Abstract

Background and objectives

The majority of older adults who initiate dialysis do so during a hospitalization, and these patients may require post-acute skilled nursing facility (SNF) care. For these patients, a focus on nondisease-specific problems, including cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, falls, impaired mobility, and polypharmacy, may be more relevant to outcomes than the traditional disease-oriented approach. However, the association of the burden of nondisease-specific problems with mortality, transition to long-term care (LTC), and functional impairment among older adults receiving SNF care after dialysis initiation has not been studied.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We identified 40,615 Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old who received SNF care after dialysis initiation between 2000 and 2006 by linking renal disease registry data with the Minimum Data Set. Nondisease-specific problems were ascertained from the Minimum Data Set. We defined LTC as ≥100 SNF days and functional impairment as dependence in all four essential activities of daily living at SNF discharge. Associations of the number of nondisease-specific problems (≤1, 2, 3, and 4–6) with 6-month mortality, LTC, and functional impairment were examined.

Results

Overall, 39.2% of patients who received SNF care after dialysis initiation died within 6 months. Compared with those with ≤1 nondisease-specific problems, multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for mortality were 1.26 (1.19 to 1.32), 1.40 (1.33 to 1.48), and 1.66 (1.57 to 1.76) for 2, 3, and 4–6 nondisease-specific problems, respectively. Among those who survived, 37.1% required LTC; of those remaining who did not require LTC, 74.7% had functional impairment. A higher likelihood of transition to LTC (among those who survived 6 months) and functional impairment (among those who survived and did not require LTC) was seen with a higher number of problems.

Conclusions

Identifying nondisease-specific problems may help patients and families anticipate LTC needs and functional impairment after dialysis initiation.

Keywords: geriatric nephrology, dialysis, mortality, Accidental Falls, Activities of Daily Living, Cognition Disorders, depression, hospitalization, Humans, Long-Term Care, Medicare, Patient Discharge, Polypharmacy, Registries, renal dialysis, Skilled Nursing Facilities, United States

Introduction

The majority of older adults initiating dialysis do so during a hospitalization, and these patients may require post-acute care services in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) (1,2). Although previous studies of older patients receiving dialysis have reported high-intensity hospital care at the time of dialysis initiation and poor health outcomes after dialysis initiation among nursing home residents (2–4), descriptions of community-dwelling older adults who begin dialysis during a hospitalization and receive subsequent SNF care are limited (5). Because older patients initiating dialysis are medically complex and dialysis can interfere with rehabilitation, they may experience worsening health and may not return home or achieve functional independence (6,7).

Routine clinical care for patients initiating dialysis follows the traditional disease-oriented model, which emphasizes the recognition of signs and symptoms related to kidney failure or other discrete medical conditions. In contrast, a geriatric approach to patient care emphasizes the recognition of symptoms, impairments, and treatment-related problems that are often not the result of a single underlying disease, but contribute to functional impairment and need for nursing home care. The term “nondisease-specific” has been used to describe such health problems that cross multiple domains of health, but are not a focus of disease-specific medical care. Previous studies have shown that six nondisease-specific problems (cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, falls, impaired mobility, and polypharmacy) were common among older adults with earlier stages of CKD and associated with poor health outcomes (8,9).

The purpose of the current analysis was to examine the association of the burden of co-occurring nondisease-specific problems with mortality, transition to long-term care (LTC), and functional impairment among older adults who required post-acute SNF care after initiation of dialysis. To address this aim we designed a retrospective cohort study of older incident dialysis patients obtained from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) linked to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set (CMS MDS), a national registry of patients receiving post-acute SNF care and LTC that includes comprehensive assessments of nondisease-specific problems.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Participants

Data were obtained through the USRDS and included the CMS Medical Evidence Report Form, CMS-2728, linked to the CMS LTC MDS 2.0. Completion of the CMS-2728 form is required within 45 days of the first maintenance RRT for all patients with ESRD, regardless of current or future intention to use Medicare services (10,11). The CMS LTC MDS is a standardized, primary screening and assessment tool of health status for all residents admitted to a Medicare or Medicaid certified nursing home (encompassing 95% of all United States nursing homes), regardless of payer (12,13). The MDS assessment is conducted on admission, quarterly, and annually, as well as after a significant change in status, such as SNF discharge.

