Abstract

Objective To determine what influences doctors' decisions about admission of patients to intensive care.

Design National questionnaire survey using eight clinical vignettes involving hypothetical patients.

Setting Switzerland.

Participants 402 Swiss doctors specialising in intensive care.

Main outcome measures Rating of factors influencing decisions on admission and response to eight hypothetical clinical scenarios.

Results Of 381 doctors agreeing to participate, 232 (61%) returned questionnaires. Most rated as important or very important the prognosis of the underlying disease (82%) and of the acute illness (81%) and the patients' wishes (71%). Few considered important the socioeconomic circumstances of the patient (2%), religious beliefs (3%), and emotional state (6%). In the vignettes, underlying disease (cancer versus non-cancerous disease) was not associated with admission to intensive care, but four other factors were: patients' wishes (odds ratio 3.0, 95% confidence interval 2.0 to 4.6), “upbeat” personality (2.9, 1.9 to 4.4), younger age (1.5, 1.1 to 2.2), and a greater number of beds available in intensive care (1.8, 1.2 to 2.5).

Conclusions Doctors' decisions to admit patients to intensive care are influenced by patients' wishes and ethically problematic non-medical factors such as a patient's personality or availability of beds. Patients with cancer are not discriminated against.

Introduction

In the United States and Canada intensive care accounts for 20% and 8% of inpatient hospital costs, respectively.1 Fair allocation of this scarce and expensive resource is the doctors' responsibility. Although guidelines have been developed to help doctors decide on who to admit to intensive care,2-4 they may be difficult to put into practice.5 In particular, the process by which doctors identify patients with a “reasonable prospect of substantial recovery” warranting intensive care is not well known.

Characteristics of patients that influence admission to intensive care are age, severity of illness, and reason for admission.5,6 Availability of beds has been inconsistently associated with triage decisions.6,7 Cognitive factors may also influence decisions, including biases in doctors' processing of information,8,9 the amount of information available,10 and the underlying disease.11 More specifically, and regardless of prognosis, patients with cancer may have more do not resuscitate orders and receive less cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and intensive care.12-16 The relative importance of these factors for decisions on admission to intensive care is not well known. We assessed what influences doctors' decisions to admit patients to intensive care. In particular we sought to determine if there was a bias against patients with cancer.

Methods

We carried out a survey of all members of the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine and of doctors who had taken the intensive care certification examination in the previous two years. An anonymous questionnaire, pretested for clarity of content, was sent out in November 2001 and then one and two months later. A prepaid envelope was included for its return.

The questionnaire

Doctors were asked to provide their personal characteristics and whether a relative or close acquaintance had ever been admitted to intensive care.

We assessed the importance of potential determinants of admission to intensive care in two ways. Firstly, respondents were asked to rate 19 factors using a five point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (very important). The factors were drawn from the literature and our own experience. Secondly, respondents were asked to decide on whether to admit to intensive care eight hypothetical patients who had been described in clinical vignettes.

Clinical vignettes

The vignettes described eight patients with medical problems admitted through the emergency department. Two scenarios were identical for all respondents. One was designed to elicit admission to intensive care (diabetic patient with myocardial infarction) and the other refusal to intensive care (acute respiratory failure warranting mechanical ventilation in a patient with relapsing leukaemia). In six vignettes potentially important features of the patient's situation or intensive care situation were manipulated. Each scenario tested three dichotomous factors combined in a factorial design resulting in eight versions of each scenario.

The influence of cancer was assessed in all six vignettes by comparing cancer with non-cancerous disease with a similar prognosis. Two scenarios tested the influence of the patient's age and wishes. Two vignettes evaluated the patient's personality and the number of intensive care beds available. One vignette assessed the patient's financial autonomy and another assessed the patient's social commitment. Family wishes were included in two scenarios, either as an explicit request or as a non-verbal attitude.

