Abstract

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 (APE-1) is a key enzyme responsible for DNA base excision repair and is also a multifunctional protein such as redox effector for several transcriptional factors. Our study was designed to investigate APE-1 expression and to study its interaction with cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression and VEGF production in the esophageal cancer. The expression of APE-1, COX-2, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, CC-chemokine receptor (CCR)2, and VEGF were evaluated by immunohistochemistry in 65 human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissues. Real-time PCR and Western blotting were performed to detect mRNA and protein expression of APE-1 and p-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) expression in MCP-1-stimulated ESCC cell lines (KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10). siRNA for APE-1 was treated to determine the role of APE-1 in the regulation of COX-2 expression, VEGF production, and antiapoptotic effect against cisplatin. In human ESCC tissues, nuclear localization of APE-1 was observed in 92.3% (60/65) of all tissues. There was a significant relationship (P = 0.029, R = 0.49) between nuclear APE-1 and cytoplasmic COX-2 expression levels in the esophageal cancer tissues. In KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells, MCP-1 stimulation significantly increased mRNA and protein expression of APE-1. Treatment with siRNA for APE-1 significantly inhibited p-STAT3 expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated cells. Furthermore, treatment of siRNA for APE-1 significantly reduced COX-2 expression and VEGF production in MCP-1-stimulated esophageal cancer cell lines. Treatment with APE-1 siRNA significantly increased apoptotic levels in cisplatin-incubated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells. We concluded that APE-1 is overexpressed and associated with COX-2 expression and VEGF production in esophageal cancer tissues.

Keywords: apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1, esophageal cancer, cyclooxygenase-2, vascular endothelial growth factor, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

esophageal carcinogenesis induced by ethanol and smoking is closely related to the metabolism of ethanol, acetaldehyde, and acetate, and the carcinogens in smoke, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and N-nitrosamines, respectively. These factors generate cytokines, prostaglandins, and reactive oxygen/nitrogen species in esophageal tissues. The host response to free radical-induced damage includes the induction of DNA repair enzymes, such as apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease -1 (APE-1) (7, 21). APE-1 is also a multifunctional protein such as a redox effector for several transcriptional factors including activator protein (AP)-1, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1-α, and p53 (1). The presence of AP sites is known to block DNA synthesis or lead to mutations or genetic instability (20). If the function of base excision repair is suppressed due to reduced APE-1 activity, sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy is increased (32). In addition, Zou et al. (37) have reported that APE-1-specific inhibitor, E3330, reduced tumorigenesis through inhibition of VEGF production (37). There are no available data, then, about the APE-1 expression and distribution in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) protein plays important roles in development of gastrointestinal cancers (34). Many studies have reported that COX-2 is associated with tumorigenesis through angiogenesis and reduction of apoptosis (5, 29, 31). We have also reported that a selective COX-2 inhibitor significantly reduced the incidence of gastric cancer in methylnitrosourea-treated Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-infected Mongolian gerbils (8). In esophageal cancer tissues, COX-2, VEGF, and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 were predictive factors for severe prognosis and resistance against chemotherapy (4, 24, 36). Moreover, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, also inhibited APE-1 expression through reduction of IkBα phosphorylation (8). Therefore, it is a critical issue for understanding the precise mechanism for development of esophageal cancer to clarify the relationship between COX-2 and APE-1 expression. In addition, the MCP-1 receptor, CC-chemokine receptor (CCR)2, also has been reported to impact on angiogenesis and VEGF production (23, 26) as well as MCP-1, which plays a pivotal role in tumor vascularity of esophageal cancer (24).

Given the role that APE-1 may play in the development of esophageal cancer, we examined the coexpression of APE-1 and COX-2 expression as one predictive factor in esophageal cancer tissues and determined whether APE-1 was associated with VEGF production in the development of esophageal cancer tissues through induction of COX-2 protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

A total of 65 paraffin-embedded esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissues were obtained from archived patients with esophageal cancer who had undergone esophagectomies and/or received chemoradiotherapy in Nippon Medical School Hospital. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Among these patients, there were 47 males and 18 females, ranging in age from 50–86 yr. Sixty-five tissues were categorized according to UICC (International Union Against Cancer) TNM classification as follows: 3 stage 0, 10 stage I, 10 stage IIA, 1 stage IIB, 19 stage III, 5 stage IVA, 17 stage IVB.

Cell culture and treatments.

