Abstract

Nephrology has conducted few high–quality clinical trials, and the trials that have been conducted have not resulted in the approval of new treatments for primary or inflammatory glomerular diseases. There are overarching process issues that affect the conduct of all clinical trials, but there are also some specialty–specific issues. Within nephrology, primary glomerular diseases are rare, making adequate recruitment for meaningful trials difficult. Nephrologists need better ways, beyond histopathology, to phenotype patients with glomerular diseases and stratify the risk for progression to ESRD. Rigorous trial design is needed for the testing of new therapies, where most patients with glomerular diseases are offered the opportunity to enroll in a clinical trial if standard therapies have failed or are lacking. Training programs to develop a core group of kidney specialists with expertise in the design and implementation of clinical trials are also needed. Registries of patients with glomerular disease and observational studies can aid in the ability to determine realistic estimates of disease prevalence and inform trial design through a better understanding of the natural history of disease. Some proposed changes to the Common Rule, the federal regulations governing the ethical conduct of research involving humans, and the emerging use of electronic health records may facilitate the efficiency of initiating multicenter clinical trials. Collaborations among academia, government scientific and regulatory agencies, industry, foundations, and patient advocacy groups can accelerate therapeutic development for these complex diseases.

Keywords: clinical trial, glomerular disease, registries, Cooperative Behavior, Electronic Health Records, Foundations, Government, Humans, kidney, Kidney Failure, Chronic, Kidney Glomerulus, nephrology, Patient Advocacy, Phenotype, Prevalence, Registries, Research, Science, Specialization

Introduction

It has been a little over a decade since Strippoli et al. (1) pointed out that nephrology was at the bottom of the list of medical subspecialties with regard to the conduct of clinical trials in both quantity and quality. The authors of the accompanying editorial felt that perhaps the problem was overstated but concurred that there was a need for improvement (2). More recently, a review of ClinicalTrials.gov seemed to show some improvement, although the overall percentage of nephrology interventional studies remained low at 2.6% of the trials reviewed, about one half that of cardiology (3). This paucity of high-quality data, primarily randomized, controlled trials (RCTs), to evaluate new therapies in kidney diseases remains a concern (4,5), and among the various subcategories of nephrology research, primary glomerular disease represents a comparatively small percentage of the group (1,2). Additionally, it is particularly striking to note that, since the 1962 Drug Efficacy Amendments, which required that new drugs be shown to be effective as well as safe to be approved in the United States, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved no drug for the treatment of a primary or inflammatory glomerular disease. Recently, belimumab and rituximab were approved by the FDA for the treatment of SLE, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis, respectively, but were not specifically approved for the associated GN. So what issues underlie the difficulties of conducting, and successfully completing clinical trials in nephrology? Some process issues are certainly not unique to nephrology—slow institutional review board (IRB) approval, slow contract/subcontract ratification, and recruitment shortfalls often caused by an overestimation of available participants (6) as well the need for more training in clinical trial design and implementation. However, some issues are more specific to nephrology. One issue could simply be labeled culture—nephrologists’ uncertainty that there is truly equipoise between different treatment options, resulting in an unwillingness to relinquish control of their patients to a randomized study, even for a short time (1,6). Another is the need for accurate disease phenotyping and risk classification. The clinical classification of many glomerular diseases (noninflammatory and inflammatory) is inadequate, relying primarily on histopathology rather than an understanding of the molecular underpinnings of these diseases. Histopathology alone does not adequately predict the heterogeneous natural history or response to therapy for individuals within a given glomerular disease category. There are difficulties in identifying appropriate druggable targets and clinically useful biomarkers that could serve as indicators of disease activity or surrogate end points in primary glomerular disease (7–9). One promising target for the treatment of membranous nephropathy (MN) is the phospholipase A2 receptor, and circulating levels may also be a marker of disease activity (10). Hopefully, we will be able to identify similar potential targets for other forms of primary glomerular disease. The inflammatory glomerulonephritides have a relatively longstanding history of defined biomarkers associated with disease diagnosis and activity—anti-double stranded DNA, anti-C1q, and complement levels in lupus nephritis, and ANCAs for pauci-immune/ANCA-associated vasculitis—which has contributed to strong trial design. More recently, serum thiols and anti-C3b IgG have been proposed for lupus nephritis (11,12), and urinary soluble CD163 has been proposed for ANCA-associated vasculitis (13).

There are now registries of patients with glomerular disease in place that may alleviate some recruitment challenges. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) has invested in several observational studies that should help to inform clinical trial design. The FDA and the American Society of Nephrology have partnered to establish the Kidney Health Initiative (KHI). The KHI objectives include fostering the development of therapies for diseases that affect the kidney by facilitating collaborations among patient groups, nephrologists and other health professionals, industry, and government (https://www.asn-online.org/khi/). The Critical Path Institute, an independent, nonprofit organization, was created to increase collaboration among scientists within the FDA, academia, and industry to improve the drug development and regulatory process for medical products. Some ways in which these organizations, basic scientists, and clinical trialists can all engage to move the field forward will be discussed in this paper.

