Abstract

Lung infections with Mycobacterium abscessus, a species of multidrug resistant nontuberculous mycobacteria, are emerging as an important global threat to individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) where they accelerate inflammatory lung damage leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Previously, M. abscessus was thought to be independently acquired by susceptible individuals from the environment. However, using whole genome analysis of a global collection of clinical isolates, we show that the majority of M. abscessus infections are acquired through transmission, potentially via fomites and aerosols, of recently emerged dominant circulating clones that have spread globally. We demonstrate that these clones are associated with worse clinical outcomes, show increased virulence in cell-based and mouse infection models, and thus represent an urgent international infection challenge.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM; referring to mycobacterial species other than M. tuberculosis complex and M. leprae) are ubiquitous environmental organisms that can cause chronic pulmonary infections in susceptible individuals [1, 2], particularly those with pre-existing inflammatory lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) [3]. The major NTM infecting CF individuals around the world is Mycobacterium abscessus; a rapidly growing, intrinsically multidrug-resistant species, which can be impossible to treat despite prolonged combination antibiotic therapy [1, 3–5], leads to accelerated decline in lung function [6,7], and remains a contraindication to lung transplantation in many centers [3,8,9].

Until recently, NTM infections were thought to be independently acquired by individuals through exposure to soil or water [10–12]. As expected, previous analyses from the 1990s and 2000s [13–16] showed that CF patients were infected with unique, genetically diverse strains of M. abscessus, presumably from environmental sources. We used whole genome sequencing at a single UK CF center and identified two clusters of patients (11 individuals in total) infected with identical or near-identical M. abscessus isolates, which social network analysis suggested were acquired within hospital via indirect transmission between patients [17]; a possibility further supported by genomic sequencing [18] of a separate M. abscessus outbreak in a Seattle CF center [19].

Given the increasing incidence of M. abscessus infections in CF and non-CF populations reported globally [3, 20, 21], we investigated whether cross-infection, rather than independent environmental acquisition, might be the major source of infection for this organism and therefore undertook population-level, multinational, whole genome sequencing of M. abscessus isolates from infected CF patients, correlating results with clinical metadata and phenotypic functional analysis of isolates.

We generated whole genome sequences for 1080 clinical isolates of M. abscessus from 517 patients, obtained from UK CF clinics and their associated regional reference laboratories, as well as CF Centres in the US (UNC Chapel Hill), the Republic of Ireland (Dublin), mainland Europe (Denmark, Sweden, The Netherlands), and Australia (Queensland). We identified 730 isolates as M. a. abscessus, 256 isolates as M. a. massiliense, 91 isolates as M. a. bolletii, with three isolates (from 3 different patients) containing more than one subspecies.

