Abstract

Background:

Dental caries and periodontal disease are most common oral diseases. Streptococcus mutans are considered to be the major pathogens in initiation of dental caries. Evidence shows that periodontal disease and caries share a number of contributory factors. Thus in view of these findings it would be worthwhile to examine whether Streptococcus mutans persist within the saliva and subgingival environment of the periodontitis patients and to determine whether there is any association between Streptococcus mutans colonization, pH of saliva and sub-gingival plaque pH in periodontal diseases before therapy.

Methods:

The study comprises of 75 subjects aged between 20-70 years, reporting to department of Periodontology, KLEs Institute of Dental Sciences, Bangalore. Subjects were divided into 3 groups of 25 each. Group 1 – Healthy controls, Group 2 – Gingivitis Group, 3 – Chronic periodontitis. Unstimulated saliva was collected in sterile container and immediately pH was evaluated. Subgingival plaque samples were collected from four deepest periodontal pockets in chronic periodontitis and from first molars in healthy subjects using 4 sterile paper points. In gingivitis subjects samples were collected from areas showing maximum signs of inflammation. All paper points and saliva samples were cultured on mitis salivarius agar culture media with bacitracin for quantification of the Streptococcus mutans colonies.

Results:

Increased colonization of Streptococcus mutans was seen in chronic periodontitis subjects both in saliva and sub-gingival plaque samples. There was also a positive correlation seen with the periodontal parameters.

Conclusion:

More severe forms of periodontal disease may create different ecological niches for the proliferation of Streptococcus mutans.

Keywords: Chronic periodontitis, pH, saliva, Streptococcus mutans

Introduction

Throughout life, all interfaces of the body are exposed to colonization by a wide range of microorganisms. In general, microbiota live in harmony with the host. Constant renewal of these surfaces by shedding prevents the accumulation of large masses of microorganisms. However, teeth provide hard nonshedding surfaces for the development of extensive bacterial deposits. The bacteria in the oral cavity remain within a specialized matrix called dental plaque or bacterial plaque. The accumulation and metabolism of the bacteria on hard oral surfaces is considered as the primary cause of dental caries, gingivitis, periodontitis, peri-implant infections, and stomatitis. Oral bacterial inhabit biofilms that form clusters adhering in layers to surfaces are not easily eliminated by immune responses and are resistant to antimicrobial agents. Dental plaque is one such biofilm.[1]

Periodontitis is a disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth whereas dental caries results from frequent exposure of teeth to low pH. These acidic conditions lead to the inhibition of acid-sensitive species and the selection of organisms with an aciduric physiology, such as Streptococcus mutans leading to dissolution of enamel.[2]

Evidence has suggested that both dental caries and periodontal diseases are multifactorial in nature and share a number of contributory factors that link them either directly or indirectly.[3]

There are studies suggesting no association between S. mutans count, gingival inflammation, periodontal pocket depth, and alveolar bone loss.[4]

However, recent studies have reported that untreated periodontitis patients have high recovery rates of S. mutans from saliva, tongue dorsum, buccal mucosa, and supra- and sub-gingival plaque.[5,6,7]

Given the high prevalence of root caries in periodontally treated patients with root exposure, it has been hypothesized that high levels of these cariogenic microorganisms may act as a predictor for the onset of carious lesions in these patients. Indeed, more root caries have been observed during the follow-up of periodontally treated patients with elevated counts of S. mutans than those with lower number of these microorganisms.[8]

In view of these findings, it remains unclear whether there is any correlation between the colonization of S. mutans and chronic periodontitis. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine whether there is any association between S. mutans, pH of saliva, subgingival plaque pH, and periodontal parameters in patients with varying degrees of periodontal disease before treatment.

