Abstract

Objective To examine the need for, use of and satisfaction with information and support following primary treatment of breast cancer.

Design Cross‐sectional survey.

Participants Cohort of 266 surviving women diagnosed with breast cancer over a 25‐month period at a tertiary hospital, Adelaide, Australia. Time since diagnosis ranged from 6 to 30 months.

Main outcome measures Need for, use of and satisfaction with information and support.

Results Women reported high levels of need for information about a variety of issues following breast cancer treatment. Ninety‐four percentage reported a high level of need for information about one or more issues, particularly recognizing a recurrence, chances of cure and risk to family members of breast cancer. However, few women (2–32%) reported receiving such information. The most frequently used source of information was the surgeon followed by television, newspapers and books. The most frequently used source of support was family followed by friends and the surgeon. Few women (<7%) used formal support services or the Internet. Women were very satisfied with the information and support that they received from the surgeon and other health professionals but reported receiving decreasing amounts of information and support from them over time.

Conclusions Women experience a high need for information about breast cancer related issues following primary treatment of breast cancer. These needs remain largely unmet as few women receive information about issues that concern them. The role of the surgeon and other health professionals is critical in narrowing the gap between needing and receiving information.

Keywords: breast cancer, consumers, health care, information, support

Introduction

Following the primary treatment of breast cancer, women encounter a range of physical and psychosocial problems such as pain, lymphoedema, anger, depression, fear of recurrence and sexual difficulties. 1 , 2 Some quality of life issues such as arm pain, fear of recurrence, sexual difficulties and body image concerns persist or even worsen in the second and third years following treatment. 3 The provision of information and support to women with breast cancer about psychosocial and other survivorship issues can reduce anxiety, distress and uncertainty and improve quality of life. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Women with breast cancer express a high level of need for information and want to know as much as possible. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 When specific items of information are compared, women rate information about the likelihood of cure, spread of disease and treatment options as most important and information about sexuality as least important, both at the time and further from the time of diagnosis. 14 , 15 , 16

Women find information provided by doctors and nurses particularly helpful. 16 They also use a variety of other sources of information and support apart from health professionals. 17 Family and friends are frequently used as important sources of support, although information provided by family and friends is perceived to be less helpful. 18 , 19 , 20 Women also access information and support through formal support services (such as cancer telephone information services, volunteer peer support programmes, and breast cancer support groups) and the print and electronic media. 2 , 21

Health professionals consistently underestimate the amount of information desired by patients with cancer and often make inaccurate assumptions about the priority information needs of patients. 22 , 23 This is reflected in reports that many women are dissatisfied with the information that they receive following hospital discharge. 24 There are indications that the type of information and support that women desire may change with time following the diagnosis. 25 , 26 The amount of information and support received by women from family, friends and the surgeon decreases over the first few months following diagnosis and by 21 months after diagnosis women rate information from the media as useful as information from the specialist doctor. 15 , 18

Support is considered to be a multidimensional rather than a single construct. 27 It has been categorized into three dimensions: emotional, informational and instrumental. 28 Emotional support involves listening, reassuring and comforting, informational support involves using information to guide or advise while instrumental support involves providing practical assistance such as money, transport, childcare or home help. This study focuses on the provision of emotional (support) and informational support (information).

The study examines the needs and preferences for information and support of women between 6 months and two and a half years following the diagnosis of breast cancer and the ways in which women meet those needs. The objectives are to describe, the issues about which women want information and whether women received that information; the sources used for information and support and satisfaction with these sources; and changes in these factors with time since diagnosis.

Most published data about women's needs and preferences for information and support were collected at the time of diagnosis and in the following few months. There is less understanding of women's needs and preferences further from the time of diagnosis and in particular there continues to be uncertainty about how women's preferences and needs change over time. This study was designed to address these gaps using a representative cohort sample rather than either a convenience sample or a sample of consecutive clinic attendees.

Method

A cohort of women was surveyed by post in October 1999. The cohort comprised all 266 surviving women diagnosed with breast cancer at a major tertiary public hospital in Adelaide, Australia, during a 25‐month period between March 1997 and 1999. Women who were not aware of the diagnosis of breast cancer and women residing in nursing homes were excluded.

