Abstract

Context

In the Women's Health Initiative estrogen plus progestin trial, after mean (SD) intervention of 5.6 (1.3) years (range 3.7 to 8.6 years) and mean follow-up of 7.9 (1.4) years, breast cancer incidence was increased by combined hormone therapy. However, breast cancer mortality results have not been previously reported.

Objective

To determine estrogen plus progestin effects on cumulative breast cancer incidence and mortality after a total mean follow-up of 11.0 (2.7) years thru August 14, 2009.

Design, Setting, and Participants

16,608 postmenopausal women, aged 50-79 years with no prior hysterectomy, were randomly assigned to combined conjugated equine estrogens (0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/d) or placebo. After the original trial completion date (March 31, 2005) re-consent was required for continued follow-up for breast cancer incidence and was obtained in 83%.

Main outcome measures

Invasive breast cancer incidence and breast cancer mortality.

Results

In intent-to-treat analyses including all randomized participants, censoring those on March 31, 2005 not-consenting for additional follow-up, estrogen plus progestin increased invasive breast cancers compared with placebo (385 [0.42%/yr] vs 293 [0.34%/yr] cases; hazard ratio [HR] 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07-1.46; P=.004). The breast cancers in the estrogen plus progestin group were similar in histology and grade but were more likely to be node positive (81 [23.7%] vs 43 [16.2%], respectively; P=0.03). Deaths directly attributed to breast cancer were greater in the estrogen plus progestin group (25 [0.03%/yr] vs 12 [0.01%/yr] deaths; HR, 1.96; 95% CI 1.00-4.04, P=.049) as were deaths from all causes occurring after a breast cancer diagnosis (51 [0.05%/yr] vs 31 [0.03%/yr] deaths; HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.01-2.48; P=.045).

Conclusions

Estrogen plus progestin increases breast cancer incidence with cancers more commonly node positive. Breast cancer mortality also appears to be increased with combined estrogen plus progestin use.

Introduction

Intervention in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) randomized trial evaluating estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women was stopped after a mean (SD) of 5.6 (1.3) years when health risks exceeded benefits for combined hormone therapy. 1 Combined hormone therapy increased invasive breast cancers 1, 2 and delayed breast cancer diagnoses resulting in more advanced stage. 2, 3 Recently, when examined after 7.9 years (1.4) mean (SD) follow-up, the breast cancer risk associated with combined hormone therapy declined soon after discontinuation of hormones. 4 Nonetheless, questions of clinical relevance remain, including the cumulative, long term effect of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer incidence and, whether breast cancer mortality is increased by combined hormone therapy use.

Most 5, 6,7 but not all, 8, 9 observational studies have suggested that breast cancers associated with combined menopausal hormone therapy have favorable characteristics, 5, 6, 7 less advanced stage 5,10 and less mortality risk. 7, 10, 11 As the issue of estrogen plus progestin influence on breast cancer mortality has not been addressed in a randomized trial setting, we provide updated information on breast cancer incidence and, for the first time, information on breast cancer mortality related to combined hormone therapy use in the WHI trial.

Methods

The WHI estrogen plus progestin trial has been previously described 1, 12, 13 and employed a study design approved by all Institutional Review Boards. 12, 14 Briefly, women were eligible if they were age 50-79 years, postmenopausal, and provided written informed consent. Excluded were women with prior hysterectomy, prior breast cancer or those with conditions precluding three year survival. Women using postmenopausal hormones required a 3-month wash-out period. Baseline mammograms and clinical breast exams not suggestive of cancer were required. Information on demographics, medical history, life-style, and breast cancer risk factors were collected with standardized self-report instruments. Medication use was assessed by interview-administered questionnaire. Time from menopause was defined as the interval from the onset of menopause to first hormone therapy or placebo use. 15 Adherence to study medication was assessed by dispensing history and serial pill counts by weighing returned pills.

Participants were randomized to conjugated equine estrogens (0.625 mg) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg) daily in a single tablet (Prempro;Wyeth Ayerst, Collegeville, PA) or an identical-appearing placebo. Randomization by permuted block algorithm, stratified by clinical center and age group, 14 was determined at the WHI Clinical Coordinating Center and implemented at local clinical centers using a bar-code dispensing procedure for staff and participant blinding. Participants were contacted at 6-month intervals to collect clinical outcome information and there were annual clinic visits. Yearly mammography and clinical breast exams were required during the intervention phase and study drugs were withheld until completion and clearance of abnormal findings. After the active intervention ended, annual mammogram and breast exam were encouraged and information on their frequency was collected annually.

The total study population included 16,608 women with initial randomization on November 15, 1993. The study intervention phase ended on July 7, 2002 after net harm for combined hormone therapy use was identified 1 and participants were instructed to stop study medication. In the postintervention phase beginning on July 8, 2002, clinical visits and follow-up continued per protocol thru March 31, 2005 the original trial completion date. In the study extension phase, subsequent follow-up from April 1, 2005 thru August 14, 2009 for additional breast cancer incidence results required re-consent (obtained from 83% of 15,408 surviving participants, n=12,788).

Breast cancers were verified by centrally-trained, locally-based physician adjudicators after medical record and pathology report review. 16 Final adjudication and coding of histology, hormone receptor status (positive or negative) and HER-2 status (over-expressing or not), based on pathology report review, was performed at the WHI Clinical Coordinating Center using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Coding System. 17 Attribution of cause of death was based on medical record review by the physician adjudicators, blinded to randomization allocation at the local clinical centers with final adjudication centrally. 16 The National Death Index (NDI) was run on all clinical trial participants at 2 to 3 year intervals.

Prior reports on invasive breast cancer initially included 349 cases identified during the intervention phase with mean (SD) follow-up 5.6 (1.3) years (median 5.6 years, range 4.6 to 8.6 years) 2 and 488 cases identified thru the original trial completion date with (mean (SD) follow-up of 7.9 (1.4) years. 4 The current report, based on a pre-planned analysis, includes 678 cases identified thru August 14, 2009 with a mean (SD) follow-up of 11.0 (2.7) years and includes breast cancer mortality information for the first time.

Statistical Analysis

For this trial, a target sample size of 15,125 participants was calculated primarily on coronary heart disease considerations. As a result, power to detect a 15% increase in breast cancer was 55% after 9 years and 87% after 5 more years of follow-up. 12

Comparisons of breast cancer characteristics were based on Fisher Exact and T tests. Age at menopause was defined as preciously described, 15 largely by age at last menstrual bleeding, bilateral oophorectomy date, or date menopausal hormone therapy was initiated.

Results for invasive breast cancer incidence and deaths from breast cancer were assessed with time-to-event methods based on the intention-to-treat principle. Analyses included all 16,608 randomized participants. Annualized percentages were calculated by dividing the total number of events by total follow-up time (years). Hazard ratios were estimated from Cox regression models stratified by baseline age (5 year age groups) and randomization status in the WHI dietary modification trial. No distinction was made between the intervention phase and the post-intervention phase. In both phases, the breast cancer risk for estrogen plus progestin use was greater than one and approximately equal. The summary (Cox model) hazard ratios represent an average over the entire study period. In addition, the null hypothesis tests for breast cancer incidence and mortality do not assume proportionality. Event times were defined relative to the date of randomization with censoring defined by end of follow-up, loss-to-follow-up, or death from causes other than breast cancer. Kaplan-Meier curves describe cumulative breast cancer hazard rates over time. Competing risk curves were also computed and were nearly identical to the Kaplan-Meier estimates.

For breast cancer incidence analyses, women who didn't consent to active follow-up after March 31, 2005 were censored at that time. The original consent permitted continued follow-up for vital status. Analyses for deaths from breast cancer for women who didn't re-consent were censored at December 31,2005, early in the re-consent period, since mortality data in this group may be incomplete at more recent times. Additional mortality analyses censored women not re-consenting on March 31, 2005.