ESCC cell lines, KYSE 220, and EC-GI-10 (purchased from National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Osaka, Japan) were maintained in RPMI 1640 or Ham F12 (Nikken Bio Medical Laboratory, Nagoya, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Nippon Bio-Supply Center, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Group 1 without any treatments served as the control, group 2 was stimulated by human recombinant MCP-1 (0.1 μmol/l) without pretreatment of siRNA for APE-1, whereas group 3 was stimulated by MCP-1 (0.1 μmol/l) after 24-h pretreatment with siRNA for APE-1. Cisplatin (0, 1, 3, and 6 μl/ml) was then added to the KYSE220 cells with or without pretreatment of siRNA for APE-1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of APE-1, COX-2, MCP-1, CCR2, and VEGF.

Expression of APE-1, COX-2, MCP-1, CCR2, and VEGF in the esophageal cancer tissues was evaluated by immunostaining. Briefly, 4-μm sections were deparaffinized, antigens were retrieved by microwaving for 5 min in 5% urea solution, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 in methanol. The samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-APE-1 antibody (diluted 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-COX-2 antibody (diluted 1: 150; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), rabbit anti-MCP-1 antibody (diluted 1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-CCR2 antibody (diluted 1:20; Abcam), and anti-VEGF antibody (diluted 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After being washed, the secondary antibody was detected by LSAB 2 kit (DAKO) with diaminobenzidine as chromogen. For the negative control, primary antibodies were replaced with isotype-matched immunoglobulin.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence methods and confocal laser scanning microscopy were used to evaluate the coexpression of immunoreactivity for the pair of mouse anti-human COX-2 (diluted 1:40; Cayman Chemical) and rabbit anti-human APE-1 (diluted 1:20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mixture of the two primary antibodies and then with FITC or Texas red-conjugated secondary antibodies [horse anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories), for COX-2 and APE-1, respectively] followed by nuclear counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

The immunostaining scoring system as follows was established by experienced pathologists. For APE-1, immunoreactivity was graded from 0 to 3 (0:0%, 1:0∼33%, 2:33∼66%, 3:67∼100%) based on the proportion of positive nuclei to total cell number in representative areas of the cancer tissue (9). For COX-2, immunoreactivity was determined by the intensity of staining and the percentage of areas with positive staining. The intensity of staining was graded from 0 to 3, and the area of positivity was estimated as a percentage of total area of the tumor. These two variables constituted the actual score: 0, 1, 2, 3, as described previously (22). Six fields were selected to determine the average score of APE-1 and COX-2. For MCP-1, sections with more than 30% positive cells were considered positive, whereas the sections with 30% or less positive cells were considered negative, as described previously (24). Since Kitadai et al. (17) have reported that MCP-1 was significantly correlated with VEGF immunoreactivity in esophageal cancer tissues (positive staining for VEGF was defined as the presence of VEGF immunoreactivity >30% of esophageal cancer cells), we have also determined the definition of MCP-1 positivity based on previous studies (24).

Western blotting analysis of APE-1 and p-STAT3 expression levels in treated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells.

Stimulated [H2O2: (200 μmol/l); MCP-1 (0.03, 0.1 and 0.3 μmol/l)] KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells were lysed in a buffer solution containing 0.1% NP-40, 10 nM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 nM Na2HPO4, 65 mM Na-orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor cocktail. APE-1 protein, partially purified, was visualized by Western blotting. Briefly, equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 and incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-APE-1 (diluted 1: 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (diluted 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and mouse anti-β-actin (diluted 1: 1,000; Sigma) antibodies, and, after being washed, they were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (diluted 1:1,000; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 1 h at room temperature. Electrochemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) was used for detection.

Real-time PCR of APE-1 expression levels in treated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells.

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed to detect mRNA expression levels of APE-1 from MCP-1-stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells. Briefly, RNA extracted from these cells was reverse-transcribed, and subsequently cDNA was amplified in 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with primers, dual-labeled fluorogenic probes, and a TaqMan PCR Reagent kit (Applied Biosystems). The primers and probes for APE-1 (accession no. Hs00172396-ml*), COX-2 (accession no. Hs00153133-m1*), and β-actin (accession no. Hs99999903-ml*) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Known concentrations of serially diluted APE-1, COX-2, and β-actin cDNA generated by PCR were used as standards for quantification of sample cDNA. Copy numbers of cDNA for APE-1 and COX-2 were standardized to that of β-actin for the same sample.

RNA interference siRNA-APE-1 in KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells.

For siRNA transfection, KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells were inoculated at the density of 6 × 104/ml in RPMI-1640 medium without 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. A cell suspension of 1.0 ml per well was seeded in 24-well plates. The siRNAs were synthesized corresponding to human APE-1 (accession nos.: HSS 100555; HSS 100556; HSS 100557; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and one nonsilencing siRNA was supplied as a control (control siRNA). The nonsilencing control siRNA was synthesized using scrambled sequences.

