Abstract

Increases in inflammation, coagulation, and CD8+ T-cell numbers are associated with an elevated cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected antiretroviral therapy (ART) recipients. Circulating memory CD8+ T cells that express the vascular endothelium-homing receptor CX3CR1 (fractalkine receptor) are enriched in HIV-infected ART recipients. Thrombin-activated receptor (PAR-1) expression is increased in HIV-infected ART recipients and is particularly elevated on CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells, suggesting that these cells could interact with coagulation elements. Indeed, thrombin directly enhanced T-cell receptor–mediated interferon γ production by purified CD8+ T cells but was attenuated by thrombin-induced release of transforming growth factor β by platelets. We have therefore identified a population of circulating memory CD8+ T cells in HIV infection that may home to endothelium, can be activated by clot-forming elements, and are susceptible to platelet-mediated regulation. Complex interactions between inflammatory elements and coagulation at endothelial surfaces may play an important role in CVD risk in HIV-infected ART recipients.

Keywords: non–AIDS-related morbidities, CD8+ T-cell expansion, atherosclerosis, platelets

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection results in a marked expansion of circulating CD8+ T cells that does not normalize even after many years of antiretroviral therapy (ART) [1]. CD8+ T-cell persistence in treated HIV–infected donors contributes to abnormally low ratios of CD4+ T cells to CD8+ T cells (hereafter, “CD4+/CD8+ ratios”), now recognized as associated with a greater risk for morbidity, including cardiovascular events [2–5]. A relationship to vascular health is suggested by observations that an inverted CD4+/CD8+ ratio is also associated with greater intima media thickness and arterial stiffness, both of which are important predictors of cardiovascular morbidity [4, 6].

A recent study examined the characteristics of the expanded circulating CD8+ T cells in patients with inverted CD4+/CD8+ ratios despite sustaining CD4+ T-cell counts at >500 cells/µL during ART [3]. Inverted CD4+/CD8+ ratios were associated with higher indices of CD8+ T-cell activation, exhaustion, and immunosenescence [2, 3], and we have linked cytomegalovirus (CMV) coinfection to inflammation, CD8+ T-cell expansion, and inverted CD4+/CD8+ ratios in ART-treated HIV infection [7]. While CD8+ T-cell expansion in ART-treated HIV infection has been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD), neither the drivers of CD8+ lymphocytosis in this setting nor the underlying mechanisms for their link to increased cardiovascular risk are fully understood [1].

There is reason to suspect that CD8+ T cells play a role in CVD in both HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. CD8+ T cells can home and adhere to vascular endothelial and smooth-muscle cells through engagement of the fractalkine receptor, CX3CR1, to its ligand CX3CL1 that is expressed on activated endothelium [8–10]. Localization of immune cells to the vascular endothelium is likely an important step in atherogenesis, as polymorphisms in CX3CR1 have been shown to be associated with differential risk for atherosclerosis [11, 12]. CD8+ T cells have also been shown to form complexes with other cell types that localize to the vasculature [13]. Platelets are critical mediators of hemostasis, coagulation, and wound healing and can form conjugates with CD8+ T cells or other leukocytes [14]. Increased frequencies of platelet/leukocyte complexes have been observed in the peripheral blood of HIV-infected ART recipients, as well as in the blood of patients with CVD, type I diabetes, or systemic lupus erythematosus [14–17], yet the biological significance of these interactions, or the cross-talk that occurs among these cell types, remains to be determined.

Coagulation may affect interactions among platelets and CD8+ T cells. A critical step in coagulation occurs by the cleavage of prothrombin by factor X into thrombin [18]. In addition to promoting clot formation, thrombin can also cleave an extracellular portion of protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), subsequently activating the receptor through the newly generated N-terminus [19]. PAR-1 is expressed on the surface of CD8+ T cells as well as on monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells [20–22]. A recent report indicated that PAR-1 expression is increased on the surface of CD8+ T cells from treated HIV-infected patients and that PAR-1 activation directly increases CD8+ T-cell effector function [20].

In this study, we sought to explore further the mechanisms by which persistent CD8+ T-cell expansion in HIV-infected ART recipients is associated with CVD risk. We find that cellular interactions in this setting are more complex than appreciated. We demonstrate that circulating CD8+ T cells expressing the vascular homing receptor CX3CR1 and the thrombin-activated receptor PAR-1 are expanded in treated HIV infection; we also confirm that thrombin augments effector function in purified CD8+ T cells in vitro, yet, in the presence of platelets, CD8+ T-cell effector function is inhibited. This mechanism is dependent upon transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) release by PAR-1 activation of platelets, suggesting a potentially important immune regulatory aspect of thrombosis.

METHODS

Donors

This work was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (protocol 01-98-55) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. With informed consent, blood was acquired in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid or heparin from 17 HIV-uninfected persons or 35 HIV-infected ART recipients (median duration of therapy, 5.1 years) with undetectable plasma HIV (typically <40 copies/mL). CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts were determined in the hospital clinical laboratory by flow cytometry.

Tissue Processing

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from whole peripheral blood by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare) and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and 1% L-glutamine (Gibco) at 37°C and 5% CO2. For isolation of cells from lymph nodes, biopsy specimens were cut into small pieces, homogenized, and filtered, and cells were purified by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque as described above. T cells were further purified using the Pan T cell Isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and an AutoMACS Pro Separator (Miltenyi). Freshly harvested cells were used for all analyses.