Secondary analyses were conducted to examine the potential impact of censoring due to lack of re-consent on study findings. Several analyses were carried out, including comparison of re-consent rates by baseline characteristics and randomization assignment, and adjusted HR analyses using both inverse probability weighting and multiple imputation. The inverse probability weighting analyses developed a logistic regression model for re-consenting using baseline factors and randomization assignment. For the multiple imputation method invasive breast cancer events or censoring times were imputed for the 2620 eligible participants who did not re-consent (1333 intervention and 1287 placebo) beginning on March 31, 2005. Cox regression models were then fit for each of 25 imputed datasets and the resulting regression parameter estimates were averaged. Adherence sensitivity analyses for breast cancer mortality were conducted by censoring follow-up six months after a participant became non-adherent (using less than 80% of study pills or starting non-protocol hormone therapy). Six subgroups of clinical interest were identified post-hoc and examined for breast cancer hazard ratio variation. Less than one would be expected to be positive by chance alone.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute incorporated, Carry NC). All statistical tests were two sided. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00000611.

Results

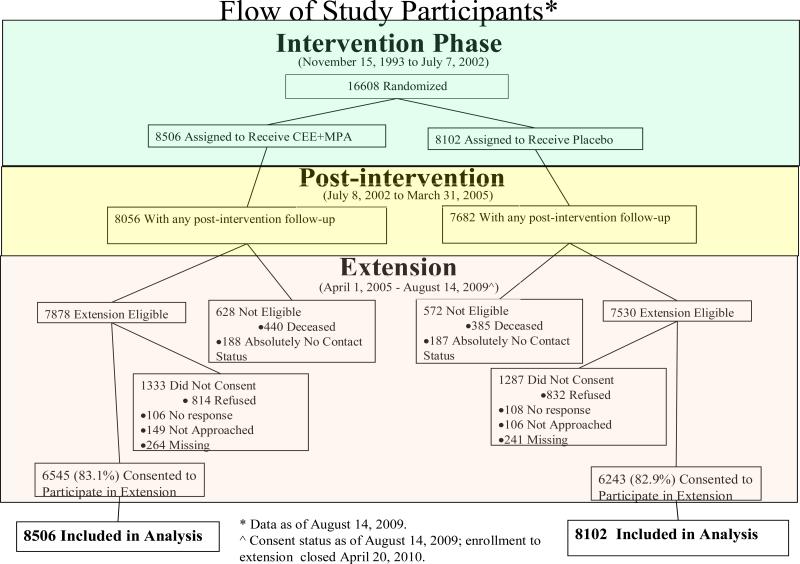

The flow of participants throughout the study is outlined in a CONSORT diagram (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics for the initially randomized 16,608 participants have been previously published (eTable 1). 1, 2 Participant characteristics in the two randomization groups were closely comparable in both the initial and in the re-consented populations (eTables 2, 3). Those re-consenting were slightly younger and more likely to be white compared to those not re-consenting. During the active intervention, study drugs were stopped at some time by 42% in the combined hormone and 38% in the placebo groups. 1

Figure 1.

Flow of study participants during the intervention, postintervention and extension phases. The post-intervention phase began on July 9, 2002 the day after participants were instructed to stop study medication use (conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate or placebo) use. The post-intervention phase continues thru the original trial completion date (March 31, 2005). The extension phase began on April 1, 2005, and includes follow-up for participants who re-consented (83% of those eligible) thru August 14, 2009.

eTable 1.

Baseline characteristics of all trial participants by randomization group (n=16608)

| Combined hormone therapy (n=8506) | Placebo (n=8102) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | P-Value | |

| Age group at screening | 0.79 | ||||

| 50-59 | 2837 | 33.4 | 2683 | 33.1 | |

| 60-69 | 3854 | 45.3 | 3655 | 45.1 | |

| 70-79 | 1815 | 21.3 | 1764 | 21.8 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.31 | ||||

| White | 7141 | 84.0 | 6805 | 84.0 | |

| Black | 548 | 6.4 | 574 | 7.1 | |

| Hispanic | 471 | 5.5 | 415 | 5.1 | |

| American Indian | 25 | 0.3 | 30 | 0.4 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 194 | 2.3 | 169 | 2.1 | |

| Unknown | 127 | 1.5 | 109 | 1.3 | |

| Education | 0.19 | ||||

| 0-8 years | 202 | 2.4 | 177 | 2.2 | |

| Some high school | 373 | 4.4 | 362 | 4.5 | |

| High school diploma/GED | 1615 | 19.1 | 1609 | 20.0 | |

| School after high school | 3357 | 39.7 | 3060 | 38.0 | |

| College degree or higher | 2915 | 34.4 | 2839 | 35.3 | |

| Gail 5year risk | 0.76 | ||||

| < 1.25 | 2806 | 33.0 | 2717 | 33.5 | |

| 1.25 - < 1.75 | 2859 | 33.6 | 2703 | 33.4 | |

| ≥ 1.75 | 2841 | 33.4 | 2682 | 33.1 | |

| Age at menarche | 0.83 | ||||

| ≤11 | 1725 | 20.3 | 1670 | 20.7 | |

| 12-13 | 4578 | 54.0 | 4334 | 53.7 | |

| ≥ 14 | 2182 | 25.7 | 2061 | 25.6 | |

| Years since menopause | 0.49 | ||||

| < 5 yrs | 1313 | 17.1 | 1225 | 16.3 | |

| 5 - <10 yrs | 1467 | 19.1 | 1486 | 19.8 | |

| 10 - <15 yrs | 1613 | 21.0 | 1567 | 20.9 | |

| ≥ 15 yrs | 3286 | 42.8 | 3230 | 43.0 | |

| Number of term pregnancies | 0.38 | ||||

| Never pregnant/Never had term pregnancy | 860 | 10.2 | 833 | 10.3 | |

| 1 | 690 | 8.1 | 661 | 8.2 | |

| 2 | 1908 | 22.5 | 1708 | 21.2 | |

| 3 | 2020 | 23.9 | 1952 | 24.2 | |

| 4 | 1416 | 16.7 | 1412 | 17.5 | |

| 5+ | 1575 | 18.6 | 1500 | 18.6 | |

| Age at first birth, y (categories) | 0.18 | ||||

| Never pregnant/No term pregnant | 860 | 11.2 | 833 | 11.5 | |

| < 20 | 1124 | 14.6 | 1117 | 15.4 | |

| 20 - 29 | 4996 | 64.8 | 4698 | 64.6 | |

| 30+ | 727 | 9.4 | 624 | 8.6 | |

| Number of months breastfed | 0.82 | ||||

| Never brstfd | 3813 | 45.3 | 3669 | 45.8 | |

| brstfd ≤ 1 year | 3150 | 37.5 | 2971 | 37.1 | |

| brstfd > 1 year | 1446 | 17.2 | 1366 | 17.1 | |

| Oral contraceptive use ever | 3695 | 43.4 | 3447 | 42.5 | 0.24 |

| Oral contraceptive duration | 0.25 | ||||

| < 5 yrs | 1982 | 53.7 | 1781 | 51.7 | |

| 5 - < 10 yrs | 825 | 22.3 | 808 | 23.5 | |

| ≥ 10 yrs | 886 | 24.0 | 855 | 24.8 | |

| HRT use status | 0.45 | ||||

| Never used | 6277 | 73.8 | 6022 | 74.4 | |

| Past user | 1671 | 19.7 | 1587 | 19.6 | |

| Current user | 554 | 6.5 | 490 | 6.1 | |

| Unopposed estrogen use ever | 903 | 10.6 | 865 | 10.7 | 0.90 |

| Unopposed estrogen use | 0.81 | ||||

| Non-user | 7603 | 89.4 | 7237 | 89.3 | |

| < 5 yrs | 677 | 8.0 | 659 | 8.1 | |

| ≥ 5 yrs | 226 | 2.7 | 205 | 2.5 | |

| Estrogen + progesterone use ever | 1516 | 17.8 | 1396 | 17.2 | 0.32 |

| Estrogen + Progest Duration | 0.27 | ||||

| Non-user | 6990 | 82.2 | 6706 | 82.8 | |

| < 5 yrs | 1050 | 12.3 | 997 | 12.3 | |

| ≥ 5 yrs | 466 | 5.5 | 399 | 4.9 | |

| Time since quitting HT | 0.58 | ||||

| Current | 554 | 6.5 | 490 | 6.1 | |

| Past, < 5 yrs | 726 | 8.5 | 673 | 8.3 | |

| Past, ≥ 5 yrs | 945 | 11.1 | 914 | 11.3 | |

| Never | 6277 | 73.8 | 6022 | 74.4 | |

| Number of first deg female relatives with breast cancer | 0.23 | ||||

| None | 6954 | 87.3 | 6676 | 88.2 | |

| 1 | 927 | 11.6 | 816 | 10.8 | |

| 2 or more | 82 | 1.0 | 79 | 1.0 | |

| Benign breast disease | 0.86 | ||||

| No | 6340 | 83.6 | 6278 | 83.3 | |

| Yes, 1 biopsy | 956 | 12.6 | 972 | 12.9 | |

| Yes, 2+ biopsies | 290 | 3.8 | 288 | 3.8 | |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2), baseline | 0.89 | ||||