National Institutes of Health Investments, Requirements, and Limitations

The NIDDK at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds much of the glomerular disease research in the United States. Although 60%–70% of the funding is for basic research, there have been significant investments in glomerular disease clinical consortia. In 2008, a multicenter, prospective, open label, RCT in FSGS (the FSGS-Clinical Trial) was completed in children and young adults to determine if treatment with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in conjunction with oral pulse corticosteroids is superior to treatment with cyclosporin A in inducing remission of proteinuria over 12 months. The findings have been published, but the conduct of the trial reflected many of the challenges referenced above, including slow IRB approval, slow subcontract ratification, and recruitment shortfalls (14,15).

Currently, there are two longitudinal, observational glomerular disease cohorts that are recruiting patients: the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) and Cure Glomerulonephropathy (CureGN) studies. NEPTUNE is in its sixth year and focuses on three glomerular diseases associated with the nephrotic syndrome: minimal change disease (MCD), FSGS, and MN. Participants are enrolled before their first clinically indicated biopsy, and when the biopsy is performed, a research core is obtained for genomic analysis. Using systems biology, NEPTUNE is analyzing tissue, serum, urine, and phenotypic and genomic data in approximately 500 children and adults. CureGN, however, is projected to recruit 2400 patients, 600 in each of four disease categories: MCD, FSGS, MN, and IgA nephropathy. The plan is to recruit equal numbers of prevalent (defined as having a renal biopsy obtained within 5 years of disease) and incident (defined as having a biopsy <6 months before enrollment) patients.

There are other large NIH–funded consortia that include significant numbers of participants with glomerular disease, although glomerular disease is not their specific focus. These include the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort, the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Study, and the Human Heredity and Health in Africa Kidney Disease Research Network (16).

Although these clinical research investments are significant, there are requirements and limitations inherent in the NIDDK funding of large consortia. The entire process from initial concept to funding of a consortium can take 2–2.5 years and is very dependent on available or projected funds. The first step in the creation of a consortium is the drafting, refining, and thorough discussion by the NIDDK staff of an initiative concept, which must subsequently be approved by the NIDDK External Advisory Council to go forward. An open meeting with invited speakers is usually planned to discuss the initiative and get a sense of the state of the science to appropriately develop the basis for a request for applications. An example of such a meeting occurred before the initiation of CureGN (http://www.niddk.nih.gov/news/events-calendar/Pages/glomerular-disease-pathophysiology-biomarkers-and-registries-for-facilitating-translational-research.aspx#tab-event-details). If funding is approved for the project, a request for applications is issued. Proposals are received, evaluated, and ultimately approved by the Advisory Council for funding. In contrast, investigator-initiated projects (R01s) can move forward more quickly but are often limited in size and scope because of budget restrictions. In some instances, to facilitate feasibility and help with budgetary constraints, the NIH partners with industry or advocacy groups for provision of pharmaceuticals and/or financial support.

Partnering with Industry

Given the expense and complexity in design and execution of RCTs, more nimble approaches are needed to identify molecular targets with promise, especially those that could be amenable to intervention with drugs repurposed from other uses. Partnering with industry early in the translation of bench discoveries into the clinic would facilitate proof of concept human studies and the conduct of adaptive clinical trials (17). In adaptive trials, prespecified changes in design or analyses are guided by examination of the accumulated data at an interim point in the trial. Such designs can improve trial efficiency, make trials more informative, and increase the likelihood of detecting a treatment effect (if such an effect exists) (18). Ultimately, cooperation with industry partners should accelerate trial implementation and improve the care of patients. However, barriers to establishing industry partnerships must be addressed. Change is needed by both our community and industry colleagues to improve our record in clinical trials completion.

Recently, the pharmaceutical industry has recognized opportunities for drug development for glomerular disease. However, budgets often fail to adequately recognize the effort needed to identify patients with glomerular disease who meet eligibility criteria for trials. These participants have rare diseases, and eligibility criteria often require time-consuming interactions outside of the home institution. Although clinical trials are most often driven by industry, trial designs are often improved with early input from basic and clinical scientists, clinicians, and patients. An alternate model, in which an academic investigator serves as the sponsor of a study that is funded by industry, may also be an important means to advance drug development in this area. Industry should also codify and post mechanisms for investigators to propose novel targets and clinical trials; currently, identification of the correct industry contact can be difficult. Early interactions with the FDA can also significantly improve trial design and the likelihood that the trials will be sufficiently rigorous in design and execution to meet FDA requirements for drug registration. Unfortunately, interactions between academic investigators, their universities, and industry partners often bog down over intellectual property ownership. These protracted negotiations need reform, particularly at early stages when the goal is to establish data suggesting efficacy of a drug in patients.

There are recent developments that promote interactions between academic centers, practice groups, patients, industry, and the government. The goal of the KHI is to foster new therapies for kidney diseases by creating a collaborative, precompetitive space for interactions between industry, government, patients, scientists, and the kidney care community. NephCure Kidney International created the NephCure Accelerating Cures Institute to reduce obstacles to successful implementation of glomerular disease trials by creating a national network of clinical trial sites in research hospitals and community clinics with established infrastructure, facilitating interactions with industry partners with novel glomerular disease treatments, and engaging the patient community to reduce the drug development timeline from 15 to 5 years (http://nephcure.org/research/naci/).

