Abstract

Posttranslational modifications add diversity to protein function. Throughout its life cycle, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) undergoes numerous covalent posttranslational modifications (PTMs), including glycosylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, phosphorylation, and palmitoylation. These modifications regulate key steps during protein biogenesis, such as protein folding, trafficking, stability, function, and association with protein partners and therefore may serve as targets for therapeutic manipulation. More generally, an improved understanding of molecular mechanisms that underlie CFTR PTMs may suggest novel treatment strategies for CF and perhaps other protein conformational diseases. This review provides a comprehensive summary of co- and posttranslational CFTR modifications and their significance with regard to protein biogenesis.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, protein trafficking, glycosylation, ubiquitination, phosphorylation, palmitoylation

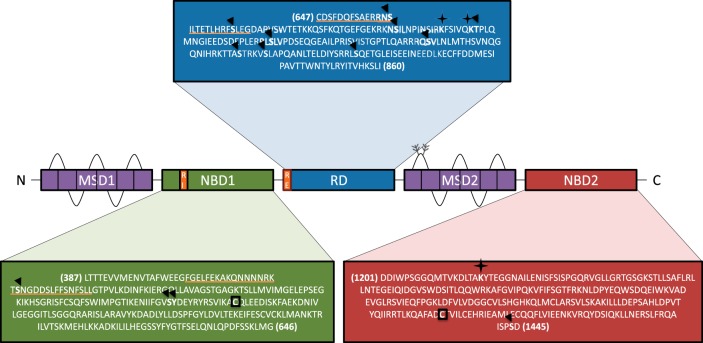

cystic fibrosis (cf), a disease caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR; also known as ABCC7), affects ∼70,000 individuals worldwide (http://www.cff.org). The disease alters secretion within exocrine tissues such as the lung, pancreas, intestines, sweat glands, and vas deferens. CFTR functions as an ion channel that transports chloride and bicarbonate across the apical surfaces of epithelia and is also expressed in other cell types. In airways and respiratory submucosal glands, defective CFTR leads to a viscous secretion that becomes progressively difficult to clear and predisposes patients to infection by pathogenic bacteria. CFTR includes two membrane spanning domains (MSD1, MSD2), each containing six transmembrane helices that are separated in the CFTR primary amino acid sequence by a nucleotide binding domain (NBD1) and a structurally disordered regulatory domain (RD). Downstream of MSD2 is a second nucleotide binding domain (NBD2) and a cytoplasmic COOH-terminal region encoding a PDZ-binding motif (Fig. 1). To date, over 1,900 mutations have been identified in CFTR (http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca; http://www.cftr2.org), many of which are known to cause disease (52, 107, 145, 153, 155, 165).

Fig. 1.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) structural domains. The schematic illustrates the five key structural domains of CFTR. The two membrane spanning domains (MSD1, MSD2), shown in purple, each contain six transmembrane helices. Downstream of MSD1 is the first nucleotide binding domain (NBD1, shown in green), which includes the regulatory insertion (RI, orange underline). This is followed by a structurally disordered regulatory domain (RD, shown in blue), which includes the regulatory extension (RE, orange underline) that interacts with NBD1. Downstream of MSD2 is a second nucleotide binding domain (NBD2, shown in red) and a cytoplasmic COOH-terminal region. Approximate boundaries are derived from recently available information. Examples of residues that are phosphorylated are denoted with an arrowhead, those that are modified with ubiquitin are designated with a star, and those that are palmitoylated are boxed.

Wild-type CFTR is synthesized and then assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), processed and sorted in the Golgi apparatus, and trafficked to the plasma membrane. From there, CFTR is internalized to early endosomes and either recycled to the cell surface or targeted for lysosomal degradation (11). Mutant CFTRs are traditionally grouped into six categories: class I: defective protein synthesis (e.g., G542X, R1162X); class II: defective protein maturation leading to premature degradation (e.g., F508del, N1303K, G85E, and E92K); class III: defective channel regulation (e.g., G551D); class IV: defective conductance or channel gating (e.g., R117H, R347P); class V: decreased levels of protein synthesis; and class VI: faulty recycling or increased internalization from the cell surface (58, 189, 208).

The most common disease-associated mutation among Caucasians is deletion of phenylalanine 508 (F508del), a class II defect, which results in a misfolded protein that is prematurely destroyed via endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) (38, 77, 188, 192). This particular mutation is present in at least one allele for ∼ 87% of CF patients in the United States (Patient Registry: 2011 Annual Data Report to the Center Directors, Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation 2012). In the event F508del CFTR is able to escape ERAD, the protein exhibits a diminished half-life due to an accelerated endocytic rate and reduced ion transport activity (67); therefore, bypassing ERAD is not sufficient to fully rescue disease-associated phenotypes. Of the remaining mutations, only four (G542X, G551D, W1282X, and N1303K) are present in >1% of CF patients in the United States. Among these, the class II G551D allele occurs on at least one chromosome for ∼4.4% of individuals with CF (Patient Registry: 2011 Annual Data Report to the Center Directors, Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation 2012). The G551D missense mutation results in a protein product that traffics normally to the plasma membrane but has markedly defective ion channel activity (50, 180, 196). A small molecule therapeutic, ivacaftor (Kalydeco), recently approved by the FDA, improves G551D CFTR channel activity and has shown substantial benefit among patients harboring this mutation (3, 79, 180). Other, more rare disease alleles that similarly exhibit defective channel gating are also amenable to treatment with “potentiators” such as ivacaftor (181). Significant focus in CF research is now being applied towards identifying small molecules that improve processing and function of other mutations, particularly F508del. Both academic and industrial efforts have led to the isolation of numerous F508del CFTR “correctors” (26, 107, 154, 184). However, the level of rescue in vivo using first generation corrector compounds in patients has not been robust, and other drugs will likely be needed for more complete repair of F508del CFTR biogenesis. One such corrector, lumacaftor, confers moderate improvement in patients when administered in combination with ivacaftor. Orkambi, a drug containing both lumacaftor and ivacaftor, has been approved in the United States for treatment of F508del homozygous individuals (26).

From the time it is synthesized until the point it is degraded, CFTR undergoes numerous covalent posttranslational modifications (PTMs), including glycosylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, phosphorylation, and palmitoylation. Modifications such as these are critical regulators of protein folding, trafficking, and function and therefore may serve as targets for therapeutic manipulation. To better rescue mutant forms of CFTR, we need to understand the impact of PTMs on biogenesis and function. This review provides a comprehensive summary of co- and posttranslational CFTR modifications and their significance in this regard.

Glycosylation

Processing of glycoproteins in the ER.

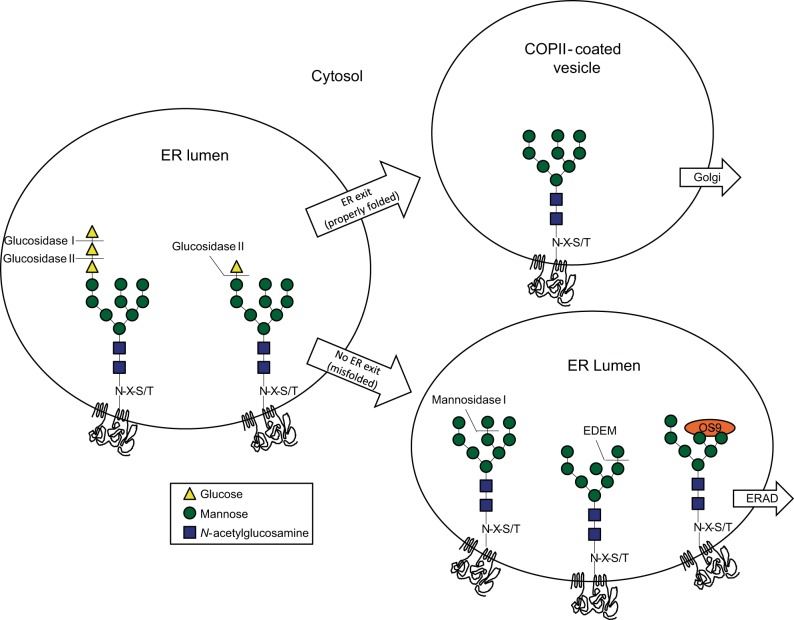

As noted above, covalent modifications provide diverse signals that regulate protein folding, function, stability, and association with specific binding partners. These modifications also furnish signals for trafficking through various subcellular compartments. Co- and posttranslational glycosylation generates exceedingly complex signaling codes by attaching and trimming between 1–200 distinct sugars on a single protein. N-glycosylation is a particularly well-studied regulator of protein folding (4, 168). Co-translational attachment of a core oligosaccharide (composed of 3 glucose, 9 mannose, and 2 N-acetylglucosamine residues; Glc3Man9GlcNAc2; see Fig. 2) en bloc to an asparagine within an N-X-S/T motif in a target protein is performed by the oligosaccharyltransferase. This enzyme is ideally situated to perform this function as it resides in complex with the Sec61 protein translocation (import) channel, which in turn is associated with the ribosome (36, 69, 80). For CFTR, the core glycans are attached on two residues (N894 and N900) in extracellular loop 4 of MSD2. Following Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 attachment, trimming of glucose and mannose residues may help determine whether a glycoprotein, such as CFTR, will undergo additional folding cycles or become routed to ERAD.