| < 25 | 2579 | 30.4 | 2479 | 30.8 | |

| 25 - < 30 | 2992 | 35.3 | 2835 | 35.2 | |

| ≥ 30 | 2899 | 34.2 | 2737 | 34.0 | |

| Dietary energy(kcal) | 0.40 | ||||

| ≤ 1322 kcal | 2687 | 32.7 | 2610 | 33.3 | |

| 1322 < - 1841 kcal | 2779 | 33.8 | 2678 | 34.2 | |

| > 1841 kcal | 2752 | 33.5 | 2545 | 32.5 | |

| Percent energy from fat | 0.46 | ||||

| ≤ 29.6 percent | 2709 | 33.0 | 2588 | 33.0 | |

| 29.6 < - 37.2 percent | 2764 | 33.6 | 2694 | 34.4 | |

| > 37.2 percent | 2745 | 33.4 | 2551 | 32.6 | |

| Physical act (METS/wk) | 0.73 | ||||

| ≤ 3.5 METS/wk | 2658 | 34.6 | 2603 | 34.3 | |

| 3.5 < - 12.8 METS/wk | 2508 | 32.7 | 2467 | 32.5 | |

| > 12.8 METS/wk | 2505 | 32.7 | 2526 | 33.3 | |

| Alcohol use | 0.25 | ||||

| Non Drinker | 3601 | 42.5 | 3471 | 43.0 | |

| ≤ 1 drink/day | 3821 | 45.1 | 3546 | 44.0 | |

| > 1 drink/day | 1047 | 12.4 | 1048 | 13.0 | |

| Smoking status | 0.85 | ||||

| Never | 4178 | 49.6 | 3999 | 50.0 | |

| Past | 3362 | 39.9 | 3157 | 39.5 | |

| Current | 880 | 10.5 | 838 | 10.5 | |

| NSAIDs | 2853 | 33.5 | 2767 | 34.2 | 0.41 |

Due to information missing for some variables, category denominators do not alw ays equal group total shown in column heading.

Gail risk score incorporates age, history of benign disease (atypia staus unknown in the Women's Health Initiative), age at menarche, age at first live birth, race/ethnicity, and numbers of mothers and sisters with breast cancer

NSAIDs = use of aspirin, ibuprofen, prescription NSAIDs, or the related analgesic, acetaminophen

Time from menopause was defined as previously described15, as the interval from the onset of menopause to first menopausal hormone therapy use or first use of study medication (hormone or placebo).

eTable 2.

Baseline characteristics of trial participants that re-consented by randomization group (n=12788)

| Combined hormone therapy (n=6545) | Placebo (n=6243) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | P-Value | |

| Age group at screening | 0.75 | ||||

| 50-59 | 2266 | 34.6 | 2128 | 34.1 | |

| 60-69 | 3019 | 46.1 | 2887 | 46.2 | |

| 70-79 | 1260 | 19.3 | 1228 | 19.7 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.97 | ||||

| White | 5616 | 85.8 | 5357 | 85.8 | |

| Black | 406 | 6.2 | 401 | 6.4 | |

| Hispanic | 291 | 4.4 | 261 | 4.2 | |

| American Indian | 16 | 0.2 | 14 | 0.2 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 132 | 2.0 | 128 | 2.1 | |

| Unknown | 84 | 1.3 | 82 | 1.3 | |

| Education | 0.27 | ||||

| 0-8 years | 94 | 1.4 | 90 | 1.5 | |

| Some high school | 230 | 3.5 | 238 | 3.8 | |

| High school diploma/GED | 1254 | 19.3 | 1225 | 19.8 | |

| School after high school | 2569 | 39.5 | 2329 | 37.6 | |

| College degree or higher | 2363 | 36.3 | 2317 | 37.4 | |

| Gail 5year risk | 0.91 | ||||

| < 1.25 | 2117 | 32.3 | 2041 | 32.7 | |

| 1.25 - < 1.75 | 2237 | 34.2 | 2125 | 34.0 | |

| ≥ 1.75 | 2191 | 33.5 | 2077 | 33.3 | |

| Age at menarche | 0.79 | ||||

| ≤11 | 1372 | 21.0 | 1279 | 20.6 | |

| 12-13 | 3539 | 54.2 | 3377 | 54.3 | |

| ≥ 14 | 1617 | 24.8 | 1563 | 25.1 | |

| Years since menopause | 0.52 | ||||

| < 5 yrs | 1071 | 18.0 | 988 | 17.0 | |

| 5 - <10 yrs | 1199 | 20.2 | 1206 | 20.8 | |

| 10 - <15 yrs | 1267 | 21.3 | 1242 | 21.4 | |

| ≥ 15 yrs | 2410 | 40.5 | 2370 | 40.8 | |

| Number of term pregnancies | 0.37 | ||||

| Never pregnant/Never had term pregnancy | 661 | 10.1 | 627 | 10.1 | |

| 1 | 529 | 8.1 | 488 | 7.9 | |

| 2 | 1480 | 22.7 | 1319 | 21.2 | |

| 3 | 1573 | 24.1 | 1538 | 24.7 | |

| 4 | 1104 | 16.9 | 1103 | 17.7 | |

| 5+ | 1171 | 18.0 | 1140 | 18.3 | |

| Age at first birth, y (categories) | 0.30 | ||||

| Never pregnant/No term pregnant | 661 | 11.1 | 627 | 11.1 | |

| < 20 | 825 | 13.8 | 820 | 14.6 | |

| 20 - 29 | 3913 | 65.6 | 3702 | 65.7 | |

| 30+ | 564 | 9.5 | 482 | 8.6 | |

| Number of months breastfed | 0.96 | ||||

| Never brstfd | 2912 | 44.9 | 2782 | 45.1 | |

| brstfd ≤ 1 year | 2416 | 37.3 | 2285 | 37.0 | |

| brstfd > 1 year | 1152 | 17.8 | 1103 | 17.9 | |

| Oral contraceptive use ever | 2960 | 45.2 | 2789 | 44.7 | 0.53 |

| Oral contraceptive duration | 0.47 | ||||

| < 5 yrs | 1564 | 52.9 | 1438 | 51.6 | |

| 5 - < 10 yrs | 669 | 22.6 | 667 | 23.9 | |

| ≥ 10 yrs | 726 | 24.5 | 681 | 24.4 | |

| HRT use status | 0.64 | ||||

| Never used | 4798 | 73.3 | 4619 | 74.0 | |

| Past user | 1282 | 19.6 | 1200 | 19.2 | |

| Current user | 462 | 7.1 | 421 | 6.7 | |

| Unopposed estrogen use ever | 682 | 10.4 | 645 | 10.3 | 0.87 |

| Unopposed estrogen use | 0.88 | ||||

| Non-user | 5863 | 89.6 | 5598 | 89.7 | |

| < 5 yrs | 518 | 7.9 | 496 | 7.9 | |

| ≥ 5 yrs | 164 | 2.5 | 148 | 2.4 | |

| Estrogen + progesterone use ever | 1215 | 18.6 | 1131 | 18.1 | 0.51 |

| Estrogen + Progest Duration | 0.61 | ||||

| Non-user | 5330 | 81.4 | 5112 | 81.9 | |

| < 5 yrs | 840 | 12.8 | 798 | 12.8 | |

| ≥ 5 yrs | 375 | 5.7 | 333 | 5.3 | |

| Time since quitting HT | 0.80 | ||||

| Current | 462 | 7.1 | 421 | 6.7 | |

| Past, < 5 yrs | 576 | 8.8 | 531 | 8.5 | |

| Past, ≥ 5 yrs | 706 | 10.8 | 669 | 10.7 | |

| Never | 4798 | 73.3 | 4619 | 74.0 | |

| Number of first deg female relatives with breast cancer | 0.30 | ||||

| None | 5371 | 87.4 | 5149 | 88.1 | |

| 1 | 715 | 11.6 | 633 | 10.8 | |

| 2 or more | 58 | 0.9 | 63 | 1.1 | |

| Benign breast disease | 0.79 | ||||

| No | 4904 | 83.6 | 4843 | 83.2 | |

| Yes, 1 biopsy | 740 | 12.6 | 759 | 13.0 | |

| Yes, 2+ biopsies | 222 | 3.8 | 218 | 3.7 | |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2), baseline | 0.19 | ||||