Rather than combine the eight versions of the six vignettes at random (48 permutations), we balanced the sets of scenarios in terms of risk factor profile. Thus each questionnaire included three vignettes with cancer and three with a non-cancerous underlying disease; if one scenario contained the combination of cancer, younger age, and one intensive care bed, another scenario presented the opposite combination of non-cancerous disease, older age, and three beds. Eight versions of the questionnaire were created, and each participant was randomly allocated to one of these.

Statistical analysis

We computed means and standard deviations for continuous variables and distributions for frequency of categorical variables. The rating of factors influencing triage was dichotomised (scores 4-5 v 1-3).

Clinical vignettes were analysed in two stages. Firstly, each scenario was analysed separately. We built a logistic regression model where the admission was the dependent variable and the three dichotomous factors the independent variables. Adjusted odds ratios for admission were obtained from these models. Secondly, we performed a pooled analysis for the factors tested in several vignettes. For factors appearing in two scenarios, such as age, we computed the McNemar matched odds ratios by cross tabulating decisions on admission for each matched pair of scenarios (for example, younger and older patient). The number of admissions for patients with cancer and non-cancerous disease (six scenarios) was compared for each respondent using a Wilcoxon matched pair test.

Results

Overall, 21 of 402 eligible doctors declined to participate because they no longer worked in intensive care. Of the remaining 381 doctors, 232 (61%) returned completed questionnaires. Response rates were similar across the eight versions of the questionnaire.

The mean age of respondents was 45.2 years (table 1). Most were men, worked at public hospitals, and were routinely involved in decisions on admissions to intensive care. Many had more than one certification in a medical specialty (n = 137; 59%), the most common being intensive care medicine and anaesthesiology. Most worked in surgical (n = 199; 86%) or medical intensive care (n = 159; 69%), and 15 (7%) worked in paediatric or neonatal intensive care. The mean number of beds in each intensive care unit was 11.4 (SD 6.4). Overall, 105 respondents (45%) reported that a relative or close acquaintance had ever been admitted to intensive care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 232 Swiss doctors who agreed to participate in questionnaire survey on determinants of admission of patients to intensive care. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Men | 193 (83) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 45.2 (7.1) |

| Mean (SD) years from graduation | 18.8 (7.3) |

| Mean (SD) years of practice in intensive care | 6.8 (6.5) |

| Medical specialty: | |

| Intensive care medicine | 132 (57) |

| Anaesthesiology | 139 (60) |

| Internal medicine | 67 (29) |

| Other | 53 (23) |

| Place of work: | |

| Regional public hospital | 112 (48) |

| University centre | 86 (37) |

| Private hospital | 25 (11) |

| Other | 9 (4) |

| Mean (SD) percentage of activity devoted to patient care | 52 (35) |

| Involved in decisions to admit to intensive care | 198 (85) |

Determinants of admission to intensive care

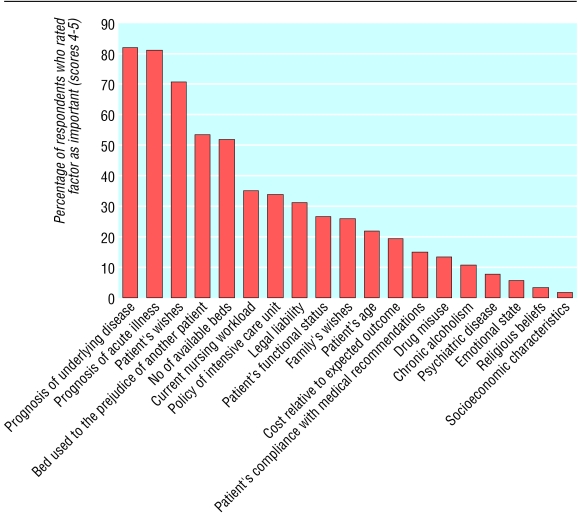

Among the factors influencing decisions on admission to intensive care, most doctors rated as important or very important the prognosis of the acute illness and of the underlying disease and the patients' wishes (figure). Half considered the number of available beds as important. Least influential were patients' religious beliefs, drug and alcohol misuse, psychiatric history, emotional state, and socioeconomic circumstances.