Fig. 2.

Processing of N-glycans on nascent secreted proteins such as CFTR. Core glycan attachment occurs cotranslationally on 2 residues in CFTR (N894 and N900). Further processing by glucosidases regulates CFTR folding cycles and exit from the for endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Additional mannose trimming can direct misfolded proteins for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) (see text).

In the typical glycan trimming pathway, removal of the outermost glucose by glucosidase I (resulting in a diglucosylated oligosaccharide) prevents further interaction with oligosaccharyltransferase. The remaining 2 glucose residues can then be removed by glucosidase II. The initial trimming by glucosidase II results in a monoglucosylated (Glc1Man9GlcNAc2) oligosaccharide, a signal that promotes protein folding mediated by advancement of glycoproteins to the calnexin/calreticulin cycle (28, 46, 62, 66, 146, 159). Of the two lectin-like ER chaperones, calnexin in particular seems to play a key role during CFTR folding (see below). The second trimming step by glucosidase II (Man9GlcNAc2) allows nascent proteins to exit the ER (Fig. 2). While properly folded polypeptides enter coatamer protein II (COPII)-coated vesicles, misfolded proteins (e.g., F508del CFTR) are selectively processed by mannosidase I (to Man8GlcNAc2) and a member of the ER degradation enhancing alpha-mannosidase-like protein family, or EDEM (72, 128, 135, 136, 171). Following conversion to shorter mannose-containing chains, which decreases the affinity between the nascent glycoprotein and calnexin/calreticulin, OS-9 (osteosarcoma 9) directs misfolded glycoproteins to ERAD (142). Interestingly, some of these events may occur in a subregion of the ER or even outside of the ER compartment in vesicles that lack ERGIC53 (ER-Golgi intermediate compartment protein 53) or the COPII vesicular protein Sec23 (22, 99, 141, 209).

Glycan-directed processing of CFTR in the ER.

Studies of protease susceptibility, thermoaggregation, and ubiquitination have identified an important role for glycosylation with regard to the stability of CFTR but not necessarily function or targeting to the cell surface (55). Multiple reports have demonstrated that wild-type and F508del CFTR enter the calnexin/calreticulin folding cycle where they directly bind calnexin (32, 55, 138, 139, 146). Knockdown of calnexin (e.g., with siRNA) or expression of unglycosylated CFTR (N894D/N900D; incapable of becoming glycosylated and thus binding calnexin) indicates that functional wild-type CFTR is able to traffic towards the cell surface (although at reduced levels) in the absence of calnexin binding; however, the protein may be less stable. Unglycosylated F508del CFTR, on the other hand, is unable to escape quality control and remains sequestered in the ER (32, 55). More in-depth studies of CFTR folding have suggested that calnexin binding is essential for achieving the proper conformation of CFTR subdomains, including the MSDs, which appear to be stabilized by the calnexin/calreticulin binding process (150).

Trafficking of CFTR to the Golgi and complex glycan attachment.

The vesicle coat protein Sec24 mediates CFTR exit from the ER via COPII-coated vesicles, likely through recognition of a diacidic exit code in NBD1 (140, 186). Recent reports suggest that many peptides are sorted in the ERGIC (ER-Golgi intermediate compartment), a check point from which properly folded proteins progress to the Golgi while others are recycled to the ER by retrograde transport in COPI-coated vesicles (13, 94, 147). Entrance into ERGIC is largely dependent on glycan attachment. As such, ERGIC-53, a key shuttling protein for this pathway, preferentially binds to high mannose oligosaccharides (83). Both wild-type and F508del CFTR are present in the ERGIC, although only wild-type CFTR advances to the cell surface (54). These data are consistent with the notion that ERGIC or the ER-derived “vesicular tubular cluster” plays a critical role as a quality control checkpoint (125).

In the Golgi apparatus, complex glycan attachment by 1 of more than 200 glycosyltransferases further regulates protein biogenesis (95). Specifically, within the cis-Golgi, N-glycoproteins such as CFTR are generally characterized by high mannosylation (8–9 residues). Trimming by α-mannosidases (resulting in Man5GlcNAc2) allows entrance into the medial-Golgi, where GlcNAc transferase-I (GlcNAcT-I) initiates complex glycan attachment (182). The attachment of additional sugars requires trimming to three mannose residues and addition of a second GlcNAc. In subsequent steps, complex arrangements of sugars such as GlcNAc, Gal (galactose), GalNAc (N-acetylgalactosamine), and Fuc (fucose) are assembled (151).

Trafficking and stability of CFTR in post-ER compartments.

While the precise sequence of events during CFTR oligosaccharide formation is unknown, and the specific modifications on CFTR are not completely clear (also see below), sensitivity to N-glycanase and endo-β-galactosidase, the Datura stramonium agglutination (DSA)-lectin binding characteristics, and the electrophoretic mobility shift detected by fast activated cell-based ELISA (i.e., FACE) suggest that CFTR contains repeating units of N-acetyllactosamine, which may recruit glycan-binding proteins (134). Core glycosylation is associated with stable folding of CFTR in the ER; however, neither core nor complex glycans appear to be required to achieve the correctly folded state. Glycosylation also appears to serve a role in stabilizing CFTR in the plasma membrane by influencing rates of protein endocytosis (32, 40). Under certain conditions, and in some cell types, CFTR may bypass the Golgi altogether, thereby avoiding complex glycosylation (18, 199). In this case, the protein may traffic to the cell surface via an unconventional Golgi reassembly stacking protein (GRASP)-dependent secretory pathway (53). Not only is core-glycosylated wild-type CFTR directed to the cell surface in this manner functional, but F508del CFTR can also be routed to the cell surface by a GRASP-dependent mechanism. F508del homozygous mice expressing a transgenic GRASP55 (TgGRASP55) showed increased mutant CFTR expression and short circuit current (Isc), as well as overall increased growth and survival rates, compared with TgGRASP55-null F508del animals (53). Alternative CFTR trafficking pathways such as GRASP represent potential modes of therapeutic intervention and may comprise sites of action for some of the CFTR corrector molecules recently discovered via high throughput compound library screening.

Glycan-deficient CFTR (N894D/N900D) exhibits an increased turnover rate and recycling to the apical surface from endosomes is significantly diminished. Additionally, immunofluorescence and pH-based fluorescence ratiometric image analysis shows accumulation of N894D/N900D CFTR in lysosomes, whereas wild-type CFTR internalizes more prominently within recycling endosomes (55). Nevertheless, glycan attachment at N894 (vs. N900) appears to serve a distinct function. Maturation of N894D CFTR is similar to that of the wild-type protein, whereas N900D matures less efficiently and turns over more rapidly. These data suggest that N900 is dominant for efficient trafficking to the plasma membrane. Blocking ER-to-Golgi transport with brefeldin A also indicates the importance of N900 as a mediator of CFTR routing to the proteosome via ERAD (32).

Deciphering the glycocode of proteins such as CFTR represents an important and topical area of research. Multiple mass spectrometric methods have been developed to assist mapping of glycan attachment for specific proteins (100, 194). While the capability of certain methods are limited at present, improvements in instrument sensitivity, together with computational and algorithm advancement, have been robust and continue to advance. Determining the complex glycan structure that characterizes CFTR at various stages of biogenesis (e.g., in post-Golgi compartments) is likely to provide valuable information regarding at least some of the mechanisms that govern the fate of CFTR, the extent to which pharmacologic rescue of F508del confers a “wild-type” protein configuration, and possibly new targets for therapeutic intervention in the disease.

Ubiquitination

Ubiquitin conjugation on CFTR.

