Abstract

Background

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a significant cause of disability in young adults. Hip arthroscopic surgery restores bony congruence and improves function in the majority of patients, but recent evidence indicates that women may experience worse pre- and postoperative function than men.

Purpose/Hypothesis

The purpose of this study was to identify whether self-reported hip function differed between men and women with symptomatic FAI. The hypothesis was that mean self-reported hip function scores would improve after arthroscopic surgery but that women would report poorer function than men both before and up to 2 years after arthroscopic surgery.

Study Design

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 2.

Methods

A total of 229 patients (68.4% women; mean [±SD] age, 31.6 ± 10.8 years; mean [6SD] body mass index, 26.8 ± 11.9 kg/m2) underwent hip arthroscopic surgery for unilateral symptomatic FAI. All eligible and consenting patients with radiologically and clinically confirmed FAI completed the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33) and the Hip Outcome Score activities of daily living subscale (HOS-ADL) before hip arthroscopic surgery and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after arthroscopic surgery. A linear mixed model for repeated measures was used to test for differences in self-reported hip function between men and women over the study period (P ≤ .05).

Results

There were no significant time × sex interactions for either the HOS-ADL (P = .12) or iHOT-33 (P = .64), but both measures showed significant improvements between the preoperative time point and each of the 4 follow-up points (P < .0001); however, self-reported hip function did not improve between 6 and 24 months after arthroscopic surgery (P ≥ .11). Post hoc independent t tests indicated that women reported poorer hip function than did men before surgery (P ≤ .003) both on the HOS-ADL (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM], 67.4 ± 1.9 [men] vs 60.5 ± 1.3 [women]) and iHOT-33 (mean ± SEM, 38.0 ± 1.9 [men] vs 30.9 ± 1.3 [women]); scores were not different between sexes at any other time point.

Conclusion

These findings indicate improvements in self-reported hip function in patients with FAI, regardless of sex, until 6 months after hip arthroscopic surgery. Although women reported poorer preoperative function than did men, the differences were not significant 2 years after surgery.

Keywords: femoroacetabular impingement, hip arthroscopic surgery, hip function

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is an abnormal hip morphological condition that causes significant disability in young adults as early as the second decade of life.3 Surgical management of this condition is often undertaken via hip arthroscopic surgery, which restores bony congruence and improves function in the majority of patients.6,11,15 Hip arthroscopic surgery for carefully selected surgical candidates can promote not only a high rate of return to the previous level of activity2,19,21 but high patient satisfaction.1 However, more recent literature indicates that certain subgroups of patients, particularly women,12,15,20 may be at an increased risk for poorer outcomes after surgery.

Recent prospective studies show that women report significantly worse functional outcomes before and after hip arthroscopic surgery compared with men.15,20 Adolescent women demonstrated a higher rate of second hip arthroscopic procedures when followed up to 5 years after the index procedure,20 and female sex has been identified as a predictor of a longer than average recovery time from hip arthroscopic surgery.12 Differences in hip morphology, soft tissue laxity, muscle mass, and dynamic joint stabilization have been proposed as causes of the reported outcome differences between men and women with nonarthritic hip pain.9 Comparisons of sex-specific outcomes in this clinical population have been limited to a retrospective design12 or a single follow-up session.15,20 The addition of a large, prospective, longitudinal outcome study would fill a critical gap in understanding whether men and women undergoing hip arthroscopic surgery for FAI recover differently over time.

Subjective reports of health and hip function in patients with symptomatic FAI have often been quantified using outcome measures such as the modified Harris Hip Score and Hip Outcome Score (HOS). These measures have historically focused on older arthritic patients and are limited in their widespread use, having demonstrated a ceiling effect with the young and more active population.3,22 Another measure, the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33), was recently developed to assess hip-specific function in active young adults.8,10,13,17 The iHOT-33 is reliable and valid in this population and does not appear to have the ceiling effect identified in other commonly used outcome tools.17

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify whether self-reported hip function differed between men and women undergoing hip arthroscopic surgery for symptomatic FAI. We hypothesized that mean self-reported hip function scores would improve after arthroscopic surgery but that women would report poorer function than men both before and up to 2 years after arthroscopic surgery.

