Abstract

Acetylcholine released from cholinergic nerves is involved in heat loss responses of cutaneous vasodilation and sweating. K+ channels are thought to play a role in regulating cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating, though which K+ channels are involved in their regulation remains unclear. We evaluated the hypotheses that 1) Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa), ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP), and voltage-gated K+ (KV) channels all contribute to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation; and 2) KV channels, but not KCa and KATP channels, contribute to cholinergic sweating. In 13 young adults (24 ± 5 years), cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) and sweat rate were evaluated at intradermal microdialysis sites that were continuously perfused with: 1) lactated Ringer (Control), 2) 50 mM tetraethylammonium (KCa channel blocker), 3) 5 mM glybenclamide (KATP channel blocker), and 4) 10 mM 4-aminopyridine (KV channel blocker). At all sites, cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating were induced by coadministration of methacholine (0.0125, 0.25, 5, 100, and 2,000 mM, each for 25 min). The methacholine-induced increase in CVC was lower with the KCa channel blocker relative to Control at 0.0125 (1 ± 1 vs. 9 ± 6%max) and 5 (2 ± 5 vs. 17 ± 14%max) mM methacholine, whereas it was lower in the presence of KATP (69 ± 7%max) and KV (57 ± 14%max) channel blocker compared with Control (79 ± 6%max) at 100 mM methacholine. Furthermore, methacholine-induced sweating was lower at the KV channel blocker site (0.42 ± 0.17 mg·min−1·cm−2) compared with Control (0.58 ± 0.15 mg·min−1·cm−2) at 2,000 mM methacholine. In conclusion, we show that KCa, KATP, and KV channels play a role in cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation, whereas only KV channels contribute to cholinergic sweating in normothermic resting humans.

Keywords: potassium channel, hyperpolarization, sweat secretion, thermoregulation

cutaneous vasodilation and sweating are important to maintain a stable core body temperature during heat stress in humans. Although both adrenergic and cholinergic sympathetic nerves innervate cutaneous vessels and sweat glands, cholinergic nerves primarily mediate cutaneous vasodilation and sweating during whole body heat stress via postsynaptic receptor activation induced by acetylcholine and/or neuropeptides (18, 40). As for acetylcholine, it activates muscarinic receptors and triggers signal transduction in the intracellular spaces, and K+ channels are involved in this process associated with the regulation of cutaneous vasodilation (2, 16) and sweating (38). Activation of K+ channels accompanies K+ efflux and thus hyperpolarization in the vascular smooth muscle cells, which reduces the intracellular Ca2+ bioavailability that results in vasodilation. In addition, hyperpolarization associated with the activation of K+ channels occurring in the sweat glands ensures an electrochemical driving force for Cl− efflux into the lumen side of sweat gland, facilitating the production of sweat. However, which type(s) of K+ channels are specifically involved in the regulation of cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating remains to be elucidated.

Studies have identified a role for Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) (2) and ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) (16) channels in the regulation of cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated whether voltage-gated K+ (KV) channels may also be involved in this response. Given that KV channels have been shown to modulate cholinergic vasodilation under in vitro conditions in nonhuman species (9, 13), they may also play an important role in humans under in vivo conditions. As for the cholinergic sweating, whereas an in vitro study by Shamsuddin et al. (38) showed that K+ channels modulate cholinergic sweating, they found no roles for a number of specific K+ channels including KCa, KATP, and KV (i.e., KV7.1) channels. However, they did not test all subtypes of KV channels, leaving the possibility that KV channels (other than KV7.1) may contribute to cholinergic sweating. Despite our growing knowledge on the role of K+ channels in the regulation of cholinergic sweating, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of the roles of KCa, KATP, and KV channels in cholinergic sweating under in vivo conditions in humans.

Thus the purpose of the present study was to evaluate roles of KCa, KATP, and KV channels in the regulation of cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating in resting normothermic humans in vivo. We evaluated the hypothesis that both KCa and KATP channels as well as KV channels contribute to the regulation of cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation, whereas only KV channels are involved in the regulation of cholinergic sweating. In the present study, as opposed to utilizing acetylcholine to induce cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating, we employed methacholine, which is a known acetylcholine mimetic. To minimize the effects of nicotinic receptor activation on the cutaneous vasodilatory and sweating response and to isolate the muscarinic response, we chose to use methacholine given that it primarily activates muscarinic receptors (as opposed to acetylcholine which can activate both muscarinic and nicotinic receptors) (32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

The current study was approved by the University of Ottawa Health Sciences and Science Research Ethics Board, which is in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers before their participation in the study.

Subjects.