Figure 1.

Doctors' ranking of factors when assessing patients for admission to intensive care

Analysis of scenarios

One scenario (myocardial infarction) was designed so as to elicit an acceptance rate close to 100%; 217 respondents (94%) chose to admit the patient. In another scenario (respiratory failure in the presence of relapse with acute leukaemia) refusal was expected from most doctors; however 190 (82%) admitted the patient. Many (n = 105) added a comment, most often (n = 53; 50%) pointing out that they had hardly any choice as the patient was already mechanically ventilated.

Overall, 213 (92%) doctors answered the six remaining vignettes. The mean number of patients admitted to intensive care was 3.3 (SD 1.3) out of six. Three doctors (1%) admitted no one, 12 (6%) admitted one patient, 41 (19%) admitted two patients, 65 (31%) admitted three patients, 55 (26%) admitted four patients, 28 (13%) admitted five patients, and 9 (4%) admitted all six patients. Correlations between decisions on admission were weak (Spearman r - 0.15 to 0.21), indicating that there was no tendency for doctors to admit either all or none of the patients. The overall proportion of admissions across all variations of a given scenario ranged from 46% (fever, dysuria, and renal failure) to 66% (upper gastrointestinal bleeding).

In all the vignettes, admission rates varied significantly according to at least one experimentally manipulated factor (table 2). Having cancer as opposed to a non-cancerous disease did not influence the probability of admission in five scenarios. A patient with breast cancer presenting with haemolytic uraemic syndrome was, however, three times less likely to be admitted to intensive care than a patient with AIDS with the same condition. Respondents admitted a mean of 1.6 patients with cancer and 1.7 patients with non-cancerous disease (P = 0.68).

Table 2.

Influence of factors assessed in hypothetical scenarios on probability of being admitted to intensive care

| Scenario and factors | No responding | No (%) admitted to intensive care | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shortness of breath in patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

| ||||

| Underlying disease: | ||||

| Heart failure

|

122

|

77 (63)

|

0.87 | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9)

|

| Colon cancer | 108 | 67 (62) | 1.0 | |

| Age: | ||||

| 57 years

|

117

|

78 (67)

|

0.20 | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.6)

|

| 80 years | 112 | 66 (59) | 1.0 | |

| Patient's wishes: | ||||

| Do everything you can

|

122

|

89 (73)

|

0.001 | 2.7 (1.5 to 4.6)

|

| No aggressive care | 107 | 55 (51) | 1.0 | |

|

Fever and dysuria in elderly patient with urethral obstruction

| ||||

| Underlying disease: | ||||

| Benign hyperplasia

|

117

|

50 (43)

|

0.27 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2)

|

| Prostate cancer | 112 | 56 (50) | 1.0 | |

| Personality trait: | ||||

| Upbeat, sociable

|

122

|

70 (57)

|

<0.001 | 2.7 (1.6 to 4.7)

|

| Sad, withdrawn | 107 | 36 (34) | 1.0 | |

| No of intensive care beds available: | ||||

| 3

|

115

|

62 (54)

|

0.02 | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.3)

|

| 1 | 114 | 44 (39) | 1.0 | |

|

Fatigue and petechiae in 42 year old woman

| ||||

| Underlying disease: | ||||

| AIDS

|

116

|

72 (62)

|

<0.001 | 3.0 (1.7 to 5.2)

|

| Breast cancer | 110 | 41 (37) | 1.0 | |

| Source of income: | ||||

| Work

|

107

|

53 (50)

|

0.89 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7)

|

| Social security | 119 | 60 (50) | 1.0 | |

| Family's wishes: | ||||

| Do everything you can

|

120

|

72 (60)