METHODS

Participants

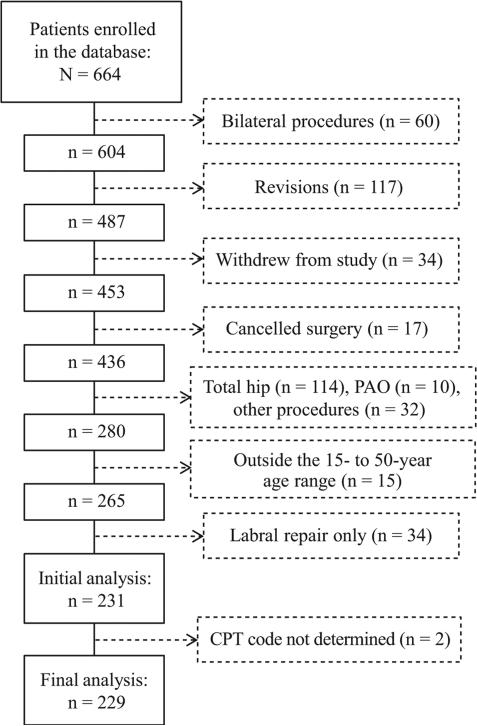

A total of 664 eligible patients were recruited during their initial visit with a single orthopaedic surgeon between November 2011 and June 2014. Surgical eligibility was determined by several clinical and radiographic guidelines: (1) clinical presentation consistent with FAI that adversely affected patient function, (2) alpha angle >50° for cam impingement or presence of acetabular retroversion and/or coxa profunda for pincer impingement, (3) failed nonoperative therapy, (4) hip pain relieved after an injection with a local anesthetic, and (5) minimal degenerative hip changes (Tönnis grade ≤1). Patients were excluded from the current study if they had undergone bilateral procedures (n = 60), had undergone previous hip surgeries (n = 117), or withdrew from the study (n = 34). Additional exclusion criteria were cancellation of surgery (n = 17), surgeries for conditions not classified as FAI (n = 190), and being outside of the 15- to 50-year age range (n = 15) (Figure 1). The study was approved by an institutional review board, and all participants provided informed consent when applicable before enrollment.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram. CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; PAO, periacetabular osteotomy.

Procedures

Self-reported hip function and demographic data were prospectively collected preoperatively at the time of the surgical consent visit and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after arthroscopic surgery. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University.7 REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies and provides (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.7 Self-reported hip function data were collected using the iHOT-3317 and the Hip Outcome Score activities of daily living subscale (HOS-ADL).16

Power and Statistical Analyses

A sample size of 92 (26 men and 66 women) was calculated based on an a level of .05, power of 80%, and effect size of 0.65, which was derived from the differences in self-reported function between adolescent male and female patients after hip arthroscopic surgery.20 Self-reported hip function data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for men and women separately at each time point. A linear mixed model for repeated measures was used to test differences in self-reported hip function over the study period using all available data points from the 229 enrolled patients. Sex and its interaction with time points were included as covariates in the model. The difference between men and women at each time point and the difference in changes between 2 time points were tested based on the corresponding contrasts of the parameters estimated in the mixed model. Missing data were handled by the mixed model based on the missing-at-random assumption. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted based on the completed data for each hypothesis tested using 2-sample t tests to confirm that the conclusions from the mixed model were robust to the model assumptions.

