This is the first integrative metabolic and functional study of the effects of modest hypoxia-inducible factor manipulation within the heart. Of particular note, the combination (and correlation) of perfused heart metabolic flux measurements with the new technique of real-time in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy using hyperpolarized pyruvate is a novel development.

Keywords: hypoxia-inducible factor, magnetic resonance imaging, hyperpolarized pyruvate

Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) appears to function as a global master regulator of cellular and systemic responses to hypoxia. HIF pathway manipulation is of therapeutic interest; however, global systemic upregulation of HIF may have as yet unknown effects on multiple processes. We used a mouse model of Chuvash polycythemia (CP), a rare genetic disorder that modestly increases expression of HIF target genes in normoxia, to understand what these effects might be within the heart. An integrated in and ex vivo approach was employed. Compared with wild-type controls, CP mice had evidence (using in vivo magnetic resonance imaging) of pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular hypertrophy, and increased left ventricular ejection fraction. Glycolytic flux (measured using [3H]glucose) in the isolated contracting perfused CP heart was 1.8-fold higher. Net lactate efflux was 1.5-fold higher. Furthermore, in vivo 13C-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) of hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate revealed a twofold increase in real-time flux through lactate dehydrogenase in the CP hearts and a 1.6-fold increase through pyruvate dehydrogenase. 31P-MRS of perfused CP hearts under increased workload (isoproterenol infusion) demonstrated increased depletion of phosphocreatine relative to ATP. Intriguingly, no changes in cardiac gene expression were detected. In summary, a modest systemic dysregulation of the HIF pathway resulted in clear alterations in cardiac metabolism and energetics. However, in contrast to studies generating high HIF levels within the heart, the CP mice showed neither the predicted changes in gene expression nor any degree of LV impairment. We conclude that the effects of manipulating HIF on the heart are dose dependent.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

This is the first integrative metabolic and functional study of the effects of modest hypoxia-inducible factor manipulation within the heart. Of particular note, the combination (and correlation) of perfused heart metabolic flux measurements with the new technique of real-time in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy using hyperpolarized pyruvate is a novel development.

prolonged hypoxia results in diverse changes within multiple organ systems: ventilatory acclimatization, increased erythropoiesis, pulmonary vascular remodeling, and metabolic alterations occur (54). Many of these diverse cellular and systemic responses to hypoxia are, or are likely to be, coordinated by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) family of transcription factors. HIF is a heterodimer, comprising an oxygen-regulated α-subunit (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or HIF-3α) and a ubiquitous β-subunit (HIF-1β). The stability of HIF-α subunits is regulated by oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylation [by prolyl-4-hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs)], which enables recognition by the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) ubiquitin E3 ligase and subsequent degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (31, 54). Hence, HIF appears to function as a global master regulator of cellular and systemic responses to hypoxia in all metazoan species studied to date (36).

There is considerable interest in understanding further the role of HIF in both individual organ systems and within integrative physiology, driven in part by the potential benefits of VHL-HIF pathway manipulation in the treatment of cancer and vascular disease (49). For example, global systemic upregulation of HIF may have as yet unknown effects on multiple cellular and physiological processes. We sought to understand what these effects might be within the heart.

Exposure of animals and humans to sustained hypoxia results in a consistent pattern of myocardial alterations in metabolic gene expression, substrate utilization, energetics, and function. The dynamic changes in gene expression increase the capacity for glucose uptake (63) and utilization (1, 62), whereas capacity for fatty acid utilization is reduced (62). Indeed, myocardial glucose uptake is increased in high-altitude natives (21) and in rats exposed to hypobaric hypoxia (28). These alterations in substrate utilization may affect myocardial energetics and function: lower phosphocreatine (PCr)-to-ATP ratios were observed in Sherpa hearts (20), in lowlanders exposed to 20 h of normobaric hypoxia (with accompanying diastolic dysfunction) (22), and in trekkers travelling to Everest base camp at 5,300 meters (also with impaired diastolic function) (23).

It is of note that the cardiac metabolic changes seen in response to hypoxia are similar to those observed in heart failure (34, 43–45). Indeed, it has been hypothesized that myocardial hypoxia, with consequent activation of the HIF pathway, may play a role in altering cardiac substrate utilization, energetics, and contractile function; these changes may then cause or exacerbate heart failure. This hypothesis has been explored in experiments producing very high levels of HIF in the heart, from which it is clear that major alterations in HIF give rise to metabolic changes and cardiomyopathy (7, 24, 29, 35, 40, 41). However, these experiments do not reveal whether more modest alterations in HIF, particularly at a systemic level, produce similar results.

Chuvash polycythemia (CP) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder with the potential to address this question. CP arises from a single point mutation in VHL, which diminishes the binding affinity of the protein for hydroxylated HIF-1α and HIF-2α, increasing the expression of HIF target genes under normoxic conditions (2, 14). Patients with CP develop polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, increased ventilatory and pulmonary vascular sensitivity to hypoxia, and altered skeletal muscle metabolism and energetics (14, 65) although any effects on cardiac function remain unidentified. Many aspects of the human disease have been shown to be faithfully recapitulated in the mouse model (18, 19, 39, 64).

The CP mouse therefore provides a unique opportunity to study the effects on the heart of long-term systemic activation of the HIF pathway at more “physiological” levels, without the confounding influence of periods of reduced oxygen availability through hypoxia. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the cardiac metabolic and functional phenotype of CP, using both in and ex vivo techniques.

METHODS

Animals.

CP breeding pairs were donated, and the original mutation was generated on a C57BL6 background as described previously (18). CP and wild-type (homozygous, WT) mice (from the same breeding colony of mice heterozygous for the VHL Chuvash mutation) were used for all comparisons. All animal procedures were compliant with both the United Kingdom Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, institution licence no. 30/2306, and the Local Ethical Review Procedures (University of Oxford Medical Sciences Division Ethical Review Committee). Mice were housed within individually ventilated cages, in room air, with free access to food and water.

Hematology and analysis of plasma metabolites.

Following excision of the heart for perfusion, blood was collected immediately from the chest cavity. Hematocrits, in a heparinized capillary tube, were measured using a hematocrit centrifuge (Hettich); hemoglobin was measured using a HemoCue Hb 201+ (HemoCue). The remaining blood was centrifuged at 4°C, and the plasma was subsequently frozen in liquid nitrogen. All plasma analysis was performed on an ABX Pentra 400 Clinical Chemistry analyzer (Horiba).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Anesthesia was induced using 5%, and maintained with 1–2%, isoflurane in 100% O2. Respiratory rate and ECG were monitored continuously. Cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed as described previously (58). Mice were placed in a purpose-built cradle that was lowered in a vertical-bore 11.7-T (500-MHz) system (Magnex) with a 40-mm birdcage coil (Bruker). A stack of contiguous 1-mm-thick true short-axis ECG- and respiration-gated cine/FLASH images were acquired to cover the entire heart. Image data were analyzed using the ImageJ software (NIH Image). End-systole (ES) and end-diastole (ED) frames for each slice were identified, and the left ventricle (LV) endo- and epicardial borders were outlined in all slices to give values for end-systolic volume (ESV) and end-diastolic volume (EDV). Stroke volume (SV = EDV − ESV), ejection fraction [= (SV/EDV) × 100], and cardiac output (= SV × heart rate) were calculated. LV mass was calculated as the product of the LV volume and the specific gravity of myocardium (1.05 g/cm3). The midventricular slice was defined as the one in which the papillary muscles were most prominent; right ventricle (RV) free wall thickness was measured in three separate locations in this slice, and subsequently averaged.