Thirteen physically active young males participated in this study. Mean (±SD) body mass, height, and age for the participants were the following: 78.3 ± 14.0 kg, 1.75 ± 0.06 m, and 24 ± 5 yr, respectively. All subjects were screened on a separate day before participating in the experimental session. Participants with a history of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutations, skin disorders, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, autonomic disorders, and/or cigarette smoking were excluded from the study. No subjects were taking prescription medications.

Experimental design.

All subjects were instructed to abstain from taking over-the-counter medications (including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and vitamins) for at least 48 h before the experimental session, as well as alcohol and caffeine consumption at least 12 h prior. Subjects refrained from performing intense exercise the day before the study. On the day of the experiment, participants were restricted from consuming food 2 h before and throughout the study. We did not control for the start time of the experiment; however, there was no clear difference in the pattern of response between the morning and afternoon period of the day. Upon arrival, the subjects voided their bladder, thereafter body mass was measured using a digital weight scale platform (model CBU150X, Mettler Toledo, OH) with a weighing terminal (model IND560, Mettler Toledo). The subject's body height was also measured using an eye-level physician stadiometer (model 2391, Detecto Scale, Webb City, MO). Subjects were then seated in a semi-recumbent position in a thermoneutral room (∼23°C) and equipped with four intradermal microdialysis fibers (30 kDa cutoff, 10 mm membrane) (MD2000, Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN) placed on the dorsal side of the left forearm within the dermal layer of the skin. With the use of aseptic technique, a 25-gauge needle was first inserted into the unanesthetized skin and then a microdialysis fiber was threaded through the lumen of the needle. The needle was subsequently withdrawn leaving only the fiber in place. The entry and exit points for the fibers were separated by ∼2.5 cm with a separation of 4.0 cm between the four fiber insertion points. All fibers were then secured with surgical tape.

Approximately 10 min after the completion of fiber insertion, the four microdialysis fibers were continuously perfused with 1) lactated Ringer (Control, Baxter, Deerfield, IL), 2) 50 mM tetraethylammonium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), a nonspecific KCa channel blocker, 3) 5 mM glybenclamide (Sigma-Aldrich), a specific KATP channel blocker, and 4) 10 mM 4-aminopyridine (Sigma-Aldrich), a nonspecific KV channel blocker. The concentrations of tetraethylammonium (3, 4, 22, 24) and glybenclamide (22) were determined based on previous studies in which an intradermal microdialysis fiber was implanted in human skin. A previous study confirmed that intradermal administration of 50 mM tetraethylammonium via microdialysis specifically targets KCa channels with minimal influence on other K+ channels (3). We did not use specific large conductance KCa channel blockers such as charybdotoxin and iberiotoxin as they are toxic to humans (33). The concentration of 4-aminopyridine (10 mM) was determined based on our pilot work wherein concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 mM of 4-aminopyridine were tested. We found that ≥20 mM of 4-aminopyridine caused numbness and/or tingling as well as higher basal cutaneous blood flow, which were sustained >2 h after the initiation of 4-aminopyridine infusion. We determine that 10 mM of 4-aminopyridine is the highest dose that can be used without inducing some degree of numbness and tingling in the local skin area. While 10 mM of 4-aminopyridine caused a higher cutaneous blood flow in the present study, this response subsided with a prolonged (i.e., 82 ± 3 min) resting period before the start of the experimental phase of the protocol. To dissolve water-insoluble glybenclamide into lactated Ringer solution, we needed to add dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich) and sodium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich), resulting in a final solution with 5% dimethyl sulfoxide and a pH of 11. To account for the slight increase in baseline cutaneous blood flow associated with dimethyl sulfoxide (4, 20, 39) as well as the potential influence of dimethyl sulfoxide and higher pH (11) on cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating responses, all four solutions (Control, tetraethylammonium, glybenclamide, and 4-aminopyridine) were dissolved in lactated Ringer containing 5% dimethyl sulfoxide with the pH adjusted to 11. Each drug was continuously perfused at a rate of 4.0 μl/min using a microinfusion pump (model 4004, CMA Microdialysis, Solna, Sweden). Perfusion continued for the entire experimental protocol until the procedure for maximal cutaneous vasodilation began (see below).