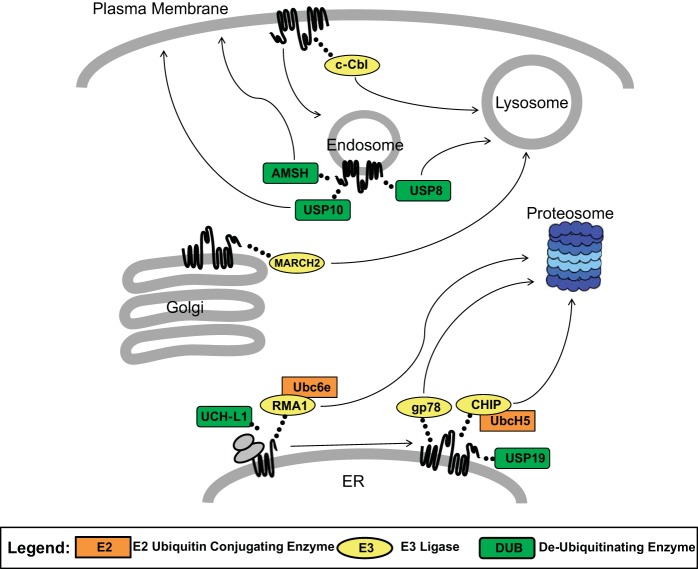

Ubiquitination is a multifaceted co- and posttranslational modification capable of regulating intermolecular binding interactions, protein stability, subcellular localization, endosomal sorting, recycling, and degradation. In general, conformationally destabilized CFTR, such as F508del CFTR or immature wild-type CFTR, exhibits elevated levels of ubiquitination. This modification augments routing towards proteosomal degradation (for ER localized CFTR) and enhances internalization from the cell surface with subsequent processing from early endosomes to the lysosome (137, 161). Ubiquitin attachment alters protein surface topology and is regulated by numerous ligases, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), and chaperones. Three well-described classes of enzymes, the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, are required for attachment of ubiquitin to ε-amino groups of lysine residues on target proteins (48). Ubiquitin is assembled on the E1 ligase, followed by transfer to an E2 for protein conjugation. E3 enzymes recruit specific E2/substrate complexes, which result in ubiquitin addition on the target protein. Therefore, the E3 ligase provides specificity, and upwards of 500 E3 ligases may be present in the human genome. In contrast, only two E1 ubiquitin activating enzymes and ∼30 E2 ligases are encoded in human DNA (132). As a result, specific E3 enzymes are viewed as crucial determinants that control the maturation and fate of ubiquitinated proteins such as CFTR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Factors involved in CFTR ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Processing of CFTR is governed by numerous ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), as well as chaperones and cochaperones (not shown). Ubiquitin attachments not only direct misfolded protein from the ER to the proteosome but also mediate recycling of CFTR to the cell surface and target unstable protein from the cell surface and early endosome towards degradation. The ligases and DUBs shown here represent select mediators of CFTR ubiquitination; however, the full ubiquitin/quality control network is much more complex with new key enzymes continually being characterized.

Protein complexes mediate CFTR ubiquitination and processing.

In addition to ubiquitin ligases, the maturation of nascent proteins in the ER is governed by interactions with numerous chaperones and cochaperones. Heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 and 90, for example, are necessary for proper recognition of CFTR folding configurations, as determined using both human and other cell systems (74, 119, 129, 137, 157, 197, 200, 201, 204). During cotranslational CFTR folding, Hsp70 binds and recruits various chaperones and E3 ligases, including DNAJB12 and RING membrane-anchor 1 (RMA1) (119, 129, 157, 201). In addition, an Hsp70 cochaperone known as cysteine string protein (Csp) regulates CFTR routing from the ER to the proteosome in part via binding to the CHIP (COOH-terminal Hsp70 interacting protein) ubiquitin ligase and Hsp70 (31, 158, 203).

Upon ER exit, Hsp70 is released from wild-type, properly folded CFTR but remains attached to misfolded species (113, 197). Notably, the E3 ligase MARCH2 (membrane associated RING-CH), together with CAL (CFTR-associated ligand) and STX6 (syntaxin 6), has been reported to ubiquitinate CFTR in the Golgi apparatus and target the protein towards lysosomal degradation (37). In contrast, in post-Golgi compartments (including the cell surface), Hsp70 binds rescued F508del CFTR with a greater affinity than wild-type CFTR and recruits CHIP (137). CHIP preferentially recognizes core and complex glycosylated forms of misfolded CFTR and is key for cell-surface removal of F508del CFTR that has been rescued by low temperature (119, 137).

It is well established that CHIP is a major participant in CFTR quality control; however, the mechanism of action of CHIP is highly dependent on the formation of protein complexes. For example, prolonged interaction of F508del CFTR with Hsp70 and DNAJA1, another Hsp70 cochaperone (also known as Hdj2), recruits CHIP and UbcH5 (an E2 conjugating enzyme) at the ER (Fig. 3). This complex serves as an early quality control check point and promotes degradative ubiquitination of nascent CFTR but may also serve dysfunction in post-Golgi compartments (137, 202). Overexpression of UbcH5 increases ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of both the wild-type and F508del protein, and E3 ligases such as RMA1 recognize misfolded CFTR cotranslationally and complex with Ubc6e (an E2), Derlin-1 (a component of the putative ERAD retrotranslocation channel), CHIP, and Hsp70 to facilitate CFTR destruction (96, 150, 201, 202). In turn, c-Cbl, a plasma membrane E3 ligase, appears to facilitate endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of CFTR in human primary airway epithelial cells (Fig. 3) (198). Other participants during CFTR biogenesis include Hsp70 cochaperones, such as BAG1 and HOP, and the Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 as well as small heat shock proteins (8). While this review provides examples of well-characterized proteins involved in CFTR quality control, the full CFTR ubiquitin/protein quality control network is much more complex with new participants continually being identified. Proteomic analysis to characterize the CFTR interactome, including proteins that bind differentially to F508del vs. wild-type CFTR, has suggested hundreds of such binding interactions. Individual roles for many of these CFTR binding partners remains to be determined (7, 8, 57, 90, 112, 122, 137, 158, 187, 203).

Endosomal sorting of CFTR.

In early endosomes, which contain proteins delivered from either the plasma membrane or the trans-Golgi network, sorting to the lysosome is regulated by ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) complexes comprised of multiple ubiquitin-binding proteins (71, 148). In studies of low temperature-rescued F508del CFTR, knockdown of ESCRT constituents such as Hrs, STAM, and TSG101 stabilize the F508del mutant, suggesting a crucial role for ESCRT in removal of unstable CFTR (55, 137). Endosomal DUBs have also been shown to regulate CFTR sorting (see below).

The diversity of protein ubiquitination.

Ubiquitin attachment to lysine in a target protein can take the form of monoubiquitination or polyubiquitination. Ubiquitin itself is a 76 amino acid protein that contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), each of which can serve as a target for further ubiquitin modification. Polyubiquitination through internal lysines results in structurally varied attachments that convey distinctive signals with regard to protein stability and cellular trafficking (30, 51, 101, 162, 169). Generally, however, K48 ubiquitin attachment provides a signal for proteosomal degradation whereas K63 contributes to endocytic sorting (19, 20, 131, 133). Linkages through K6, K11, and K29 have also been connected to proteosomal targeting (19, 193). Moreover, in some cases, residues other than a lysine can be modified in a protein target (12, 91). Little is known regarding specific linkage types on CFTR; however, one recent study suggests that CFTR is subjected to K63-linked ubiquitin attachment on multiple residues (97).

Deubiquitinating enzymes.

While ubiquitin ligases are numerous and have been extensively studied, there are fewer DUBs (∼100 in the human genome), and their activities and substrate specificities are less well understood (75, 183). What is clear, however, is that DUBs may either rescue proteins from being degraded, or, for those that reside in the proteasome, their activity is essential for degradation. For example, the removal of ubiquitin side chains is necessary immediately before proteosomal degradation since ubiquitin must be recycled and an extended polyubiquitin chain might prevent access to the catalytic core of the proteasome. If the activities of specific DUBs are blocked, polyubiquitinated misfolded proteins can accumulate in the ER and induce an unfolded protein response (UPR) (47, 64). Deubiquitination can also influence specific steps in endosome-dependent degradative processing or protein retrieval to the cell surface. For example, the endosomal DUBs USP8 (ubiquitin-specific protease 8; also called UBPY) and AMSH (associated molecule with the SH3 domain of STAM) promote degradation or recycling to the plasma membrane, respectively (Fig. 3) (117, 118, 127, 152). In addition, AMSH processes K63 (but not K48) ubiquitin side chains (86, 118, 120), whereas USP8 impacts protein degradation mediated by either linkage type via lysosomal targeting (through interactions with ESCRT) and routing to the proteosome (126, 152).

