Nrf2 is critical for mediating an antioxidant defense against oxidative insults. Emerging evidence has implicated Nrf2 in the regulation of mitochondrial function in some cell types, but no research has been devoted to understanding its contribution to exercise performance and mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle. Our work is the first to show that the presence of Nrf2 has an impact on muscle endurance performance and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle.

Keywords: mitochondrial biogenesis, exercise, endurance training, contractile properties, endurance performance

Abstract

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcription factor that confers cellular protection by upregulating antioxidant enzymes in response to oxidative stress. However, Nrf2 function within skeletal muscle remains to be further elucidated. We examined the role of Nrf2 in determining muscle phenotype using young (3 mo) and older (12 mo) Nrf2 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice. Basally, the absence of Nrf2 did not impact mitochondrial content. In intermyofibrillar mitochondria, lack of Nrf2 resulted in a 40% reduction in state 4 respiration, which coincided with a 68% increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) emission. Nrf2 abrogation impaired in situ muscle performance, characterized by a 48% greater rate of fatigue and a 35% decrease in force within the first 5 min of stimulation. Acute treadmill exercise resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in Nrf2 activation via enhanced DNA binding in WT animals. In response to training, cytochrome-c oxidase activity increased by 20% in the WT animals; however, this response was attenuated in KO mice. Nrf2 protein was reduced 30% by training. Despite this, exercise training normalized respiration, ROS production, and muscle performance in KO mice. Our results suggest that Nrf2 transcriptional activity is increased by exercise and that Nrf2 is required for the maintenance of basal mitochondrial function as well as for the normal increase in specific mitochondrial proteins in response to training. Nonetheless, the decrements in mitochondrial function in Nrf2 KO muscle can be rescued by exercise training, suggesting that this restorative function operates via a pathway independent of Nrf2.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Nrf2 is critical for mediating an antioxidant defense against oxidative insults. Emerging evidence has implicated Nrf2 in the regulation of mitochondrial function in some cell types, but no research has been devoted to understanding its contribution to exercise performance and mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle. Our work is the first to show that the presence of Nrf2 has an impact on muscle endurance performance and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle.

eukaryotic organisms are constantly challenged by an array of both endogenous and exogenous insults that can alter the redox balance of the cell. Therefore, to combat these insults, cells have evolved an elaborate network of proteins that confer cellular protection by augmenting their expression in response to disturbances in oxidative stress. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcription factor that has a pivotal role in mediating this intracellular antioxidant response since it upregulates the expression of numerous antioxidant and phase II detoxification enzymes in response to increases in oxidative stress (31). Mice deficient for Nrf2 exhibit a marked reduction in the expression of these enzymes, consequently increasing their sensitivity to the toxic effects of various drugs (12) and chemical compounds (33). The inability of these mice to initiate a response that counteracts the adverse effects of oxidative stress illustrates the importance of Nrf2 in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis.

Under quiescent conditions, the Nrf2 signaling pathway is negatively regulated by Kelch-like ECH associating protein 1 (Keap1). Keap1 constitutively targets Nrf2 for ubiquitin conjugation and subsequent proteasome degradation in the cytoplasm by acting as a substrate adaptor for the Cul3-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (10, 19). Because of the negative regulatory system of Keap1, Nrf2 is rapidly turned over, with a half-life of less than 20 min (19). However, increases in oxidative stress promote the activation and stabilization of Nrf2. Nrf2 activation is thought to involve the modification of the sulfhydryl groups of specific cysteine residues found within the linker region of Keap1, which results in a conformational change that alters the binding capacity of Keap1 with Nrf2 (20, 44). In turn, this promotes the translocation of Nrf2 to the nucleus where it can interact and form heterodimers with small Maf proteins (16, 17), recruit transcriptional coactivators (39, 41) to help remodel chromatin structure, and bind to the antioxidant response element (ARE) found within the promoter region of target genes (31). The fact that Keap1 contains distinct cysteine residues (44) that can be targeted and modified by electrophiles, reactive oxygen species (ROS), or antioxidant response element-inducers suggests that the Keap1-Nrf2 interaction functions as a sensor of the redox state of the cell.

While it is well established that Nrf2 is important for antioxidant expression, emerging evidence also suggests that Nrf2 signaling protects the structure and function of skeletal muscle, in part, through the preservation of redox homeostasis. For instance, Safdar et al. (35) reported a significant decrease in nuclear Nrf2 expression in elderly humans leading a sedentary lifestyle, while recreationally active individuals exhibited improved Nrf2 function. Disruption of Nrf2 has also been shown to induce oxidative stress resulting in greater ubiquitination, lipid peroxidation, and proapoptotic signals in skeletal muscle of aged Nrf2 knockout (KO) mice (26). Further, aged Nrf2 KO mice also demonstrate impaired muscle regeneration following acute endurance exercise stress due to a decrease in Pax7 and MyoD expression (30). Interestingly, Nrf2 has also been implicated in regulating mitochondrial content (32) and function (15, 18) in some cell types. The work conducted by Piantadosi et al. (32) revealed that nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1) contains multiple AREs within its promoter that become occupied by Nrf2 upon induction by ROS. Exhaustive exercise has also been shown to be a particular stressor capable of inducing Nrf2 activation, nuclear accumulation, and ARE binding within cardiomyocytes (29). However, the role of Nrf2 in mediating changes in mitochondrial content and function in skeletal muscle remains to be elucidated. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to examine the role of Nrf2 within skeletal muscle, its impact on mitochondrial content, and its relationship to exercise performance in 3- and 12-mo-old mice. Furthermore, we also subjected both Nrf2 wild-type (WT) and KO animals to a 6-wk voluntary running wheel training protocol to determine if Nrf2 was required for exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. This relatively low-stress exercise training protocol effectively induces organelle biogenesis in mouse skeletal muscle (36).

METHODS

Animals.