Transfection of siRNAs and control siRNA into KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). Briefly, 6 pmol siRNAs (final concentration 10–50 nM) and 1.5 μl of Lipofectamine were used for each well. siRNAs and Lipofectamine were first diluted in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (Invitrogen), respectively, and then mixed and incubated for 20 min at room temperature for complex formation. Next, the entire mixture was added to the cells in the wells. At 24 h after transfection, the cells of 24-well plates were used for real-time PCR for COX-2.

Assessment of apoptosis.

To determine apoptosis, stimulated-KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells were treated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme with incubation in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 1 h. Apoptosis was evaluated using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay analysis (ApopTag; Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD). To evaluate the degree of apoptosis, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was counted within a ×400 field. Four fields were selected to determine the average score count. Data were expressed as the mean percentage of total cell number (apoptotic index).

Statistical analysis.

Mann-Whitney U-test was used for analysis of categorical data, and Student's t-test was used for analysis of continuous data. One-way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine factors associated with high APE-1 expression. Results were expressed as the means ± SD, and a P value <0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Localization of APE-1, MCP-1, CCR2, COX-2, and VEGF in the esophageal cancer tissues.

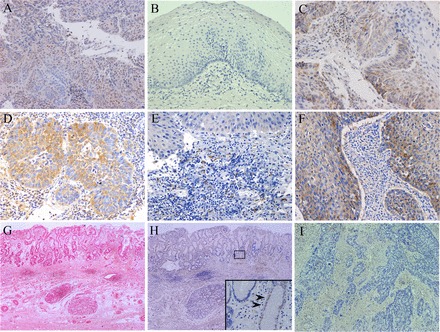

In human ESCC tissues, nuclear localization APE-1 was observed in 92.3% (60/65) of all tissues (Fig. 1A). In contrast, in normal esophageal tissues, APE-1 expression could not be observed (Fig. 1B). COX-2, MCP-1, and CCR-2 were primarily expressed in the cytoplasmic compartment in the esophageal cancer cells (Fig. 1, C–E). VEGF was also expressed in the cytoplasm in esophageal cancer cells (Fig. 1F). Specialized columnar epithelial cells could be seen in Barrett's epithelium (Fig. 1G). APE-1 was expressed at low levels in specialized columnar epithelial cells in Barrett's epithelium (Fig. 1H). In addition, staining could not be seen in esophageal cancer tissues using control IgG antibody (Fig. 1I).

Fig. 1.

Localization of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 (APE)-1, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, CC-chemokine receptor 2(CCR2), and VEGF in esophageal cancer tissues. APE-1- (A), COX-2- (C), MCP-1- (D), CCR2- (E), and VEGF-positive cells (F) in esophageal cancer tissues were identified by immunohistochemistry. B: APE-1-positive cells were not detected in normal esophageal mucosa. (Magnification ×125 for A, E, F, ×150 for B, C, and D). G: specialized columnar epithelial cells could be seen in Barrett's epithelium (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification, ×80). H: APE-1 was observed at low levels in specialized columnar epithelial cells in Barrett's epithelium (original magnification, ×80). Arrows show APE-1 immunoreactivity in a faint nuclear pattern. I: staining was not seen in esophageal cancer tissues incubated with control IgG antibody (original magnification, ×200).

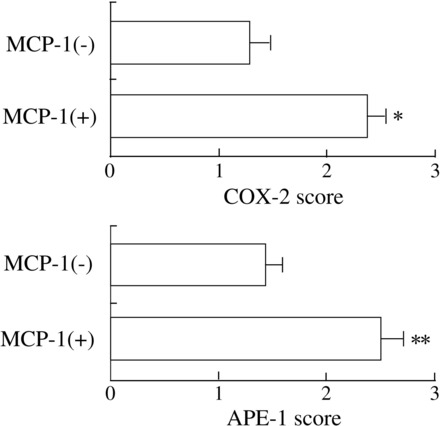

COX-2 and APE-1 protein expression levels in MCP-positive esophageal cancer tissues.

Because MCP-1 has been reported to play important roles in tumorigenesis in esophageal cancer tissues, we determined whether MCP-1 was associated with APE-1 and COX-2 expression in esophageal cancer tissues. In immunohistochemical analysis, both APE-1 and COX-2 expression scores in MCP-1-positive esophageal cancer tissues (n = 41) were significantly (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, respectively) greater compared with MCP-1-negative esophageal cancer tissues (n = 24) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

COX-2 and APE-1 protein expression levels in MCP-1-positive esophageal cancer tissues. Expression levels of APE-1 and COX-2 in MCP-1-positive esophageal cancer tissues (n = 41) were significantly higher compared with MCP-1-negative tissues (n = 24) (*P < 0.001; **P < 0.001, respectively). Data are expressed as means ± SE of each score in 65 esophageal cancer tissues.