Flow Cytometry

Lymphocytes and platelets were identified by forward and side scatter, and phenotype was assessed using the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: anti-CD3 (clone SK7; eBioscience), anti-CD4 (RPA-T4; BD Bioscience), anti-CD8 (RPA-T8; BD), anti-CD27 (O323; eBioscience), anti-CD45RA (L48; BD), anti-CD45RO (UCHL1; BD), anti-CD62P (AK-4; BD), anti-CCR7 (3D12; BD), anti-CX3CR1 (2A9-1; Biolegend), anti-KLRG1 (2F1; Biolegend), anti–PAR-1 (SPAN12; Beckman Coulter), anti–PD-1 (EH12.1; BD), anti–PSGL-1 (KPL-1; Biolegend), and anti–TGF-β (TW4-9E7; BD). Viable cells were gated using Live/Dead Yellow viability dye (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were stained for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature, washed, and fixed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% formaldehyde. All samples were acquired on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD). For detection of intracellular cytokines, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 (HIT3a; BD) and 5 ng/mL soluble anti-CD28 (CD28.2; BD) for 6 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 in the presence of brefeldin A (GolgiPlug; BD). After stimulation, cells were washed, stained with viability dye and antibodies to surface antigens, fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD), and stained intracellularly with fluorochrome-conjugated anti–interferon γ (IFN-γ; B27; BD). IFN-γ production after anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation and thrombin treatment was normalized to stimulated, untreated controls; a change in IFN-γ production (ΔIFN-γ) of 0 represents no effect of thrombin on a donor's IFN-γ response induced by anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation. A positive ΔIFN-γ represents percent enhancement, and a negative ΔIFN-γ represents percentage inhibition by thrombin. For identification of antigen specificity, PBMCs were incubated with major histocompatibility complex class I HLA-A*02–restricted tetramers loaded with CMV pp65 (NLVPMVATV) or influenza virus matrix protein 1 (GILGFVFTL) peptides (NIH Tetramer Facility) for 1 hour at room temperature prior to surface antibody staining.

Platelet Assays

Platelets were isolated as described previously [23]. In short, platelets were purified by gel filtration on a Sepharose 2B column (Sigma) and resuspended in HEPES-buffered Tyrode's solution (pH 7.4) with a final concentration of 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by stimulation with thrombin (α-Thrombin; Enzyme Research Labs) for 30 minutes at indicated concentrations. Expression of CD62P or TGF-β was determined by flow cytometry. Platelet culture supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C prior to analysis for TGF-β concentrations, using the human TGF-β1 Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Thrombin Activation of T Cells

Cultures of purified T cells, PBMCs, or purified T cells with added purified platelets were incubated with indicated concentrations of thrombin, TFLLR-NH2 (Tocris Bioscience), or vorapaxar (SCH 530348; AdooQ Bioscience). In other assays, PBMCs were incubated with 1 µg/mL anti–TGF-β1 (1D11; R&D Systems), 1 µg/mL mouse IgG1 isotype control (BD), or 1 µM LY2157299 (Cayman Chemical).

Statistics

We compared continuous variables by using the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn correction for multiple variables. Correlations were determined using a nonparametric Spearman test. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CX3CR1 Identifies a Population of Circulating Memory CD8+ T Cells

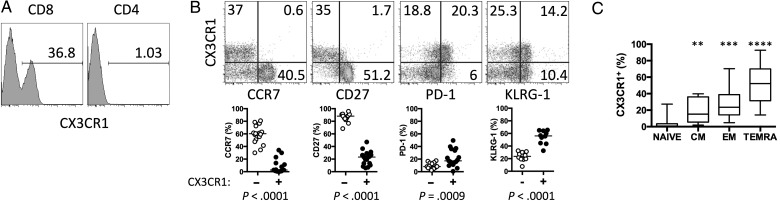

In healthy HIV-negative donors, a substantial proportion of circulating CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells express the fractalkine receptor, CX3CR1 (Figure 1A). Confirming and building on the findings of previous reports [24–26], we found that CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells do not readily express the lymph node–homing molecule CCR7 or the costimulatory molecule CD27 but do exhibit greater expression of the activation marker PD-1 and the NK-cell receptor KLRG-1, a marker of replicative history, than do CX3CR1neg CD8+ T cells (Figure 1B). Among T cells, CX3CR1 expression is restricted to memory CD8+ T cells, and its expression increases as memory CD8+ T cells mature, with the highest expression on CCR7negCD45RA+ TEMRA cells (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Circulating CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells are increased in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected antiretroviral therapy recipients. A, Surface CX3CR1 expression on CD8+ or CD4+ T cells from a representative HIV-uninfected donor (n = 17). B, CD8+ T-cell expression of CX3CR1 and CCR7, CD27, PD-1, or KLRG-1 in a representative HIV-uninfected donor (top). Percentage of CX3CR1− (open circles) or CX3CR1+ (closed circles) CD8+ T cells that express CCR7, CD27, PD-1, and KLRG-1 in HIV-uninfected donors (n = 7–16; bottom). P values were determined by the Mann–Whitney test. C, Percentage of naive (CD45RO−CCR7+), central memory (CM; CD45RO+CCR7+; **P = .0093), effector memory (EM; CD45RO+CCR7−; ***P = .001), and terminal effector memory RA (TEMRA; CD45RO−CCR7−; ****P < .001) CD8+ T cells that express surface CX3CR1. P values were calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparisons posttest.