Adelaide is the capital and major urban centre of South Australia, one of six Australian states. In 1997 South Australia's population was 1 480 000 with around three quarters residing in Adelaide. There are three major public hospitals in Adelaide, which provide tertiary care to the entire population of South Australia. During 1997 and 1998 the number of South Australian women diagnosed with breast cancer in South Australia was 888 and 975, respectively. 29 , 30

At data collection, the time since diagnosis for respondents ranged from 6 to 30 months. Selection of time from diagnosis of at least 6 months ensured that respondents had completed primary treatment, while selection of time from diagnosis of no more than 30 months ensured that most respondents were routinely offered six monthly follow‐up. In addition this time period was chosen in order to collect a representative cohort of an adequate size without the need for expensive tracing procedures.

The survey consisted of 148 items (140 closed and eight open items) and was developed using a range of sources. These included interviews with women and service providers, a focus group with women with breast cancer, findings from a literature review and the report of Australia's first National Breast Cancer Conference for women. 15 , 21 , 31 Face validity of the questionnaire was explored using feedback from women and providers. This was followed by formal pilot testing on a random sample of 25 women diagnosed with breast cancer. The survey is available on request from the first author. Ethics approval was obtained from two local research ethics committees.

The survey included items about:

-

•

Perceived importance of receiving information about 13 issues relating to survival and to physical and psychosocial aspects of quality of life, and whether information had been received about each issue within the previous 6 months.

-

•

Current use of and satisfaction with 17 sources of information including family and friends, health professionals, print and electronic media, the Internet and formal support services.

-

•

Current use of and satisfaction with 12 sources of support including family and friends, health professionals, formal support services and the Internet.

Attitudinal variables were measured using an ordinal scale, in the form of a complete statement and a four point Likert response. Other variables, including demographic and treatment variables, were measured using a nominal scale.

Data were analysed using Stata release 5 and 6. 32 , 33 Variables measured on a four point Likert scale were collapsed into two categories. Responses in the ‘not’ or ‘slightly’ (important/useful/helpful) categories were combined and responses in the ‘moderately’ and ‘extremely’ (important/useful/helpful) categories were combined. Items were then ranked according to the percentage of women who rated a particular item in the moderately/extremely category. This method of analysis has been previously used to rank a variety of unmet needs of people living with cancer, including needs for information and support. 13 , 34 , 35

Bi‐variate analysis was undertaken to examine associations with age and time since diagnosis. Time since diagnosis was categorized into four groups (6–11, 12–17, 18–23 and 24–30 months). Age was categorized into three groups (under 50 years, 50–69 years and over 69 years) because 50–69‐year‐old women are targeted for early detection of breast cancer by mammographic screening in Australia. Time and age trends were analysed using the global chi‐squared (χ2) statistic (to examine the null hypothesis of homogeneity) and the Mantel test for trend of odds (to test for linear trend of responses over time). 36 We hypothesized that there was a decreasing linear trend of needing and of receiving information and support with increasing time from diagnosis.

Open‐ended items were analysed using content analysis as described by Berg 37 in order to identify prevailing themes about women's needor lack of need for information and support.

Results

Two hundred and seventeen women completed the survey with a response rate of 82%. Table 1 describes the demographic and treatment characteristics of respondents. The age of respondents ranged from 24 to 90 years with a mean of 58 years. Three quarters of respondents had completed secondary level of education or higher. Younger women (under 50 years) were more likely to have completed tertiary levels of education, χ2 = 6.6, P = 0.01, degrees of freedom (d.f.) = 1. One hundred and ninety‐six (90%) women lived in urban areas that were highly accessible to services according to the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia 38 while 21 (10%) women lived in rural areas that were less accessible to services. One hundred and thirty (60%) women were born in Australia and 52 (24%) in UK. The remaining 33 women were born in 20 different countries. Nearly all respondents (96%) had a regular general practitioner (GP) while almost a quarter (22%) of respondents had a first‐degree relative diagnosed with breast cancer.

Table 1.

Demographic and treatment characteristics of respondents

| Characteristic | N = 217* | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <50 years | 51 | 23 |

| 50–69 years | 128 | 59 | |

| >69 years | 38 | 18 | |

| Education completed | Primary | 33 | 15 |

| Secondary | 123 | 57 | |

| Tertiary | 60 | 28 | |

| Time since diagnosis | 6–11 months | 47 | 22 |

| 12–17 months | 57 | 26 | |

| 18–23 months | 47 | 22 | |

| 24–30 months | 56 | 30 | |

| Treatment | Surgery | 207 | 97 |

| Chemotherapy | 72 | 34 | |

| Radiotherapy | 131 | 62 | |

| Tamoxifen** | 133 | 62 | |

| Treatment completed** | 192 | 92 | |

| Other | 1° relative with breast cancer | 48 | 22 |

| Has a regular GP | 209 | 96 |

*Incomplete response in some categories.

