Abstract

Background

Prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders (AMDs) in HIV-infected individuals has varied widely due to the variety of measurements used and differences in risk factor profiles between different populations. We aimed to examine the relationship between HIV-status and hospitalisation for AMDs in GBM.

Design and Methods

HIV-infected (n=557) and -uninfected (n=1325) GBM recruited in Sydney, Australia were probabilistically linked to their hospital admissions and death notifications (2000–2012). Random-effects Poisson models were used to assess risk factors for hospitalisation. Cox regression methods were used to assess risk factors for mortality.

Results

We observed 300 hospitalisations for AMDs in 15.3% of HIV-infected and 181 in 5.4% of -uninfected participants. Being infected with HIV was associated with a 2 and a half fold increase in risk of hospitalisation for AMDs in GBM. Other risk factors in the HIV-infected cohort included previous hospitalisation for HIV-related dementia, a more recent HIV-diagnosis and a CD4 T-cell count above 350/mm3. Being hospitalised for an AMD was associated with a 5 and a half fold increased risk of mortality, this association did not differ by HIV status. An association between substance use and mortality was observed in individuals hospitalised for AMDs.

Conclusions

There is a need to provide more effective strategies to identify and treat AMDs in HIV-infected GBM. This research highlights the importance of further examination of the effects of substance use, neurocognitive decline and AMDs on the health of HIV-infected individuals.

Keywords: HIV, mental health, mortality, hospitalization, homosexuality, male

Introduction

As numbers of HIV-infected individuals initiating combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) increase1,2 and life-span of HIV-infected individuals increases3,4, there is an immediate need to accelerate research addressing comorbidities in HIV-infection. Anxiety and mood disorders (AMDs) are some of the most common comorbidities occurring among HIV-infected individuals5,6. They are known to have serious implications for the clinical management of HIV-infection7–11, likely, in part, through contributing to poor adherence to cART12. It is also known from population-based samples that AMDs are associated with the clinical progression of other (non-HIV) diseases, such as cardiovascular disease13,14, pulmonary disease15 and dementia16, which are known to be more prevalent in HIV-infected cohorts17–19. While limited research has directly quantified the added burden of AMDs in HIV-infected individuals to risk of serous non-AIDS events some recent findings do support this likelihood20.

While generally high, reported prevalence of AMDs in HIV-infected individuals have varied widely, likely due to the variety of measurements used and differences in risk factor profiles between different populations. There is evidence from population-based surveys of gay and bisexual men (GBM) that they experience higher rates of AMDs than their heterosexual counterparts27–30. Thus it is likely that GBM are at greater risk for AMDs, independent of HIV status. However, failure to identify appropriate HIV-uninfected control groups to measure the independent effect of HIV on risk of AMDs could lead to biased results.

AMDs in HIV-infected individuals also have public health importance, through their association with increased HIV transmission behaviours21,22 and through the costs associated with high rates of hospitalisation. Psychiatric diagnoses were the leading cause of hospitalisation (28,233/214,845) in a cohort of HIV-infected US Veterans and were significantly more prevalent than in uninfected veterans23. Psychiatric hospitalisations were the fourth most common reason for admission (444/5,593) in a cohort of HIV-infected persons engaged in care in the US between 2005–201124. While in a French prospective HIV-infected cohort, chronic depression at baseline was associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of all-cause hospitalisation (odds ratio: OR 3.8, 95%CI 1.0–14.9)25. Furthermore, psychiatric diagnoses in HIV-infected individuals have been shown to be associated with high readmission rates. In a prospective cohort of patients engaged in HIV care (2005–2010), psychiatric admissions were the fifth most frequent diagnostic category and were associated with a 17% readmission rate (exceeding the readmission rate of 13.3% for US adults)26.

In this study, we aimed to examine the relationship between HIV-status and hospitalisation for AMDs in GBM. We also aimed to assess whether hospitalisation for AMDs was predictive of mortality in GBM and whether this differed by HIV-infection status.

Methods

We conducted a record linkage study, linking two cohorts of HIV-infected (n=557) and -uninfected (n=1325) GBM recruited in Sydney, New South Wales (NSW), Australia with their respective hospital admissions and death notifications.

Study population

Our study cohorts included participants recruited to the Positive Health (pH) (HIV-infected) and Health in Men (HIM) (HIV-uninfected) studies. Both studies have been described in detail elsewhere32,33. Briefly, men were recruited using similar community-based methods and participants were interviewed face-to-face annually. Enrolment in pH occurred from 1998 to 2006 and follow up ceased in 2007. Enrolment in HIM occurred from 2001 to 2004 and active follow-up ceased in 2007. The serostatus of participants in both cohorts was confirmed by serological testing at intake and in HIV-uninfected participants through annual testing thereafter. All participants in both studies either had sexual contact with at least one man during the previous 5 years or self-identified as gay, homosexual, queer or bisexual. In both studies the majority of participants identified as gay, homosexual or queer34,35. Data collected common to both studies included demographics, sexual and drug use behaviour, STIs and STI testing, gay community involvement, general self-reported health and use of health care services.

Registries and Data linkage

Probabilistic linkage methods36 were used to link individuals in pH and HIM to the data sources described below.

The NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC) includes all inpatient admissions from all public (including psychiatric), private and repatriation hospitals, private day procedure centres and public nursing homes in NSW. Diagnosis and procedure fields are coded according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Disease-Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM). Patient name has only been recorded since 1 July 2000, so we restricted analysis to admissions from 1 July 2000 to the most recent available data at time of analysis (30 June 2012).

The Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (RBDM) which reports fact of death was used to censor person-years of observation and was available for January 1998 to June 2013. While the Australian Bureau of Statistics Mortality data (ABS) reports cause of death coded according to ICD-10-AM but was only available for the period from January 1998 to Dec 2007.

The HIV administrative database is a register of HIV, notified to the Ministry of Health by laboratories, hospitals, and medical practitioners. In addition to annual serological testing in the HIM cohort, seroconversions were identified through linkage of participants to the HIV registry. Data was available for the period from January 1998 to Dec 2012.

First name, surname, address, postcode, date of birth and date of last contact were used to probabilistically link participants to the APDC, RBDM and ABS registries using ChoiceMaker software (ChoiceMaker Technologies Inc., New York, US). Deterministic linkage was used to link participants to the HIV/AIDS notifications using two-character surname and given name codes, date of birth, sex and postcode. Linkage was conducted by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL), independent of the study investigators. Full details of the linkage process are outlined at (http://www.cherel.org.au/how-record-linkage-works). The probabilistic linkage of the cohorts had extremely high sensitivity and specificity (both 99.5%, 95%CI: 99.3–99.7%), as reported by CHeReL, which was determined by clerical review of matched and non-matched records37.

Individual consent for data linkage was collected in addition to consent to participate in the study. Only data from participants who consented to data linkage were included in this analysis (93% of HIM and 74% of pH participants). We found no significant differences in examined cohort characteristics between those that consented compared with those that declined linkage. Ethics approval was granted by the University of NSW and the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee.

Hospital Admissions for Anxiety- and Mood-disorders

A hospital admission was defined as an episode of care ending with hospital discharge, death or transfer to another type of care. Duplicate and nested hospital admissions were excluded (n=55) to ensure only one principal diagnostic code was recorded for each admission. Hospital admissions for anxiety-disorders were defined as admissions with a principal or secondary ICD-10 diagnosis code of phobic anxiety disorders (F40), other anxiety disorders (F41), obsessive-compulsive disorders (F42), reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders (F43), dissociative disorders (F44), somatoform disorders (F45), and other neurotic disorders (F48). Hospital admissions for mood-disorders were defined as admissions with a principal or secondary ICD-10 diagnosis code of manic episode (F30), bipolar affective disorder (F31), depressive episode (F32), recurrent depressive disorder (F33), persistent mood disorders (F34), other mood disorders (F38) and unspecified mood disorder (F39)38.

Statistical Methods

Time at risk commenced at entry into the study cohort or the opening of database for hospital admissions (1 July 2000), whichever was latest. Incidence rates of events were determined using person-years (PYs) methods with data right censored at death or the close of hospital database (31 December 2012). Data from HIV-uninfected participants who seroconverted (n=51) were excluded from analysis.

The number of hospitalisations for AMDs in the cohorts were compared with the expected number using rates for the Australian male population39 and summarized as standardised incidence ratios (SIRs). SIRs were adjusted for age and year of admission. To adjust for correlation between hospitalisations in the same individual, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the SIRs were calculated using the method by Stukel et al.40.

Risk factors for hospitalisations for AMDs were assessed using random-effects Poisson regression methods. The multivariate model was determined using a backwards step-wise approach with a two-sided statistical significance (p<0.05) with an inclusion p-value of 0.10. The following covariates were considered as fixed effects (reported at entry into the cohort): country of birth, ethnicity, education, employment, income, religion, STI exposure (excluding HIV), hepatitis C exposure, general health and use of mental health services, frequency of exercise, smoking and alcohol consumption, recreational and injecting drug use, number of male partners in the previous 6 months, reported condomless anal intercourse, experiences of discrimination and harassment, gay community involvement, living arrangements, current partnership status and partners’ HIV serostatus. Age was included as a time-updated variable. The interactions between risk factors and HIV status were tested, if a significant association was found then stratified results were presented for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected GBM. In addition to risk factors for both cohorts, a number of HIV-related risk factors were assessed in the HIV-infected cohort alone. All were measured at entry into the cohort unless otherwise stated and were adjusted for risk factors found to be significantly associated with both cohorts. HIV-infected only risk factors included previous hospitalisation for HIV-related dementia (time-updated), use of cART, nadir CD4 T-cell count and recent CD4 T-cell count, recent viral load, frequency of viral load and CD4 testing, previous hospitalisation for HIV-related illness, year diagnosed HIV-infected, adherence to cART, and perceived emotional support. The log-likelihood ratio statistic was used to assess contribution to the model. Missing data were included in the analysis as a separate category.

We determined cause of death either through linkage to the ABS, if available, or through the admitting diagnoses if cause of death was unavailable from ABS and the death occurred in hospital. Otherwise if both of these were unavailable, cause of death was reported as missing. Time-updated hospitalisation for AMDs was assessed as a risk factor for mortality using Cox regression methods and was adjusted for other significant risk factors for mortality. Other significant risk factors were determined using backwards step-wise approach with a two-sided statistical significance (p<0.05) and an inclusion p-value of 0.10. Assessment of residuals showed no evidence of violation of proportional hazards assumptions.