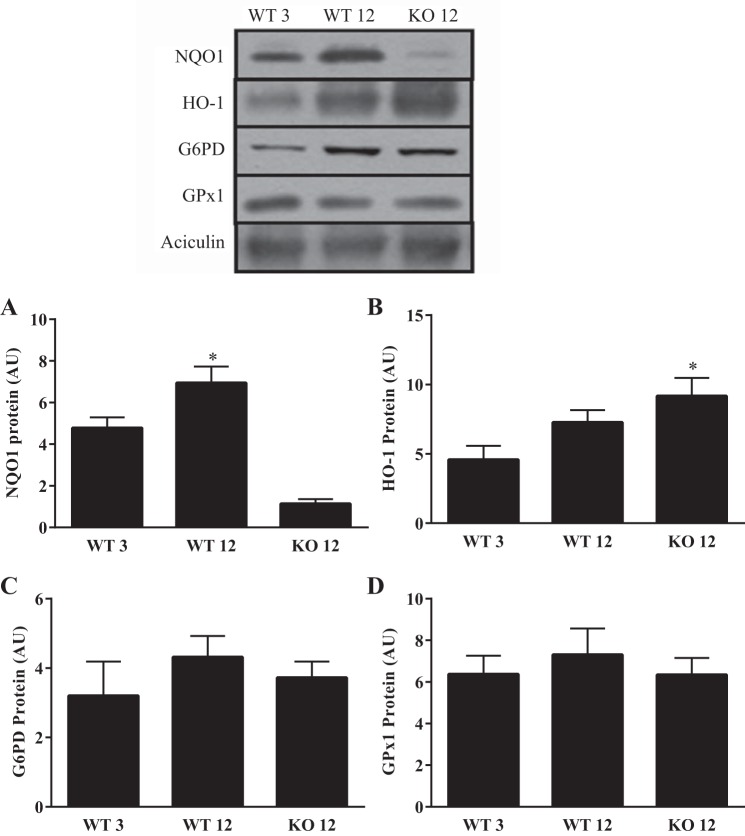

Nrf2 KO and heterozygous mice (maintained on a C57BL/6J background) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were bred in accordance with the guidelines of the York University Animal Care Committee. Progeny were genotyped by obtaining ear clippings, which were subsequently used for crude DNA extraction. DNA extracts were incubated with Jumpstart RED-Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), as well as forward and reverse primers specific to the WT or mutant nucleotide sequences, and amplified by polymerase chain reaction. The reaction products were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel and visualized with the use of ethidium bromide to distinguish between WT, KO, or heterozygous (HT) animals (Fig. 1A). Nrf2 WT and KO animals were used at 3 and 12 mo of age. The older middle-aged group was employed to see if any phenotypic or physiological differences observed between WT and KO animals was exacerbated with a moderate degree of aging. All procedures involving animals were approved and conducted in accordance with the regulations of the York University Animal Care Committee in compliance with the guidelines set forth by the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Fig. 1.

Genotyping, wheel running performance, and body and gastrocnemius weight in Nrf2 WT and KO mice. A: genotyping of animals used in the study. Box 1, pattern for KO mice; box 2, pattern for heterozygous (HT) mice; box 3, pattern for WT mice. Genotyping was performed as described in methods before all experiments were conducted. B: weekly average wheel running distance accumulated by 3-mo-old Nrf2 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice over a period of 6 wk (n = 9–10); UT, untrained; T, trained. C and D: body and gastrocnemius weight of Nrf2 WT and KO young mice following the 6 wk training period (n = 6–10), along with measures for the middle-aged mice. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05; two-way ANOVA produced a main effect of age.

Voluntary wheel running.

At 3 mo of age, Nrf2 WT and KO mice were age matched and assigned to a control or running group. The mice were housed individually, allowed access to food and water ad libitum, and kept on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Runners had access to a freely rotating wheel, while the revolutions were recorded by a magnetic counter. The number of revolutions was recorded every 24 h and converted into distance (kilometers) per day. The duration of the training protocol was ∼6-8 wk. Following the training protocol (48 h later), mice were subjected to an endurance exercise capacity test and in situ stimulation for further performance analysis.

Acute in situ muscle stimulation.

The stimulation protocol was performed as described previously (37). Briefly, the right gastrocnemius muscle was attached to a force transducer via the Achilles tendon and the sciatic nerve innervating the muscle was stimulated at 0.25 tetanic contractions per second (TPS), 0.5 TPS, and 1 TPS for 3 min each. These intensities were sufficient to induce moderate and more severe muscle fatigue, respectively. Twitch contractions were analyzed for contractile properties, and maximum tetanic force was measured, while subsequent contractions were expressed as a percentage of maximum. Following the in situ stimulation protocol, the stimulated muscle was excised, quickly frozen, and weighed.

Cytochrome-c oxidase activity.

Cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) enzyme activity was measured as previously described (42) by determining the maximal rate of oxidation of fully reduced cytochrome-c, evaluated as a change in absorbance at 550 nm by using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Synergy HT, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Immunoblotting.

Whole muscle protein extracts from the gastrocnemius muscle were separated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Following the transfer, the membranes were blocked for 1 h with a solution of 5% skim milk in 1X TBST (Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20: 25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20). Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with antibody directed against HO-1 (ab13248, Abcam), NQO1 (ab34173, Abcam), G6PD (8866, Cell Signaling), GPx1 (ab22604, Abcam), and Nrf2 (SC722, Santa Cruz). The Nrf2 band measured was detected between 95–100 kDa based on a critical analysis of the predicted molecular weight of the protein (22). After three 5 min washes with TBST, blots were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with the appropriate secondary antibody coupled with horseradish peroxidase. Antibody-bound protein was revealed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method. Quantification was performed with Image J Software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and values were normalized to the appropriate loading controls (either GAPDH, aciculin, or Ponceau staining, as appropriate).

Mitochondrial isolation.

The tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius, quadriceps, and triceps muscles from both sides of the animal were minced, homogenized, and subjected to differential centrifugation to isolate subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondrial fractions, as described previously (8). Mitochondria were suspended in resuspension buffer (100 mM KCl, 10 mM MOPS, and 0.2% BSA). Following the isolation procedure, SS and IMF were used to assess mitochondrial respiration and ROS production.

Mitochondrial respiration.

Fifty microliters of isolated mitochondrial samples were incubated with 250 μl of V̇o2 buffer (in mM: 250 sucrose, 50 KCl, 25 Tris, and 10 K2HPO4, pH 7.4) in a Clark oxygen electrode respiratory chamber (Strathkelvin Instruments, North Lanarkshire, UK) with continuous stirring at 30°C. Mitochondrial oxygen consumption was measured in the presence of exogenously added 10 mM glutamate to assess state 4 respiration followed by 0.44 mM ADP to elicit state 3 respiration. Finally, NADH was added during state 3 measurements to evaluate the integrity of the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Mitochondrial ROS production.

SS and IMF mitochondria (75 μg) were incubated with 50 μM dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) and V̇o2 buffer at 37°C for 30 min in a white polystyrene 96-well plate. The fluorescence emission (between 485 and 528 nm) is directly proportional to ROS production and was measured with a Synergy HT microplate reader. ROS production was assessed under both state 4 and state 3 respiration.

Nrf2 activation assay.

Nrf2 activation and ARE binding efficacy under both basal and acute exercise stress conditions were evaluated in WT and KO mice by using nuclear extracts obtained from the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle with a Trans AM Nrf2 kit (50296, Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). A 10-μg aliquot of nuclear protein was incubated with immobilized oligonucleotides containing the ARE consensus binding site (5′GTCACAGTACTCAGCAGAATCTG-3′). Active Nrf2 that bound to the oligo was detected with the Nrf2 primary antibody and subsequent HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Specific activity of Nrf2 in the nuclear extracts was determined with a plate reader at 450 nm, and absorbance was expressed as the direct activity of Nrf2.

Endurance exercise capacity test.

Nrf2 WT and KO mice were acclimated to the treadmill for 2 days prior to the test. On the exercise testing day, the mice ran on the treadmill with a fixed slope of 10%. Mice ran for 5 m/min for 5 min followed by 10 m/min for 10 min, 15 m/min for 15 min, and 20 m/min for 20 min. The speed was then increased by 2 m/min every 2 min until exhaustion was achieved. Exhaustion was defined as the inability of the animal to run on the treadmill for 10 s despite prodding.

Nuclear and cytosolic fractionation.

Immediately following the endurance exercise capacity test, the TA muscle was immediately removed and placed into ice-cold phosphate buffered saline with protease inhibitors. Nuclear and cytosolic fractionation was conducted with the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents kit (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with Graphpad 6.0 software. Values are reported as means ± SE. A Student's t-test was used to analyze the Nrf2 activation assay and comparisons between slopes during the initial 2-min of in situ stimulation. State 4 and state 3 respiration and ROS were analyzed by ANOVA. All other data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA unless otherwise indicated. Significance levels were set at P < 0.05 by a Bonferonni post hoc test.

RESULTS

Response of Nrf2 KO mice to voluntary exercise.