* *Four (2%) women unsure.

There was no significant difference in the time since diagnosis among respondents and non‐respondents, although the mean age of respondents was 5 years younger than that of non‐respondents (t = 2.3, P = 0.03, d.f. = 56).

Information about specific issues

Two hundred and five (94%) women reported that it was moderately or extremely important to receive information about one or more of 13 specified issues while 210 (97%) women indicated that it was slightly, moderately or extremely important to receive information about one or more of the 13 issues. The highest need (expressed as percentage of women who rated an item as moderately or extremely important) was for information about recognizing a recurrence (90%), chances of cure (82%), and risk to family of breast cancer (81%), as described in Table 2. The lowest need was expressed for information about breast reconstruction (36%), sexuality and relationships (39%) and prostheses (41%), although it should be noted that more than one‐third of respondents rated these lowest ranked items as moderately or extremely important. Recognizing a recurrence was most frequently chosen as the single most important area of information, followed by chances of cure, arm problems and lymphoedema, and breast reconstruction.

Table 2.

Need for information and extent of information received

| Issue (N = 217*) | Rated item as moderately/extremely important* | Received information within previous 6 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Recognizing a recurrence | 191 | 90 | 85–94 | 27 | 13 | 9–19 |

| Chances of cure | 167 | 82 | 76–87 | 66 | 32 | 26–39 |

| Risk to family of breast cancer | 167 | 81 | 75–86 | 25 | 12 | 8–17 |

| Tamoxifen and other antioestrogen drugs | 148 | 72 | 65–78 | 54 | 26 | 20–32 |

| Effect on family of breast cancer | 142 | 68 | 61–74 | 27 | 13 | 9–18 |

| Arm problems and lymphoedema | 132 | 64 | 57–70 | 33 | 16 | 11–22 |

| Where to go for additional support | 128 | 64 | 57–71 | 43 | 21 | 16–28 |

| Physical appearance after surgery | 121 | 58 | 51–65 | 44 | 21 | 16–28 |

| Complementary and alternative therapies | 105 | 51 | 44–58 | 32 | 15 | 11–21 |

| Menopause and hormone replacement therapy | 100 | 50 | 43–57 | 17 | 8 | 5–13 |

| Prostheses | 82 | 41 | 34–48 | 36 | 18 | 13–24 |

| Sexuality and relationships | 81 | 39 | 32–46 | 5 | 2 | 1–6 |

| Breast reconstruction | 74 | 36 | 30–43 | 24 | 12 | 8–17 |

*Varying levels of non‐response in each category.

Despite rating these issues as important, few women reported receiving information about any of the 13 issues within the previous 6 months. The percentage ranged from 2% who reported receiving information about sexuality and relationships up to 32% who reported receiving information about chances of cure.

Sources of information

Women used a variety of sources for information. Frequency of use and extent of satisfaction with these sources are described in Table 3. The most frequently used information source was the surgeon, being used by 60% of women in the previous 6 months. Other frequently used sources of information were television (56%), magazines (45%), newspapers (32%), books (32%) and the GP (32%).

Table 3.

Sources of information used and satisfaction with those sources (ranked by frequency of use)

| Source of information (N = 217) | Received information within previous 6 months | Satisfaction with information* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Surgeon | 125 | 60 | 53–67 | 111 | 92 | 85–96 |

| Television | 114 | 56 | 49–63 | 52 | 46 | 37–56 |

| Magazines | 91 | 45 | 38–52 | 52 | 58 | 47–68 |

| Newspapers | 66 | 32 | 26–39 | 34 | 52 | 40–65 |

| GP | 65 | 32 | 25–38 | 57 | 89 | 79–95 |

| Books | 64 | 32 | 25–39 | 48 | 77 | 65–87 |

| Cancer specialist | 49 | 25 | 19–32 | 40 | 83 | 70–93 |

| Friends | 46 | 23 | 17–29 | 34 | 78 | 64–89 |

| Brochures | 44 | 22 | 17–29 | 40 | 93 | 81–99 |

| Radio | 44 | 22 | 16–28 | 25 | 60 | 43–74 |

| Breast care nurse | 37 | 18 | 13–24 | 30 | 83 | 67–94 |

| Family | 24 | 12 | 8–17 | 21 | 92 | 73–99 |

| Alternative/complementary practitioner | 19 | 9 | 6–14 | 17 | 89 | 67–99 |

| Cancer telephone information service | 10 | 5 | 2–9 | 8 | 73 | 39–94 |

| Support group | 10 | 5 | 2–9 | 10 | 100 | 69–100** |

| Peer support programme volunteer | 9 | 4 | 2–8 | 6 | 75 | 35–97 |

| Internet | 9 | 4 | 2–8 | 8 | 89 | 52–100 |

*Satisfaction = (number of women who rated information received from that source as moderately or extremely useful/total number of women who received information from that source) expressed as a percentage.