Regulatory Considerations

End Points

In early phases of drug development, pharmacodynamic or response biomarkers are used to show that a biologic response has occurred in an individual who has received an intervention or exposure. Treatment effects on such biomarkers are used to support proof of concept and guide dose selection for later clinical trials. Given their important role in drug development, more attention should be given to identifying pharmacodynamic biomarkers, beyond proteinuria, that can be used in clinical trials in primary glomerular disease. Phospholipase A2 receptor is a good example for MN. In later phases of drug development, the goal is to establish that a drug is safe and effective for its intended use. ESRD is an important clinical outcome, but it is a late event in many glomerular diseases, making it potentially difficult to show an effect on ESRD over the course of a feasible clinical trial. Accordingly, there has been significant interest in the use of surrogate end points in clinical trials of glomerular diseases.

A surrogate end point is a biomarker used in therapeutic trials as a substitute for a clinically meaningful end point. Surrogate end points offer important advantages, because they can enable faster and cheaper drug development. They may be viewed as the only viable option in some settings, particularly when a therapy is being developed to treat early stages of a slowly progressive disease. However, disease processes are often complex, and drugs can have unintended effects, making identification of biomarkers that can reliably predict a treatment’s effect on clinical outcomes very challenging.

In trials of CKD, a doubling of serum creatinine and lesser declines in renal function have been accepted as surrogate end points of treatment effects on progression to ESRD. Although there has been significant interest in proteinuria reduction as a surrogate end point, the FDA has not broadly accepted this as a basis for approval of therapies being developed to treat kidney diseases but has focused on data supporting the use of proteinuria reduction as a surrogate end point within the context of specific glomerular diseases. One recently completed collaborative effort evaluated the data supporting complete and partial remission of proteinuria as surrogate end points for a treatment effect on progression to ESRD in patients with primary MN at high risk of progression. A new project, sponsored by the KHI, plans to evaluate the data supporting proteinuria reduction and other biomarkers as surrogate end points for registration trials in IgA nephropathy. Another KHI project in collaboration with the Lupus Nephritis Trial Network will examine the strengths and weaknesses of existing surrogate end points and make data-driven recommendations about biomarker outcome measures and surrogate end points for lupus nephritis trials.

Although surrogate end points provide an important means to establish the efficacy of therapies, it is important not to lose sight of other end points that can be used to support medical product approval. In recent years, there has been increasing recognition of the importance of the patient voice in drug development, particularly the use of patient–reported outcome (PRO) measures as end points. Available data indicate that patients with primary glomerular disease have significant impairments that can be detected with generic PRO measures; however, disease-specific instruments may be needed to adequately capture the distinctive features of glomerular disease and how these affect the patient experience. PRO issues are discussed more extensively in another paper in this series.

Pediatric Issues

Historically, the majority of drugs used in pediatric practice were used off label, because most drug development programs did not include children. Medications were often administered to children empirically, assuming that they were “little adults.” This resulted in pediatric dosing recommendations derived solely as fractions of adult dosing. Safety and efficacy were assumed to be the same in children and adults, not taking into account known or potential safety and efficacy differences in a growing and developing pediatric patient. Before the passage of important pediatric legislation, many pharmaceutical manufacturers were reluctant to study drugs in children because of ethical, financial, or trial design challenges (19). Under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA), first passed by Congress in 2002, the FDA may grant 6 months of marketing exclusivity to sponsors who complete the voluntary pediatric studies that the FDA determines are of public health benefit (20). The Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), first enacted in 2003, gives the FDA authority to require pediatric assessments of new drugs for all new active ingredients, indications, dosage forms, dosing regimens, and routes of administration. The pediatric assessment must include data adequate to assess the dosing, safety, and effectiveness of the product for the claimed indications in all relevant pediatric subpopulations (21).

Importantly, the BPCA and the PREA do not provide for a different evidentiary standard for the demonstration of effectiveness and safety for products intended for use in children. However, the feasibility of adequate and well controlled clinical efficacy trials may be hindered because of limited availability of pediatric patients. Moreover, there are additional safeguards that must be considered when conducting research in pediatric patients (22). In 1994, the FDA finalized a set of rules for the extrapolation of efficacy to the pediatric population from adequate, well controlled studies with adults. Such extrapolation depends on a series of evidence-based assumptions—the disease progression and responses to intervention are similar in the adult and pediatric populations, and the two populations have similar exposure-response relationships (23). The FDA examines several factors before making assumptions of similarity, including disease pathogenesis, criteria for disease definition, clinical classification, measures of disease progression, and pathophysiologic, histopathologic, and pathobiologic characteristics. Support for these assumptions may be derived from sponsor data, published literature findings, expert panel, workshop or consensus documents, or previous experience with other products in the same class. Importantly, safety profiles may differ between adult and pediatric populations; therefore, safety information cannot be extrapolated from trials in adults (24). In the case of glomerular diseases that affect both adults and children, development of evidence that could support the use of pediatric extrapolation may increase the efficiency and feasibility of product development. In addition, under certain circumstances (e.g., for rare, life–threatening diseases or for studies in which sufficient safety data in children already exist), clinical investigations may include both children and adults in the same trial. For example, a controlled trial evaluating sparsentan in the treatment of both pediatric and adult FSGS (the Randomized, Double-Blind, Safety and Efficacy Study of RE-021 [Sparsentan] in FSGS [DUET]) was initiated in 2012.