|

0.001 | 2.6 (1.5 to 4.6)

|

| No aggressive care | 106 | 41 (39) | 1.0 | |

|

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patient with gastric ulcer

| ||||

| Underlying disease: | ||||

| Liver cirrhosis

|

108

|

69 (64)

|

0.51 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.5)

|

| Lung cancer | 122 | 83 (68) | 1.0 | |

| Age: | ||||

| 49 years

|

112

|

82 (73)

|

0.026 | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.8)

|

| 73 years | 118 | 70 (59) | 1.0 | |

| Patient's wishes: | ||||

| Do everything you can

|

109

|

89 (82)

|

<0.001 | 4.3 (2.3 to 7.9)

|

| No aggressive care | 121 | 63 (52) | 1.0 | |

|

Shortness of breath and malaise in 46 year old woman

| ||||

| Underlying disease: | ||||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus

|

112

|

62 (55)

|

0.32 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1)

|

| Ovarian cancer | 117 | 57 (49) | 1.0 | |

| Personality trait: | ||||

| Strong, courageous

|

107

|

73 (68)

|

<0.001 | 3.5 (2.0 to 6.2)

|

| Anxious, discouraged | 122 | 46 (38) | 1.0 | |

| No of intensive care beds available: | ||||

| 3

|

114

|

67 (59)

|

0.04 | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.0)

|

| 1 | 115 | 52 (45) | 1.0 | |

|

Nausea and vomiting in elderly patient with hypercalcaemia

| ||||

| Underlying disease: | ||||

| Hyperparathyroidism

|

109

|

56 (51)

|

0.45 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4)

|

| Multiple myeloma | 117 | 66 (56) | 1.0 | |

| Social commitment: | ||||

| Socially active

|

119

|

73 (61)

|

0.02 | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.2)

|

| Isolated, withdrawn | 107 | 49 (46) | 1.0 | |

| Family's attitude: | ||||

| Involved, present

|

107

|

59 (55)

|

0.74 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8)

|

| Unconcerned, about to leave | 119 | 63 (53) | 1.0 | |

The patient's wish to receive maximal treatment was associated with an increased odds of admission, as were certain personality traits. Patients described as upbeat and sociable or strong and courageous were more likely to be admitted than patients described as sad and withdrawn or anxious and discouraged. The patient's means of living did not affect the probability of admission, but social involvement did. Younger age was associated with a slightly higher admission rate in the two scenarios where this factor was assessed. Availability of three intensive care beds was related to a higher probability of a patient being admitted. A difference was found in the way the family's attitude was considered. An explicit request increased the chances of admission whereas a non-verbal emotional attachment did not.

Matched analyses confirmed that patients' wishes, personality traits, age, and availability of intensive care beds were significantly associated with the probability of admission (table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of matched pairs of scenarios

|

Hypothesised probability of admission to intensive care

|

Actual admission to intensive care

|

McNemar odds ratio (95% CI)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | High | Low | Both | Neither | High only | Low only | P value | |

| Age | Younger | Older | 89 | 23 | 71 | 46 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.2) | 0.026 |

| Patient's wish | Do everything | No aggressive care | 89 | 23 | 88 | 29 | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.6) | <0.001 |

| Personality trait | Upbeat, courageous | Sad, discouraged | 51 | 55 | 90 | 31 | 2.9 (1.9 to 4.4) | <0.001 |

| Availability of intensive care beds | Three | One | 51 | 55 | 77 | 44 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.5) | 0.003 |

Discussion

Specific factors influence doctors' decisions to admit patients to intensive care. Some factors, such as consideration for the patient's wishes, are desirable and agree with current recommendations. Others, for example availability of beds or a patient's personality, are ethically questionable. Moreover, we found a discrepancy between the acknowledged importance given to some factors and the importance as shown by the hypothetical clinical scenarios, suggesting that unconscious processes may be at work and lead to biased decisions.