To evaluate the effect of Nrf2 on exercise-induced adaptations, both WT and KO mice were subjected to 6 wk of voluntary running wheel exercise training. Throughout the 6-wk period, the WT and KO mice exhibited no differences in running performance, as both genotypes averaged ∼11 km/day (Fig. 1B). Body mass and gastrocnemius weight were evaluated in the WT and KO mice at 3 and 12 mo of age, respectively, to determine the effect of training or age. There was no effect of training or genotype on body mass (Fig. 1C) or gastrocnemius mass (Fig. 1D). Although the WT and KO mice at 12 mo of age did not differ from each other in body mass, the older animals had an ∼38% greater body mass relative to their younger counterparts and they displayed a ∼19% reduction in gastrocnemius mass. These results indicate that the Nrf2 KO mice do not differ from their WT counterparts in their voluntary running performance or phenotypic traits at 3 and 12 mo of age.

Endurance performance of Nrf2 KO mice following 6 wk of wheel running.

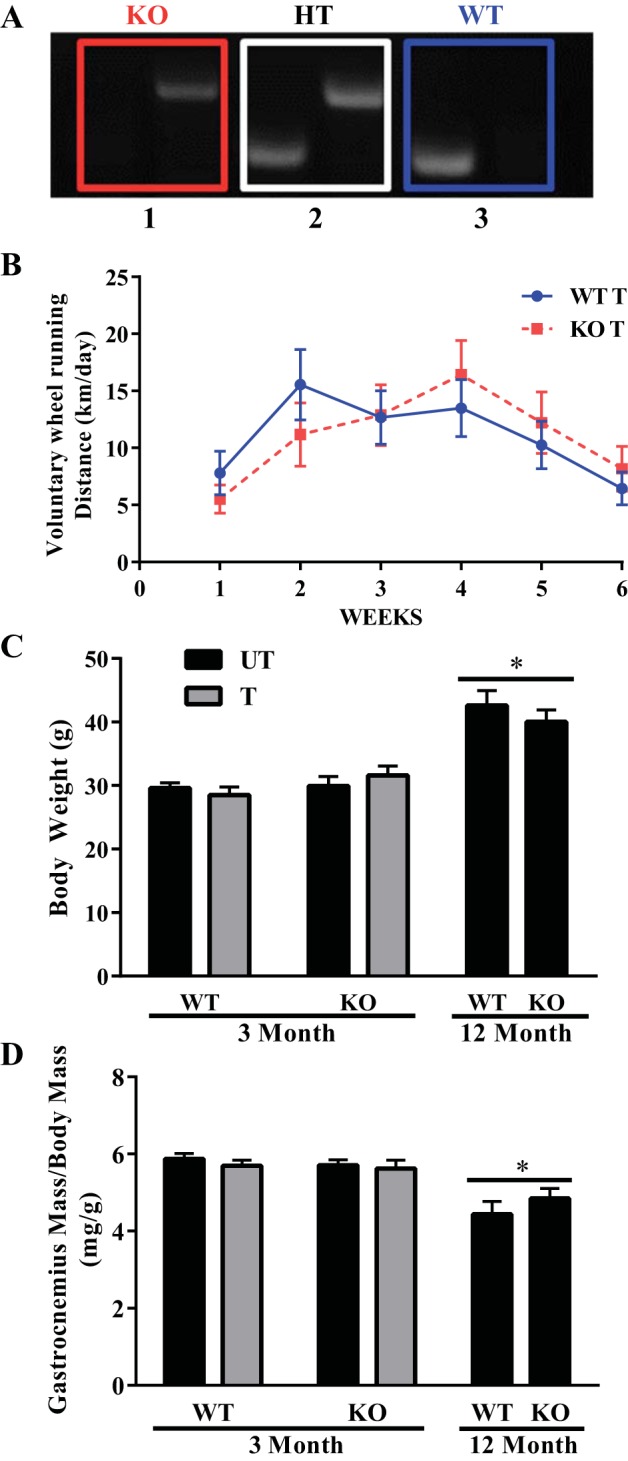

Following the 6 wk of voluntary wheel running, we assessed the exercise tolerance of WT and KO mice by subjecting them to an endurance exercise capacity test. Untrained (UT) Nrf2 KO mice exhibited a similar running distance and time to exhaustion to their WT counterparts (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, both genotypes adapted equally well to training, with 109 and 134% increases in running distance in the KO and WT mice, respectively. As expected, the WT and KO older animals displayed attenuated endurance capacities, characterized by 28 and 17% lower distances and times to exhaustion, relative to the young untrained mice. Lactate levels were elevated from 2 mM at rest to 7–11 mM following exercise. There were no effects of age, training status, or genotype on lactate levels (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Endurance exercise capacity test. Following the 6 wk of voluntary wheel running, the running performance of the untrained and trained young mice, as well as that of the middle-aged mice were compared by subjecting them to an exhaustive bout of exercise. A and B: running performance was measured by recording both the distance (n = 6–9) and time (n = 6–9) to exhaustion. *P < 0.05 T vs. UT; ¶P < 0.05 main effect of age, two-way ANOVA. C: lactate production was also measured before and after exercise. *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA produced a main effect of exercise.

In situ stimulation and force production.

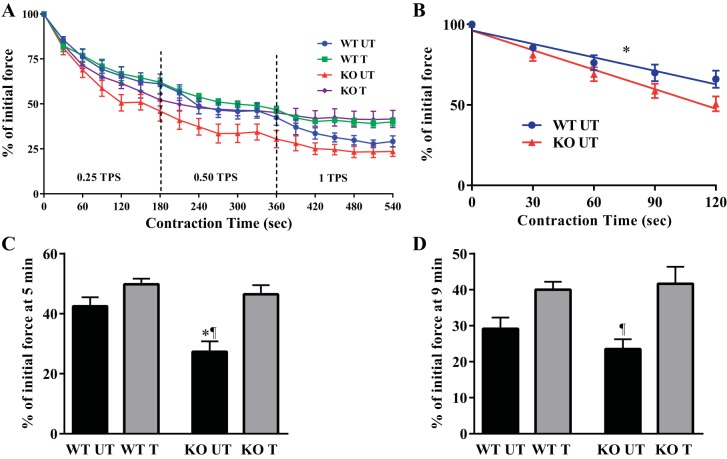

To further evaluate the role of Nrf2 in force generation and fatigability in isolated muscle, we stimulated the gastrocnemius-plantaris-soleus muscle group in situ in anesthetized mice at 0.25, 0.50, and 1 TPS (Fig. 3A). Maximum tetanic force, time to peak tension, and half relaxation were similar in all groups (Table 1). However, within the first 2 min of stimulation, the KO untrained animals demonstrated a 48% greater rate of fatigue (P < 0.05) relative to the WT untrained animals (Fig. 3B). Indeed, the untrained KO mice demonstrated significantly increased rates of fatigue as determined by lower force generation at both the 5 and 9 min time points (Fig. 3, C and D). Endurance training abolished this defect and normalized the fatigue in the KO animals to that found in WT untrained animals. Collectively, these results suggest that Nrf2 is important for the maintenance of fatigue resistance in skeletal muscle.

Fig. 3.

Muscle performance in response to acute in situ stimulation. A: the gastrocnemius muscle of WT UT, WT T, KO UT, and KO T mice was stimulated at 0.25, 0.50, and 1 tetanic contraction per second (TPS) with force production being used as an index of muscle fatigue (n = 8–10). B: graphical representation depicting the linear regression of the WT UT and KO UT fatigue rate within the first two min of stimulation. *P < 0.05 WT UT vs. KO UT, Student's t-test. C: force production at 5 min of stimulation. *P < 0.05 WT UT vs. KO UT; ¶P < 0.05 KO UT vs. KO T, ANOVA. D: force production at end of stimulation. ¶P < 0.05 KO UT vs. KO T, ANOVA. Data are means ± SE.