* *One sided 97.5% CI.

The highest levels of satisfaction (expressed as the proportion of women who reported the information to be moderately or extremely useful) were for information received from breast cancer support groups (100%), brochures (93%), the surgeon (92%), family (92%), GP (89%), alternative and complementary practitioners (89%) and the Internet (89%). While women were very satisfied with the information they received from a number of sources including the surgeon and other health professionals, they were less satisfied with information received from the media. The lowest levels of satisfaction were for information received from television (46%), newspapers (52%), magazines (58%) and radio (60%). The surgeon was most frequently chosen as the single most helpful source of information followed by books, the GP and other women with breast cancer.

Sources of support

The frequency of use of and extent of satisfaction with sources of support are described in Table 4. The most frequently used sources of support were the family (81%) followed by friends (71%) and the surgeon (70%). The least frequently used sources of support were the Internet (2%), peer support programme volunteer (3%), cancer telephone information service (4%), breast cancer support group (5%) and psychiatrist or psychologist (5%).

Table 4.

Sources of support used and satisfaction with those sources (ranked by frequency of use)

| Source of support (N = 217) | Received support within previous 6 months | Satisfaction with support* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Family | 164 | 81 | 75–86 | 143 | 92 | 87–96 |

| Friends | 145 | 71 | 64–77 | 117 | 84 | 77–90 |

| Surgeon | 145 | 70 | 63–76 | 128 | 93 | 87–96 |

| GP | 107 | 52 | 45–59 | 94 | 91 | 84–96 |

| Cancer specialist | 57 | 29 | 23–36 | 52 | 98 | 90–100 |

| Breast care nurse | 47 | 24 | 18–30 | 40 | 87 | 74–95 |

| Alternative/complementary practitioner | 29 | 14 | 10–20 | 26 | 90 | 73–98 |

| Psychiatrist/psychologist | 9 | 5 | 3–10 | 10 | 91 | 59–100 |

| Support group | 9 | 5 | 2–9 | 7 | 70 | 35–93 |

| Cancer telephone information service | 9 | 4 | 2–8 | 6 | 67 | 30–93 |

| Peer support programme volunteer | 6 | 3 | 1–6 | 5 | 83 | 36–100 |

| Internet | 5 | 2 | 1–6 | 4 | 80 | 28–100 |

*Satisfaction = (number of women who rated support received from that source as moderately or extremely helpful/total number of women who received support from that source) expressed as a percentage.

Women were generally very satisfied with the support they received. The highest levels of satisfaction (expressed as the proportion of women who reported support as moderately or extremely helpful) were for the cancer specialist (98%), surgeon (93%), family (92%), GP (91%), psychiatrist or psychologist (91%) and breast care nurse (87%). The lowest levels of satisfaction were for the cancer telephone information service (67%) and breast cancer support group (70%) although again it should be noted that over two‐thirds of women were satisfied with the support provided. Women nominated a variety of sources as the single most important source of support. Most frequently nominated were the family, followed by the surgeon, GP, and friends, particularly other women with breast cancer.

Less than 7% of women used the Internet, peer support programme volunteer, cancer telephone information service or breast cancer support group for either information or support.

Trends with time since diagnosis

Women continued to report a high level of need for information about most issues with increasing time since diagnosis except for information about sexuality and relationships where women expressed less need for information with increasing time since diagnosis (Mantel test for trend of odds = 4.75, P = 0.03, d.f. = 1).

Women were significantly less likely to report receiving information for eight of the 13 issues examined as the time since diagnosis increased from 6 to 30 months, despite the minimal change in expressed need for information over time (Table 5). These eight issues were: chances of cure, risk to family of breast cancer, tamoxifen and other antioestrogen drugs, effect on family of breast cancer, where to go for additional support, arm problems and lymphoedema, physical appearance after surgery, and prostheses.

Table 5.

