This study shows that anti-TNFα therapy decreased tissue inflammation and both proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine gene expression when given early but not late in the course of peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-PS)-induced enterocolitis. Hence this study provides a translational model that supports the clinical idea that anti-TNF therapy is most effective when begun early in the course of Crohn's disease.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, fibrosis, stricture, animal model

Abstract

Anti-TNFα therapy decreases inflammation in Crohn's disease (CD). However, its ability to decrease fibrosis and alter the natural history of CD is not established. Anti-TNF-α prevents inflammation and fibrosis in the peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-PS) model of CD. Here we studied anti-TNF-α in a treatment paradigm. PG-PS or human serum albumin (HSA; control) was injected into bowel wall of anesthetized Lewis rats at laparotomy. Mouse anti-mouse TNF-α or vehicle treatment was begun day (d)1, d7, or d14 postlaparotomy. Rats were euthanized d21-23. Gross abdominal and histologic findings were scored. Cecal levels of relevant mRNAs were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. There was a stepwise loss of responsiveness when anti-TNFα was begun on d7 and d14 compared with d1 that was seen in the percent decrease in the median gross abdominal score and histologic inflammation score in PG-PS-injected rats [as %decrease; gross abdominal score: d1 = 75% (P = 0.003), d7 = 57% (P = 0.18), d14 = no change (P = 0.99); histologic inflammation: d1 = 57% (P = 0.006), d7 = 50% (P = 0.019), d14 = no change (P = 0.99)]. This was also reflected in changes in IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IGF-I, TGF-β1, procollagen I, and procollagen III mRNAs that were decreased or trended downward in PG-PS-injected animals given anti-TNF-α beginning d1 or d7 compared with vehicle-treated rats; there was no effect if anti-TNF-α was begun d14. This change in responsiveness to anti-TNFα therapy was coincident with a major shift in the cytokine milieu observed on d14 in the PG-PS injected rats (vehicle treated). Our data are consistent with the clinical observation that improved outcomes occur when anti-TNF-α therapy is initiated early in the course of CD.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

This study shows that anti-TNFα therapy decreased tissue inflammation and both proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine gene expression when given early but not late in the course of peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-PS)-induced enterocolitis. Hence this study provides a translational model that supports the clinical idea that anti-TNF therapy is most effective when begun early in the course of Crohn's disease.

crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of unknown etiology and multifactorial pathogenesis that is characterized by a discontinuous pattern of transmural bowel wall inflammation (37). While the natural history of CD can be quite variable (7), by the end of a 25-yr follow-up study most patients had disease that was complicated by fibrostenotic strictures and/or fistulas (29). It has been estimated that CD progresses to a fibrostenotic disease phenotype in one-third of patients (25), resulting in luminal narrowing that frequently requires surgical intervention.

One cytokine believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of CD is tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (5, 39, 41, 48, 52). Biologic therapies aimed at neutralizing TNF-α have been shown to be effective in inducing clinical, endoscopic, and histologic remission of CD, including in some patients whose disease is refractory to standard medical therapies (41, 43). However, the rates of response and rates and duration of remission with anti-TNF-α therapy appear to decrease when the drug is begun late rather than early in the course of CD (23, 41). Because fibrosis occurs in the setting of chronic inflammation (56), anti-TNF-α-induced healing of inflammation in CD may be expected to prevent fibrosis. However, some early reports suggested that anti-TNF-α therapy may, in fact, worsen or trigger fibrosis and cause the clinical sequela, obstruction (8, 50, 54). A subsequent prospective study found that, if confounding factors such as severity of CD, duration of CD, and new corticosteroid use were considered, anti-TNF-α therapy did not increase the risk of bowel obstruction (26). Inflammatory stenoses can be successfully treated with anti-TNF-α, and there are some reports of the successful treatment with anti-TNF-α of the inflammatory component of stenotic lesions that also had a fibrotic component (28, 44). Nevertheless, a recent pilot prospective trial of anti-TNF-α therapy in CD patients with subocclusive strictures was discontinued early because some patients had worsening of their stricture-related symptoms and required surgery (28). Thus uncertainty remains about the safety of administering anti-TNF-α agents to patients with known fibrotic stenoses, and some continue to consider the use of these drugs to be contraindicated in such patients until more is known about how to distinguish between those CD patients with strictures who will benefit from anti-TNF-α therapy vs. those who will not respond or whose symptoms will worsen (18).

The peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-PS) model of CD, carried out in the genetically susceptible Lewis rat strain, is characterized by a chronic granulomatous inflammatory response accompanied by robust fibrosis (15, 32, 38, 59). This model is particularly well-suited to studying the effects of potential CD therapies in that both the disease and model are T-cell mediated and have similar disease distribution, histologic features, tissue cytokine profiles, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components in areas of fibrosis (32, 38, 59). Both the disease and model show genetic susceptibilities. CD may involve host immune response to commensal bacteria due to loss of tolerance (5, 37, 39), and PG-PS is a bacterial cell wall component, the peptidoglycan portion of which contains the muramyl dipeptide moiety that is the ligand for NOD2, which in turn is the product of the major disease-susceptibility gene for CD (16).

We recently showed that anti-TNF-α therapy instituted early in the course of the PG-PS model decreases both inflammatory and fibrotic changes (1). In the studies reported here, we sought to determine whether anti-TNF-α therapy begun later in the course of the model would have similar efficacy. We found that delaying initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy was accompanied by progressive refractoriness to both anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of the drug. Thus our data support use of anti-TNF-α therapy early in the course of the disease; use late in the disease process may not be effective, contributing to worsening disease outcomes. In rats with PG-PS enterocolitis that did not receive anti-TNF-α therapy, there are marked changes in the cytokine and profibrotic factor milieu during the course of the disease with a dramatic increase in profibrotic factors as the model progresses. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that the cytokine milieu present in the tissue at the time the anti-TNF-α therapy is begun determines the response to therapy. This hypothesis requires further study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All animal studies were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals and were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011 (ISBN 978-0-309-15401-7)]. Female Lewis strain rats raised in a specific pathogen free (SPF) environment were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). The rats were housed under standard SPF and temperature-controlled conditions, with light-dark cycles of 12:12 h, and were given unrestricted access to water and standard laboratory chow. Animals were ∼8–10 wk of age (∼150–175 g) at the start of the experiments.

PG-PS enterocolitis model.

As previously described (15, 32, 38, 59), rats anesthetized with ketamine (40–90 mg/kg) in combination with xylazine (5–10 mg/kg) underwent laparotomy. With the use of an aseptic technique, peptidoglycan-polysaccharide from Group A Streptococci (PG-PS; 15 μg rhamnose/g body wt; PG-PS 10S from Lee Laboratories - Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA) was administered by nine intramural injections at five sites along the surgically exposed intestine [the 2 distal Peyer's patches, the distal ileal mesentery (2 injections), cecal tip, and cecal wall (4 injections)] using 33-gauge needles. Control rats were injected with human serum albumin (HSA; 45 μg/g body wt; sterile solution in normal saline) in the same manner. After the operation, the animals were closely monitored, weighed three times per week, and allowed free access to standard rodent chow and water. In this model, PG-PS induces transient acute inflammation that peaks at 1–2 days, followed by a nominally quiescent phase at 7–10 days and then a spontaneously reactivating chronic granulomatous inflammatory phase that begins by days (d)12–17 and is associated with prominent fibrosis (10, 38).

Study design.

Three separate anti-TNF-α treatment experiments were performed, one experiment for each anti-TNF-α treatment initiation time point (1, 7, or 14 days post-PG-PS or -HSA injection; see Table 1); rats were euthanized on d21-23. In a separate experiment, untreated rats (1 HSA- and 3 PG-PS-injected per time point) were euthanized at d1 and d14 postinjection. Three nonoperated rats served as controls for calculation of fold increases of mRNA levels.