The Case for Registries

Registries can take different formats depending on the intended use of the registry data. Investigators around the world have initiated a variety of observational studies of patients with glomerular disease during the past decade. These studies have used a spectrum of methodologic approaches from simple cross–sectional contact registries of self-reported diagnosis to single–center longitudinal observation registries of clinical phenotype to national observational studies using linked electronic health records (EHRs) to international multicenter consortia of basic, translational, and clinical scientists conducting detailed long–term longitudinal observational studies (Table 1). The emerging use of EHRs both nationally and internationally offers unique opportunities to facilitate harmonized clinical research endeavors. The exchange of standardized health information, customized for clinical studies while assuring confidentiality, will enable investigators to expand cohorts for collaboration and sharing of information regarding trials, registries, and biorepositories (25).

Table 1.

Current glomerular disease clinical consortia and registries

| Consortium Namea | Type of Study | Biosampling | Funding Sources | Still Enrolling | Clinical Phenotypes |

| United States | |||||

| CureGN | Observational | Yes | NIDDK | Yes | Biopsy-proven MCD, FSGS, MN, IgAN |

| NEPTUNE | Observational | Yes | NIDDK and NCATS | Yes | NS with biopsy-proven MCD, FSGS, MN |

| UNC Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network | Registry | Yes | NIDDK P01 and Philanthropy | Yes | All glomerular diseases |

| NephCure Accelerating Cures Institute | Registry | No | NephCure Kidney International | Yes | All forms of NS |

| Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Study | Observational | Yes | NIDDK | No | All causes of CKD in children |

| Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort | Observational | Yes | NIDDK | No | All causes of CKD in adults |

| North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies Group | Registry | No | Industry | Yes | All causes of CKD in children |

| International | |||||

| Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry | Registry | No | Divisional Fund University Health Network | Yes | All biopsy–proven forms of GN |

| British Columbia Glomerulonephritis Network and Registry | Registry | No | BC Provincial Renal Agency | Yes | Biopsy-proven GN |

| PodoNet (Europe only) | Observational | Yes | EU via EURenOMICS Project | Yes | Steroid-resistant NS |

| NephroS—part of the United Kingdom Renal Rare Disease Registry | Observational | Yes | National Institute for Health Research; Kidney Research UK; Kids Kidney Research; industry partnerships | Yes | Idiopathic NS in children and adults |

| EURenOMICS | Observational | Yes | European community—International Rare Disease Research Consortium | Yes | SRNS, MN, tubulopathies, complement disorders, congenital kidney malformations |

| China-DiKip | Observational | Yes | National funding | Yes | Glomerular disease |

| Human Heredity and Health in Africa Kidney Disease Research Network | Observational | Yes | NIH (common fund, NHGRI, NIDDK) | Yes | All causes of CKD in adults and children |

CureGN, Cure Glomerulonephropathy; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; MCD, minimal change disease; MN, membranous nephropathy; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; NEPTUNE, Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network; NCATS, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NS, nephrotic syndrome; UNC, University of North Carolina; BC, British Columbia; EU, European Union; SRNS, steroid responsive nephrotic syndrome; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NHGRI, National Human Genome Research Institute.

Consortia websites have information on entry criteria and available data.

There can be a significant cost to setting up a patient registry, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule mandates the way in which protected health information is used or shared. Therefore, each individual may be assigned a unique reference code with all personally identifiable information removed, or patients may consent to participate in studies that include personally identifiable information. These registries should have appropriate methods to protect privacy and data security as well as appropriate ethics board approval. There are multiple ways to capture data, which can also affect cost—paper forms and electronic application–based forms as well as web-based forms.

There are many ways in which registries can be valuable tools for enhancing potential trial success, not the least of which is assessing the size of the potential study population to allow for more realistic estimates of target recruitment numbers (Table 2). However, with multiple registries for glomerular diseases, there is concern about redundancy, competing interests, and dividing patients and resources as well as participant confusion and fatigue because of participation in multiple registries. One consideration may be the establishment of global registries for glomerular diseases. There are a few global registries fairly early in development that may serve as examples for such an effort for glomerular diseases. One is the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Global Rare Diseases Patient Registry Data Repository Program, which integrates coded data from numerous national and international patient registries for rare diseases. Investigators representing glomerular disease registry programs in several countries are working to harmonize protocols and approaches in an informal International Nephrotic Syndrome Network. This loose network includes >9500 patients from 12 national networks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and China. Of course, these global efforts require consensus on many levels—identification of topics for joint/comparative studies, consensus on end point definitions, common data elements and terminology, support for compatibility and interoperability, and a global unique identifier assigned to each patient for tracking.

Table 2.

