Abstract

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a nuclear protein released extracellularly in response to infection or injury, where it activates immune responses and contributes to the pathogenesis of kidney dysfunction in sepsis and sterile inflammatory disorders. Recently, we demonstrated that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in perfused rat medullary thick ascending limbs (MTAL) through a basolateral receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)-dependent pathway that is additive to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-ERK-mediated inhibition by LPS (Good DW, George T, Watts BA III. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F720–F730, 2015). Here, we examined signaling and transport mechanisms that mediate inhibition by HMGB1. Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 was eliminated by the Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y27632 and by a specific inhibitor of Rho, the major upstream activator of ROCK. HMGB1 increased RhoA and ROCK1 activity. HMGB1-induced ROCK1 activation was eliminated by the RAGE antagonist FPS-ZM1 and by inhibition of Rho. The Rho and ROCK inhibitors had no effect on inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath LPS. Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 was eliminated by bath amiloride, 0 Na+ bath, and the F-actin stabilizer jasplakinolide, three conditions that selectively prevent inhibition of MTAL HCO3− absorption mediated through NHE1. HMGB1 decreased basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity through activation of ROCK. We conclude that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through a RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 signaling pathway coupled to inhibition of NHE1. The HMGB1-RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 pathway thus represents a potential target to attenuate MTAL dysfunction during sepsis and other inflammatory disorders. HMGB1 and LPS inhibit HCO3− absorption through different receptor signaling and transport mechanisms, which enables these pathogenic mediators to act directly and independently to impair MTAL function.

Keywords: HMGB1, ROCK, sepsis, kidney, NHE1

high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a ubiquitously expressed nuclear protein that serves both intranuclear and extracellular functions. In the nucleus, HMGB1 binds to DNA and is involved in the maintenance of chromatin structure and regulation of gene transcription (8). In addition to its nuclear role, HMGB1 can be released by cells into the extracellular fluid in response to various stimuli, where it displays immunological activities and functions as an endogenous damage-associated molecule to trigger inflammation (4). HMGB1 is released by immune and nonimmune cells through two major pathways: 1) active secretion in response to infectious or other inflammatory stimuli, including LPS, TNF, and IL-1β; and 2) passive release in response to cell injury or death, when the integrity of cell permeability barriers is compromised (4, 59, 60, 107). Once outside the cell, HMGB1 interacts with cell surface receptors such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) to mediate innate immune and inflammatory responses (4, 40, 60, 70, 107). HMGB1 levels are increased in the kidney in sepsis, and therapeutic interventions that neutralize or inhibit HMGB1 reduce kidney injury and improve survival in models of sepsis and endotoxemia (4, 16, 19, 37, 52, 93, 108). Extracellular HMGB1 also is implicated in the pathogenesis of sterile kidney disorders, including diabetic nephropathy, ischemia-reperfusion injury, lupus nephritis, and posttransplant allograft rejection (4, 13, 48, 54, 58, 72, 78, 106, 111). HMGB1 thus represents a potential therapeutic target to improve kidney function in both infectious and noninfectious inflammatory disorders. The pathogenic effects of HMGB1 in the kidney are thought to involve its role as an extracellular mediator of proinflammatory responses that can lead to tubule and glomerular injury (4, 13, 21, 48, 58, 72, 73, 78, 106, 108). However, despite the broad interest in HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of kidney disease, the specific mechanisms by which HMGB1 influences kidney function remain poorly understood. Whether HMGB1 can act directly to alter the function of renal tubules, and the receptor signaling pathways that may be activated by HMGB1 in nephron segments, are undefined.

Recently, we demonstrated that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption by the medullary thick ascending limb (MTAL) and that the HMGB1-induced inhibition is mediated through a RAGE-dependent signaling pathway in the basolateral membrane (29). These studies provided the first evidence that extracellular HMGB1 acts directly to impair the transport function of renal tubules, identifying a new pathophysiological mechanism that can contribute to renal tubule dysfunction during sepsis and other inflammatory disorders. The direct action of HMGB1 to decrease HCO3− absorption has important implications for sepsis pathogenesis because it would impair the ability of the kidneys to correct metabolic acidosis that contributes to multiple organ dysfunction (7, 29, 47, 50, 81) and is associated with increased mortality in septic patients (32, 33, 51, 63). In addition, these studies uncovered a role for RAGE as a cell surface receptor that directly modulates renal epithelial transport and identified HMGB1-RAGE signaling as a potential therapeutic target to preserve or improve renal tubule function in sepsis and inflammatory diseases. At present, however, the intracellular signaling pathways that are activated through RAGE and that result in HMGB1-induced inhibition of HCO3− absorption in the MTAL are unknown.

The MTAL participates in acid-base homeostasis by reabsorbing most of the filtered HCO3− not reabsorbed by the proximal tubule (23, 34). Absorption of HCO3− by the MTAL depends on H+ secretion mediated by the apical membrane Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 (11, 23, 30, 104). The regulation of MTAL HCO3− absorption by a variety of physiological and pathophysiological factors is achieved through regulation of this exchanger (23, 30, 34, 98, 100, 103, 104). The basolateral Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 also is an important determinant of the rate of MTAL HCO3− absorption. In particular, inhibition of NHE1 results secondarily in inhibition of apical NHE3, thereby decreasing HCO3− absorption (25, 31, 96, 97). NHE1 modulates NHE3 activity by regulating the organization of the actin cytoskeleton (97). The rate of HCO3− absorption in the MTAL thus depends on a regulatory interaction between the basolateral and apical membrane Na+/H+ exchangers, whereby basolateral NHE1 enhances the activity of apical NHE3 (25, 26, 31, 96, 97). The transport mechanisms by which HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL are not known. Whether Na+/H+ exchange activity is regulated by HMGB1 or is a downstream target of RAGE signaling in renal tubule cells has not been determined.

In addition to HMGB1, absorption of HCO3− by the MTAL is inhibited by bacterial LPS (27, 100). Basolateral LPS inhibits HCO3− absorption through a TLR4-mediated ERK signaling pathway coupled primarily to inhibition of NHE3 (100). Of significance, the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 through RAGE is distinct from and additive to inhibition by LPS through TLR4 (29). These studies revealed a novel paradigm for sepsis-induced renal tubule dysfunction, whereby endogenous damage-associated molecules and exogenous pathogen-associated molecules function directly and independently to impair MTAL HCO3− absorption (29). Thus understanding the distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms by which HMGB1 and LPS inhibit HCO3− absorption in the MTAL may aid in identifying effective strategies to target the different pathways. At present, however, the specific intracellular signaling molecules that distinguish inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 from inhibition by LPS remain undefined.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the intracellular signaling and transport mechanisms by which HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL. The results indicate that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption through the activation of a RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 pathway coupled to inhibition of basolateral NHE1. These studies establish a role for Rho-ROCK signaling in mediating HMGB1-induced renal tubule dysfunction and identify NHE1 as a downstream target of HMGB1-induced RAGE signaling in the MTAL. The signaling and transport mechanisms through which HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption are distinct from those that mediate inhibition by basolateral LPS, which enables HMGB1 and LPS to act additively and independently to impair MTAL function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (50–90 g body wt) were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice deficient in MyD88 [B6.129P2(SJL)-Myd88tm1.1Defr/J; MyD88−/−] were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were 7 wk old. The animals were maintained under pathogen-free conditions in microisolator cages and received standard rodent chow (NIH 31 diet, Ziegler) and water up to the time of experiments. All protocols in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Texas Medical Branch.

Tubule perfusion and measurement of net HCO3− absorption.

MTALs were isolated and perfused in vitro as previously described (22, 29). Tubules were dissected from the inner stripe of the outer medulla at 10°C in control bath solution (see below), transferred to a bath chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope, and mounted on concentric glass pipettes for perfusion at 37°C. The tubules were perfused and bathed in control solution that contained (in mM) 146 Na+, 4 K+, 122 Cl−, 25 HCO3−, 2.0 Ca2+, 1.5 Mg2+, 2.0 phosphate, 1.2 SO42−-, 1.0 citrate, 2.0 lactate, and 5.5 glucose (equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.45 at 37°C). Solutions containing HMGB1 (1 μg/ml, purified human recombinant; Prospec), LPS (500 ng/ml, ultra pure Escherichia coli K12; InvivoGen), and other experimental agents were prepared as described (25, 29, 31, 96, 97, 100). The ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (Cayman Chemical) was prepared as a stock solution in DMSO and diluted into bath solution to a final concentration of 10 μM (DMSO 0.08% vol/vol). Rho Inhibitor I (CT04, Cytoskeleton) was diluted into the bath solution to a final concentration of 0.8 μg/ml. Rho Inhibitor I incorporates the exoenzyme C3 transferase, which specifically inactivates Rho-GTPases by ADP ribosylation on Asp41 in the effector binding region (1). Experimental agents were added to the bath solution as described in results. In one series of HCO3− transport experiments (see Fig. 7B), Na+ in the bath solution was replaced with N-methyl-d-glucammonium (NMDG+).

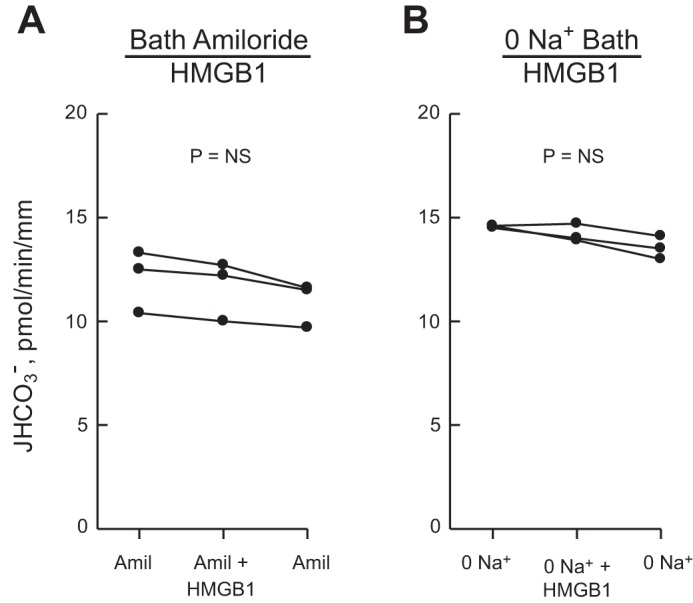

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is eliminated by inhibitors of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange. MTALs were studied with 10 μM amiloride in the bath (A) or in a Na+-free bath (B), conditions that inhibit basolateral Na+/H+ exchange (25, 31, 96). HMGB1 was then added to and removed from the bath solution. In B, Na+ in the bath was replaced with NMDG+; the lumen was perfused with control solution containing 146 mM Na+. JHCO3−, data points, lines, and P values are as in Fig. 1. Mean values are given in results.