RESULTS

Women represented more than two-thirds (156/229, 68.1%) of the cohort at each time point and were of similar age (mean ± SD, 31.6 ± 10.8 [women] vs 31.1 ± 10.1 years [men]; P = .73) and body mass index (mean ± SD, 26.8 ± 11.9 [women] vs 27.5 ± 5.2 kg/m2 [men]; P = .76) to men at enrollment (Table 1). Women represented the highest percentage of all osteoplasties; none of the women underwent isolated chondroplasty (Table 2). There were no significant time × sex interactions for either the HOS-ADL (P = .12) or iHOT-33 (P = .64). There was a significant main effect of time for both measures (P < .0001), indicating that mean self-reported hip function scores improved over time for both men and women at a similar rate.

TABLE 1.

Sex Distribution of Patients at Each Study Time Point

| Before Arthroscopic Surgery (n = 229) | After Arthroscopic Surgery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mo (n = 180) | 6 mo (n = 170) | 12 mo (n = 148) | 24 mo (n = 64) | ||

| Women, n (%) | 156 (68.1) | 127 (70.6) | 124 (72.9) | 102 (68.9) | 45 (70.3) |

| Men, n (%) | 73 (31.9) | 53 (29.4) | 46 (27.1) | 46 (31.1) | 19 (29.7) |

TABLE 2.

Sex Distribution by Surgical Procedurea

| Surgical Procedure (CPT Code) | Men, n (%) | Women, n (%) | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral osteoplasty (29914) | 7 (21.2) | 26 (78.8) | 33 |

| Acetabular osteoplasty (29915) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 |

| Combined osteoplasty (29914, 29915) | 26 (36.1) | 46 (63.9) | 72 |

| Combined osteoplasty with labral repair (29914, 29915, 29916) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 8 |

| Femoral osteoplasty with labral repair (29914, 29916) | 32 (29.9) | 75 (70.1) | 107 |

| Acetabular osteoplasty with labral repair (29915, 29916) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 |

| Chondroplasty (29862) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 |

CPT, Current Procedural Terminology.

The HOS-ADL and iHOT-33 scores improved significantly between the preoperative time point (n = 229) and the 3-month (n = 180), 6-month (n = 170), 12-month (n = 148), and 24-month (n = 64) time points (P < .0001) (Table 3). There were no significant improvements in self-reported function from 6 to 24 months after arthroscopic surgery (P ≥ .11).

TABLE 3.

Changes in HOS-ADL and iHOT-33 Scores Between Each Study Time Pointa

| HOS-ADL |

iHOT-33 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | P Value | Men | Women | P Value | |

| Before arthroscopic surgery (reference) | ||||||

| 3 mo | 14.1 ± 2.1 | 21.4 ± 1.4 | <.0001 | 27.3 ± 2.9 | 33.1 ± 1.9 | < .0001 |

| 6 mo | 19.3 ± 2.2 | 24.1 ± 1.4 | <.0001 | 32.3 ± 3.3 | 37.4 ± 2.1 | < .0001 |

| 12 mo | 21.7 ± 2.1 | 25.7 ± 1.4 | <.0001 | 36.3 ± 3.3 | 37.9 ± 2.2 | < .0001 |

| 24 mo | 20.8 ± 2.7 | 25.7 ± 1.8 | <.0001 | 34.7 ± 4.0 | 34.2 ± 2.6 | < .0001 |

| 3 mo (reference) | ||||||

| 6 mo | 5.2 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 1.4 | ≤.004 | 5.0 ± 2.7 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | .07, .01b |

| 12 mo | 7.7 ± 1.8 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | ≤.003 | 9.0 ± 3.1 | 4.8 ± 2.0 | ≤.02 |

| 24 mo | 6.7 ± 2.7 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | ≤.017 | 7.4 ± 4.4 | 1.1 ± 2.9 | ≥.09 |

| 6 mo (reference) | ||||||

| 12 mo | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | ≥.16 | 4.0 ± 3.0 | 0.5 ± 1.9 | ≥.19 |

| 24 mo | 1.4 ± 2.7 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | ≥.39 | 2.4 ± 4.5 | −3.2 ± 2.9 | ≥.26 |

| 12 mo (reference) | ||||||

| 24 mo | 1.0 ± 2.3 | 0.0 ± 1.5 | ≥.66 | −1.6 ± 3.7 | −3.7 ± 2.3 | ≥.11 |

Results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Bolded values indicate a statistically significant difference compared with reference category (P < .05). HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Score activities of daily living subscale; iHOT-33, International Hip Outcome Tool.