| < 25 | 1998 | 30.7 | 1949 | 31.4 | |

| 25 - < 30 | 2278 | 35.0 | 2215 | 35.7 | |

| ≥ 30 | 2240 | 34.4 | 2038 | 32.9 | |

| Dietary energy(kcal) | 0.43 | ||||

| ≤ 1322 kcal | 1996 | 31.5 | 1966 | 32.4 | |

| 1322< - 1841 kcal | 2215 | 34.9 | 2117 | 34.9 | |

| > 1841 kcal | 2130 | 33.6 | 1980 | 32.7 | |

| Percent energy from fat | 0.44 | ||||

| ≤ 29.6 percent | 2157 | 34.0 | 2065 | 34.1 | |

| 29.6 < - 37.2 percent | 2114 | 33.3 | 2077 | 34.3 | |

| > 37.2 percent | 2070 | 32.6 | 1921 | 31.7 | |

| Physical act (METS/wk) | 0.46 | ||||

| ≤ 3.5 METS/wk | 1996 | 33.7 | 1913 | 32.7 | |

| 3.5 < - 12.8 METS/wk | 1940 | 32.8 | 1936 | 33.0 | |

| > 12.8 METS/wk | 1987 | 33.5 | 2010 | 34.3 | |

| Alcohol use | 0.76 | ||||

| Non Drinker | 2671 | 41.0 | 2559 | 41.1 | |

| ≤ 1 drink/day | 3003 | 46.1 | 2832 | 45.5 | |

| > 1 drink/day | 844 | 12.9 | 828 | 13.3 | |

| Smoking status | 0.94 | ||||

| Never | 3288 | 50.7 | 3139 | 50.9 | |

| Past | 2597 | 40.0 | 2452 | 39.8 | |

| Current | 600 | 9.3 | 577 | 9.4 | |

| NSAIDs | 2194 | 33.5 | 2133 | 34.2 | 0.44 |

Due to information missing for some variables, category denominators do not always equal group total shown in column heading.

Gail risk score incorporates age, history of benign disease (atypia staus unknown in the Women's Health Initiative), age at menarche, age at first live birth, race/ethnicity, and numbers of mothers and sisters with breast cancer

NSAIDs = use of aspirin, ibuprofen, prescription NSAIDs, or the related analgesic, acetaminophen

Time from menopause was defined as previously described15, as the interval from the onset of menopause to first menopausal hormone therapy use or first use of study medication (hormone or placebo).

eTable 3.

The number and percentage of all eligible participants from the original population that consented by baseline characteristics and randomization group

| Combined hormone therapy (n=7878 eligible) | Placebo (n=7530 eligible) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | P-Value | |

| Overall | 6545 | 83.1 | 6243 | 82.9 | 0.78 |

| Age group at screening | 0.86 | ||||

| 50-59 | 2266 | 84.0 | 2128 | 83.8 | |

| 60-69 | 3019 | 84.1 | 2887 | 84.3 | |

| 70-79 | 1260 | 79.2 | 1228 | 78.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.11 | ||||

| White | 5616 | 85.0 | 5357 | 84.5 | |

| Black | 406 | 80.2 | 401 | 77.1 | |

| Hispanic | 291 | 65.1 | 261 | 66.9 | |

| American Indian | 16 | 66.7 | 14 | 56.0 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 132 | 74.2 | 128 | 82.6 | |

| Unknown | 84 | 72.4 | 82 | 82.0 | |

| Education | 0.46 | ||||

| 0-8 years | 94 | 51.4 | 90 | 57.3 | |

| Some high school | 230 | 71.4 | 238 | 72.6 | |

| High school diploma/GED | 1254 | 83.7 | 1225 | 81.6 | |

| School after high school | 2569 | 82.5 | 2329 | 82.7 | |

| College degree or higher | 2363 | 86.8 | 2317 | 86.7 | |

| Gail 5 year risk | 0.54 | ||||

| < 1.25 | 2117 | 80.2 | 2041 | 80.1 | |

| 1.25 - < 1.75 | 2237 | 84.4 | 2125 | 85.0 | |

| ≥ 1.75 | 2191 | 84.7 | 2077 | 83.7 | |

| Age at menarche | 0.04 | ||||

| ≤11 | 1372 | 85.5 | 1279 | 82.5 | |

| 12-13 | 3539 | 83.4 | 3377 | 83.8 | |

| ≥ 14 | 1617 | 80.4 | 1563 | 81.6 | |

| Years since menopause | 0.54 | ||||

| < 5 yrs | 1617 | 85.3 | 1563 | 84.6 | |

| 5 - <10 yrs | 1071 | 86.3 | 988 | 85.4 | |

| 10 - <15 yrs | 1199 | 83.2 | 1206 | 84.7 | |

| ≥ 15 yrs | 1267 | 81.2 | 1242 | 80.5 | |

| Number of term pregnancies | 0.51 | ||||

| Never pregnant/Never had term pregnancy | 661 | 83.0 | 627 | 82.8 | |

| Mean ± SD | 529 | 83.0 | 488 | 80.1 | |

| Age at first birth, y (categories) | >0.99 | ||||

| Never pregnant/No term pregnant | 661 | 83.0 | 627 | 82.8 | |

| < 20 | 825 | 80.6 | 820 | 80.0 | |

| 20 - 29 | 3913 | 84.4 | 3702 | 84.1 | |

| 30+ | 564 | 84.3 | 482 | 83.7 | |

| Number of months breastfed | 0.70 | ||||

| Never brstfd | 2912 | 82.7 | 2782 | 81.8 | |

| brstfd ≤ 1 year | 2416 | 82.7 | 2285 | 83.0 | |

| brstfd > 1 year | 1152 | 85.6 | 1103 | 85.5 | |

| Oral contraceptive use ever | 2960 | 85.4 | 2789 | 85.7 | 0.50 |

| Oral contraceptive duration | 0.36 | ||||

| < 5 yrs | 1564 | 84.4 | 1438 | 85.7 | |

| 5 - < 10 yrs | 669 | 86.0 | 667 | 86.1 | |

| ≥ 10 yrs | 726 | 86.9 | 681 | 85.2 | |

| Unopposed estrogen use ever | 682 | 82.5 | 645 | 81.5 | 0.68 |

| Unopposed estrogen use | 0.59 | ||||

| Non-user | 5863 | 83.3 | 5598 | 81.3 | |

| < 5 yrs | 518 | 83.2 | 496 | 83.1 | |

| ≥ 5 yrs | 164 | 80.0 | 148 | 82.2 | |

| Estrogen + progesterone use ever | 1215 | 85.0 | 1131 | 85.9 | 0.40 |

| Estrogen + Progest Duration | 0.67 | ||||

| Non-user | 5330 | 82.6 | 5112 | 82.3 | |

| < 5 yrs | 840 | 84.4 | 798 | 85.3 | |

| ≥ 5 yrs | 375 | 86.4 | 333 | 87.6 | |

| Number of first deg female relatives with breast cancer | 0.74 | ||||

| None | 5371 | 84.9 | 5149 | 84.7 | |

| 1 | 715 | 83.1 | 633 | 82.8 | |

| 2 or more | 58 | 80.6 | 63 | 85.1 | |

| Benign breast disease | 0.89 | ||||

| No | 4904 | 83.1 | 4843 | 83.0 | |

| Yes, 1 biopsy | 740 | 84.6 | 759 | 83.6 | |

| Yes, 2+ biopsies | 222 | 82.2 | 218 | 81.3 | |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2), baseline | 0.03 | ||||