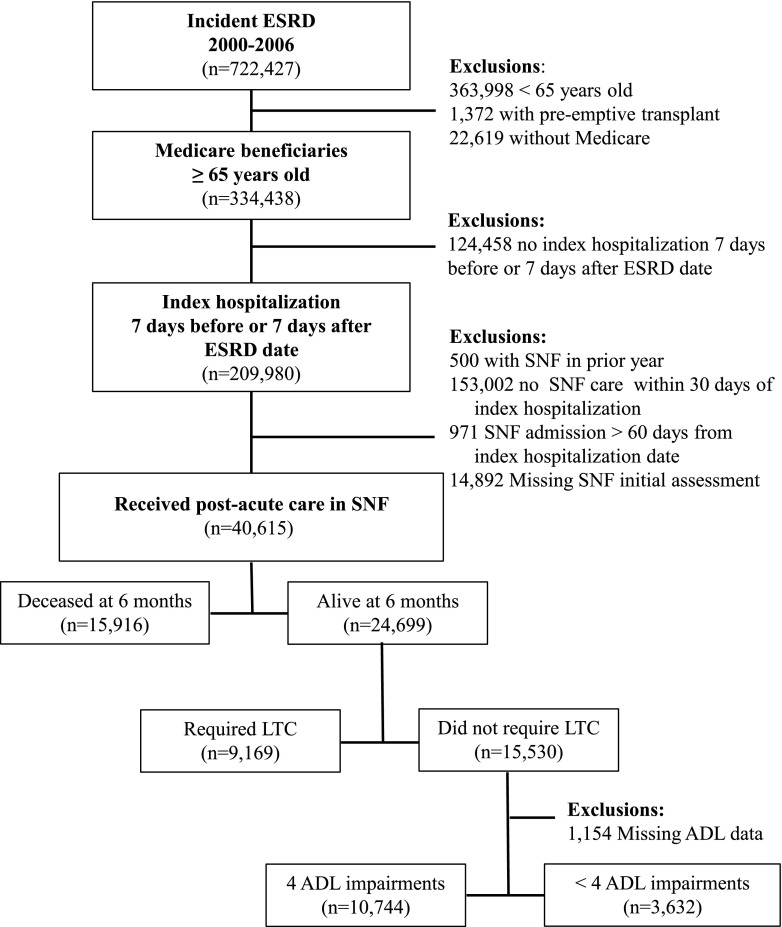

The cohort included Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years of age who initiated dialysis between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2006 (n=334,438). Using Medicare inpatient hospitalization data, we identified 209,980 patients with an index hospitalization within 7 days before or after the ESRD date on the CMS-2728. In order to identify those who required SNF care after initiation of dialysis, we excluded those who may have been receiving SNF care or LTC before dialysis initiation (i.e., MDS data indicating nursing home care in the year before the ESRD date; n=500), those who did not receive post-acute SNF care (i.e., no MDS data within 30 days of dialysis initiation; n=153,002), those admitted to an SNF >60 days after the ESRD date (n=971), and those with MDS data but missing the initial MDS assessment (n=14,892), yielding a final analytic cohort of 40,615 patients on dialysis (Figure 1). The median time between ESRD date and SNF admission was 12 days (interquartile range, 7–20). Characteristics of patients with and without an MDS assessment at the time of SNF admission are displayed in Supplemental Table 1. This study protocol was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Among Medicare beneficiaries >65 years old with a index hospitalization at the time of dialysis initiation, use of post-acute SNF care was common. Cohort selection and health outcomes for 40,615 patients on dialysis who received post-acute care in an SNF after an index hospitalization at the time of incident ESRD. ADL, activities of daily living; LTC, long-term care; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Nondisease-Specific Problems

Data on nondisease-specific problems were obtained from the MDS assessment at SNF admission, and included cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, falls, impaired mobility, and polypharmacy. Definitions for these problems were adapted from previous studies and on the basis of available data from the MDS (8,9). The Cognitive Performance Scale is a validated cognitive assessment tool included in the MDS. Scores range from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating worse cognitive impairment. Consistent with previous research, we defined cognitive impairment as scores ≥3, which includes moderate to very severe impairment (14). Patients were identified as having depressive symptoms if the MDS indicated they had “withdrawal from activities of interest” or “one or more indicators of depressed, sad, or anxious mood.” Exhaustion was defined as “not awake most of the time” for morning, afternoon, or evening. Falls were defined as a fall within either the “past 30 days” or “past 31–180 days.” Impaired mobility was defined as “wheelchair primary mode of locomotion.” Polypharmacy was defined as the upper tertile of medication use (≥14 medications).