Materials and Methods

Patient selection

The present study included 75 participants (range: 18–70 years) selected from the outpatient department of periodontics. Out of these, 25 cases were healthy individuals, 25 cases were diagnosed with generalized chronic gingivitis, and 25 cases were diagnosed with generalized chronic periodontitis. Healthy individuals were selected based on the absence of frank gingival inflammation, with no demonstrable attachment loss and probing depth >3 mm. Chronic periodontitis patients were selected as per the criteria laid down by the AAP 1999 classification and gingivitis patients selected showed signs of gingival inflammation and bleeding on probing with sulcus depth ≤3mm.[9]

All patients were systemically healthy and had not undergone periodontal therapy in the previous 6 months and antibiotic therapy in the previous 3 months. Smokers, patients on corticosteroids and chemotherapeutic agents, pregnant and lactating woman were excluded from the study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. After thorough explanation of the procedure, a written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Clinical parameters assessed for the study were plaque index (PI),[10] gingival index (GI),[11] probing pocket depth,[12] and clinical attachment level.

Method of collection of saliva and subgingival plaque sample

Saliva sample collection

All individuals were asked to refrain from eating or drinking for 1 h prior to sample collection. Unstimulated saliva samples were collected from each participant for duration of 2 min. The participants were asked to bend their head forward, and unstimulated saliva pooled in the floor of the mouth was collected into sterile-disposable bottles without deliberately expectorating into them. Approximately, 10 µl of the saliva samples was plated on culture plates comprising mitis salivarius agar culture media with bacitracin for quantification of the S. mutans colonies.[13]

The rest of the saliva sample was immediately subjected to pH analysis. The pH was analyzed using an electronic digital pH meter.[14]

Subgingival plaque samples

After careful removal of supragingival plaque, subgingival plaque samples in periodontitis patients were taken from four deepest periodontal pockets, one in each quadrant, using 1 sterile paper point per site. In gingivitis patients, sites showing maximum signs of gingival inflammation were selected for sample collection. Plaque samples from healthy participants were taken from the mesial aspect of all the four first molars. The paper points were transported in 2 ml reduced transport fluid media, vortexed for 30 s, and 10 µl of the solution was plated on mitis salivarius agar with bacitracin culture plates. All the culture plates were incubated for 48 h.[6]

The subgingival plaque pH measurement was performed with the new so-called “strip method” based on the usage of pH indicator strips (pH 2–10.5). Briefly, the strips were cut into 2 mm width and inserted subgingivally into the same four sites that were selected for plaque collection. The strips were inserted and kept for 10 s. The pH value of all the four sites was assessed by comparison of the color of the strip with the color index guide supplied by the manufacturer, and an average was considered.[15]

Statistical analysis

The three tests used for analysis of the results were Kruskal–Wallis test, Spearman's correlation test, and Wilcoxon-signed rank test.

Results

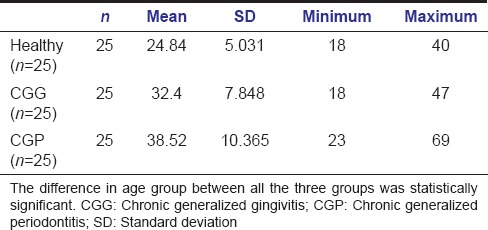

The study group comprised a total of 75 participants, categorized into three groups – healthy, gingivitis, and chronic periodontitis. The mean age of healthy individuals was 24.84 years, gingivitis group was 32.40 years, and chronic periodontitis group was 38.52 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of age between the three groups