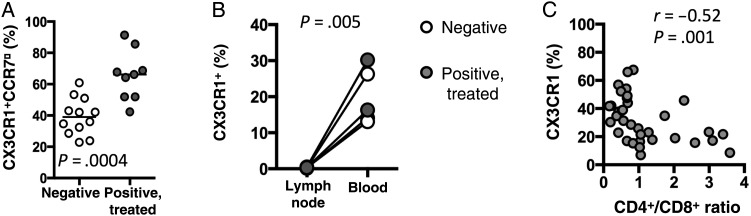

As CX3CR1+ cells characteristically express no or very low levels of CCR7, the majority of CD8+ T cells in circulation can be divided into one of 2 groups—CX3CR1+CCR7neg and CX3CR1negCCR7+. The percentage of CD8+ T cells that are CX3CR1+CCR7neg is significantly increased in HIV-infected ART recipients (Figure 2A). This increase was concomitant with a significant decrease in CX3CR1negCCR7+ CD8+ T-cell populations (data not shown). Consistent with a lack of biologically important levels of CCR7 expression, CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells are excluded from the lymph nodes in both HIV-infected subjects and healthy controls (Figure 2B). Importantly, CD8+ T-cell expression of CX3CR1 was strongly negatively correlated with CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio in HIV-infected ART recipients (Figure 2C), indicating that low CD4+/CD8+ ratios in HIV-infected ART recipients are associated with greater numbers of memory CD8+ T cells capable of localizing to vascular endothelium.

Figure 2.

A, Percentage of CD8+ T cells that are CX3CR1+CCR7− in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–uninfected donors (n = 12) and HIV-infected antiretroviral therapy (ART)–recipient donors (n = 9). The P value was determined by the Mann–Whitney test. B, Expression of CX3CR1 on CD8+ T cells from the lymph nodes or peripheral blood of HIV-uninfected donors (open circles; n = 2) or HIV-infected ART-recipient donors (filled circles; n = 3). The P value was determined by the paired t test. C, Correlation of CX3CR1 expression on CD8+ T cells and the ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected ART recipients (n = 35). P and r values were determined by Spearman correlation analysis.

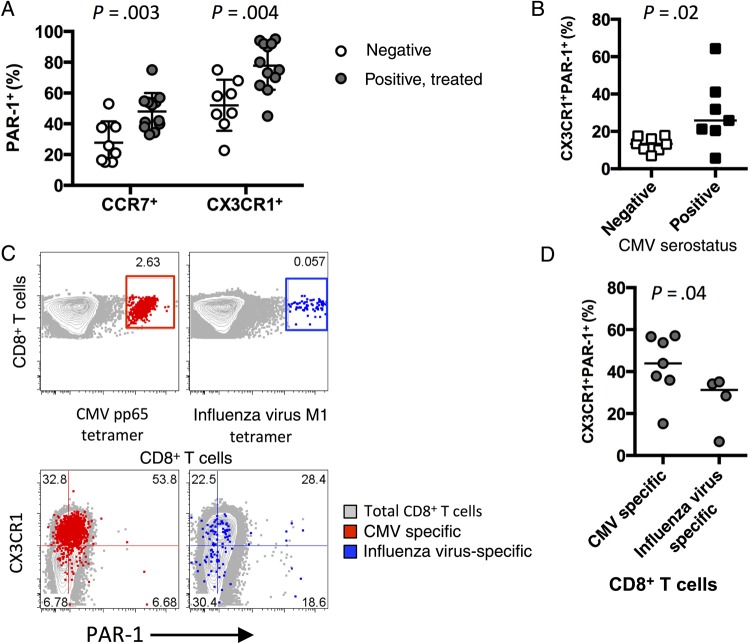

CX3CR1+ CD8+ T Cells Express the Thrombin Receptor PAR-1

Recent studies suggest a population of CD8+ T cells expressing the thrombin receptor PAR-1 can be activated by thrombin via PAR-1 ligation [20]. CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells are enriched for PAR-1 expression in both HIV-negative and HIV-infected individuals, and PAR-1 expression on both CX3CR1+ and CCR7+ CD8+ T-cell populations was increased in HIV-infected donors (Figure 3A). Most HIV-infected persons are coinfected with CMV [27, 28], and recent data from our group suggest that CMV coinfection drives robust expansion of circulating CD8+ T cells [7]. Accordingly, CMV coinfection is associated with an increase in the proportion of CX3CR1+PAR-1+ CD8+ T cells (Figure 3B). The extent to which the CD8+ T-cell expansion is composed of CMV-specific cells is unclear, although CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, but not cells specific for hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus, have been shown to express high levels of CX3CR1 [29]. Identification of circulating CD8+ T cells reactive to the immunodominant CMV protein pp65 revealed that the majority of these CMV-specific cells coexpressed CX3CR1 and PAR-1 in HIV-infected donors (Figure 3C and 3D). CX3CR1 and PAR-1 were coexpressed, but to a lesser extent, on influenza virus–specific CD8+ T cells (Figure 3C and 3D). These data and the sizable population of CX3CR1+PAR-1+ CD8+ T cells in CMV-negative HIV-infected individuals (Figure 3B) together suggest that this novel coexpression phenotype is a general outcome of CD8+ T-cell activation and differentiation in humans that is enhanced by CMV coinfection but not solely attributable to stimulation with CMV antigens.

Figure 3.

CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells express the thrombin receptor protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1). A, Percentage of CCR7+ or CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells that exhibit surface PAR-1 expression (n = 8). P values were determined by the Mann–Whitney test. B, Percentage of CD8+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected antiretroviral therapy (ART) recipients that coexpress CX3CR1 and PAR-1, by cytomegalovirus (CMV) seronegativity (n = 8) or seropositivity (n = 7). The P value was determined by the Mann–Whitney test. C, CD8+ expression and tetramer/peptide complex binding on CD8+ T cells (top). CMV pp65–specific cells (red) or influenza virus M1–specific (blue) cells are indicated. CX3CR1 and PAR-1 expression on total (gray), CMV pp65–specific (red), and influenza virus M1–specific (blue) CD8+ T cells (bottom). Numbers indicate the percentage of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in each quadrant (n = 4–7). D, Percentage of CD8+ T cells that coexpress CX3CR1 and PAR-1 from HIV-infected ART-recipient donors that are CMV pp65 specific (n = 7) or influenza virus M1 specific (n = 4). The P value was determined by the Mann–Whitney test.

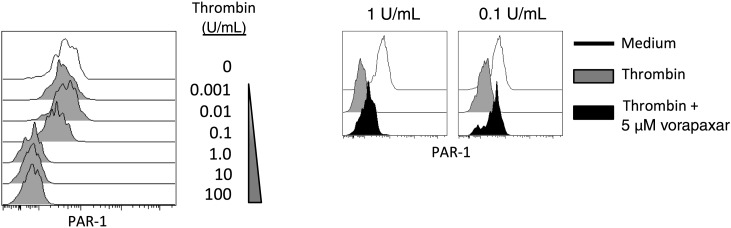

PAR-1 Activation Influences CD8+ T-Cell Function

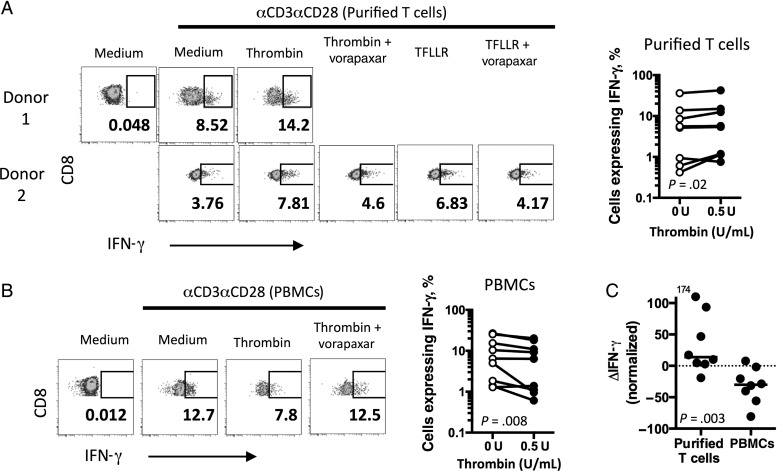

Activation of PAR-1 by thrombin involves the formation of a tethered peptide ligand from cleavage of an N-terminal portion of the receptor. Activated PAR-1 is then internalized via a clathrin-dependent pathway [30]. Stimulation of purified CD8+ T cells with thrombin induced PAR-1 internalization on CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells that could be partially blocked by the PAR-1 receptor antagonist vorapaxar (Figure 4). Thus, we confirm that thrombin can activate PAR-1 on CD8+ T cells. To test whether PAR-1 activation influences CD8+ T-cell function, we stimulated purified CD8+ T cells from healthy donors with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (αCD3/αCD28) in the presence of thrombin or the PAR-1 peptide agonist TFLLR (Figure 5A). Consistent with the findings of Catalfamo et al [20], there was a small but significant increase in the percentage of CCR7neg CD8+ T cells that exhibited IFN-γ production in the presence of thrombin (Figure 5A), and the enhancement could be blocked with vorapaxar. Surprisingly, when we repeated the stimulation experiments with unseparated PBMC preparations, we observed an opposite result. Rather than enhancing the proportion of cells with IFN-γ production, thrombin stimulation of PBMCs impaired the production of IFN-γ by CD8+ T cells (Figure 5B). These differences were most apparent when the thrombin-mediated change in IFN-γ expression was normalized to expression in the absence of thrombin (Figure 5C). Thus, PAR-1 activation on CD8+ T cells enhances effector function, yet this is masked by PAR-1 activation on a separate cell type found in blood, with a net inhibitory effect.

Figure 4.

Thrombin activation induces protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1) internalization. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were incubated with indicated concentrations of thrombin for 5 minutes and assayed by flow cytometry. Surface PAR-1 expression on CCR7neg CD8+ T cells (experiment representative of 2; left). Surface PAR-1 was determined following incubation with 5 µM vorapaxar for 20 minutes prior to thrombin activation (experiment representative of 2; right).

Figure 5.

Thrombin activation mediates CD8+ T-cell function. A, CD8+ and interferon γ (IFN-γ) expression on gated CCR7neg CD8+ T cells from 2 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–uninfected donors after stimulation of purified T cells for 6 hours in the presence of thrombin (0.5 U/mL), TFLLR (5 µM), or vorapaxar (5 µM), and anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (left). Percentage of CCR7neg CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ in purified T-cell cultures after 6 hours of stimulation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 in the absence (0 U/mL) or presence (0.5 U/mL) of thrombin (n = 8; right). The P value was determined by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. B, Left IFN-γ expression among CCR7neg CD8+ T cells from an HIV-uninfected donor after 6 hours of stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) treated as described in panel A (left). Percentage of CCR7neg CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ in PBMC cultures after stimulation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for 6 hours in the absence (0 U/mL) or presence (0.5 U/mL) of thrombin (n = 9; right). The P value was determined by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. C, Change in IFN-γ expression (ΔIFN-γ) after anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (αCD3αCD28) stimulation in the absence or presence (0.5 U/mL) of thrombin, normalized to total IFN-γ expression following stimulation without thrombin, as described in “Methods” section. The P value was calculated by the Mann–Whitney test).