P values on the iHOT-33 for men and women, respectively.

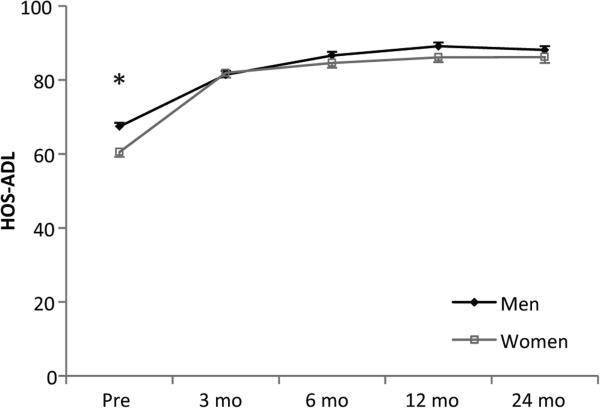

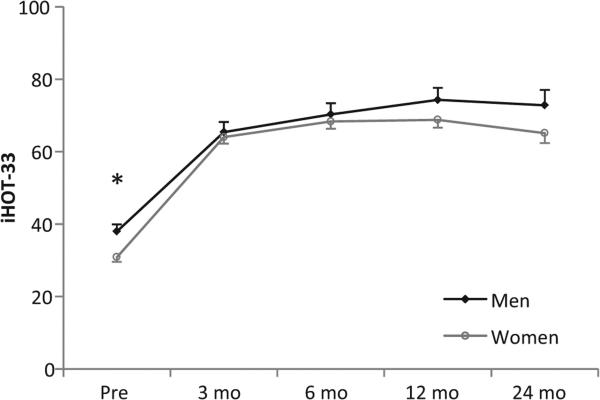

The main effect of sex was not statistically significant for either outcome measure (HOS-ADL: P = .14; iHOT-33: P = .07). However, post hoc t tests showed that women reported poorer hip function than men before surgery (P ≤ .003) both on the HOS-ADL (mean ± SEM: 67.4 ± 1.9 [men] vs 60.5 ± 1.3 [women]) (Figure 2) and iHOT-33 (mean ± SEM: 38.0 ± 1.9 [men] vs 30.9 ± 1.3 [women]) (Figure 3). Neither the HOS-ADL (P ≥ .2) nor the iHOT-33 (P ≥ .13) scores were different between men and women at any other time point.

Figure 2.

Mean Hip Outcome Score activities of daily living subscale (HOS-ADL) outcomes by sex at each study time point. Whiskers represent SEM. *Significant differences between men and women (P ≤ .05). Pre, before arthroscopic surgery.

Figure 3.

Mean International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33) outcomes by sex at each study time point. Whiskers represent SEM. *Significant differences between men and women (P ≤ .05). Pre, before arthroscopic surgery.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to compare self-reported hip function in men and women undergoing hip arthroscopic surgery for symptomatic FAI. The hypothesis was that mean self-reported hip function scores would improve after arthroscopic surgery regardless of sex but that women would report poorer function than men both before and up to 2 years after arthroscopic surgery.

These data partially support the a priori hypotheses; improvements in function were identified over the study period. Women did report significantly poorer hip function than men before surgery; however, the differences in self-reported hip function between sexes did not persist after surgery.