Table 1.

Contractile properties of Nrf2 WT and KO skeletal muscle

| Condition | GW | GW/BW | TW/GW | TET/GW | TPT | ½ RT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg | mg/g | mN/mg | mN/mg | ms | ms | |

| WT UT | 173.5 ± 5.45 | 5.87 ± 0.17 | 1.83 ± 0.35 | 6.72 ± 0.54 | 21.36 ± 1.16 | 35.36 ± 1.76 |

| WT T | 162.4 ± 8.53 | 5.69 ± 0.16 | 2.39 ± 0.27 | 6.56 ± 0.59 | 22.17 ± 2.01 | 34 ± 4.12 |

| KO UT | 169.40 ± 5.92 | 5.71 ± 0.14 | 2.01 ± 0.14 | 5.43 ± 0.57 | 18.67 ± 1.91 | 32.4 ± 2.29 |

| KO T | 176.89 ± 10.93 | 5.62 ± 22 | 2.25 ± 0.21 | 6.91 ± 0.67 | 21.0 ± 1.77 | 30.36 ± 0.36 |

Data are represented as means ± SE; n = 9–10. Anatomical characteristics and gastrocnemius contractile properties of young WT and Nrf-2 KO animals.

GW, gastrocnemius weight; BW, body weight; TW, maximum twitch force; TET, maximum tetanic force; TPT, time to peak twitch tension; ½ RT, half relaxation time; UT, untrained; T, trained.

Adaptability of Nrf2 KO mice following 6 wk of wheel running.

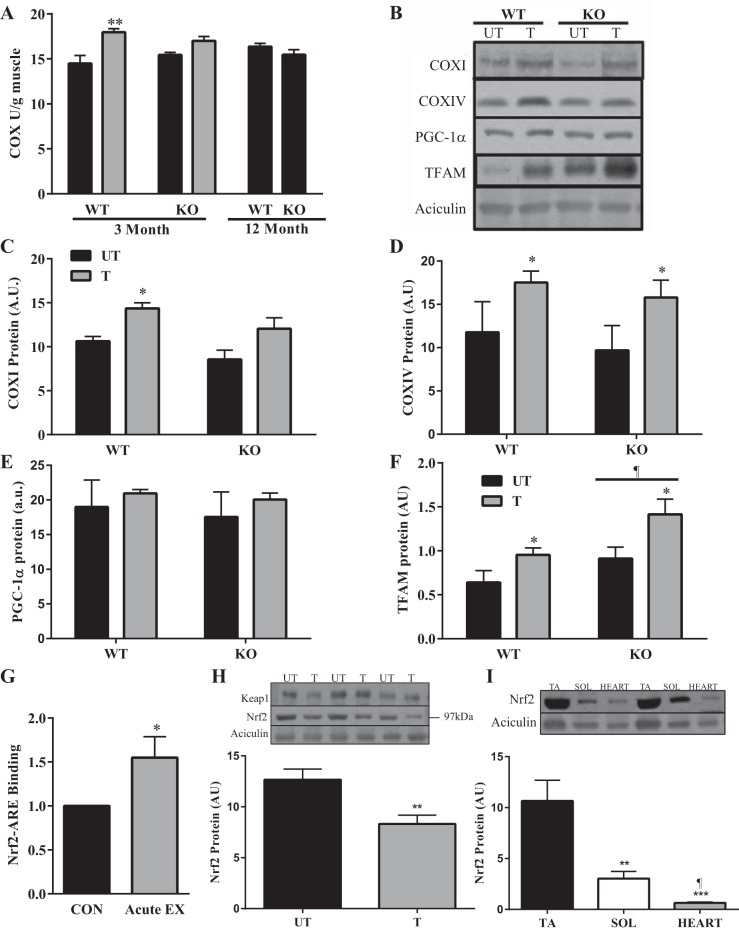

To investigate whether differences in muscle fatigability could be attributed to changes in mitochondrial content and to evaluate whether Nrf2 was required for mitochondrial adaptations to exercise, we measured COX activity, a well-established biochemical indicator of mitochondrial volume. There was no observed difference in COX activity between the WT and KO animals at either 3 or 12 mo of age (Fig. 4A). While training enhanced COX activity by 20% in the WT animals, this increase was only 10% in the KO mice, suggesting that Nrf2 could be required for complete exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptations. To verify this further, we used immunoblotting to measure alternative mitochondrial markers including COX subunits I and IV, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), and PGC-1α in whole muscle samples (Fig. 4, B–F). A significant effect of training was observed for COXI in WT, but not KO animals (Fig. 4, B and C). However, both COXIV (Fig. 4D) and TFAM (Fig. 4F) were significantly increased with training in muscle from both genotypes. Surprisingly, TFAM expression was significantly higher overall in KO animals. PGC-1α protein levels (Fig. 4E) were not altered as function of genotype, or training in this study. Thus Nrf2 is involved in exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in a protein-specific manner. This involvement would imply that Nrf2 could be activated during exercise. To verify this in response to an exhaustive bout of exercise, we utilized nuclear extracts from WT TA muscle at 3 mo of age in an ARE-oligonucleotide-based transactivation assay. Following an exhaustive bout of exercise, skeletal muscle Nrf2 activity was significantly increased (1.5-fold) compared with the sedentary WT mice (Fig. 4G). These results suggest that acute exercise is capable of increasing Nrf2-DNA binding and transcriptional activity in skeletal muscle. To examine the adaptability of Nrf2 to a 6-wk voluntary wheel running training protocol, we measured Nrf2 protein levels in UT and trained (T) WT mice. Surprisingly, we found a 30% reduction in Nrf2 protein levels following training (Fig. 4H). Interestingly, there were no changes observed in Keap1 protein levels. Steady-state Nrf2 protein levels were also investigated in the TA, soleus, and heart muscles to determine the relationship between Nrf2 and mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity in different muscle fiber types. Protein content was highest in the least oxidative muscle (TA), and exhibited a 75% reduction in the soleus, and a 90% reduction in the heart, the most oxidative striated muscle investigated (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4.

Adaptations to training in the Nrf2 WT and KO animals. A: COX activity (n = 6–7) of the gastrocnemius muscle in response to voluntary wheel running or age. **P < 0.01 T vs. UT, two-way ANOVA. B: Western blots of COXI, COXIV, PGC-1α, and TFAM from whole muscle samples in Nrf2 WT and KO mice following 6 wk of wheel running. C–F: graphical representation of COXI (n = 6), COXIV (n = 7–9), PGC-1α (n = 7–9), and TFAM (n = 7–9). *P < 0.05 vs. UT, ¶P < 0.05 main effect of genotype, two-way ANOVA. Data are means ± SE. G: ARE-based transactivation assay (n = 7) to determine if exercise can induce Nrf2 activation; bars represent fold change in acute exercise group relative to sedentary mice. *P < 0.05, Student's t-test. Data are means ± SE. H: Western blots of Nrf2 and Keap1 protein expression in WT UT and WT T mice with graphical representation of Nrf2 (n = 6); **P < 0.01, WT UT vs. T, Student's t-test. Data are means ± SE. I: Western blot and graphical representation of Nrf2 protein expression in tibialis anterior (TA), soleus (SOL), and heart (HEART) from WT mice (n = 4); **P < 0.01, SOL vs. TA; ***P < 0.001 HEART vs. TA; ¶P < 0.05 HEART vs. SOL, two-way ANOVA. Data are means ± SE.

Respiration and ROS production.