Chi square test (χ2) was used to analyse categorical variables and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. Analyses were performed using STATA (version 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

1,882 participants were included in the analysis; 557 HIV-infected and 1,325 HIV-uninfected GBM. At baseline, HIV-infected and -uninfected participants had a median age of 41yrs (IQR 36–47) and 35yrs (30–42), respectively (Table 1). Sixty percent of HIV-infected and 73.6% of -uninfected men had attained tertiary education. Illicit drug use was common; over 80% of participants in both cohorts reporting illicit drug use in the last 6 months. Sixty percent (60.1%) of HIV-infected participants compared with 1.4% of HIV-uninfected participants scored highly on psychological distress. Of the HIV-infected participants, 44.7% reported a recent CD4 above 500 cells/mm3, 74.2% were receiving cART and 76.7% were diagnosed pre-HAART era.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in HIV-infected and –uninfected gay and bisexual men recruited in Sydney, Australia

| HIV-uninfected cohort (n=1325) (%) |

HIV-infected cohort (n=557) (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 35.3 (29.6–42.0) | 40.9 (36.0–46.7) |

| Ethnicity: Anglo-Australian/ Anglo-Celtic | 985 (74.3) | 424 (76.1) |

| Country of birth: Australia | 913 (68.9) | 392 (70.4) |

| Education: Tertiary | 975 (73.6) | 334 (60.0) |

| Employment:Unemployed or Receiving Pension/Disability Pension | 83 (6.3) | 216 (38.8) |

| Income: <500 per week/ <26,000 per year | 266 (20.1) | 267 (47.9) |

| Sexual Identity: | ||

| Gay, queer or homosexual | 1088 (95.2) | 443 (92.1) |

| Bisexual | 42 (3.7) | 17 (3.5) |

| Other | 9 (0.8) | 21 (4.4) |

| Exposed to Hepatitis C | 52 (3.9) | 69 (12.4) |

| Daily Smoker | 420 (31.7) | 292 (52.42) |

| Number of Alcoholic drinks consumed in one sitting (on average) | ||

| 5 to 8 | 242 (18.3) | 68 (12.2) |

| >9 | 62 (4.7) | 31 (5.6) |

| Illicit Drug Use (past 6 months)* | 1061 (80.1) | 481 (86.4) |

| Injected drugs in last 6months | 50 (3.8) | 89 (16.0) |

| Any unprotected anal intercourse (past 6 months) | 832 (62.8) | 141 (25.3) |

| Kessler Score of Psychological Distress: | 19 (1.4) | 335 (60.1) |

| High (20–30) | 19 (1.4) | 335 (60.1) |

| Mild to Moderate (12–19) | 313 (23.6) | 43 (6.1) |

| Low (6–11) | 989 (74.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Year diagnosed HIV Positive: | ||

| 1980–1996 | 427 (76.7) | |

| 1996–2006 | 118 (21.2) | |

| Last CD4 cell count: | ||

| <350 | 143 (25.7) | |

| 351–500 | 105 (18.9) | |

| Over 500 | 249 (44.7) | |

| Antiretroviral Therapy History: | ||

| never taken | 87 (15.6) | |

| currently taking | 413 (74.2) | |

| past but now stopped | 47 (8.4) |

includes amyl nitrate, cannabis, cocaine, meth/amphetamines, MDMA or other MDA, psychedelics, hallucinogens, downers (barbiturates, tranquilisers or sedatives), Rohypnol or ketamine, heroin or other opiates and GHB.

Abbreviations: N, Number; IQR, Interquartile Range; ml, millilitres;

We observed 300 hospital admissions for AMDs in 85 (15.3%) HIV-infected participants and 181 hospital admissions for a AMDs in 72 (5.4%) HIV-uninfected participants (Table 2). A significantly greater proportion of HIV-infected compared to -uninfected participants were admitted for an AMD (p-value<0.001). Hospitalisation rates with a primary diagnosis of a AMDs were 9.7 times higher in the HIV-infected cohort [9.73 (5.35–17.67)] and 3.3 times higher in the HIV-uninfected cohort [SIR 3.33 (95% CI 2.20–5.03)] compared with rates reported in the Australian male population. Frequency of readmissions were slightly higher in the HIV-infected cohort but this did not reach statistical significance (p-value=0.061).

Table 2.

Description of hospitalisations for anxiety and mood disorders in HIV-infected and –uninfected gay and bisexual men, 2000–2012

| HIV-uninfected Cohort | HIV-infected Cohort | P-value for Cohort Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 1325 | 557 | |

| Total Follow-up Time, years | 13025 | 5580 | |

| Crude Rate of Hospital Admissions for Mood and/or Anxiety-disorders, per 100 Pys (95% CI) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 5.4 (4.8–6.0) | <0.001 |

| Number of Hospital Admission for a Mood and/or Anxiety-disorder | 181 | 300 | |

| Number of Mood Hospitalisations, N (%) | 131 (72.4) | 228 (76.0) | |

| Number of Anxiety Hospitalisations, N (%) | 34 (18.8) | 56 (18.7) | |

| Number of Both Mood and Anxiety Hospitalisations, N (%) | 16 (8.8) | 16 (5.3) | |