To quantify septal bowing (the distortion of the LV), a novel method was used. First, the LV epicardial border in early diastole in the midventricular slice was outlined, giving an actual perimeter length (PA) and area (AA). The maximum possible area enclosed by a perimeter of any given length arises when the figure is a circle. For a perimeter of length PA, we denote this area as AC. If the LV were perfectly circular, then the ratio of AA to AC would be 1. As the LV becomes increasingly distorted in shape AA falls relative to AC, and hence the ratio will fall below 1. This “septal bowing ratio” thus enables quantification of the distortion of the septum using the LV itself as the comparator. We chose to quantify septal bowing in this way, since it is an approach that is likely to be relatively insensitive to observer variability. We expect that a relatively linear relationship would exist between this index and other indexes of septal bowing, such as the ratio between the long and short axes in a short-axis ventricular slice [as introduced by Ryan et al. (56) and which correlates with pulmonary artery pressure in patients with pulmonary hypertension], but this has not been tested directly.

Gene expression (real-time PCR).

Total RNA was extracted from 20–30 mg powdered (in liquid nitrogen) whole heart tissue (following Langendorff perfusion) and whole lung tissue. Total RNA was extracted using the Rneasy Fibrous Kit (Qiagen), including a DNase treatment step, and cDNA immediately synthesized from 1 μg RNA using the Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). Real-Time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (choosing manufacturer-recommended assays; Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification of mRNA expression levels was determined using the standard curve method and normalized to β-actin (heart tissue) or 18s ribosomal RNA (lung tissue).

Gene expression (microarray).

Total RNA was extracted from 20–30 mg powdered (in liquid nitrogen) whole heart tissue using the Rneasy Fibrous Kit (Qiagen), including a DNase treatment step. The RNA integrity was assessed on a BioAnalyzer (Agilent Laboratories); all samples had a RNA Integrity Number ≥7. Labeled sense single-strand DNA (ssDNA) for hybridization was generated from 200 ng starting RNA with the Ambion WT expression kit (P/N 4411973) and the Affymetrix GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling and Controls Kit (P/N 901525) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The distribution of fragmented sense ssDNA lengths was measured on the BioAnalyzer. The fragmented ssDNA was labeled and hybridized for 17 h at 45°C to the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mouse 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix). Chips were processed on an Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 and Scanner 3000. Affymetrix Command Console was used to generate cel files, and Affymetrix Expression Console was used for the quality control. Arrays were RMA normalized in GeneSpring GX 12, and differentially expressed genes were identified using Limma with a Benjamini and Hochberg multiple testing correction of ≤0.05. Because few genes were detected using this method, the data were reanalyzed using PLIER normalization and a Student's t-test with a P value cutoff of ≤0.05 and a fold change difference between WT and Chuvash of ≥1.3.

Isolated heart perfusion.

Mice were terminally anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbitol sodium (500 mg/kg; Merial), and the heart was excised and arrested in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer; blood was immediately collected from the chest cavity for subsequent analysis. The ascending aorta was cannulated, and the heart was perfused retrograde in Langendorff mode at 37°C at a constant perfusion pressure of 80 mmHg. A polyethylene balloon, connected to a pressure transducer and used to measure cardiac function, was inserted in the LV lumen, and its volume was adjusted to produce an end-diastolic pressure of 4–8 mmHg. Rate pressure product (RPP) was calculated as the product of LV developed pressure (systolic pressure − end-diastolic pressure) and heart rate. Hearts were perfused with 100 ml of a modified Krebs-Henseleit recirculating buffer (in mmol/l: 118 NaCl, 3.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.97 CaCl2, 0.5 Na2EDTA, 25 NaHCO3, and 1.2 KH2PO4) containing 11 mmol/l glucose and 0.4 mmol/l palmitate prebound to 1.5% albumin as substrates. The buffer was continually gassed with a mix of 95% O2 with 5% CO2.

Perfused heart energetics.

Perfused hearts were inserted in an 11.7-T (500-MHz) vertical bore (123 mm internal diameter) magnet (Magnex Scientific) with a 10-mm probe (Rapid) containing concentric 1H- and 31P-sensitive coils. Fully relaxed 31P spectra were acquired using pulse-and-collect sequence at a repetition time of 10 s and a flip angle of 90° (32 averages, total acquisition time of 5 min, steady state). Approximate doubling of the RPP was then achieved by an infusion of isoproterenol (concentration received by the heart 2–5 nM), and further spectra were acquired (minimum acquisition time 5 min). Spectra were analyzed using the jMRUI software (42) to give values for PCr and γ-ATP abundance, and the ratio of these two. Spectra for each perfusion condition (standard, or isoproterenol) were averaged to give final values for PCr/ATP.

Measurement of cardiac substrate metabolism.

To determine glycolytic flux in the perfused heart, 50 μCi of d-[5-3H]glucose (Amersham) were added to the recirculating buffer. Following a 10-min stabilization period, perfusate samples were collected at 5-min intervals for 35 min. 3H2O was separated from the d-[5-3H]glucose in the time samples using Dowex ion exchange resin (Sigma) and subsequently used to calculate the glycolytic rate. Because of the position of the 3H label, this method gives a measure of true glycolytic rate since the label is cleaved by enolase in the cytosol.

Cardiac lactate efflux was determined by measuring lactate concentration spectrophotometrically in timed perfusate collections using lactate dehydrogenase. This method gives a measure of net lactate efflux from the heart. Cardiac palmitate oxidation rates were determined in a separate group of perfused hearts by adding 50 μCi of [9,10-3H]palmitate (Amersham) to the recirculating buffer and performing a chloroform-methanol Folch extraction on the time buffer samples to collect the 3H2O.

Measurement of in vivo cardiac metabolism in real time.

Mice were studied in the early absorptive (fed) state, between 1:00 and 11:00 A.M. They were anesthetized in isoflurane and O2, and intravenous access was gained using a 32-G tail-vein cannula. Mice were then positioned within a 7-T horizontal-bore MR scanner. Respiratory rate and ECG were monitored continuously. As described previously (12), 0.15 ml of hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate (0.48 mmol/kg) was injected over 10 s followed by a 0.05-ml flush of heparinized saline to clear the delivery line. Sixty individual ECG-gated 13C-MR cardiac spectra were acquired over 1 min following injection and subsequently analyzed using the AMARES algorithm in the jMRUI software package [version 4.0 (42)]. The peak areas of [13C1]pyruvate, [13C1]lactate, [13C1]alanine, and [13C1]bicarbonate at each time point were quantified and used as input data for a kinetic model, as described previously (12).