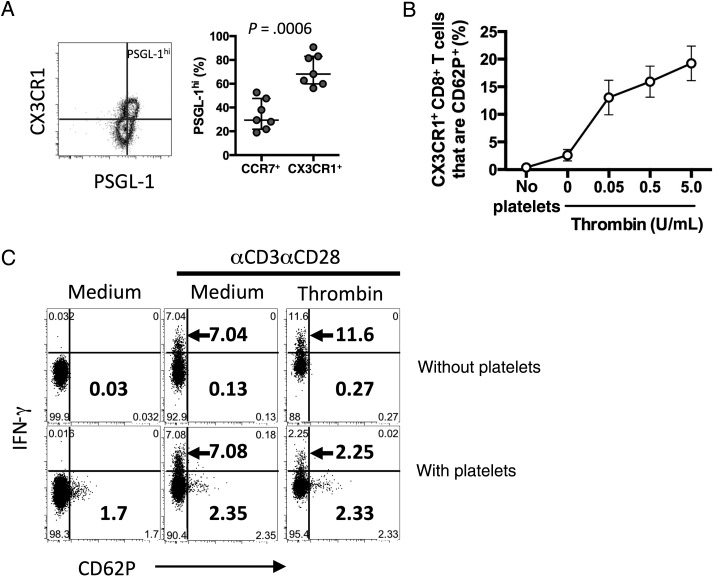

Platelets express high levels of PAR-1, have been shown to form conjugates with CD8+ T cells in HIV infection, and can release a variety of effector and regulatory molecules when stimulated with thrombin [31]. Activated platelets (which express CD62P/P-selectin) can interact with CD8+ T cells via CD62P binding with its receptor, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand (PSGL-1), which is expressed on all circulating CD8+ T cells and enriched in the CX3CR1+ CD8+ T-cell population (Figure 6A). CX3CR1+ CD8+ T-cell acquisition of CD62P, a measure of platelet binding, was enhanced by thrombin in vitro (Figure 6B). To determine whether thrombin-stimulated platelets could inhibit CD8+ T-cell function, we cultured purified T cells with gel-purified platelets from healthy donors and stimulated the culture with αCD3/αCD28 and thrombin. We measured intracellular IFN-γ and surface expression of CD62P, as evidence of platelet binding (Figure 6C). IFN-γ production by CCR7neg CD8+ T cells was reduced when platelets were present. Interestingly, the reduction in IFN-γ staining was greater than the percentage of CCR7neg CD8+ T cells that bound activated platelets, suggesting the possibility of an additional, soluble mechanism of platelet-mediated inhibition.

Figure 6.

Platelets bind to CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells. A, CX3CR1 and PSGL-1 expression on CD8+ T cells (left). Percentage of CCR7+ or CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells that are PSGL-1hi (n = 7; right). The P value was calculated by the Mann–Whitney test. B, Acquisition of CD62P (representative of platelet binding) to CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells in a purified T-cell/purified platelet coculture after thrombin stimulation (n = 6–8). C, Interferon γ (IFN-γ) expression and CD62P adhesion on CCR7neg CD8+ T cells after anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation in the presence or absence of gel-purified platelets (n = 8). Top numbers indicate the percentage of cells that are IFN-γ+/CD62Pneg, and bottom numbers indicate the percentage of cells that are IFN-γneg/CD62P+.

Platelet-Derived TGF-β Impairs CD8+ T-Cell Function

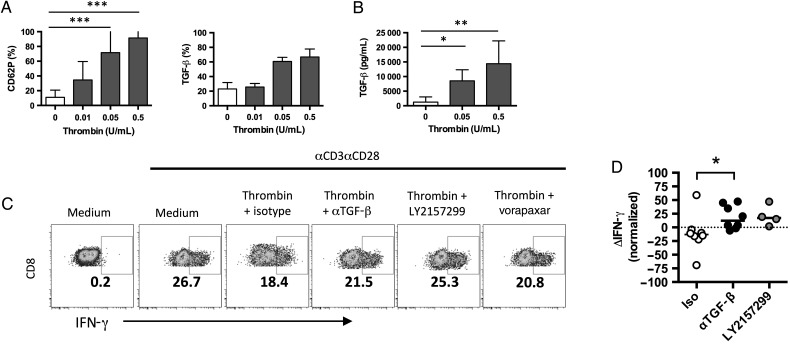

Platelets release many immunoregulatory molecules in response to activation stimuli [32], including components of the TGF-β complex [33–35]. TGF-β signaling is a recognized regulator of CD8+ T-cell function [36]. Thrombin exposure induced surface expression of CD62P and TGF-β on gel-purified platelets (Figure 7A). Thrombin-activated platelets also secreted soluble TGF-β1 (Figure 7B). In thrombin-activated PBMC cultures, neutralizing TGF-β activity with a monoclonal antibody or blocking TGF-β signaling with the small-molecule inhibitor LY2157299 restored the percentage of CCR7neg CD8+ T cells that produced IFN-γ (Figure 7C and 7D). Addition of vorapaxar to the culture prevented the thrombin-associated inhibition of T-cell function, consistent with a role for PAR-1 activity in the platelet-mediated inhibition. Therefore, our data suggest that there is a complex interaction in the nascent clot, wherein newly formed thrombin can either directly enhance CD8+ T-cell expression of IFN-γ or, by activating platelets, induce expression of TGF-β that negatively modulates T-cell inflammation to potentially inhibit clot immunopathology.