Table 1.

Experimental groups in the three anti-TNF-α experiments

| Number of Rats Per Treatment Group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSA injected |

PG-PS injected |

||||||

| Experiment No. | Start of anti-TNFα (days post-PG-PS injection) | Dose, Route, Frequency of anti-TNFα | Euthanasia (days post-PG-PS injection) | Vehicle | Anti-TNFα | Vehicle | Anti-TNFα |

| 1 | d1 | 4.8 mg sc, ×3/wk | d21 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 2 | d7 | 4.8 mg sc, every 2nd day | d23 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 9 |

| 3 | d14 | 4.8 mg sc, every 2nd day | d23 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

PG-PS, peptidoglycan-polysaccharide; HSA, human serum albumin; d, day.

Anti-TNF-α treatment.

8C11, a monoclonal mouse anti-mouse TNF-α produced by standard hybridoma techniques, was provided by Abbvie Bioresearch Center (Worcester, MA). The antibody was provided at 3.89 mg/ml in 15 mM histidine (pH 5.31) in single-use aliquots that were stored at −80°C. The dose of 8C11 to be used was determined in consultation with Abbvie scientists, with consideration given to our previous experience with anti-TNF-α therapy in the PG-PS model of CD. At Abbvie, a dose of 12 mg/kg administered twice per week had been found to be optimal for prevention of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. However, based on our experience using another anti-TNF-α antibody in the PG-PS rat model of Crohn's disease (1), the dose was doubled and the frequency of administration was increased; 4.8 mg of the drug was administered by subcutaneous injection three times per week (experiment 1) or every second day (experiments 2 and 3). The antibody was thawed just before use in a 37°C water bath with constant agitation. Control animals were given an equal volume of vehicle (15 mM histidine, pH 5.31). Treatment was begun on d1 (prevention paradigm), d7 (prevention/treatment paradigm), or d14 (treatment paradigm) in separate experiments and was continued until the animals were euthanized on d21-d23 post-PG-PS or post-HSA injection.

Assay of serum levels of anti-TNF-α.

Blood was collected immediately following euthanasia at the end of each experiment. The blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for 30–60 min and then centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min. Serum was recovered and stored at −80°C. Serum drug levels were measured by Abbvie personnel using a murine TNF-α capture assay and a goat anti-mouse IgG sulfotag, followed by electrochemiluminescence detection (reagents and equipment from Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD).

Gross abdominal score.

At the time of euthanasia, the abdominal contents were grossly evaluated by an observer (E. M. Zimmermann) blinded to the treatments. Cecal wall thickening (based on degree of opacity of the bowel wall and the perceived thickness on palpation), thickening and contraction of the cecal and terminal ileal mesentery, adhesions, cecal nodules, and liver nodules were each graded on a scale of 0 to 4. The composite gross abdominal score (maximum possible = 20) was calculated as the sum of the individual component scores (1, 15, 32, 59).

Histologic evaluation.

At the time of dissection, a 1 × 2 cm portion of the wall of the cecum was resected. One half of this piece of tissue was placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin; the remaining half was frozen for RNA analysis (see below). A 0.5-cm length of the cecal tip was collected and placed in formalin. After 24 h the tissue was removed from formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. From each tissue sample, one section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and another with a modification of Masson's original trichrome stain. This trichrome system stains collagen blue, nuclei purple-brown, and cytoplasm pink. Each tissue section was scored for inflammation and fibrosis (see Table 2; Ref. 32) by a gastrointestinal pathologist (A. C. Rittershaus) blinded to the treatments. The R2 for both intra- and interobserver (vs. B. J. McKenna) variation was 0.9 based on data from the three anti-TNF-α experiments presented here (intra-) or data from a previous study (inter-) (1).

Table 2.

Scheme for histologic scoring of inflammation and fibrosis

| Inflammation |

Fibrosis |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Mucosal (crypt abscesses) | Submucosal | Serosal | Granulomas (number of) | Submucosal | Serosal | Muscularis mucosae | Muscularis externa |

| 0 | None | None | None | 0 | None | None | None | None |

| 1 | Focal | Focal | Focal | 1–2 | Focal | Focal | Focal | Focal |

| 2 | Multifocal | Patchy | Patchy | 3–4 | Patchy | Patchy | Patchy | Patchy |

| 3 | Confluent patchy | Diffuse | Diffuse | 5–9 | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse |

| 4 | Diffuse | Diffuse severe | Diffuse severe | Many/necrotizing | Diffuse severe | Diffuse severe | Diffuse severe | Diffuse severe |

The inflammation score for a given tissue section is the sum of the scores given to the 4 regions or features assessed for inflammation (4 columns under “Inflammation”). The fibrosis score for a given tissue section is the sum of the scores given to the 4 regions assessed for fibrosis (4 columns under “Fibrosis”). Maximum scores are 16 for inflammation and 16 for fibrosis.

Hematocrit.

In the three anti-TNF-α experiments, a portion of the blood collected immediately following euthanasia was anticoagulated with potassium EDTA (experiment 1) or sodium heparin (experiments 2 and 3). Spun hematocrits (50 μl) were performed by the Animal Diagnostic Laboratory of the University of Michigan Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine.

Messenger RNA analyses.

One-half of the 1 × 2 cm portion of PG-PS- or HSA-injected cecum, harvested at the time of dissection as described above, was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and placed at −80°C for later RNA extraction. RNA was isolated from pulverized frozen cecal tissue using the RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and included DNase treatment to prevent later amplification of genomic DNA. The RNA concentration was calculated from the absorbance at 260 nm. A portion of the RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNAs were used in quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions. Primers and probes for procollagen types I and III were previously designed by our laboratory to span an intron (12). All other PCR was done using commercially available TaqMan Gene Expression Assays from Applied Biosystems (IL-1β, Rn00580432_m1; IL-6, Rn01410330_m1; TNF-α, Rn99999017_m1; IGF-I, Rn00710306_m1; TGF-β1, Rn01475963_m1). Thermal cycling (95°C for 10 min followed by up to 40 cycles, each consisting of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C) was done using a Stratagene Mx3000P instrument. With the use of the 2−ΔΔCt method (27), results were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Rn99999916_s1), and fold change was calculated as fold the mean vehicle-treated HSA-injected control value. All reactions were done in triplicate wells. In an attempt to maximize the likelihood of achieving statistical significance in the comparisons of anti-TNF-α-treated vs. vehicle-treated animals, all of the animals in the experiment in which anti-TNF-α treatment was begun on d14 post-PG-PS injection were injected with PG-PS; one-half were treated with anti-TNF-α and one-half were given vehicle. Therefore, three HSA control samples from the d1 experiment were included on the PCR plates of the d14 experiment and were used for fold-control calculations.

Statistical analyses.

The Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn's post hoc test was used for comparisons involving more than two groups of ordinal variables such as gross and histologic scores. If the analysis of ordinal variables was a single comparison between only two groups, such as aggregated gross or histologic scores from all three experiments comparing only PG-PS-injected (vehicle-treated) to HSA-injected (vehicle-treated) rats, then Mann-Whitney analysis was used. These nonparametric results are expressed as a difference in medians by box and whisker plots where the boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR) divided by a horizontal median line, and whiskers show the full range of data extending from the lowest to highest recorded measurement. One-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's post hoc test was used for comparisons involving more than two groups of continuous measurement variables such as hematocrit and cytokine mRNA levels. Two-tailed unpaired t-tests were used for all other single comparisons between two groups of continuous variables including drug level comparisons, aggregated mRNA levels and for d14 vs. d1 comparisons in untreated rats. Results for the continuous measurement variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were done under the guidance of a statistician using Graph Pad Prism V6.0f statistical software. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

We used the peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-PS) Lewis rat model of CD to examine the effects of anti-TNF-α therapy initiated at various stages of the disease process. In aggregate, the PG-PS-injected rats (vehicle-treated; n = 26) from all three of the experiments developed more fibrosis and inflammation than the HSA-injected rats (vehicle-treated; n = 8) by all measures: gross abdominal score (P < 0.0001); histologic inflammation and fibrosis scores (P < 0.0001 for both); and relative levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IGF-I, TGF-β1, and procollagen types I and III mRNAs (all P ≤ 0.0002).