Hip arthroscopic surgery is a viable and effective treatment option for patients with nonarthritic hip pain that is not amenable to nonoperative care.1,3,6,15,19-21 As hypothesized, self-reported hip function improved after arthroscopic surgery in this cohort of patients, but the lack of significant improvement in men and women more than 6 months after surgery was unexpected. The majority of current literature evaluating outcomes after arthroscopic surgery for FAI has focused on a single follow-up time point, ranging from several months1,6,11 to years11,15,19,20 after the procedure. In this study, no improvements in self-reported hip function were identified between follow-ups subsequent to the 6-month postoperative time point. The inclusion of 3- and 6-month time points revealed that the first 6 months after hip arthroscopic surgery represented the time of greatest improvement in hip function in this sample. Importantly, the mean scores on both the iHOT-33 and HOSADL never reached 90% during the study period, a goal that is commonly equated with successful restoration of function for many orthopaedic populations.

Female sex is a predictor of a longer than average recovery time after arthroscopic hip surgery for the treatment of common hip disorders.12,15,20 A large prospective cohort study of over 600 patients undergoing hip arthroscopic surgery for FAI showed that women reported lower quality of life than men both before and after arthroscopic surgery.15 Although women demonstrated a greater improvement in quality of life scores after surgery, the mean score was still significantly lower than that of men at 1 year after arthroscopic surgery.15 In a smaller prospective study of 60 active adolescents, female patients continued to report significantly poorer hip function than their male counterparts between 2 and 5 years after arthroscopic surgery.20 The data from our study support the preoperative findings of other studies showing inferior hip function in women with symptomatic FAI13,15 but do not corroborate the evidence that shows that women continue to report poorer function postoperatively.15,20 The contrast in study findings could be explained by the difference in outcome tools used to quantify self-reported functional limitations and the range in the time frame for follow-up. While the current study standardized the time for each follow-up data collection, the studies by Malviya and colleagues15 and Philippon and colleagues20 included participants ranging from 1 to 7 years after hip arthroscopic surgery.

Sex-specific differences in the clinical and morphological presentation of symptomatic FAI have been identified before surgical intervention4,9,18 and may negatively influence postoperative outcomes. Women comprised more than two-thirds of this study's cohort, and with the exception of isolated chondroplasty, women also represented a majority of each of the surgical procedures studied. Although the focus of this study was not to evaluate whether specific morphological characteristics and pathological abnormalities influenced the differences in self-reported function between men and women over time, its potential effect cannot be overlooked. The small number of patients undergoing certain surgical procedures in this cohort limits quantification of the effect. Importantly, self-reported hip function may also be related to other measures of physical impairments and performance deficits (ie, strength, range of motion, biomechanical adaptations) in this clinical population, none of which were collected in this study. Distinguishing the subgroups of patients who are more or less likely to improve after hip arthroscopic surgery will facilitate evidence-based clinical decision making and ultimately maximize outcomes in this population.

There were several limitations to this prospective cohort study. The findings from this study may not be generalizable to patients who have undergone a revision procedure or who have bilateral symptomatic FAI, as they were excluded from analysis. Generalized joint laxity, capsular laxity of the hip, muscle weakness, and other joint-specific impairments were also not controlled for in this study and could limit its generalizability to patients with profound physical impairments in the presence of symptomatic FAI. Finally, data on 2-year outcomes were included from all available participants but did not meet our a priori sample size calculations, and thus, we could have been under-powered to detect sex-specific differences at this time point. Although the mean difference in iHOT-33 scores between men and women at 2 years after surgery (7.7) was comparable with the mean difference between sexes before surgery (7.1), the comparison did not reach statistical significance. Importantly, the mean difference between sexes at both time points exceeded the minimal clinically important difference of the iHOT-33 score (6.1) reported in the literature.17

The findings from this study indicate that despite poorer preoperative hip function, women with symptomatic FAI may achieve a similar level of function after arthroscopic surgery. The plateau in functional improvement more than 6 months after hip arthroscopic surgery highlights the need to investigate other factors that may mitigate progress toward full recovery. Currently accepted rehabilitation guidelines advocate for several months of structured rehabilitation phases, focusing on early protection of the healing joint, muscle strength, endurance and neuromuscular control, and eventual reintegration into prior activities.5,14 The findings of this study should both inform patient expectations for recovery and encourage future evaluations of other prognostic factors of successful functional outcomes after arthroscopic surgery for FAI.