Figure 7.

Activated platelets modulate CD8+ T-cell function via transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) release. A, Expression of CD62P (left) or TGF-β (right) on the surface of gel-purified platelets after thrombin activation (n = 3–13). ***P < .001, by the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparisons posttest. B, Quantification of TGF-β protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in supernatants of thrombin-activated platelets (n = 5). *P = .0474 and **P = .0047, by the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparisons posttest. C, CD8+ and interferon γ (IFN-γ) expression by CCR7neg CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures treated with 0.5 U/mL thrombin and mouse immunoglobulin G1 (isotype), anti–TGF-β, LY2157299, or vorapaxar. D, Change in IFN-γ expression (ΔIFN-γ) after anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (αCD3αCD28) stimulation (0.5 U/mL vs 0 U/mL thrombin), normalized to total IFN-γ expression following stimulation without thrombin, as described in “Methods” section. *P = .0481, by the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparisons posttest.

DISCUSSION

Although we did not observe significant expansion of CD8+ T cells in this study (data not shown), in general, expansion of the CD8+ T-cell pool occurs early in HIV infection, and in most persons CD8+ T-cell numbers remain expanded despite years of suppressive ART [3]. CD8+ T-cell expansion and the resultant inversion of the CD4+/CD8+ ratio in ART recipients predict morbid events, but the determinants of this risk are not understood [3–5]. The association between abnormal CD8+ T-cell expansion and morbid outcomes is also apparent in the HIV-uninfected elderly population, yet here, too, the mechanisms underlying these risks are unclear [37]. As some of these morbidities are cardiovascular related, we sought to examine the mechanisms whereby CD8+ T-cell lymphocytosis in ART recipients might contribute to CVD risk and how CD8+ T cells interact with other immune cell types involved in atherosclerosis and thrombosis.

Specific patterns of chemokine receptor expression help dictate the tissue tropism of T cells. The CCR7 chemokine receptor identifies T cells that can home to lymphoid tissues, whereas the CX3CR1 chemokine receptor is important for tissue-bound effector T-cell rolling and adhesion along vascular endothelium [38]. We found that, in healthy controls and HIV-infected ART recipients, circulating CD8+ T cells expressed either CX3CR1 or the lymph node–homing receptor CCR7 exclusively and only rarely expressed both. Proportions of CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells were significantly higher in ART recipients than in uninfected controls, suggesting that the expanded CD8+ T cells that persist in ART recipients are capable of preferentially localizing to vascular endothelium. Whether these circulating CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells represent precursors of a vascular tissue-resident population remains to be seen. CX3CR1 is likely important in atherogenesis, as its expression is highly prevalent in human atherosclerotic lesions, and certain polymorphisms in CX3CR1 can be atheroprotective [11, 12]. CX3CR1 expression on CD8+ T cells is also linked to cytolytic activity [25, 29]. These findings raise the possibility that expansion and persistence of CX3CR1-expressing CD8+ T cells that localize to vascular endothelium may predispose HIV-infected persons to cardiovascular risk.

Indices of inflammation and coagulation are heightened in ART-suppressed HIV-infected persons, particularly in patients with suboptimal CD4+ T-cell reconstitution [39, 40], and these indices predict cardiovascular risk [41, 42]. Circulating immune cells can interact with soluble coagulation elements through expression of the thrombin receptor PAR-1. A recent report found increased surface PAR-1 expression on CD8+ T cells in viremic HIV-infected patients but not patients receiving ART [20]. Here we show that even among aviremic HIV-infected persons, PAR-1 surface expression is increased on all CD8+ T cells and is particularly elevated on CD8+ T cells expressing CX3CR1. PAR-1 may be important for CD8+ T cells to directly sense and respond to coagulation factors, particularly among CD8+ T cells that are CMV specific, as CMV can infect endothelial cells that can promote coagulation [43].

The effects of PAR-1 activation have been examined in innate immune cells; for instance, exposure of dendritic cells to thrombin induces secretion of interleukin 1β [44], and in mice, deletion of PAR-1 attenuates the innate immune response to influenza virus infection [45]. Less is known about the effects of PAR-1 activation on adaptive immune cells. We found that treatment with thrombin induces dose-dependent PAR-1 internalization in CD8+ T cells and confirmed an earlier report that thrombin augments IFN-γ production in purified CD8+ T cells in vitro [20]. This effect was also seen with the PAR-1 agonist TFLLR and could be blocked in both cases with the PAR-1 antagonist vorapaxar. These results are consistent with a proinflammatory effect of PAR-1 activation.

While purified CD8+ T cells can respond to thrombin in vitro, a more physiological scenario of thrombin exposure in vivo might occur in blood, where platelets, monocytes, and other circulating immune cells are present at the site of clot formation. Accordingly, we found that, in whole PBMC preparations, thrombin inhibits the proportion of CD8+ T cells that produce IFN-γ that, in culture, is dependent on the presence of platelets. The inhibitory effect on CD8+ T cells is mediated at least in part through thrombin-induced TGF-β secretion by platelets, indicating an additional antiinflammatory effect of thrombin. While it is not likely that circulating CD8+ T cells would interact with thrombin in the absence of platelets, CD8+ T-cell activation by thrombin without attenuation by platelets might occur in the central nervous system, where thrombin has been shown to regulate a number of cellular processes in neurons and astrocytes [46, 47].