After the 82 ± 3 min resting period of each K+ channel blocker administration, 10 min of baseline data (Baseline) was collected. Subsequently, each microdialysis fiber was perfused with methacholine (Sigma-Aldrich) in an ascending manner with five different concentrations of 0.0125, 0.25, 5, 100, and 2,000 mM at a rate of 4.0 μl/min (each for 25 min) in combination with the site-specific pharmacological agents with 5% dimethyl sulfoxide and a pH of 11. After the last infusion of methacholine (2,000 mM) was completed, 50 mM of sodium nitroprusside (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered at each microdialysis site at a rate of 6.0 μl/min until a stable plateau for cutaneous blood flow was achieved, which we defined as maximal cutaneous blood flow (20–30 min). Occasionally, the increase in cutaneous blood flow during methacholine administration (i.e., 5-2,000 mM) was greater than that achieved by sodium nitroprusside, which is in accordance with previous reports (10, 23). In that case, the highest cutaneous blood flow during methacholine administration was considered as maximal cutaneous blood flow.

Measurements.

Cutaneous red blood cell flux (expressed in perfusion units) was locally measured as an index of cutaneous blood flow at a sampling rate of 32 Hz using laser-Doppler flowmetry (PeriFlux System 5000, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden). Integrated laser-Doppler flowmetry probes with a 7-laser array (model 413, Perimed) were housed in the center of each sweat capsule over each microdialysis fiber for simultaneous measurement of both local forearm sweat rate and cutaneous red blood cell flux. Manual auscultation was performed using a mercury column sphygmomanometer (Baumanometer Standby model, WA Baum, Copiague, NY) to obtain blood pressures every 10–15 min. Mean arterial pressure was calculated from diastolic arterial pressure plus one-third the difference between systolic and diastolic pressures (i.e., pulse pressure). Cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) was evaluated as cutaneous red blood cell flux divided by mean arterial pressure.

A sweat capsule covering an area of 1.1 cm2 specifically designed for use with an intradermal microdialysis probe (27) was placed directly over the center of each microdialysis membrane. The sweat capsules were secured to the skin with adhesive rings and topical skin glue (Collodion HV, Mavidon Medical products, Lake Worth, FL). Dry compressed air in gas tanks located in the thermoneutral room (∼23°C) was supplied to each capsule at a rate of 0.20 l/min, while water content of the effluent air from the sweat capsule was measured with high-precision dew point mirrors (model 473, RH systems, Albuquerque, NM). Long vinyl tubes were used for connections between the gas tank and the sweat capsule, and between the sweat capsule and the dew point mirror. Local forearm sweat rate was measured continuously (5 s sampling rate) and calculated from the difference in water content between influent and effluent air multiplied by the flow rate and normalized for the skin surface area under the capsule (mg·min−1·cm−2).

Data analysis.

CVC data were presented in maximal percent (%max), which minimizes the effect of site-to-site heterogeneity at the level of cutaneous blood flow (29). Maximal absolute CVC, which is used to calculate %max, was obtained during sodium nitroprusside administration or during higher doses of methacholine administration. All values used for data analysis (CVC and sweat rate) were obtained by averaging values over the last 5 min of each stage (i.e., Baseline, 0.0125, 0.25, 5, 100, 2,000 mM of methacholine). We calculated the change (Δ) in CVC and sweat rate from Baseline to each methacholine concentration. We also evaluated the highest ΔCVC and Δsweat rate achieved throughout methacholine administration protocol (defined as Peak). Furthermore, ΔCVC from 100 to 2,000 mM of methacholine administration was evaluated at each site.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical tests were performed using the software package SPSS 23 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY). ΔCVC (%max) and Δsweat rate (mg·min−1·cm−2) from Baseline were analyzed using a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance with repeated factors of treatment site (four levels: Control, KCa channel blocker, KATP channel blocker, KV channel blocker) and stage (seven levels: Baseline, 5 doses of methacholine, Peak). One-way repeated measures analysis of variance was employed to analyze CVC (%max) and sweat rate (mg·min−1·cm−2) obtained at Baseline as well as maximal absolute CVC (perfusion units/mmHg) with a repeated factor of treatment site (four levels: Control, KCa channel blocker, KATP channel blocker, KV channel blocker). When a significant interaction or main effect was detected, post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted using the Student's paired two-tailed t-tests. P values for the multiple comparisons were adjusted using a modified Bonferroni test (i.e., Hochberg's procedure) (15). The level of significance for all analyses was set at P ≤ 0.05. All values are reported with a mean ± 95% confidence interval. The confidence intervals at 95% were calculated as 1.96 × means ± SE.

RESULTS

Baseline.

The administration of the KCa channel blocker reduced CVC relative to Control (Fig. 1A). However, when compared with Control, no effect on sweating was measured for any of the K+ channel blocked sites (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Cutaneous vascular conductance (A) and sweat rate (B) measured at Baseline. Data are presented as means ± 95% confidence interval. The four intradermal forearm sites were perfused with either 1) lactated Ringer (Control), 2) a nonspecific Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channel blocker, 3) a selective ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel blocker, or 4) a nonspecific voltage-gated K+ (KV) channel blocker. No between-site difference in sweat rate was observed (P = 0.33 for a main effect of treatment site).