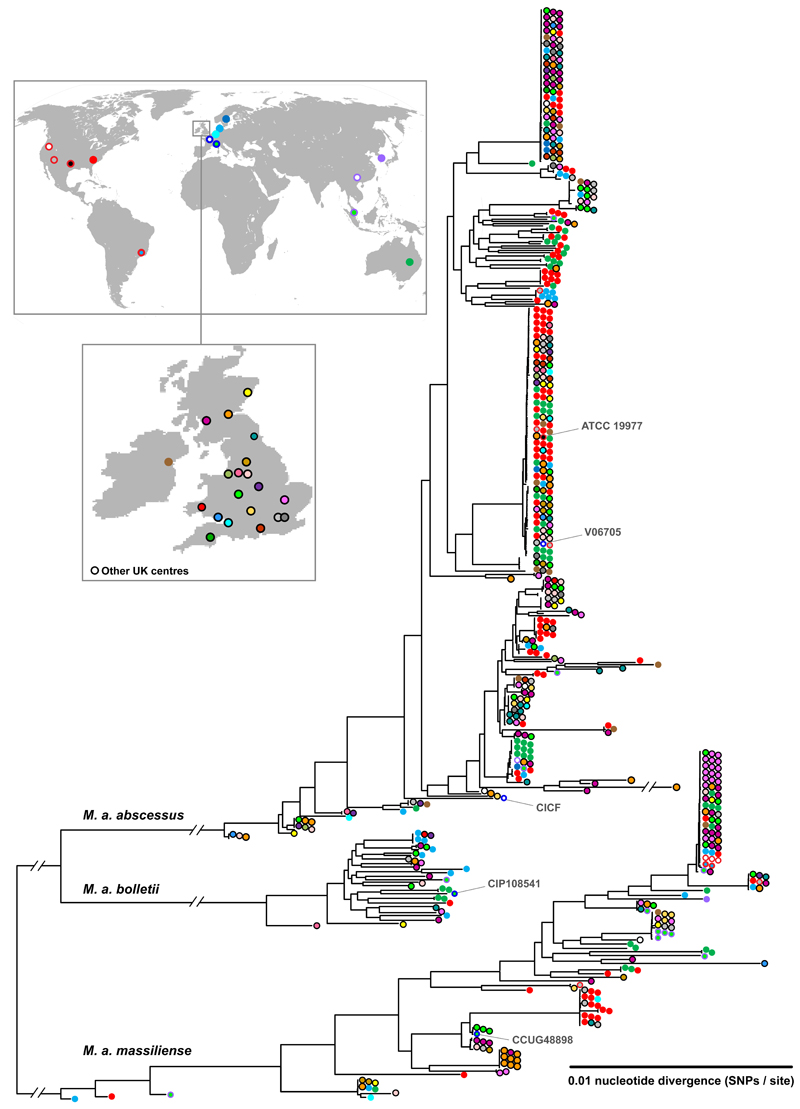

Phylogenetic analysis of these sequences (using one isolate per patient), supplemented by published genomes from US, France, Brazil, Malaysia, China, and South Korea (Table S1), was performed and analysed in the context of the geographical provenance of isolates (Figure 1; Figure S1). As done previously [17], we obtained maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees demonstrating separation of M. abscessus into three clearly divergent subspecies (M. a. abscessus, M. a. bolletii, and M. a. massiliense), challenging recent reclassifications of M. abscessus into only two subspecies [22].

Figure 1. Global phylogeny of clinical isolates of M. abscessus.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of clinical isolates of M. abscessus collected with relevant local and/or national Ethical Board approval from 517 patients (using one isolate per patient), obtained from UK CF clinics and their associated regional reference laboratories, CF Centres in the US (UNC Chapel Hill), the Republic of Ireland (Dublin), mainland Europe (Denmark, Sweden, The Netherlands), and Australia (Queensland), supplemented by published genomes from US, France, Brazil, Malaysia, China, and South Korea (listed in Table S1).

Within each subspecies, we found multiple examples of deep branches (indicating large genetic differences) between isolates from different individuals, consistent with independent acquisition of unrelated environmental bacteria. However, we also identified multiple clades of near-identical isolates from geographically diverse locations (Figure 1), suggesting widespread transmission of circulating clones within the global CF patient community.