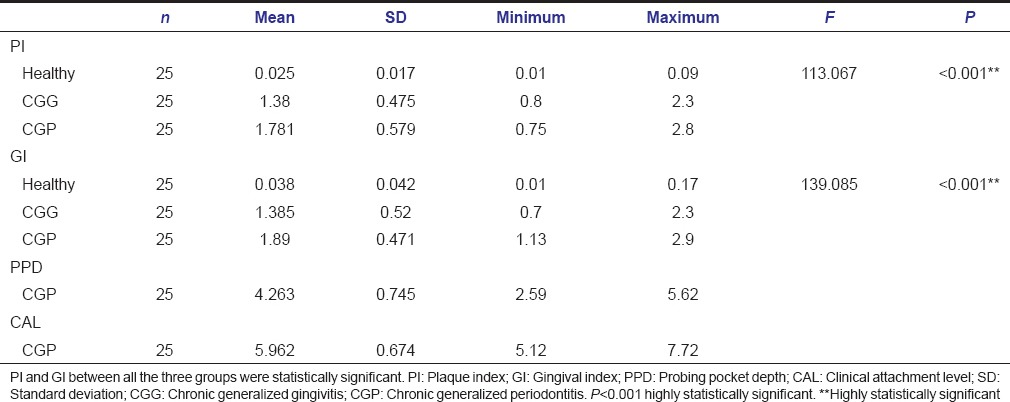

The mean PI of healthy individuals was 0.025, gingivitis patients was 1.380, and 1.781 in periodontitis patients. The mean GI was 0.038, 1.385, and 1.890 in healthy, gingivitis, and periodontitis participants, respectively. The average probing pocket depth and clinical attachment level were 4.263 and 5.962, respectively, in periodontitis patients.

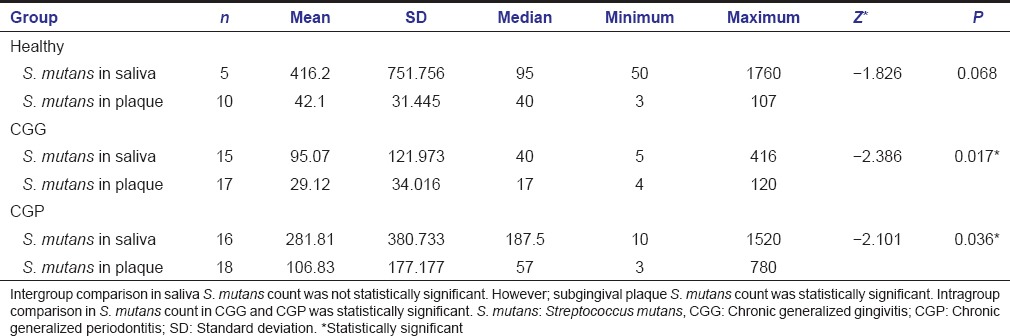

Inter- and intra-group comparison of Streptococcus mutans count in saliva and subgingival plaque samples

The highest colonies of S. mutans were seen in periodontitis patients (187.50) followed by healthy participants (95) and least seen in gingivitis patients (40). Similar to saliva samples, the highest colonies were seen in periodontitis cases (57) followed by healthy (40) and gingivitis cases (17). However, only the subgingival plaque samples showed statistical significance.

On intragroup comparison between plaque and saliva samples within each group, there was a statistical significant difference seen in gingivitis and periodontitis participants. More colonies of S. mutans were detected in saliva samples [Table 2].

Table 2.

Inter- and intra-group comparison of Streptococcus mutans count in all three groups

Comparison of mean saliva pH between the study groups

The mean saliva pH was 7.278, 7.273, and 7.001 in healthy, gingivitis, and periodontitis participants, respectively. However, the difference was not statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of mean saliva pH between the study groups

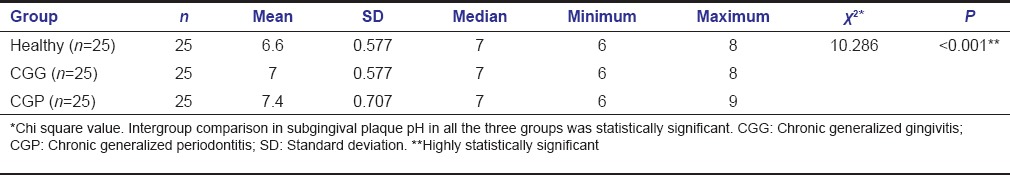

Comparison of mean subgingival plaque pH between the study groups

The mean subgingival plaque pH was 6.6, 7, and 7.40 in healthy, gingivitis, and periodontitis participants, respectively. Unlike the saliva samples, the plaque pH between the three groups showed statistical significance [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of mean subgingival plaque pH between the study groups