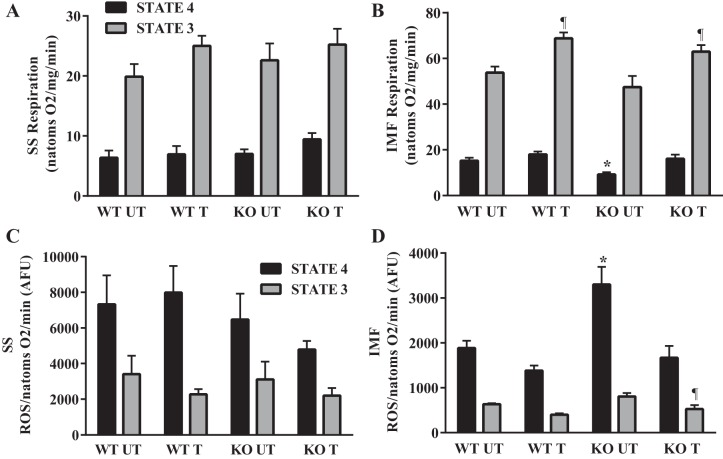

To determine if the absence of Nrf2 has an effect on respiration or ROS production, we isolated both the SS and IMF mitochondria. Lack of Nrf2 did not affect either state 4 or state 3 respiration rates in SS mitochondria (Fig. 5A). However, state 4 respiration in IMF mitochondria was reduced by 40% in the untrained KO animals relative to WT controls (Fig. 5B). Six weeks of voluntary wheel running completely rescued this effect and augmented state 3 respiration rates by 33% (P < 0.05). In addition, although no differences were observed in the SS mitochondria (Fig. 5C), ROS production in IMF mitochondria was particularly affected by the loss of Nrf2. Under state 4 conditions, we observed a 68% (P < 0.05) increase in ROS in the KO untrained animals compared with the WT animals (Fig. 5D). Training was sufficient to rescue this response in the KO animals. Taken together, these results indicate that the SS and IMF mitochondria respond differently to the loss of Nrf2. In particular, IMF mitochondria exhibit a greater dependence on Nrf2-driven gene expression for the maintenance of basal respiration rates.

Fig. 5.

Respiration and ROS production in isolated mitochondria from young Nrf2 WT and KO animals. A and B: oxygen consumption in isolated SS (n = 6–8) and IMF mitochondria (n = 10) during state 4 and state 3 respiration. *P < 0.05 KO UT vs. WT UT; ¶P < 0.05 T vs. UT, ANOVA. C and D: reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the SS and IMF mitochondria during state 4 and state 3 respiration. *P < 0.05 KO UT vs. WT UT; ¶P < 0.05 KO T vs. KO UT. Data are means ± SE.

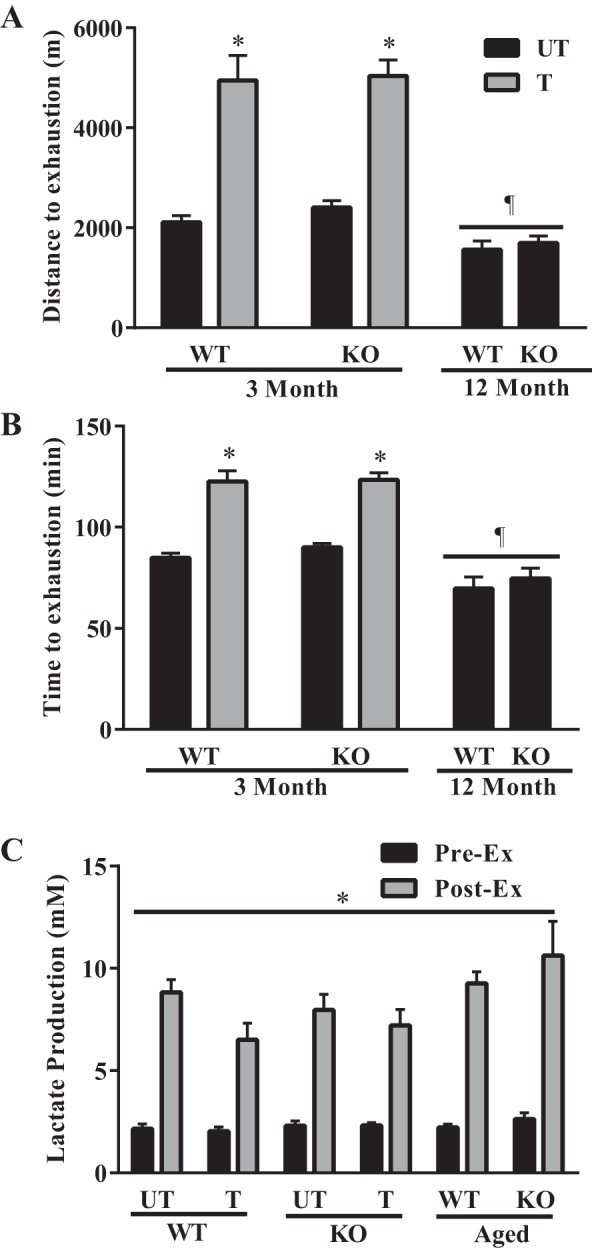

Compositional differences in isolated IMF mitochondria following training.

To determine if compositional differences account for some of the functional discrepancies between the WT and KO IMF mitochondria, we measured different electron transport chain subunits as well as TFAM. Interestingly, we did not observe any difference in either COXI or COXIV protein expression (Fig. 6A). However, we did observe a main effect of training regarding UQCRC2 (Fig. 6B) and TFAM expression (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Compositional differences in isolated IMF mitochondria from young trained and untrained mice. Western blots depicting COXI (n = 6), COXIV (n = 6), TFAM (n = 6), and UQCRC2 (n = 6) protein expression in isolated IMF mitochondria. A and B: graphical representation of UQCRC2 and TFAM. *P < 0.05 main effect of training, 2-way ANOVA. Data are means ± SE.

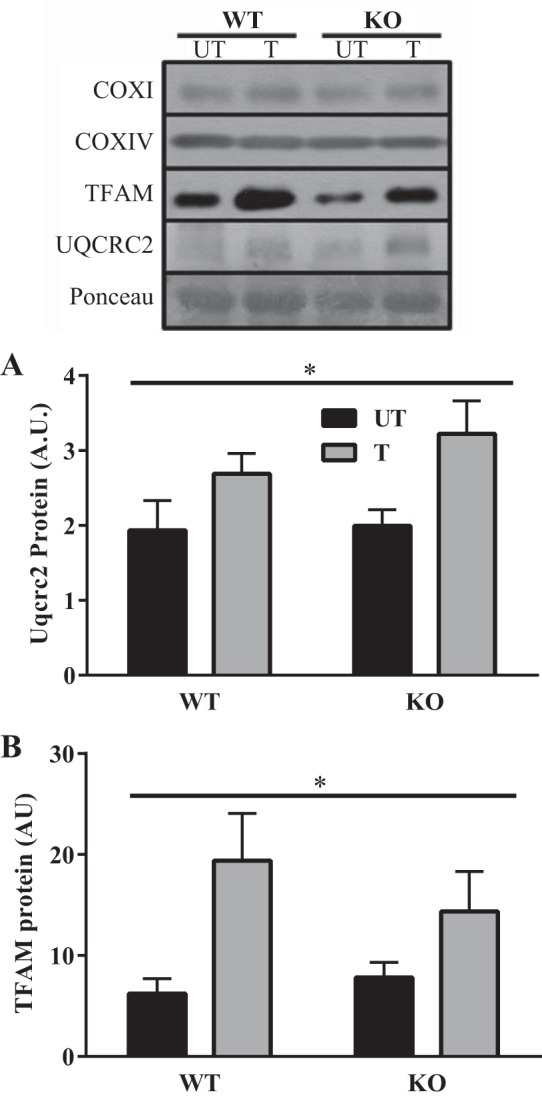

Antioxidant enzyme expression.