| < 25 | 1998 | 84.4 | 1949 | 84.1 | |

| 25 - < 30 | 2278 | 81.9 | 2215 | 83.6 | |

| ≥ 30 | 2240 | 83.1 | 2038 | 80.9 | |

| Dietary energy (kcal) | 0.96 | ||||

| ≤ 1322 kcal | 1996 | 80.8 | 1966 | 80.7 | |

| 1322 < - 1841 kcal | 2215 | 85.0 | 2117 | 85.2 | |

| > 1841 kcal | 2130 | 83.6 | 1980 | 83.6 | |

| Percent energy from fat | 0.78 | ||||

| ≤ 29.6 percent | 2157 | 85.5 | 2065 | 84.8 | |

| 29.6 < - 37.2 percent | 2114 | 82.8 | 2077 | 83.0 | |

| > 37.2 percent | 2070 | 81.3 | 1921 | 81.6 | |

| Physical act (METS/wk) | 0.85 | ||||

| ≤ 3.5 METS/wk | 1996 | 81.4 | 1913 | 80.5 | |

| 3.5 < - 12.8 METS/wk | 1940 | 83.7 | 1936 | 83.6 | |

| > 12.8 METS/wk | 1987 | 84.7 | 2010 | 84.7 | |

| Alcohol use | 0.54 | ||||

| Non Drinker | 2671 | 80.5 | 2559 | 80.3 | |

| ≤ 1 drink/day | 3003 | 84.4 | 2832 | 84.7 | |

| > 1 drink/day | 844 | 87.3 | 828 | 85.7 | |

| Smoking status | 0.63 | ||||

| Never | 3288 | 83.1 | 3139 | 83.3 | |

| Past | 2597 | 84.1 | 2452 | 83.9 | |

| Current | 600 | 79.4 | 577 | 77.3 | |

| NSAIDs | 2194 | 83.5 | 2133 | 83.4 | 0.96 |

Due to information missing for some variables, category denominators do not always equal group total shown in column heading.

Gail risk score incorporates age, history of benign disease (atypia staus unknown in the Women's Health Initiative), age at menarche, age at first live birth, race/ethnicity, and numbers of mothers and sisters with breast cancer

NSAIDs = use of aspirin, ibuprofen, prescription NSAIDs, or the related analgesic, acetaminophen

Time from menopause was defined as previously described15, as the interval from the onset of menopause to first menopausal hormone therapy use or first use of study medication (hormone or placebo).

As seen, consent rates were comparable for demographic and risk factor distribution for the two randomization groups.

Mammography frequency was comparable in the two randomization groups during the original trial period thru March 31, 2005 (annualized %, 80% vs 80% for hormone vs placebo, respectively). In the re-consented population in the extension phase, the percentage of women with one or more mammograms was also comparable in the randomization groups (86% vs 86% for hormone vs placebo, respectively).

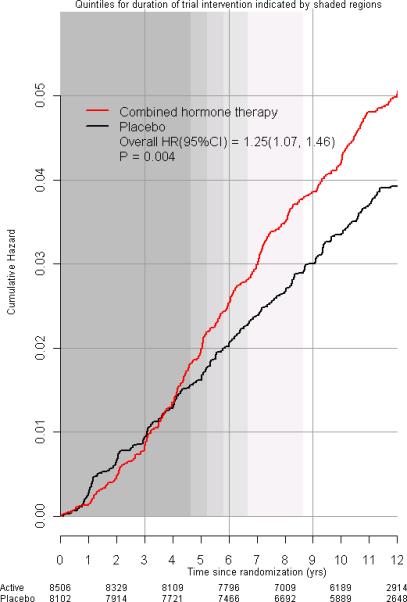

The mean follow-up period (intervention plus post intervention) (SD) was 11.0 years (2.7) with a range of 0.1 to15.3 years) representing a total of 170,166 woman-years of follow-up. In intent-to-treat analysis, estrogen plus progestin increased invasive breast cancer incidence (385 [0.42% per year] vs 293 [0.34% per year] cases, respectively, HR 1.25; 95% CI 1.07-1.46, P=0.004) compared with placebo (Figure 2). Also depicted are quintiles of duration of study intervention indicated by the progressive shaded regions (representing 4.6, 5.2, 5.8, 6.7 and 8.6 years, respectively) based on the participant's time of entry on study and the end of study intervention.

Figure 2.

Incidence of invasive breast cancer in the WHI clinical trial. Intent-to-treat Kaplan Meier cumulative hazard curves for incidence of invasive breast cancer by study group and time since randomization. Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values are from Cox regression models, stratified by age (5 year intervals) and randomization assignment in the WHI Dietary Modification trial. Quintiles of duration on study intervention (elapsed time from randomization until the intervention stopped on July 8, 2002) are indicated by the progressive shaded regions. For example, 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% of participants were in the intervention for at least 4.6 years, 5.2 years, 5.8 years and 6.7 years, respectively. All women stopped the intervention by 8.6 years (when shading ends).

A significantly larger fraction of breast cancers presented with positive lymph nodes in the combined hormone therapy compared to the placebo group 23.7% vs 16.2%,respectively, HR 1.78; 95% CI 1.23-2.58. There was no evidence of a differential effect of combined hormone therapy on receptor positive versus receptor negative tumors. Somewhat more tumors overexpressed HER 2 and were triple negative in the hormone therapy compared to placebo group (Table 1). However, as routine clinical determination of HER 2 status was introduced during the study course, missing values for this parameter were not uncommon.

Table 1.

Invasive breast cancer characteristics by study groups

| Combined Hormone Therapy (n=385 invasive breast caners) | Placebo (n=293 invasive breast caners) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | P-Value1 | |

| Tumor size, mean (SD), cm | 1.7 | (1.3) | 1.5 | (1.1) | 0.11 |

| Tumor size | 0.34 | ||||

| No tumor found/no primary mass | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Microscopic focus or foci | 9 | 2.5 | 15 | 5.5 | |

| ≤ 0.5 cm | 38 | 10.5 | 27 | 9.9 | |

| >0.5 - 1 cm | 92 | 25.3 | 84 | 30.7 | |

| >1 - 2 cm | 146 | 40.2 | 98 | 35.8 | |

| >2 cm | 77 | 21.2 | 48 | 17.5 | |

| Lymph nodes examined | 0.80 | ||||

| No | 39 | 10.3 | 28 | 9.6 | |

| Yes2 | 341 | 89.7 | 263 | 90.4 | |

| Number of positive lymph nodes | 0.06 | ||||

| None | 258 | 76.3 | 218 | 83.8 | |

| 1-3 | 60 | 17.8 | 34 | 13.1 | |

| >3 | 20 | 5.9 | 8 | 3.1 | |

| Positive lymph nodes | 0.03 | ||||

| No | 258 | 76.1 | 218 | 83.5 | |

| Yes3 | 81 | 23.9 | 43 | 16.5 | |

| SEER – stage | 0.05 | ||||

| Localized | 288 | 75.2 | 238 | 81.2 | |

| Regional | 86 | 22.5 | 46 | 15.7 | |

| Distant | 5 | 1.3 | 7 | 2.4 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.7 | |

| SEER stage (regional/distant) | 0.07 | ||||

| No | 288 | 76.0 | 238 | 81.8 | |

| Yes | 91 | 24.0 | 53 | 18.2 | |

| Histology | 0.41 | ||||

| Ductal | 238 | 62.1 | 195 | 66.6 | |

| Lobular | 36 | 9.4 | 20 | 6.8 | |

| Ductal and Lobular | 57 | 14.9 | 35 | 11.9 | |

| Tubular | 13 | 3.4 | 9 | 3.1 | |

| Other | 39 | 10.2 | 34 | 11.6 | |

| Grade | 0.51 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 100 | 26.1 | 67 | 22.9 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 140 | 36.6 | 116 | 39.6 | |