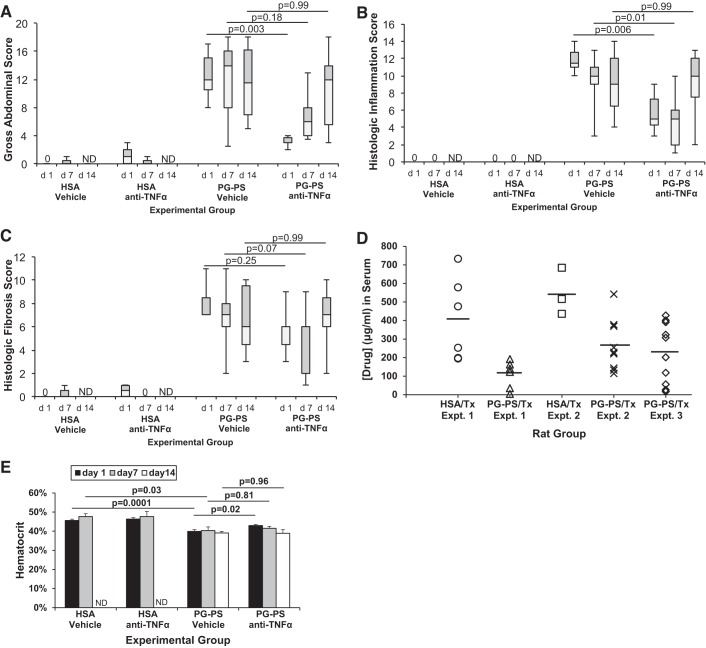

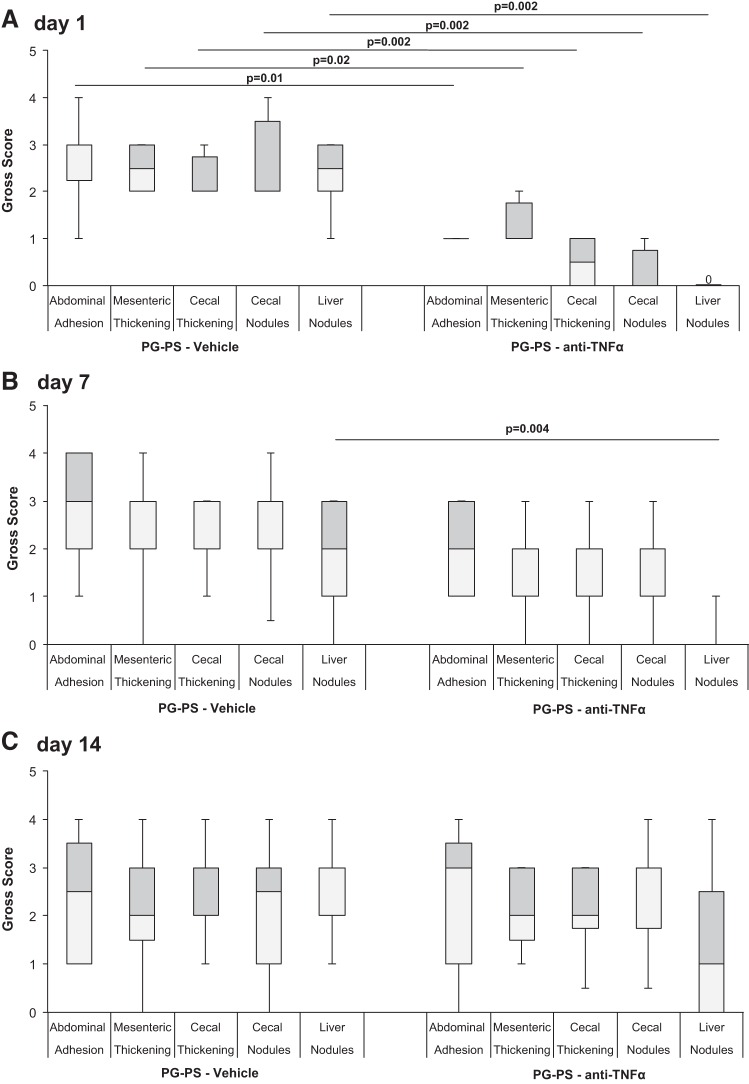

There was a stepwise decrease in the improvement in gross abdominal score in anti-TNF-α-treated PG-PS-injected rats compared with vehicle-treated PG-PS-injected rats when treatment was begun on d7 or d14 compared with d1 (Fig. 1A; d1: 0.25-fold vehicle-treated, n = 6/group, P = 0.003; d7: 0.43-fold, n = 9/group, P = 0.18; d14: 1.04-fold, n = 11/group, P = 0.99). The effects of anti-TNF-α treatment on individual components of the gross abdominal score are shown in Fig. 2. When treatment was begun on d1 post-PG-PS-injection, the scores for all components of the gross abdominal score (adhesions, thickening of cecal and ileal mesentery, cecal wall thickening, cecal nodules, and liver nodules) were significantly decreased in rats treated with anti-TNF-α compared with those given vehicle (Fig. 2A; P = 0.01 to P = 0.002). When the start of anti-TNF-α treatment was delayed until d7 or d14 post-PG-PS injection, the only component of the gross abdominal score that showed improvement was the score for liver nodules at d7 (P = 0.004; Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 1.

Effect of anti-TNF-α therapy begun at various stages of development of PG-PS-induced enterocolitis. The day of intramural injection of peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-PS) or human serum albumin (HSA; control) into the cecum and terminal ileum at laparotomy is considered day (d)0. PG-PS-injected animals have greater gross abdominal, histologic inflammation, and histologic fibrosis scores than HSA-injected animals. Anti-TNF-α therapy reduced gross abdominal and histologic inflammation scores when begun on d1 or d7 after PG-PS injection, but therapy withheld until d14 did not significantly reduce any of the 3 assessments of disease. A: effect on gross abdominal score. Maximum possible score in this subjective assessment of intra-abdominal disease burden is 20. Boxes contain the interquartile range (IQR) showing the upper (grey) and lower (white) quartiles, divided by the median (solid horizontal line), and whiskers extend to the maximum and minimum range. N is as shown in Table 1. Comparisons performed with Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's post hoc. B: effect of anti-TNF-α therapy on histologic inflammation score. Maximum possible score is 16. Boxes are IQR divided by median; whiskers show range; n is as shown in Table 1. Comparisons were performed with Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's post hoc. C: effect of anti- TNF-α therapy on histologic fibrosis score. Maximum possible score is 16. Boxes are IQR divided by median; whiskers show range; n is as shown in Table 1. Comparisons performed with Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's post hoc. D: serum drug levels in anti-TNF-α-treated (Tx) animals at the end of each experiment (d21-23; see Table 1). Time from last dose to serum sampling: experiments 1, 72 h; experiments 2, 48 h; experiments 3, 24 h. Horizontal lines indicate means. In experiments 1 and 2, mean serum drug levels were greater in the HSA-injected than in the PG-PS-injected rats (Student t-test, P = 0.012 for both). When the results for the 3 experiments were considered in aggregate, the mean serum drug level was 452 ± 201 μg/ml in HSA-injected and 216 ± 145 μg/ml in PG-PS-injected rats (Student t-test, P = 0.0006). E: effect of anti-TNF-α therapy on hematocrit when therapy is begun at various stages of development of PG-PS-induced enterocolitis. Compared with HSA-injected rats, rats injected with PG-PS (vehicle-treated) develop anemia. Anti-TNF-α therapy begun d1 post-PG-PS injection attenuates the development of anemia. However, when initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy is delayed until d7 or d14 post-PG-PS injection hematocrits are reduced to the same level as in vehicle-treated PG-PS-injected animals. Results shown are means; error bars reflect SD; n are as shown in Table 1. Comparisons performed with one-way ANOVA and Sidak's post hoc.