| Number of Participants with a Hospital Admission for Mood and/or Anxiety-disorder | 72 (5.4) | 85 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Number of participants with a readmission, N (%) | 29 (40.3) | 40 (55.3) | 0.061 |

| Crude Rate of Hospital Admissions for a Mood and/or Anxiety-disorder resulting in transfer to a Psychiatric Ward, N (%) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 0.011 |

| Median Length of Stay per AMDs admission, days (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–7.0)× | 5.0 (2.0–12.0)‡ | <0.001 |

| Median Length of Stay per other (non-AMDs) admission, days (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0)× | 2.0 (1.0–5.0)‡ | <0.001 |

| General population comparison: | |||

| Standardized Incidence Ratio (95%CI)† | 3.33 (2.20–5.03) | 9.73 (5.35–17.67) |

General population comparison only for primary diagnoses, adjusted for age and year of diagnosis

p-value for comparison <0.0001

p-value for comparison <0.0001

Significant correlates for hospitalisation for AMDs included having HIV [IRR 2.49 (95%CI 1.47–4.21)], being unemployed [2.41 (1.41–4.12)], identifying as bisexual or other compared with gay, queer or homosexual [5.24 (2.34–11.74)], being religious [2.21 (1.40–3.49)], having previously sought counselling for mental health [4.25 (2.96–8.27)], and being a daily smoker [1.94 (1.22–3.08)] (Table 3). Drinking at low levels (1–2 drinks in a sitting) compared with being a non-drinker was found to be protective [IRR 0.36 (95%CI 0.15–0.87)]. A higher score of psychological distress was associated with hospitalisation for AMDs but was excluded due to its’ high correlation with HIV status (data not shown). Age was found to significantly interact with HIV status (p-value<0.0001; see Supplemental Digital Content Appendix A). There was an association between being older (45 and above compared with 18–35 years) and a greater likelihood of hospitalisation for AMDs in the HIV-infected but not the HIV-uninfected cohort.

Table 3.

Risk factors for hospitalisation for anxiety and mood disorders in HIV-infected and –uninfected gay and bisexual men

| Variable | Level | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | PYs | Rate p. 100 Pys (95%CI) | IRR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| HIV status‡ | HIV-uninfected | 181 | 13025 | 1.39 (1.20–1.61) | 1 | ||

| HIV-infected | 300 | 5580 | 5.38 (4.80–6.02) | 2.49 | 1.47–4.21 | 0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Age, years§‡ | 18–35 | 54 | 4128 | 1.31 (1.00–1.71) | 1 | ||

| 36–45 | 153 | 6949 | 2.20 (1.88–2.58) | 1.45 | 0.99–2.11 | ||

| 46–55 | 202 | 5177 | 3.90 (3.40–4.48) | 2.36 | 1.50–3.72 | ||

| 55+ | 72 | 2349 | 3.06(2.43–3.86) | 1.99 | 1.15–3.46 | 0.0015 | |

|

| |||||||

| Employment | Employed | 218 | 14308 | 1.52 (1.33–1.74) | 1 | ||

| Unemployed | 252 | 3906 | 6.45 (5.70–7) | 2.41 | 1.41–4.12 | 0.005 | |

|

| |||||||

| Sexual identity | Gay, queer or homosexual | 414 | 17519 | 2.36 (2.15–2.60) | 1 | ||

| Bisexual /Other | 67 | 1085 | 6.17 (4.86–7.84) | 5.24 | 2.34–11.74 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Religious belief | No | 194 | 10100 | 1.92 (1.67–2.21) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 280 | 8248 | 3.39 (3.02–3.82) | 2.21 | 1.40–3.49 | 0.003 | |

|

| |||||||

| Reported as having sought counselling for mental health in previous 12 months | No | 154 | 13437 | 1.15 (1.00–1.34) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 326 | 5150 | 6.33 (5.68–7.06) | 4.25 | 2.96–8.27 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Daily Smoker | No | 163 | 11158 | 1.46 (1.25–1.70) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 297 | 7063 | 4.21 (3.75–4.71) | 1.94 | 1.22–3.08 | 0.006 | |

|

| |||||||

| Number of Alcoholic drinks consumed in one sitting (on average) | Non-drinker | 65 | 1210 | 5.37 (4.21–6.84) | 1 | ||

| 1 or 2 | 139 | 5915 | 2.35 (1.99–2.77) | 0.36 | 0.15–0.87 | ||

| 3 or 4 | 158 | 7324 | 2.16 (1.85–2.52) | 0.69 | 0.28–1.68 | ||

| 5 to 8 | 62 | 3052 | 2.03 (1.58–2.61) | 0.63 | 0.23–1.72 | ||

| >9 | 52 | 909 | 5.72 (4.36–7.50) | 1.66 | 0.50–5.50 | 0.021 | |

|

| |||||||

|

Only tested in the HIV-infected cohort

| |||||||

| Previously hospitalised for HIV-related dementia§† | No | 224 | 5439 | 1.42 (3.61–4.69) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 76 | 140 | 54.18 (43.27–67.84) | 3.08 | 1.78–5.30 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Year diagnosed HIV positive† | 1980–1985 | 59 | 1570 | 3.57(2.91–4.85) | 1 | ||