USP19 is an ER-specific DUB that stabilizes core-glycosylated wild-type and F508del CFTR, likely by inhibiting proteasome-dependent ERAD (Fig. 3) (64). In the same manner, the DUB ubiquitin COOH-terminal hydrolase 1 (UCH-L1) stabilizes CFTR by removing ubiquitin in the ER and reduces proteosomal degradation (70). In contrast, deubiquitination by USP10 has been reported to increase levels of wild-type CFTR by enhancing transit from the early endosome to the cell surface (Fig. 3) (23, 24). Interestingly, bacterial toxins have been shown to target DUBs as well as other factors in the ubiquitin pathway (156), and a growing body of evidence indicates the importance of PTM modulation as a general virulence strategy. With regard to CFTR, the presence of Cif, a bacterial toxin released by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, exhibits an inhibitory effect on USP10 which prevents apical recycling of CFTR and diverts the protein to the lysosome (25, 111). Examples of other bacterial products that specifically target PTMs include SopE and SptP from Salmonella, which modulate ubiquitination (93), the Shigella virulence factor IpaJ, which disrupts N-myristoylation (27), and GobX from Legionella, which utilizes host palmitoylation and ubiquitination (105). In addition, bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa may have effects stabilizing CFTR, as well as inhibiting pharmaco-correction by compounds such as VX-809 (166, 175). The mechanism of action has not yet been fully established for these latter findings, but proteins such as USP10 represent a potential therapeutic target by providing a means to improve corrector efficacy in patients infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Site-specific CFTR ubiquitination.

Historically, less emphasis has been placed on identifying specific sites of CFTR ubiquitination and understanding the means by which specifically modified sites affect protein biogenesis. However, advances in protein purification together with high resolution, high mass accuracy mass spectrometry have led to the description of more than 25 discrete locations for CFTR ubiquitination (see Refs. 97, 114 and unpublished data in Ref. 115). Emerging information of this type will enable future studies to define key steps during CFTR trafficking and degradation, including analyses of specific ubiquitin linkage types (e.g., K48 vs. K63) at particular CFTR residues and the determination of the E3 ligases and DUBs that regulate CFTR stability and trafficking. For example, a recent report described the first mechanistic investigation of ubiquitination positions and associated ubiquitin linkage types in CFTR (97). This evidence indicates 1) CFTR NH2-terminal residues K14 and K68 are targets that mediate proteosomal degradation, 2) K710 and K716 (RD) and K1041 (MSD2) are important for CFTR stabilization, and 3) K1218 in NBD2 is likely employed for ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal targeting. Furthermore, numerous sites (such as K710 and K716) appear to undergo K63-linked ubiquitin-binding and may be important stabilizers of mature CFTR. Discrete lysines that influence proteosomal degradation or endocytic sorting, as well as a ubiquitination site on K1218 that prevents apical recycling from the endosome, have also been described (97). These findings will aid CF drug discovery efforts that target the ubiquitination pathway, and site-specific ubiquitination may serve as a read-out for the effects of such compounds or emerge as novel biomarkers. In addition, relationships between the E3 ligases that regulate CFTR biogenesis [including CHIP, RMA1, c-Cbl, gp78, and MARCH2 (37, 129, 137, 150, 198, 201, 202)], and their interacting chaperones and cochaperones, will benefit from a more complete understanding of specific ubiquitin linkage types and the sites of modification.

SUMOylation

Several ubiquitin-like modifiers (Ubls) have been characterized that are appended to target proteins and in some cases function similarly to ubiquitin. For example, at least four small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs) are present in mammals, although only SUMO-1, -2, and -3 appear to be widely expressed (92). In semblance to DUBs, SUMO deconjugation is facilitated by a family of sentrin-specific proteases (SENPs) (85). SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs), such as ring-finger protein 4 (RNF4), can direct SUMOylated polypeptides to proteosomal degradation (73, 167). In addition, SUMOylation has been shown previously to regulate activity of proteins such as the potassium channel Kv1.5 (21). Recent reports indicate that F508del CFTR, as well as other conformationally unstable forms, are SUMOylated (6, 7, 56). This occurs by a mechanism in which a small heat shock protein, Hsp27, associates with nonnative NBD1 and binds Ubc9, which is the only known SUMO E2 conjugating enzyme. SUMOylation of F508del CFTR increases Hsp27-mediated degradation, whereas expression of Senp1 stabilizes the ER-localized (band B) glycoform. Hsp27-mediated degradation of F508del CFTR also requires RNF4, which transfers SUMOylated F508del CFTR to the ubiquitin-proteosome system (UPS). Together, the data point to a novel pathway involved in degradation of conformationally less stable forms of CFTR (6, 7). Of note, effects have been observed on wild-type CFTR when the SUMOylation pathway is altered, suggesting that this mechanism also contributes to modest levels of ERAD that occur for the peptide (7).

While specific sites of SUMO modification in CFTR remain to be identified, predictive algorithms suggest K447 (NBD1) and K1468 (COOH-terminal) via their inclusion in a Ψ-K-X-E consensus sequence as likely targets that may influence CFTR degradation (SUMOsp 2.0; http://sumosp.biocuckoo.org) (205). In addition, it has been reported that the SUMO isoforms can interact noncovalently with other proteins by targeting specific SUMO-interaction motifs. These predictive algorithms also identify two CFTR peptides (616–620 in NBD1 and 1117–1121 in MSD2) as potential SUMO-interaction motifs (84). Significant cross talk between the SUMO and ubiquitin pathways has been demonstrated for several other proteins (73), and the possibility of interaction between CFTR SUMO- and ubiquitin-conjugation represents an important area for future study.

Phosphorylation

Regulation of CFTR gating and domain binding by protein kinase A.

Phosphorylation governs binding interactions, protein stability, cellular localization, and function through signaling cascades involving both kinases and phosphatases. CFTR phosphorylation is best known for its role as a regulator of protein structure and channel gating. Among ABC transporters, CFTR is unique not only because it functions as an ion channel, but because it is the only family membrane to encode a RD (Fig. 1). The CFTR RD is a disordered region that inhibits channel function, perhaps in part due to binding NBD1 and preventing head-to-tail NBD heterodimerization (35, 42, 110, 124). Protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of specific serines in the RD has been suggested to disrupt an inhibitory interaction with NBD1 by increasing RD binding to other regions in CFTR (16, 35). Subsequent ATP-binding and hydrolysis at the NBD1-NBD2 interface facilitate channel gating (16, 29, 39). A total of 15 serines in the RD must be mutated to completely obviate activation by PKA, suggesting that substantial redundancy exists with regard to phosphorylation-dependent regulation of CFTR channel gating (68).

While numerous phosphorylation sites reside in CFTR, S660, S795, and S813 are the most critical targets for channel activation by PKA (Table 1) (17, 190). In contrast, phosphorylation of S768 elicits an inhibitory effect on channel gating, and S737 has been shown to demonstrate both stimulatory and inhibitory effects (17, 43, 178, 190). Time course studies indicate that phosphorylation of S700, S737, and S768 occurs rapidly following exposure to PKA, but S813 exhibits delayed responsiveness that may be cooperatively promoted by prior phosphorylation of S700 and S737 (68). Dephosphorylation of the same amino acid residues may also occur in a hierarchal manner, but this has not been conclusively demonstrated.

Table 1.

Effects of kinases shown to phosphorylate CFTR

| Kinase/Target Residue(s) | CFTR Domain | Suggested Consequence of Phosphorylation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PKA | |||

| S422 | RI | Unknown | 44 |

| S660 | RE | Channel activation; disrupts the NBD1:NBD2 interface | 17, 45, 176 |

| S670 | RE | Channel activation; disrupts the NBD1:NBD2 interface | 45 |

| S700 | RD | Channel activation | 68 |

| S737 | RD | Channel activation or inhibition | 17, 43, 68, 178, 190 |

| S768 | RD | Channel inhibition | 17, 43, 68, 178, 190 |

| S795 | RD | Channel activation | 17, 190 |

| S813 | RD | Channel activation | 17, 68, 89, 190 |

| AMPK | |||

| S737 | RD | Channel inhibition; blocks activation from PKA phosphorylation | 87, 185 |

| S768 | RD | Channel inhibition; blocks activation from PKA phosphorylation | 87, 185 |

| S813 | RD | Channel inhibition | 89 |

| PKC | |||

| S686 | RD | Enhances PKA-dependent binding of RD to other CFTR domains | 34, 78, 81 |

| S790 | RD | Enhances PKA-dependent binding of RD to other CFTR domains | 34, 78, 81 |

| CK2 | |||

| S422 | RI | Stabilizes trafficking and thus activation | 109, 173 |

| S511 | NBD1 | Channel activation; may interact with SYK phosphorylation at Y512 | 109, 173 |

| T1471 | COOH terminal | Decreases chloride conductance by decreasing trafficking | 109, 173 |

| SYK | |||

| Y512 | NBD1 | Reduces expression at the cell surface; regulates phosphorylation by CK2 | 109, 121 |

| PI3K | |||

| Unknown | — | Promotes trafficking to the cell surface | 176 |

| WNK4 | |||

| Y512 | NBD1 | Inhibits SYK phosphorylation; promotes expression at the cell surface | 121 |

| CaMKI | |||

| Unknown | — | Unknown | 144 |

| p60c-src | |||

| Unknown | — | Regulates channel open probability | 49 |

| PKGII | |||

| Unknown | — | Channel activation | 144, 177 |

| LMTK2 | |||

| S737 | RD | Facilitates endocytosis of CFTR from the cell surface | 108 |

CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; NBD1, nucleotide binding domain; RD, regulatory domain; RI, regulatory insertion.