Fig. 2.

Individual components of gross abdominal scores in the three anti-TNF-α experiments. Boxes contain the interquartile range (IQR) showing the upper (grey) and lower (white) quartiles, divided by the median (solid horizontal line), and whiskers extend to the maximum and minimum range. N is as shown in Table 1. Pair-wise comparisons between anti-TNF-α and vehicle performed using Mann-Whitney test. A: when treatment was begun on d1 post-PG-PS-injection, the individual scores for all components of the gross abdominal score were significantly decreased in rats treated with anti-TNF-α compared with those given vehicle. B: when the start of anti-TNF-α treatment was delayed until d7 post-PG-PS injection, the only component of the gross abdominal score that showed significant improvement was the score for liver nodules. C: when the start of anti-TNF-α treatment was delayed until d14 post-PG-PS injection, no components of gross abdominal score showed improvement.

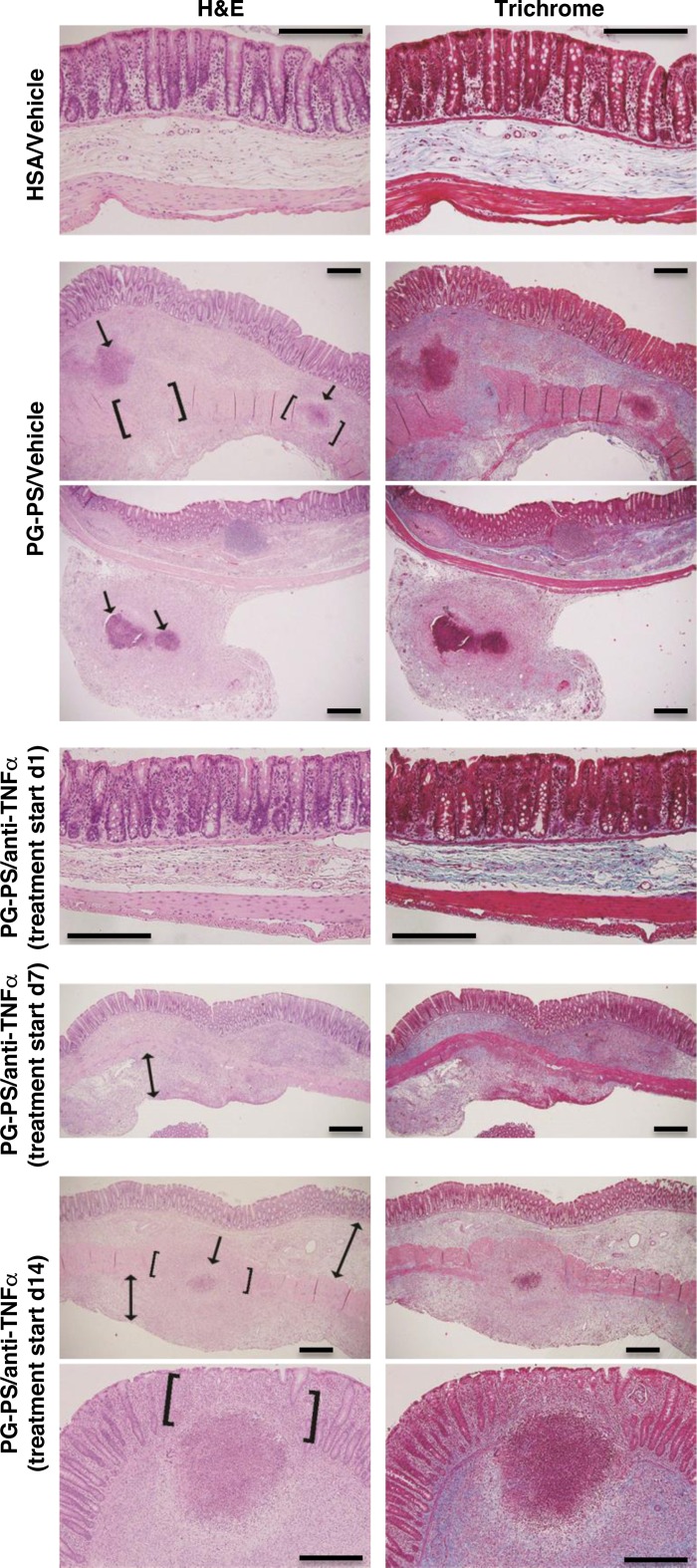

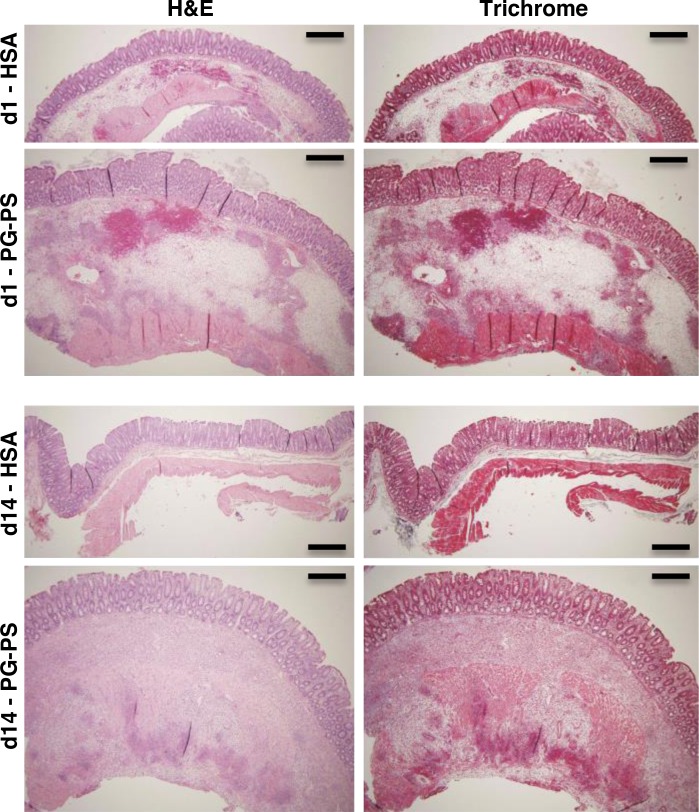

The histologic inflammation score was decreased in anti-TNF-α-treated PG-PS-injected rats compared with vehicle-treated PG-PS-injected rats when treatment was started on d1 or d7 but not d14 (Fig. 1B; d1: 0.43-fold vehicle-treated, P = 0.006; d7: 0.50-fold, P = 0.01; d14: 1.11-fold, P = 0.99). The histologic fibrosis score in PG-PS-injected rats showed a similar trend of diminished score with anti-TNF-α treatment compared with vehicle when treatment was begun on d1 or d7 but not d14 (Fig. 1C; d1: 0.86-fold vehicle-treated, P = 0.25; d7: 0.29-fold, P = 0.07; d14: 1.17-fold, P = 0.99). Representative H&E- and trichrome-stained sections are shown in Fig. 3. As in untreated or vehicle-treated PG-PS-injected rats, fibrotic expansion of the submucosa and subserosa, disruption of the muscularis propria, and granulomas were seen when anti-TNF-α therapy was delayed until d14 post-PG-PS injection.