Information received about particular issues by time since diagnosis

| Issue | Received information within previous 6 months Time since diagnosis in months | Chi‐square test** | Mantel test*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 N = 47* % 95% CI | 12–17 N = 57* % 95% CI | 18–23 N = 47* % 95% CI | ≥24 N = 66* % 95% CI | |||

| Recognizing a recurrence | 16 | 12 | 9 | 16 | 1.78 | 0.00 |

| 7–31 | 4–23 | 2–20 | 8–27 | P = 0.62 | P = 0.98 | |

| Chances of cure | 48 | 35 | 24 | 25 | 7.84 | 6.55 |

| 32–63 | 22–50 | 13–39 | 15–38 | P = 0.05 | P = 0.01 | |

| Risk to family of breast cancer | 27 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 11.82 | 4.14 |

| 15–42 | 1–15 | 2–21 | 4–21 | P = 0.01 | P = 0.04 | |

| Tamoxifen and other antioestrogen drugs | 47 | 24 | 13 | 22 | 14.59 | 7.78 |

| 32–62 | 13–38 | 5–26 | 13–34 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.01 | |

| Effect on family of breast cancer | 26 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 9.62 | 7.74 |

| 14–41 | 4–23 | 4–23 | 2–16 | P = 0.02 | P = 0.01 | |

| Where to go for additional support | 48 | 19 | 11 | 12 | 24.37 | 17.38 |

| 32–63 | 9–32 | 4–24 | 5–23 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.00 | |

| Arm problems and lymphoedema | 38 | 13 | 9 | 8 | 20.77 | 15.10 |

| 24–53 | 6–26 | 2–21 | 3–18 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.00 | |

| Physical appearance after surgery | 41 | 19 | 17 | 13 | 13.27 | 10.25 |

| 26–57 | 9–33 | 8–31 | 6–24 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.00 | |

| Complementary and alternative therapies | 13 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| 5–27 | 8–30 | 6–29 | 8–26 | P = 0.96 | P = 0.89 | |

| Menopause and hormone replacement therapy | 14 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 4.70 | 0.05 |

| 5–29 | 0–14 | 1–15 | 5–22 | P = 0.20 | P = 0.82 | |

| Prostheses | 31 | 20 | 9 | 15 | 8.01 | 5.07 |

| 18–47 | 10–34 | 2–21 | 7–26 | P = 0.05 | P = 0.02 | |

| Sexuality and relationships | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2.68 | 0.73 |

| 0–12 | 0–13 | 0–15 | 0–6**** | P = 0.44 | P = 0.39 | |

| Breast reconstruction | 11 | 10 | 17 | 10 | 1.76 | 0.00 |

| 4–25 | 3–21 | 8–31 | 4–20 | P = 0.62 | P = 0.98 | |

*Varying levels of non‐response in each category.

* *Chi‐square, 3 d.f.

* * *Mantel test = Mantel test for trend of odds, 1 d.f.

* * * *One‐sided, 97.5% CI.

The sources of information used by women changed with increasing time since diagnosis as shown in Table 6. The proportion of women who reported receiving information from the surgeon, cancer specialist, breast care nurse, peer support programme volunteer, books, brochures and friends decreased with increasing time from diagnosis (P < 0.05). Similarly a decreasing proportion of women reported receiving support from most health professionals with increasing time from diagnosis, although the proportion of women receiving support from the surgeon did not change. No changes occurred over time with respect to satisfaction with information or with respect to satisfaction with support.

Table 6.

Sources of information used by time since diagnosis

| Source | Received information within previous 6 months Time since diagnosis in months | Chi‐square test** | Mantel test*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 N = 47* % 95% CI | 12–17 N = 57* % 95% CI | 18–23 N = 47* % 95% CI | 24–30 N = 66* % 95% CI | |||

| Surgeon | 86 | 57 | 52 | 50 | 16.70 | 12.19 |

| 73–95 | 43–70 | 37–67 | 37–63 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.00 | |

| Cancer specialist | 60 | 23 | 16 | 9 | 36.62 | 29.79 |

| 43–74 | 13–37 | 7–30 | 3–19 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.00 | |

| GP | 43 | 36 | 24 | 25 | 5.64 | 4.86 |

| 28–59 | 23–50 | 13–39 | 15–38 | P = 0.13 | P = 0.27 | |

| Breast care nurse | 34 | 20 | 14 | 8 | 12.11 | 11.40 |

| 20–50 | 11–34 | 5–27 | 3–18 | P = 0.01 | P = 0.00 | |

| Alternative/complementary practitioner | 14 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 1.67 | 1.10 |

| 5–28 | 3–20 | 1–18 | 3–18 | P = 0.64 | P = 0.30 | |

| Peer support programme volunteer | 12 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6.96 | 5.13 |

| 4–25 | 0–13 | 0–12 | 0–9 | P = 0.07 | P = 0.02 | |

| Cancer telephone information service | 9 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4.53 | 4.14 |