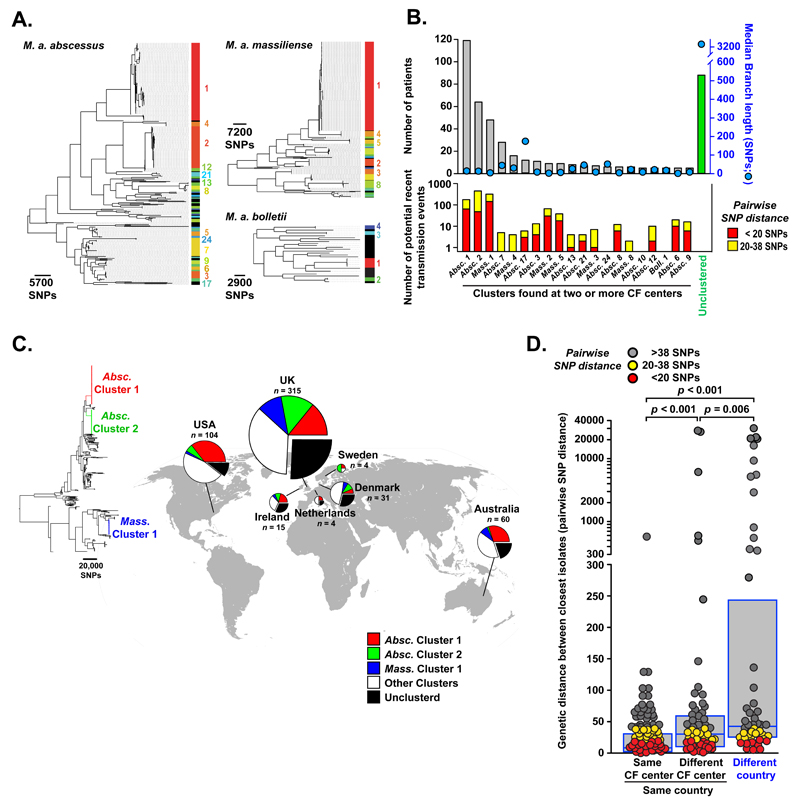

To investigate further the relatedness of isolates from different individuals, we analysed each subspecies phylogeny for the presence of high density phylogenetic clusters (see Supplementary Methods [23]). We identified multiple dense clusters of isolates, predominantly within the M. a. abscessus and M. a. massiliense subspecies (Figure 2A), indicating the presence of dominant circulating clones. We next excluded clusters found in only one CF centre from further analysis to remove related isolates that might have been acquired from a local environmental point source. We found that most patients (74%) were infected with clustered, rather than unclustered, isolates, principally from M. a. abscessus Cluster 1 and 2, and M. a. massiliense Cluster 1 (Figure 2B). The median branch lengths of almost all clusters found in two or more CF centers was less than 20 SNPs (range 1-175 SNPs), indicating a high frequency of identical or near identical isolates infecting geographically separate individuals.

Figure 2. Transcontinental spread of dominant circulating clones.

(A). Hierarchical branch density analysis of phylogenetic trees for each subspecies of M. abscessus identifies multiple clusters of closely related isolates predominantly within the M. a. abscessus and M. a. massiliense subspecies (numbered, and spectrally coloured red to blue, from most densely clustered to least; black indicating no significant clustering). (B). Analysis of M. abscessus clusters found in two or more CF centers showing (top) numbers of patients infected with each cluster (grey bars) or unclustered isolates (green) and median branch length (SNPs) of different patients’ isolates within each cluster (blue circles); (bottom) numbers of potential recent transmission events with < 20 SNPs (red) or 20 - 38 SNPs (yellow) difference between isolates from different patients. (C) Global distribution of clustered M. abscessus isolates showing M. a. abscessus Cluster 1 (red) and Cluster 2 (green), M. a. massiliense Cluster 1 (blue), other clustered isolates (grouped together for clarity; white) and unclustered isolates (black) with numbers of patients (n) sampled per location. (D) Genetic differences between isolates (measured by pairwise SNP distance) from different patients attending the same CF center, different CF centers within the same country, or CF centers in different countries (boxes indicate median and interquartile range; p values obtained from Mann Whitney Rank Sum tests). To exclude multiple highly distant comparisons, for each isolate only the smallest pairwise distance with an isolate from another patient is included. Colour coding indicates whether there were < 20 SNPs difference (red), 20-38 SNPs difference (yellow), or >38 SNPs difference (grey) between isolates from different patients.

To determine how much of the genetic relatedness found within clusters was attributable to recent transmission, we first examined the within-patient genetic diversity of M. abscessus isolates from single individuals. In keeping with our previously published results [17], we found that 90% of same-patient isolates differed by less than 20 SNPs, while 99% of same-patient isolates differed by less than 38 SNPs (Figure S2). We therefore classified isolates from different individuals varying by less than 20 SNPs as indicating ‘probable’, and those varying by 20-38 SNPs as indicating ‘possible’, recent transmission (whether direct or indirect). We thereby identified multiple likely recent transmission chains in virtually all multi-site clusters of M. abscessus (Figure 2B), and across the majority of CF centers (Figure S3).