Other Variables

Data on demographic- and health-related characteristics were obtained from both the CMS-2728 and the MDS. Age, sex, ethnicity, race, Medicaid coverage, region of residence (Northeast, South, Midwest, West), primary cause of renal failure, cardiovascular conditions, laboratory values, predialysis nephrology care (from the 2005 version of the CMS-2728), and dialysis treatment characteristics were obtained from the CMS-2728. The presence of AKI was defined as any discharge diagnosis of acute kidney failure (International Classification of Diseases 9th revision codes: 584.5–584.9) for the index hospitalization. Data on marital status, living status (i.e., living alone), and other comorbid conditions (including arthritis, hip fracture, amputations, Alzheimer disease and other dementias, lung disease, and cancer) were obtained from the MDS.

Mortality, LTC, and Functional Impairment

The outcomes were assessed in the first 6 months after the ESRD initiation date. This time frame was chosen because of the early mortality associated with dialysis initiation and to capture SNF use most likely to be related to the index hospitalization and dialysis initiation, rather than long-term complications of ESRD or unrelated hospitalizations (15–17). Mortality subsequent to the ESRD date was determined using data from the USRDS that includes the CMS ESRD Death Notification (CMS-2746) and Social Security Death Index. Completion of the CMS-2746 is required when patients with ESRD die, regardless of payer status. Transition from post-acute SNF care to LTC was defined as requiring ≥100 total days in the nursing home. This definition is on the basis of the Medicare Part A SNF benefit, which covers the full cost for days 1–20 and all but a daily copayment for days 21–100 if the patient continues to meet Medicare’s SNF requirement (1). Among those who did not require LTC, functional impairment was defined as requiring assistance with all four essential activities of daily living (ADLs), which include bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring ascertained from the MDS assessment at the time of SNF discharge. Independence in all essential ADLs is necessary to live alone (18).

Statistical Analyses

Demographic, health, and dialysis treatment characteristics were calculated as proportions or means and SD, as appropriate. The prevalence of each nondisease-specific problem and the co-occurrence of nondisease-specific problems (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4–6) were calculated. Those with 4–6 problems were combined because of the small numbers with 5 and 6 problems. The associations between nondisease-specific problems and mortality, transition to LTC, and functional impairment were assessed using three study populations. First, the entire cohort (n=40,615) was analyzed to determine the association between number of nondisease-specific problems and all-cause mortality. The percentage of patients who died within 6 months was calculated according to number of nondisease-specific problems. The association between the co-occurrence of nondisease-specific problems (2, 3, and 4–6, compared with ≤1) and 6-month mortality was examined using Cox proportional hazard models. We calculated hazard ratios both with and without adjustment for a priori potential confounders, including age, sex, ethnicity, race, Medicaid coverage, region of residence, living alone, marital status (married versus not married), primary cause of ESRD, cardiovascular conditions, other comorbid conditions, serum albumin, serum creatinine, and hemoglobin. Patients were followed until the time of death or 6 months after dialysis initiation. Next, we used the subset of the cohort who were alive at 6 months (n=24,699) to determine the association between number of nondisease-specific problems and transition to LTC. Because the Medicare SNF benefit can include nonconsecutive SNF days, we limited this analysis to patients who survived at least 6 months to capture those who may have required hospitalization and returned to the SNF. We calculated the percentage of patients who required LTC according to number of nondisease-specific problems, and calculated odds ratios using logistic regression. We used crude and multivariable models as described for the mortality analysis. Finally, limiting the study population to those who survived 6 months, did not require LTC, and had available ADL data at SNF discharge (n=14,376), we determined the association between number of nondisease-specific problems and impairment in all four essential ADLs, using the same method described for the transition to LTC analysis. SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Demographic, health and treatment characteristics of all patients who required post-acute SNF care after inpatient dialysis start are displayed in Table 1. Patients had a mean age of 77.4 years and 54.5% were women. The percentage of patients with any discharge diagnosis of acute kidney failure was 21.7%. The majority of patients had ≥1 nondisease-specific problems. The prevalence of 1, 2, 3, and 4–6 nondisease-specific problems was 21.5%, 31.8%, 24.9%, and 15.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 40,615 US Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years of age at admission to a SNF after inpatient initiation of dialysis between 2000 and 2006