The protocol for the study of transepithelial HCO3− absorption was as described (22, 27, 29). Tubules were equilibrated for 20–30 min at 37°C in the initial perfusion and bath solutions, and the luminal flow rate (normalized per unit tubule length) was adjusted to 1.5–1.8 nl·min−1·mm−1. One to three 10-min tubule fluid samples were then collected for each period (initial, experimental, and recovery). In all protocols, the lumen and bath solutions were identical in the initial and recovery periods. The tubules were allowed to reequilibrate for 5–10 min after an experimental agent was added to or removed from the bath solution. As described previously, bath exchanges to the HMGB1-containing solution in the experimental period and to the initial control solution in the recovery period were carried out manually, and tubule fluid samples in those periods were collected under stationary (no flow) bath conditions (29). This same protocol was used in experiments examining bath addition of LPS. For experiments involving treatment with Rho Inhibitor I (Fig. 3), a stationary bath was used in all periods; in the initial period, the tubules were bathed with Rho Inhibitor for 120 min, with the bath exchanged at 30- to 40-min intervals. Time control experiments were performed using an identical protocol (see Fig. 3C). As demonstrated previously, the bath exchange protocol has no effect on the HCO3− absorption rate (29). The absolute rate of HCO3− absorption (JHCO3−; pmol·min−1·mm−1) was calculated from the luminal flow rate and the difference between total CO2 concentrations measured in perfused and collected fluids (22). An average HCO3− absorption rate was calculated for each period studied in a given tubule. When repeat measurements were made with the same bath solution at the beginning and end of an experiment (initial and recovery periods), the values were averaged. Single tubule values are presented in the figures. Mean values ± SE (n = number of tubules) are presented in the text.

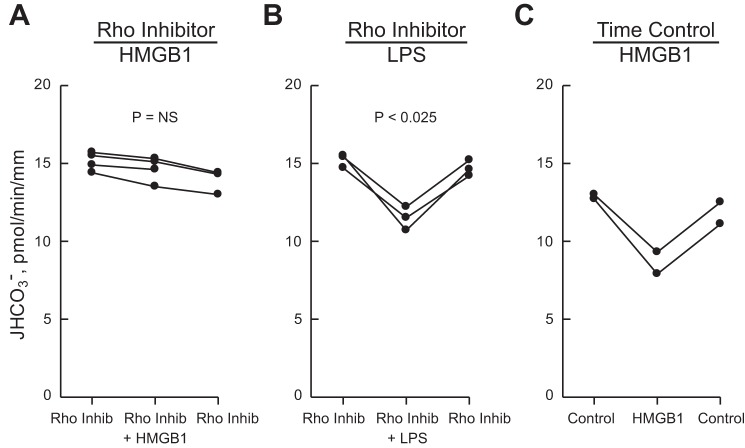

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is mediated by Rho. A and B: MTALs were bathed with Rho Inhibitor I (0.8 μg/ml) for 120 min, and then HMGB1 (A) or LPS (B) was added to and removed from the bath solution. C: time control experiments in which MTALs were bathed with control solution for 120 min, and then HMGB1 was added to and removed from the bath solution. Protocol details are provided in materials and methods. JHCO3−, data points, lines, and P values are as in Fig. 1. Mean values are given in results.

ROCK1 activity assay.

Activation of ROCK1 was evaluated using a previously described inner stripe of the outer medulla tissue preparation (24, 26, 100, 105). This preparation is highly enriched in MTALs and exhibits regulated changes in the expression and activity of receptor signaling proteins that accurately reproduce changes observed in the MTAL (24, 26, 98–101, 105). Following dissection at 4°C, inner stripe tissue was divided into four samples of equal amount and then incubated in vitro at 37°C in the same solutions used for HCO3− transport experiments. Solutions containing the RAGE antagonist FPS-ZM1 (EMD Millipore) were prepared as previously described (29). Specific protocols for incubations are given in results. After incubation, the tissue samples were homogenized on ice in ice-cold PBS and lysed for 2 h at 4°C in RIPA buffer, both with protease inhibitors (26). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and frozen at −70°C. ROCK1 activity was measured using ROCK Activity Immunoblot Kit (STA415, Cell Biolabs). In brief, samples containing 250 μg cell lysate were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-ROCK1 mAb (C8F7, Cell Signaling) bound to protein G magnetic beads (28). The immune complexes were washed and then incubated with kinase buffer/ATP solution (final volume 50 μl) containing recombinant myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) as a substrate following the manufacturer's protocol. This assay is based on the physiological action of ROCK to inactivate myosin phosphatase through the specific phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Thr696 (41, 95). The reaction was stopped after 45 min by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and phosphorylated MYPT1 was detected by immunoblotting using rabbit anti-phospho-MYPT1(Thr696) Ab (Cell Biolabs Kit). Immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence (Luminol Reagent, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) after incubation with HSP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary Ab. Phosphorylated MYPT1 was quantified by densitometry. Equal amounts of ROCK1 in immunoprecipitates were verified within experiments by immunoblotting with the same anti-ROCK1 mAb used for immunoprecipitation. Negative control assays were conducted in the absence of added lysate (without kinase); positive control reactions were run using active ROCK II.

RhoA activation assay.

Activation of RhoA was determined in the inner stripe of the outer medulla using a pull-down assay (Rho Activation Assay Biochem Kit BK036, Cytoskeleton). This assay quantifies Rho activation using the Rho binding domain (RBD) of the Rho effector protein rhotekin, which specifically binds the active (GTP-bound) form of Rho (41). Inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37°C in the absence and presence of HMGB1 for 3–15 min. The tissue was then rapidly washed and homogenized in ice-cold kit-provided cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation, snap frozen, and stored at −70°C. For the Rho assay, samples (500 μg) for each condition were incubated with rhotekin-RBD Sepharose beads for 60 min at 4°C following the manufacturer's instructions. Beads were collected by centrifugation, washed, resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and boiled. The amount of activated RhoA pulled down by the beads (RhoA-GTP) was determined by immunoblotting using a kit-provided monoclonal anti-RhoA Ab. Immunoreactive bands were detected after secondary Ab binding by chemiluminescence, and RhoA-GTP levels were quantified by densitometry. Equal amounts of total RhoA in sample lysates were verified within experiments by immunoblotting. Positive and negative control reactions were run on total cell lysates loaded with GTPγS (+) or GDP (−).

Measurement of intracellular pH and basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity.

Intracellular pH (pHi) was measured in isolated, perfused MTALs by use of the pH-sensitive dye BCECF and a spectrofluorometer coupled to the perfusion apparatus, as previously described (96, 102, 103). MTALs were perfused and bathed in Na+-free HEPES-buffered solution that contained (in mM) 145 NMDG+, 4 K+, 147 Cl−, 2.0 Ca2+, 1.5 Mg2+, 1.0 phosphate, 1.0 SO42−, 1.0 citrate, 2.0 lactate, 5.5 glucose, and 5 HEPES (equilibrated with 100% O2; titrated to pH 7.4). Basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity was determined by measurement of the initial rate of pHi increase after addition of 145 mM Na+ to the bath solution (Na+ replaced NMDG+), the intracellular buffering power, and cell volume, as described (26, 96). The lumen solution contained ethylisopropyl amiloride (EIPA; 50 μM) to eliminate any contribution of apical Na+/H+ exchange to the Na+-induced changes in pHi. The Na+-dependent pHi recovery is inhibited ≥90% by bath EIPA (50 μM). Experimental agents were added to the bath solution as described in results.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy.

MTALs were studied by confocal microscopy as previously described (26, 97, 100). Rat MTALs were microdissected and mounted on Cell-Tak-coated coverslips at 10°C. The tubules were then incubated in the absence and presence of HMGB1 for 15 min at 37°C in a flowing bath using the same solutions as in HCO3− transport experiments. The specific protocols for incubation are given in results. Following incubation, the tubules were fixed and permeabilized in cold acetone and held at −20°C for 10 min. The tubules were incubated in Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature, washed in PBS, and blocked in 10% normal donkey serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The tubules were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-phospho-MYPT1(Thr696) antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), washed, and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:100; Invitrogen) in blocking buffer. Fluorescence staining was examined using a Zeiss laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM510 UV META), as described (26, 97, 100). Tubules were imaged longitudinally, and z-axis optical sections (0.4 μm) were obtained through a plane at the center of the tubule, which provides a cross-sectional view of cells in the lateral tubule walls. For individual experiments, tubules from the same kidney for each experimental condition were fixed and stained identically and imaged in a single session at identical settings of illumination, gain, and exposure time. Fluorescence intensity of p-MYPT1(Thr696) staining was quantified by two-dimensional image analysis as previously described (99, 100).

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE. Differences between means were evaluated using Student's t-test for paired data or analysis of variance with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons, as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL.

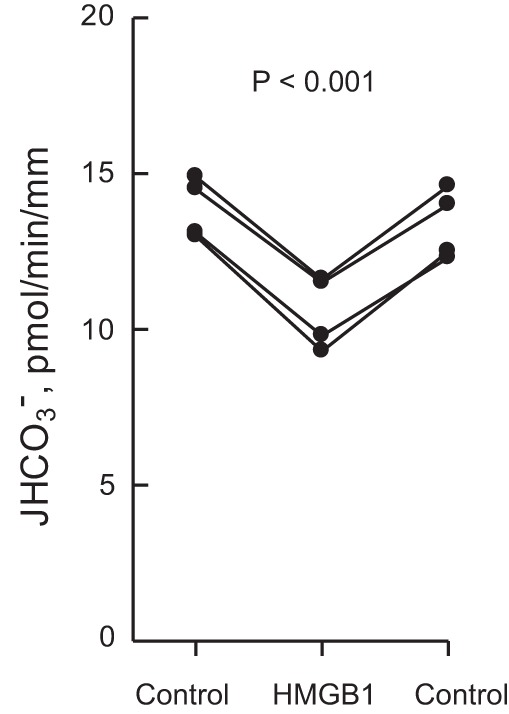

Adding HMGB1 (1 μg/ml) to the bath decreased HCO3− absorption by 23% (from 13.7 ± 0.5 to 10.5 ± 0.6 pmol·min−1·mm−1) in isolated, perfused MTALs from rats (Fig. 1). The inhibition by HMGB1 is observed within 15 min, sustained for up to 60 min, and reversible. These data confirm previous results demonstrating that basolateral HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in rat and mouse MTALs through a RAGE-dependent pathway (29).