Statistical analysis.

Differences between groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance using SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM).

RESULTS

The purpose of this study was to determine the cardiac metabolic and functional phenotype of the CP mouse compared with the WT.

General hematological and biochemical characteristics of the CP mouse model.

Body mass, basic hematology, and plasma metabolites are summarized in Table 1. Polycythemia in the CP mice was confirmed by demonstrating a modest increase in both hemoglobin and hematocrit, consistent with previous reports (18, 19, 64). No differences were seen in nonfasting plasma metabolites.

Table 1.

Basic hematological and other parameters

| Wild Type | n | Chuvash | n | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass, g | |||||

| Male mice | 35.9 ± 0.7 | 12 | 28.4 ± 0.4 | 12 | < 0.001* |

| Female mice | 25.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 8 | 0.016* |

| Hematocrit, % | 43 ± 0.6 | 13 | 51 ± 1.0 | 13 | < 0.001* |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 138 ± 3 | 16 | 158 ± 4 | 13 | < 0.001* |

| Glucose, mmol/l | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 7 | 13.4 ± 0.5 | 7 | 0.96 |

| Hydroxybutyrate, mmol/l | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 8 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 7 | 0.65 |

| Nonesterified fatty acid, mmol/l | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 8 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 7 | 0.33 |

| Triacylglycerol, mmol/l | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 7 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 7 | 0.56 |

| Cholesterol, mmol/l | 1.7 ± 0.20 | 8 | 1.6 ± 0.05 | 7 | 0.44 |

Results are means ± SE; n, no. of mice. Hematological values, nonfasting plasma metabolites, and body masses of mice aged 6-7 mo are shown.

P < 0.05.

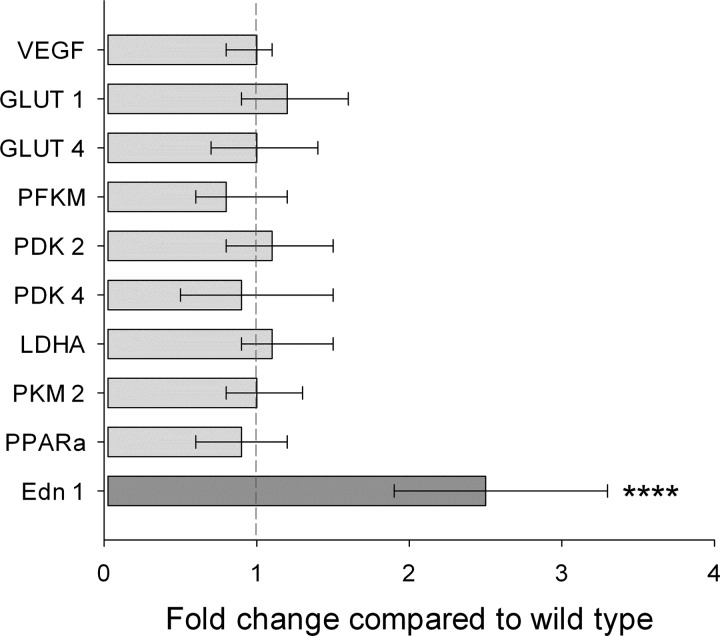

CP mice have normal cardiac metabolic gene expression.

The whole heart expression of key cardiac metabolic genes revealed no differences between WT and CP mice (Fig. 1). To confirm the methodology, the expression of lung endothelin-1 was studied and found to be significantly increased in the CP mice, in keeping with previous findings (19). The full microarray results are included in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 (Supplemental material for this article is available online at the Journal website.).

Fig. 1.

Cardiac and lung gene expression. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to measure expression of key metabolic genes in hearts from wild-type (WT, n = 9) and Chuvash polycythemia (CP, n = 7) mice, aged 6–7 mo. To confirm the methodology, expression of endothelin-1 (Edn 1; dark gray) was also determined in lungs from 13 WT and 11 CP mice. Values are means ± 95% confidence interval. VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; GLUT, glucose transporter; PFKM, phosphofructokinase; PDK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; PKM, pyruvate kinase muscle; PPARa, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α. ****P < 0.001.

CP mice exhibit features of pulmonary hypertension.

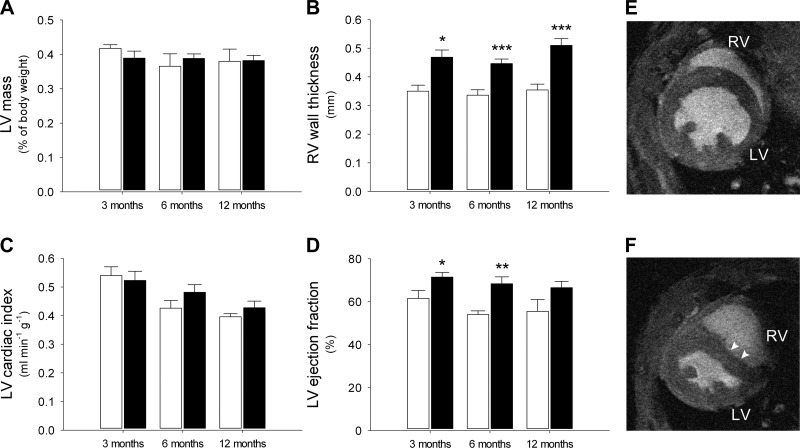

Cardiac function and mass in WT and CP mice at different ages are shown in Fig. 2. A full table of cine MRI results is included in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

In vivo cardiac function. In vivo cine magnetic resonance imaging was used to measure cardiac mass and function in aging WT and CP mice (n = 3–8 mice/group). Open bars, WT; closed bars, CP. A: left ventricle (LV) mass; B: right ventricle (RV) wall thickness; C: LV cardiac output, corrected to body mass; D: LV ejection fraction. WT mice had normal cardiac morphology (E, representative image of mouse aged 3–6 mo). CP mice demonstrated marked interventricular septal bowing, particularly in early diastole (F; arrowheads, representative image of mouse aged 3–6 mo). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.02, and ***P < 0.01.

Table 2.