We next examined the global distribution of clustered isolates and found that, in all countries, the majority of patients were infected with clustered rather than unclustered isolates (Figure 2C; Table S2), suggesting frequent and widespread infection of patients with closely related isolates. Moreover, the three dominant circulating clones, M. a. abscessus Clusters 1 and 2, and M. a. massiliense Cluster 1, were all represented in the USA, European, and Australian collections of clinical isolates, indicating trans-continental dissemination of these clades.

We then compared the genetic differences between isolates (measured by pairwise SNP distance) as a function of geography. As expected from our previous detection of hospital-based transmission of M. abscessus [17], average genetic distances were significantly shorter for M. abscessus isolates from the same CF center than those from different CF centers within the same country or from different countries (Figure 2D). However, we also detected numerous examples of identical or near-identical isolates infecting groups of patients in different CF centers and, indeed, across different countries (Figure 2D), indicating the recent global spread of M. abscessus clones throughout the international CF patient community.

We applied Bayesian analysis [24] to date the establishment and spread of dominant circulating clones (Figure S4, S5), focusing on M. a. massiliense Cluster 1, which includes isolates from both the Seattle [19] and Papworth [17] CF Center outbreaks, as well as isolates from CF centres across England (Birmingham, London, Leicester), Scotland (Lothian, Glasgow), Ireland (Dublin), Denmark (Copenhagen), Australia (Queensland), and the USA (Chapel Hill, NC) (Figure 3A). We estimate that the most recent common ancestor of isolates infecting patients from all these locations emerged around 1978 (95% CI: 1955-1995), clearly indicating recent global dissemination of this dominant circulating clone amongst individuals with CF (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Dating the emergence of dominant circulating clones.

(A). Dating the emergence of the M. a. massiliense Cluster 1 (responsible for the Papworth and Seattle CF center outbreaks), using Bayesian analysis, with geographical annotation of isolates within the cluster. (B). Predicted evolution of subclones (identified through minority variant linkage; see Supplementary Methods [23]) within a single patient with CF (Patient 2 from Ref. 19) chronically infected with the dominant circulating clone Massiliense Cluster 1 (representative of a total of 11 patients studied). (i) Analysis revealed successive acquisition of non-synonymous polymorphisms (NS) by the most common recent ancestral clone (MRCA; white) in potential virulence genes (UBiA, MAB_0173; Crp/Fnr, MAB_0416c; mmpS, MAB_0477; PhoR, MAB_0674) and then transmission of a single subclone to another patient from the same CF center (Patient 28 from Ref. 19). (ii) Frequency of each subclone within longitudinal sputum isolates analysed during the course of Patient 2’s infection and the subsequent transmission of a subclone to Patient 28. We observed considerable heterogeneity in the detected repertoire of subclones within each sputum sample (vertical rectangles coloured to illustrate the proportion of detected subclones coded as for (i) in each sputum sample), reflecting either temporal fluctuations in dominant sub-lineages or variable sampling of geographical diversity of subclones within the lung (as previously described for P. aeruginosa [37]). Previously determined opportunities for hospital-based cross-infection between the two patients (using social network and epidemiologic analysis [17]), are shown in grey vertical bars.

Furthermore we were able to resolve individual transmission events between patients infected with dominant circulating clones through two orthogonal approaches. Firstly, using high-depth genomic sequencing of colony sweeps, we were able to track changes in within-patient bacterial diversity in sputum cultures of a single individual over time. By linking the frequency of occurrence of minority variants in longitudinal samples, we were able to define the presence of particular subclones within infected individuals, assign their likely evolutionary development (involving the successive acquisition of non-synonymous mutations in likely virulence genes; Figure 3B), monitor their relative frequencies over time, and demonstrate their transmission between patients (Figure 3B). Secondly, through longitudinal whole genome sequencing of isolates collected over time from individuals, we were able to find multiple examples of the complete nesting of one patient’s sampled diversity within another’s (Figure S6). Such paraphyletic relationships are strongly indicative of recent person-to-person transmission [25].