| Poorly differentiated/anaplastic | 92 | 24.0 | 77 | 26.3 | |

| Unknown | 51 | 13.3 | 33 | 11.3 | |

| Estrogen receptor | 0.81 | ||||

| Positive | 308 | 80.0 | 230 | 78.5 | |

| Negative | 48 | 12.5 | 33 | 11.3 | |

| Borderline | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Unknown/Not Done/Missing | 29 | 7.5 | 29 | 9.9 | |

| Progesterone receptor | 0.92 | ||||

| Positive | 262 | 68.1 | 194 | 66.2 | |

| Negative | 86 | 22.3 | 62 | 21.2 | |

| Borderline | 5 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| Unknown/Not Done/Missing | 32 | 8.3 | 34 | 11.6 | |

| HER2 overexpression | 0.17 | ||||

| Yes | 54 | 14.0 | 26 | 8.9 | |

| No | 233 | 60.5 | 161 | 54.9 | |

| Borderline | 3 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Unknown/Not Done/Missing | 95 | 24.7 | 105 | 35.8 | |

| Triple negative tumor | 0.61 | ||||

| Triple negative(ER-/PR-/HER2-) | 26 | 6.8 | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Other (includes borderline) | 259 | 67.3 | 173 | 59.0 | |

| Unknown/Missing ER/PR/HER2 all/some | 100 | 26.0 | 106 | 36.2 | |

P-value based on Fisher's exact test of association. Bracket indicates the subset of categories for a tumor characteristic that were tested for association with randomization assignment. If there is no bracket, then all categories for a tumor characteristic were tested for association with tumor characteristic.

Ten instances (5 active and 5 placebo) where lymph nodes were examined but number examined was not specified.

Two instances (1 active and 1 placebo) where positive nodes determined but number of positive nodes not specified.

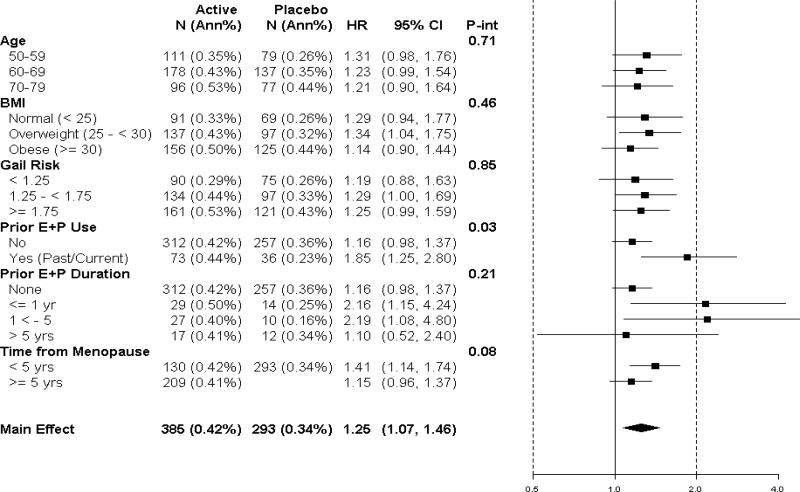

In subgroup analyses, no significant interventions were seen among estrogen plus progestin use and breast cancer incidence with age, BMI, and Gail risk score (Figure 3). For women entering with no prior estrogen plus progestin use, HR was 1.16; 95% CI 0.98-1.37 compared to a HR of 1.85; 95% CI 1.25-2.80 for those with prior combined hormone therapy use (interaction P=0.03). The breast cancer incidence HR for women with < 1 year of prior estrogen plus progestin use was 2.16; 95% CI 1.15-4.24 (Figure 3). Women who first used hormone therapy closer to menopause (< 5 years) were at somewhat greater risk of developing breast cancer in the combined hormone therapy group but the interaction term was not significant (P=0.08).

Figure 3.

Invasive breast cancer incidence by baseline characteristics and study group. Hazard ratios (combined hormone therapy vs. placebo) are from a Cox regression models stratified by age and randomization assignment in the dietary modification (DM) trial. For subgroup analyses, HR are allowed to vary by subgroup, and Cox regression models are stratified by age, randomization assignment in the WHI Dietary Modification trial, and subgroup. P-values are from Cox regression models for a 1-df test for trend. “Current use” refers to those reporting combined hormone therapy use at time of initial evaluation. A 3 month “wash out” was required before study entry. The time from menopause variable defined as the interval from the onset of menopause until first menopausal hormone therapy use or first study medication use (combined hormone therapy or placebo).

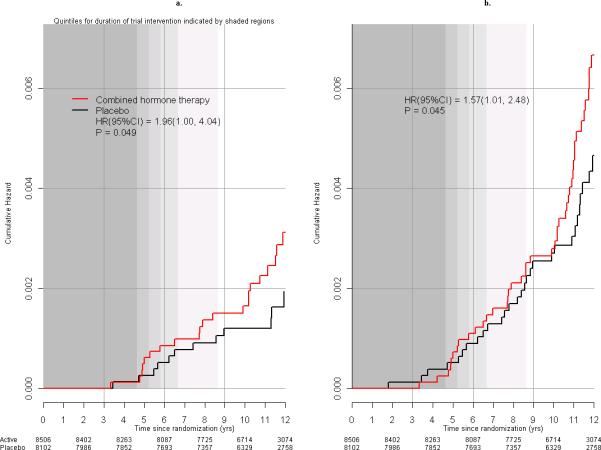

More women died from breast cancer in the combined hormone therapy compared to placebo groups (25 [0.03% per year] vs 12 [0.01% per year] deaths, HR 1.96; 95% CI 1.00-4.04, P=0.049) (Figure 4A) representing 2.6 vs 1.3 deaths per 10,000 women per year, respectively. Restriction of the follow-up time to March 31, 2005 for women not re-consenting did not change the death from breast cancer finding (HR 1.96; 95% CI 1.01-4.05, P=0.048). Consideration of all-cause mortality after breast cancer diagnosis also provides similar results for the combined hormone therapy use (51 [0.05% per year] vs 31 [0.03% per year] deaths, respectively HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.01-2.48, P=0.045) (Figure 4B) representing 5.3 vs 3.4 deaths per 10,000 women per year, respectively.

Figure 4.

Deaths after breast cancer in the WHI clinical trial. Kaplan Meier cumulative hazard curves for: A) deaths directly attributed to breast cancer by study group and time since randomization and B) deaths from all causes following a breast cancer diagnosis, by study group and time in the trial. Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values are from Cox regression models, stratified by age (5 year intervals) and randomization assignment in the WHI Dietary Modification trial. Quintiles for duration of study intervention (elapsed time from randomization, until the intervention stopped on July 8, 2002) are indicated by the progressive shaded regions. For example, 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% of participants were in the intervention for at least 4.6 years, 5.2 years, 5.8 years and 6.7 years, respectively. All women stopped the intervention by 8.6 years.

Sensitivity analyses also suggest an adverse effect of combined hormone therapy on breast cancer mortality when follow-up times for each women are censored at non-adherence (14 vs 5 deaths, respectively, HR; 2.96; 95% CI 1.00-8.77, P=0.053). Inverse probability weighting and multiple imputation analyses to address potential imbalance associated with re-consent supports the primary analyses suggesting an elevation in deaths from breast cancer with estrogen plus progestin (inverse probability weighing summary HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.07-4.59; multiple imputation summary HR 2.12; 95% CI 1.02-4.40).

Discussion

In the WHI randomized placebo-controlled trial, conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate increased invasive breast cancer incidence and the cancers were more commonly node positive. There were more deaths attributed to breast cancer (2.6 vs 1.3 per 10,000 women per year) and more deaths from all causes in women following a diagnosis of breast cancer (5.3 vs 3.4 per 10,000 women per year) in the combined hormone therapy group.