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 77.4 (6.7) |

| Women | 22,001 (54.5) |

| Race | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2205 (5.5) |

| White | 31,372 (77.9) |

| Black | 7656 (19.0) |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 276 (0.7) |

| Asian | 560 (1.4) |

| Other | 428 (1.1) |

| Medicaid | 8789 (21.8) |

| Region of residence | |

| Northeast | 10,046 (24.8) |

| South | 10,797 (26.6) |

| Midwest | 14,582 (36.0) |

| West | 5131 (12.7) |

| Lived alonea | 12,464 (30.8) |

| Marital statusa | |

| Never married | 3284 (8.1) |

| Married | 15,739 (39.0) |

| Widowed | 17,536 (43.4) |

| Separated | 659 (1.6) |

| Divorced | 3173 (7.9) |

| Health characteristics | |

| Primary cause of renal failure | |

| Diabetes | 17,061 (42.3) |

| GN | 1421 (3.5) |

| Secondary GN/vasculitis | 430 (1.1) |

| Interstitial nephritis | 1451 (3.6) |

| Hypertension/large vessel | 14,069 (34.9) |

| Cystic/hereditary/congenital | 201 (0.5) |

| Neoplasms/tumors | 914 (2.3) |

| Other | 4817 (11.9) |

| Cardiovascular conditions | |

| Congestive heart failure | 20,468 (50.7) |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 15,651 (38.8) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6612 (16.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 9033 (22.4) |

| Other | 9916 (24.6) |

| Other comorbid conditionsa | |

| Arthritis | 7293 (18.0) |

| Hip fracture | 1034 (2.6) |

| Missing limb | 2030 (5.0) |

| Alzheimer disease | 653 (1.6) |

| Dementia other than Alzheimer disease | 4009 (9.9) |

| Emphysema/COPD | 8617 (21.2) |

| Cancer | 4125 (10.2) |

| Serum albumin, g/dlb | 2.9 (0.6) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dlb | 5.6 (2.6) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dlb | 10.0 (1.6) |

| Treatment characteristics | |

| Primary type of dialysis | |

| Hemodialysis | 39,974 (99.1) |

| CAPD | 240 (0.6) |

| CCPD | 101 (0.3) |

| Other | 29 (0.1) |

| Predialysis nephrology carec | 4398 (51.2) |

| Individual nondisease-specific problemsa | |

| Cognitive impairment | 7818 (19.3) |

| Depressive symptoms | 12,865 (31.7) |

| Exhaustion | 20,703 (51.0) |

| Falls | 10,199 (25.1) |

| Impaired mobility | 27,504 (67.7) |

| Polypharmacy (≥14 medications) | 13,034 (32.1) |

| Number of nondisease-specific problemsa | |

| 0 | 2472 (6.1) |

| 1 | 8749 (21.5) |

| 2 | 12,922 (31.8) |

| 3 | 10,107 (24.9) |

| 4–6 | 6365 (15.7) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CCPD, continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Patient characteristics from the CMS Minimum Data Set. All other characteristics obtained from the CMS-2728.

Data is presented as mean (SD).

Available on the 2005 version of the CMS-2728 for 8590 patients.