Fig. 3.

Representative sections of cecal tissue at d21-23 post-PG-PS or HSA injection stained with H&E (left) and trichrome (right). Original magnification: images for HSA/vehicle and PG-PS/anti-TNF-α (treatment started d1), ×20; images at bottom are for PG-PS/anti-TNF-α (treatment started d14), ×10; all others, ×4. Scale bars = 50 μm. Tissue from PG-PS-injected/vehicle-treated rats exhibited granulomatous inflammatory infiltrates (arrows) in the submucosa (images at top) and subserosa (images at bottom). Disruption of the muscularis propria by collagen deposition (brackets) or granuloma (brackets and arrow) was observed. The mesocolon (or pericolic adipose tissue) exhibited increased density due to increased cellularity (pink on trichrome) and increased collagen deposition (blue on trichrome). When anti-TNF-α therapy was begun on d1 after PG-PS injection, cecal tissue at d21 was not significantly different from that of HSA-injected animals. When anti-TNF-α therapy was begun on d7, submucosa and subserosa showed increased density due to collagen deposition and increased cellularity; the subserosa was expanded (double-headed arrow). When anti-TNF-α treatment was delayed until d14, findings were similar to those in tissue from PG-PS-injected/vehicle-treated animals described above: d14 anti-TNF-α treatment images at top shows disruption of the muscularis propria by granulomatous inflammation (brackets and arrow) and expansion of the submucosa and subserosa (double-headed arrows); images at bottom show loss of crypt architecture in the region of a large inflammatory cell infiltrate (brackets).

To help confirm administration of the anti-TNF-α to the appropriate animals, serum drug levels were measured in all animals at the end of each experiment. Due to the different treatment start dates and slightly different experimental end points, the elapsed time between the final dose of drug and the serum sampling varied (experiment 1, 72 h; experiment 2, 48 h; experiment 3, 24 h). Nevertheless, anti-TNF-α was readily detected in the serum samples from all of the anti-TNF-α-treated rats (Fig. 1D). In experiments 1 and 2, mean serum drug levels were greater in the HSA-injected than in the PG-PS-injected rats (3.7- and 2.0-fold, respectively; P = 0.012 for both). When the results for the three experiments were considered in aggregate, the significance of this difference was greater (2.1-fold; P = 0.0006). As expected, anti-TNF-α was not detectable in the serum of any of the vehicle-treated animals (lower limit of quantitation = 0.1 μg/ml).

Similar to humans with inflammatory processes, rats with PG-PS-induced enterocolitis (vehicle-treated) develop anemia, with decreased hematocrits compared with HSA-injected animals (1) (Fig. 1E; d1: 0.87-fold HSA-injected, P = 0.0001; d7: 0.84-fold, P = 0.03). Anti-TNF-α therapy begun d1 post-PG-PS injection attenuated the development of anemia (Fig. 1E: hematocrit 1.08-fold vehicle-treated, P = 0.02). However, when initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy was delayed until d7 or d14 post-PG-PS injection, hematocrits were reduced to the same level as in vehicle-treated PG-PS-injected animals (Fig. 1E; d7: 1.03-fold vehicle-treated, P = 0.81; d14: 0.99-fold, P = 0.96).

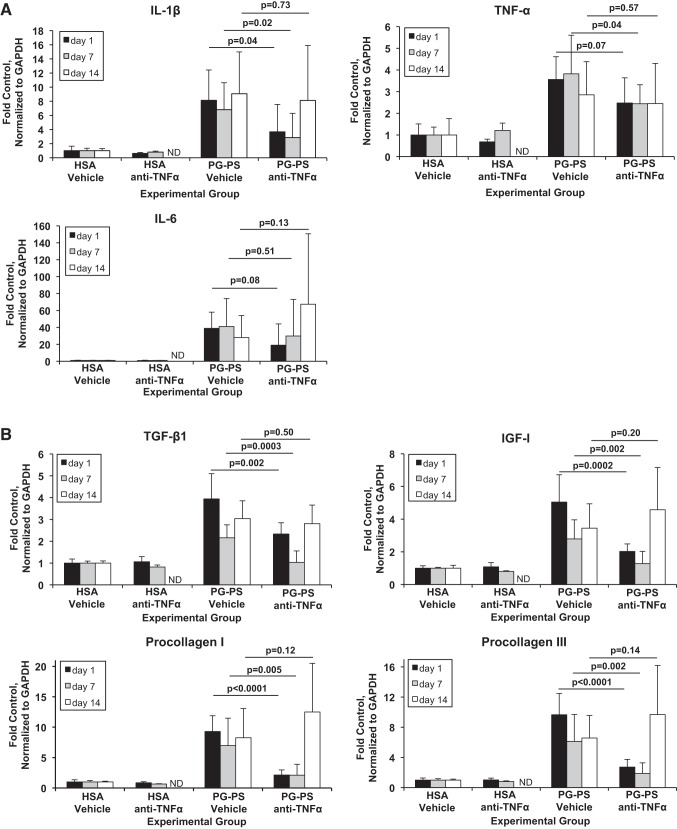

Levels of proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs measured by quantitative real-time PCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed as fold the mean of vehicle-treated HSA-injected controls are shown in Fig. 4A. IL-1β mRNA decreased in PG-PS-injected rats given anti-TNF-α beginning on d1 or d7 compared with vehicle-treated rats, but when treatment was begun on d14, there was no effect (d1: 0.45-fold vehicle-treated, P = 0.04; d7: 0.42-fold, P = 0.02; d14: 0.89-fold, P = 0.73). TNF-α mRNA varied in response to anti-TNF-α therapy when given at the different time points (d1: 0.69-fold vehicle-treated, P = 0.07; d7: 0.64-fold, P = 0.04; d14: 0.86-fold, P = 0.57). A rebound increase in TNF-α mRNA in response to anti-TNF-α therapy was not seen at any time point. IL-6 mRNA levels did not change significantly when anti-TNF-α therapy was begun at any time point studied (d1: 0.49-fold decrease vs. vehicle-treated, P = 0.08; d7: 0.73-fold decrease, P = 0.51 d14: 2.4-fold increase, P = 0.13).

Fig. 4.

Relative expression in cecal tissue of mRNAs of proinflammatory (A) and profibrotic (B) factors by quantitative real-time PCR. Expression is normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold the mean value for vehicle-treated HSA-injected control animals. Results shown are means; error bars reflect SD; n is as shown in Table 1. Comparisons were performed with one-way ANOVA and Sidak's post hoc.

Levels of mRNAs of profibrotic factors are shown in Fig. 4B. Levels of TGF-β1, IGF-I, procollagen I, and procollagen III mRNAs decreased in PG-PS-injected rats when anti-TNF-α treatment was begun on d1 or d7 compared with vehicle-treated rats but did not change when treatment was begun on d14 (TGF-β1; d1: 0.59-fold vehicle treated, P = 0.002; d7: 0.48-fold, P = 0.0003; d14: 0.93-fold, P = 0.50; IGF-I; d1: 0.40-fold vehicle treated, P = 0.0002; d7: 0.46-fold, P = 0.002; d14: 1.33-fold, P = 0.20; procollagen I; d1: 0.23-fold, P < 0.0001; d7: 0.30-fold, P = 0.005; d14: 1.51-fold, P = 0.12; and procollagen III; d1: 0.28-fold, P < 0.0001; d7: 0.31-fold, P = 0.002; d14: 1.47-fold, P = 0.14).