NBD1 encodes a 31 amino acid region termed the regulatory insertion (RI), which also contains a consensus PKA phosphorylation site at S422 (Fig. 1 and Table 1) (44, 45). In addition, the NH2-terminal portion of the RD includes a regulatory extension (RE) that adjoins NBD1 and contains two PKA consensus phosphorylation sites (S660 and S670). The RE is thought to interact directly with NBD1. Phosphorylation of the RI results in a conformational change that disrupts interaction with the NBD core, likely by promoting NBD1 binding to intracellular loop 1 (ICL1; also referred to as the coupling helix 1) (81, 190). NMR studies further suggest that phosphorylation disrupts interaction of the NBD1 core with RE and RI phosphoregulatory regions. Notably, the structural changes elicited by RI and RE phosphorylation are absent or significantly reduced in F508del CFTR, a result supported by homology modeling with specific CFTR domains (81). This observation may also help explain the persistent gating defects seen in rescued F508del CFTR (143).

Numerous other kinases phosphorylate CFTR.

Multiple protein kinases regulate CFTR phosphorylation, including protein kinase C (PKC; Table 1) (17, 34, 68, 144, 160, 190). Binding of the RD to other regions in CFTR is increased due to PKA- or PKC-mediated phosphorylation and may be strongest following phosphorylation by both kinases (34, 78, 160). PKC directly binds CFTR and is believed to phosphorylate S686 and S790. Several other PKC consensus sites have also been identified, suggesting the likelihood of additional targets (33, 144, 160). Phosphorylation of CFTR by adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) inhibits PKA-mediated channel activation by competing for key binding sites (59–61, 87, 89, 185). As such, inhibition of AMPK increases channel open probability through effects dependent on S768, and to a lesser extent S737 (87, 89), which are also sensitive to PKA (43, 190). Mutating S768A/S737A results in a channel that retains partial activity in response to AMPK, suggesting that additional sites are phosphorylated by the kinase (89). In support of this notion, protein interaction studies indicate that both PKA and AMPK directly bind near and phosphorylate S813. Competition between AMPK and PKA for this position (and differential consequences of posttranslational modification of these residues) may depend on the RD conformation (164). In addition, AMPK phosphorylation appears to diminish channel activation by PKA or PKC but does not completely prevent CFTR phosphorylation by these enzymes (87). Residues T717, S1444, and S1456 have also been implicated as targets of phosphorylation, although the responsible kinases have not yet been identified (114).

A number of additional kinases regulate CFTR activity (Table 1). For example, phosphorylation by casein kinase 2 (CK2) activates CFTR chloride conductance. Of the three CK2 consensus sequences, phosphorylation of S422 reportedly stimulates chloride transport, S511 exhibits minimal effects on channel function, and T1471 has been reported to decrease activity by disrupting trafficking to the cell surface (109, 173). Coimmunoprecipitation data indicate direct binding between CK2 and wild-type but not F508del CFTR, and inhibition of the kinase significantly reduced chloride currents of the wild-type but not F508del protein (173). This phenomenon may arise from the inability of F508del CFTR to reach the cell surface where the relevant phosphorylation events occur.

The cytosolic spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) has been reported to phosphorylate Y512 and regulate CK2-mediated activity, possibly by interacting with the CK2 consensus site S511. Unlike CK2, SYK binds both the wild-type and F508del protein, and its expression decreases CFTR localization to the cell surface (109, 121). Another kinase, LMTK2, has been reported to have a phospho-inhibitory effect on CFTR by modifying S737 in human airway epithelial cells (108). Furthermore, knockdown of LMTK2 facilitates corrector (i.e., VX-809)-mediated rescue of F508del CFTR, resulting in increased levels of band C and Isc in CFBE monolayers. Additional kinases reported to modulate CFTR activity (either through direct phosphorylation of CFTR itself or via secondary effects mediated by other proteins) include tyrosine kinase p60c-src, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase I (CaMKI), cGMP-dependent kinase [also referred to as protein kinase G (PKG)], phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), with-no-lysine 4 (WNK4), and receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) (14, 49, 103, 121, 144, 176, 177). Data on the targets and effects of these kinases are outlined in Table I.

While phosphorylation of specific RD serines has been shown to influence NBD1-RD interaction, the mechanism by which phosphorylation at other sites regulates channel gating is less well understood. Such effects could be a result of occluding or exposing sites for protein binding partners. For example, PKA/cAMP-mediated phosphorylation of the RD in CFTR increases binding of the 14-3-3β protein, which in turn stabilizes immature CFTR expression and augments conversion to the mature glycoform Band C (102). 14-3-3β reduces CFTR interaction with COPI, suggesting the effect on maturational processing may result from blocking retrograde transport of CFTR from the Golgi and ERAD (102). Phosphorylation has also been implicated in clathrin-dependent endocytosis, where PKA and PKC activity reduce internalization rates of CFTR from the cell surface (106).

Phosphatase activity and CFTR function.

Few studies have characterized the enzymes that dephosphorylate CFTR. Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) reduces CFTR channel conductance, but failure to abolish CFTR function suggests involvement of additional phosphatases. The importance of PP2C is further supported by the observation that CFTR directly binds PP2C but not PP1, PP2A, or PP2B (44, 172, 207). Studies to address the phosphatases that regulate CFTR, as well as the specific residues they target, are vital to better define the mechanisms by which CFTR is regulated.

Coordinate regulation of PTMs.

Cross talk between phosphorylation and other PTMs, such as ubiquitination and SUMOylation, has been observed for numerous proteins. Regulation of this sort may be described as positive or negative. For example, with regard to positive cross talk, attachment of one PTM must be present in order for covalent attachment at a second site to occur. In this context, phosphate additions to certain sites on IkB (a nuclear factor-κB inhibitory protein) are necessary for establishment of the recognition sequence for a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, which leads to ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis. Site-specific mutation of the relevant phosphorylation positions mediates resistance to proteosomal degradation (82). The extent of such positive interactions for the CF gene product are not known [see above for an example involving glycosylated CFTR and CHIP (119, 138)], but such mechanisms may provide molecular targets important for preventing premature degradation of nonnative CFTR.

With regard to negative cross talk, side chain attachment at one site precludes a second PTM. While modifications such as these could have effects at a distance, a recent proteomic analysis provided evidence that negative interactions (also termed molecular switches) occur most frequently at protein positions separated by less than four residues (191). In CFTR, several PTMs have been identified that reside in close proximity to each other. For example, one well characterized phosphorylation site, S686, is important in CFTR domain interaction and activation (34). A recent report identified ubiquitination at nearby lysine 688 (114). While the significance of K688 ubiquitination in unclear, it is reasonable to imagine that covalent attachment of ubiquitin at this site might impair phosphorylation of S686, thereby blocking domain interactions necessary for channel activation. In any case, future studies of cross talk among numerous PTMs located within CFTR are likely to reveal unappreciated features of regulation that influence trafficking, function, and perhaps also pharmacotherapy.

Palmitoylation

Mechanism of palmitoylation.

Over the past decade, growing emphasis has been placed on the importance of palmitoylation as a regulator of protein biogenesis. Recent findings have identified relevance of this modification during biogenesis of wild-type and F508del CFTR (114, 116). Palmitoylation is characterized by the thioester linkage of a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid to cysteine residues (Fig. 4). Palmitate attachment is governed by protein acyl transferases (PATs; also known as palmitoyltransferases), a family of 23 gene products in mammals that contain a conserved DHHC motif in a cysteine-rich catalytic domain (174). The NH2 and COOH termini of PATs vary substantially and are believed to confer substrate specificity. Unlike other types of acyl modification, palmitoylation is reversible. Although the deconjugation events are less well understood, thioesterases such as APT1 (acyl protein thioesterase 1), APT2, APT1-like, and PPT1 (palmitoyl protein thioesterase 1) have been implicated as mediators of palmitate side chain removal (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of S-palmitoylation. Palmitate attachment occurs through thioester bonds to sulfhydryls on cysteine residues. Transfer of palmitate from the coenzyme A intermediate is performed via members of the protein acyl transferase gene family. Unlike other lipid modifications, palmitoylation is reversible; palmitate can be removed by acyl protein thioesterases or palmitoyl protein thioesterases.