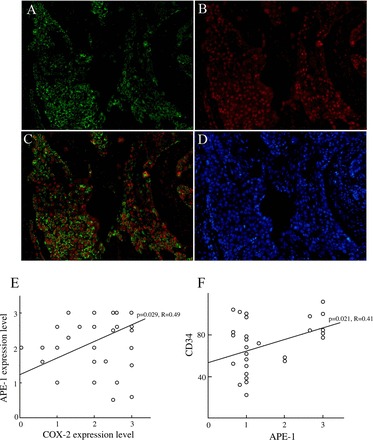

Correlation between COX-2 and APE-1 expression in esophageal cancer tissues.

Because APE-1 and COX-2 were strongly expressed in the esophageal cancer tissues, in this study, we determined the relationship between COX-2 and APE-1 expression levels in esophageal cancer tissues. FITC-labeled (green) cells in the esophageal cancer tissues in Fig. 3A show COX-2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 3A). Texas red-conjugated cells in Fig. 3B show APE-1 immunoreactivity for the same section (Fig. 3B). There were a few double-positive-stained cells (yellow cells) for the same section (Fig. 3C). However, we have addressed that nuclear APE-1 and cytoplasmic COX-2 expressions were mainly coexpressed in the esophageal cancer tissues (Fig. 3C). In addition, we observed a significant relationship (P = 0.029, R = 0.49) between COX-2 and APE-1 expression levels in 65 esophageal cancer tissues (Fig. 3E). Moreover, we have also determined that there was a significant relationship (P = 0.021, R = 0.41) between APE-1 and CD34-positive cells in esophageal cancer tissues (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

The relationship between APE-1 and COX-2 expression in esophageal cancer tissues. A: COX-2-positive cells (green cells) in the esophageal cancer tissues (original magnification, ×150). B: APE-1-positive cells (red cells) in the esophageal cancer tissues (original magnification, ×150). C: nuclear APE-1 and cytoplasmic COX-2 expressions were mainly coexpressed in the same section. Double-positive cells (yellow cells) reveal COX-2-and APE-1-positive cells in the same section (original magnification, ×150). D: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (blue cells) (original magnification, ×150). E: there was a significant relationship (P = 0.029) between APE-1 and COX-2 expressions in the 65 patients with esophageal cancer. F: there was a significant relationship (P = 0.021, R = 0.41) between APE-1 and CD34-positive cells in the esophageal cancer tissues.

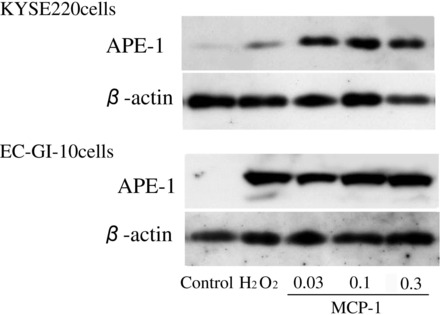

APE-1 expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated esophageal cancer cell lines.

To clarify whether MCP-1 stimulation induced APE-1 expression in esophageal cancer tissues, we examined APE-1 expression levels induced by H2O2 and MCP-1 stimulation in esophageal cancer cell line, KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells, by Western blotting analysis. H2O2 (200 μmol/l) and MCP-1 (0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 μmol/l) stimulations increased APE-1 protein expression in both cell lines (Fig. 4). APE-1 expression was also observed in 200 μmol/l H2O2-stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells. APE-1 protein levels were low in unstimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

APE-1 expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated KYSE 220 cells. APE-1 expression levels in H2O2 (200 μmol/l) and MCP-1(0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 μmol/l)-stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells were significantly increased compared with unstimulated group.

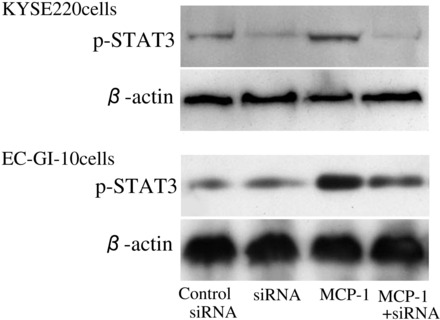

p-STAT3 expression levels in stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells treated with siRNA for APE-1.