Fig. 1.

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) inhibits HCO3− absorption in the medullary thick ascending limb (MTAL). MTALs from rats were isolated and perfused in vitro in control solution, and then HMGB1 (1 μg/ml) was added to and removed from the bath solution. Absolute rates of HCO3− absorption (JHCO3−) were measured as described in materials and methods. Data points are average values for single tubules. Lines connect paired measurements made in the same tubule. The P value is for paired t-test. Mean values are given in results.

ROCK inhibitor eliminates inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1.

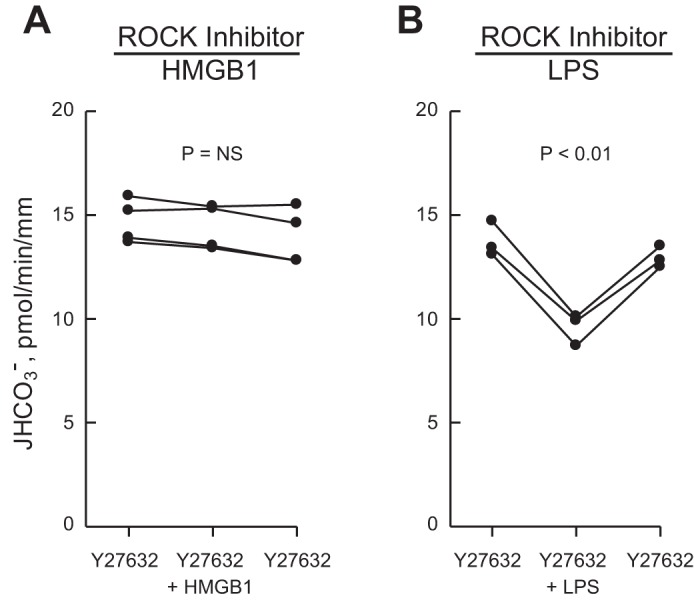

The intracellular signaling pathways activated by HMGB1 through RAGE in renal tubules are undefined. Previously, we demonstrated that the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 in the MTAL is not mediated through ERK (29). Further experiments were carried out to examine additional signaling pathways that mediate RAGE-induced cell responses in other systems. To examine the role of the serine/threonine kinase ROCK in inhibition by HMGB1, we examined the effects of the selective ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (90). As shown in Fig. 2A, the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 was eliminated in MTALs bathed with Y27632 (14.4 ± 0.5 pmol·min−1·mm−1, Y27632 vs. 14.4 ± 0.5, Y27632+HMGB1). Y27632 also eliminates inhibition by HMGB1 in MTALs from mice (not shown). In contrast, the ROCK inhibitor did not prevent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath LPS (13.4 ± 0.4 pmol·min−1·mm−1, Y27632 vs. 9.6 ± 0.4, Y27632+LPS) (Fig. 2B), demonstrating specificity of Y27632's inhibitory effect and extending our previous results showing that HMGB1 and LPS inhibit HCO3− absorption through different pathways (29). These results support an essential role for ROCK in mediating RAGE-dependent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1.

Fig. 2.

Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor eliminates inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 but not by LPS. MTALs were bathed with 10 μM Y27632, and then HMGB1 (A) or LPS (B) was added to and removed from the bath solution. JHCO3−, data points, lines, and P values are as in Fig. 1. NS, not significant. Mean values are given in results.

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is mediated through Rho.

To define further the signaling pathway responsible for inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1, we examined the role of the small GTP-binding protein Rho, the primary upstream activator of ROCK (41, 76). MTALs were bathed with Rho Inhibitor 1, which specifically inhibits Rho proteins by ADP ribosylation (see materials and methods). As shown in Fig. 3A, the effect of HMGB1 to inhibit HCO3− absorption was eliminated by the Rho inhibitor (14.6 ± 0.4 pmol·min−1·mm−1, Rho inhibitor vs. 14.6 ± 0.4, Rho inhibitor+HMGB1). The basal rate of HCO3− absorption in MTALs treated with the Rho inhibitor was similar to that measured in the absence of the inhibitor (Fig. 1). In addition, similar to results obtained with the ROCK inhibitor (Fig. 2B), the Rho inhibitor did not prevent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath LPS (15.0 ± 0.2 pmol·min−1·mm−1, Rho inhibitor vs. 11.5 ± 0.4, Rho inhibitor+LPS) (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, in time control experiments using an identical protocol without the Rho inhibitor, HMGB1 decreased HCO3− absorption by 31% (Fig. 3C). Thus the effect of the Rho inhibitor to block inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is selective and is not due to a nonspecific effect of the inhibitor or the experimental protocol on the tubule cells. These results support the view that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through the activation of a Rho-ROCK signaling pathway.

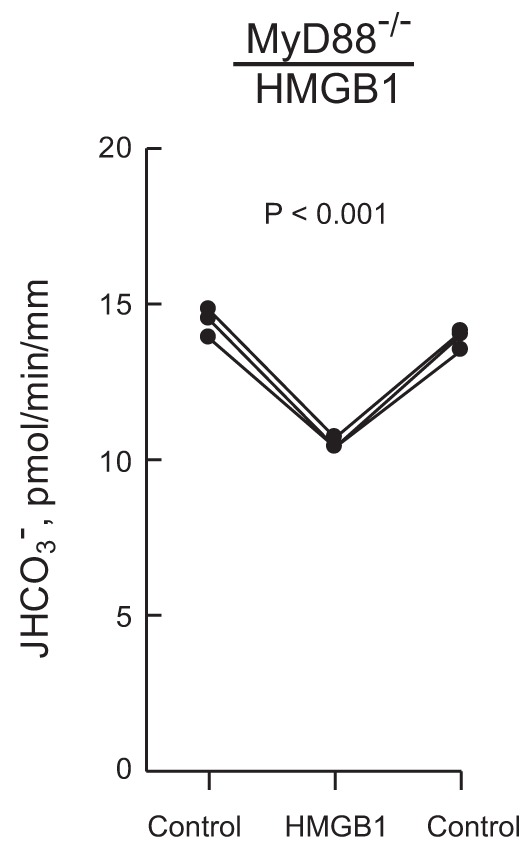

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is not mediated through MyD88.

In some systems, RAGE interacts with the intracellular adaptor protein MyD88 to activate downstream signaling pathways (40, 85). We have shown that MyD88 mediates the TLR4-dependent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by basolateral LPS (100). Therefore, we tested whether the HMGB1-RAGE and LPS-TLR4 pathways that inhibit HCO3− absorption in the MTAL may share MyD88 as a common signaling component. As shown in Fig. 4, adding HMGB1 to the bath decreased HCO3− absorption by 26% (from 14.2 ± 0.2 to 10.5 ± 0.1 pmol·min−1·mm−1) in MTALs from MyD88-deficient mice. This decrease is similar to that induced by HMGB1 in MTALs from wild-type controls (C57BL/6J) (29). These results are in direct contrast to the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath LPS, which is eliminated in MyD88-/− MTALs (100). These results show that the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 through RAGE is not mediated by MyD88 and provide further evidence that the basolateral HMGB1 and LPS signaling pathways that inhibit HCO3− absorption in the MTAL are distinct.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is not mediated through MyD88. MTALs from MyD88-deficient (MyD88−/−) mice were perfused in vitro under control conditions, and then HMGB1 was added to and removed from the bath solution. JHCO3−, data points, lines, and P values are as in Fig. 1. Mean values are given in results.

HMGB1 increases ROCK1 activity through a RAGE- and Rho-dependent pathway.

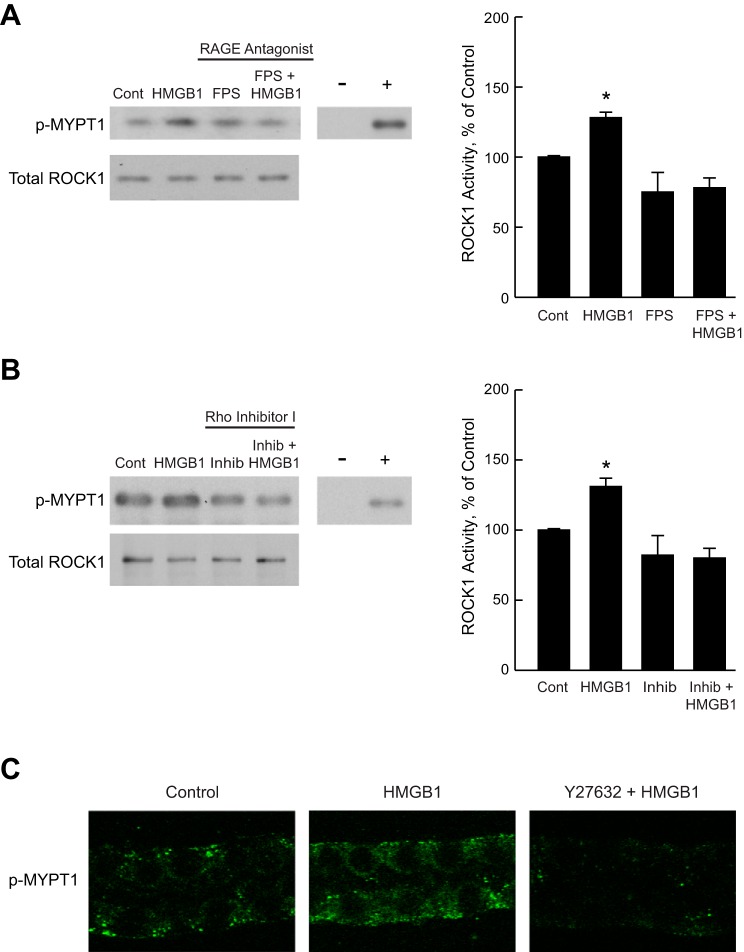

To determine directly whether HMGB1 activates ROCK, ROCK1 activity was examined in the inner stripe of the outer medulla dissected from rat kidneys. This preparation has been shown previously to accurately reproduce regulated changes in the activity of signaling proteins in the MTAL (24, 26, 98–100, 105). Inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro in the absence and presence of HMGB1 for 15 min, and then ROCK1 activity was determined using an immunoprecipitation kinase assay that measures phosphorylation of MYPT1 (see materials and methods). As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, HMGB1 increased ROCK1 activity 1.3 ± 0.03-fold without a change in total ROCK1 level. The activation of ROCK1 by HMGB1 was blocked by pretreatment with the RAGE antagonist FPS-ZM1 (Fig. 5A) or with Rho Inhibitor I (Fig. 5B). These results demonstrate that HMGB1 increases ROCK1 activity and show that this activation is mediated through RAGE and Rho.