Potential value of disease registries and cohorts

| (1) Defining the disease to be studied |

| Determining disease prevalence: size of the potential study population and how this cohort changes as one alters enrolment criteria |

| Natural/clinical history: disease characteristics, including how biomarkers perform over time |

| (2) Defining meaningful therapeutic end points and/or surrogate end points for a particular disease cohort |

| (3) Identifying and evaluating human therapeutic targets |

| (4) Defining biomarkers that may be relevant to the full disease cohort or a disease subgroup |

| (5) Improving access for patient recruitment and enhancing patient retention |

| (6) Comparisons of global treatment modalities and patient survival rates |

| (7) Achieving critical patient mass to reach sufficient power for multiple comparisons (efficacy/safety) |

| (8) Valid adjustments in multivariate analyses (age and ethnicity) |

Are We Ready to Conduct High-Quality Trials?

Given our inadequate understanding of the biology and our archaic classification system for glomerular disorders, it is not surprising that our therapeutic approach to these diseases is imperfect; current therapies lack a clear biologic basis, are often ineffective, and are complicated by significant toxicity. Therefore, there is significant interest in clinical interventional trials for glomerular disease (Table 3). The size of a clinical trial is driven primarily by the expected effect size and event frequency. Heterogeneous cohorts defined by histopathology alone are workable only if the therapeutic target is integral to a biologically meaningful common pathway. The good news is that research has progressed to the point where some specific disease cohorts, like that for MN, might have specific biomarker targets as mentioned above. However, we are not so fortunate for many other types of glomerular disease. Even diseases like Alport syndrome, where the genetic defect has been identified, pose difficulties for studying treatment because of slow progression and our poor knowledge of its natural history.

Table 3.

United States glomerular disease trials ongoing or completed within the last 5 years

| Trial Name | Disease(s) | Intervention | Sponsor | Recruitment Target | Ongoing/Completed |

| RAMP Study | Children with frequent relapsing or steroid-dependent NS | Rituximab versus mycophenolate mofetil | Nationwide Children’s Hospital/Genentech (South San Francisco, CA) | 64 | Ongoing |

| Rituximab + Cyclosporine in Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy | Idiopathic membranous nephropathy | Rituximab and cyclosporin | NIDDK NIH Clinical Center | 30 | Ongoing |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) in Patients with IgA Nephropathy | IgA nephropathy | Mycophenolate mofetil versus placebo | St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix | 184 (52 randomized) | Completed; results published |

| A Study of Fresolimumab in Patients with Steroid-Resistant Primary Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) | FSGS | Fresolimumab versus placebo | Genzyme | 36 | Completed; results not yet published |

| MENTOR | Membranous nephropathy | Cyclosporin A versus rituximab | Mayo Clinic | 126 | Ongoing; in follow-up phase |

| DUET | FSGS | Sparsentan versus placebo | Retrophin | 100 | Ongoing |

| Safety and Efficacy of Abatacept in Adults and Children with FSGS or MCD | FSGS and MCD | Abatacept | Bristol-Meyers Squibb (Princeton, NJ) | 90 | Ongoing |

| ACCESS | Lupus nephritis | CTLA4Ig (abatacept) plus cyclophosphamide versus cyclophosphamide alone | NIAID | 137 | Completed; results published |

| Laquinimod Study in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Patients with Active Lupus Nephritis | Lupus nephritis | Laquinimod combined with mycophenolate mofetil and steroids | Teva Pharmaceutical Industries | 47 | Completed; results not yet published |

| Efficacy and Safety Study of Abatacept to Treat Lupus Nephritis | Lupus nephritis | BMS-188667 (abatacept) or placebo with mycophenolate mofetil and corticosteroids | Bristol-Myers Squibb | 400 | Ongoing |

| AURA-LV | Lupus nephritis | Voclosporin (23.7 or 39.5 mg twice a day) versus placebo | Aurinia Pharmaceuticals Inc. | 258 | Ongoing |

| Rituximab and Belimumab for Lupus Nephritis | Lupus nephritis | Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide followed by belimumab | NIAID | 40 | Ongoing |

| BLISS-LN | Lupus nephritis | Belimumab plus standard of care versus placebo plus standard of care | Human Genome Sciences Inc. (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, United Kingdom) | 464 | Ongoing |

| TULIP-LN1 | Lupus nephritis | Two doses of anifrolumab versus placebo | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (Wilmington, DE) | 150 | Ongoing |

| A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Obinutuzumab, an Antibody Targeting Certain Types of Immune Cells, in Participants with Lupus Nephritis (LN) | Lupus nephritis | Obinutuzumab | Hoffmann-La Roche | 120 | Ongoing |

| Efficacy and Safety Study of Abatacept to Treat Lupus Nephritis | Lupus nephritis | Abatacept versus placebo on a background of mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticosteroids | Bristol-Myers Squibb | 423 | Completed; results published |

| Clinical Trial to Evaluate Safety and Efficacy of CCX168 in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis | ANCA-associated vasculitis | Two-dose regimens of the complement C5a receptor CCX168 | ChemoCentryx | 42 | Ongoing |

| Safety and Efficacy Study of Fostamatinib to Treat Immunoglobin A (IgA) Nephropathy | IgA nephropathy | Fostamatinib | Rigel Pharmaceuticals | 75 | Ongoing |