Full cine MRI data

| Wild Type | n | Chuvash | n | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass, g | |||||

| 3 mo | 28 ± 1.8 | 4 | 24 ± 1.3 | 7 | 0.093 |

| 6 mo | 36 ± 1.1 | 4 | 25 ± 1.2 | 9 | < 0.0001* |

| 12 mo | 37 ± 3.2 | 5 | 27 ± 0.9 | 8 | 0.003* |

| LV ejection fraction, % | |||||

| 3 mo | 61.5 ± 3.7 | 3 | 71.5 ± 2.2 | 6 | 0.043* |

| 6 mo | 54.0 ± 1.7 | 4 | 68.4 ± 3.2 | 8 | 0.014* |

| 12 mo | 55.5 ± 5.6 | 5 | 66.5 ± 2.9 | 8 | 0.078 |

| LV mass, %body mass | |||||

| 3 mo | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 3 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 6 | 0.262 |

| 6 mo | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 5 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 7 | 0.584 |

| 12 mo | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 5 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 8 | 0.952 |

| MV RV wall thickness, mm | |||||

| 3 mo | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 3 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 7 | 0.021* |

| 6 mo | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 5 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 8 | 0.001* |

| 12 mo | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 5 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 7 | 0.001* |

| Septal bowing ratio | |||||

| 3 mo | 0.91 ± 0.009 | 3 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 7 | 0.038* |

| 6 mo | 0.92 ± 0.004 | 5 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 7 | < 0.0001* |

| 12 mo | 0.93 ± 0.0 | 4 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 7 | < 0.0001* |

| Heart rate, beats/min | |||||

| 3 mo | 420 ± 29 | 3 | 373 ± 8 | 6 | 0.069 |

| 6 mo | 413 ± 10 | 5 | 398 ± 3 | 8 | 0.202 |

| 12 mo | 418 ± 3 | 5 | 402 ± 7 | 8 | 0.129 |

| Stroke volume, ml | |||||

| 3 mo | 35.1 ± 2.9 | 3 | 32.2 ± 1.2 | 7 | 0.282 |

| 6 mo | 34.5 ± 1.0 | 5 | 30.8 ± 2.3 | 8 | 0.24 |

| 12 mo | 37.1 ± 1.5 | 4 | 28.1 ± 1.4 | 8 | 0.003* |

| Cardiac output, ml/min | |||||

| 3 mo | 14.8 ± 2.0 | 3 | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 7 | 0.226 |

| 6 mo | 14.3 ± 0.5 | 5 | 12.2 ± 0.9 | 8 | 0.116 |

| 12 mo | 14.6 ± 1.2 | 5 | 11.3 ± 0.7 | 8 | 0.025* |

| LV cardiac index, ml·min−1·g−1 | |||||

| 3 mo | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 3 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 7 | 0.756 |

| 6 mo | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 5 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 8 | 0.197 |

| 12 mo | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 5 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 8 | 0.322 |

Results are means ± SE; n, no. of mice. For the "septal bowing ratio," the greater the distortion of the left ventricle (LV) by the septum, the greater the deviation from the perfect circle ratio of 1.0. MV, midventricular; RV, right ventricle.

P < 0.05.

RV free wall hypertrophy, a typical feature of pulmonary hypertension, was seen in all age groups in the CP mice (Fig. 2B). These findings were comparable with those reported in a previous study in which pulmonary artery pressure and RV free wall thickness were measured using invasive techniques (19). In addition, marked interventricular septal bowing, another characteristic feature of pulmonary hypertension, was seen in all age groups in the CP mice (Fig. 2F). The degree of septal bowing was quantified and is included in Table 2.

In contrast to the marked changes in the RV, no differences were seen in LV mass or cardiac output (corrected for body mass; Fig. 2, A and C). Interestingly, LV ejection fraction was significantly increased in the younger CP mice, perhaps as a result of the pulmonary hypertension (Fig. 2D).

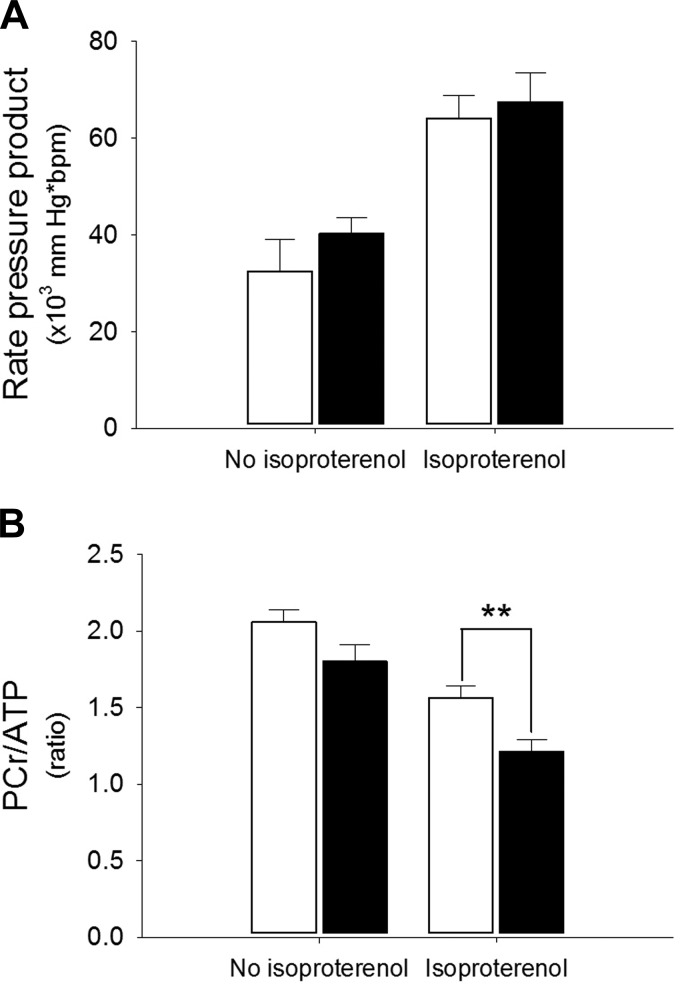

CP hearts exhibit more marked depletion of PCr under conditions of high workload.

31P-MR spectroscopy of Langendorff-perfused hearts enabled the measurement of cardiac energetics under conditions of both normal and high workload. Although cardiac energetics were similar in WT and CP hearts perfused under normal conditions, an infusion of isoproterenol (causing an approximate doubling in RPP) resulted in significantly lower PCr/ATP ratios in the CP hearts compared with WT controls (PCr/ATP 1.21 ± 0.08 in CP vs. 1.56 ± 0.08, P < 0.02) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Perfused-heart energetics. 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy was performed on perfused hearts from WT and CP mice (n = 5 in each group), aged 6–7 mo. Body mass 30.1 ± 2.1 g for WT vs. 28.7 ± 1.2 for CP (not significant). Open bars, WT; closed bars, CP. Hearts were perfused under normal Langendorff conditions using palmitate buffer, and spectra were acquired, both without and with an infusion of isoproterenol to increase the rate pressure product (RPP). As expected, isoproterenol significantly increased the RPP (P < 0.001) and decreased the PCR-to-ATP ratio (P < 0.001). No significant difference between WT and CP was detected without isoproterenol, but following the increase in RPP the PCr/ATP ratio was significantly lower in the CP hearts compared with WT controls. A: RPP; B: PCr/ATP ratio. **P < 0.02.

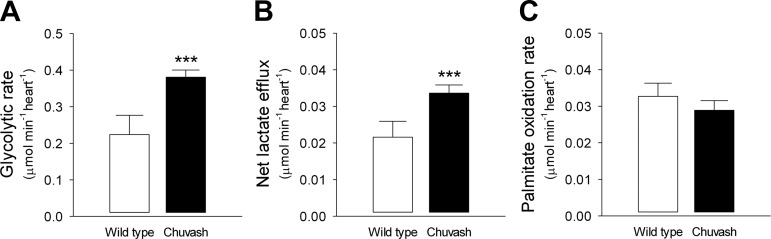

Glycolytic flux and lactate efflux are increased in the CP heart.