Fig. 5.

HMGB1 activates ROCK1 through RAGE and Rho. A and B: inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37°C in the absence (Control) and presence of the RAGE antagonist FPS-ZM1 for 15 min (A) or Rho Inhibitor I for 120 min (B), and then treated with HMGB1 for 15 min. ROCK1 activity was determined in cell lysates by immunoprecipitation kinase assay using recombinant MYPT1 as a substrate (see materials and methods). Substrate phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-phospho-MYPT1(Thr696) antibody (p-MYPT1). Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-ROCK1 antibody for total ROCK1 levels. Negative control (−, without kinase) and positive control (+, active ROCK II) lanes are shown to verify assay specificity. Experimental and −/+ control lanes are from the same gel. Blots are representative of 4 independent experiments of each type. ROCK1 activity was determined by densitometric analysis of phosphorylated MYPT1 and expressed as a percentage of the control value measured in the same experiment. Bars are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. Control (ANOVA). C: microdissected MTALs were incubated in vitro at 37°C under control conditions and in the presence of HMGB1 or Y27632+HMGB1. Treatment with HMGB1 was for 15 min. Tubules were treated with Y27632 for 15 min before HMGB1 addition. The tubules were fixed and stained with anti-phospho-MYPT1(Thr696) antibody (p-MYPT1) and analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence as described in materials and methods. HMGB1 increased p-MYPT1 labeling, and this increase was eliminated by Y27632. Quantification of p-MYPT1 fluorescence intensity was as described in materials and methods and is given in results. Images are representative of at least 7 tubules of each type.

To confirm directly that HMGB1 activates ROCK in the MTAL, ROCK activity was assessed in microdissected MTALs by examining phosphorylation of endogenous MYPT1. MTALs were incubated in vitro in the absence and presence of HMGB1 for 15 min, stained with anti-phospho-MYPT1 antibody (p-MYPT1), and then analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence (see materials and methods). Stimulation with HMGB1 increased p-MYPT1 staining 1.4 ± 0.1-fold (P < 0.05), and the increase in MYPT1 phosphorylation was eliminated by the ROCK inhibitor (Fig. 5C). These results confirm that HMGB1 activates ROCK in the MTAL and, together with the preceding activity assay experiments, support the view that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through a RAGE-Rho-ROCK1 signaling pathway.

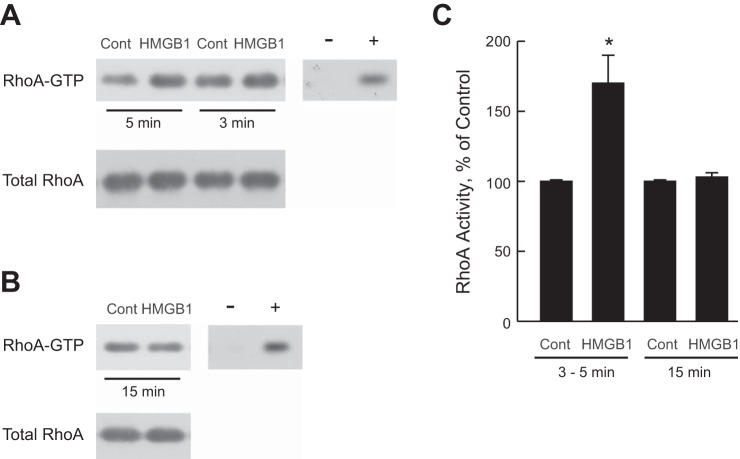

HMGB1 activates RhoA.

Further studies were conducted to examine directly whether Rho is activated by HMGB1. Inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37°C in the absence and presence of HMGB1 for 3, 5, or 15 min. Early time points were studied in this protocol based on studies in other systems showing that Rho proteins can be activated very rapidly and transiently upon stimulation (46, 57, 92). RhoA activity was determined in a pull-down assay using rhotekin-RBD-coated beads that specifically bind the active (GTP bound) form of RhoA (see materials and methods). As shown in Fig. 6, A and C, treatment with HMGB1 for 3–5 min increased RhoA activity 1.7 ± 0.2-fold. The increase in RhoA activity was not detected at 15 min (Fig. 6, B and C), indicating that the activation of RhoA by HMGB1 occurs in a time-dependent manner. These results establish directly that HMGB1 induces rapid activation of RhoA and, together with the results in Fig. 5B, support RhoA as the upstream activator of ROCK1 that mediates inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 in the MTAL.

Fig. 6.

HMGB1 activates RhoA. A and B: inner stripe tissue was incubated in vitro at 37°C in the absence (Control) and presence of HMGB1 for the indicated times. RhoA activity was measured in cell lysates using a rotekin-RBD pull-down assay in which levels of activated RhoA (RhoA-GTP) are measured by immunoblotting with anti-RhoA Ab (see materials and methods). Total RhoA level was determined in a portion of each lysate. Negative and positive control lanes indicate assay of cell lysates loaded with GDP (−) or GTPγS (+). Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments of each type. C: activity of RhoA was determined for experiments in A and B by densitometric analysis of RhoA-GTP and expressed as a percentage of the control value measured in the same experiment. Results for 3- and 5-min HMGB1 treatment are combined. Bars are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is eliminated by inhibitors of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange.

The Rho-ROCK pathway regulates NHE1 activity in other systems (12, 88, 91), and we have shown previously that inhibiting basolateral NHE1 decreases HCO3− absorption in the MTAL (25, 31, 96, 97). To test whether NHE1 is involved in inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1, we examined the effects of HMGB1 in the presence of 10 μM bath amiloride and in the absence of bath Na+, two conditions that inhibit basolateral Na+/H+ exchange and selectively prevent inhibition of HCO3− absorption mediated through NHE1 (25, 31, 96, 97). The results in Fig. 7 show that the effect of HMGB1 to inhibit HCO3− absorption was eliminated in tubules bathed with amiloride (12.5 ± 0.4 pmol·min−1·mm−1, amiloride vs. 12.4 ± 0.5, amiloride+HMGB1), or studied in a Na+-free bath (14.1 ± 0.2 pmol·min−1·mm−1, 0 Na+ vs. 14.2 ± 0.3, 0 Na++HMGB1). These results extend our previous observations (29) and support the view that the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is mediated through inhibition of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange.

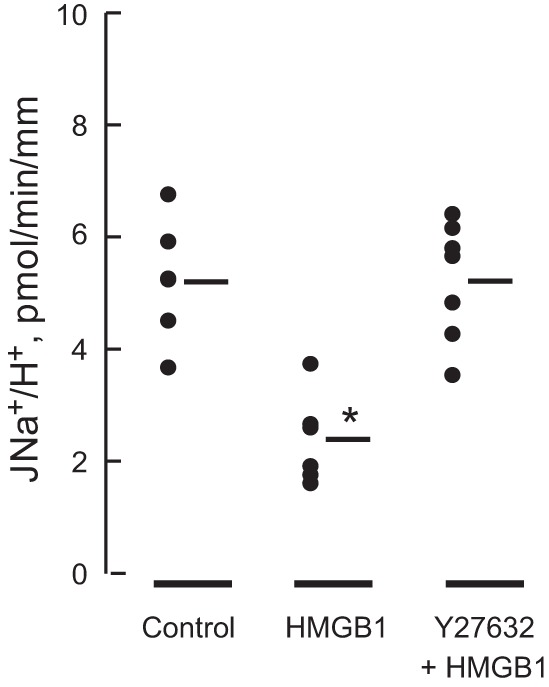

HMGB1 inhibits basolateral Na+/H+ exchange through ROCK.

Based on the preceding results, further studies were carried out to examine directly whether HMGB1 affects basolateral Na+/H+ exchange in the MTAL. The effect of HMGB1 on basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity was examined in the absence and presence of the ROCK inhibitor Y27632. As shown in Fig. 8, HMGB1 decreased the basolateral Na+/H+ exchange rate by 54% (5.2 ± 0.4, control vs. 2.4 ± 0.3 pmol·min−1·mm−1, HMGB1). The effect of HMGB1 to decrease basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity was eliminated in tubules bathed with the ROCK inhibitor (5.2 ± 0.4 pmol·min−1·mm−1, Y27632+HMGB1) (Fig. 8). These results demonstrate that HMGB1 decreases basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity in the MTAL through a ROCK-dependent pathway and support further the conclusion that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption through primary inhibition of basolateral NHE1.

Fig. 8.

HMGB1 inhibits basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity through a ROCK-dependent pathway. MTALs were perfused in vitro under control conditions and with HMGB1 or Y27632+HMGB1 in the bath solution. Treatment with HMGB1 was for 10 min. Tubules were bathed with Y27632 for 10 min before addition of HMGB1. Basolateral Na+/H+ exchange rates (JNa+/H+) were determined from initial rates of intracellular pH (pHi) increase in response to bath Na+ addition (see materials and methods). Data points are for individual tubules. Mean values are given in results. Initial pHi was 6.75 ± 0.03 and did not differ in the 3 groups. The number of tubules is 6 for Control, 6 for HMGB1, and 7 for Y27632+HMGB1. *P < 0.05 vs. Control or Y27632+HMGB1 (ANOVA).

Inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is blocked by the actin cytoskeleton modifier jasplakinolide.