| 1986–1991 | 115 | 1602 | 7.18 (5.98–8.62) | 1.92 | 0.98–7.22 | ||

| 1992–1996 | 37 | 1292 | 2.86 (2.07–3.95) | 1.93 | 0.98–8.56 | ||

| 1996–2006 | 82 | 1012 | 8.10 (6.52–10.06) | 2.40 | 1.29–12.15 | 0.025s | |

|

| |||||||

| Self-reported CD4 T-cell count† | <350 | 160 | 1404 | 11.40 (9.76–13.31) | 1 | ||

| 351–500 | 30 | 1043 | 2.88 (2.01–4.11) | 0.20 | 0.07–0.56 | ||

| 501–750 | 61 | 1360 | 4.48 (3.49–5.76) | 0.33 | 0.13–0.85 | ||

| over 750 | 33 | 1183 | 2.79 (1.98–3.92) | 0.23 | 0.08–0.63 | 0.004 | |

Time-updated

Significant age and HIV status interaction, p-value<0.0001

Only tested in HIV-infected cohort, adjusted for age, employment, sexual identity, religious belief, prior counselling for mental health, smoking, alcohol consumption and other significant HIV-related risk factors

significant linear trend

Abbreviations: p. 100Pys= per 100 person-years, 95%CI=95% Confidence Intervals, IRR=Incidence Rate Ratio

In the HIV-infected cohort, previous hospitalisation for HIV-related dementia was shown to be significantly related to hospitalisations for AMDs [IRR 3.08 (95%CI 1.78–5.30)], as was a more recent HIV diagnosis [linear trend p-value=0.025]. Compared with having a CD4 T-cell count below 350/mm3, having a count above 350/mm3 at baseline was associated with fewer hospitalisations for AMDs [CD4 cell count 351–500: IRR 0.20 (95%CI 0.07–0.56); 501–750: 0.33 (0.13–0.85); over 750: 0.23 (0.08–0.63)].

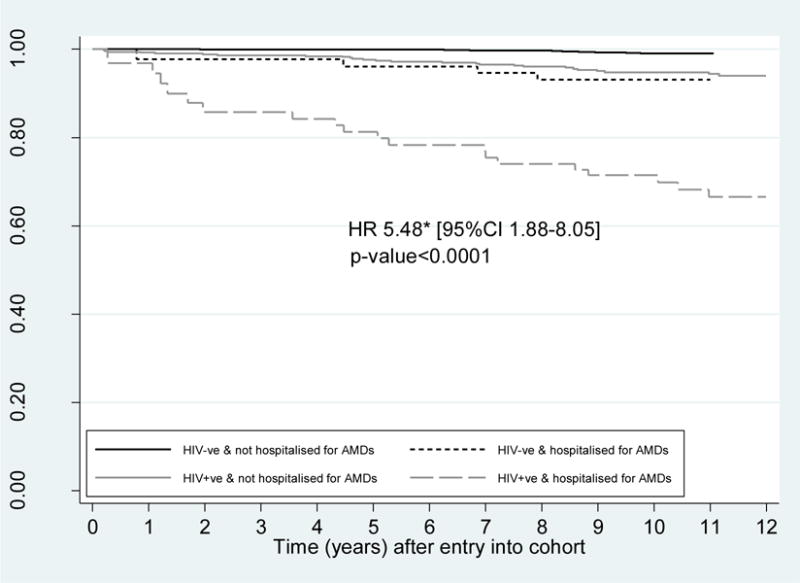

There were 46 deaths in the HIV-infected cohort and 14 deaths in the -uninfected cohort. In participants hospitalised for an AMD there were 19 deaths in HIV-infected and 4 deaths in –uninfected cohort. After adjusting for other risk factors, being hospitalised for a AMD was associated with a 5 and a half fold increased risk of mortality [HR 5.48 (95%CI 1.88–8.05)] (Figure 1). This association did not differ by HIV status (p-value for interaction=0.5275). Underlying causes of death were primarily for AIDS-related reasons in the HIV-infected cohort (63.2%) (Supplemental Digital Content Appendix B). Chronic alcohol use or liver failure due to alcohol use was listed as the primary cause of death for 2 (10.5%) HIV-infected and 1 (25.0%) -uninfected participants hospitalised for AMDs. Further alcohol use was listed as a secondary cause of death in an additional 6 (31.6%) HIV-infected participants hospitalised for AMDs (data not shown). Apart from one accidental death recorded in the -uninfected cohort, no other accidental deaths or suicides were reported.

Figure 1.

Survival curve by time-updated hospitalisation for a anxiety or mood disorders in HIV-infected and -uninfected gay and bisexual men, 2000–2012

*Test of interaction between HIV status and hospitalisation for mood/anxiety disorders and mortality was not significant (p-value=0.5275). HR adjusted for age, employment, weekly income, smoking, recreational drug use, injecting drug use, hepatitis C status, and partnership status; Abbreviations: HIV+ve=HIV-infected GBM, HIV-ve=HIV-uninfected GBM, AMDs=Anxiety and Mood Disorders

Discussion

In this study, HIV-infected GBM had a higher rate of hospitalisation for AMDs compared with estimates derived from the general population and rates seen in the -uninfected cohort. After adjusting for other risk factors, being infected with HIV was associated with a 2 and a half fold increase in risk of hospitalisation for AMDs in GBM. A 3 fold higher incidence of hospitalisation for AMDs was also seen in the HIV-uninfected GBM cohort compared to the general population. Our findings suggest that that the higher prevalence of AMDs that have been reported in GBM and HIV-infected populations is valid and has translated into higher rates of hospitalisation seen in both of these groups.