PSGL-1 on circulating leukocytes can mediate adhesive interactions with activated platelets via binding to CD62P. We assessed PSGL-1 expression on circulating CD8+ T cells and found that all CD8+ T cells express PSGL-1, with higher surface densities found on cells that express CX3CR1. Furthermore, CX3CR1+ CD8+ T cells were able to form complexes with activated platelets in the presence of thrombin. Higher frequencies of circulating CD8+ T-cell–platelet conjugates have been found in fresh blood samples obtained from ART recipients [14]. Notably, it is unlikely that platelets exert a substantial effect on CD8+ T cells globally, as only a small fraction of CD8+ T cells are found to be complexed with platelets in circulation, and it is unknown how stable these interactions are in vivo. Moreover, the biological significance of these interactions in vivo is unclear, as the magnitude of platelet-mediated inhibition on CD8+ T-cell function that we observed is quite modest. However, given that plasma levels of the coagulation marker D-dimer correlate with frequencies of circulating CD8+ T-cell–platelet conjugates in HIV-infected ART recipients [14], it is conceivable that coagulation can influence these interactions, which, in turn, could affect CD8+ T-cell function in some meaningful way. Local effects of CD8+ T-cell–platelet complexes may be particularly important at sites of vascular inflammation and injury, where cross-talk with platelets could limit CD8+ T-cell effector function and regulate inflammation at the site of clot formation.

Our data suggest that the CX3CR1+PAR-1+ phenotype is a general consequence of T-cell maturation and activation and that, in the setting of ART-treated HIV infection, these cells are in the right place at the wrong time and can contribute to CVD. Indeed, CD8+ T-cell activation is linked to the presence of carotid plaque in treated HIV infection [48]. In-depth phenotyping of leukocyte populations within human arterial plaques has shown that the plaque represents an immunologic compartment that is distinct from peripheral blood, with high frequencies of CD8+ T cells that are preferentially activated [49]. While further studies are needed to assess the direct role of CD8+ T cells in atherosclerotic plaque development and thrombosis, it is likely that expression of CX3CR1 on CD8+ T cells plays a role in localization to these sites. Our findings of skewed proportions of CD8+ T cells that express CX3CR1 and their propensity to interact with thrombin, a mediator of thrombosis, may implicate a role for these cells in CVD risk in HIV infection.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Sulggi Lee and Peter Hunt (University of California, San Francisco) and Irini Sereti (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) for helpful discussions.