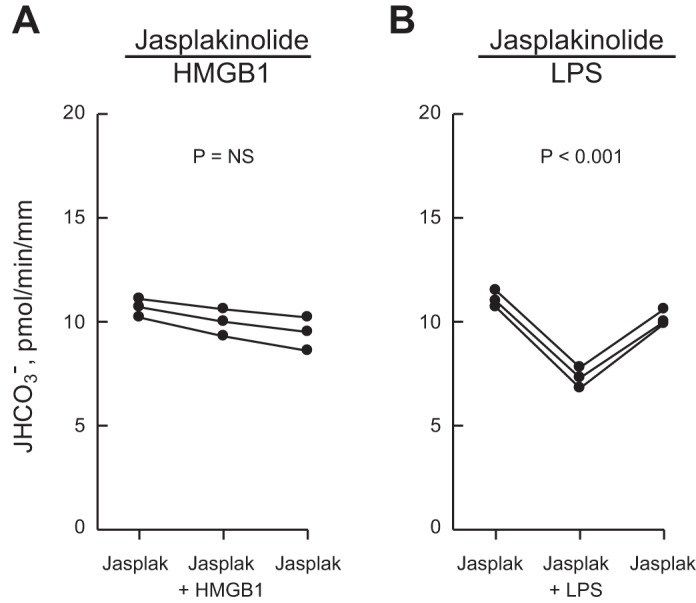

We have shown previously that inhibiting NHE1 decreases HCO3− absorption in the MTAL by inducing actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3 (31, 96, 97). To test further whether this regulatory mechanism mediates inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1, we examined the effects of jasplakinolide, an F-actin stabilizer that selectively blocks inhibition of HCO3− absorption mediated through NHE1 in the MTAL (15, 97). As shown in Fig. 9A, HMGB1 had no effect on HCO3− absorption in MTALs bathed with jasplakinolide (10.1 ± 0.3, jasplakinolide vs. 10.0 ± 0.4 pmol·min−1·mm−1, jasplakinolide+HMGB1). In contrast, jasplakinolide did not prevent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath LPS (10.6 ± 0.2, jasplakinolide vs. 7.3 ± 0.3 pmol·min−1·mm−1, jasplakinolide+ LPS) (Fig. 9B), which decreases HCO3− absorption through primary inhibition of NHE3, independently of NHE1 (100). These results indicate that inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 involves the actin cytoskeleton and extend our previous studies demonstrating that jasplakinolide selectively blocks inhibition of HCO3− absorption by factors that act through NHE1 (31, 97).

Fig. 9.

Jasplakinolide prevents inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 but not by LPS. MTALs were bathed with 0.05 μM jasplakinolide for 35–50 min, and then HMGB1 (A) or LPS (B) was added to and removed from the bath solution. JHCO3−, data points, lines, and P values are as in Fig. 1. Mean values are given in results.

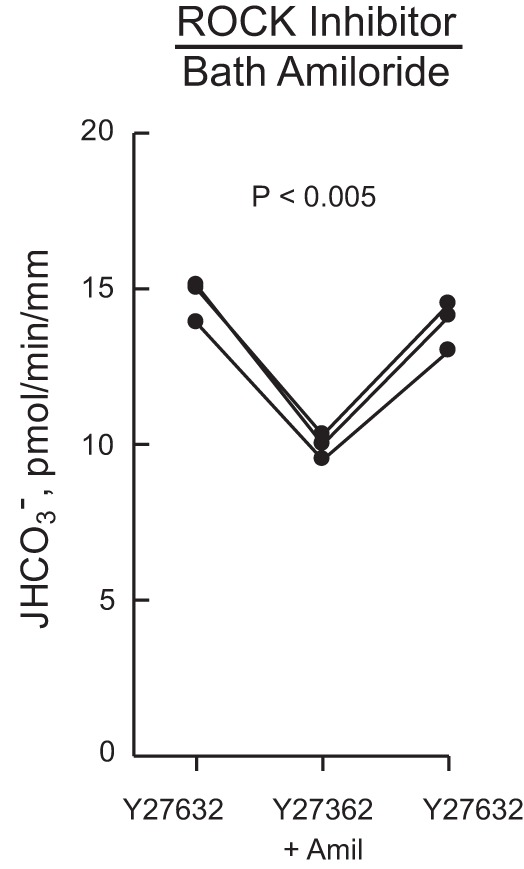

ROCK inhibitor does not affect inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath amiloride.

The preceding results support a mechanism whereby HMGB1 inhibits NHE1 through ROCK, which induces actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3 and HCO3− absorption (31, 96, 97). An additional mechanism by which ROCK signaling could affect HCO3− absorption in the MTAL is by altering the regulatory interaction between the basolateral NHE1 and apical NHE3 Na+/H+ exchangers. To test this, we took advantage of our previous finding that the cytoskeleton-mediated interaction between the exchangers and the resulting inhibition of HCO3− absorption can be induced directly by inhibiting basolateral NHE1 with bath amiloride (25, 31, 96, 97). As shown in Fig. 10, bath addition of amiloride decreased HCO3− absorption by 30% (from 14.3 ± 0.4 to 10.0 ± 0.2 pmol·min−1·mm−1) in MTALs bathed with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632. This decrease is similar to that induced by bath amiloride in the absence of the inhibitor (26, 97). These results indicate that ROCK is not involved in mediating the regulatory interaction between the basolateral NHE1 and apical NHE3 Na+/H+ exchangers and support further the view that the role of the RhoA-ROCK1 signaling pathway in inhibition of HCO3− absorption is to mediate HMGB1-induced inhibition of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange.

Fig. 10.

ROCK inhibitor does not prevent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by bath amiloride. MTALs were bathed with Y27632, and then amiloride (10 μM) was added to and removed from the bath solution. JHCO3−, data points, lines, and P values are as in Fig. 1. Mean values are given in results.

DISCUSSION

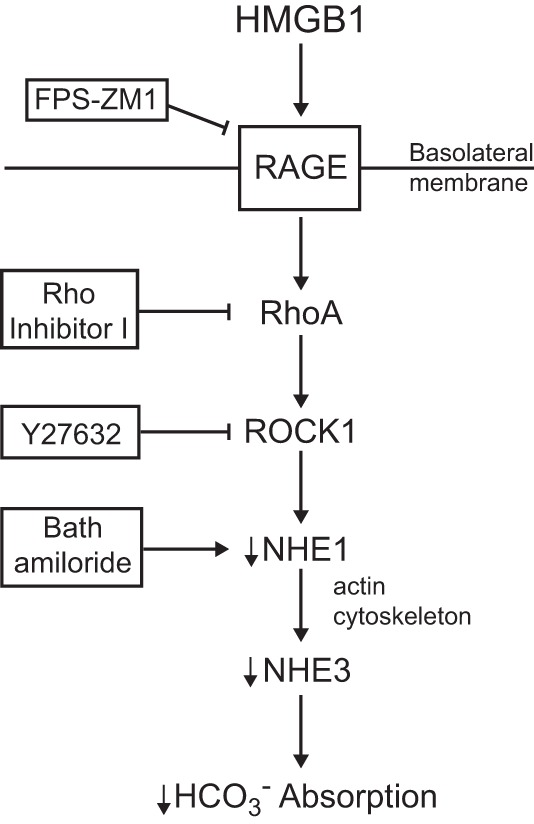

HMGB1 released from cells into the extracellular fluid is implicated in the pathogenesis of kidney dysfunction in a variety of inflammatory disorders, including sepsis, diabetic nephropathy, lupus nephritis, and ischemia-reperfusion injury (4, 13, 16, 19, 37, 48, 52, 54, 58, 72, 78, 106, 108, 111). The specific mechanisms by which HMGB1 impairs kidney function are poorly understood but are thought to involve its role in activating the release of cytokines and other proinflammatory mediators (4, 13, 21, 48, 58, 72, 78, 106, 108, 111). Recently, we demonstrated that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through the activation of a RAGE signaling pathway (29). These studies established that extracellular HMGB1 can act directly to impair the transport function of renal tubules, independently of its effects on proinflammatory mediators. The current study was designed to identify the intracellular signaling and transport mechanisms that mediate the inhibition by HMGB1. Our results show that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through a RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 signaling pathway coupled to inhibition of the basolateral Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 (Fig. 11). These results identify the RhoA-ROCK1 pathway as a signaling intermediate that couples RAGE directly to the modulation of renal tubule transport. In addition, we show that the receptor signaling and transport mechanisms that mediate inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 are distinct from those that mediate inhibition by basolateral LPS, which would enable these pathogenic stimuli to act directly and independently during sepsis to impair the transport function of the MTAL.

Fig. 11.

Model for inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 in the MTAL. Extracellular HMGB1 activates a basolateral RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 signaling pathway coupled to inhibition of the basolateral Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1. Inhibition of NHE1 results secondarily in inhibition of apical NHE3 through actin cytoskeleton remodeling, thereby decreasing HCO3− absorption (25, 31, 96, 97). Arrows do not necessarily imply direct relationships; regulatory steps may involve additional signaling components. See text for details.

We previously demonstrated that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through activation of RAGE in the basolateral membrane. This conclusion is supported by several lines of evidence, including elimination of HMGB1's inhibitory effect by a neutralizing anti-RAGE antibody in the bath solution (29). These studies provided the first evidence that RAGE functions as a receptor for HMGB1 in renal tubules and that intracellular signals transduced by RAGE directly modulate renal epithelial transport. In the current study, we show that the RAGE-dependent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is mediated through the downstream activation of RhoA-ROCK1. ROCK1 is a ubiquitously expressed serine/threonine kinase that binds GTP-bound active RhoA and functions as an important effector of RhoA signaling (3, 41, 76). The Rho-ROCK pathway controls the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and plays an important role in the regulation of fundamental cell processes including stress fiber formation, adhesion, proliferation, migration, survival, and proinflammatory gene expression (3, 41, 76). RAGE-mediated activation of Rho-ROCK has been implicated in pathogenic processes such as atherogenesis and microvascular hyperpermeability (9, 14, 35), and inhibition of Rho/ROCK signaling has been reported to convey protection against renal fibrosis and inflammation in models of diabetic nephropathy, ureteral obstruction, and drug-induced nephrotoxicity (41, 45, 64, 69, 75). The results of the present study show that 1) HMGB1 increases RhoA and ROCK1 activity in the MTAL, 2) the activation of ROCK1 by HMGB1 depends on RAGE and Rho, and 3) inhibitors of RhoA and ROCK1 block the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1. These results support a mechanism by which ROCK1 functions downstream of RAGE and RhoA to mediate HMGB1-induced inhibition of HCO3− absorption. In addition, they raise the possibility that activation of RAGE could alter other renal tubule transport processes that are regulated through Rho and ROCK, such as aquaporin-2 trafficking, exocytosis and activation of NHE3, and vacuolar H+-ATPase recycling (83, 86, 109). Of significance, our results show that the effect of HMGB1 to impair HCO3− absorption in the MTAL is prevented by specific inhibitors of RAGE (29), Rho, or ROCK, identifying multiple sites within the HMGB1-induced signaling pathway as potential targets to preserve MTAL function during inflammatory disorders.