Previous research of AMDs in HIV-infected populations has been hindered by the inability to distinguish between the contribution of HIV and the socio-behavioural factors common to HIV-infected populations. Populations at greatest risk for HIV infection often have a high prevalence of (pre-existing) AMDs thereby confounding comparisons with the general population. In this study we were able to adjust for potential confounding through both restricting our analyses to GBM and administering detailed behavioural and demographic questionnaires. Our findings suggest a clear association between AMDs and being HIV-infected, whether this is a direct effect of the HIV virus or an effect of being infected with a life-long comorbid illness is still difficult to ascertain.

Other risk factors for hospitalisation included sexual identity. Identifying as ‘bisexual or other’ compared to identifying as ‘gay, queer or homosexual’ was found to be significantly associated with hospitalisation for AMDs in both cohorts, supporting research showing a higher burden of mental health problems in bisexual people41–43. Not surprisingly having previously sought counselling for mental health was also associated with hospitalisation for AMDs. Sixty eight percent of hospitalisations occurred in individuals who had previously sought counselling for mental health, suggesting a significant need to better manage AMDs in this population. Links between HIV and mental health services are encouraged though the National HIV Strategy in Australia44. However, a review by NSW Health found that while contact between services existed, they were not formalised, thus making them vulnerable45. There is a strong need to develop formal legislation which could provide a basis for more coordinated efforts between HIV and mental health services.

Older HIV-infected GBM in our cohort did not experience the decline in hospitalisation for AMDs that has been observed in the general population46 and was observed in the HIV-uninfected cohort in this study. The HIV-infected cohort demonstrated a two fold increase in risk of hospitalisation for AMDs in the older age groups (46–55, 55+) compared with the youngest age group (18–35). The physical and mental challenges of aging with HIV are well documented47–49, though few prevalence studies of psychopathology have included a substantial number of older HIV-infected individuals. Two studies have previously demonstrated no significant decrease in rates of depression with increasing age among HIV-infected individuals50,51; however both had small sample sizes. This is the first study that is known to the authors which suggests AMDs may increase with age in HIV-infected individuals.

Previous hospitalisation for dementia was associated with an increased likelihood of hospitalisation for AMDs in the HIV-infected cohort, suggesting that neurocognitive decline and mental illness may be associated. There is some epidemiological evidence to suggest that depression and dementia frequently co-occur and both may be associated with inflammatory changes in the brain52,53. It is possible that advanced HIV and HIV encephalopathy may cause AMDs in HIV-infected individuals. It is also possible that causality may have gone in the other direction that AMDs act as a risk factor for neurocognitive impairment. Or perhaps the difficulties in discerning psychiatric disorders from cognitive dysfunction resulted in delays in the diagnosis of both. Clearly there is a strong need for prospective longitudinal study designs which could provide data on the mechanisms of progression of neurocognitive impairment (both AMDs and dementia), how neurocognitive impairment varies as a function of HIV disease stage, and the role of potential co-factors and mediators of progression of HIV neurocognitive impairment in aging HIV-infected populations.

HIV-infected individuals more recently diagnosed also had increased likelihood of hospitalisation for AMDs, suggesting that both periods early in diagnosis and later in infection could be associated with an increased risk for AMDs. The prospective longitudinal cohort, Steps, found depression was highly prevalent in newly diagnosed HIV-infected persons in the US54. There are several factors which could predispose HIV-infected individuals to be more susceptible to AMDs early in diagnosis, including the traumatic nature of being diagnosed with a disease that is chronic and often perceived as life-threatening; the relatively high rates of traumatic exposures that have been reported in studies of persons with HIV/AIDS, and patient perceptions of AIDS-related stigma55–57. These results provide further evidence of the need for enhanced linkage between HIV testing and mental health services.

Interestingly, the strong effect of hospitalisation for AMDs on mortality was not seen to be significantly different for HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected GBM, despite an overall increased risk of hospitalisation in the HIV-infected individuals. Despite substance use not presenting as a risk factor for hospitalisation for AMDs (with low alcohol use actually coming up as protective compared to non-use) there was, however, a strong link between substance use and mortality in individuals hospitalised for AMDs. Substance use was listed as the cause of death in 42% of deaths in the HIV-infected cohort previously hospitalised for AMDs. This supports previous literature which has documented a high frequency of comorbid psychiatric and drug dependence disorders in HIV-infected and GBM cohorts58,59. Unfortunately small numbers of deaths makes it difficult to make robust interpretations from this data however it highlights the need for further research investigating the role of AMDs and substance use in the mortality of HIV-infected individuals.

There are some limitations of our research. Consistent with other registry linkage studies, error could have arisen from participant migration outside of the registry region. Unfortunately it is impossible to estimate the impact of this on missing linkages as relevant linkage validation subsets with known outcomes were not available. Furthermore we were unable to examine psychiatric care received outside a hospital setting in either group. It is possible that differences in access to care could have impacted rates of hospitalisation seen in this study. Certainly it is likely that the HIV-infected cohort would be more greatly integrated into medical follow-up in the general practice setting, which was on post-hoc examination supported by our data (22% of HIV-uninfected had no regular doctor vs. 2% of HIV-infected GBM). Whether or not this would impact participants’ likelihood of seeking psychiatric care in a hospital setting is unknown. All residents in Australia have access to Medicare which enables them to receive hospital care free of charge; however discrimination and stigma and poorer health seeking behaviour could have contributed to lower hospital rates seen in the HIV-uninfected cohort.