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIH (grants T32AI089474 [to J. C. M.], R56HL126563 [to N. T. F.], and P01AI076174 and UM1AI069501 [to M. M. L.]), the Richard J. Fasenmyer Foundation, and the Center for AIDS Research at Case Western Reserve University (grant P30AI036219; developmental awards to D. A. Z. and M. L. F.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Mudd JC, Lederman MM. CD8 T cell persistence in treated HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014; 9:500–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serrano-Villar S, Gutierrez C, Vallejo A et al. The CD4/CD8 ratio in HIV-infected subjects is independently associated with T-cell activation despite long-term viral suppression. J Infect 2013; 66:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano-Villar S, Sainz T, Lee SA et al. HIV-infected individuals with low CD4/CD8 ratio despite effective antiretroviral therapy exhibit altered T cell subsets, heightened CD8+ T cell activation, and increased risk of non-AIDS morbidity and mortality. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serrano-Villar S, Perez-Elias MJ, Dronda F et al. Increased risk of serious non-AIDS-related events in HIV-infected subjects on antiretroviral therapy associated with a low CD4/CD8 ratio. PLoS One 2014; 9:e85798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castilho JL, Shepherd BE, Koethe J et al. CD4+/CD8+ ratio, age, and risk of serious noncommunicable diseases in HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2016; 30:899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Sinclair E et al. Increased carotid intima-media thickness in HIV patients is associated with increased cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell responses. AIDS 2006; 20:2275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman ML, Mudd JC, Shive CL et al. CD8 T-cell expansion and inflammation linked to CMV coinfection in ART-treated HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:392–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apostolakis S, Spandidos D. Chemokines and atherosclerosis: focus on the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013; 34:1251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damas JK, Boullier A, Waehre T et al. Expression of fractalkine (CX3CL1) and its receptor, CX3CR1, is elevated in coronary artery disease and is reduced during statin therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25:2567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin MS, You S, Kang Y et al. DNA methylation regulates the differential expression of CX3CR1 on human IL-7Ralphalow and IL-7Ralphahigh effector memory CD8+ T cells with distinct migratory capacities to the fractalkine. J Immunol 2015; 195:2861–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott DH, Halcox JP, Schenke WH et al. Association between polymorphism in the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 and coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2001; 89:401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moatti D, Faure S, Fumeron F et al. Polymorphism in the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 as a genetic risk factor for coronary artery disease. Blood 2001; 97:1925–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panigrahi S, Freeman ML, Funderburg NT et al. SIV/SHIV infection triggers vascular inflammation, diminished expression of Kruppel-like factor 2 and endothelial dysfunction. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green SA, Smith M, Hasley RB et al. Activated platelet-T-cell conjugates in peripheral blood of patients with HIV infection: coupling coagulation/inflammation and T cells. AIDS 2015; 29:1297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding SA, Sommerfield AJ, Sarma J et al. Increased CD40 ligand and platelet-monocyte aggregates in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis 2004; 176:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph JE, Harrison P, Mackie IJ, Isenberg DA, Machin SJ. Increased circulating platelet-leucocyte complexes and platelet activation in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Haematol 2001; 115:451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarma J, Laan CA, Alam S, Jha A, Fox KA, Dransfield I. Increased platelet binding to circulating monocytes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2002; 105:2166–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson CM, Nemerson Y. Blood coagulation. Annu Rev Biochem 1980; 49:765–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coughlin SR. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature 2000; 407:258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurley A, Smith M, Karpova T et al. Enhanced effector function of CD8(+) T cells from healthy controls and HIV-infected patients occurs through thrombin activation of protease-activated receptor 1. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:638–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colognato R, Slupsky JR, Jendrach M, Burysek L, Syrovets T, Simmet T. Differential expression and regulation of protease-activated receptors in human peripheral monocytes and monocyte-derived antigen-presenting cells. Blood 2003; 102:2645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien PJ, Prevost N, Molino M et al. Thrombin responses in human endothelial cells. Contributions from receptors other than PAR1 include the transactivation of PAR2 by thrombin-cleaved PAR1. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:13502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podrez EA, Byzova TV, Febbraio M et al. Platelet CD36 links hyperlipidemia, oxidant stress and a prothrombotic phenotype. Nat Med 2007; 13:1086–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combadiere B, Faure S, Autran B, Debre P, Combadiere C. The chemokine receptor CX3CR1 controls homing and anti-viral potencies of CD8 effector-memory T lymphocytes in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2003; 17:1279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura M, Umehara H, Nakayama T et al. Dual functions of fractalkine/CX3C ligand 1 in trafficking of perforin+/granzyme B+ cytotoxic effector lymphocytes that are defined by CX3CR1 expression. J Immunol 2002; 168:6173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Priol Y, Puthier D, Lecureuil C et al. High cytotoxic and specific migratory potencies of senescent CD8+ CD57+ cells in HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. J Immunol 2006; 177:5145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robain M, Carre N, Dussaix E, Salmon-Ceron D, Meyer L. Incidence and sexual risk factors of cytomegalovirus seroconversion in HIV-infected subjects. The SEROCO Study Group. Sex Transm Dis 1998; 25:476–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gianella S, Massanella M, Wertheim JO, Smith DM. The sordid affair between human herpesvirus and HIV. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:845–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bottcher JP, Beyer M, Meissner F et al. Functional classification of memory CD8(+) T cells by CX3CR1 expression. Nat Commun 2015; 6:8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soh UJ, Dores MR, Chen B, Trejo J. Signal transduction by protease-activated receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 160:191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coppinger JA, Cagney G, Toomey S et al. Characterization of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to localization of novel platelet proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions. Blood 2004; 103:2096–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr, Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:264–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assoian RK, Sporn MB. Type beta transforming growth factor in human platelets: release during platelet degranulation and action on vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol 1986; 102:1217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wassmer SC, de Souza JB, Frere C, Candal FJ, Juhan-Vague I, Grau GE. TGF-beta1 released from activated platelets can induce TNF-stimulated human brain endothelium apoptosis: a new mechanism for microvascular lesion during cerebral malaria. J Immunol 2006; 176:1180–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grainger DJ, Wakefield L, Bethell HW, Farndale RW, Metcalfe JC. Release and activation of platelet latent TGF-beta in blood clots during dissolution with plasmin. Nat Med 1995; 1:932–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AK, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2006; 24:99–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadrup SR, Strindhall J, Kollgaard T et al. Longitudinal studies of clonally expanded CD8 T cells reveal a repertoire shrinkage predicting mortality and an increased number of dysfunctional cytomegalovirus-specific T cells in the very elderly. J Immunol 2006; 176:2645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fong AM, Robinson LA, Steeber DA et al. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 mediate a novel mechanism of leukocyte capture, firm adhesion, and activation under physiologic flow. J Exp Med 1998; 188:1413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lederman MM, Calabrese L, Funderburg NT et al. Immunologic failure despite suppressive antiretroviral therapy is related to activation and turnover of memory CD4 cells. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:1217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lederman MM, Funderburg NT, Sekaly RP, Klatt NR, Hunt PW. Residual immune dysregulation syndrome in treated HIV infection. Adv Immunol 2013; 119:51–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunt PW, Sinclair E, Rodriguez B et al. Gut epithelial barrier dysfunction and innate immune activation predict mortality in treated HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1228–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenorio AR, Zheng Y, Bosch RJ et al. Soluble markers of inflammation and coagulation but not T-cell activation predict non-AIDS-defining morbid events during suppressive antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1248–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Squizzato A, Gerdes VE, Buller HR. Effects of human cytomegalovirus infection on the coagulation system. Thromb Haemost 2005; 93:403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niessen F, Schaffner F, Furlan-Freguia C et al. Dendritic cell PAR1-S1P3 signalling couples coagulation and inflammation. Nature 2008; 452:654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khoufache K, Berri F, Nacken W et al. PAR1 contributes to influenza A virus pathogenicity in mice. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:206–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaughan PJ, Pike CJ, Cotman CW, Cunningham DD. Thrombin receptor activation protects neurons and astrocytes from cell death produced by environmental insults. J Neurosci 1995; 15:5389–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Ubl JJ, Stricker R, Reiser G. Thrombin (PAR-1)-induced proliferation in astrocytes via MAPK involves multiple signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2002; 283:C1351–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longenecker CT, Funderburg NT, Jiang Y et al. Markers of inflammation and CD8 T-cell activation, but not monocyte activation, are associated with subclinical carotid artery disease in HIV-infected individuals. HIV Med 2013; 14:385–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grivel JC, Ivanova O, Pinegina N et al. Activation of T lymphocytes in atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31:2929–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]