Correlation between Streptococcus mutans count and pH

When S. mutans count in saliva was correlated with saliva pH, only the healthy group showed a strong negative correlation between the two. On comparing the plaque pH with S. mutans count in plaque, both gingivitis and healthy groups had a strong positive correlation. All the other correlations were weak or negligible [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation between S. mutans count and pH

Comparison of periodontal parameters between all the three groups

The mean probing pocket depth in chronic periodontitis group was 4.263 mm and mean clinical attachment loss was approximately 5.962 mm. PI and GI between all three groups were statistically significant [Table 6].

Table 6.

Comparison of periodontal parameters between all the three groups

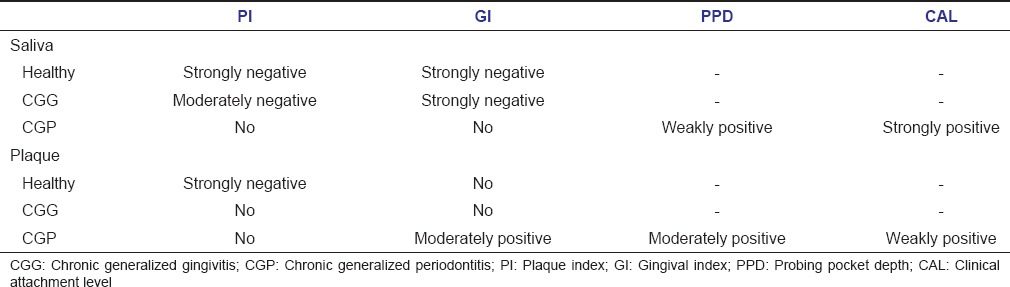

Correlation of Streptococcus mutans count with periodontal parameters

S. mutans in saliva elucidated a strong negative correlation in healthy group with gingival and PI and in gingivitis group with GI. However, periodontitis group showed a strong positive correlation with clinical attachment level [Table 7].

Table 7.

Correlation of Streptococcus mutans count with periodontal parameters

On correlating the count in plaque with periodontal parameters, only the healthy group demonstrated a strong negative correlation between S. mutans count and PI. All other parameters showed no correlation [Table 7].

Discussion

Dental caries and periodontitis are two of the most common oral diseases. They may be synergistically associated, negatively associated, or completely independent of each other. Positive association may relate to their microbiological etiology and biofilm formation. Furthermore, both diseases share many social and behavioral background factors in common, which have been related to their etiology.[16]

S. mutans is an aciduric Gram-positive coccus which may be naturally found in dental plaque and saliva. In this study, high proportions of S. mutans were seen in the saliva and subgingival plaque samples of chronic periodontitis. This is in contradiction to studies by Koll-Klais et al. who found high proportions of these species in healthy individuals, indicating that they help in maintaining a micro-ecological balance in the oral cavity.[17]

However, studies by Cortelli et al. found results that were in accordance to this study. The variation in the results could be attributed to difference in the sampling technique. According to Cortelli et al., unstimulated saliva is a representative of pooled subgingival area in advanced periodontitis patients. Most of the contradictory studies collected stimulated saliva.[18,19]

In this study, unstimulated saliva samples were collected. Furthermore, Preza et al. concluded from their study that S. mutans count appears directly co-associated with increased severity of periodontitis at older ages and in untreated patients. All patients in the periodontitis group fell in the older age group, untreated, and had severe attachment loss (≥5 mm).[5]

As with the saliva samples, subgingival plaque also showed more colonies of S. mutans in periodontitis group when compared to healthy and gingivitis groups. These results are in agreement with studies by Van der Reijden et al.[6]

It has been suggested that severe chronic periodontitis show low oxygen tension in deep pockets that favors the growth of microaerophilic species such as S. mutans. Reduced oxygen tension can also exclude them from some of the micro niches.[20]