Untreated HSA- and PG-PS-injected rats were studied at d1 and d14 postinjection, the time points at which anti-TNF-α therapy had been shown to be efficacious or ineffective, respectively. At d1, the cecal wall was expanded in both HSA- and PG-PS-injected rats due to submucosal hemorrhage and edema (Fig. 5), consistent with acute injury. These changes were more marked in the PG-PS-injected rats. At d14, HSA-injected cecum was normal in appearance. In contrast, PG-PS-injected cecal wall was expanded, with inflammatory infiltrates in the submucosa and disrupting the broadened muscularis propria. Interestingly, in PG-PS-injected rats, the fold increases of cecal mRNA levels over those of nonoperated rats were similar at d1 and d14 for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Table 3). In contrast, levels of mRNA for the profibrotic factors TGF-β1, IGF-I, and procollagen types I and III were more greatly elevated at d14 than at d1 (2.2-, 2.2-, 10.1-, and 5.4-fold d1 values, respectively; P ≤ 0.02 for all).

Fig. 5.

Representative sections of cecal tissue from untreated HSA- or PG-PS-injected rats at d1 or d14 postinjection, stained with H&E (left) and trichrome (right). Original magnification: ×4. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Table 3.

Relative expression of profibrotic and proinflammatory factors in the PG-PS model

| Proinflammatory |

Profibrotic |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | IL-1β | IL-6 | TNF-α | TGF-β1 | IGF-I | Procollagen I | Procollagen III |

| d1 HSA | 1.80 | 1.41 | 3.63 | 1.31 | 1.81 | 1.55 | 1.84 |

| d1 PG-PS | 22.1 ± 6.8 | 93.4 ± 66.1 | 7.39 ± 3.22 | 2.25 ± 0.11 | 2.24 ± 0.43 | 0.60 ± 0.10 | 1.21 ± 0.05 |

| d14 HSA | 2.06 | 1.33 | 1.99 | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.07 | 1.19 |

| d14 PG-PS | 17.7 ± 4.5 | 81.1 ± 32.2 | 6.96 ± 2.46 | 5.05 ± 1.35* | 4.85 ± 0.49† | 6.07 ± 1.22† | 6.51 ± 1.67† |

Values are fold the mean nonoperated control level (n = 3) and are expressed as mean ± SD. HSA groups, n = 1; PG-PS groups, n = 3. Levels of mRNAs were normalized to that of GAPDH. Comparisons are between d14 and d1 PG-PS compared with Student's t-test.

P = 0.02

P ≤ 0.005.

DISCUSSION

The decision about when to initiate potent biologic therapy such as anti-TNF-α therapy in a patient with CD is made after consideration of many factors. Given the potential medication-related risks including life threatening infections and cancer, physicians and patients often prefer to delay initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy hoping that drugs with less risky side-effect profiles will be effective. However, data suggest that the disease is more responsive to anti-TNF-α therapy early in the disease course (23, 41). The mechanism of this change in responsiveness is not known. It is hypothesized that inflammation may not be TNF-α “driven” later in the disease course such that patients on long-term anti-TNF-α therapy may benefit from a switch to a drug with a different mechanism of action. With respect to fibrosis, it is assumed that later in the disease course the fibrosis may be already “fixed” and that even if inflammation is decreased, the fibrosis is already established and not likely to be changed when the therapy is initiated. The PG-PS model with its similar mechanism of action to the human disease, prominent inflammation and fibrosis, and reproducible and predictable course is ideal for studying therapeutic responsiveness. We recently demonstrated that the PG-PS model is responsive to anti-TNF-α therapy begun on postlaparotomy d1 (1), a prevention paradigm in which chronic inflammation and fibrosis have not yet begun. Here we demonstrate that the PG-PS model, like the human disease, is less responsive to anti-TNF-α therapy as the model progresses. This change in responsiveness to anti-TNF-α therapy is coincident with a major shift in the cytokine milieu, with increased expression of both proinflammatory and profibrotic factors observed on d14 in vehicle-treated PG-PS-injected rats. While not proven in this study, it is possible that the combined actions of key factors present at the time the medication is initiated determine the outcome. This hypothesis encompasses our accumulated knowledge of the pleotropic and redundant actions of cytokine networks in inflamed tissue. In the future of personalized medicine, determining the cytokine profile of the patient's tissue may help caregivers anticipate the response to therapy.

There was a stepwise loss of responsiveness when anti-TNF-α was begun on d7 and d14 compared with d1 that was seen in the decrease in gross abdominal score and histologic inflammation score in PG-PS-injected rats. This was associated with a diminished ability of anti-TNF-α therapy to suppress proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNAs. While induction by TNF-α may be a predominant mechanism underlying expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, knockout models have shown that IL-1β can be expressed independently (51). Therefore, blockade of TNF-α may still allow IL-1β activity to persist, an activity that includes induction of IL-6 (35) and IGF-I (20). It is possible that by d14 in the PG-PS model (and perhaps at some point in the course of CD) TNF-α is no longer the major determinant of IL-1β expression, rendering anti-TNF-α therapy less effective. Therefore, in our model, IL-6 and IGF-I, both highly expressed at later time points, could play a role in maintaining the inflammatory process.

Delayed onset of anti-TNF-α therapy failed to attenuate the PG-PS induction of TGF-β1 mRNA, likely contributing to the loss of efficacy in treating both the inflammatory and the fibrotic processes. TGF-β is necessary for Th17 lineage commitment and is also required for the induction of receptor expression necessary for induction of certain proinflammatory cytokines in Th17 cells (22). TGF-β1 appears to play a substantial role in CD-associated fibrosis and may do so by several mechanisms including: upregulation of expression of the downstream effector connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (3, 4, 24); induction of increased fibronectin, collagen I, and collagen III production (24, 42, 45); inhibition of extracellular matrix turnover through downregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and upregulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) (4, 25); and induction of transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts (42). In addition, TGF-β can perpetuate the fibrotic response in an autocrine manner after inflammation resolves (49). TGF-β1 is known to be important in the fibrotic response to PG-PS because neutralization of endogenous TGF-β1 in cultured neonatal Lewis rat intestinal myofibroblasts blocks PG-PS-induced collagen I gene expression by the cells (53). It should be noted that in our model, as in the human disease, anti-TNF-α may be better at decreasing inflammation than abrogating fibrosis. In our study, some measures of fibrosis were significantly decreased such as the score for adhesions and mesenteric fibrosis while others such as the histologic score for fibrosis demonstrated a trend that did was not reach statistical significance; persistent TGF-β1 expression could represent a mechanism for this observation.

IGF-I appears to be important in CD-associated fibrosis because it is increased in fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells of inflamed and fibrotic tissue from ileum and colon of CD patients but not in uninvolved tissue (11, 31, 58). IGF-I increases collagen I mRNA expression by and proliferation of cultured rat colonic smooth muscle cells, mouse intestinal myofibroblasts, and the human colonic fibroblast/myofibroblast cell line CCD-18Co (42, 48, 57) and also increases proliferation of human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts (17, 46). Paracrine and/or autocrine actions of locally produced IGF-I are thought to contribute to intestinal fibrosis in CD (47). Furthermore, IGF-I can enhance TGF-β activity by increasing MMP, which in turn can activate TGF-β1 by causing its dissociation from the latency-associated peptide LAP (55).

In animal models of fibrosis in other organ systems, anti-TNF-α has been shown to reduce fibrosis in lung (9) and liver (2), but in these studies anti-TNF-α therapy was initiated very early in the disease process, and the results may therefore not predict the response to anti-TNF-α therapy in advanced disease (9). Clinically, TNF-α antagonists have shown mixed results in the treatment of systemic sclerosis: some patients have had improved joint disease, improved skin fibrosis, and/or stabilization of pulmonary fibrosis, while others have had new development or fatal exacerbation of fibrosing alveolitis (9). Our data and others are consistent with a complex action of anti-TNF-α therapy on fibrosis that is related to the cytokine and growth factor milieu of the tissue involved.