During methacholine administration.

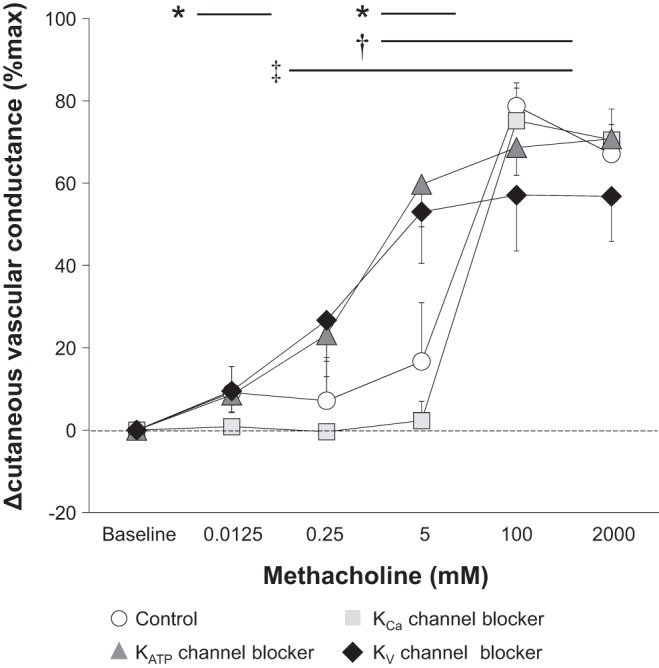

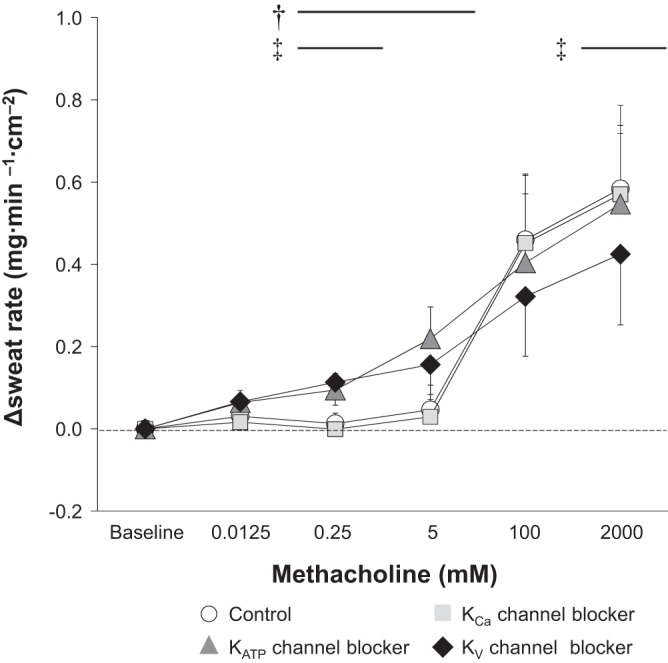

When compared with the Control, the KCa channel blocker attenuated ΔCVC at 0.0125 and 5 mM of methacholine, whereas KATP and KV channel blockers decreased ΔCVC at 100 mM of methacholine only (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the KV channel blocker attenuated Δsweat rate at 2,000 mM of methacholine relative to Control (Fig. 3). The infusion of the KV channel blocker also attenuated ΔCVC and Δsweat rate assessed at Peak compared with Control (Fig. 4). Finally, KATP and KV channel blockers augmented ΔCVC and Δsweat rate measured at 0.25 and/or 5 mM of methacholine (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Change (Δ) in cutaneous vascular conductance from Baseline to each dose of methacholine. Data are presented as means ± 95% confidence interval. The four intradermal forearm sites were perfused with either 1) lactated Ringer (Control), 2) a nonspecific Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channel blocker, 3) a selective ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel blocker, or 4) a nonspecific voltage-gated K+ (KV) channel blocker. *Control vs. KCa channel blocker (P ≤ 0.05); †Control vs. KATP channel blocker (P ≤ 0.05); ‡Control vs. KV channel blocker (P ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Change (Δ) in sweat rate from Baseline to each dose of methacholine. Data are presented as means ± 95% confidence interval. The four intradermal forearm sites were perfused with either 1) lactated Ringer (Control), 2) a nonspecific Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channel blocker, 3) a selective ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel blocker, or 4) a nonspecific voltage-gated K+ (KV) channel blocker. †Control vs. KATP channel blocker (P ≤ 0.05); ‡Control vs. KV channel blocker (P ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Change (Δ) in cutaneous vascular conductance (A) and sweat rate (B) from Baseline to Peak observed during methacholine administration. Data are presented as means ± 95% confidence interval. The four intradermal forearm sites were perfused with either 1) lactated Ringer (Control), 2) a nonspecific Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channel blocker, 3) a selective ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel blocker, or 4) a nonspecific voltage-gated K+ (KV) channel blocker.