| 3–22 | 2–18 | 0–12 | 0–9 | P = 0.21 | P = 0.04 | |

| Support group | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 1.82 | 0.38 |

| 1–19 | 0–13 | 1–18 | 0–12 | P = 0.76 | P = 0.54 | |

| Books | 56 | 30 | 20 | 25 | 15.98 | 10.39 |

| 40–71 | 18–44 | 9–34 | 15–38 | P = 0.00 | P = 0.00 | |

| Magazines | 49 | 43 | 51 | 40 | 1.67 | 0.39 |

| 33–65 | 29–57 | 36–66 | 28–53 | P = 0.64 | P = 0.53 | |

| Brochures | 41 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 11.23 | 6.14 |

| 26–58 | 8–30 | 8–31 | 8–29 | P = 0.01 | P = 0.01 | |

| Newspapers | 33 | 28 | 33 | 35 | 0.73 | 0.24 |

| 20–48 | 16–42 | 29–48 | 23–48 | P = 0.87 | P = 0.63 | |

| Television | 53 | 55 | 54 | 60 | 0.60 | 0.44 |

| 38–69 | 41–68 | 39–69 | 47–72 | P = 0.90 | P = 0.51 | |

| Radio | 14 | 26 | 22 | 23 | 2.18 | 0.66 |

| 5–28 | 15–40 | 11–36 | 13–36 | P = 0.54 | P = 0.42 | |

| Internet | 7 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1.43 | 0.01 |

| 1–18 | 0–10 | 0–15 | 1–14 | P = 0.70 | P = 0.93 | |

| Family | 18 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 2.90 | 0.68 |

| 8–32 | 2–18 | 5–27 | 4–20 | P = 0.41 | P = 0.41 | |

| Friends | 38 | 22 | 22 | 13 | 8.86 | 7.61 |

| 24–54 | 12–36 | 11–37 | 6–24 | P = 0.03 | P = 0.01 | |

*Varying levels of non‐response in each category.

* *Chi‐square, 3 d.f.

* * *Mantel test = Mantel test for trend of odds, 1 d.f.

Trends with age

Women over 69 years expressed lower needs for specific items of information compared with women aged 50–69. Theses differences were the greatest with respect to information about: sexuality and relationships [3% vs. 41%, prevalence rate ratio (PRR) 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–0.52], breast reconstruction (38% vs. 3%, PRR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01–0.56), menopause and hormone replacement therapy (10% vs. 50%, PRR 0.20, 95% CI 0.07–0.60) and physical appearance (20% vs. 63%, PRR 0.32, 95% CI 0.16–0.63).

The pattern was less clear for younger women under 50. Generally women under 50 reported a similar level of need for specific items of information compared with women aged 50–69. However, compared with women aged 50–69, women under 50 reported a higher need for information about: complementary and alternative therapies (71% vs. 53%, PRR 1.34, 95% CI 1.12–1.83), menopause and hormone replacement therapy (72% vs. 50%, PRR 1.43, 95% CI 1.12–1.83), sexuality and relationships (59% vs. 41%, PRR 1.45, 95% CI 1.06–1.98), and breast reconstruction (54% vs. 38%, PRR 1.43, 95% CI 1.02–2.02).

Overall there was a (non‐significant) trend for a greater proportion of women aged 50–69 to report receiving information compared with older and younger women. Compared with women aged 50–69, women over 69 were significantly less likely to report receiving information about two issues: physical appearance after surgery (6% vs. 27%, PRR 0.24, 95% CI 0.06–0.94) and where to go for additional support (6% vs. 28%, PRR 0.23, 95% CI 0.06–0.92). Women under 50 were significantly less likely to report receiving information about the chances of cure compared with women aged 50–69 (20% vs. 38%, PRR 0.53, 95% CI 0.29–0.97). An exception to the overall trend occurred with respect to information about alternative and complementary therapies, sexuality and relationships and breast reconstruction. For these three issues there was a (non‐significant) trend for a greater proportion of women under 50 to report receiving information compared with women aged 50–69.