An important finding was the absence of discrimination against patients with cancer. Medical progress in the treatment of cancer and its complications gives the hope of improved survival and better quality of life. Thus doctors' perception of the therapeutic options for malignancies may be changing. The fact that the patient with AIDS presenting with haemolytic uraemic syndrome was more often admitted to intensive care than the patient with breast cancer does not necessarily imply discrimination. Haemolytic uraemic syndrome is a rare occurrence in patients with HIV infection and has a grave prognosis. The doctors in our study may have thought that HIV infection was more amenable to treatment than advanced breast cancer. Insufficient knowledge rather than bias would account for the difference in admission rates between the two patients.

Doctors rated the potential determinants of decisions for admission in a way that was generally consistent with published guidelines. In particular, most considered of paramount importance the prognosis of the acute illness and of the underlying disease. These two factors belong to the basic principles guiding triage, and earlier studies have shown that they are associated with admission to intensive care.5-7

Patients' wishes were considered important by most respondents, and in the experimental part of the study were strongly related to the decision to admit. This reflects a departure from the traditional paternalistic attitude and the increasing attention paid to self determination and autonomy.17

This sharply contrasts with the finding that the patient's personality equally influenced doctors' decisions. The preference to admit patients with a positive attitude was not conscious as respondents rated the patient's emotional state low among the determinants for admission, which agrees with recommendations that a patient's personal and behavioural characteristics should not influence triage.3 Similarly, a patient described as socially active was more likely to be admitted. These results raise ethical concerns.2,3 Doctors seemed to assign a certain worth to the patient based on subjective and mainly unconscious criteria. Unfair allocation of resources may result. This attitude can reflect both individual and broader western cultural values.18

Availability of beds was considered important by the respondents and was correlated with the decision to admit in the vignettes. Previous studies have suggested that fewer patients are admitted when beds are scarce.6 Our study shows that this is the case. Doctors also recognised different aspects of rationing such as nursing workload and the optimal use of available beds.19

Age was moderately associated with admission to intensive care. Age is in itself probably not an important determinant and is balanced against medical and contextual factors.9

Doctors' decisions varied according to the family's wishes and attitudes. An explicit request was related to the decision to admit to intensive care but apparent emotional attachment was not. This raises the issues of whether the patient's best interests were the doctor's prime concern in both situations and whether the doctor should actively seek the preferences of the family. Decision making in the presence of an incompetent patient is problematic. The accuracy of proxy judgments is generally poor,20 but doctors' predictions of the patient's preferences are even worse.21 Family members can also exert undue pressure on the doctor,22 and they often fail to fully understand their relative's state of health and related issues.23

The main limitation of our study is the possible discrepancy between doctors' decisions in practice and their answers to vignettes with hypothetical patients. However, the validity of the decisions is supported by the overall admission rate of about 50% and the respondents' straightforward answers, as exemplified by the consideration given to the availability of beds. The high admission rate of the patient with relapsing leukaemia may seem surprising, but the respondents' comments about having little choice because the patient was mechanically ventilated, further indicate that their answers were based on their everyday practice. A previous study found no correlation between relapsing leukaemia with severe acute respiratory failure and admission to intensive care.5 The response rate of 61% raises the possibility of non-response bias, particularly for descriptive variables such as the rating of factors influencing decisions on admission. Because response rates were similar for the eight versions of the questionnaire, a bias is unlikely in measures of association between the experimentally manipulated factors and the reported decisions to admit patients.

What is already known on this topic

Biases and practical constraints may influence doctors' decisions on admitting patients to intensive care

The relative importance of these factors is not well known

What this study adds

Patients' wishes and ethically questionable factors such as a patient's personality or availability of beds influence doctors' decisions on admission to intensive care

Unconscious value judgments may lead to an unfair allocation of intensive care beds

In conclusion, doctors do not discriminate against patients with cancer when deciding on admission to intensive care. The decision making process is influenced by the patient's wishes and ethically problematic non-medical factors such as the patient's personality or availability of beds. The medical community must be aware of the existence of unconscious value judgments leading to possible biased decisions for admissions to intensive care.