Studies by Rickard et al. suggested that planktonic S. mutans demonstrate different gene expression than those present in the biofilm. The quorum sensing system of S. mutans in the biofilm may enable them to survive with obligatory anaerobes that are present in deeper periodontal pockets.[21]

Thus, in the oral biofilm, multiple species can co-aggregate to colonize the tooth surface or provide nutrients to other bacteria by metabolization of substrates. After cleaning the teeth, Streptococci mutans compete for colonizing saliva-coated enamel or dentin mediated by the expression of adhesion molecules or antibacterial molecules. Periodontitis-associated microorganisms can coexist with S. mutans and survive acidic conditions constrained by interspecies interactions. Thus, individuality of the host microflora could be responsible for disparity among studies pertaining to S. mutans colonization.[6]

When saliva pH was compared between all the three study groups, no statistical significance was seen. However, on comparing the subgingival plaque pH, there was a significant difference between the three groups. Studies by Cortelli et al. and Sah et al. found that the plaque pH was raised in periodontitis.[22]

In this study also, similar findings were observed. A possible explanation for this could be increased urea concentration in saliva which readily diffuses from saliva to subgingival environment, increased production of ammonia by obligatory anaerobes that are seen in abundance in periodontitis patients, and raised salivary calcium levels that have an affinity to be taken up by the biofilm. All these mechanisms are essential for the survival of obligatory anaerobes such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, which is considered as the key periodontal pathogen.[13]

When saliva pH and S. mutans count in saliva were correlated, it was found that only the healthy group showed a strong negative correlation. The other two groups showed weak or negligible correlation. Thus, as the saliva pH raises, acidogenic bacteria such as S. mutans fail to thrive.[23]

An interesting finding found in this study was that when subgingival plaque pH and S. mutans colonies in the plaque were correlated, both healthy and gingivitis groups showed a strong positive correlation. However, periodontitis patients demonstrated negligible correlation between the two.

Despite these correlations, none of them were statistically significant. Thus, based on these findings, it can be suggested that salivary pH may play a role in S. mutans colonization within the oral cavity. However, factors other than pH may be responsible for their survival subgingivally.[14,24]

On correlating the counts with periodontal parameters, both healthy and gingivitis groups showed either a negative or no correlation between S. mutans in saliva and plaque with GI and PI.

An important observation made in this study was that there was a strong positive correlation between S. mutans in saliva in periodontitis group and clinical attachment level. In most of the studies, the S. mutans count have positively correlated with clinical attachment level following periodontal therapy, suggesting their possible role in the development of root caries in periodontal maintenance patients.[6]

However, in this study, the count did correlate positively with clinical attachment level, but in untreated patients. The possible explanation for this could be that as the depth of the periodontal pocket increases, there is larger surface area for bacterial colonization. Thus, with increasing inflammation, there is ample amount of nutrients provided for further bacterial multiplication. Hence, an altered host response in periodontitis patients could play a role in bacterial colonization subgingivally.[25]

Conclusion

In this study, a higher colonization of S. mutans was seen in saliva and subgingival plaque samples of periodontitis patients. However, subgingival plaque pH did not play much role in their colonization. In addition, a positive correlation was seen between periodontal parameters and S. mutans count in chronic periodontitis. However, comparison of all results with other studies was not possible, as disparity between results exists.

Thus, it can be hypothesized from this study that more severe forms of periodontal disease may create different ecological niches for the proliferation of S. mutans. The mechanism by which their level increases with the severity of periodontitis needs to be determined. In addition, whether there is any association between periodontal disease progression and a higher proportion of S. mutans subgingivally needs further evaluation.