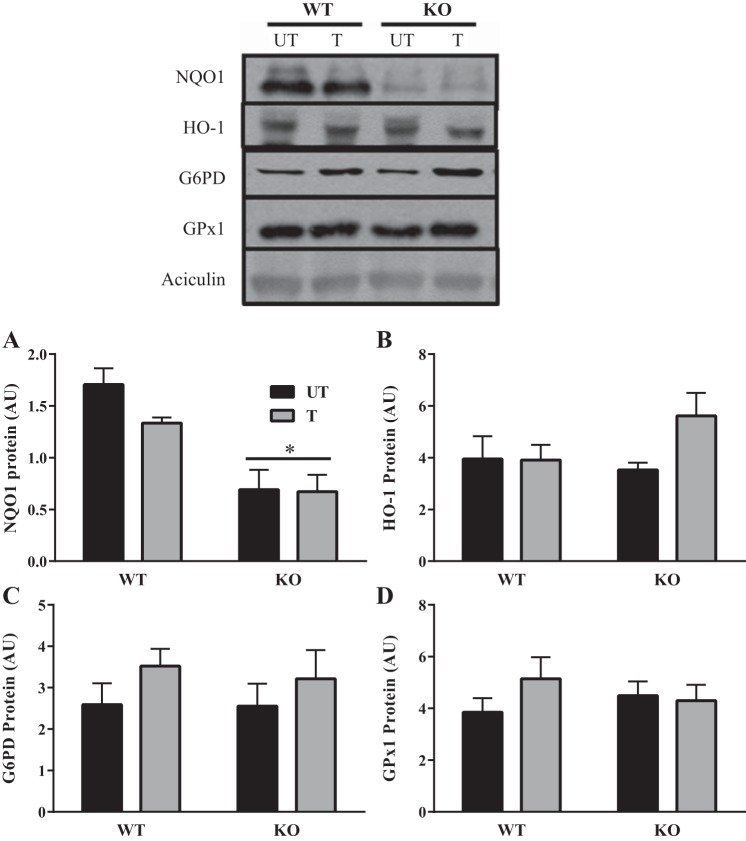

To assess whether Nrf2 deficiency influenced the levels of key antioxidant enzymes, we examined NQO1, HO-1, G6PD, and GPx1 protein levels in muscle since these are well-established downstream targets of Nrf2 identified in other tissues. Abrogation of Nrf2 resulted in significant reductions in NQO1 protein expression (Fig. 7A). Training could not rescue this effect in the KO animals, indicating that NQO1 expression is heavily reliant on the presence of Nrf2 under both basal and stressful conditions. Curiously, despite the reductions observed in NQO1, we did not find any differences in the level of other Nrf2 targets in muscle between WT and KO animals (Fig. 7, B–D).

Fig. 7.

Antioxidant enzyme expression in skeletal muscle of young trained and untrained mice. Western blots depicting NQO1 (n = 6), HO-1 (n = 7), G6PD (n = 9), and GPx1 (n = 9) protein expression in WT and KO mice in both untrained and trained conditions. A–D: graphical representation of NQO1, HO-1, G6PD and GPx1. *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA produced a main effect of genotype. Data are means ± SE.

Differences in antioxidant enzyme expression with age.

To investigate whether the lack of effect of Nrf2 KO on antioxidant enzyme expression was influenced by age, we compared young and older animals. Interestingly, we observed a 45% increase (P < 0.05) in NQO1 expression in the older WT animals compared with the young (Fig. 8A). However, significant reductions in NQO1 continued to be observed in the older KO animals. Conversely, HO-1 expression was increased 62% (P < 0.05) in the older KO animals relative to the WT young mice (Fig. 8B). Age and genotype did not influence the expression of either G6PD or GPx1 (Figs. 8, C and D).

Fig. 8.

Antioxidant enzyme expression in young and middle-aged WT and KO mice. Western blots depicting NQO1 (n = 7), HO-1 (n = 5–7), G6PD (n = 5–7), and GPx1 (6–7) protein expression in young (Y) and middle-aged (A) WT and KO mice. A–D: graphical representation of NQO1, HO-1, G6PD, and GPx1. *P < 0.05 vs. WT Y, ANOVA; ¶P < 0.05 KO A vs. WT Y/A, ANOVA. Data are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

Exercise is a potent stimulus and metabolic stressor that is capable of provoking adaptations in skeletal muscle which allow it to meet repeated increases in metabolic demand. One of the most dramatic phenotypic adaptations that occurs in response to exercise training is the increase in mitochondrial content and ultrastructure, a process commonly referred to as mitochondrial biogenesis. Although mitochondrial regulation depends on the interplay between transcription factors such as NRF-1/2, PPARα, ERRα, and Sp1, in addition to members of the PGC-1 family of regulated coactivators (PGC-1α and PGC-1β) (38), the role of Nrf2 in regulating mitochondrial content and function within skeletal muscle has not been established. Through a wealth of experimental evidence, the prevailing view of Nrf2 is that it sits at the crux of cellular defense mechanisms that are important for adaptive and survival responses under conditions of stress (7, 11, 31, 43). However, it is becoming apparent that Nrf2 has a much broader function since it has emerging roles in metabolism, bioenergetics, and skeletal muscle integrity, as well as mitochondrial content and function (15, 18, 26, 27, 30, 32, 35, 40, 43). For instance, genetic deletion of Nrf2 in mouse liver leads to a reduction in mitochondrial content (45). In mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), loss of Nrf2 was shown to impair mitochondrial respiration, resulting in a greater reliance on glycolysis for ATP generation (15). It has also been demonstrated in cultured cells that Nrf2 knockout affects the efficiency of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (25) and increases the susceptibility of mitochondria to the permeability transition (40). Our data also suggest that Nrf2 is required for basal mitochondrial function since the ablation of Nrf2 impaired state 4 respiration rates of IMF mitochondria in muscle from KO animals by 40%, and ROS emission in the IMF mitochondria was significantly elevated in the null animals during state 4 conditions. These results are in accordance with those obtained in MEFs (15) and cortical neurons (21). However, abrogation of Nrf2 did not result in an increase in ROS production within the myocardium (29), suggesting that there may be tissue-specific differences in the dependence of mitochondrial function of Nrf2. Although we did not observe any compositional differences in the IMF mitochondria of WT and KO animals by using a limited number of organelle markers, it is possible that changes in mitochondrial respiration and ROS production could be due to differences in uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3) expression. Anedda et al. (5) identified an ARE within the UCP3 promoter that bound Nrf2 after exposure to H2O2. Furthermore, siRNA against Nrf2 prevented the H2O2-induced UCP3 expression, which culminated in an increase in oxidative stress and cell death. Indeed, we have previously shown that UCP3 content is 1.3-fold greater in IMF compared with SS mitochondria, which may partially explain the dissimilar effects of Nrf2 abrogation on mitochondrial function between the two subfractions (23).