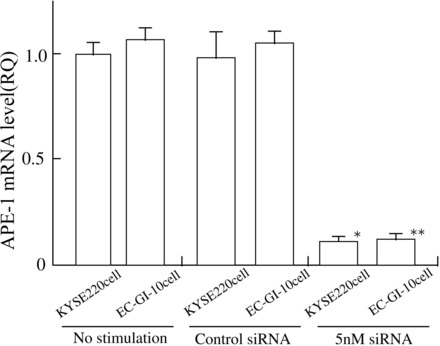

To clarify whether APE-1 action had an effect on STAT3 activation in esophageal cancer cells, we examined p-STAT3 expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells treated with siRNA for APE-1. Treatment with siRNA for APE-1 completely suppressed APE-1 mRNA levels in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells by real-time PCR measurement (Fig. 5). Treatment with siRNA for APE-1 significantly inhibited p-STAT3 expression levels in MCP-1 stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Treatment with siRNA for APE-1 in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells. Treatment with 5 nM siRNA for APE-1 in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells completely suppressed APE-1 mRNA levels. *P < 0.01 vs. control nonsilencing siRNA treated KYSE 220 cells or unstimulated KYSE 220 cells. **P < 0.01 vs. control nonsilencing siRNA-treated EC-GI-10 cells or unstimulated EC-GI-10 cells.

Fig. 6.

p-STAT3 expression levels in stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells treated with siRNA for APE-1. p-STAT3 expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated KYSE 220 cells and EC-GI-10 cells treated with 5 nM siRNA for APE-1 were significantly reduced compared with MCP-1-stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells.

COX-2 mRNA expression and VEGF production in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells treated with siRNA for APE-1.

To determine the role of APE-1 in the regulation of COX-2 expression, we measured COX-2 mRNA levels in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells treated with siRNA for APE-1. MCP-1 stimulation significantly increased COX-2 mRNA expression levels compared with those in unstimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells, as well as control nonsilencing siRNA- and siRNA-treated cells. siRNA (5 nM) for APE-1 significantly reduced the expression of COX-2 mRNA levels and VEGF production in MCP-1-treated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells compared with in MCP-1-treated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7, A and B). SiRNA treatment for APE-1 could not significantly reduce COX-2 levels in unstimulated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells (Fig. 7A). In contrast, 5 nM siRNA treatment for APE-1 also significantly inhibited VEGF production in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells compared with those in control nonsilencing siRNA-treated and -unstimulated cells (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Expression of COX-2 mRNA levels and VEGF production in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells treated with siRNA. A: 5 nM siRNA for APE-1 significantly reduced COX-2 mRNA expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells. B: 5 nM siRNA for APE-1 significantly reduced VEGF production in MCP-1-treated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells. 5 nM siRNA treatment for APE-1 also significantly inhibited VEGF production in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells compared with those in control nonsilencing siRNA-treated and -unstimulated cells. Data are expressed as means ± SE of 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.001 vs. 5 nM siRNA for APE-1-treated cells, 5 nM siRNA for APE-1 treatment in MCP-1-stimulated cells, control siRNA-treated cells or -unstimulated cells. **P < 0.05 vs. control siRNA-treated cells or -unstimulated cells.

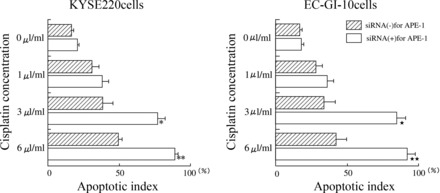

Apoptosis levels in cisplatin-incubated esophageal cancer cell lines treated with siRNA for APE-1.

To clarify the mechanism by which APE-1 activity was associated with sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy, we investigated levels of apoptosis in cisplatin-incubated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells with or without siRNA for APE-1. siRNA for APE-1 treatment significantly increased apoptotic levels in cisplatin (3 μl/ml and 6 μl/ml)-incubated KYSE220 cells (Fig. 8, left) and EC-GI-10 cells (Fig. 8, right).

Fig. 8.

Apoptosis levels in cisplatin-incubated esophageal cancer cell lines treated with siRNA for APE-1. Left: siRNA for APE-1 treatment significantly (*P < 0.05) increased apoptotic levels in cisplatin (3 μl/ml and 6 μl/ml)-incubated KYSE220 cells. Right: siRNA for APE-1 treatment significantly (**P < 0.05) increased apoptotic levels in cisplatin (3 μl/ml and 6 μl/ml)-incubated EC-GI-10 cells. Data are expressed as means ± SE of 4 separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to investigate the localization of APE-1 expression in esophageal cancer tissues and to determine whether APE-1 was associated with development of esophageal cancer through elevation of COX-2 expression and VEGF production. Our major findings are as follows: 1) APE-1 was overexpressed and found primarily in esophageal cancer cells with nuclear localization; 2) a significant relationship between APE-1 and COX-2 expression scores in esophageal cancer tissues was demonstrated; 3) MCP-1 stimulation significantly increased APE-1 protein level in KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells; and 4) reduction of APE-1 by specific siRNA significantly reduced COX-2 mRNA expression levels and VEGF production in MCP-1-stimulated KYSE 220 cells.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of APE-1 overexpression and a significant relationship between COX-2 and APE-1 in esophageal cancer tissues. Previous studies have shown that overexpression of APE-1 was associated with resistance to chemoradiotherapy in HeLa cells (12), glioma cell (27), medulloblastoma, and primitive neuroectodermal tumors (3), as well as nonsmall cell lung cancer (33). Overexpression of APE-1 is found in many kinds of malignancies of digestive tract-associated organs, including cytoplasmic expression of APE-1 in colorectal cancer (16), hepatocellular carcinoma (6), and nuclear expression in pancreatic cancer (15). Our results demonstrate that APE-1 was not detected in normal esophageal tissues, but it was expressed in 73.3% of cells in esophageal cancer tissues with nuclear localization of APE-1 observed in 92.3% (60/65) of these tissues. The nuclear localization of APE-1 may be associated with chemoradiotherapy resistance and a poor survival (18).