Hence, further studies are needed to elucidate whether they act synergistically with other putative periodontal pathogens or just merely present in the subgingival biofilm ecosystem.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vehkalahti M, Paunio I. Association between root caries occurrence and periodontal state. Caries Res. 1994;28:301–6. doi: 10.1159/000261990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fadel H, Al Hamdan K, Rhbeini Y, Heijl L, Birkhed D. Root caries and risk profiles using the Cariogram in different periodontal disease severity groups. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:118–24. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.538718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh PD, Bradshaw DJ. Physiological approaches to the control of oral biofilms. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:176–85. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110010901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravald N, Hamp SE, Birkhed D. Long-term evaluation of root surface caries in periodontally treated patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:758–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preza D, Olsen I, Aas JA, Willumsen T, Grinde B, Paster BJ. Bacterial profiles of root caries in elderly patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2015–21. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02411-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Reijden WA, Dellemijn-Kippuw N, Stijne-van Nes AM, de Soet JJ, van Winkelhoff AJ. Mutans streptococci in subgingival plaque of treated and untreated patients with periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:686–91. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028007686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loesche WJ, Syed SA, Schmidt E, Morrison EC. Bacterial profiles of subgingival plaques in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:447–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.8.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravald N, Birkhed D. Factors associated with active and inactive root caries in patients with periodontal disease. Caries Res. 1991;25:377–84. doi: 10.1159/000261395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiker J, van der Velden U, Barendregt DS, Loos BG. A cross-sectional study into the prevalence of root caries in periodontal maintenance patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:26–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nibali L, Pometti D, Tu YK, Donos N. Clinical and radiographic outcomes following non-surgical therapy of periodontal infrabony defects: A retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:50–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junior B, Debora Pallos D, Cortelli JR, Saraceni CH, Queiroz CS. Evaluation of organic and inorganic compounds in the saliva of patients with chronic periodontal disease. Rev Odontol Sci. 2010;25:234–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood LI, Al-Ezzy MY, Diajil AR. Correlation between Streptococci mutans and salivary IgA in relation to some oral parameters in saliva of children. J Bagh Coll Dent. 2014;26:71–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giongo FC, Mua B, Parolo CC, Carlén A, Maltz M. Effects of lactose-containing stevioside sweeteners on dental biofilm acidogenicity. Braz Oral Res. 2014;28 doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2014.vol28.0026. pii: S1806-83242014000100237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fadel HT, Al-Kindy KA, Mosalli M, Heijl L, Birkhed D. Caries risk and periodontitis in patients with coronary artery disease. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1295–303. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koll-Klais P, Mandar R, Leibur E, Mikelsaar M. Oral microbial ecology in chronic periodontitis and periodontal health. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2005;17:146–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortelli SC, Cortelli JR, Aquino DR, Holzhausen M, Franco GC, Costa Fde O, et al. Clinical status and detection of periodontopathogens and Streptococcus mutans in children with high levels of supragingival biofilm. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23:313–8. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motisuki C, Lima LM, Spolidorio DM, Santos-Pinto L. Influence of sample type and collection method on Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus spp. counts in the oral cavity. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:341–5. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Soete M, Dekeyser C, Pauwels M, Teughels W, van Steenberghe D, Quirynen M. Increase in cariogenic bacteria after initial periodontal therapy. J Dent Res. 2005;84:48–53. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rickard AH, Palmer RJ, Jr, Blehert DS, Campagna SR, Semmelhack MF, Egland PG, et al. Autoinducer 2: A concentration-dependent signal for mutualistic bacterial biofilm growth. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1446–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sah N, Pravin S, Bhutani H. Estimation and comparison of salivary calcium levels in healthy subjects and patients with gingivitis and periodontitis: A cross-sectional biochemical study. AOSR. 2012;2:13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darout IA. Oral bacterial interactions in periodontal health and disease. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2014;6:51–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwano Y, Sugano N, Matsumoto K, Nishihara R, Iizuka T, Yoshinuma N, et al. Salivary microbial levels in relation to periodontal status and caries development. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:165–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bratthall D, Serinirach R, Hamberg K, Widerström L. Immunoglobulin A reaction to oral streptococci in saliva of subjects with different combinations of caries and levels of mutans streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:212–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]