Given the impact of Nrf2 on mitochondrial function, we sought to investigate the exercise tolerance of the KO animals by subjecting them to an exhaustive run at both 3 and 12 mo of age. We used the older animals at 12 mo because we initially observed no strong phenotypic differences at the younger age, and we felt that differences might become more apparent with age. Interestingly, the untrained KO mice displayed comparable distances and times to exhaustion, as well as similar lactate production, relative to their WT counterparts. While the reductions in endurance capacity evident in the 12-mo-old animals are consistent with the notion that older animals typically display lower endurance and greater rates of fatigue (24), the absence of Nrf2 did not hinder running performance even at an older age. In addition, the 12-mo-old animals displayed a modestly reduced muscle mass/body weight ratio; however, absolute muscle mass values were similar (data not shown). The age-induced reduction in muscle mass/body weight ratio was due to an age-induced increase in body weight, likely due to fat accumulation.

The lack of any difference in endurance capacity between the young untrained WT and KO animals is likely because active (state 3) respiration was comparable between the two genotypes. Given that mitochondrial respiration during aerobic contractile activity likely reflects rates similar to state 3 respiration in vitro, this suggests that the KO mice would not have experienced a functional deficit in ATP provision sufficient enough to inhibit their running capacity. Interestingly, this did not translate into identical muscle performance when we investigated the contractile properties of skeletal muscle of Nrf2 WT and KO mice in situ. Our findings demonstrated that while there was no difference in the maximal strength of the muscle, the endurance capacity of Nrf2 KO skeletal muscle during a short-term isolated muscle test was reduced. This difference between whole body and isolated muscle performance characteristics may be due to behavioral differences between WT and the whole body KO mice. Muramatsu et al. (28) have argued that dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission is enhanced in the KO animals, which increases their ability to resist stress. Certainly a limitation of our study is that we cannot completely eliminate the knockout of Nrf2 in other tissues as a potential influence on the running performance results of our study. A conditional knockout of Nrf2 within skeletal muscle alone would help us resolve this issue. However, the use of the in situ muscle preparation was advantageous in eliminating behavioral and whole body exercise effects, ultimately allowing us to identify the inherent differences in muscle contractile activity brought about by the lack of Nrf2, very similar to the interpretation that might be afforded by the use of a muscle-specific Nrf2 knockout animal. The greater rate of fatigue observed in the untrained KO animals may be partially attributed to high levels of ROS exposure. Indeed, we did observe a profound increase in mitochondrially derived ROS in the KO animals. Additionally, Kovac et al. (21) found that NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) is dramatically upregulated under conditions of Nrf2 deficiency. Recently it has been argued that the NOX enzymes are the major ROS generating source in contracting skeletal muscle (36). We speculate that an increase in ROS generation, partly as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction, may have promoted alterations in myofilament structure and function (6, 9, 14), diminished myofilament calcium sensitivity (3, 4), or influenced cross-bridge kinetics (4), leading to a greater rate of fatigue.

While evidence pertaining to the importance of Nrf2 for mitochondrial function is beginning to accumulate, no research has been devoted to understanding this relationship in muscle during stressful conditions. Research conducted by Piantadosi et al. (32) revealed that in response to increases in ROS, Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and occupies several AREs within the NRF-1 promoter. These findings, along with our observation that exercise can activate Nrf2 in skeletal muscle, suggest that Nrf2 may participate in the initial signaling events that culminate in the expansion of the mitochondrial reticulum with exercise training. The acute exercise-induced activation of Nrf2 is likely mediated by an increase in ROS production, since previous reports have shown that ROS can be a primary trigger promoting the dissociation of Nrf2 from Keap1, resulting in an increase in nuclear translocation and transcription of putative targets (19, 20, 34, 44).

To explicitly explore the relationship between Nrf2 and mitochondrial content, we subjected WT and KO animals to 6 wk of voluntary wheel running. Basally, we did not observe any difference in COX activity between the two genotypes at either 3 or 12 mo of age. However, significant training-induced increases in COX activity and COXIV subunit were only observed in the WT animals, suggesting that the initial nuclear translocation and signaling evoked by Nrf2 may be essential for exercise-induced increases in the activity of this terminal enzyme of the electron transport chain. However, Nrf2 did not appear to be required for the training-induced increases in COXIV, TFAM, or UQCRC2. Thus Nrf2 appears to be needed for the exercise-induced increases in only a subset of mitochondrial proteins, and the fact that Nrf2 expression declines with training is consistent with a waning importance for the protein beyond the initial acute exercise stress. Interestingly, despite the blunted change in COX activity in Nrf2 KO animals, training augmented the respiratory deficit that was evident in these animals, ultimately restoring respiration to WT levels. Again, this suggests that Nrf2 is required for the normal, stoichiometric protein adaptations in response to training, but that it is not required for the associated improvements in organelle function. Similar results have been reported by our laboratory using PGC-1α KO animals, whereby training elicited improvements in respiration back to normal levels despite the absence of PGC-1α (2). Therefore, chronic exercise training likely stimulates alternative regulatory proteins that are capable of augmenting respiration to compensate for the blunted increase in mitochondrial content observed with the absence of Nrf2.

One of our most striking findings was the marked reduction in NQO1 expression in the Nrf2 null animals, a result suggesting that the primary regulation of NQO1 is Nrf2 dependent. NQO1 is an oxidoreductase which is typically located within the cytoplasm. These drastic reductions in NQO1 could predispose the KO animals to metabolic abnormalities, since NQO1-deficient mice exhibit higher levels of hepatic triglycerides and are insulin resistant (13). Interestingly, its low expression in Nrf2 KO animals was not rescued by endurance training, suggesting that improvements in metabolic conditions associated with NQO1 deficiency would likely benefit more from pharmacological interventions. In addition, low NQO1 expression could potentially have ramifications for the stability of PGC-1α, since NQO1 appears to be critical for the protection and stabilization of both basal and physiologically-induced PGC-1α protein (1). However, we did not observe any differences in basal levels of PGC-1α between genotypes, suggesting that Nrf2 is not involved, either directly or indirectly via NQO1, in modifying PGC-1α protein levels in this tissue.