During 100 mM of methacholine administration, CVC at the Control site reached ∼80%max, which subsequently decreased during 2,000 mM of methacholine administration (Fig. 5). However, this reduction in CVC was not observed when each K+ channel was simultaneously blocked (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Change (Δ) in cutaneous vascular conductance from 100 to 2,000 mM of methacholine administration. Data are presented as means ± 95% confidence interval. There are four intradermal sites perfused with either 1) lactated Ringer (Control), 2) a nonspecific Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channel blocker, 3) a selective ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel blocker, or 4) a nonspecific voltage-gated K+ (KV) channel blocker. Each P value is for the difference between 100 and 2,000 mM of methacholine.

Maximal absolute CVC.

Maximal absolute CVC (perfusion units/mmHg) was comparable between the four sites (Control, 1.46 ± 0.28; KCa channel blocker, 1.57 ± 0.33; KATP channel blocker, 1.37 ± 0.22; KV channel blocker, 1.23 ± 0.18) (P = 0.30 for a main effect of treatment site).

DISCUSSION

We show that KCa and KATP channels contribute to cholinergic cutaneous blood flow regulation, which is in accordance with previous reports. Importantly, we are the first to demonstrate that KV channels also play an important role in the cholinergic regulation of cutaneous perfusion, whereas only the KV channels modulate the cholinergic sweating response in normothermic resting humans.

Cutaneous vascular response.

Our findings demonstrate that KV channels do not modulate basal cutaneous vascular tone (i.e., as assessed during the Baseline period) under normothermic conditions (Fig. 1A). By contrast, consistent with previous studies (4, 11), we confirmed the contribution of KCa channels in defining basal cutaneous vascular tone (Fig. 1A). In contrast to a previous report by Hojs et al. (16), we did not observe a role for KATP channels in this response (Fig. 1A). However, given the reported contribution of KATP channels to basal vascular tone is relatively small (∼10%) under a normothermic state, we can generally conclude that KATP channels do not have a major role in the regulation of basal cutaneous vascular tone.

A key finding of our study was the observation that KV channels contribute to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation elicited by 100 mM of methacholine (Fig. 2). Since KV channels also contribute to CVC observed at Peak (Fig. 4A), KV channels appear to have an important role in mediating higher levels of skin perfusion (e.g., ∼80%max of CVC as presented in Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we also show that both KCa (at 0.0125 and 5 mM of methacholine) and KATP (at 100 mM of methacholine) channels contribute to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation (Fig. 2). These findings for KCa and KATP channels are consistent with previous studies using acetylcholine (2, 16). Taken together, our findings demonstrate that KCa, KATP, and KV channels are important factors in the regulation of cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation in normothermic resting humans. In general, K+ channels are located on the vascular smooth muscle cells, and their activation induces hyperpolarization and a reduction of intracellular Ca2+ bioavailability thereby inducing vasorelaxation. Some K+ channels are also present on the vascular endothelial cells (e.g., small and intermediate conductance KCa channels), and hyperpolarization associated with the activation of endothelial K+ channels can spread from the endothelium to vascular smooth muscle cells via gap junctions, thereby resulting in vasodilation (12, 26). Also, activation of endothelial K+ channels causes K+ efflux into the extracellular space, which in turn can activate Na+-K+-ATPase and/or inwardly rectifying K+ channels ultimately causing hyperpolarization of vascular smooth muscle cells and therefore vasodilation (7, 12, 31). Further studies are required to elucidate the precise locations of each K+ channel subtype in human cutaneous vessels and how each K+ channel contributes to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation.

At the Control site, a decline in CVC was measured between 100 to 2,000 mM of methacholine infusion despite an increase in cholinergic stimulation (Figs. 2 and 5), a pattern of response that we have previously observed (10, 14). This response appears not to be associated with nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase, as we previously showed that inhibition of both nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase did not influence the attenuation (10). However, in the current study, the decline of CVC from 100 to 2,000 mM of methacholine was abolished when blocking either KCa, KATP, or KV channels (Fig. 5). Thus, taken together, it is plausible to conclude that this aforementioned attenuation of cutaneous vasodilation may be related to a deactivation of K+ channels, which causes depolarization associated with reduced K+ efflux, ultimately resulting in vasoconstriction.