It is well established that the biological effects of individual cytokines can vary considerably in the presence vs. the absence of other cytokines (14, 22, 30). If the cytokine milieu changes over the course of CD, the therapeutic efficacy of cytokines or cytokine-blocking therapies might be expected to differ over the course of the disease, as has been shown to occur in animal models. In the PG-PS model it has been shown that administration of IL-10 in a preventive paradigm, beginning 12 h before PG-PS injection, is effective in reducing intestinal inflammation, while IL-10 therapy delayed until d10-16 post-PG-PS injection is ineffective (15). A loss of responsiveness to cytokine blockade also occurs in a mouse model of ileitis as it progresses from acute to chronic disease (34). Loss of efficacy of TNF-α blockade with increasing duration of disease is known to occur in CD (23, 41). In vivo, differences in the complex cytokine milieu could be the basis for differential responses at different stages of disease (14, 22, 30). Additionally, the results of in vitro work where the cytokine milieu can be controlled suggest that differences in receptor expression, specifically increased TNFRII expression, could contribute to the differential response to TNF-α (and thus to anti-TNF-α) over time (48).

The luminal environment, specifically the microbiome, is another factor that may affect responsiveness to anti-TNF-α therapy. In IL-10 knockout mice (IL-10−/−), an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) model in which the microbiome and cage environment are important factors in determining the expression of colitis (19), the response to anti-TNF-α is variable. When begun in IL-10−/− mice at 4 wk of age, anti-TNF-α therapy was effective in limiting inflammation (40), and it was also effective in a separate study of treatment in older mice from 24 to 28 wk of age (13). However, other studies reported lack of efficacy in both early (3 wk of age) and intermediate duration (12 wk of age) disease (33). Variable results in animal models may be related to differences in background strain and drug dosage and administration schedule as well as animal age and disease stage. In pediatric IBD, it was recently shown that microbiota varied between areas of inflammation and noninflamed areas along the intestine (21). Additionally, those who responded to anti-TNF-α therapy showed improved microbial diversity and an increase in the abundance of particular bacterial species while nonresponders did not (21).

Finally, the observation of lower serum drug levels in PG-PS-injected animals compared with HSA-injected animals is most likely due to sequestration of drug in inflamed tissues or gut losses through the feces in areas of intestinal inflammation. In patients with IBD, severe inflammation is associated with lower than anticipated serum anti-TNF-α levels and this is felt to result at least partially from fecal losses (6, 36). We did not measure stool drug levels in our study; inflammation in the liver and intestine in the PG-PS treated animals could sequester significant drug.

In conclusion, we found that anti-TNF-α therapy decreased tissue inflammation and both proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine gene expression when given early but not late in the course of PG-PS-induced enterocolitis. Delayed administration of anti-TNF-α therapy was accompanied by progressive refractoriness to both anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of the drug. Thus our data support the use of anti-TNF-α therapy early in the course of the disease; use late in the disease process may not be effective and could increase profibrotic factors. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that the cytokine milieu present in the tissue at the time the anti-TNF-α therapy is begun determines the response to therapy. Thus our data are consistent with improved outcomes with anti-TNF-α therapy in patients with newly diagnosed disease and do not dispel the possibility that anti-TNF-α therapy could worsen fibrosis in some patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1RO1DK073992 to E. M. Zimmermann) and a grant from Abbvie (Abbott Park, IL) and funding through the University of Florida Gatorade Trust. Drug and vehicle were provided by Abbvie and serum drug level measurements were done by Abbvie personnel. Photomicrography was performed in the Microscopy and Image-analysis Laboratory (MIL) at the University of Michigan, Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, a facility supported by National Institutes of Health-National Cancer Institute, O'Brien Renal Center, University of Michigan Medical School, Endowment for the Basic Sciences (EBS), Department of Cell and Developmental Biology (CDB), and the University of Michigan. This work was also supported by the resources and facilities of the University of Michigan Gastrointestinal Peptide Research Center.