We next examined potential mechanisms of transmission of M. abscessus between individuals (which our previous epidemiological analysis had suggested was indirect rather than via direct contact between patients [17]). We provide proof of concept for fomite spread of M. abscessus (detecting three separate transmission events associated with surface contamination of an inpatient room by an individual infected with a dominant circulating clone; Figure S7), and also for potential airborne transmission (by experimentally demonstrating the generation of long-lived, potentially infectious cough aerosols by an infected CF patient; Figure S8).

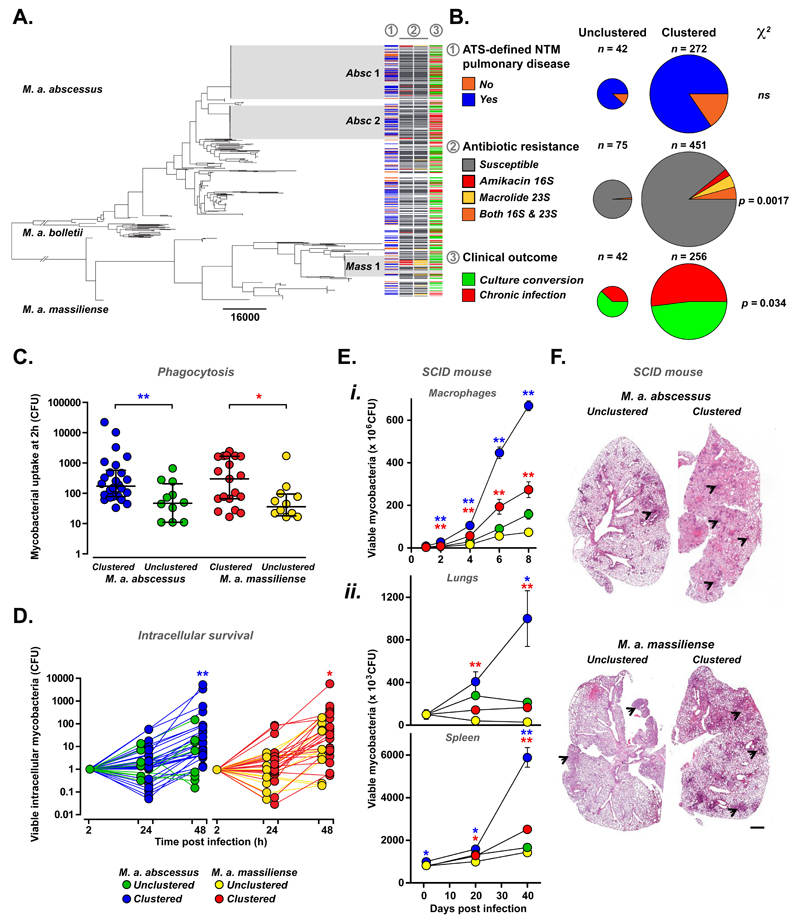

A potential explanation for the emergence of dominant clones of M. abscessus is that they are more efficient at infection and/or transmission. We therefore analysed clinical metadata to establish whether outcomes were different for patients infected with clustered rather than unclustered isolates. We correlated clinical outcomes with bacterial phylogeny and the presence of constitutive resistance to two key NTM antibiotics, amikacin and macrolides [26, 27], acquired through point mutations in the 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA respectively (Figure 4A). We found no differences in the proportions of M. abscessus-positive individuals diagnosed with ATS-defined NTM pulmonary disease [1], (namely the presence of two or more culture-positive sputum samples with NTM-associated symptoms and radiological changes), but did observe increased rates of chronic infection in individuals infected with clustered rather than unclustered isolates (Figure 4B). As anticipated for transmissible clones exposed to multiple rounds of antibiotic therapy, we also found high rates of constitutive amikacin and/or macrolide resistance in clustered isolates (Figure 4B). Of note, resistance to these two antibiotics did not necessarily result in a poor clinical outcomes (Figure S9), suggesting that additional bacterial factors might contribute to worse responses in patients infected with clustered isolates.

Figure 4. Comparison of clinical outcomes and functional phenotyping of clustered and unclustered M. abscessus isolates.