Previous studies have reported that MCP-1 is expressed in esophageal cancer tissues and plays a pivotal role in tumorigenesis of esophageal cancer (24). Because we found that APE-1 expression levels in MCP-1-positive esophageal cancer were significantly increased compared with those with MCP-1-negative esophageal cancer, we investigated whether APE-1 expression levels were affected by MCP-1 stimulation using Western blotting analysis. We showed that APE-1 expression in KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells was increased by MCP-1 stimulation. Our results suggest that MCP-1 may play an important role in APE-1 induction in esophageal cancer tissues. Further studies are needed to clarify the relationship between MCP-1 and APE-1 expression in esophageal cancer tissues.

In immunohistochemical analysis, there was a significant relationship between COX-2 and APE-1 in esophageal cancer tissues. We have previously reported that a selective COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, inhibited APE-1 expression via reduction of IkBα phosphorylation (8). We have recently reported that MG-132, an NF-κB inhibitor, abrogated the p65 and APE-1 expression levels in MCP-1-stimulated esophageal cancer cell lines (28). In addition, APE-1 has been reported to stimulate the DNA binding activity of NF-κB. Therefore, reduction of APE-1 in stimulated esophageal cancer cell lines could lead to inhibition of stimulated COX-2 expression through downregulation of NF-κB activation. However, in this study, basal COX-2 expression levels in unstimulated esophageal cancer cell lines such as KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells were not affected by siRNA treatment for APE-1 through reduction of DNA binding activity of NF-κB. Constitutive basal COX-2 expression levels in unstimulated esophageal cancer cell lines might be partly induced in NF-κB-independent pathway as previously reported (13). Previous studies have reported that APE-1 interacts with HIF-1α, STAT3, and activates hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF (10, 35). In this study, we have also reported that inhibition of APE-1 expression was associated with reduction of p-STAT3 expression levels in stimulated esophageal cancer cell lines. Zou et al. (37) have also reported that the APE-1-specific inhibitor, E-3330m inhibited tumorigenesis via reduction of growth of endothelial cells and VEGF production (37), and, in another report, inhibition of APE-1 was associated with reduction of angiogenesis in vitro (14). In addition, Hall et al. (11) have also reported that APE-1 is also cytoprotective against endothelial apoptosis induced by hypoxia and by tumor necrosis factor-α, through the transcriptional upregulation of NF-κB-dependent survival signals, as well as NF-κB-independent mechanism. Previous studies and our study suggest that inhibition of APE-1 were partly linked to the reduction of VEGF production through reduction of activation of STAT3. In addition, although, in our data, there was not colocalization of APE-1 and CD34 in esophageal cancer tissues, we have also demonstrated that APE-1 expression levels were significantly associated with CD34 expression levels in esophageal cancer tissues. Collectively, these results suggest that APE-1 may be modulated to prevent the development of esophageal cancer through reduction of angiogenesis.