The molecular mechanisms by which RAGE stimulates RhoA-ROCK1 in the MTAL remain to be determined. RAGE is a cell surface receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily involved in the recognition of endogenous molecules released from cells in response to infection or injury, including HMGB1, advanced glycation end products, and certain S100/calgranulins (43, 60, 74). Activation of RAGE by its ligands stimulates innate immune and inflammatory responses (43, 60, 74), and RAGE has been implicated in the pathogenesis of kidney dysfunction in multiple disorders, including sepsis, diabetes, ischemia-reperfusion, lupus nephritis, polycystic kidney disease, and renal cell carcinoma (17, 37, 53, 67, 75, 78, 87). Full-length RAGE is composed of three major domains: an extracellular domain that contains the V and C1 regions that bind HMGB1, a single transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain (43, 61, 85). The cytoplasmic domain is essential for downstream signal transduction; however, it lacks endogenous tyrosine kinase activity or other known signaling motifs and therefore requires interaction with intracellular effector molecules to trigger signaling events (36, 38–40, 43, 74). In some systems, RAGE activates cell signals through the adaptor protein MyD88 (40, 85). MyD88 is recruited by Toll-like receptors to activate downstream signaling pathways (42), and we have shown that MyD88 mediates TLR4-dependent inhibition of HCO3− absorption by LPS in the MTAL (100). In contrast, our current results show that the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is fully preserved in MTALs from MyD88−/− mice, indicating that an effector molecule other than MyD88 must mediate the RAGE-induced transport inhibition. Another adaptor protein involved in RAGE signaling is diaphanous-1 (Dia1), a member of the formin protein family that interacts with Rho GTPases to regulate the actin cytoskeleton (49, 85). The RAGE cytoplasmic domain can interact with Dia1 (38), and Dia1 was reported to mediate RAGE-induced activation of Rac-1 and Cdc42 in glioma cells (38) and RhoA-ROCK1 in microglia (9). At present, the functions of Dia1 in the kidney are not known; however, in preliminary studies we found that Dia1 is expressed in the inner stripe of the outer medulla of both rat and mouse kidneys (Watts BA and Good DW, unpublished observations). Thus the possible role of Dia1 in mediating RAGE-dependent activation of RhoA-ROCK1 and inhibition of HCO3− absorption in the MTAL will be an important area for future investigation.

The Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE1 is expressed ubiquitously in the plasma membrane of nonpolarized cells and in the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells, where it plays essential roles in a variety of cell processes, including intracellular pH and cell volume homeostasis, proliferation, survival, and migration (18, 55, 66). In the MTAL, we have identified an important role for NHE1 in the regulation of transcellular HCO3− absorption. In particular, inhibiting NHE1 induces actin cytoskeleton remodeling that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3, thereby decreasing HCO3− absorption (25, 26, 31, 96, 97). The results of the current study indicate that HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL by inhibiting NHE1 through a RAGE-ROCK signaling pathway. This conclusion is supported by several lines of evidence: 1) the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 is eliminated by bath amiloride or a zero Na+ bath, two different conditions that inhibit basolateral Na+/H+ exchange and specifically prevent inhibition of HCO3− absorption mediated through NHE1 (25, 31, 96, 97); 2) inhibition by HMGB1 is eliminated by the F-actin stabilizer jasplakinolide, which selectively blocks inhibition of HCO3− absorption by factors that inhibit NHE1 but not by factors that primarily inhibit NHE3 (97). This specificity of jasplakinolide's actions was confirmed further in the present study, in which jasplakinolide eliminated NHE1-mediated inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 but had no effect on inhibition by bath LPS, which primarily inhibits NHE3 (100); 3) HMGB1 directly inhibits basolateral Na+/H+ exchange activity in the MTAL; and 4) both the effects of HMGB1 to inhibit basolateral Na+/H+ exchange and to decrease HCO3− absorption are mediated through ROCK activation. HMGB1 inhibits NHE1 when exchanger activity is studied independently of other transporters and in the absence of a change in the driving force for the exchanger, indicating that the HMGB1-induced ROCK pathway is coupled primarily to inhibition of NHE1. These studies show that NHE1 is a downstream target of HMGB1-induced RAGE signaling in renal tubule cells and that HMGB1 impairs the ability of the MTAL to absorb HCO3− through inhibition of this exchanger. NHE1 is expressed in the basolateral membrane of virtually all nephron segments (10, 31, 71). Our findings raise the possibility that HMGB1 released extracellularly during sepsis and inflammatory kidney diseases could adversely affect multiple functions in renal tubule cells that depend on NHE1, including pHi and cell volume regulation and cell survival (68). Moreover, NHE1 has been ascribed a role in a variety of immune and inflammatory responses, including cytokine and chemokine release, neutrophil activation, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and proliferation (18, 50, 82). Whether NHE1 may play a role in mediating effects of HMGB1 and RAGE on these immune responses remains to be determined.

NHE1 is regulated by diverse extracellular stimuli such as growth factors, hormones, extracellular matrix proteins, and osmotic stress (55, 66). This regulation involves multiple mechanisms, including phosphorylation of the exchanger by various kinases, the binding of regulatory proteins, and structural interactions of NHE1 with the actin cytoskeleton (55, 66, 68). Previous studies have reported regulation of NHE1 by ROCK. In contrast to its effect to inhibit NHE1 in the MTAL, activation of RhoA-ROCK signaling has been shown to increase NHE1 activity in other systems, including fibroblasts, breast tumor cells, and pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (12, 62, 88, 91). This stimulation involved phosphorylation of NHE1 by ROCK1 (88). The specific mechanisms by which RhoA-ROCK1 inhibits NHE1 in the MTAL remain to be determined. However, the different regulatory effects of RhoA-ROCK1 on NHE1 activity are similar to results reported for other signaling pathways, notably ERK and Akt, which have been shown to stimulate or inhibit NHE1 in different systems (56, 66, 84, 99, 105). It is possible that stimulation of ROCK1 leads to inhibition of NHE1 in the MTAL through activation of downstream targets, phosphorylation events, or interactions with accessory proteins that differ from those in other cell types. Alternatively, ROCK-induced regulation of NHE1 may be influenced by the specific upstream receptor pathway. For example, the effect of HMGB1 to inhibit NHE1 in the MTAL may involve interactions of RhoA-ROCK with other RAGE-induced signaling proteins such as Dia1. The functional consequence of ROCK-induced inhibition of NHE1 is to decrease HCO3− absorption through NHE1-induced actin cytoskeleton reorganization that secondarily inhibits apical NHE3 (31, 96, 97). Previous studies in fibroblasts have shown that NHE1 and RhoA-ROCK1 can interact to regulate actin cytoskeleton organization (88). In the MTAL, we found that ROCK mediates HMGB1-induced inhibition of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange (Fig. 8), but that activation of ROCK is not involved in mediating the cytoskeleton-dependent regulatory interaction between the basolateral and apical Na+/H+ exchangers (Fig. 10). Thus our data support the view that the primary role of the RhoA-ROCK1 pathway in inhibition of HCO3− absorption is to mediate HMGB1-induced inhibition of NHE1 (Fig. 11), not to mediate the NHE1-induced cytoskeleton remodeling that inhibits NHE3 (31, 96, 97).

In addition to NHE1, the Rho-Rock pathway has been reported to regulate NHE3. Treatment with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 decreased apical Na+/H+ activity in isolated proximal convoluted tubules from rats (62), and Rho-GTPase activity enhanced apical NHE3 accumulation in transfected renal epithelial cells (2). In contrast, in a proximal tubule cell line (OKP), inhibiting ROCK with Y27632 had no effect on basal NHE3 activity; however, Rho-ROCK activity contributed to acid-induced increases in apical NHE3 exocytosis and transport activity (109). In the MTAL, we found that the basal rate of HCO3− absorption was similar in tubules studied in the absence and presence of Rho or ROCK inhibitors (Figs. 1–3). In addition, the RhoA-ROCK1-induced inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 was dependent on primary inhibition of basolateral Na+/H+ exchange. Thus our results suggest that Rho-ROCK signaling is not an important determinant of basal Na+/H+ exchange activity in the MTAL under the conditions of our experiments and provide no evidence that RhoA-ROCK1 signaling is coupled primarily to regulation of NHE3. As discussed above, the activation of RhoA-ROCK1 by HMGB1 decreases apical NHE3 activity and HCO3− absorption in the MTAL secondarily through inhibition of basolateral NHE1. The differing dependence of NHE3 activity on Rho-ROCK signaling may reflect differences in the extent to which apical membrane recycling contributes to NHE3 regulation in the different systems.

Sepsis is the most common cause of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients, and the development of kidney dysfunction prolongs hospitalization and is associated with an unacceptably high mortality rate in septic patients (6, 19, 89, 110). Sepsis induces defects in renal tubule function in association with fluid and electrolyte imbalances that potentiate sepsis pathogenesis (5, 20, 29, 44, 65, 77, 79–81, 94, 101). Significant among these is the development of metabolic acidosis, which contributes to multiple organ dysfunction (7, 32, 47, 50) and is a significant marker of poor outcome and increased mortality in septic patients (32, 33, 51, 63). It is increasingly recognized that maladaptive responses of tubule epithelial cells to inflammatory stimuli play an important role in renal dysfunction during sepsis (110). Our studies provide the first evidence that the endogenously released inflammatory molecule HMGB1 acts directly through RAGE to impair the transport function of renal tubules. The effect of HMGB1 to inhibit HCO3− absorption in the MTAL would contribute to sepsis pathogenesis by impairing the ability of the kidneys to correct systemic acidosis that negatively impacts sepsis outcome through multiple mechanisms, including adverse effects on the cardiovascular, nervous, and immune systems (32, 47, 50, 51, 63). HMGB1 and RAGE levels are increased in kidneys of septic mice (16, 37) and HMGB1 has been shown to upregulate RAGE expression and signaling in several systems (60, 85). These findings raise the possibility that the effect of HMGB1 to inhibit HCO3− absorption may be enhanced in the MTAL during sepsis due to upregulation of basolateral RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 signaling. This possibility is supported by our previous demonstration that sepsis enhances inhibition of MTAL HCO3− absorption by LPS through upregulation of basolateral TLR4 signaling (101). Thus it will be important in future studies to determine whether HMGB1-RAGE signaling is upregulated in the MTAL during sepsis and whether therapeutic targeting of the HMGB1-RAGE pathway suppresses HMGB1 inhibition of HCO3− absorption and attenuates sepsis-associated metabolic acidosis. Of additional interest is whether activation of RAGE by HMGB1 and other RAGE ligands may contribute to MTAL dysfunction in other inflammatory disorders. For example, a direct effect of AGEs to inhibit MTAL HCO3− absorption through RAGE could impair the ability of the kidneys to attenuate metabolic acidosis in poorly controlled diabetes.