(A, B). Relationship of phylogeny with clinical metadata. Phylogenetic tree of M. abscessus isolates (one isolate per patient) with dominant circulating clones M. a. abscessus 1 (Absc 1), abscessus 2 (Absc 2), and M. a. massiliense (Mass 1) highlighted (grey). For each isolate, clinical data (where available) was used to determine whether (column 1) the infected patient fulfilled the ATS/IDSA criteria for NTM pulmonary disease, namely the presence of two or more culture-positive sputum samples with NTM-associated symptoms and radiological changes [1] (yes: blue; no: orange); whether (column 2) isolates have acquired amikacin resistance (through 16S rRNA mutations; red), macrolide resistance (through 23S rRNA mutations; yellow), or both (orange- B only); and whether (column 3) patients culture converted (green) or remained chronically infected (red) with M. abscessus. (C, D). In vitro phenotyping of representative isolates of clustered (blue) and unclustered (green) M. a. abscessus and clustered (red) and unclustered (yellow) M. a. massiliense comparing phagocytosis by (C) and intracellular survival (normalised for uptake) within (D) differentiated THP1 cells. Data points represent averages of at least three independent replicates. (E, F) Using SCID mice, infection with clustered M. a. abscessus (blue) and M. a. massiliense (red) led to (E) greater intracellular survival within (i) bone marrow-derived macrophages in vitro and (ii) higher bacterial burdens in lung and spleen after in vivo inoculation with 1 x 107 bacilli per animal with (F) worse granulomatous lung inflammation (arrowheads), than unclustered controls (M. a. abscessus green; M. a. massiliense yellow), scale bar x 4. CFU data is shown as mean ± sem; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test).

To explore differences in intrinsic virulence between clustered and unclustered M. abscessus, we subjected a panel of representative isolates (27 clustered and 17 unclustered M. a. abscessus; 25 clustered and 13 unclustered M. a. massiliense) to a series of in vitro phenotypic assays. While we found no or only minor differences between groups in their colony morphotype, biofilm formation, ability to trigger cytokine release from macrophages (Figure S10) and their overall phenotypic profile (by multifactorial analysis; Figure S11), we detected significantly increased phagocytic uptake (Figure 4C) and intracellular survival in macrophages (Figure 4D) of clustered isolates of both M. a. abscessus and M. a. massiliense compared to unclustered controls, indicating clear differences in pathogenic potential. Moreover, infection of SCID mice revealed significantly greater bacterial burden (Figure 4E) and granulomatous inflammation (Figure 4F) following inoculation with clustered rather than unclustered isolates of M. a. abscessus and M. a. massiliense, confirming differences in virulence between these groups.

In summary, our results reveal that the majority of M. abscessus infections of individuals with CF worldwide are caused by genetically-clustered isolates, suggesting recent transmission, rather than independent acquisition of genetically-unrelated environmental organisms. Given the widespread implementation of individual and cohort segregation of patients in CF centres in Europe [28], the USA [29], and Australia [30] (which have led to falling levels of MRSA, Burkholderia, and transmissible Pseudomonas infections [31–33]), we believe that the likely mechanism of local spread of M. abscessus is via fomite spread or potentially through the generation of long-lived infectious aerosols (as identified for other CF pathogens [34–36]). Although further research is needed, both transmission routes are plausible given our findings (Figures S7, S8), and would be potentially enhanced by the intrinsic desiccation resistance of M. abscessus. Such indirect transmission, involving environmental contamination by patients, is supported by our previous social network analysis of a UK outbreak of M. abscessus [17] in CF patients, which revealed hospital-based cross-infection without direct person-to-person contact, and by the termination of a Seattle M. abscessus outbreak associated with the introduction of clinic room negative pressure ventilation and double room cleaning [19]. The long-distance spread of circulating clones is more difficult to explain. Importantly we found no evidence of CF patients or of equipment moving between CF centers in different countries indicating that the global spread of M. abscessus may be driven by alternative human, zoonotic or environmental vectors of transmission.