Although our results suggest roles of KCa, KATP, and KV channels in the regulation of cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation, a large portion of cutaneous vasodilation observed during high doses of methacholine administration (100 and 2,000 mM) was induced independently of these channels (Figs. 2 and 4A). Thus other factor(s) is/are likely involved. Indeed, we previously showed that nitric oxide synthase, but not cyclooxygenase, contributes to methacholine-induced cutaneous vasodilation (10). It is possible that K+ channel-dependent cutaneous vasodilation observed during cholinergic stimulation may be in part or in whole induced by nitric oxide produced from nitric oxide synthase, as nitric oxide can activate several K+ channels including KCa (1, 30), KATP (16), and KV (17) channels. However, this potential mechanism requires further evaluation.

Sweating.

K+ is known to be involved in electrolyte transport within the sweat duct (34, 35). Furthermore, the importance of K+ channels for cholinergic sweating has been demonstrated in vitro (38). However, until the present study, the specific K+ channels responsible for cholinergic sweating had not been examined. In this study, we show for the first time that KV channels contribute to cholinergic sweating in humans in vivo (Figs. 3 and 4B). Recently, an in vitro study by Shamsuddin et al. (38) reported that KV7.1 (one of the many KV channels) did not influence cholinergic sweating. Thus other KV channels are likely involved in cholinergic sweating in humans in vivo such as KV1, KV2, and/or KV3. Future studies are required to establish their respective roles.

Our novel observation of a role for KV channels in the regulation of sweating provides important insight into how cholinergic sweating occurs. During muscarinic receptor activation by cholinergic agent, depolarization occurs in the sweat gland (36), which may be associated with increases in intracellular Ca2+ through inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent mechanisms (21) or Ca2+ influx (28). This depolarization may activate KV channels, causing hyperpolarization associated with K+ efflux, ensuring an electrochemical driving force for Cl− efflux into the lumen side of sweat gland. This Cl− efflux can subsequently cause depolarization, which can activate KV channels, allowing continuous Cl− efflux and thus sweat secretion separately and/or in collaboration with other important factors including Na-K-Cl cotransporter and Na+-K+-ATPase.

We also found that blocking KCa and KATP channels did not attenuate methacholine-induced sweating (Fig. 3), which indicates that cholinergic sweating is not mediated via the activation of these channels. This is consistent with previous in vitro findings by Shamsuddin et al. (38). However, given that Ca2+ has been shown to be a key ion mediating sweat secretion both in vitro (37) and in vivo (28), it would seem counterintuitive that we showed no role of KCa channels. It is possible that increases in Ca2+ during cholinergic activation contribute to sweat secretion through K+ channel-independent pathways. As proposed by Wilson et al. (41), Ca2+ may play a role in sweat secretion through Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. In support of this mechanism, a recent study by Ertongur-Fauth et al. (8) revealed that one of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, anoctamin 1 (ANO1), also known as transmembrane member 16A (TMEM16A), appears to be involved in the Ca2+-dependent Cl− secretion in the human sweat gland in vitro. In addition, another Ca2+-activated Cl− channel, bestrophin 2 (Best 2), has been shown to contribute to sweat secretion as demonstrated in a mice model in vivo (6).

Considerations.

We employed a solution containing 5% dimethyl sulfoxide with a pH of 11 to dissolve glybenclamide, a water-insoluble compound. We do not know how this adjustment made to the glybenclamide solution influenced cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating. However, by design, all solutions used in the current study had 5% dimethyl sulfoxide and a pH of 11. Therefore, any difference in CVC and sweat rate observed in the present study appears to be due to the blockade of the various specific K+ channels.

As a first step, we evaluated a single role of each K+ channel in cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating. We do not know if and how K+ channels interact with other pathways in mediating cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating. Previous studies have shown that nitric oxide synthase contributes to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation (10) and that Ca2+ is involved in cholinergic sweating (28). Elucidating the potential interactions between K+ channels and other pathways (e.g., nitric oxide synthase, Ca2+) is an important next step.

Unexpectedly, ΔCVC and Δsweat rate in response to lower doses of methacholine (0.25 and 5 mM) were higher at the sites treated with KATP or KV channel blockade compared with the Control site (Figs. 2 and 3). We do not know the exact mechanism(s) underpinning this response, but blockade of KATP or KV channels might sensitize muscarinic receptors located on both cutaneous vessels and sweat glands, augmenting cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation and sweating. While this is an interesting observation, further studies are required to advance our understanding of the physiological implication of this response.