APE-1 overexpression has been reported to be associated with resistance to various anticancer drugs. Several studies have shown that targeted reduction of APE-1 protein by specific antisense oligo or siRNA sensitized to methylmethane sulfonate, H2O2, bleomycin, and gemcitabine (3, 19, 25, 30). Whether such enhanced sensitivity is solely due to the loss of the DNA repair activity of APE-1 or also due to the loss of its transcriptional regulatory function or both is still unknown. Our data showed that, in APE-siRNA-treated KYSE220 and EC-GI-10 cells, the antiapoptotic function of APE-1 against cisplatin was abolished. Hall et al. (11) have reported that deletion of the redox-sensitive domain of APE-1 reduced the antiapoptotic function of APE-1 in both hypoxia and tumor necrosis factor-α-induced endothelial cell death (11). Furthermore, Bhattacharyya et al. (2) reported that H. pylori-mediated acetylation of APE-1 suppressed Bax expression and prevented p53-mediated apoptosis. Although there were relatively few (n = 23) patients treated with chemoradiotherapy, we found a negative trend (P = 0.09, R = 0.512) between effective ratio against chemoradiotherapy and APE-1 expression levels in esophageal cancer tissues. Further studies will be needed to clarify whether APE-1 expression is associated with chemoresistance in esophageal cancer tissues. Taken together with these prior reports, our results suggest that APE-1 affects development of esophageal cancer through upregulation of VEGF production and reduction of apoptosis.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that a significant relationship exists between APE-1 and COX-2 expression in esophageal cancer tissues. Moreover, reduction of APE-1 by specific siRNA significantly reduced COX-2 mRNA expression levels and VEGF production in MCP-1-stimulated KYSE 220 and EC-GI-10 cells. We believe that a greater understanding of the role of COX-2 in the regulation of APE-1 expression could provide potential future therapeutic targets in esophageal cancer.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhakat K, Mantha A, Mitra S. Transcriptional regulatory functions of mammalian AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1), an essential multifunctional protein. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 621–638, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya A, Chattopadhyay R, Burnette BR, Cross JV, Mitra S, Ernst PB, Bhakat KK, Crowe SE. Acetylation of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 regulates Helicobacter pylori-mediated gastric epithelial cell apoptosis. Gastroenterology 136: 2258–2269, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bobola MS, Finn LS, Ellenbogen RG, Geyer JR, Berger MS, Braga JM, Meade EH, Gross ME, Silber JR. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease activity is associated with response to radiation and chemotherapy in medulloblastoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Clin Cancer Res 11: 7405–7414, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Cai E, Huang J, Yu P, Li K. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21: 1126–1134, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dempke W, Rie C, Grothey A, Schmoll HJ. Cyclooxygenase-2: a novel target for cancer chemotherapy? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 127: 411–417, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Maso V, Avellini C, Crocè LS, Rosso N, Quadrifoglio F, Cesaratto L, Codarin E, Bedogni G, Beltrami CA, Tell G, Tiribelli C. Subcellular localization of APE1/Ref-1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma: possible prognostic significance. Mol Med 13: 89–96, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung H, Demple B. A vital role for Ape1/Ref1 protein in repairing spontaneous DNA damage in human cells. Mol Cell 17: 463–470, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Futagami S, Kawagoe T, Horie A, Shindo T, Hamamoto T, Suzuki K, Kusunoki M, Miyake K, Gudis K, Tsukui T, Crowe SE, Sakamoto C. Celecoxib inhibits apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 expression and prevents gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. Digestion 78: 93–102, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Futagami S, Hiratsuka T, Shindo T, Horie A, Hamamoto T, Suzuki K, Kusunoki M, Miyake K, Gudis K, Crowe SE, Tsukui T, Sakamoto C. Expression of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 (APE-1) in H. pylori-associated gastritis, gastric adenoma, and gastric cancer. Helicobacter 13: 209–218, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray MJ, Zhang J, Ellis LM, Semenza GL, Evans DB, Watowich SS, Gallick GE. HIF-1alpha, STAT3, CBP/p300 and Ref-1/APE are components of a transcriptional complex that regulates Src-dependent hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF in pancreatic and prostate carcinomas. Oncogene 24: 3110–3120, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall JL, Wang X, Van Adamson Zhao Y, Gibbons GH. Overexpression of Ref-1 inhibits hypoxia and tumor necrosis factor-induced endothelial cell apoptosis through nuclear factor-kappab-independent and -dependent pathways. Circ Res 88: 1247–1253, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen WK, Deutsch WA, Yacoub A, Xu Y, Williams DA, Kelley MR. Creation of a fully functional human chimeric DNA repair protein. Combining O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) and AP endonuclease (APE/redox effector factor 1 (Ref 1)) DNA repair proteins. J Biol Chem 273: 756–762, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husvik C, Bryne M, Halstensen TS. Epidermal growth factor-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines is mediated through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 but is Src and nuclear factor-kappa B independent. Eur J Oral Sci 117: 528–535, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang A, Gao H, Kelley MR, Qiao X. Inhibition of APE1/Ref-1 redox activity with APX3330 blocks retinal angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Vision Res 51: 93–100, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Y, Zhou S, Sandusky GE, Kelley MR, Fishel ML. Reduced expression of DNA repair and redox signaling protein APE1/Ref-1 impairs human pancreatic cancer cell survival, proliferation, and cell cycle progression. Cancer Invest 28: 