Our study illustrates the power of population-level genomics to uncover modes of transmission of emerging pathogens and has revealed the recent emergence of global dominant circulating clones of M. abscessus that have spread between continents. These clones are better able to survive within macrophages, cause more virulent infection in mice, and are associated with worse clinical outcomes, suggesting that the establishment of transmission chains may have permitted multiple rounds of within-host genetic adaptation to allow M. abscessus to evolve from an environmental organism to a true lung pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Materials and Methods

Supplementary References (38-58)

Figs. S1 to S12

Tables S1, S2

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust grant 098051 (JMB, SH, JP) and 107032AIA (RAF, DMG), The Medical Research Council (JMB), The UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust (DMG, DR-R, IE, JP, RAF), Papworth Hospital (DMG, KPB, CSH, RAF), NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (RAF), NIHR Specialist Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit, Imperial College London (DB), The UKCRC Translational Infection Research Initiative (JP), CF Foundation Therapeutics grant (SB, TK, CW, LM, PS), the Australian NHMRC (LK) and The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation (SB, TK, CC, RT, LK, LM, GJ), and National Services Division, NHS Scotland (IL) We are grateful to the following for their assistance with microbiological culture, environmental sampling, and isolate retrieval: Kate Ball (Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust); Malcolm Brodlie and Matt Thomas (Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK); Grace Smith (Regional Mycobacterial Reference Laboratory, Birmingham, UK); Patricia Fenton & Keith Thickett (Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK); Rhian Williams (Wales Centre for Mycobacteria, UK); Vasanthini Athithan and Margaret Gillham (Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust). Jukka Corander (University of Oslo) assisted with BAPs clustering analysis. All sequence data associated with this study is deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession ERP001039. Ethical approval for the study was obtained nationally for centres in England and Wales from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES; REC reference: 12/EE/0158) and the National Information Governance Board (NIGB; ECC 3-03 (f)/2012), for Scottish centres from NHS Scotland Multiple Board Caldicott Guardian Approval (NHS Tayside AR/SW), and locally for other centres. Aerosol studies were approved by The Children’s Health Queensland HHS Human Research Ethics Committee HREC/14/QRCH/88 and TPCH Research Governance Office SSA/14/QPCH/202.

References

- 1.Griffith DE, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winthrop KL, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and clinical features: an emerging public health disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;82:977–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0503OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floto RA, et al. US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus recommendations for the management of nontuberculous mycobacteria in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2016;71(Suppl 1):i1–i22. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeon K, et al. Antibiotic treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus lung disease: a retrospective analysis of 65 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:896–902. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0704OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarand J, et al. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:565–71. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esther CR, Jr, et al. Chronic Mycobacterium abscessus infection and lung function decline in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esther CR, Jr, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:39–44. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanguinetti M, et al. Fatal pulmonary infection due to multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:816–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.816-819.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor JL, Palmer SM. Mycobacterium abscessus chest wall and pulmonary infection in a cystic fibrosis lung transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:985–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falkinham JO., 3rd Environmental sources of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Ingen J, et al. Environmental sources of rapid growing nontuberculous mycobacteria causing disease in humans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:888–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomson R, et al. Isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from household water and shower aerosols in patients with pulmonary disease caused by NTM. J Clin Microbiol. 51:3006–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00899-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivier KN, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. I: multicenter prevalence study in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:828–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-678OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sermet-Gaudelus I, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus and children with cystic fibrosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1587–91. doi: 10.3201/eid0912.020774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bange FC, et al. Lack of transmission of mycobacterium abscessus among patients with cystic fibrosis attending a single clinic. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1648–50. doi: 10.1086/320525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson BE, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium abscessus, with focus on cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1497–594. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02592-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant JM, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2013;381:1551–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60632-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tettelin H, et al. High-level relatedness among Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense strains from widely separated outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:364–71. doi: 10.3201/eid2003.131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aitken ML, et al. Respiratory outbreak of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense in a lung transplant and cystic fibrosis center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:231–2. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.185.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prevots DR, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:970–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierre-Audigier C, et al. Age-related prevalence and distribution of nontuberculous mycobacterial species among patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3467–70. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3467-3470.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leao SC, et al. Proposal that Mycobacterium massiliense and Mycobacterium bolletii be united and reclassified as Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii comb. nov., designation of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus subsp. nov. and emended description of Mycobacterium abscessus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61:2311–3. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.023770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Materials and methods are available as Supplementary Online Materials