An additional finding of our studies is that HMGB1 and LPS inhibit HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through different pathways. HMGB1 and LPS inhibit HCO3− absorption through the activation of different basolateral membrane receptors: HMGB1 through RAGE and LPS through TLR4 (29, 100). The current study extends those observations by identifying the specific signaling molecules and transport mechanisms that distinguish HMGB1- and LPS-induced inhibition. Specifically, basolateral LPS inhibits HCO3− absorption by stimulating a TLR4-MyD88-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 pathway coupled primarily to inhibition of NHE3 (27, 100); HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption by stimulating a RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 pathway coupled primarily to inhibition of NHE1. The two pathways are distinct, which accounts for the fact that the inhibitory effects of HMGB1 and LPS on HCO3− absorption are fully additive (29) 1. These results introduce a new paradigm for renal tubule dysfunction during sepsis, whereby endogenous damage-associated molecules (HMGB1) and exogenous pathogen-associated molecules (LPS) function directly and independently to impair MTAL HCO3− absorption through the activation of different receptor signaling and transport mechanisms. Recent work suggests that HMGB1 is an important convergence point through which multiple immunostimulatory pathways activate innate immune and inflammatory responses (19). An important stimulus for HMGB1 secretion is LPS, which induces the release of HMGB1 with a delayed time course (8–16 h) (4, 70, 93, 108). HMGB1 thus functions as a late mediator of proinflammatory responses in sepsis (4, 52, 60, 70, 93, 108), and targeting HMGB1 attenuates kidney injury and protects mice against lethal endotoxemia and sepsis (4, 37, 52, 108). In the context of the current study, these findings suggest that LPS and HMGB1 would interact functionally and temporally to mediate renal tubule dysfunction during sepsis. That is, the early, rapid effect of LPS to inhibit MTAL HCO3− absorption through TLR4 would be perpetuated and amplified in the later sepsis phase by the additive inhibitory effect of HMGB1 through RAGE. These findings underscore the need for a synergistic treatment strategy that targets multiple innate immune pathways to preserve renal tubule function during sepsis (19, 73, 110).

In summary, the results of the present study show that the endogenous damage-associated molecule HMGB1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in the MTAL through the activation of a RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 signaling pathway. This pathway is coupled primarily to inhibition of the basolateral Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1, which results in inhibition of HCO3− absorption. These studies establish that extracellular HMGB1 can act directly through RAGE to impair the transport function of renal tubules. They identify the RhoA-ROCK1 signaling pathway as a molecular mediator of RAGE-induced transport inhibition in the MTAL and show that NHE1 is a downstream target of HMGB1-RAGE signaling in renal epithelial cells. The effect of HMGB1 to inhibit renal tubule HCO3− absorption may impair the ability of the kidneys to correct metabolic acidosis that is associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients. Inhibition of MTAL HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 through RAGE-ROCK1 is distinct from inhibition by LPS through TLR4-ERK, which enables the two inflammatory molecules to act directly and independently during sepsis to impair MTAL function. These results support the need for a multitargeted therapeutic approach and identify the HMGB1-RAGE-RhoA-ROCK1 pathway as a potential target to preserve renal tubule function in sepsis and other inflammatory disorders.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-038217.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.A.W. and D.W.G. provided conception and design of research; B.A.W., T.G., and A.B. performed experiments; B.A.W. and D.W.G. analyzed data; B.A.W. and D.W.G. interpreted results of experiments; B.A.W. and D.W.G. prepared figures; B.A.W. and D.W.G. edited and revised manuscript; B.A.W. and D.W.G. approved final version of manuscript; D.W.G. drafted manuscript.