Palmitoylation of membrane proteins.

Attachment of palmitate to cytosolic proteins typically augments membrane association and may occur in conjunction with N-myristoylation or prenylation (9). The effects of integral membrane protein palmitoylation are still actively being investigated, but it is clear that this modification can alter the orientation of a substrate in the membrane, the sorting of an integral membrane protein to a specific subcellular compartment, and the modulation of other sidechain attachments. For example, palmitoylation regulates insertion of the GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptor into the plasma membrane (104), governs recycling of MUC1 and the GABA-A receptor from the cell surface (88, 149), regulates channel gating of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) (130), and mediates cell surface trafficking of ABCA1, a member of the same gene family as CFTR (163). In lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), attachment of palmitate to two juxtamembranous cysteines induces a tilt in the membrane-spanning segment, thereby reducing its effective hydrophobic length. In the absence of palmitoylation, the protein is unable to enter COPII-coated vesicles for transport to the Golgi (2). Palmitoylation also targets membrane proteins to alternate cellular or subcellular compartments. For example, palmitoylation of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR-1) confers localization to caveolin-rich microdomains, thereby favoring its interaction with Gα (65). Similarly, palmitoylation of AMPAR subunits restricts the protein to the ER and may prevent lysosomal targeting (195).

Palmitoylation of CFTR.

Following purification of full-length recombinant CFTR from HEK293 cells, mass spectrometry established S-palmitoylation on at least two residues: cysteine 524 (located within NBD1) and cysteine 1395 (in the COOH-terminal region of the protein) (114). Experience with other membrane proteins suggests that multiple CFTR residues (in addition to those described here) are likely to be palmitoylated. Blocking cellular palmitoylation with 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP), a pharmacologic inhibitor of this modification, disrupts biogenesis of wild-type and low-temperature corrected F508del CFTR and results in decreased chloride transport, as demonstrated by halide efflux assay. While the effects of palmitate-attachment at C1395 are unclear, mutation of another palmitoylation target, C524, results in an unstable protein that is prematurely degraded (116). Analysis by patch clamp assay demonstrates that the conductance of C524S CFTR is similar to that of the wild-type protein if it reaches the cell surface (63).

DHHC-7 is a PAT that palmitoylates wild-type and F508del CFTR and stabilizes both proteins in the Golgi (116). DHHC-7 coimmunoprecipitates strongly with both wild-type and F508del CFTR, although the precise binding site has not yet been determined. The finding that specific PATs dramatically increase the amount of core glycosylated F508del CFTR (Band B) and sequester the protein in the Golgi is significant, since the mutant CFTR is otherwise ER-localized and rapidly degraded by ERAD. As described above, high-throughput molecular library screens have identified small molecule correctors of F508del CFTR misprocessing. Such compounds might act directly to ameliorate the F508del folding defect, or they could influence (non-CFTR) cellular proteins that impact processing or quality control. In this context, PATs such as DHHC-7, as well as enzymes responsible for depalmitoylation, should be considered as potential molecular targets with relevance to F508del CFTR rescue.

The interplay between palmitoylation and other PTMs.

Like many other covalent modifications to amino acid side chains described above, allosteric effects due to palmitate can influence the attachment of posttranslational modifications to other, nearby residues. For example, phosphorylation of S816 and S818 of the GluR1 subunit of AMPAR is required for trafficking to the cell surface. Palmitoylation of C811, which resides nearby, blocks phosphorylation and prevents cell surface residence (104). In a similar fashion, palmitoylation of LRP6 inhibits ubiquitination on a proximate lysine that is otherwise monoubiquitinated and targets the protein for degradation (2). Palmitoylation of the STREX (stress axis regulated exon) insert of the large conductance potassium (BK) channel results in transport activation by preventing kinase access to an inhibitory phosphorylation site (170, 206). Interactions such as these are also likely to occur in CFTR, since the protein is phosphorylated or palmitoylated at numerous residues in close proximity to sites of ubiquitination.

Summary

The diverse manifestations of PTMs with regard to both CFTR biochemistry and CF disease mechanism are illustrated by the present review. Posttranslational side chain attachments contribute to biogenesis, regulation, and/or activity of many integral membrane proteins, and our understanding of these processes in relation to CFTR has advanced rapidly. Specific PTMs have been implicated as contributors to pathogenesis in numerous clinical settings other than CF, including neoplasia (1, 98), heart disease (15, 123), infection/inflammation (10, 76, 179), and neurodegenerative conditions (5, 41), among others. The present review highlights a crucial role for covalent protein modifications as part of the CF disease mechanism.

Conclusions

More than 1,900 mutations, ∼40% of which are missense mutations, are currently listed in the CFTR Mutation Database and/or Clinical and Functional Translation of CFTR (CFTR2) website (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca; http://www.cftr2.org). Many of these alterations confer clinical disease. It is noteworthy that some of the posttranslational modifications reviewed in this article coincide with known CFTR defects. For example, mutation of lysine 68, a site of ubiquitin attachment, has been reported in a CF patient with mild lung disease (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca). It is also likely that many of the mutations confer effects on PTMs at a distance, thus altering CFTR trafficking, stability, folding, degradation, and/or function. Therefore, a more complete analysis of CFTR PTMs may help define key steps that regulate or augment CFTR biogenesis, as well as novel mechanisms that underlie disease-associated variants. An improved understanding of CFTR PTMs will also facilitate identification of therapeutic targets suitable for rescue of mutations responsible for clinical disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-075061 and DK-079307 and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Grant BRODSK13XX0 (to J. L. Brodsky) and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Grant SORSCH13XX0 (to E. J. Sorscher).