- 24.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero-Sevenson EO, Bulla I, Leitner T. Phylogenetically resolving epidemiologic linkage. PNAS. 2016;113:2690–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522930113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prammananan T, et al. A single 16S ribosomal RNA substitution is responsible for resistance to amikacin and other 2-deoxystreptamine aminoglycosides in Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium chelonae. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1573–81. doi: 10.1086/515328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallace RJ, Jr, et al. Genetic basis for clarithromycin resistance among isolates of Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1676–81. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conway S, et al. European Cystic Fibrosis Society Standards of Care: Framework for the Cystic Fibrosis Centre. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(Suppl 1):S3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saiman L, et al. Infection prevention and control guideline for cystic fibrosis: 2013 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(Suppl 1):S1–67. doi: 10.1086/676882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell SC, Robinson PJ. Cystic Fibosis Standards of Care, Australia. 2008 https://www.rah.sa.gov.au/thoracic/whats_new/documents/CFA_Standards_of_Care_journal_31_Mar_08.pdf.

- 31.Doe SJ, et al. Patient segregation and aggressive antibiotic eradication therapy can control methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at large cystic fibrosis centres. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.France MW, et al. The changing epidemiology of Burkholderia species infection at an adult cystic fibrosis centre. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7:368–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones AM, et al. Prospective surveillance for Pseudomonas aeruginosa cross-infection at a cystic fibrosis center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:257–260. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-513OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wainwright CE, et al. Cough-generated aerosols of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria from patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2009;64:926–31. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knibbs LD, et al. Viability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cough aerosols generated by persons with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2014;69:740–5. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panagea S, et al. Environmental contamination with an epidemic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Liverpool cystic fibrosis centre, and study of its survival on dry surfaces. J Hosp Infect. 2005;59:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorth P, et al. Regional isolation drives bacterial diversification within Cystic Fibrosis Lungs. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18:307–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponstingl H. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute; Hinxton: 2012. SMALT. http://www.sanger.ac.uk/science/tools/smalt-0 accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ripoll F, et al. Non mycobacterial virulence genes in the genome of the emerging pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus. PloS one. 2009;4:e5660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris SR, et al. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science. 2010;327:469–474. doi: 10.1126/science.1182395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zerbino DR. Using the Velvet de novo assembler for short-read sequencing technologies. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2010;Chapter 11:Unit11.15. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1105s31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng L, Connor TR, Siren J, Aanensen DM, Corander J. Hierarchical and spatially explicit clustering of DNA sequences with BAPS software. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1224–1228. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris S. 2016 https://github.com/simonrharris/tree_gubbins.

- 47.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rambaut A, D AJ. Tracer v1.5. 2007 Available from http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer.

- 49.Firth C, et al. Using time-structured data to estimate evolutionary rates of double-stranded DNA viruses. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:2038–2051. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hepburn L, et al. Innate immunity. A Spaetzle-like role for nerve growth factor β in vertebrate immunity to Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2014;346:641–646. doi: 10.1126/science.1258705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schiebler M, et al. Functional drug screening reveals anticonvulsants as enhancers of mTOR-independent autophagic killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through inositol depletion. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:127–139. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software. 2008;25:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shang S, et al. Increased virulence of an epidemic strain of Mycobacterium massiliense in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ordway D, et al. Animal model of Mycobacterium abscessus lung infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1502–1511. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Obregón-Henao A, et al. Susceptibility of Mycobacterium abscessus to antimycobacterial drugs in preclinical models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:6904–6912. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00459-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ordway D, et al. Influence of Mycobacterium bovis BCG Vaccination on Cellular Immune Response of Guinea Pigs Challenged with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cellul Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1248–1258. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00019-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ordway D, et al. The hypervirulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain HN878 induces a potent TH1 response followed by rapid down-regulation. J Immunol. 2007;179:522–531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saito Y, et al. Characterization of endonuclease III (nth) and endonuclease VIII (nei) mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3783–3785. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3783-3785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.