DISCLOSURES

E. M. Zimmermann has research grants and has performed consulting for Abbive, UCB Pharmaceuticals, and Bracco Diagnostics, Inc.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.S.-R., L.J.R., A.C.R., J.S.B., J.A., and E.M.Z. performed experiments; P.S.-R., L.J.R., C.S.B., A.C.R., J.S.B., and E.M.Z. analyzed data; P.S.-R. and E.M.Z. interpreted results of experiments; P.S.-R. and E.M.Z. drafted manuscript; L.J.R., C.S.B., A.C.R., J.S.B., J.A., S.R.O., and E.M.Z. edited and revised manuscript; C.S.B. and E.M.Z. prepared figures; E.M.Z. conception and design of research; E.M.Z. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Lazarus Mramba for assistance with the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler J, Rahal K, Swanson SD, Schmiedlin-Ren P, Rittershaus AC, Reingold LJ, Brudi JS, Shealy D, Cai A, McKenna BJ, Zimmermann EM. Anti-TNFα prevents bowel fibrosis assessed by mRNA, histology, & magnetization transfer MRI in rats with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19: 683–690, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahcecioglu IH, Koca SS, Poyrazoglu OK, Yalniz M, Ozercan IH, Ustundag B, Sahin K, Dagli AF, Isik A. Hepatoprotective effect of infliximab, an anti-TNF-α agent, on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic fibrosis. Inflammation 31: 215–221, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beddy D, Mulsow J, Watson RW, Fitzpatrick JM, O'Connell PR. Expression and regulation of connective tissue growth factor by transforming growth factor β and tumour necrosis factor α in fibroblasts isolated from strictures in patients with Crohn's disease. Br J Surg 93: 1290–1296, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biernacka A, Dobaczewski M, Frangogiannis NG. TGF-β signaling in fibrosis. Growth Factors 29: 196–202, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand S. Crohn's disease: Th1, Th17 or both? The change of a paradigm: new immunological and genetic insights implicate Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Gut 58: 1152–1167, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandse JF, van den Brink GR, Wildenberg ME, van der Kleij D, Rispens T, Jansen JM, Mathôt RA, Ponsioen CY, Löwenberg M, D'Haens GR. Loss of infliximab into feces is associated with lack of response to therapy in patients with severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 149: 350–355, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 140: 1785–1794, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Haens G, Van Deventer S, Van Hogezand R, Chalmers D, Kothe C, Baert F, Braakman T, Schaible T, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P. Endoscopic and histological healing with infliximab anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies in Crohn's disease: a European multicenter trial. Gastroenterology 116: 1029–1034, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Distler JH, Schett G, Gay S, Distler O. The controversial role of tumor necrosis factor α in fibrotic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 58: 2228–2235, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elson CO, Sartor RB, Tennyson GS, Riddell RH. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 109: 1344–1367, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn RS, Murthy KS, Grider JR, Kellum JM, Kuemmerle JF. Endogenous IGF-I and ανβ3 integrin ligands regulate increased smooth muscle hyperplasia in stricturing Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 138: 285–293, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia P, Schmiedlin-Ren P, Mathias JS, Tang H, Christman GM, Zimmermann EM. Resveratrol causes cell cycle arrest, decreased collagen synthesis, and apoptosis in rat intestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G326–G335, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gratz R, Becker S, Sokolowski N, Schumann M, Bass D, Malnick SD. Murine monoclonal anti-TNF antibody administration has a beneficial effect on inflammatory bowel disease that develops in IL-10 knockout mice. Dig Dis Sci 47: 1723–1727, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grotendorst GR, Rahmanie H, Duncan MR. Combinatorial signaling pathways determine fibroblast proliferationa and myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J 18: 469–479, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herfarth HH, Bocker U, Janardhanam R, Sartor RB. Subtherapeutic corticosteroids potentiate the ability of interleukin 10 to prevent chronic inflammation in rats. Gastroenterology 115: 856–865, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, Foster SJ, Moran AP, Fernandez-Luna JL, Nunez G. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2 Implications for Crohn's disease. J Biol Chem 278: 5509–5512, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jobson TM, Billington CK, Hall IP. Regulation of proliferation of human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts by mediators important in intestinal inflammation. J Clin Invest 101: 2650–2657, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamm MA, Ng SC, De Cruz P, Allen P, Hanauer SB. Practical application of anti-TNF therapy for luminal Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17: 2366–2391, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keubler LM, Buettner M, Häger C, Bleich A. A multihit model: colitis lessons from the interleukin-10-deficient mouse. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21: 1967–1975, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirstein M, Aston C, Hintz R, Vlassara H. Receptor-specific induction of insulin-like growth factor I in human monocytes by advanced glycosylation end product-modified proteins. J Clin Invest 90: 439–446, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolho KL, Korpela K, Jaakkola T, Pichai MV, Zoetendal EG MV, Salonen A, de Vos WM. Fecal microbiota in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and its relation to inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol 110: 921–930, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korn T, Bettelle E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 485–517, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kugathasan S, Werlin SL, Martinez A, Rivera MT, Heikenen JB, Binion DG. Prolonged duration of response to infliximab in early but not late pediatric Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 95: 3189–3194, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-β signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J 18: 816–827, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Kuemmerle JF. Mechanisms that mediate the development of fibrosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20; 1250–1258, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenstein GR, Olson A, Travers S, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Factors associated with the development of intestinal strictures or obstructions in patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 1030–1038, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-delta delta C(T)] method. Methods (Duluth) 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louis E, Boverie J, Dewit O, Baert F, De Vos M, D'Haens G; Belgian IBD Research Group . Treatment of small bowel subocclusive Crohn's disease with infliximab: an open pilot study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 70: 15–19, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi FA, Belaiche J. Behaviour of Crohn's disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut 49: 777–782, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, Tato CM, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Cua DJ. TGF-β and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain TH-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol 8: 1390–1397, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pucilowska JB, McNaughton KK, Mohapatra NK, Hoyt EC, Zimmermann EZ, Sartor RB, Lund PK. IGF-I and procollagen α1(I) are coexpressed in a subset of mesenchymal cells in active Crohn's disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G1307–G1322, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahal K, Schmiedlin-Ren P, Adler J, Dhanani M, Sultani V, Rittershaus AC, Reingold L, Zhu J, McKenna BJ, Christman GM, Zimmermann EM. Resveratrol has anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects in the peptidoglycan-polysaccharide rat model of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 18: 613–623, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rennick DM, Fort MM, Davidson NJ. Studies with IL-10−/− mice: an overview. J Leukoc Biol 61: 389–396, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivera-Nieves J, Ho J, Bamias G, Ivashkina N, Ley K, Oppermann M, Cominelli F. Antibody blockade of CCL25/CCR9 ameliorates early but not late chronic murine ileitis. Gastroenterology 131: 1518–1529, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogler G, Gelbmann CM, Vogl D, Brunner M, Schölmerich J, Falk W, Andrus T, Brand K. Differential activation of cytokine secretion in primary human colonic fibroblast/myofibroblast cultures. Scand J Gastroenterol 36: 389–398, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen MJ, Minar P, Vinks AA. Review article: applying pharmacokinetics to optimise dosing of anti-TNF biologics in acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 41: 1094–1103, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sands BE, Siegel CA. Crohn's Disease in Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management (10th ed). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, 2016, chapt. 115, p. 1990–2022. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sartor RB, Herfarth H, Van Tol EAF. Bacterial cell wall polymer-induced granulomatous inflammation. Methods 9: 233–247, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 3: 390–407, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheinin T, Butler DM, Salway F, Scallon B, Feldmann M. Validation of the interleukin-10 knockout mouse model of colitis: antitumour necrosis factor-antibodies suppress the progression of colitis. Clin Exp Immunol 133: 38–43, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Bloomfield R, Nikolaus S, Scholmerich J, Panes J, Sandborn WJ; PRECISE 2 Study Investigators. Increased response and remission rates in short-duration Crohn's disease with subcutaneous certolizumab pegol: an analysis of PRECiSE 2 randomized maintenance trial data. Am J Gastroenterol 105: 1574–1582, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simmons JG, Pucilowska JB, Keku TO, Lund PK. IGF-I and TGF-β1 have distinct effects on phenotype and proliferation of intestinal fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283: G809–G818, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sohrabpour AA, Malekzadeh R, Keshavarzian A. Current therapeutic approaches in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Des 16: 3368–3383, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorrentino D, Terrosu G, Vadala S, Avellini C. Fibrotic strictures and anti-TNF-alpha therapy in Crohn's disease. Digestion 75: 22–24, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stallmach A, Schuppan D, Riese HH, Matthes H, Riecken EO. Increased collagen type III synthesis by fibroblasts isolated from strictures of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 102: 1920–1929, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanzel RD, Lourenssen S, Nair DG, Blennerhassett MG. Mitogenic factors promoting smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C805–C817, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theiss AL, Fruchtman S, Lund PK. Growth factors in inflammatory bowel disease. The actions and interactions of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I. Inflamm Bowel Dis 10: 871–880, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Theiss AL, Simmons JG, Jobin C, Lund PK. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha increases collagen accumulation and proliferation in intestinal myofibroblasts via TNF receptor 2. J Biol Chem 280: 36099–36109, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodeling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 349–363, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toy LS, Scherl EJ, Kornbluth A, Marion JF, Greenstein AJ, Agus S, Gerson C, Fox N, Present DH. Complete bowel obstruction following initial response to infliximab therapy for Crohn's disease: a series of a newly described complication. Gastroenterology 118, Suppl 2: A569, 2000. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van den Berg WB. Joint inflammation and cartilage destruction may occur uncoupled. Springer Semin Immunopathol 20: 149–164, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Deventer SJ. Tumour necrosis factor and Crohn's disease. Gut 40: 443–448, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Tol EA, Holt L, Li FL, Kong FM, Rippe R, Yamauchi M, Pucilowska J, Lund PK, Sartor RB. Bacterial cell wall polymers promote intestinal fibrosis by direct stimulation of myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G245–G255, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vasilopoulos S, Kugathasan S, Saeian K, Emmons JE, Hogan WJ, Otterson MF, Telford GL, Bionion DG. Intestinal strictures complicating initially successful infliximab treatment for luminal Crohn's disease (Abstract). Am J Gastroenterol 95: 2503, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walsh LA, Damjanovski S. IGF-1 increases invasive potential of MCF 7 breast cancer cells and induces activation of latent TGF-β1 resulting in epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Commun Signal 9: 10, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 214: 199–210, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zimmermann EM, Li L, Hou YT, Cannon M, Christman GM, Bitar KN. IGF-I induces collagen and IGFBP-5 mRNA in rat intestinal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 273: G875–G882, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zimmermann EM, Li L, Hou YT, Mohapatra NK, Pucilowska JB. Insulin-like growth factor I and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 in Crohn's disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G1022–G1029, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zimmermann EM, Sartor RB, McCall RD, Pardo M, Bender D, Lund PK. Insulin-like growth factor I and interleukin 1β messenger RNA in a rat model of granulomatous enterocolitis and hepatitis. Gastroenterology 105: 399–409, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]