Glycolytic flux in the perfused heart, measured using [3H]glucose, was 1.8-fold higher in the CP heart compared with WT controls (Fig. 4A). Analysis of variance, using genotype (CP or WT) as the fixed factor and heart mass and RPP as covariates, demonstrated that the CP mutation was the only significant determining factor on glycolytic rate (P = 0.004 for genotype; P = 0.095 for heart weight; P = 0.147 for RPP). Similarly, net lactate efflux was 1.5-fold higher in the CP hearts (P = 0.009 for genotype; P = 0.121 for heart weight; P = 0.123 for RPP) (Fig. 4B). There was a significant correlation between glycolytic and lactate efflux rates (Pearson r = 0.935, P < 0.0001). In contrast to the increased glucose utilization and lactate production by the CP hearts, a decrease in fatty acid oxidation [as might be predicted by the Randle cycle (27)] was undetectable (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Perfused heart metabolism. Glycolytic flux (A) and net lactate efflux (B) were determined in WT (n = 4) and CP (n = 7) mice, aged 15–17 mo. Body mass 33.8 ± 1.8 g for WT vs. 29.4 ± 1.6 for CP (not significant). Glycolytic and lactate rates were highly correlated (Pearson r = 0.935, P < 0.001). Palmitate oxidation rates (C) were determined in separate mice (n = 5 in each group), aged 11–17 mo. Body mass 27.4 ± 1.5 g for WT vs. 26.2 ± 2.0 for CP (P = 0.034). ***P < 0.01.

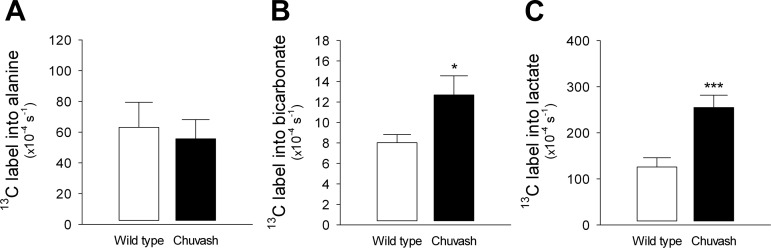

In vivo pyruvate metabolism, measured in real time, is significantly altered in the CP heart.

The advent of dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) has enabled the study of cardiac metabolism in real time (59). In vivo 13C-MR spectroscopy of hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate revealed, in keeping with the perfusion studies, a twofold increase in the rate of 13C1 label incorporation in lactate in the CP hearts (P < 0.01, Fig. 5). Furthermore, there was a 1.6-fold increase in the rate of label incorporation in bicarbonate (P < 0.05), indicating elevated flux through pyruvate dehydrogenase (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

In vivo real-time cardiac metabolism. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy of hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate was performed in WT (n = 5) and CP (n = 4) mice, aged 9–15 mo. Body mass 32.0 ± 3.0 g for WT vs. 27.0 ± 3.0 for CP (not significant). This technique allowed real-time measurement of the rate of label incorporation from pyruvate into alanine (A), bicarbonate (B), or lactate (C). *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

It is now known that HIF functions as a global master regulator, coordinating diverse cellular and systemic responses to hypoxia. Studies on patients and mice have demonstrated that perturbations in the HIF pathway, such as CP or HIF-2α gain-of-function mutations, result in profound abnormalities in systemic and cellular processes that are usually under tight control. Marked changes in skeletal muscle metabolism, ventilation, pulmonary vascular tone, and glucose homeostasis are all observed in both humans and animals with disorders of the HIF pathway (2, 13–16, 18, 19, 37, 39, 46, 48, 50–53, 57, 64–66, 68, 69). We now demonstrate that chronic modest upregulation of HIF due to the Chuvash VHL mutation results in altered cardiac metabolism and energetics in the mouse heart.

A primordial function of HIF-1 is to find the optimal balance between oxidative and glycolytic metabolism for a given local oxygen concentration. As such, HIF-1 target genes, including glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes (30, 60), lactate dehydrogenase (61) and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-1 (33, 47), enable increased glucose metabolism. In both hypoxia and hypoxia-mimetic models, myocardial expression of the master regulator of fatty acid metabolism, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα), is decreased together with its downstream targets such as pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 (1, 55, 62). Alterations in cardiac mitochondrial oxidative metabolism are also seen (17). Thus, one would predict that exposure to hypoxia, or chronic activation of the HIF pathway, would result in an increased reliance upon glycolysis and glucose oxidation and a shift away from fatty acid β-oxidation.

Most studies investigating the role of HIF in cardiac metabolism and function have employed tactics either to overexpress HIF itself or to impair its degradation by using altered levels of PHDs or VHL. Mice with cardiomyocyte-specific loss of VHL have elevated HIF levels in the heart, accompanied by increased expression of glycolytic genes, cellular lipid accumulation, and progressive heart failure (35). Combined cardiac-specific loss of both PHD2 and PHD3 results in increased expression of phosphoglycerate kinase, decreased expression of PPARα, myocyte accumulation of lipid, and severe cardiomyopathy (41). Conditional somatic inactivation of PHDs produces similar results (40). Inducible cardiac-specific overexpression of an oxygen-stable form of HIF-1α results in increased transcript levels of glycolytic genes and progressively impaired cardiac function (7). Furthermore, long-term constitutive overexpression of HIF-1α results in increased glucose uptake and the development of cardiomyopathy (24). Taken together, these studies have shown that very high levels of HIF in the heart result in a switch in gene expression toward increased glucose metabolism, with accompanying contractile dysfunction. In contrast, shorter-term constitutive overexpression of HIF-1α mRNA in cardiomyocytes did not result in cardiomyopathy, but this construct only produced a barely detectable increase in HIF in normoxia. Interestingly, this overexpression was protective during myocardial infarction, where hypoxia would be expected to be present (32).

Our study investigated the cardiac effects of the Chuvash VHL mutation in mice, which results in systemic long-term modest upregulation of HIF. Our model faithfully recapitulated findings seen in previous studies on CP patients and mice [raised hemoglobin and hematocrit, pulmonary hypertension (shown using noninvasive MRI), and RV hypertrophy (using MRI, rather than histology)]. However, a surprising feature of our study was the apparent lack of change in the expression of key metabolic genes within the heart, despite clear alterations in substrate metabolism and energetics. It is possible that our whole heart analysis masked differential changes that could have been seen in the left, vs. the right, ventricle (1, 62). Alternatively, the presence of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy may have resulted in genetic remodeling in addition to that caused by the Chuvash VHL mutation. Finally, it is possible that the LV in the CP mouse is exposed to a chronic increase in local and/or systemic sympathetic drive (9, 10, 38, 67), which may also alter gene transcription on the background of that caused by the HIF upregulation itself.