Contributors: J-CC proposed the original idea, which was developed by all authors. ME ran the study and entered the data. TVP analysed the results. All authors contributed to writing the paper and will act as guarantors.

Funding: Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Clinical ethics committee of the Geneva University Hospitals.

References

- 1.Jacobs P, Noseworthy TW. National estimates of intensive care utilization and costs: Canada and the United States. Crit Care Med 1990;18: 1282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Society of Critical Medicine Ethics Committee. Consensus statement on the triage of critically ill patients. JAMA 1994;271: 1200-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Thoracic Society. Fair allocation of intensive care unit resources. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156: 1282-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society of Critical Medicine. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Crit Care Med 1999;27: 633-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Vinsonneau C, Garrouste M, Cohen Y, et al. Compliance with triage to intensive care recommendations. Crit Care Med 2001;29: 2132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprung CL, Eidelman LA. Triage decisions for intensive care in terminally ill patients. Intensive Care Med 1997;23: 1011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joynt G, Gomersall C, Tan P, Lee A, Cheng C, Wang N. Prospective evaluation of patients refused admission to an intensive care unit: triage, futility and outcome. Intensive Care Med 2001;27: 1459-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg J. Sociologic influences on decision-making by clinicians. Ann Intern Med 1979;90: 957-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redelmeier D, Ferris L, Tu J, Hux J, Schull M. Problems for clinical judgement: introducing cognitive psychology as one more basic science. Can Med Assoc J 2001;164: 358-60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuckton T, List N. Age as a factor in critical care unit admission. Arch Intern Med 1995;155: 1087-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghusn HF, Teasdale TA, Boyer K. Characteristics of patients receiving or foregoing resuscitation at the time of cardiopulmonary arrest. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45: 1118-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence V, Clark G. Cancer and resuscitation. Does the diagnosis affect the decision? Arch Intern Med 1987;147: 1637-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanson L, Danis M, Garrett J, Mutran E. Who decides? Physicians' willingness to use life-sustaining treatment. Arch Intern Med 1996;156: 785-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachter R, Luce J, Hearst N, Lo B. Decisions about resuscitation: inequities among patients with different diseases but similar prognoses. Ann Intern Med 1989;111: 525-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanvetyanon T, Leighton J. Life-sustaining treatments in patients who died of chronic congestive heart failure compared with metastatic cancer. Crit Care Med 2003;31: 60-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claessens MT, Lynn J, Zhong Z, Desbiens NA, Phillips RS, Wu AW, et al. Dying with lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from SUPPORT study (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments). J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48: S146-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincent JL. Information in the ICU: are we being honest with our patient? The results of a European questionnaire. Intensive Care Med 1998;24: 1251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furnham A, Simmons K, McClelland A. Decisions concerning the allocation of scarce medical resources. J Soc Behav Pers 2000;15: 185-200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarnow-Mordi WO, Hau C, Warden A, Shearer AJ. Hospital mortality in relation to staff workload: a 4-year study in an adult intensive care unit. Lancet 2000;356: 185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suhl J, Simons P, Reedy T, Garrick T. Myth of substituted judgment. Surrogate decision making regarding life support is unreliable. Arch Intern Med 1994;154: 90-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coppola KM, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD. Accuracy of primary care and hospital-based physicians' predictions of elderly outpatients' treatment preferences with and without advance directives. Arch Intern Med 2001;161: 431-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ely JW, Peters PG Jr, Zweig S, Elder N, Schneider FD. The physician's decision to use tube feedings: the role of the family, the living will, and the Cruzan decision. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40: 471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med 2000;28: 3044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]