Further, we were unable to exclude GBM from the general population estimates. However, the proportion of men identifying as gay or bisexual is low in the general Australian male population (1.6 and 0.9% respectively)60 and would only have biased our estimates towards the null. While method of recruitment in both cohorts was similar and is a strength of the study, the representativeness of the cohort to the wider HIV-infected and -uninfected homosexual population is unknown. Representative samples of gay and other homosexually active men are impossible to attain as the population cannot be enumerated (24). Despite these limitations, investigation of baseline characteristics in both cohorts showed similarity to those described in other cohorts of HIV-infected and -uninfected GBM in Australia (39). Further, recruitment for both cohorts ceased in 2006 thus findings may not be able to be extrapolated to more recently diagnosed men who have only been exposed to newer drug regimens.

Conclusions

This research highlights the importance of providing more effective strategies to identify and treat AMDs in HIV-infected GBM, particularly in aging HIV-infected populations. Our findings suggest that treatment of AMDs in HIV-infected GBM could reduce the burden on hospital services and possibly avert needless deaths. Furthermore, our research suggests the importance of further examination of the independent and joint effects of substance use, neurocognitive decline and AMDs on health outcomes in HIV-infected individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants, the dedicated pH and HIM study teams and the participating doctors and clinics for their contribution to the HIM and pH studies. The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the New South Wales Centre for Health Record Linkage in the conduct of this study.

Source of Funding: The Kirby Institute and the Centre for Social Research in Health, UNSW Australia are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The Health in Men Cohort study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, a component of the USA Department of Health and Human Services (NIH/NIAID/DAIDS: HVDDT Award N01-AI-05395), the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia (Project grant #400944), the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (Canberra) and the New South Wales Health Department (Sydney). The Positive Health Cohort study was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (Canberra) and the New South Wales Health Department (Sydney). HF Gidding is supported by an NHMRC Postdoctoral Research Fellowship. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the view of any of the institutions mentioned above.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial, consultant, institutional or other relationships that might lead to bias or conflict of interest for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocroft A, Vella S, Benfield TL, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. The Lancet. 1998 Nov 28;352(9142):1725–1730. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining Morbidity and Mortality among Patients with Advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vance DE, Mugavero M, Willig J, Raper JL, Saag MS. Aging With HIV: A Cross-Sectional Study of Comorbidity Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics Across Decades of Life. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2011;22(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Dec 15;45(12):1593–1601. doi: 10.1086/523577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans DL, Ten Have TR, Douglas SD, et al. Association of depression with viral load, CD8 T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;159(10):1752–1759. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pence BW, Miller WC, Gaynes BN, Eron JJ., Jr Psychiatric illness and virologic response in patients initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2007 Feb 1;44(2):159–166. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c2f51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazo M, Gange SJ, Wilson TE, et al. Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: longitudinal study of men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Nov 15;45(10):1377–1385. doi: 10.1086/522762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heywood W, Lyons A. HIV and Elevated Mental Health Problems: Diagnostic, Treatment, and Risk Patterns for Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in a National Community-Based Cohort of Gay Men Living with HIV. AIDS and behavior. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Kumar M, et al. Psychosocial and Neurohormonal Predictors of HIV Disease Progression (CD4 Cells and Viral Load): A 4 Year Prospective Study. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(8):1388–1397. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0877-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMatteo M, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007 Jul;22(7):613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Player MS, Peterson LE. Anxiety disorders, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;41(4):365–377. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.4.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikkelsen RL, Middelboe T, Pisinger C, Stage KB. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2004;58(1):65–70. doi: 10.1080/08039480310000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessing LV. Depression and the risk for dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012 Nov;25(6):457–461. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328356c368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crothers K, Butt AA, Gibert CL, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Crystal S, Justice AC. Increased COPD among HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative Veterans*. Chest. 2006;130(5):1326–1333. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currier JS, Lundgren JD, Carr A, et al. Epidemiological evidence for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients and relationship to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Circulation. 2008 Jul 8;118(2):e29–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McArthur JC. HIV dementia: an evolving disease. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2004;157(1–2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White JR, Chang CH, So-Armah KA, et al. Depression and HIV Infection are Risk Factors for Incident Heart Failure Among Veterans: Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Circulation. 2015 Sep 10; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perdue T, Hagan H, Thiede H, Valleroy L. Depression and HIV risk behavior among Seattle-area injection drug users and young men who have sex with men. AIDS education and prevention: official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2003 Feb;15(1):81–92. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.81.23842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart TA, James CA, Purcell DW, Farber E. Social Anxiety and HIV Transmission Risk among HIV-Seropositive Male Patients. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2008;22(11):879–886. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rentsch C, Tate JP, Akgun KM, et al. Alcohol-Related Diagnoses and All-Cause Hospitalization Among HIV-Infected and Uninfected Patients: A Longitudinal Analysis of United States Veterans from 1997 to 2011. AIDS and behavior. 2015 Feb 26; doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowell TA, Gebo KA, Blankson JN, et al. Hospitalization Rates and Reasons Among HIV Elite Controllers and Persons With Medically Controlled HIV Infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2015 Jun 1;211(11):1692–1702. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dray-Spira R, Gueguen A, Persoz A, et al. Temporary employment, absence of stable partnership, and risk of hospitalization or death during the course of HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2005 Oct 1;40(2):190–197. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000165908.12333.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry SA, Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission rate among adults living with HIV. AIDS (London, England) 2013 Aug 24;27(13):2059–2068. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283623d5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakraborty A, McManus S, Brugha TS, Bebbington P, King M. Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2011 Feb;198(2):143–148. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003 Feb;71(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King M, McKeown E, Warner J, et al. Mental health and quality of life of gay men and lesbians in England and Wales: controlled, cross-sectional study. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2003 Dec;183:552–558. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Hughes M, Ostrow D, Kessler RC. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):933–939. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prestage G, Mao L, Kippax S, et al. Use of Viral Load to Negotiate Condom Use Among Gay Men in Sydney, Australia. AIDS and behavior 2009/08/01. 2009;13(4):645–651. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin F, Prestage GP, Mao L, et al. Transmission of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in a prospective cohort of HIV-negative gay men: the health in men study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2006 Sep 1;194(5):561–570. doi: 10.1086/506455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao L, Van De Ven PG, Prestage G, et al. Health in Men. Baseline data. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prestage G, Kippax SC, Grulich AE, Race K, Grierson JW, Song A. Positive Health: Method and Sample. Sydney, Australia: University of NSW; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaro MA. Probabilistic linkage of large public health data files. Statistics in medicine. 1995;14(5–7):491–498. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140510. Mar 15–Apr 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) Quality Assurance. 2015 http://www.cherel.org.au/quality-assurance. Accessed 27th August, 2015.