Small differences were noted in the proportion of women of different ages who reported using particular sources of information. Compared with women aged 50–69, women under 50 were more likely to report receiving information from newspapers (51% vs. 27%, PRR 1.90, 95% CI 1.27–2.84), magazines (65% vs. 39%, PRR 1.66, 95% CI 1.23–2.24), and television (71% vs. 54%, PRR 1.33, 95% CI 1.05–1.69). Women over 69 were less likely to report receiving information, compared with women aged 50–69, from the breast care nurse (6% vs. 24%, PRR 0.24, 95% CI 0.06–0.96), books (3% vs. 35%, PRR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.64), brochures (6% vs. 27%, PRR 0.24, 95% CI 0.06–0.93) and the surgeon (47% vs. 69%, PRR 0.69, 95% CI 0.48–0.99). Women under 50 were also less likely to report receiving information from the surgeon compared with women aged 50–69 (48% vs. 69%, PRR 0.70, 95% CI 0.51–0.96). Notably women of all ages were equally satisfied with the support provided by the surgeon.

There was little variation in frequency of use of different sources of support by age. An exception occurred for women under 50 who were more likely to report receiving support from alternative and complementary practitioners than women aged 50–69 (32% vs. 10%, PRR 3.3, 95% CI 1.67–6.51).

Experiences of information and support

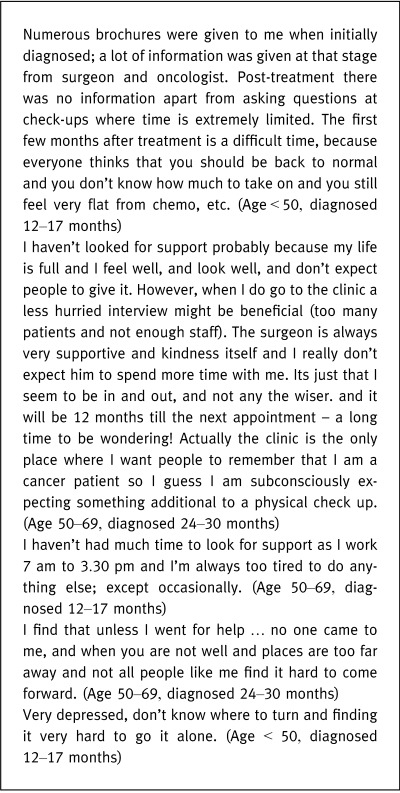

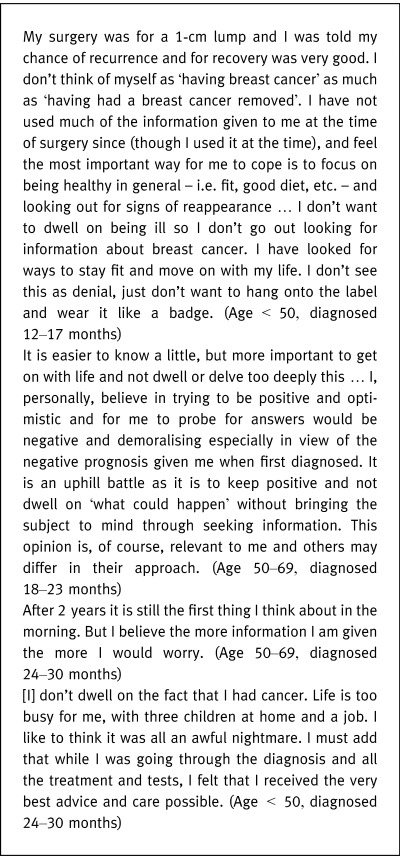

One hundred and sixty‐six (76%) respondents provided some response to open‐ended items asking about where they had looked for information and support and how helpful it had been. While these women do not represent a systematic or purposive sample, their comments provide some insight into women's need for and experience of information and support. Some women commented on difficulties they encountered in obtaining information and/or support. These included time constraints during medical follow‐up, demands of the respondents' busy lifestyles and psychological barriers (see Box 1). Other women stated that they did not wish to look for further information and/or support. Some considered that their needs had been met already through existing services; others expressed a preference to get on with living, while others perceived the provision of information about breast cancer as a source of worry (see Box 2).

Figure Box 1. .

Difficulties encountered in seeking out and obtaining information and support

Figure Box 2. .

Reasons for not seeking further information and/or support

Discussion

As the number of surviving women with breast cancer increase, it is important to explore women's needs for information and support following treatment and the ways in which women meet those needs. Exploring need rather than satisfaction offers advantages in being able to directly assess gaps in services, being able to directly compare the magnitude of need for help in different areas and in being able to compare levels of need among different groups of people. 39

This study shows that women continue to have high need for information about a variety of breast cancer related issues following the diagnosis of breast cancer. Furthermore these needs remain largely unmet as few women receive information about the issues that concern them. As in previous UK and Canadian studies of women further from diagnosis of breast cancer, survival issues such as recognizing a recurrence, chances of cure and risk to family members of breast cancer are considered most important. 12 , 15 However quality of life issues such as breast reconstruction; arm problems and lymphoedema; and sexuality and relationships are also of high importance for many women. In this survey over 30% of respondents expressed a high level of need for each of the 13 issues examined.