Search of ClinicalTrials.gov was limited to the United States, phase 2 or 3, and recruitment of ≥30 participants. RAMP, Randomized Trial Comparing Rituximab Against Mycophenolate Mofetil in Children Wtih Refractory Nephrotic Syndrome; NS, nephrotic syndrome; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIH, National Institutes of Health; MENTOR, MEmbranous Nephropathy Trial Of Rituximab; DUET, Randomized, Double-Blind, Safety and Efficacy Study of RE-021 (Sparsentan) in FSGS; MCD, minimal change disease; ACCESS, Abatacept and Cyclophosphamide Combination Therapy for Lupus Nephritis; CTLA4Ig, abatacept; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; AURA-LV, Aurinia Urinary Protein Reduction Active—Lupus with Voclosporin; BLISS-LN, Efficacy and Safety of Belimumab in Patients with Active Lupus Nephritis; TULIP-LN1, Safety and Efficacy of Two Doses of Aifrnolumab Compared with Placebo in Adult Subjects with Active Proliferative Lupus Nephritis.

The possibility of conducting pragmatic trials rather than the classic RCTs to test marketed drugs in patients with glomerular diseases has been raised. Pragmatic trials compare medical interventions under usual conditions of care in a broad population of patients with the disease of interest (26,27). Pragmatic trials and comparative effectiveness research may be useful in some contexts of study in primary glomerular disease, such as testing the effect of differing durations of common therapies or comparing two commonly prescribed second–line therapies. However, given the rarity and heterogeneity of primary glomerular diseases as well as the significant toxicities of current therapies, efforts should also focus on improving the phenotyping of patients with these diseases and developing more personalized medical interventions.

Some proposed changes to the regulation of clinical trials may contribute to more efficient execution. The intent of the proposed changes to the Common Rule is to reduce unnecessary burden and calibrate the oversight to the risk level, while enhancing the safeguards for research participants. Of particular relevance to glomerular disease trials, which require a large number of participating sites, because these are rare diseases, is the proposed use of a single IRB to facilitate multisite involvement (28). Examples of attempts to streamline IRB approval already exist. Recently, the concept of reliant review has been implemented by some consortia of institutions and community partners (29) and the NephCure Accelerating Cures Institute. Reliant review allows one IRB, designated as the IRB of record, to be responsible for reviewing, approving, and monitoring a study across its lifecycle. The process requires a single IRB submission to the IRB of record by the lead investigator. Collaborating IRBs agree to rely on the analyses of the IRB of record but assure compliance with institution-specific policies. Electronic IRB platforms can be used, which securely connect participating sites to a hub with all study documents and reviews from the IRB of record. Reliant review facilitates collaboration between investigators at multiple institutions, increases the population available for recruitment, and removes regulatory barriers by eliminating the need for independent human subjection protection review at multiple study sites. Other models include the use of a central IRB, independent of the participating sites (e.g., Western IRB or Chesapeake Research Review, Inc.). If the Common Rule proposal goes into effect, the use of a single IRB will be required rather than a piecemeal voluntary occurrence. There is the need to engage all stakeholders in clinical trial development—regulatory agencies, academics, industry, and patient advocacy organizations—as well as the opportunity to develop and obtain information from EHRs and informatics platforms (30).

Conclusions

Although many RCTs have led to advances in the understanding and treatment of inflammatory glomerulonephritides, such as lupus nephritis and ANCA-associated nephritis (31,32), this has not been duplicated in the primary glomerular diseases. As a community, nephrologists have to address the practices that might impair successful implementation of clinical trials. If possible, all or most patients with glomerular diseases should be offered the opportunity to enroll in a clinical trial if standard therapies have failed or are lacking. The ad hoc approaches that result from thinking “I know how to treat this disease best” fail to create the culture and the knowledge base needed to improve the management of this patient population. Training programs to develop a core group of kidney specialists with expertise in design and implementation of clinical trials are needed. Where practical, fostering relationships with nephrologists outside of large academic centers along with improved infrastructure would likely facilitate patient accrual into studies. Additional consideration needs to be given to the use of EHRs to streamline the collection of data on the natural history of a disease and use it to inform trial design. Industry partners need to see that the nephrology community is engaged in these strategies to improve participant enrollment into trials to ensure success.