Previous studies of HIF manipulation within the mouse heart have demonstrated an increased reliance upon glucose metabolism, with accompanying contractile dysfunction (7, 24, 35, 40, 41). In the much more modest perturbation of the HIF system in the current study, these two features were not coupled, in keeping with a previous study demonstrating that short-term HIF mRNA overexpression could be cardioprotective (32). While there was clear evidence of increased glucose utilization and altered energetics, LV function was enhanced rather than diminished. It is likely that this increased ejection fraction is a reflection of the pulmonary hypertension demonstrated in the CP mice. One potential mechanism is that bowing of the interventricular septum arises as a consequence of the elevated pulmonary arterial pressure, and this could result directly in a reduced LV end-systolic volume. Another possible mechanism is that there is an overall increased sympathetic drive to the heart to maintain the cardiac output in the face of an elevated pulmonary vascular resistance. Again, this would be expected to result in a reduced LV end-systolic volume. It should also be noted that cell types other than cardiomyocytes may be relevant. For example, endothelial cell-specific HIF has been shown to influence cardiac glucose uptake, and this would have effects both in vivo and on the isolated perfused-heart preparation (26).

The balance between myocardial glucose and fatty acid metabolism can be studied using the combination of radiolabeled substrates and the isolated perfused heart (6, 8). We have demonstrated that the hearts from CP mice have elevated glycolytic flux, accompanied by increased net lactate efflux. This finding is in keeping with previous genetic studies that have shown that long-term constitutive overexpression of HIF-1α in the heart results in increased glucose uptake (24) and that cardiac-specific loss of HIF-1α causes decreased cardiomyocyte lactate concentrations (25). In our study, the increase in glycolytic flux was greater than that of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) flux, meaning that the decrease in palmitate oxidation did not reach significance. However, following hypoxia, mouse hearts have been shown to have increased glycolytic flux, increased lactate production, and significantly decreased fatty acid oxidation (11).

The advent of DNP enables flux through metabolic pathways to be measured in real time in vivo. This technique has recently been optimized for use in small animals, such as mice, allowing genetic models to be studied for the first time (5, 12). The increased sensitivity [>10,000-fold (3)] of DNP allows the acquisition of data within 1 min after infusion of a bolus of hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate. This bolus is required to be relatively large; however, during the short time frame of data acquisition, no perturbation of plasma metabolites (other than pyruvate) or PDH activity occurs (4, 5). Using hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate MR spectroscopy, we have shown that there is increased rate of label incorporation from pyruvate in both lactate (via lactate dehydrogenase) and bicarbonate (via PDH). By using a combination of techniques, we have therefore demonstrated that the measurements of metabolic flux obtained ex vivo are in agreement with those made in real time in vivo.

Metabolic flexibility is required for the heart to continue to perform under conditions of varying workload. Inflexibility, due to increased reliance on a substrate such as glucose (which yields less ATP per molecule compared with fatty acids), may result in myocardial energy depletion. In agreement with this hypothesis, we have demonstrated that myocardial energetics, quantified by measurement of PCr and ATP, are reduced in the CP perfused heart under conditions of increased workload. Altered cardiac energetics are a feature of both heart failure (45) and hypoxia (20, 22, 23); our study adds to this body of evidence by demonstrating that modest long-term upregulation of HIF may result in a similar finding.