Footnotes

HMGB1 stimulates inflammatory responses through activation of TLR4 in some systems (4, 40, 107); however, our results show that TLR4 plays no role in the inhibition of HCO3− absorption by HMGB1 in the MTAL, and provide no evidence of interaction or cross-talk between the basolateral HMGB1-RAGE and LPS-TLR4 pathways that inhibit HCO3− absorption (29).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aktories K, Just I. Clostridial Rho-inhibiting protein toxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 291: 113–145, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander RT, Furuya W, Szaszi K, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Rho GTPases dictate the mobility of the Na/H exchanger NHE3 in epithelia: Role in apical retention and targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 23: 12253–12258, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amano M, Nakayama M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase/ROCK: a key mediator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton 67: 545–554, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson U, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection. Annu Rev Immunol 29: 139–162, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austgen TR, Chen MK, Moore W, Souba WW. Endotoxin and renal glutamine metabolism. Arch Surg 126: 23–27, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Ronco C, Kellum JA. Septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 431–439, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgart K, Radermacher P, Calzia E, Hauser B. Pathophysiology of tissue acidosis in septic shock: Blocked microcirculation or impaired cellular respiration. Crit Care Med 36: 640–642, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianchi ME, Agresti A. HMG proteins: dynamic players in gene regulation and differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Develop 15: 496–506, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi R, Kastrisianaki E, Giambanco I, Donato R. S100B protein stimulates microglia migration via RAGE-dependent up-regulation of chemokine expression and release. J Biol Chem 286: 7214–7226, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biemesderfer D, Reilly RF, Exner M, Igarashi P, Aronson PS. Immunocytochemical characterization of Na+-H+ exchanger isoform NHE-1 in rabbit kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F833–F840, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biemesderfer D, Rutherford PA, Nagy T, Pizzonia JH, Abu-Alfa AK, Aronson PS. Monoclonal antibodies for high-resolution localization of NHE3 in adult and neonatal rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F289–F299, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourguignon LYW, Singleton PA, Diedrich F, Stern R, Gilad E. CD44 interaction with Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE1) creates acidic microenvironments leading to hyaluronidase-2 and cathepsin B activation and breast tumor cell invasion. J Biol Chem 279: 26991–27007, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruchfeld A, Qureshi AR, Lindholm B, Barany P, Yang L, Stenvinkel P, Tracey KJ. High mobility group box protein -1 correlates with renal function in chronic kidney disease. Mol Med 14: 109–115, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bu D, Rai V, Shen X, Rosario R, Lu Y, D'Agati V, Yan SF, Friedman RA, Nuglozeh E, Schmidt AM. Activation of the ROCK1 branch of the transforming growth factor-β pathway contributes to RAGE-dependent acceleration of atherosclerosis in diabetic ApoE-null mice. Circ Res 106: 1040–1051, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bubb MR, Senderowicz AMJ, Sausville EA, Duncan LK, Korn ED. Jasplakinolide, a cytotoxic natural product, induces actin polymerization and competitively inhibits the binding of phalloidin to F-actin. J Biol Chem 269: 14869–14871, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castoldi A, Braga TT, Correa-Costa M, Aguiar CF, Bassi EJ, Correa-Silva R, Elias RM, Salvador F, Moraes-Vieira PM, Cenedeze MA, Reis MA, Hiyane MI, Pacheco-Silva A, Goncalves GM, Camara NOS. TLR2, TLR4 and the MyD88 signaling pathway are crucial for neutrophil migration in acute kidney injury induced by sepsis. PLoS One 7: e37584, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Agati V, Schmidt AM. RAGE and the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 6: 352–360, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Vito P. The sodium/hydrogen exchanger: a possible mediator of immunity. Cell Immunol 240: 69–85, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doi K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PST, Star RA. Animal models of sepsis and sepsis-induced kidney injury. J Clin Invest 119: 2868–2878, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Achkar TM, Hosein M, Dagher PC. Pathways of renal injury in systemic gram-negative sepsis. Eur J Clin Invest 38: 39–44, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng XJ, Liu SX, Wu C, Kang PP, Liu QJ, Hao J, Li HB, Li F, Zhang YJ, Fu XH, Zhang SB, Zuo LF. The PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway mediates HMGB1-induced cell proliferation by regulating the NF-κB/cyclin D1 pathway in mouse mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 306: C1119–C1128, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Good DW. Inhibition of bicarbonate absorption by peptide hormones and cyclic adenosine monophosphate in rat medullary thick ascending limb. J Clin Invest 85: 1006–1013, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Good DW. The thick ascending limb as a site of renal bicarbonate reabsorption. Semin Nephrol 13: 225–235, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Good DW, Di Mari JF, Watts BA III. Hyposmolality stimulates Na+/H+ exchange and HCO3− absorption in thick ascending limb via PI3-kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1443–C1454, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Good DW, George T, Watts BA III. Basolateral membrane Na+/H+ exchange enhances HCO3− absorption in rat medullary thick ascending limb: evidence for functional coupling between basolateral and apical membrane Na+/H+ exchangers. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 92: 12525–12529, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Good DW, George T, Watts BA III. Nerve growth factor inhibits Na+/H+ exchange and HCO3− absorption through parallel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mTOR and ERK pathways in thick ascending limb. J Biol Chem 283: 26602–26611, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Good DW, George T, Watts BA III. Lipopolysaccharide directly alters renal tubule transport through distinct TLR4-dependent pathways in basolateral and apical membranes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F866–F874, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Good DW, George T, Watts BA III. Toll-like receptor 2 is required for LPS-induced Toll-like receptor 4 signaling and inhibition of ion transport in renal thick ascending limb. J Biol Chem 287: 20208–20220, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Good DW, George T, Watts BA III. High mobility group box 1 inhibits HCO3− absorption in medullary thick ascending limb through a basolateral receptor for advanced glycation end products pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F720–F730, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Good DW, Watts BA III. Functional roles of apical membrane Na+/H+ exchange in rat medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F691–F699, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Good DW, Watts BA III, George T, Meyer J, Shull GE. Transepithelial HCO3− absorption is defective in renal thick ascending limbs from NHE1 Na+/H+ exchanger null mutant mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1244–F1249, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunnerson KJ, Kellum JA. Acid-base and electrolyte analysis in critically ill patients: are we ready for the new millennium? Curr Opin Crit Care 9: 468–473, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunnerson KJ, Saul M, He S, Kellum JA. Lactate versus non-lactate metabolic acidosis: a retrospective outcome evaluation of critically ill patients. Crit Care 10: R22–R30, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamm LL, Alpern RJ, Preisig PA. Cellular mechanisms of renal tubular acidification. In: Seldin and Giebisch's The Kidney (5th ed), edited by Alpern RJ, Moe OW, Caplan M. New York: Elsevier, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirose A, Tanikawa T, Mori H, Okada Y, Tanaka Y. Advanced glycation end products increase endothelial permeability through the RAGE/Rho signaling pathway. FEBS Lett 584: 61–66, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffman M, Drury S, Caifeng F, Qu W, Lu Y, Avila C, Kambhan N, Slattery T, McClary J, Nagashima M, Morser J, Stern D, Schmidt AM. RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: the cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell 97: 889–901, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu YM, Pai MH, Yeh CL, Yeh SL. Glutamine administration ameliorates sepsis-induced kidney injury by downregulating the high-mobility group box protein-1-mediated pathway in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F150–F158, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudson BI, Kalea AZ, del Mar Arriero M, Harja E, Boulanger E, D'Agati VD, Schmidt AM. Interaction of the RAGE cytoplasmic domain with Diaphanous-1 is required for ligand-stimulated cellular migration through activation of Rac1 and Cdc42. J Biol Chem 283: 34457–34468, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huttunen HJ, Fages C, Rauvala H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products-mediated neurite outgrowth and activation of NF-кB require the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor but different downstream signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 274: 19919–19924, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibrahim AI, Armour CL, Phipps S, Sukkar MB. RAGE and TLRs: relatives, friends or neighbors? Mol Immunol 56: 739–744, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Julian L, Olson MF. Rho-associated coiled-coil containing kinases: structure, regulation, and functions. Small GTPases 5: e29846, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 11: 373–384, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kierdorf K, Fritz G. RAGE regulation and signaling in inflammation and beyond. J Leukoc Biol 94: 55–68, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klenzak J, Himmelfarb J. Sepsis and the kidney. Crit Care Clin 21: 211–222, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Komers R. Rho kinase inhibition in diabetic nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20: 77–83, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kranenburg O, Poland M, van Horck FPG, Drechsel D, Hall A, Moolenaar WH. Activation of RhoA by lysophosphatidic acid and Gα12/13 subunits in neuronal cells: Induction of neurite retraction. Mol Biol Cell 10: 1851–1857, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraut JA, Madias NE. Treatment of acute metabolic acidosis: a pathophysiologic approach. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 589–601, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kruger B, Krick S, Dhillon N, Lerner SM, Ames S, Bromberg JS, Lin M, Walsh L, Vella J, Fischereder M, Kramer BK, Colvin RB, Heeger PS, Murphy BT, Schroppel B. Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 9: 3390–3395, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuhn S, Geyer M. Formins as effector proteins of Rho GTPases. Small GTPases 5: 1–15, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lardner A. The effects of extracellular pH on immune function. J Leukoc Biol 69: 522–530, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee SW, Hong YS, Park DW, Chio SH, Moon SW, Park JS, Kim JY, Baek KJ. Acidosis not hyperlactatemia as a predictor of in hospital mortality in septic emergency patients. Emerg Med J 25: 659–665, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leelahavanichkul A, Huang Y, Hu X, Tsuji T, Chen R, Kopp JB, Schnermann J, Yuen PST, Star RA. Chronic kidney disease worsens sepsis and sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by releasing High Mobility Group Box Protein-1. Kidney Int 80: 1198–1211, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li L, Zhong K, Sun Z, Wu G, Ding G. Receptor for advanced glycation end products partially mediates HMGB1-ERKs activation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 138: 11–22, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin M, Yiu WH, Wu HJ, Chan LYY, Leung JCK, Au WS, Chan KW, Lai KN, Tang SCW. Toll-like receptor 4 promotes tubular inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 86–102, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meima ME, Mackley JR, Barber DL. Beyond ion translocation: structural functions of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform-1. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 365–372, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meima ME, Webb BA, Witkowska HE, Barber DL. The sodium-hydrogen exchanger NHE1 is an Akt substrate necessary for actin filament reorganization by growth factors. J Biol Chem 284: 2666–2675, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mong PY, Petrulio C, Kaufman HL, Wang Q. Activation of Rho kinase by TNF-α is required for JNK activation in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol 180: 550–558, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mudaliar H, Pollock C, Komala MG, Chadban S, Wu H, Panchapakesan U. The roll of Toll-like receptor proteins 2 and 4 in mediating inflammation in proximal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F143–F154, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muller S, Scaffidi P, Degryse B, Bonaldi T, Ronfani L, Agresti A, Beltrame M, Bianchi ME. The double life of HMGB1 chromatin protein: architectural factor and extracellular signal. EMBO J 20: 4337–4340, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Musumeci D, Roviello GN, Montesarchio D. An overview on HMGB1 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents in HMGB1-related pathologies. Pharmacol Ther 141: 347–357, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neeper M, Schmidt AM, Brett J, Yan SD, Wang F, Pan YE, Elliston K, Stern D, Shaw A. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J Biol Chem 267: 14998–15004, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishiki K, Tsuruoka S, Kawaguchi A, Sugimoto K, Schwartz GJ, Suzuki M, Imai M, Fujimura A. Inhibition of Rho-kinase reduces renal Na-H exchanger activity and causes natriuresis in rat. J Pharm Exp Ther 304: 723–728, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noritomi DT, Soriano FG, Kellum JA, Cappi SB, Biselli PJC, Liborio AB, Park M. Metabolic acidosis in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: A longitudinal quantitative study. Crit Care Med 37: 2733–2739, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nozaki Y, Kinoshita K, Hino S, Yano T, Niki K, Hirooka Y, Kishimoto K, Funauchi M, Matsumura I. Signaling Rho-kinase mediates inflammation and apoptosis in T cells and renal tubules in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F899–F909, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olesen ETB, de Seigneux S, Wang G, Lutken SC, Frokiaer J, Kwon TH, Nielsen S. Rapid and segmental specific dysregulation of AQP2, S256-pAQP2 and renal sodium transporters in rats with LPS-induced endotoxaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2338–2349, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Diversity of the mammalian sodium/proton exchanger SLC9 gene family. Pflügers Arch 447: 549–565, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park EY, Kim BH, Lee EJ, Chang ES, Kim DW, Choi SY, Park JH. Targeting of receptor for advanced glycation end products suppresses cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Biol Chem 289: 9254–9262, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parker MD, Myers EJ, Schelling JR. Na+-H+ exchanger-1 regulation in kidney proximal tubule. Cell Mol Life Sci 72: 2061–2074, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peng F, Wu D, Gao B, Ingram AJ, Zhang B, Chorneyko K, McKenzie R, Krepinsky JC. RhoA/Rho-kinase contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetic renal disease. Diabetes 57: 1683–1692, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pisetsky DS. The translocation of nuclear molecules during inflammation and cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 1117–1125, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Preisig PA, Alpern RJ. Basolateral membrane H/HCO3 transport in renal tubules. Kidney Int 39: 1077–1086, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rabadi MM, Ghali T, Goligorsky MS, Ratliff BB. HMGB1 in renal ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F873–F885, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rabb H, Griffin MD, McKay DB, Swaminathan S, Pikkers P, Rosner MH, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Inflammation in AKI: Current understanding, key questions, and knowledge gaps. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 371–379, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. RAGE: therapeutic target and biomarker of the inflammatory response - the evidence mounts. J Leukoc Biol 86: 505–512, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reninger N, Lau K, McCalla D, Eby B, Cheng B, Lu Y, Qu W, Quadri N, Ananthakrishnan R, Furmansky M, Rosario R, Song F, Rai V, Weinberg A, Friedman R, Ramasamy R, D'Agati VD, Schmidt AM. Deletion of the receptor for advanced glycation end products reduces glomerulosclerosis and preserves renal function in the diabetic OVE26 mouse. Diabetes 59: 2043–2054, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riento K, Ridley AJ. ROCKs: multifunctional kinases in cell behavior. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 446–456, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodrigues CE, Sanches TR, Volpini RA, Shimizu MHM, Kuriki PS, Camara NOS, Seguro AC, Andrade L. Effects of continuous erythropoietin receptor activator in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury and multi-organ dysfunction. PLoS One 7: e29893, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosin DL, Okusa MD. Dangers within: DAMP responses to damage and cell death in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 416–425, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schmidt C, Hocherl K, Bucher M. Regulation of renal glucose transporters during severe inflammation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F804–F811, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmidt C, Hocherl K, Schweda F, Kurtz A, Bucher M. Regulation of renal sodium transporters during severe inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1072–1083, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schrier RW, Wang W. Acute renal failure and sepsis. N Engl J Med 351: 159–169, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shi Y, Dong K, Caldwell M, Sun D. The role of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 in inflammatory responses: maintaining H+ homeostasis of immune cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 961: 411–418, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shum WW, Da Silva N, Belleannee C, McKee M, Brown D, Breton S. Regulation of V-ATPase recycling via a RhoA- and ROCKII-dependent pathway in epididymal clear cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C31–C43, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Snabaitis AK, Cuello F, Avkiran M. Protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylates and inhibits the cardiac Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1. Circ Res 103: 881–890, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Giambanco I, Donato R. RAGE in tissue homeostasis, repair and regeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833: 101–109, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tamma G, Klussmann E, Maric K, Aktories K, Svelto M, Rosenthal W, Valenti G. Rho inhibits cAMP-induced translocation of aquaporin-2 into the apical membrane of renal cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1092–F1101, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tanji N, Markowitz GS, Fu C, Kislinger T, Taguchi A, Pischetsrieder M, Stern D, Schmidt AM, D'Agati D. Expression of advanced glycation end products and their cellular receptor RAGE in diabetic nephropathy and nondiabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1656–1666, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tominaga T, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Barber DL. p160ROCK mediates RhoA activation of Na-H exchange. EMBO J 17: 4712–4722, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]