CONCLUSION

FAI is a cause of significant disability in men and women, often beginning in adolescence and young adulthood. Although women with symptomatic FAI may report poorer function before surgery, hip arthroscopic surgery yields meaningful improvements in hip function in the majority of patients, regardless of sex.

Acknowledgments

source of funding: The authors acknowledge funding for the software support services used in this study from Stryker Orthopaedics and The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 8UL1TR000090-05).

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Alradwan H, Philippon MJ, Farrokhyar F, et al. Return to preinjury activity levels after surgical management of femoroacetabular impingement in athletes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1567–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunner A, Horisberger M, Herzog RF. Sports and recreation activity of patients with femoroacetabular impingement before and after arthroscopic osteoplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:917–922. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd T, Jones KS. Arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:7–13. doi: 10.1177/0363546511404144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz-Ledezma C, Lichstein PM, Maltenfort M, Restrepo C, Parvizi J. Pattern of impact of femoroacetabular impingement upon quality of life: the determinant role of extra-articular factors. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2323–2330. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0359-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelstein J, Ranawat A, Enseki KR. Post-operative guidelines following hip arthroscopy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s12178-011-9107-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabricant PD, Heyworth BE, Kelly BT. Hip arthroscopy improves symptoms associated with FAI in selected adolescent athletes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:261–269. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris-Hayes M, McDonough CM, Leunig M, et al. Clinical outcomes assessment in clinical trials to assess treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: use of patient-reported outcome measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(suppl 1):S39–S46. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hetsroni I, Dela Torre K, Duke G, Lyman S, Kelly BT. Sex differences of hip morphology in young adults with hip pain and labral tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinman RS, Dobson F, Takla A, O'Donnell J, Bennell KL. Which is the most useful patient-reported outcome in femoroacetabular impingement? Test-retest reliability of six questionnaires. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:458–463. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson CM, Giveans RM. Arthroscopic management of femoroace-tabular impingement: early outcomes measures. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HH, Klika AK, Bershadsky B, Krebs VE, Barsoum WK. Factors affecting recovery after arthroscopic labral debridement of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lodhia P, Slobogean GP, Noonan VK, Gilbert MK. Patient-reported outcome instruments for femoroacetabular impingement and labral pathology: a systematic review of the clinimetric evidence. Arthros-copy. 2011;27:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malloy P, Malloy M, Draovitch P. Guidelines and pitfalls for the rehabilitation following hip arthroscopy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s12178-013-9176-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malviya A, Stafford GH, Villar RN. Impact of arthroscopy of the hip for femoroacetabular impingement on quality of life at a mean follow-up of 3.2 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:466–470. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B4.28023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin RL, Philippon MJ. Evidence of reliability and responsiveness for the Hip Outcome Score. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohtadi NG, Griffin DR, Pedersen ME, et al. The development and validation of a self administered quality-of-life outcome measure for young, active patients with symptomatic hip disease: the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33). Arthroscopy. 2012;28:595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nepple JJ, Riggs CN, Ross JR, Clohisy JC. Clinical presentation and disease characteristics of femoroacetabular impingement are sex dependent. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:1683–1689. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philippon MJ, Briggs KK, Yen YM, Kuppersmith DA. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement with associated chondrolabral dysfunction: minimum two year follow up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:16–23. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philippon MJ, Ejnisman L, Ellis HB, Briggs KK. Outcomes 2 and 5 years following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in the patient aged 11 to 16 years. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1255–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philippon MJ, Schenker M, Briggs K, Kuppersmith D. Femoroacetabular impingement in 45 professional athletes: associated pathologies and return to sport following arthroscopic decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:908–914. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0332-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wamper KE, Sierevelt IN, Poolman RW, Bhandari M, Haverkamp D. The Harris Hip Score: do ceiling effects limit its usefulness in orthopedics. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:703–707. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.537808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]