In summary, a modest systemic dysregulation of the HIF pathway, caused by the Chuvash VHL mutation, resulted in clear alterations in cardiac metabolism and energetics. However, in contrast to studies generating high levels of HIF in the heart, the CP mice showed neither the predicted changes in gene expression nor any degree of LV impairment. We conclude that the effects of manipulating HIF on the heart are dose dependent. In the present study, the pulmonary hypertension associated with CP clearly had a significant effect on cardiac function. In future studies employing the CP mutation to study modest HIF dysregulation, targeting this mutation specifically to cardiac myocytes could obviate the influence of pulmonary hypertension.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (WT090123AIA, to M. Slingo), Diabetes UK (11/0004175 to L. C. Heather), and by the British Heart Foundation (FS/10/002/28078 to D. Tyler). Equipment support was provided to D. Tyler by GE Healthcare, UK.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.S., M.A.C., L.C.H., D.J.T., K.C., and P.A.R. conception and design of research; M.S., M.A.C., C.A.C., M.K.C., M.S.D., L.G., and L.C.H. performed experiments; M.S., M.A.C., C.A.C., M.K.C., M.S.D., L.C.H., D.J.T., and K.C. analyzed data; M.S., M.A.C., C.A.C., M.K.C., M.S.D., L.C.H., D.J.T., K.C., and P.A.R. interpreted results of experiments; M.S. prepared figures; M.S. drafted manuscript; M.S., L.C.H., K.C., and P.A.R. edited and revised manuscript; M.S., M.A.C., C.A.C., M.K.C., M.S.D., L.G., L.C.H., D.J.T., K.C., and P.A.R. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emma Carter and Vicky Ball for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrogue JV, Sharma S, Ngumbela K, Essop MF, Taegtmeyer H. Acclimatization to chronic hypobaric hypoxia is associated with a differential transcriptional profile between the right and left ventricle. Mol Cell Biochem 278: 71–78, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, Gordeuk VR, Jelinek J, Guan Y, Liu E, Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, Mole D, Maxwell PH, Stockton DW, Semenza GL, Prchal JT. Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet 32: 614–621, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of >10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10158–10163, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton HJ, Schroeder MA, Dodd MS, Heather LC, Carter EE, Cochlin LE, Nagel S, Sibson NR, Radda GK, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. Validation of the in vivo assessment of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity using hyperpolarised 13C MRS. NMR Biomed 24: 201–208, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakermans AJ, Dodd MS, Nicolay K, Prompers JJ, Tyler DJ, Houten SM. Myocardial energy shortage and unmet anaplerotic needs in the fasted long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase knockout mouse. Cardiovasc Res 100: 441–449, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr RL, Lopaschuk GD. Direct measurement of energy metabolism in the isolated working rat heart. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 38: 11–17, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekeredjian R, Walton CB, MacCannell KA, Ecker J, Kruse F, Outten JT, Sutcliffe D, Gerard RD, Bruick RK, Shohet RV. Conditional HIF-1alpha expression produces a reversible cardiomyopathy. PloS one 5: e11693, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belke DD, Larsen TS, Lopaschuk GD, Severson DL. Glucose and fatty acid metabolism in the isolated working mouse heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R1210–R1217, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciarka A, Doan V, Velez-Roa S, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Prognostic significance of sympathetic nervous system activation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 1269–1275, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciarka A, Vachiery JL, Houssiere A, Gujic M, Stoupel E, Velez-Roa S, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Atrial septostomy decreases sympathetic overactivity in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 131: 1831–1837, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole MA, Abd Jamil AH, Heather LC, Murray AJ, Sutton ER, Slingo M, Sebag-Montefiore L, Tan SC, Aksentijevic D, Gildea OS, Stuckey DJ, Yeoh KK, Carr CA, Evans RD, Aasum E, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ, Neubauer S, Robbins PA, Clarke K. On the pivotal role of PPARalpha in adaptation of the heart to hypoxia and why fat in the diet increases hypoxic injury. FASEB J In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodd MS, Ball V, Bray R, Ashrafian H, Watkins H, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. In vivo mouse cardiac hyperpolarized magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Cardiovasc Magnet Res 15: 19, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Formenti F, Beer PA, Croft QP, Dorrington KL, Gale DP, Lappin TR, Lucas GS, Maher ER, Maxwell PH, McMullin MF, O'Connor DF, Percy MJ, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Smith TG, Talbot NP, Robbins PA. Cardiopulmonary function in two human disorders of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway: von Hippel-Lindau disease and HIF-2alpha gain-of-function mutation. FASEB J 25: 2001–2011, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Formenti F, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Emmanuel Y, Cheeseman J, Dorrington KL, Edwards LM, Humphreys SM, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, McNamara CJ, Mills W, Murphy JA, O'Connor DF, Percy MJ, Ratcliffe PJ, Smith TG, Treacy M, Frayn KN, Greenhaff PL, Karpe F, Clarke K, Robbins PA. Regulation of human metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 12722–12727, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, Niu X, Nouraie M, Okhotin DJ, Polyakova LA, Ammosova T, Nekhai S, Ganz T, Prchal JT. Chuvash polycythemia VHLR200W mutation is associated with down-regulation of hepcidin expression. Blood 118: 5278–5282, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordeuk VR, Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, Okhotin D, Voloshin Y, Choyke PL, Butman JA, Jedlickova K, Prchal JT, Polyakova LA. Congenital disorder of oxygen sensing: association of the homozygous Chuvash polycythemia VHL mutation with thrombosis and vascular abnormalities but not tumors. Blood 103: 3924–3932, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heather LC, Cole MA, Tan JJ, Ambrose LJ, Pope S, Abd-Jamil AH, Carter EE, Dodd MS, Yeoh KK, Schofield CJ, Clarke K. Metabolic adaptation to chronic hypoxia in cardiac mitochondria. Basic Res Cardiol 107: 268, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickey MM, Lam JC, Bezman NA, Rathmell WK, Simon MC. von Hippel-Lindau mutation in mice recapitulates Chuvash polycythemia via hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha signaling and splenic erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest 117: 3879–3889, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickey MM, Richardson T, Wang T, Mosqueira M, Arguiri E, Yu H, Yu QC, Solomides CC, Morrisey EE, Khurana TS, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Simon MC. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation promotes pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 827–839, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochachka PW, Clark CM, Holden JE, Stanley C, Ugurbil K, Menon RS. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the Sherpa heart: a phosphocreatine/adenosine triphosphate signature of metabolic defense against hypobaric hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 1215–1220, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holden JE, Stone CK, Clark CM, Brown WD, Nickles RJ, Stanley C, Hochachka PW. Enhanced cardiac metabolism of plasma glucose in high-altitude natives: adaptation against chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 79: 222–228, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holloway C, Cochlin L, Codreanu I, Bloch E, Fatemian M, Szmigielski C, Atherton H, Heather L, Francis J, Neubauer S, Robbins P, Montgomery H, Clarke K. Normobaric hypoxia impairs human cardiac energetics. FASEB J 25: 3130–3135, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloway CJ, Montgomery HE, Murray AJ, Cochlin LE, Codreanu I, Hopwood N, Johnson AW, Rider OJ, Levett DZ, Tyler DJ, Francis JM, Neubauer S, Grocott MP, Clarke K, Caudwell G, Xtreme Everest Research. Cardiac response to hypobaric hypoxia: persistent changes in cardiac mass, function, and energy metabolism after a trek to Mt Everest Base Camp. FASEB J 25: 792–796, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holscher M, Schafer K, Krull S, Farhat K, Hesse A, Silter M, Lin Y, Pichler BJ, Thistlethwaite P, El-Armouche A, Maier LS, Katschinski DM, Zieseniss A. Unfavourable consequences of chronic cardiac HIF-1alpha stabilization. Cardiovasc Res 94: 77–86, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Hickey RP, Yeh JL, Liu D, Dadak A, Young LH, Johnson RS, Giordano FJ. Cardiac myocyte-specific HIF-1alpha deletion alters vascularization, energy availability, calcium flux, and contractility in the normoxic heart. FASEB J 18: 1138–1140, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Lei L, Liu D, Jovin I, Russell R, Johnson RS, Di Lorenzo A, Giordano FJ. Normal glucose uptake in the brain and heart requires an endothelial cell-specific HIF-1alpha-dependent function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 17478–17483, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hue L, Taegtmeyer H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E578–E591, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurford WE, Crosby G, Strauss HW, Jones R, Lowenstein E. Ventricular performance and glucose uptake in rats during chronic hypobaric hypoxia. J Nnuclear Med 31: 1344–1351, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyvarinen J, Hassinen IE, Sormunen R, Maki JM, Kivirikko KI, Koivunen P, Myllyharju J. Hearts of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylase-2 hypomorphic mice show protection against acute ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem 285: 13646–13657, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, Gassmann M, Gearhart JD, Lawler AM, Yu AY, Semenza GL. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev 12: 149–162, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaelin WG Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30: 393–402, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kido M, Du L, Sullivan CC, Li X, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha reduces infarction and attenuates progression of cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction in the mouse. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 2116–2124, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab 3: 177–185, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamb HJ, Beyerbacht HP, van der Laarse A, Stoel BC, Doornbos J, van der Wall EE, de Roos A. Diastolic Dysfunction in Hypertensive Heart Disease Is Associated With Altered Myocardial Metabolism. Circulation 99: 2261–2267, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lei L, Mason S, Liu D, Huang Y, Marks C, Hickey R, Jovin IS, Pypaert M, Johnson RS, Giordano FJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent degeneration, failure, and malignant transformation of the heart in the absence of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Mol Cell Biol 28: 3790–3803, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loenarz C, Coleman ML, Boleininger A, Schierwater B, Holland PW, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ. The hypoxia-inducible transcription factor pathway regulates oxygen sensing in the simplest animal, Trichoplax adhaerens. EMBO Rep 12: 63–70, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenzo FR, Yang C, Ng Tang Fui M, Vankayalapati H, Zhuang Z, Huynh T, Grossmann M, Pacak K, Prchal JT. A novel EPAS1/HIF2A germline mutation in a congenital polycythemia with paraganglioma. J Mol Med 91: 507–512, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mak S, Witte KK, Al-Hesayen A, Granton JJ, Parker JD. Cardiac sympathetic activation in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R1153–R1157, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClain DA, Abuelgasim KA, Nouraie M, Salomon-Andonie J, Niu X, Miasnikova G, Polyakova LA, Sergueeva A, Okhotin DJ, Cherqaoui R, Okhotin D, Cox JE, Swierczek S, Song J, Simon MC, Huang J, Simcox JA, Yoon D, Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Decreased serum glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels in patients with Chuvash polycythemia: a role for HIF in glucose metabolism. J Mol Med 91: 59–67, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Bardeesy N, Cullen D, Bronson RT, Kaelin WG Jr. Somatic inactivation of the PHD2 prolyl hydroxylase causes polycythemia and congestive heart failure. Blood 111: 3236–3244, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moslehi J, Minamishima YA, Shi J, Neuberg D, Charytan DM, Padera RF, Signoretti S, Liao R, Kaelin WG Jr. Loss of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in cardiomyocytes phenocopies ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 122: 1004–1016, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naressi A, Couturier C, Castang I, de Beer R, Graveron-Demilly D. Java-based graphical user interface for MRUI, a software package for quantitation of in vivo/medical magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals. Comp Biol Med 31: 269–286, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neubauer S. The failing heart–an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med 356: 1140–1151, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neubauer S, Horn M, Cramer M, Harre K, Newell JB, Peters W, Pabst T, Ertl G, Hahn D, Ingwall JS, Kochsiek K. Myocardial phosphocreatine-to-ATP ratio is a predictor of mortality in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 96: 2190–2196, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neubauer S, Horn M, Pabst T, Godde M, Lubke D, Jilling B, Hahn D, Ertl G. Contributions of 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy to the understanding of dilated heart muscle disease. Eur Heart J 16, Suppl O: 115–118, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niu X, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, Polyakova LA, Okhotin DJ, Tuktanov NV, Nouraie M, Ammosova T, Nekhai S, Gordeuk VR. Altered cytokine profiles in patients with Chuvash polycythemia. Am J Hematolgy 84: 74–78, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab 3: 187–197, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pastore YD, Jelinek J, Ang S, Guan Y, Liu E, Jedlickova K, Krishnamurti L, Prchal JT. Mutations in the VHL gene in sporadic apparently congenital polycythemia. Blood 101: 1591–1595, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paul SA, Simons JW, Mabjeesh NJ. HIF at the crossroads between ischemia and carcinogenesis. J Cell Physiol 200: 20–30, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Percy MJ. Familial erythrocytosis arising from a gain-of-function mutation in the HIF2A gene of the oxygen sensing pathway. Ulster Med J 77: 86–88, 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Percy MJ, McMullin MF, Jowitt SN, Potter M, Treacy M, Watson WH, Lappin TR. Chuvash-type congenital polycythemia in 4 families of Asian and Western European ancestry. Blood 102: 1097–1099, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrotta S, Nobili B, Ferraro M, Migliaccio C, Borriello A, Cucciolla V, Martinelli V, Rossi F, Punzo F, Cirillo P, Parisi G, Zappia V, Rotoli B, Della Ragione F. Von Hippel-Lindau-dependent polycythemia is endemic on the island of Ischia: identification of a novel cluster. Blood 107: 514–519, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perrotta S, Stiehl DP, Punzo F, Scianguetta S, Borriello A, Bencivenga D, Casale M, Nobili B, Fasoli S, Balduzzi A, Cro L, Nytko KJ, Wenger RH, Della Ragione F. Congenital erythrocytosis associated with gain-of-function HIF2A gene mutations and erythropoietin levels in the normal range. Haematologica 98: 1624–1632, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Adaptive and maladaptive cardiorespiratory responses to continuous and intermittent hypoxia mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. Physiol Rev 92: 967–1003, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Razeghi P, Young ME, Abbasi S, Taegtmeyer H. Hypoxia in vivo decreases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-regulated gene expression in rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 287: 5–10, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryan T, Petrovic O, Dillon JC, Feigenbaum H, Conley MJ, Armstrong WF. An echocardiographic index for separation of right ventricular volume and pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol 5: 918–927, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sable CA, Aliyu ZY, Dham N, Nouraie M, Sachdev V, Sidenko S, Miasnikova GY, Polyakova LA, Sergueeva AI, Okhotin DJ, Bushuev V, Remaley AT, Niu X, Castro OL, Gladwin MT, Kato GJ, Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Pulmonary artery pressure and iron deficiency in patients with upregulation of hypoxia sensing due to homozygous VHL(R200W) mutation (Chuvash polycythemia). Haematologica 97: 193–200, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider JE, Cassidy PJ, Lygate C, Tyler DJ, Wiesmann F, Grieve SM, Hulbert K, Clarke K, Neubauer S. Fast, high-resolution in vivo cine magnetic resonance imaging in normal and failing mouse hearts on a vertical 11.7 T system. J Mag Res Imaging 18: 691–701, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Ball DR, Cole MA, Heather LC, Griffin JL, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. Real-time assessment of Krebs cycle metabolism using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. FASEB J 23: 2529–2538, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seagroves TN, Ryan HE, Lu H, Wouters BG, Knapp M, Thibault P, Laderoute K, Johnson RS. Transcription factor HIF-1 is a necessary mediator of the pasteur effect in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 21: 3436–3444, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, Passantino R, Concordet JP, Maire P, Giallongo A. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 271: 32529–32537, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma S, Taegtmeyer H, Adrogue J, Razeghi P, Sen S, Ngumbela K, Essop MF. Dynamic changes of gene expression in hypoxia-induced right ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1185–H1192, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sivitz WI, Lund DD, Yorek B, Grover-McKay M, Schmid PG. Pretranslational regulation of two cardiac glucose transporters in rats exposed to hypobaric hypoxia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 263: E562–E569, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Slingo ME, Turner PJ, Christian HC, Buckler KJ, Robbins PA. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation in mice causes carotid-body hyperplasia and enhanced ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 116: 885–892, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith TG, Brooks JT, Balanos GM, Lappin TR, Layton DM, Leedham DL, Liu C, Maxwell PH, McMullin MF, McNamara CJ, Percy MJ, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Talbot NP, Treacy M, Robbins PA. Mutation of von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor and human cardiopulmonary physiology. PLoS medicine 3: e290, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tan Q, Kerestes H, Percy MJ, Pietrofesa R, Chen L, Khurana TS, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Lappin TR, Lee FS. Erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model of human HIF2A gain of function mutation. J Biol Chem 288: 17134–17144, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Velez-Roa S, Ciarka A, Najem B, Vachiery JL, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Increased sympathetic nerve activity in pulmonary artery hypertension. Circulation 110: 1308–1312, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang C, Sun MG, Matro J, Huynh TT, Rahimpour S, Prchal JT, Lechan R, Lonser R, Pacak K, Zhuang Z. Novel HIF2A mutations disrupt oxygen sensing, leading to polycythemia, paragangliomas, and somatostatinomas. Blood 121: 2563–2566, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon D, Okhotin DV, Kim B, Okhotina Y, Okhotin DJ, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, Polyakova LA, Maslow A, Lee Y, Semenza GL, Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Increased size of solid organs in patients with Chuvash polycythemia and in mice with altered expression of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha. J Mol Med 88: 523–530, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.