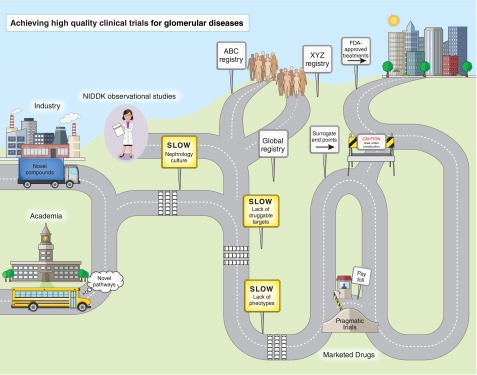

Lessons learned in a multinational, multicenter, RCT designed to identify a marketed therapy protective against cardiovascular events in patients on hemodialysis are also applicable to glomerular disease trials (33). The commentary emphasized the need for stratification for key prognostic factors, avoidance of treatment crossover during the trial, enhanced engagement of site investigators and study participants in a long-term trial, and the need to educate the nephrology community to avoid prescribing therapeutic agents without evidence-based efficacy. Development of new glomerular disease therapies has been hindered by poor understanding of their molecular mechanisms and reliance on histopathology as key entry criteria into clinical trials. Recent identification of familial (Mendelian) FSGS and genes associated with treatment-resistant MCD, the target podocyte antigen characterizing MN, and the association of apoL1 variants with disease risk in black participants with glomerular disease provides indisputable evidence that multiple specific disease processes can present with indistinguishable glomerular histopathology. The ability to phenotype patients with glomerular diseases on a molecular level will allow these novel targets to be used for therapeutic testing. This along with the progress being made in establishing high–quality glomerular disease registries and consortia (Figure 1) offer significant hope for our ability to conduct higher–quality and more efficient future clinical trials that will lead to more effective therapies for this patient population.

Figure 1.

Industry and academia are two different origins, but their roads must merge to get to the destination. Nephrology-specific barriers (culture, lack of druggable targets, and lack of phenotypes) are shown as speed bumps with accompanying slow signs. Multiple registries (ABC and XYZ) need to merge into a global registry along with information from the observational studies. Surrogate end points are a potential shortcut, but this road is still under construction. Pragmatic trials are a toll bridge, because they are not appropriate for novel target agents but may be useful for comparing marketed therapies.

Disclosures

M.M.M.-M. and M.F.F. have National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; Bethesda, MD) oversight for the Cure Glomerulonephropathy (CureGN) and the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) studies. L.H. is funded by the NIDDK as a principal investigator for CureGN, a site principal investigator for NEPTUNE, and a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, United Kingdom), Pfizer (New York, NY), and Bristol-Meyers Squibb (Princeton, NJ). F.K. is a site principal investigator for CureGN and NEPTUNE studies. J.R.S. is funded by the NIDDK and serves as a site principal investigator for NEPTUNE and CureGN and a consultant for Bristol-Meyers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Genzyme (Framingham, MA), and Third Rock Ventures (Boston, MA). J.R.S. is on the Scientific Advisory Board for the Phase II Treatment Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome Trial with Abatacept by Bristol-Myers Squibb. W.E.S. is funded by the NIDDK as a principal investigator for CureGN, has received funding from Genentech (South San Francisco, CA) as a principal investigator on the Randomized Trial Comparing Rituximab Against Mycophenolate Mofetil in Children With Refractory Nephrotic Syndrome Trial, and is coprincipal investigator of the Ohio State University Clinical and Translational Science Awards. A.M.T. and L.Y. have no disclosures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Jenna Norton for drafting the figure concept. There was no financial support provided for this function. Ms. Norton works in the Division of Kidney, Urology and Hematology with Dr. Moxey-Mims.