In summary, our results suggest that Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activity is increased by acute exercise and that the presence of Nrf2 is required for normal exercise-induced adaptations of mitochondrial proteins. However, chronic exercise 1) led to a reduction of Nrf2 protein levels in WT animals and 2) was capable of rescuing defects in mitochondrial function brought about by the absence of Nrf2. We suggest that this effect of exercise is due to a compensatory upregulation of alternative regulatory proteins which impact the expression of functional mitochondrial components in the absence of Nrf2, highlighting the ability of exercise training to activate a broad array of healthy physiological adaptations in muscle which extend far beyond a single signaling pathway.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (to D. Hood). D. Hood holds a Canada Research Chair in Cell Physiology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.J.C., L.D.T., and A.T.E. performed experiments; M.J.C. and A.T.E. analyzed data; M.J.C., A.T.E., and D.A.H. interpreted results of experiments; M.J.C. and A.T.E. prepared figures; M.J.C. and D.A.H. drafted manuscript; M.J.C. and D.A.H. edited and revised manuscript; M.J.C., L.D.T., A.T.E., and D.A.H. approved final version of manuscript; D.A.H. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamovich Y, Shlomai A, Tsvetkov P, Umansky KB, Reuven N, Estall JL, Spiegelman BM, Shaul Y. The protein level of PGC-1α, a key metabolic regulator, is controlled by NADH-NQO1. Mol Cell Biol 33: 2603–2613, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhihetty PJ, Uguccioni G, Leick L, Hidalgo J, Pilegaard H, Hood DA. The role of PGC-1α on mitochondrial function and apoptotic susceptibility in muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C217–C225, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol 509: 565–575, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Westerblad H. Contractile response of skeletal muscle to low peroxide concentrations: myofibrillar calcium sensitivity as a likely target for redox-modulation. FASEB J 15: 309–311, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anedda A, López-Bernardo E, Acosta-Iborra B, Saadeh Suleiman M, Landázuri MO, Cadenas S. The transcription factor Nrf2 promotes survival by enhancing the expression of uncoupling protein 3 under conditions of oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 61: 395–407, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callahan LA, Nethery D, Stofan D, Dimarco A, Supinski G. Free radical-induced contractile protein dysfunction in endotoxin-induced sepsis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 24: 210–217, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan K, Kan YW. Nrf2 is essential for protection against acute pulmonary injury in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 12731–12736, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cogswell AM, Stevens RJ, Hood DA. Properties of skeletal muscle mitochondria from subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar isolated regions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C383–C389, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowder M, Cooke R. The effect of myosin sulphydryl modification on the mechanics of fibre contraction. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 5: 131–146, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullinan S, Gordan J, Jin J, Harper J, Diehl J. The Keap1-BTB protein is an adaptor that bridges Nrf2 to a Cul3-based E3 ligase: oxidative stress sensing by a Cul3-Keap1 Ligase. Mol Cell Biol 24: 8477–8486, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7198–7209, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enomoto A, Itoh K, Nagayoshi E, Haruta J, Kimura T, Connor TO. High sensitivity of Nrf2 knockout mice to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity associated with decreased expression of ARE- regulated drug metabolizing enzymes and antioxidant genes. Toxicol Sci 177: 169–177, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaikwad A, Long D, Stringer J, Jaiswal A. In vivo role of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in the regulation of intracellular redox state and accumulation of abdominal adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 276: 22559–64, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heusch P, Canton M, Aker S, van de Sand A, Konietzka I, Rassaf T, Menazza S, Brodde O, Di Lisa F, Heusch G, Schulz R. The contribution of reactive oxygen species and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase to myofilament oxidation and progression of heart failure in rabbits. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1408–16, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmström KM, Baird L, Zhang Y, Hargreaves I, Chalasani A, Land JM, Stanyer L, Yamamoto M, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY. Nrf2 impacts cellular bioenergetics by controlling substrate availability for mitochondrial respiration. Biol Open 2: 761–70, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, Yamamoto M, Nabeshima Y. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322: 313–322, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katsuoka F, Motohashi H, Ishii T, Engel JD, Yamamoto M, Aburatani H. Genetic evidence that small Maf proteins are essential for the activation of antioxidant response element-dependent genes. Mol Cell Biol 25: 8044–8051, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim TH, Hur E, Kang SJ, Kim JA, Thapa D, Lee YM, Ku SK, Jung Y, Kwak MK. NRF2 blockade suppresses colon tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1α. Cancer Res 71: 2260–75, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi A, Kang M, Okawa H, Zenke Y, Chiba T, Igarashi K, Ohtsuji M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7130–7139, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 regulation of cellular defense mechanisms against electrophiles and reactive oxygen species. Adv Enzyme Regul 46: 113–140, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovac S, Angelova PR, Holmström KM, Zhang Y, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY. Nrf2 regulates ROS production by mitochondria and NADPH oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850: 794–801, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau A, Tian W, Whitman SA, Zhang DD. The predicted molecular weight of Nrf2: it is what it is not. Antioxid Redox Signal 18: 91–93, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ljubicic V, Adhihetty PJ, Hood DA. Role of UCP3 in state 4 respiration during contractile activity-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. J Appl Physiol 97: 976–83, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ljubicic V, Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, Huang JH, Saleem A, Uguccioni G, Hood DA. Molecular basis for an attenuated mitochondrial adaptive plasticity in aged skeletal muscle. Aging 1: 818–30, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludtmann MHR, Angelova PR, Zhang Y, Abramov AY, Dinkova-Kostova AT. Nrf2 affects the efficiency of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Biochem J 457: 415–24, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller CJ, Gounder SS, Kannan S, Goutam K, Muthusamy VR, Firpo MA, Symons JD, Paine R, Hoidal JR, Rajasekaran NS. Disruption of Nrf2/ARE signaling impairs antioxidant mechanisms and promotes cell degradation pathways in aged skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822: 1038–50, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitsuishi Y, Taguchi K, Kawatani Y, Shibata T, Nukiwa T, Aburatani H, Yamamoto M, Motohashi H. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell 22: 66–79, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muramatsu H, Katsuoka F, Toide K, Shimizu Y, Furusako S, Yamamoto M. Nrf2 deficiency leads to behavioral, neurochemical and transcriptional changes in mice. Genes Cells 18: 899–908, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthusamy VR, Kannan S, Sadhaasivam K, Gounder SS, Davidson CJ, Boeheme C, Hoidal JR, Wang L, Rajasekaran NS. Acute exercise stress activates Nrf2/ARE signaling and promotes antioxidant mechanisms in the myocardium. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 366–76, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narasimhan M, Hong J, Atieno N, Muthusamy VR, Davidson CJ, Abu-Rmaileh N, Richardson RS, Gomes AV, Hoidal JR, Rajasekaran NS. Nrf2 deficiency promotes apoptosis and impairs PAX7/MyoD expression in aging skeletal muscle cells. Free Radic Biol Med 71: 402–14, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Nioi P, Yang CS, Pickett CB. Nrf2 controls constitutive and inducible expression of ARE-driven genes through a dynamic pathway involving nucleocytoplasmic shuttling by Keap1. J Biol Chem 280: 32485–32492, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piantadosi CA, Carraway MS, Babiker A, Suliman HB. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ Res 103: 1232–1240, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 114: 1248–1259, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rushmore TH, Morton MR, Pickett CB. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J Biol Chem 266: 11632–11639, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safdar A, DeBeer J, Tarnopolsky MA. Dysfunctional Nrf2-Keap1 redox signaling in skeletal muscle of the sedentary old. Free Radic Biol Med 49: 1487–93, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakellariou G, Jackson MJ, Vasilaki A. Redefining the major contributors to superoxide production in contracting skeletal muscle. The role of NAD(P)H oxidases. Free Radic Res 48: 12–29, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saleem A, Adhihetty PJ, Hood DA. Role of p53 in mitochondrial biogenesis and apoptosis in skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics 3: 58–66, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional paradigms in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol Rev 88: 611–638, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen G, Hebbar V, Nair S, Xu C, Li W, Lin W, Keum YS, Han J, Gallo MA, Kong AN. Regulation of Nrf2 transactivation domain activity. The differential effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades and synergistic stimulatory effect of Raf and CREB-binding protein. J Biol Chem 279: 23052–23060, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strom J, Xu B, Tian X, Chen QM. Nrf2 protects mitochondrial decay by oxidative stress. FASEB J 30: 66–80, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Z, Chin YE, Zhang DD. Acetylation of Nrf2 by p300/CBP augments promoter-specific DNA binding of Nrf2 during the antioxidant response. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2658–2672, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vainshtein A, Kazak L, Hood DA. Effects of endurance training on apoptotic susceptibility in striated muscle. J Appl Physiol 110: 1638–1645, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu KC, Cui JY, Klaassen CD. Beneficial role of Nrf2 in regulating NADPH generation and consumption. Toxicol Sci 123: 590–600, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang DD, Hannink M. Distinct cysteine residues in Keap1 are required for Keap1-dependent ubiquitination of Nrf2 and for stabilization of Nrf2 by chemopreventive agents and oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol 23: 8137–8151, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang YKJ, Wu KC, Klaassen CD. Genetic activation of Nrf2 protects against fasting-induced oxidative stress in livers of mice. PLoS One 8: e59122, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]