Mortality

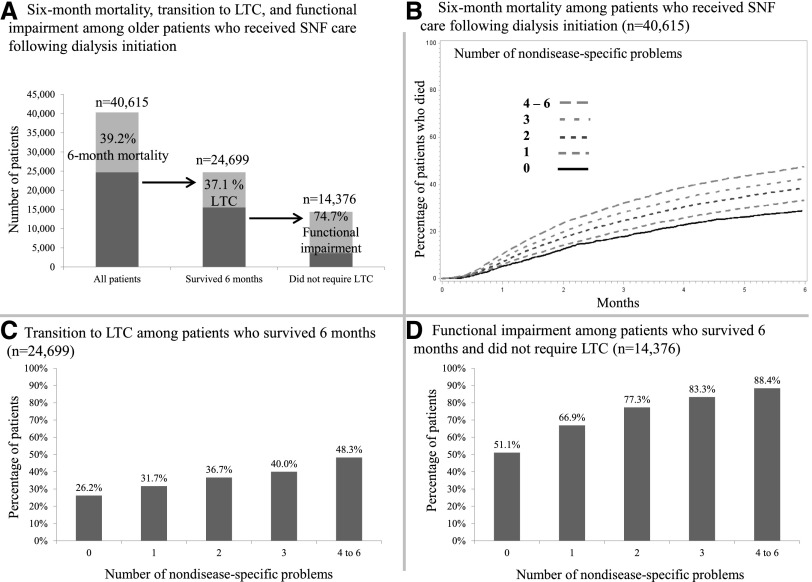

Overall, 39.2% (n=15,916) of our study cohort died within 6 months (Figure 2A, left bar). The percentage of patients who died within 6 months was higher at a higher number of nondisease-specific problems (Figure 2B). Compared with those who had ≤1 nondisease-specific problem, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) for mortality was 1.26 (1.19 to 1.32), 1.40 (1.33 to 1.48), and 1.66 (1.57 to 1.76) for patients with 2, 3, and 4–6 nondisease-specific problems, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The proportion of patients who died, transitioned to LTC, or had functional impairment was greater at higher number of nondisease-specific problems. (A) Death, transition to long-term care (LTC), and functional impairment were common among older adults who required skilled nursing facility (SNF) care after dialysis initiation. At higher numbers of nondisease-specific problems, a greater percentage of patients died (B), transitioned to LTC among those who survived 6 months (C), and had functional impairment among those who survived 6 months and did not require LTC (D).

Table 2.

Associations of nondisease-specific problems and mortality, long-term care, and functional impairment among older adults who require skilled nursing care after dialysis initiation

| Number of Nondisease-Specific Problems | ||||

| 0 to 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 to 6 | |

| Mortality among patients who received SNF care following dialysis initiation (n=40,615) | ||||

| Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 1.25 (1.20, 1.31) | 1.43 (1.36, 1.49) | 1.67 (1.60, 1.76) |

| Multivariable Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 1.26 (1.19, 1.32) | 1.40 (1.33, 1.48) | 1.66 (1.57, 1.76) |

| Transition to LTC among patients who survived 6 months (n=24,699) | ||||

| Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 1.32 (1.24, 1.41) | 1.52 (1.42, 1.64) | 2.14 (1.97, 2.32) |

| Multivariable Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 1.33 (1.22, 1.45) | 1.56 (1.42, 1.71) | 2.17 (1.95, 2.41) |

| Functional impairment among patients who survived 6 months and did not require LTC (n=14,376) | ||||

| Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 2.00 (1.83, 2.19) | 2.92 (2.62, 3.26) | 4.48 (3.78, 5.31) |

| Multivariable Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 1.87 (1.68, 2.09) | 2.84 (2.48, 3.26) | 4.40 (3.54, 5.46) |

Multivariable adjustment includes age, sex, ethnicity, race, Medicaid coverage, region of residence, living alone, marital status (married vs not married), primary cause of dialysis, cardiovascular disease comorbidity, other comorbidity, serum albumin, serum creatinine, and hemoglobin. SNF, skilled nursing facility; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; LTC, long-term care.

Transition to LTC

Among those who survived 6 months after dialysis initiation, 9169 (37.1%) required LTC (Figure 2A, center bar). The percentage transitioning to LTC was higher at a higher number of nondisease-specific problems (Figure 2C). This corresponded to a higher likelihood of transition to LTC: odds ratio (95% confidence interval), 1.33 (1.22 to 1.45), 1.56 (1.42 to 1.71), and 2.17 (1.95 to 2.41) for those with 2, 3, and 4–6 nondisease-specific problems, compared with ≤1, respectively.

Functional Impairment

Of those who survived 6 months and did not require LTC, 10,744 (74.7%) were dependent in all four essential ADLs (Figure 2A, right bar). A similar pattern of greater functional impairment at a higher number of nondisease-specific problems was found in the study population limited to those who did not require LTC (Figure 2D, Table 2).

Discussion

Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old who received SNF care immediately after dialysis initiation experienced high short-term mortality. Among those who survived 6 months, more than one in three patients required LTC. Among those who survived and did not require LTC, nearly three in four experienced functional impairment that would make it impossible to live alone. We also found a graded association of the risk of mortality, transition to LTC, and functional impairment with a higher number of nondisease-specific problems. Although these findings suggest an overall poor prognosis, recognizing the burden of nondisease-specific problems may be helpful for prognostication as part of shared decision-making discussions, and for tailoring care to manage these problems to improve quality of life.