This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views or policies of the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00540116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Strippoli GFM, Craig JC, Schena FP: The number, quality, and coverage of randomized controlled trials in nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 411–419, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Zeeuw D, de Graeff PA: Clinical trial in nephrology at hard end point? J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 506–508, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inrig JK, Califf RM, Tasneem A, Vegunta RK, Molina C, Stanifer JW, Chiswell K, Patel UD: The landscape of clinical trials in nephrology: A systematic review of Clinicaltrials.gov. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 771–780, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuels JA, Molony DA: Randomized controlled trials in nephrology: State of the evidence and critiquing the evidence. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 19: 40–46, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Himmelfarb J: Chronic kidney disease and the public health: Gaps in evidence from interventional trials. JAMA 297: 2630–2633, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris M, Norwood V, Radeva M, Gassman JJ, Al-Uzri A, Askenazi D, Matoo T, Pinsk M, Sharma A, Smoyer W, Stults J, Vyas S, Weiss R, Gipson D, Kaskel F, Friedman A, Moxey-Mims M, Trachtman H: Patient recruitment into a multicenter randomized clinical trial for kidney disease: Report of the focal segmental glomerulosclerosis clinical trial (FSGS CT). Clin Transl Sci 6: 13–20, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levey AS, Cattran D, Friedman A, Miller WG, Sedor J, Tuttle K, Kasiske B, Hostetter T: Proteinuria as a surrogate outcome in CKD: Report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 205–226, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronco P: Moderator’s view: Biomarkers in glomerular diseases--translated into patient care or lost in translation? Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 899–902, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson A, Cattran DC, Blank M, Nachman PH: Complete and partial remission as surrogate end points in membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2930–2937, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck LH Jr., Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, Beck DM, Powell DW, Cummins TD, Klein JB, Salant DJ: M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 361: 11–21, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lalwani P, de Souza GKBB, de Lima DSN, Passos LFS, Boechat AL, Lima ES: Serum thiols as a biomarker of disease activity in lupus nephritis. PLoS One 10: e0119947, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birmingham DJ, Bitter JE, Ndukwe EG, Dials S, Gullo TR, Conroy S, Nagaraja HN, Rovin BH, Hebert LA: Relationship of circulating anti-C3b and anti-C1q IgG to lupus nephritis and its flare. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 47–53, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.O'Reilly VP, Wong L, Kennedy C, Elliot LA, O'Meachair S, Coughlan AM, O'Brien EC, Ryan MM, Sandoval D, Connolly E, Dekkema GJ, Lau J, Abdulahad WH, Sanders JF, Heeringa P, Buckley C, O'Brien C, Finn S, Cohen CD, Lindemeyer MT, Hickey FB, O'Hara PV, Feighery C, Moran SM, Mellotte G, Clarkson MR, Dorman AJ, Murray PT, Little MA: Urinary soluble CD163 in active renal vasculitis [published online ahead of print March 3, 2016]. J Am Soc Nephrol doi:10.1681/ASN.2015050511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gipson DS, Trachtman H, Kaskel FJ, Radeva MK, Gassman J, Greene TH, Moxey-Mims MM, Hogg RJ, Watkins SL, Fine RN, Middleton JP, Vehaskari VM, Hogan SL, Vento S, Flynn PA, Powell LM, McMahan JL, Siegel N, Friedman AL: Clinical trials treating focal segmental glomerulosclerosis should measure patient quality of life. Kidney Int 79: 678–685, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gipson DS, Trachtman H, Kaskel FJ, Greene TH, Radeva MK, Gassman JJ, Moxey-Mims MM, Hogg RJ, Watkins SL, Fine RN, Hogan SL, Middleton JP, Vehaskari VM, Flynn PA, Powell LM, Vento SM, McMahan JL, Siegel N, D’Agati VD, Friedman AL: Clinical trial of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children and young adults. Kidney Int 80: 868–878, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osafo C, Raji YR, Burke D, Tayo BO, Tiffin N, Moxey-Mims MM, Rasooly RS, Kimmel PL, Ojo A, Adu D, Parekh RS; H3 Africa Kidney Disease Research Network Investigators as members of The H3 Africa Consortium: Human heredity and health (H3) in Africa Kidney Disease Research Network: A focus on methods in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2279–2287, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coffey CS, Levin B, Clark C, Timmerman C, Wittes J, Gilbert P, Harris S: Overview, hurdles, and future work in adaptive designs: Perspectives from a National Institutes of Health-funded workshop. Clin Trials 9: 671–680, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research: FDA Draft Guidance for Industry: Adaptive Design Clinical Trials for Drugs and Biologics, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/ucm201790.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016

- 19.Food and Drug Administration: 110-85 (Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act), and Permanently Reauthorized in 2012 by Pub. L. 112-114 (Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act), 2012

- 20.Food and Drug Administration: Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, Pub. L. 107-109 (2002). Reauthorized in 2007 by Pub. L. 110-85 (Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act), and Permanently Reauthorized in 2012 by Pub. L. 112-114 (Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act), 2012

- 21.Food and Drug Administration: Pediatric Research Equity Act. Pub L. 108-155 (2003). Reauthorized in 2007 by Pub. L. 110-85 (Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act), and Permanently Reauthorized in 2012 by Pub. L. 112-114 (Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act), 2012

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Specific Requirements on Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drugs; Revision of “pediatric use” Subsection In the Labeling, Final Rule. Federal Register Volume 59, Number 238 (Tuesday, December 13, 1994) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Food and Drug Administration: Specific requirements on content and format of labeling for human prescription drugs: Revision of “pediatric use” subsection in the labeling: Final rule. Fed Regist 59: 238, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunne J, Rodriguez WJ, Murphy MD, Beasley BN, Burckart GJ, Filie JD, Lewis LL, Sachs HC, Sheridan PH, Starke P, Yao LP: Extrapolation of adult data and other data in pediatric drug-development programs. Pediatrics 128: e1242–e1249, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coorevits P, Sundgren M, Klein GO, Bahr A, Claerhout B, Daniel C, Dugas M, Dupont D, Schmidt A, Singleton P, De Moor G, Kalra D: Electronic health records: New opportunities for clinical research. J Intern Med 274: 547–560, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan GM: Getting off the “gold standard”: Randomized controlled trials and education research. J Grad Med Educ 3: 285–289, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JH, Hamel MB: Pragmatic trials--guides to better patient care? N Engl J Med 364: 1685–1687, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson KL, Collins FS: Bringing the common rule into the 21st century. N Engl J Med 373: 2293–2296, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cola PA, Reider C, Strasser JE: Ohio CTSAs implement a reliant IRB model for investigator-initiated multicenter clinical trials. Clin Transl Sci 6: 176–178, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reith C, Landray M, Devereaux PJ, Bosch J, Granger CB, Baigent C, Califf RM, Collins R, Yusuf S: Randomized clinical trials--removing unnecessary obstacles. N Engl J Med 369: 1061–1065, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris HK, Canetta PA, Appel GB: Impact of the ALMS and MAINTAIN trials on the management of lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1371–1376, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogan J, Avasare R, Radhakrishnan J: Is newer safer? Adverse events associated with first-line therapies for ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1657–1667, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkovic V, Neal B: Trials in kidney disease--time to EVOLVE. N Engl J Med 367: 2541–2542, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.