in Warsaw, Poland. Przegl Epidemiol. 2012;66:445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Topka D, Theodosopoulos L, Elefsiniotis I, Saroglou G, Brokalaki H. Prevalence of hepatitis B in haemodialysis nursing staff in Athens. J Ren Care. 2012;38:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zaaijer HL, Appelman P, Frijstein G. Hepatitis C virus infection among transmission-prone medical personnel. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1473–7. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1466-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bozicevic I, Lepej SZ, Rode OD, Grgic I, Jankovic P, Dominkovic Z, et al. Prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections and patterns of recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Zagreb, Croatia. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:539–44. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Di Benedetto MA, Di Piazza F, Amodio E, Taormina S, Romano N, Firenze A. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and enteric protozoa among homosexual men in western Sicily (south Italy). J Prev Med Hyg. 2012;53:181–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Platteau T, Wouters K, Apers L, Avonts D, Nöstlinger C, Sergeant M, et al. Voluntary outreach counselling and testing for HIV and STI among men who have sex with men in Antwerp. Acta Clin Belg. 2012;67:172–6. doi: 10.2143/ACB.67.3.2062651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Scott C, Day S, Low E, Sullivan A, Atkins M, Asboe D. Unselected hepatitis C screening of men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. J Infect. 2010;60:351–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Boot HJ, Hahné S, Cremer J, Wong A, Boland G, Van Loon AM. Persistent and transient hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in children born to HBV-infected mothers despite active and passive vaccination: perinatal HBV transmission. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:872–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Bracciale L, Fabbiani M, Sansoni A, Luzzi L, Bernini L, Zanelli G. Impact of hepatitis B vaccination in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers: a 20-year retrospective study. Infection. 2009;37:340–3. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Hahné S, van den Hoek A, Baayen D, van der Sande M, de Melker H, Boot H. Prevention of perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission in the Netherlands, 2003-2007: children of Chinese mothers are at increased risk of breakthrough infection. Vaccine. 2012;30:1715–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Eurostat. Migration and migrant population statistics. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics. Accessed: May 4, 2015.

- 158.Rossi C, Shrier I, Marshall L, Cnossen S, Schwartzman K, Klein MB, et al. Seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and prior immunity in immigrants and refugees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. ECDC technical report: assessing the burden of key infectious diseases affecting migrant populations in the EU/EEA. Stockholm: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Vriend HJ, Van Veen MG, Prins M, Urbanus AT, Boot HJ, Op De Coul EL. Hepatitis C virus prevalence in the Netherlands: migrants account for most infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:1310–7. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Roux P, Sagaon-Teyssier L, Lions C, Fugon L, Verger P, Carrieri MP. HCV seropositivity in inmates and in the general population: an averaging approach to establish priority prevention interventions. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005694. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.