Previous studies have shown a high prevalence of several individual nondisease-specific problems among older adults with kidney disease, and there is growing evidence of the significance of these problems for health outcomes (19,20). For example, falls have been shown to be common among patients with ESRD and are associated with risk for mortality and poor outcomes (21,22). Importantly, we found that a higher number of nondisease-specific problems was associated with higher risk for death, transition to LTC, and functional impairment. Additionally, previous studies have described the lack of data available on patients with ESRD in nursing homes, and studies that have been conducted have focused on those receiving LTC or among those discharged from SNF care (5,23). We studied the effect of nondisease-specific problems among older adults who were not institutionalized before dialysis initiation, of whom nearly one third were living alone before developing ESRD.

Findings from the current analysis have clinical implications for shared decision-making and providing anticipatory care. A higher burden of nondisease-specific problems was found to be associated with a greater likelihood of transition from SNF care to LTC and functional impairment. Many older adults frame their health goals in terms of functional independence and prioritize remaining independent in their homes and communities (24–26). Identifying nondisease-specific problems may provide important context in which to consider treatment options for kidney failure, support shared decision-making discussions, and prognostication after dialysis initiation. These findings, when taken together with previous studies that have shown limited survival benefit associated with dialysis initiation among older adults with multimorbidity and functional impairment (27,28), suggest that for older adults with a high burden of nondisease-specific problems who prioritize functional independence and avoiding LTC placement, dialysis may not help them meet their health goals. Future studies that include evaluation of nondisease-specific problems before and after dialysis initiation, and that compare dialysis and conservative management, are necessary to determine if conservative management without dialysis is an appropriate option for these patients. Regardless of RRT decisions, providing information on LTC use and functional impairment after dialysis initiation may support patients and families as they prepare for future health care and LTC needs.

In addition to supporting clinical decision making, evaluation for nondisease-specific problems may identify targets to improve outcomes for these patients. Geriatric assessment has been shown to improve recognition of these problems, and interdisciplinary approaches may reduce the effect of nondisease-specific problems on functional impairment and quality of life (29). Furthermore, because these assessments are brief and do not require special equipment they could easily be done before dialysis initiation or during an acute care hospitalization. Although post-acute SNF care, including physical and occupational therapy, aims to maximize and maintain functional status, our finding that nearly 75% of dialysis patients discharged from SNFs were dependent in all four essential ADLs may suggest that the current care model is not meeting the post-acute care goal (30). Integrative care models that include nephrology and geriatrics before patients transition from acute to post-acute settings, and follow these patients through SNF care, may improve functional outcomes for these patients. Future studies are necessary to determine if restructuring hospital and post-acute SNF care to address nondisease-specific problems may reduce the need for LTC in this population.

Strengths of this study included the linkage of national ESRD registry data with data from the MDS, which includes standardized, comprehensive assessments for nondisease-specific problems that are not routinely available for patients on dialysis. This analysis also included a large sample of older adults who required SNF care after dialysis initiation, and available longitudinal data to ascertain transition to LTC and functional impairment. However, there are also several limitations to consider. Previous studies have shown a low sensitivity for the CMS-2728 to identify several patient and treatment characteristics (4,31). Additionally, data for the initial MDS assessment and discharge ADL assessment were missing for 7% of those who did not require LTC. Although this analysis leverages a unique linkage between USRDS and MDS data, we were limited to those who initiated dialysis between 2000 and 2006. The majority of patients in the current analysis were white and findings may not be representative of the general dialysis population. Physical performance measures such as gait speed, which have been shown to be associated with functional decline, were not included in the CMS LTC MDS 2.0. We were interested in those who were community-dwelling before dialysis initiation and therefore did not have data on nondisease-specific problems preceding SNF care. It is not known if nondisease-specific problems would have had a similar prognostic value among patients who were not hospitalized in the time period around dialysis initiation, or those who did not receive post-acute SNF care. Although, the MDS Cognitive Performance Scale is a validated measure of cognition, several of the other MDS indicators of nondisease-specific problems have not been independently validated. Despite the likelihood for misclassification, we found a consistent higher risk for adverse health outcomes at a higher number of nondisease-specific problems.