With some exceptions, 8, 9 the preponderance of observational studies have associated combined hormone therapy use with an increase in breast cancers which have favorable characteristics, 7 lower stage 5, 10 and longer survival compared to breast cancers diagnosed in non-users of hormone therapy 7, 10 However, in the WHI randomized trial, combined hormone therapy increased breast cancer risk and interfered with breast cancer detection leading to cancers diagnosed at more advanced stage. 2, 3 Now with longer follow-up, there remains a cumulative, statistically significant increase in breast cancers in the combined hormone therapy group and the cancers more commonly had lymph node involvement. The observed adverse influence on breast cancer mortality with combined hormone therapy can reasonably be explained by the influence on breast cancer incidence and stage.

The discrepancy between the current randomized clinical trial findings and observational studies with respect to breast cancer mortality likely are related to potential confounding in observational analyses. Observational studies which begin analyses at breast cancer diagnosis and adjust for stage 7, 18 potentially adjust away unfavorable consequences of estrogen plus progestin use. Menopausal hormone therapy users have mammography at more regular intervals than non-users, 19, 20 likely related to breast cancer concerns. Studies unable to control for mammography can be confounded by differences between screen detected and non-screen detected breast cancers. Screening more commonly identifies slow growing, favorable grade, hormone receptor positive breast cancers and diagnoses them at earlier stage. 21-23 Our findings are consistent with the observational Million Women Study where mammography was controlled and breast cancer mortality analyses began at cohort entry rather than diagnosis. There combined hormone therapy use was associated with higher breast cancer mortality (HR 1.22; 95% CI 1.00-1.48, P=0.05). 10

Following the initial report 1of this trial, a substantial decrease in breast cancer incidence occurred in the U.S. which was attributed 24, 25 to the marked decrease in menopausal hormone therapy use that occurred. 26 The adverse influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer mortality suggests that a future reduction in breast cancer mortality in the U.S. may be anticipated as well.

Accurate determination of cause of death after a breast cancer diagnosis is problematic given the potential interaction between common co-morbidities and cancer treatments. 27 Thus, the actual mortality risk related to breast cancer likely lies somewhere between the medical record attributed risk and consideration of all mortality following breast cancer diagnoses.

The relative influence of combined hormone therapy on both breast cancer mortality, in this report, and on lung cancer mortality, 28 was greater than its influence on cancer incidence. Reproductive hormones 29, 30 and especially progestin 31 are potent angiogenesis stimulators. Since increased angiogenesis increases both lung 33 and breast cancer metastases, 34 these findings suggest that angiogenesis stimulation by combined hormone therapy facilitates growth and metastatic spread of already established cancers. Unless the mortality risks of lung cancer and breast cancer can be mitigated, continued consideration of combined menopausal hormone therapy use for other than short term therapy in women with limiting climacteric symptoms not amendable to other therapies seems unwarranted.

The WHI trial results evaluating estrogen plus progestin have been generally accepted by health regulatory agencies. However, some continue to question the applicability of the results to current clinical practice 35, 36 emphasizing potential differences in coronary heart disease risk when hormone therapy is begun shortly after menopause. 15, 37 However, both prior analyses 38 and current analyses reflecting longer follow-up in this trial suggest a somewhat greater adverse hormonal effect on breast cancer incidence in women randomized closer to menopause with similar findings seen in the French E3N observational cohort. 39 Additionally, current analyses support our prior suggestion that durations of use only slightly longer than those in the trial are associated with increases in breast cancer risk. 40 Given these findings and the effect of combined hormone therapy to delay breast cancer diagnosis, 2, 3 a safe interval for combined hormone therapy use for breast cancer cannot be reliably defined.

Study strengths include the randomized, double-blind study design, a large and ethnically diverse study population, serial assessment of mammography and clinical breast exams, central adjudication of breast cancers, and the long follow-up. The lack of breast cancer therapy information and the modest number of deaths in women diagnosed with breast cancer are limitations as is the difficulty in attributing cause of death in breast cancer patients. For breast cancer mortality analyses, the wide confidence intervals with lower limits close to 1.0 imply some caution in interpretation. The relatively modest duration of study estrogen plus progestin use was limited by the net adverse effect of combined hormone therapy on clinical outcomes.

The decision to follow-up participants after the original study completion date for disease incidence required re-consent. The fact that 17% of women didn't re-consent may have influenced the estimation of combined hormone therapy's effect on breast cancer. However, in both the original randomized group and in the re-consented group, baseline characteristics were comparable in the hormone therapy and placebo groups. In addition, inverse probability weighting and multiple imputation analyses to address this concern result in similar findings regarding estrogen plus progestin use and deaths from breast cancer.

In conclusion, estrogen plus progestin use increases the incidence of breast cancers and the cancers are more commonly node positive. Mortality data analyses suggest that breast cancer mortality may also be increased.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the dedicated efforts of investigators and staff at the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) clinical centers, the WHI Clinical Coordinating Center, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood program office (listing available at http://www.whi.org). We recognize the WHI participants for their extraordinary commitment to the WHI program. The Women's Health Initiative program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221. The investigators and staff were compensated. The study participants were not compensated.

Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Elizabeth Nabel, Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Nancy Geller, Leslie Ford.

Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA)

Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Ruth Patterson, Anne McTiernan, Barbara Cochrane, Julie Hunt, Lesley Tinker, Charles Kooperberg, Martin McIntosh, C. Y. Wang, Chu Chen, Deborah Bowen, Alan Kristal, Janet Stanford, Nicole Urban, Noel Weiss, Emily White; (Medical Research Laboratories, Highland Heights, KY) Evan Stein, Peter Laskarzewski; (San Francisco Coordinating Center, San Francisco, CA) Steven R. Cummings, Michael Nevitt, Lisa Palermo; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Lisa Harnack; (Fisher BioServices, Rockville, MD) Frank Cammarata, Steve Lindenfelser; (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) Bruce Psaty, Susan Heckbert.

Clinical Centers: (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, William Frishman, Judith Wylie-Rosett, David Barad, Ruth Freeman; (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) Aleksandar Rajkovic, Jennifer Hays, Ronald Young, Haleh Sangi-Haghpeykar; (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson, Kathryn M. Rexrode, Brian Walsh, J. Michael Gaziano, Maria Bueche; (Brown University, Providence, RI) Charles B. Eaton, Michele Cyr, Gretchen Sloane; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) Lawrence Phillips, Vicki Butler, Vivian Porter; (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Shirley A.A. Beresford, Vicky M. Taylor, Nancy F. Woods, Maureen Henderson, Robyn Andersen; (George Washington University, Washington, DC) Lisa Martin, Judith Hsia, Nancy Gaba, Richard Katz; (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Research and Education Institute, Torrance, CA) Rowan Chlebowski, Robert Detrano, Anita Nelson, Michele Geller; (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR) Yvonne Michael, Evelyn Whitlock, Victor Stevens, Njeri Karanja; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA) Bette Caan, Stephen Sidney, Geri Bailey Jane Hirata; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) Jane Morley Kotchen, Vanessa Barnabei, Theodore A. Kotchen, Mary Ann C. Gilligan, Joan Neuner; (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard, Lucile Adams-Campbell, Lawrence Lessin, Cheryl Iglesia, Linda K Mickel; (Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL) Linda Van Horn, Philip Greenland, Janardan Khandekar, Kiang Liu, Carol Rosenberg; (Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL) Henry Black, Lynda Powell, Ellen Mason; Martha Gulati; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick, Mark A. Hlatky, Bertha Chen, Randall S. Stafford, Sally Mackey; (State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY) Dorothy Lane, Iris Granek, William Lawson, Catherine Messina, Gabriel San Roman; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson, Randall Harris, Electra Paskett, W. Jerry Mysiw, Michael Blumenfeld; (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) Cora E. Lewis, Albert Oberman, James M. Shikany, Monika Safford; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A Thomson, Tamsen Bassford, Cheryl Ritenbaugh, Zhao Chen, Marcia Ko; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende, Maurizio Trevisan, Ellen Smit, Susan Graham, June Chang; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) John Robbins, S. Yasmeen; (University of California at Irvine, CA) F. Allan Hubbell, Gail Frank, Nathan Wong, Nancy Greep, Bradley Monk; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA) Lauren Nathan, David Heber, Robert Elashoff, Simin Liu; (University of California at San Diego, LaJolla/Chula Vista, CA) Robert D. Langer, Michael H. Criqui, Gregory T. Talavera, Cedric F. Garland, Matthew A. Allison; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) Margery Gass, Nelson Watts; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher, Michael Perri, Andrew Kaunitz, R. Stan Williams, Yvonne Brinson; (University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI) J. David Curb, Helen Petrovitch, Beatriz Rodriguez, Kamal Masaki, Patricia Blanchette; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace, James Torner, Susan Johnson, Linda Snetselaar, Jennifer Robinson; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA) Judith Ockene, Milagros Rosal, Ira Ockene, Robert Yood, Patricia Aronson; (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ) Norman Lasser, Baljinder Singh, Vera Lasser, John Kostis, Peter McGovern; (University of Miami, Miami, FL) Mary Jo O'sullivan, Linda Parker, JoNell Potter, Diann Fernandez, Pat Caralis; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Karen L. Margolis, Richard H. Grimm, Mary F. Perron, Cynthia Bjerk, Sarah Kempainen; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner, William Graettinger, Vicki Oujevolk, Michael Bloch; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) Gerardo Heiss, Pamela Haines, David Ontjes, Carla Sueta, Ellen Wells; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller, Jane Cauley, N. Carole Milas; (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN) Karen C. Johnson, Suzanne Satterfield, Rongling Li, Stephanie Connelly, Fran Tylavsky; (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) Robert Brzyski, Robert Schenken; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) Gloria E. Sarto, Douglas Laube, Patrick McBride, Julie Mares, Barbara Loevinger; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Mara Vitolins, Greg Burke, Robin Crouse, Scott Washburn; (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI) Michael Simon.

Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker, Stephen Rapp, Claudine Legault, Mark Espeland, Laura Coker.

Former Principal Investigators and Project Officers: (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) Jennifer Hays, John Foreyt; (Brown University, Providence, RI) Annlouise R. Assaf; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) Dallas Hall; (George Washington University, Washington, DC) Valery Miller; (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR) Barbara Valanis; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA) Robert Hiatt; (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) Carolyn Clifford1; (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Linda Pottern; (University of California at Irvine, CA) Frank Meyskens, Jr.; (University of California at Los Angeles, CA) Howard Judd1; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) James Liu, Nelson Watts; (University of Miami, Miami, FL) Marianna Baum, (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Richard Grimm; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Sandra Daugherty1; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) David Sheps, Barbara Hulka; (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN) William Applegate; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) Catherine Allen1; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Denise Bonds.

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221.

Footnotes

Disclosure:

Dr Chlebowski reports that he has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer, and lecture fees from AstraZeneca and Novartis and grant funding from Amgen. Dr. Gass reports that she has received funding for multisite clinical trials from Procter and Gamble and Wyeth Laboratories, and consulting fees from Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and Procter and Gamble. Dr. Rohan has received consulting fees from legal firms regarding hormone therapy issues. Dr. Hendrix reports that she has received consulting fees from Meditrina Pharmaceuticals Inc, lecture fees from Merck & Company and grant funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, and Organon. Otherwise, no other authors report financial conflicts.

Role of the funding source

The study sponsor had input into the design and conduct of the study and participated in the report review, but did not participate in preparation of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility to submit for publication.

References

- 1.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3243–3253. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Pettinger M, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer detection by means of mammography and breast biopsy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):370–377. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chlebowski RT, Kuller LH, Prentice RL, et al. Breast cancer after estrogen plus progestin use in postmenopausal women. New Eng J Med. 2009;360(6):573–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holi K, Isola J, Cuzick J. Low biologic aggressiveness in breast cancer in women using hormone replacement therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(9):3115–3120. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen WY, Hankinson SE, Schnitt SJ, Rosner BA, Holmes MD, Colditz GA. Association of hormone replacement therapy to estrogen and progesterone receptor status in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:1490–500. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg LU, Granath F, Dickman PW, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy in relation to breast cancer characteristics and prognosis: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Research. 2008;10:R78. doi: 10.1186/bcr2145. 10 November 18, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beral V. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362(9382):419–427. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Prognostic characteristics of breast cancer among postmenopausal hormone users in a screened population. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(23):4314–4321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newcomb PA, Egan KM, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Prediagnostic use of hormone therapy and mortality after breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(4):864–71. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christante D, Pommier S, Garreau J, Muller P, LaFleur B, Pommier R. Improved breast cancer survival among hormone replacement therapy users is durable after 5 years of additional follow-up. Am J Surg. 2008;196:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Women's Health Initiative Study Group Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbel FA, et al. The Women's Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13((9)(suppl)):S18–S77. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, et al. Implementation of the Women's Health Initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;297:1465–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curb D, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women's Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 suppl):S122–S128. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [September 24, 2009];National Cancer. 2006 http://seer.cancer.gov/.

- 18.Sener SF, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP, et al. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on postmenopausal breast cancer biology and survival. Am J Surg. 2009;197(3):403–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joffe MM, Byrne C, Colditz GA. Postmenopausal hormone use, screening and breast cancer characterization and control of a bias. Epidemiology. 2001;12(4):429–38. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen Y, Yang Y, Inoue LYT, Munsell MF, Miller AB, Berry DA. Role of detection method in predicting breast cancer survival: analysis of randomized screening trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1195–1203. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sihto H, Lundin J, Lehtimaki T, et al. Molecular subtypes of breast cancers detected in mammography screening and outside of screening. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4103–4110. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong W, Berry DA, Bevers TB, et al. Prognostic role of detection method and its relationship with tumor biomarkers in breast cancer: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(5):1096–1103. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Uratsu CT, Selby JV, Kushi LH, Herrinton LJ. Recent declines in hormone therapy utilization and breast cancer incidence: clinical and population-based evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):e49–e50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6504. letter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravdin PM, Cronin K, Howlander N, et al. A sharp decrease in breast cancer incidence in the United States in 2003. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(16):1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of menopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinder MC, Duan Z, Goodwin JS, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3808–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chlebowski RT, Schwartz AG, Wakelee H, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and lung cancer in postmenopausal women (Women's Health Initiative trial): a post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1243–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61526-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Losordo DW, Isner JM. Estrogen and angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:6–12. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobrzcka B, Kinalski M, Piechocka D, Terlikowski SJ. The role of estrogens in angiogenesis in the female reproductive system. Endokrynol Pol. 2009;60:210–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang Y, Besch-Williford C, Brekken RA, Hyder SM. Progestin-dependent progression of human breast tumor Xenografts: a novel model for evaluating anti-tumor therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9929–9936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyder SM, Murthy L, Stancel GM. Progestin regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58(3):392–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calvo A, Catena R, Noble MS, et al. Identification of VEGF-regulated genes associated with increased lung metastatic potential: functional involvement of tenascin-C in tumor growth and lung metastasis. Oncogene. 2008;27(40):5373–84. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WE, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastases: correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Power ML, Anderson BL, Schulkin J. Attitudes of obstetrician-gynecologists toward the evidence from the Women's Health Initiative hormone therapy trials remain generally skeptical. Menopause. 2009;16(3):500–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818fc36e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevenson JC, Hodis HN, Pickar JH, Lobo RA. Coronary heart disease and menopause management: the swinging pendulum of HRT. Artherosclerosis. 2009 Jun 9; doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.033. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toh S, Hernandez-Diaz S, Logan R, Rossouw JE, Hernan MA. Coronary heart disease in postmenopausal recipients of estrogen plus progestin therapy: Does the increased risk ever disappear? Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:211–217. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prentice RL, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Estrogen plus progestin therapy and breast cancer in recently postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1207–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fournier A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F. Estrogen progestagen menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer: does delay from menopause onset to treatment initiation influence risks? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5138–5143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Rossouw JE, et al. Prior hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin. Maturitas. 2006;55(2):103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]