Perspectives and Significance

Human eccrine sweating during heat stress is governed exclusively by the sympathetic cholinergic system (5, 19, 25). Thus our observations of an involvement of KV channels in cholinergic sweating support a role for KV channels in thermal sweating. In addition, cholinergic mechanisms contribute to changes in cutaneous vascular tone during whole body heat stress (19). As such, our results demonstrating that KCa, KATP, and KV channels contribute to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation support the possibility that these K+ channels may also contribute to cutaneous vasodilation as elicited by whole body heating. Future studies evaluating if, and the extent to which, each K+ channel contributes to cutaneous vasodilation and sweating during heat stress are warranted.

In conclusion, we show that KCa, KATP, and KV channels all contribute to cholinergic cutaneous vasodilation, whereas KV channels contribute to cholinergic sweating in normothermic resting humans.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discover grant, RGPIN-06313-2014 and Discovery Grants Program-Accelerator Supplement, RGPAS-462252-2014; funds held by G. P. Kenny). G. P. Kenny was supported by a University of Ottawa Research Chair Award. N. Fujii was supported by the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit. J. C. Louie was supported by a Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology. S. Y. Zhang was supported by an NSERC Undergraduate Student Research Award.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.F. and G.P.K. conception and design of research; N.F., J.C.L., B.D.M., S.Y.Z., and M.-A.T. performed experiments; N.F. analyzed data; N.F., J.C.L., B.D.M., S.Y.Z., M.-A.T., and G.P.K. interpreted results of experiments; N.F. prepared figures; N.F. drafted manuscript; N.F., J.C.L., B.D.M., S.Y.Z., M.-A.T., and G.P.K. edited and revised manuscript; N.F., J.C.L., B.D.M., S.Y.Z., M.-A.T., and G.P.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the volunteers for taking their time to participate in this study. We also thank Jessica Elizabeth Szlapinski for her assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bae H, Lee HJ, Kim K, Kim JH, Kim T, Ko JH, Bang H, Lim I. The stimulating effects of nitric oxide on intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in human dermal fibroblasts through PKG pathways but not the PKA pathways. Chin J Physiol 57: 137–151, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunt VE, Fujii N, Minson CT. Endothelial-derived hyperpolarization contributes to acetylcholine-mediated vasodilation in human skin in a dose-dependent manner. J Appl Physiol (1985) 119: 1015–1022, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunt VE, Fujii N, Minson CT. No independent, but an interactive, role of calcium-activated potassium channels in human cutaneous active vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 1290–1296, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunt VE, Minson CT. KCa channels and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids: major contributors to thermal hyperaemia in human skin. J Physiol 590: 3523–3534, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buono MJ, Gonzalez G, Guest S, Hare A, Numan T, Tabor B, White A. The role of in vivo beta-adrenergic stimulation on sweat production during exercise. Auton Neurosci 155: 91–93, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui CY, Childress V, Piao Y, Michel M, Johnson AA, Kunisada M, Ko MS, Kaestner KH, Marmorstein AD, Schlessinger D. Forkhead transcription factor FoxA1 regulates sweat secretion through Bestrophin 2 anion channel and Na-K-Cl cotransporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 1199–1203, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dora KA, Garland CJ. Properties of smooth muscle hyperpolarization and relaxation to K+ in the rat isolated mesenteric artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2424–H2429, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ertongur-Fauth T, Hochheimer A, Buescher JM, Rapprich S, Krohn M. A novel TMEM16A splice variant lacking the dimerization domain contributes to calcium-activated chloride secretion in human sweat gland epithelial cells. Exp Dermatol 23: 825–831, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrer M, Marín J, Encabo A, Alonso MJ, Balfagón G. Role of K+ channels and sodium pump in the vasodilation induced by acetylcholine, nitric oxide, and cyclic GMP in the rabbit aorta. Gen Pharmacol 33: 35–41, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii N, McGinn R, Paull G, Stapleton JM, Meade RD, Kenny GP. Cyclooxygenase inhibition does not alter methacholine-induced sweating. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 1055–1062, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii N, Meade RD, Minson CT, Brunt VE, Boulay P, Sigal RJ, Kenny GP. Cutaneous blood flow during intradermal NO administration in young and older adults: roles for calcium-activated potassium channels and cyclooxygenase? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R1081–R1087, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garland CJ, Dora KA. EDH: Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and microvascular signaling. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2016 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/apha.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta PK, Subramani J, Leo MD, Sikarwar AS, Parida S, Prakash VR, Mishra SK. Role of voltage-dependent potassium channels and myo-endothelial gap junctions in 4-aminopyridine-induced inhibition of acetylcholine relaxation in rat carotid artery. Eur J Pharmacol 591: 171–176, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halili L, Singh MS, Fujii N, Alexander LM, Kenny GP. Endothelin-1 modulates methacholine-induced cutaneous vasodilatation but not sweating in young human skin. J Physiol 594: 3439–3452, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75: 800–802, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hojs N, Strucl M, Cankar K. The effect of glibenclamide on acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside induced vasodilatation in human cutaneous microcirculation. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 29: 38–44, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irvine JC, Favaloro JL, Kemp-Harper BK. NO- activates soluble guanylate cyclase and Kv channels to vasodilate resistance arteries. Hypertension 41: 1301–1307, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson JM, Minson CT, Kellogg DL Jr. Cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor mechanisms in temperature regulation. Compr Physiol 4: 33–89, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellogg DL Jr, Pérgola PE, Piest KL, Kosiba WA, Crandall CG, Grossmann M, Johnson JM. Cutaneous active vasodilation in humans is mediated by cholinergic nerve cotransmission. Circ Res 77: 1222–1228, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellogg DL Jr, Zhao JL, Wu Y. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase control mechanisms in the cutaneous vasculature of humans in vivo. J Physiol 586: 847–857, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klar J, Hisatsune C, Baig SM, Tariq M, Johansson ACV, Rasool M, Malik NA, Ameur A, Sugiura K, Feuk L, Mikoshiba K, Dahl N. Abolished InsP3R2 function inhibits sweat secretion in both humans and mice. J Clin Invest 124: 4773–4780, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kutz JL, Greaney JL, Santhanam L, Alexander LM. Evidence for a functional vasodilatatory role for hydrogen sulphide in the human cutaneous microvasculature. J Physiol 593: 2121–2129, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K, Mack GW. Role of nitric oxide in methacholine-induced sweating and vasodilation in human skin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 100: 1355–1360, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenzo S, Minson CT. Human cutaneous reactive hyperaemia: role of BKCa channels and sensory nerves. J Physiol 585: 295–303, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machado-Moreira CA, McLennan PL, Lillioja S, van Dijk W, Caldwell JN, Taylor NAS. The cholinergic blockade of both thermally and non-thermally induced human eccrine sweating. Exp Physiol 97: 930–942, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mather S, Dora KA, Sandow SL, Winter P, Garland CJ. Rapid endothelial cell-selective loading of connexin 40 antibody blocks endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor dilation in rat small mesenteric arteries. Circ Res 97: 399–407, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meade RD, Louie JC, Poirier MP, McGinn R, Fujii N, Kenny GP. Exploring the mechanisms underpinning sweating: the development of a specialized ventilated capsule for use with intradermal microdialysis. Physiol Rep 4: e12738, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metzler-Wilson K, Sammons DL, Ossim MA, Metzger NR, Jurovcik AJ, Krause BA, Wilson TE. Extracellular calcium chelation and attenuation of calcium entry decrease in vivo cholinergic-induced eccrine sweating sensitivity in humans. Exp Physiol 99: 393–402, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minson CT. Thermal provocation to evaluate microvascular reactivity in human skin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109: 1239–1246, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyoshi H, Nakaya Y. Endotoxin-induced nonendothelial nitric oxide activates the Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26: 1487–1495, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C799–C822, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pappano AJ. Cholinoceptor-activating & cholinesterase-inhibiting drugs. In: Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (12 th ed.) edited by Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2011, p. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickkers P, Hughes AD, Russel FG, Thien T, Smits P. Thiazide-induced vasodilation in humans is mediated by potassium channel activation. Hypertension 32: 1071–1076, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Cytosolic potassium controls CFTR deactivation in human sweat duct. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C122–C129, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Intracellular potassium activity and the role of potassium in transepithelial salt transport in the human reabsorptive sweat duct. J Membr Biol 119: 199–210, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato K, Ohtsuyama M, Sato F. Whole cell K and Cl currents in dissociated eccrine secretory coil cells during stimulation. J Membr Biol 134: 93–106, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato K, Sato F. Role of calcium in cholinergic and adrenergic mechanisms of eccrine sweat secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 241: C113–C120, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shamsuddin AK, Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Iontophoretic beta-adrenergic stimulation of human sweat glands: possible assay for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activity in vivo. Exp Physiol 93: 969–981, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shastry S, Joyner MJ. Geldanamycin attenuates NO-mediated dilation in human skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H232–H236, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith CJ, Johnson JM. Responses to hyperthermia. Optimizing heat dissipation by convection and evaporation: Neural control of skin blood flow and sweating in humans. Auton Neurosci 196: 25–36, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson TE, Metzler-Wilson K. Sweating chloride bullets: understanding the role of calcium in eccrine sweat glands and possible implications for hyperhidrosis. Exp Dermatol 24: 177–178, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]