885–895, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakolyris S, Kaklamanis L, Engels K, Turley H, Hickson ID, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Human apurinic endonuclease 1 expression in a colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Cancer Res 57: 1794–1797, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitadai Y, Haruma K, Tokutomi T, Tanaka S, Sumii K, Carvalho M, Kuwabara M, Yoshida K, Hirai T, Kajiyama G, Tahara E. Significance of vessel count and vascular endothelial growth factor in human esophageal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 4: 2195–2200, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Kakolyris S, Sivridis E, Georgoulias V, Funtzilas G, Hickson ID, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Nuclear expression of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (HAP1/Ref-1) in head-and-neck cancer is associated with resistance to chemoradiotherapy and poor outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50: 27–36, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau JP, Weatherdon KL, Skalski V, Hedley DW. Effects of gemcitabine on APE/ref-1 endonuclease activity in pancreatic cancer cells, and the therapeutic potential of antisense oligonucleotides. Br J Cancer 91: 1166–1173, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loeb LA, Preston BD. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu Rev Genet 20: 201–230, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo M, Delaplane S, Jiang A, Reed A, He Y, Fishel M, Nyland RL, 2nd, Borch RF, Qiao X, Georgiadis MM, Kelley MR. Role of the multifunctional DNA repair and redox signaling protein Ape1/Ref-1 in cancer and endothelial cells: small-molecule inhibition of the redox function of Ape1. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 1853–1867, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mrena J, Wiksten JP, Thiel A, Kokkola A, Pohjola L, Lundin J, Nordling S, Ristimäki A, Haglund C. Cyclooxygenase-2 is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer and its expression is regulated by the messenger RNA stability factor HuR. Clin Cancer Res 11: 7362–7368, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochoa O, Sun D, Reys-Reyna SM, Waite LL, Michalek JE, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Delayed angiogenesis and VEGF production in CCR2−/− mice during impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R651–R661, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohta M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Yasui W, Mukaida N, Haruma K, Chayama K. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with macrophage infiltration and tumor vascularity in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer 102: 220–224, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono Y, Furuta T, Ohmoto T, Akiyama K, Seki S. Stable expression in rat glioma cells of sense and antisense nucleic acids to a human multifunctional DNA repair enzyme, APEX nuclease. Mutat Res 315: 55–63, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salcedo R, Ponce ML, Young HA, Wasserman K, Ward JM, Kleinman HK, Oppenheim JJ, Murphy WJ. Human endothelial cells express CCR2 and respond to MCP-1: direct role of MCP-1 in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Blood 96: 34–40, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silber JR, Bobola MS, Blank A, Schoeler KD, Haroldson PD, Huynh MB, Kolstoe DD. The apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease activity of Ape1/Ref-1 contributes to human glioma cell resistance to alkylating agents and is elevated by oxidative stress. Clin Cancer Res 8: 3008–3018, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song J, Futagami S, Nagoya H, Kawagoe T, Yamawaki H, Kodaka Y, Tatsuguchi A, Gudis K, Wakabayashi T, Yonazawa M, Shimpuku M, Watarai Y, Iwakiri K, Hoshihara Y, Makino H, Miyashita M, Tsuchiya S, Li Y, Crowe SE, Sakamoto C. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 (APE-1) is overexpressed via the activation of NF-kB-p65 in MCP-1-positive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma tissue. J Clin Biochem Nutr 52: 112–119, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toomey DP, Murphy JF, Conlon KC. COX-2, VEGF and tumour angiogenesis. Surgeon 7: 174–180, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker LJ, Craig RB, Harris AL, Hickson ID. A role for the human DNA repair enzyme HAP1 in cellular protection against DNA damaging agents and hypoxic stress. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4884–4889, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang D, Dubois RN. Prostaglandins and cancer. Gut 55: 115–122, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Luo M, Kelley MR. Human apurinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) expression and prognostic significance in osteosarcoma: enhanced sensitivity of osteosarcoma to DNA damaging agents using silencing RNA APE1 expression inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther 3: 679–686, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D, Xiang DB, Yang XQ, Chen LS, Li MX, Zhong ZY, Zhang YS. APE1 overexpression is associated with cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer and targeted inhibition of APE1 enhances the activity of cisplatin in A549 cells. Lung Cancer 66: 298–304, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu WK, Sung JJ, Lee CW, Yu J, Cho CH. Cyclooxygenase-2 in tumorigenesis of gastrointestinal cancers: an update on the molecular mechanisms. Cancer Lett 295: 7–16, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziel KA, Campbell CC, Wilson GL, Gillespie MN. Ref-1/Ape is critical for formation of the hypoxia-inducible transcriptional complex on the hypoxic response element of the rat pulmonary artery endothelial cell VEGF gene. FASEB J 18: 986–988, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann KC, Sarbia M, Weber AA, Borchard F, Gabbert HE, Schrör K. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Res 59: 198–204, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zou GM, Karikari C, Kabe Y, Handa H, Anders RA, Maitra A. The Ape-1/Ref-1 redox antagonist E3330 inhibits the growth of tumor endothelium and endothelial progenitor cells: therapeutic implications in tumor angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol 219: 209–218, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]