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Sorscher participates as a subcontractee on an NIH SBIR from Progenra, Inc., investigating targetable posttranslational modifications for CF therapy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L.M. prepared figures; M.L.M. drafted manuscript; M.L.M., S.B., J.L.B., and E.J.S. edited and revised manuscript; E.J.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aasebo E, Forthun RB, Berven F, Selheim F, Hernandez-Valladares M. Global cell proteome profiling, phospho-signaling and quantitative proteomics for identification of new biomarkers in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 17: 52–70, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrami L, Kunz B, Iacovache I, van der Goot FG. Palmitoylation and ubiquitination regulate exit of the Wnt signaling protein LRP6 from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5384–5389, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accurso FJ, Rowe SM, Clancy JP, Boyle MP, Dunitz JM, Durie PR, Sagel SD, Hornick DB, Konstan MW, Donaldson SH, Moss RB, Pilewski JM, Rubenstein RC, Uluer AZ, Aitken ML, Freedman SD, Rose LM, Mayer-Hamblett N, Dong Q, Zha J, Stone AJ, Olson ER, Ordonez CL, Campbell PW, Ashlock MA, Ramsey BW. Effect of VX-770 in persons with cystic fibrosis and the G551D-CFTR mutation. N Engl J Med 363: 1991–2003, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aebi M. N-linked protein glycosylation in the ER. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833: 2430–2437, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed T, Zahid S, Mahboob A, Farhat SM. Cholinergic system and post-translational modifications: an insight on the role in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Neuropharmacol 2016. March 25 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahner A, Gong X, Frizzell RA. CFTR degradation: cross-talk between the ubiquitylation and SUMOylation pathways. FEBS J 280: 4430–4438, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahner A, Gong X, Schmidt BZ, Peters KW, Rabeh WM, Thibodeau PH, Lukacs GL, Frizzell RA. Small heat shock proteins target mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator for degradation via a small ubiquitin-like modifier-dependent pathway. Mol Biol Cell 24: 74–84, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahner A, Nakatsukasa K, Zhang H, Frizzell RA, Brodsky JL. Small heat-shock proteins select deltaF508-CFTR for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Mol Biol Cell 18: 806–814, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aicart-Ramos C, Valero RA, Rodriguez-Crespo I. Protein palmitoylation and subcellular trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808: 2981–2994, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akbarali HI, Kang M. Postranslational modification of ion channels in colonic inflammation. Curr Neuropharmacol 13: 234–238, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ameen N, Silvis M, Bradbury NA. Endocytic trafficking of CFTR in health and disease. J Cyst Fibros 6: 1–14, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anania VG, Bustos DJ, Lill JR, Kirkpatrick DS, Coscoy L. A novel peptide-based SILAC method to identify the posttranslational modifications provides evidence for unconventional ubiquitination in the ER-associated degradation pathway. Int J Proteomics 2013: 857918, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appenzeller-Herzog C, Nyfeler B, Burkhard P, Santamaria I, Lopez-Otin C, Hauri HP. Carbohydrate- and conformation-dependent cargo capture for ER-exit. Mol Biol Cell 16: 1258–1267, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auerbach M, Liedtke CM. Role of the scaffold protein RACK1 in apical expression of CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C294–C304, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aune SE, Herr DJ, Kutz CJ, Menick DR. Histone deacetylases exert class-specific roles in conditioning the brain and heart against acute ischemic injury. Front Neurol 6: 145, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker JM, Hudson RP, Kanelis V, Choy WY, Thibodeau PH, Thomas PJ, Forman-Kay JD. CFTR regulatory region interacts with NBD1 predominantly via multiple transient helices. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 738–745, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldursson O, Berger HA, Welsh MJ. Contribution of R domain phosphoserines to the function of CFTR studied in Fischer rat thyroid epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279: L835–L841, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bannykh SI, Bannykh GI, Fish KN, Moyer BD, Riordan JR, Balch WE. Traffic pattern of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator through the early exocytic pathway. Traffic 1: 852–870, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bedford L, Layfield R, Mayer RJ, Peng J, Xu P. Diverse polyubiquitin chains accumulate following 26S proteasomal dysfunction in mammalian neurones. Neurosci Lett 491: 44–47, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belzile JP, Richard J, Rougeau N, Xiao Y, Cohen EA. HIV-1 Vpr induces the K48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of target cellular proteins to activate ATR and promote G2 arrest. J Virol 84: 3320–3330, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson MD, Li QJ, Kieckhafer K, Dudek D, Whorton MR, Sunahara RK, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Martens JR. SUMO modification regulates inactivation of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 1805–1810, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benyair R, Ogen-Shtern N, Lederkremer GZ. Glycan regulation of ER-associated degradation through compartmentalization. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bomberger JM, Barnaby RL, Stanton BA. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP10 regulates the endocytic recycling of CFTR in airway epithelial cells. Channels (Austin) 4: 150–154, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bomberger JM, Barnaby RL, Stanton BA. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP10 regulates the post-endocytic sorting of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 284: 18778–18789, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bomberger JM, Ye S, Maceachran DP, Koeppen K, Barnaby RL, O'Toole GA, Stanton BA. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin that hijacks the host ubiquitin proteolytic system. PLoS Pathog 7: e1001325, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brodsky JL, Frizzell RA. A combination therapy for cystic fibrosis. Cell 163: 17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burnaevskiy N, Fox TG, Plymire DA, Ertelt JM, Weigele BA, Selyunin AS, Way SS, Patrie SM, Alto NM. Proteolytic elimination of N-myristoyl modifications by the Shigella virulence factor IpaJ. Nature 496: 106–109, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burns DM, Touster O. Purification and characterization of glucosidase II, an endoplasmic reticulum hydrolase involved in glycoprotein biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 257: 9990–10000, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carson MR, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. The two nucleotide-binding domains of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) have distinct functions in controlling channel activity. J Biol Chem 270: 1711–1717, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castaneda CA, Kashyap TR, Nakasone MA, Krueger S, Fushman D. Unique structural, dynamical, and functional properties of k11-linked polyubiquitin chains. Structure 21: 1168–1181, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD. Activation of the ATPase activity of heat-shock proteins Hsc70/Hsp70 by cysteine-string protein. Biochem J 322: 853–858, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang XB, Mengos A, Hou YX, Cui L, Jensen TJ, Aleksandrov A, Riordan JR, Gentzsch M. Role of N-linked oligosaccharides in the biosynthetic processing of the cystic fibrosis membrane conductance regulator. J Cell Sci 121: 2814–2823, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chappe V, Hinkson DA, Howell LD, Evagelidis A, Liao J, Chang XB, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Stimulatory and inhibitory protein kinase C consensus sequences regulate the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 390–395, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chappe V, Hinkson DA, Zhu T, Chang XB, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Phosphorylation of protein kinase C sites in NBD1 and the R domain control CFTR channel activation by PKA. J Physiol 548: 39–52, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chappe V, Irvine T, Liao J, Evagelidis A, Hanrahan JW. Phosphorylation of CFTR by PKA promotes binding of the regulatory domain. EMBO J 24: 2730–2740, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chavan M, Lennarz W. The molecular basis of coupling of translocation and N-glycosylation. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 17–20, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng J, Guggino W. Ubiquitination and degradation of CFTR by the E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH2 through its association with adaptor proteins CAL and STX6. PLoS One 8: e68001, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O'Riordan CR, Smith AE. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell 63: 827–834, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng SH, Rich DP, Marshall J, Gregory RJ, Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Phosphorylation of the R domain by cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates the CFTR chloride channel. Cell 66: 1027–1036, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cholon DM, O'Neal WK, Randell SH, Riordan JR, Gentzsch M. Modulation of endocytic trafficking and apical stability of CFTR in primary human airway epithelial cultures. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L304–L314, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conti A, Alessio M. Comparative proteomics for the evaluation of protein expression and modifications in neurodegenerative diseases. Int Rev Neurobiol 121: 117–152, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Csanady L, Chan KW, Seto-Young D, Kopsco DC, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Severed channels probe regulation of gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by its cytoplasmic domains. J Gen Physiol 116: 477–500, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Csanady L, Seto-Young D, Chan KW, Cenciarelli C, Angel BB, Qin J, McLachlin DT, Krutchinsky AN, Chait BT, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Preferential phosphorylation of R-domain Serine 768 dampens activation of CFTR channels by PKA. J Gen Physiol 125: 171–186, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahan D, Evagelidis A, Hanrahan JW, Hinkson DA, Jia Y, Luo J, Zhu T. Regulation of the CFTR channel by phosphorylation. Pflugers Arch 443, Suppl 1: S92–96, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dawson JE, Farber PJ, Forman-Kay JD. Allosteric coupling between the intracellular coupling helix 4 and regulatory sites of the first nucleotide-binding domain of CFTR. PLoS One 8: e74347, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deprez P, Gautschi M, Helenius A. More than one glycan is needed for ER glucosidase II to allow entry of glycoproteins into the calnexin/calreticulin cycle. Mol Cell 19: 183–195, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eletr ZM, Wilkinson KD. Regulation of proteolysis by human deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem 78: 477–513, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fischer H, Machen TE. The tyrosine kinase p60c-src regulates the fast gate of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Biophys J 71: 3073–3082, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fulmer SB, Schwiebert EM, Morales MM, Guggino WB, Cutting GR. Two cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutations have different effects on both pulmonary phenotype and regulation of outwardly rectified chloride currents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 6832–6836, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fushman D, Walker O. Exploring the linkage dependence of polyubiquitin conformations using molecular modeling. J Mol Biol 395: 803–814, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gadsby DC, Vergani P, Csanady L. The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis. Nature 440: 477–483, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gee HY, Noh SH, Tang BL, Kim KH, Lee MG. Rescue of deltaF508-CFTR trafficking via a GRASP-dependent unconventional secretion pathway. Cell 146: 746–760, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilbert A, Jadot M, Leontieva E, Wattiaux-De Coninck S, Wattiaux R. Delta F508 CFTR localizes in the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment in cystic fibrosis cells. Exp Cell Res 242: 144–152, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glozman R, Okiyoneda T, Mulvihill CM, Rini JM, Barriere H, Lukacs GL. N-glycans are direct determinants of CFTR folding and stability in secretory and endocytic membrane traffic. J Cell Biol 184: 847–862, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gong X, Ahner A, Roldan A, Lukacs GL, Thibodeau PH, Frizzell RA. Non-native conformers of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator NBD1 are recognized by Hsp27 and conjugated to SUMO-2 for degradation. J Biol Chem 291: 2004–2017, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grove DE, Fan CY, Ren HY, Cyr DM. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated Hsp40 DNAJB12 and Hsc70 cooperate to facilitate RMA1 E3-dependent degradation of nascent CFTRDeltaF508. Mol Biol Cell 22: 301–314, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haardt M, Benharouga M, Lechardeur D, Kartner N, Lukacs GL. C-terminal truncations destabilize the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator without impairing its biogenesis. A novel class of mutation. J Biol Chem 274: 21873–21877, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hallows KR, Kobinger GP, Wilson JM, Witters LA, Foskett JK. Physiological modulation of CFTR activity by AMP-activated protein kinase in polarized T84 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C1297–C1308, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hallows KR, McCane JE, Kemp BE, Witters LA, Foskett JK. Regulation of channel gating by AMP-activated protein kinase modulates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activity in lung submucosal cells. J Biol Chem 278: 998–1004, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hallows KR, Raghuram V, Kemp BE, Witters LA, Foskett JK. Inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by novel interaction with the metabolic sensor AMP-activated protein kinase. J Clin Invest 105: 1711–1721, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hammond C, Braakman I, Helenius A. Role of N-linked oligosaccharide recognition, glucose trimming, and calnexin in glycoprotein folding and quality control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 913–917, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrington MA, Kopito RR. Cysteine residues in the nucleotide binding domains regulate the conductance state of CFTR channels. Biophys J 82: 1278–1292, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hassink GC, Zhao B, Sompallae R, Altun M, Gastaldello S, Zinin NV, Masucci MG, Lindsten K. The ER-resident ubiquitin-specific protease 19 participates in the UPR and rescues ERAD substrates. EMBO Rep 10: 755–761, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heakal Y, Woll MP, Fox T, Seaton K, Levenson R, Kester M. Neurotensin receptor-1 inducible palmitoylation is required for efficient receptor-mediated mitogenic-signaling within structured membrane microdomains. Cancer Biol Ther 12: 427–435, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hebert DN, Foellmer B, Helenius A. Glucose trimming and reglucosylation determine glycoprotein association with calnexin in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 81: 425–433, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heda GD, Tanwani M, Marino CR. The ΔF508 mutation shortens the biochemical half-life of plasma membrane CFTR in polarized epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C166–C174, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hegedus T, Aleksandrov A, Mengos A, Cui L, Jensen TJ, Riordan JR. Role of individual R domain phosphorylation sites in CFTR regulation by protein kinase A. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788: 1341–1349, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Helenius A, Aebi M. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 1019–1049, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Henderson MJ, Vij N, Zeitlin PL. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 protects cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from early stages of proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem 285: 11314–11325, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell 21: 77–91, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hosokawa N, Wada I, Hasegawa K, Yorihuzi T, Tremblay LO, Herscovics A, Nagata K. A novel ER alpha-mannosidase-like protein accelerates ER-associated degradation. EMBO Rep 2: 415–422, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hunter T, Sun H. Crosstalk between the SUMO and ubiquitin pathways. Ernst Schering Found Symp Proc 1–16, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hutt DM, Roth DM, Chalfant MA, Youker RT, Matteson J, Brodsky JL, Balch WE. FK506 binding protein 8 peptidylprolyl isomerase activity manages a late stage of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) folding and stability. J Biol Chem 287: 21914–21925, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacq X, Kemp M, Martin NM, Jackson SP. Deubiquitylating enzymes and DNA damage response pathways. Cell Biochem Biophys 67: 25–43, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jeng MY, Ali I, Ott M. Manipulation of the host protein acetylation network by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 50: 314–325, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jensen TJ, Loo MA, Pind S, Williams DB, Goldberg AL, Riordan JR. Multiple proteolytic systems, including the proteasome, contribute to CFTR processing. Cell 83: 129–135, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jia Y, Mathews CJ, Hanrahan JW. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C is required for acute activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 272: 4978–4984, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jih KY, Hwang TC. Vx-770 potentiates CFTR function by promoting decoupling between the gating cycle and ATP hydrolysis cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 4404–4409, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kalies KU, Rapoport TA, Hartmann E. The beta subunit of the Sec61 complex facilitates cotranslational protein transport and interacts with the signal peptidase during translocation. J Cell Biol 141: 887–894, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kanelis V, Hudson RP, Thibodeau PH, Thomas PJ, Forman-Kay JD. NMR evidence for differential phosphorylation-dependent interactions in WT and deltaF508 CFTR. EMBO J 29: 263–277, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol 18: 621–663, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kawasaki N, Ichikawa Y, Matsuo I, Totani K, Matsumoto N, Ito Y, Yamamoto K. The sugar-binding ability of ERGIC-53 is enhanced by its interaction with MCFD2. Blood 111: 1972–1979, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kerscher O. SUMO junction-what's your function? New insights through SUMO-interacting motifs. EMBO Rep 8: 550–555, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim JH, Baek SH. Emerging roles of desumoylating enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1792: 155–162, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim MS, Kim JA, Song HK, Jeon H. STAM-AMSH interaction facilitates the deubiquitination activity in the C-terminal AMSH. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 351: 612–618, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.King JD Jr, Fitch AC, Lee JK, McCane JE, Mak DO, Foskett JK, Hallows KR. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of the R domain inhibits PKA stimulation of CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C94–C101, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kinlough CL, McMahan RJ, Poland PA, Bruns JB, Harkleroad KL, Stremple RJ, Kashlan OB, Weixel KM, Weisz OA, Hughey RP. Recycling of MUC1 is dependent on its palmitoylation. J Biol Chem 281: 12112–12122, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kongsuphol P, Cassidy D, Hieke B, Treharne KJ, Schreiber R, Mehta A, Kunzelmann K. Mechanistic insight into control of CFTR by AMPK. J Biol Chem 284: 5645–5653, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koulov AV, LaPointe P, Lu B, Razvi A, Coppinger J, Dong MQ, Matteson J, Laister R, Arrowsmith C, Yates JR 3rd, Balch WE. Biological and structural basis for Aha1 regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity in maintaining proteostasis in the human disease cystic fibrosis. Mol Biol Cell 21: 871–884, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Ciechanover A. Non-canonical ubiquitin-based signals for proteasomal degradation. J Cell Sci 125: 539–548, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krumova P, Weishaupt JH. Sumoylation in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 70: 2123–2138, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kubori T, Galan JE. Temporal regulation of salmonella virulence effector function by proteasome-dependent protein degradation. Cell 115: 333–342, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kukushkin NV, Alonzi DS, Dwek RA, Butters TD. Demonstration that endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of glycoproteins can occur downstream of processing by endomannosidase. Biochem J 438: 133–142, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. Glycosyltransferases: structures SG, functions, mechanisms. Annu Rev Biochem 77: 521–555, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lau JB, Stork S, Moog D, Sommer MS, Maier UG. N-terminal lysines are essential for protein translocation via a modified ERAD system in complex plastids. Mol Microbiol 96: 609–620, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee S, Henderson MJ, Schiffhauer E, Despanie J, Henry K, Kang PW, Walker D, McClure ML, Wilson L, Sorscher EJ, Zeitlin PL. Interference with ubiquitination in CFTR modifies stability of core glycosylated and cell surface pools. Mol Cell Biol 34: 2554–2565, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Leehy KA, Regan Anderson TM, Daniel AR, Lange CA, Ostrander JH. Modifications to glucocorticoid and progesterone receptors alter cell fate in breast cancer. J Mol Endocrinol 56: R99–R114, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Leitman J, Ron E, Ogen-Shtern N, Lederkremer GZ. Compartmentalization of endoplasmic reticulum quality control and ER-associated degradation factors. DNA Cell Biol 32: 2–7, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leymarie N, Zaia J. Effective use of mass spectrometry for glycan and glycopeptide structural analysis. Anal Chem 84: 3040–3048, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li W, Ye Y. Polyubiquitin chains: functions, structures, mechanisms. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2397–2406, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liang X, Da Paula AC, Bozoky Z, Zhang H, Bertrand CA, Peters KW, Forman-Kay JD, Frizzell RA. Phosphorylation-dependent 14-3-3 protein interactions regulate CFTR biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 23: 996–1009, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liedtke CM, Yun CH, Kyle N, Wang D. Protein kinase C epsilon-dependent regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator involves binding to a receptor for activated C kinase (RACK1) and RACK1 binding to Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factor. J Biol Chem 277: 22925–22933, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lin DT, Makino Y, Sharma K, Hayashi T, Neve R, Takamiya K, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor extrasynaptic insertion by 4.1N, phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Nat Neurosci 12: 879–887, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lin YH, Doms AG, Cheng E, Kim B, Evans TR, Machner MP. Host cell-catalyzed S-palmitoylation mediates golgi targeting of the legionella ubiquitin ligase GobX. J Biol Chem 290: 25766–25781, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lukacs GL, Segal G, Kartner N, Grinstein S, Zhang F. Constitutive internalization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator occurs via clathrin-dependent endocytosis and is regulated by protein phosphorylation. Biochem J 328: 353–361, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lukacs GL, Verkman AS. CFTR: folding, misfolding and correcting the DeltaF508 conformational defect. Trends Mol Med 18: 81–91, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luz S, Cihil KM, Brautigan DL, Amaral MD, Farinha CM, Swiatecka-Urban A. LMTK2-mediated phosphorylation regulates CFTR endocytosis in human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 289: 15080–15093, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Luz S, Kongsuphol P, Mendes AI, Romeiras F, Sousa M, Schreiber R, Matos P, Jordan P, Mehta A, Amaral MD, Kunzelmann K, Farinha CM. Contribution of casein kinase 2 and spleen tyrosine kinase to CFTR trafficking and protein kinase A-induced activity. Mol Cell Biol 31: 4392–4404, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]