In conclusion, the presence of multiple co-occurring nondisease-specific problems among older adults new to dialysis was associated with a higher risk for mortality, transition from SNF to LTC, and functional impairment. Because older adults often consider health goals and treatment preferences in the context of avoiding nursing home placement and maintaining functional independence, these findings may inform shared decision-making about dialysis initiation or post-acute care planning for older adults initiating dialysis during a hospitalization.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support was provided through National Institutes of Health contract no. N01-DK-7-5004 to N.K., and the Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research & Development (grant no. 1IK2CX000856-01A1 to C.B.B.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01260216/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Medicare Coverage of Skilled Nursing Facility Care, Baltimore, MD, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 143–149, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowling CB, Zhang R, Franch H, Huang Y, Mirk A, McClellan WM, Johnson TM 2nd, Kutner NG: Underreporting of nursing home utilization on the CMS-2728 in older incident dialysis patients and implications for assessing mortality risk. BMC Nephrol 16: 32, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall RK, O’Hare AM, Anderson RA, Colón-Emeric CS: End-stage renal disease in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14: 242–247, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M: Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 361: 1612–1613, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong EM, Nissenson AR: Dialysis in nursing homes. Semin Dial 15: 103–106, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowling CB, Booth JN 3rd, Gutiérrez OM, Kurella Tamura M, Huang L, Kilgore M, Judd S, Warnock DG, McClellan WM, Allman RM, Muntner P: Nondisease-specific problems and all-cause mortality among older adults with CKD: the REGARDS Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1737–1745, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowling CB, Booth JN 3rd, Safford MM, Whitson HE, Ritchie CS, Wadley VG, Cushman M, Howard VJ, Allman RM, Muntner P: Nondisease-specific problems and all-cause mortality in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 739–746, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggers PW: CMS 2728: what good is it? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1908–1909, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foley RN, Collins AJ: The USRDS: what you need to know about what it can and can’t tell us about ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 845–851, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koroukian SM, Xu F, Murray P: Ability of Medicare claims data to identify nursing home patients: a validation study. Med Care 46: 1184–1187, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R: Long-term care services in the United States: 2013 overview. Vital Health Stat 3 (37): 1–107, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V, Lipsitz LA: MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol 49: M174–M182, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, Anthony MS, Critchlow CW, Pisoni RL, Port FK, Gillespie BW: Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 89–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soucie JM, McClellan WM: Early death in dialysis patients: risk factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2169–2175, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Renal Data System: 2013 USRDS Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 63: A1–A8, e1–e478, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z: Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA 292: 2115–2124, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand S, Johansen KL, Kurella Tamura M: Aging and chronic kidney disease: the impact on physical function and cognition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 315–322, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurella Tamura M, Yaffe K: Dementia and cognitive impairment in ESRD: diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Kidney Int 79: 14–22, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farragher J, Chiu E, Ulutas O, Tomlinson G, Cook WL, Jassal SV: Accidental falls and risk of mortality among older adults on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1248–1253, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook WL, Tomlinson G, Donaldson M, Markowitz SN, Naglie G, Sobolev B, Jassal SV: Falls and fall-related injuries in older dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1197–1204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall RK, Toles M, Massing M, Jackson E, Peacock-Hinton S, O’Hare AM, Colón-Emeric C: Utilization of acute care among patients with ESRD discharged home from skilled nursing facilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 428–434, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling CB, Muntner P, Sawyer P, Sanders PW, Kutner N, Kennedy R, Allman RM: Community mobility among older adults with reduced kidney function: a study of life-space. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 429–436, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Cheung KL, Nair SS, Kurella Tamura M, Craig JC, Winkelmayer WC: Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver perspectives on end-of-life care in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 913–927, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H: Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med 346: 1061–1066, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM: Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 146: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, Phibbs C, Courtney D, Lyles KW, May C, McMurtry C, Pennypacker L, Smith DM, Ainslie N, Hornick T, Brodkin K, Lavori P: A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med 346: 905–912, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenq GY, Tinetti ME: Post-acute care: who belongs where? JAMA Intern Med 175: 296–297, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Martin AA, Fink NE, Powe NR: Validation of comorbid conditions on the end-stage renal disease medical evidence report: the CHOICE study. Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 520–529, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.