- 38.World Health Organization (WHO) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 39.AIHW, editor. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Hospital Morbidity Database 2011/12, Principal Dianosis. Canberaa: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stukel TA, Glynn RJ, Fisher ES, Sharp SM, Lu-Yao G, Wennberg JE. Standardized rates of recurrent outcomes. Statistics in medicine. 1994;13(17):1781–1791. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Rodgers B, Jacomb PA, Christensen H. Sexual orientation and mental health: results from a community survey of young and middle-aged adults. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2002 May;180:423–427. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross LE, Dobinson C, Eady A. Perceived determinants of mental health for bisexual people: a qualitative examination. Am J Public Health. 2010 Mar;100(3):496–502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tjepkema M. Health care use among gay, lesbian and bisexual Canadians. Health Rep. 2008 Mar;19(1):53–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Commonwealth of Australia. Seventh National HIV Strategy 2014–2017. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.HIV/AIDS care and treatment services needs assessment [electronic resource] Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Australian Social Trends: Using Statistics to Paint a Picture of Australian Society. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist. 2006 Dec;46(6):781–790. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin CP, Fain MJ, Klotz SA. The older HIV-positive adult: a critical review of the medical literature. Am J Med. 2008 Dec;121(12):1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyons A, Pitts M, Grierson J. Exploring the psychological impact of HIV: health comparisons of older Australian HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay men. AIDS and behavior. 2012 Nov;16(8):2340–2349. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rabkin JG, McElhiney MC, Ferrando SJ. Mood and substance use disorders in older adults with HIV/AIDS: methodological issues and preliminary evidence. AIDS (London, England) 2004 Jan 1;18(Suppl 1):S43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Atkinson JH, et al. Psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders among HIV-positive and negative veterans in care: Veterans Aging Cohort Five-Site Study. AIDS (London, England) 2004 Jan 1;18(Suppl 1):S49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korczyn AD, Halperin I. Depression and dementia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2009 Aug 15;283(1–2):139–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leonard BE, Myint A. Changes in the immune system in depression and dementia: causal or coincidental effects? Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(2):163–174. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.2/bleonard. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhatia R, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Graham J, Giordano TP. Persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and poor linkage to care: results from the Steps Study. AIDS and behavior. 2011 Aug;15(6):1161–1170. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9778-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breet E, Kagee A, Seedat S. HIV-related stigma and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected individuals: does social support play a mediating or moderating role? AIDS care. 2014;26(8):947–951. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.901486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brief DJ, Bollinger AR, Vielhauer MJ, et al. Understanding the interface of HIV, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use and its implications for health outcomes. AIDS care. 2004;16(Suppl 1):S97–120. doi: 10.1080/09540120412301315259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller AK, Lee BL, Henderson CE. Death anxiety in persons with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Death Stud. 2012 Aug;36(7):640–663. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.604467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chander G, Himelhoch S, Moore R. Substance Abuse and Psychiatric Disorders in HIV-Positive Patients. Drugs 2006/04/01. 2006;66(6):769–789. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holt M, Bryant J, Newman C, et al. Patterns of Alcohol and Other Drug Use Associated with Major Depression Among Gay Men Attending General Practices in Australia. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2012/04/01. 2012;10(2):141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith AM, Rissel CE, Richters J, Grulich AE, de Visser RO. Sex in Australia: sexual identity, sexual attraction and sexual experience among a representative sample of adults. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 2003;27(2):138–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.