This study confirms the results of previous studies and demonstrates that women are more satisfied with the information that they receive through personal contact compared with printed sources or the electronic media. 16 In particular women are very satisfied with the information and support that they receive from health professionals. In this study the surgeon was the most frequently used and most important source of information for women while the surgeon and GP were the most frequently used sources of support after family and friends. These findings highlight the importance that women place on receiving information in a supportive and caring context. In the clinical encounter, information can be tailored to meet the needs and preferences of individual women. Furthermore health professionals are a credible and trusted source of information for most women.

We found that most women indicate a high need for information about breast cancer issues over time following the primary treatment of breast cancer. However, these needs remain largely unmet as women report receiving decreasing amounts of information and support from a range of sources and decreasing amounts of information about a number of important issues over time. While women with breast cancer are provided with large amounts of information and support at diagnosis, they receive decreasing amounts further from the time of diagnosis. In particular contact with health professionals diminishes with time. Women report receiving less information from the surgeon, cancer specialist and breast care nurse and receiving less support from the cancer specialist, GP and breast care nurse over time. Factors such as a lack of time at clinic visits, a general reluctance to ask questions and feeling too unwell to ask questions may contribute to this decrease in information and support received with time.

Time and resource constraints are critical factors that limit the amount of information and support that can be provided in the clinical context. More extensive use of the breast care nurse during follow‐up visits to specialist clinics could help to reduce the level of unmet need experienced by women. Increased use of GPs in breast cancer follow‐up could allow for greater opportunity to provide information and support as well as ease the pressure on the resources of specialist breast clinics. GP follow‐up care is not associated with any deterioration in survival or quality of life compared with specialist follow‐up. 40 Other mechanisms that could provide more information and support are the use of consumer advocates in the breast clinic and increased use of formal support services such as breast cancer support groups, cancer telephone information services and volunteer peer support programmes.

We found that few women use formal support services or the Internet for either information or support. However, those who do are very satisfied with the information and support they receive. The use of breast cancer support groups does not decrease with time. Many breast cancer support groups include both an informational and supportive component and expansion of these services is likely to be valuable in meeting women's information and support needs following the primary treatment of breast cancer.

A particular strength of this study was the use of a cohort sample, together with a high response rate. As a result we collected a representative sample of women that included both users and non‐users of information and support. Furthermore the sample size was adequate to provide precise estimates of common variables and to examine broad time trends in information and support since diagnosis.

There were a number of limitations of the study. The use of cross‐sectional rather than a longitudinal design was a limitation in examining changes with time since diagnosis and did not take into account cohort effects by year of birth. Furthermore the generalizability of the study may be limited by not assessing women treated in the private sector. Women living in rural areas were under‐represented and non‐literate women were likely to be under‐represented because of administration of the questionnaire by post.

Conclusion

The role of the health professional, particularly the surgeon, is critical in providing information and support. Information provided in this setting can be tailored to meet the needs and preferences of individual women and can be offered within a supportive context. There needs to be greater time and opportunity for the provision of information and support within medical follow‐up to discuss the issues that concern women. More extensive use of the breast care nurse during follow‐up visits to specialist clinics and expansion of the GP role in follow‐up could help to further reduce the level of unmet need experienced by women.

These results provide a basis for developing effective models to routinely deliver information and support about psychosocial and other ‘survivorship issues’ to women who have completed primary treatment for breast cancer. The identification of important information and support needs enables follow‐up health services and other resources to be targeted more efficiently to meet those needs. Specific knowledge of women's needs may also guide the development of effective psychosocial interventions that improve outcomes for women with breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Stephen Birrell and Prof. David Weller for providing comments and advice, the clinic staff for administrative support and most importantly the women who participated so willingly in the study.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1. Steginga S, Occhipinti S, Wilson K, Dunn J. Domains of distress: the experience of breast cancer in Australia. Oncology Nursing Forum , 1998; 25: 1063 – 1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rendle K. Survivorship and breast cancer: the psychosocial issues. Journal of Clinical Nursing , 1997; 6: 403 – 410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ganz PA, Coscarelli A, Fred C, Kahn B, Polinsky ML, Petersen L. Breast cancer survivors: psychosocial concerns and quality of life. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment , 1996; 38: 183 – 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyer TJ, Mark MM. Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: a meta‐analysis of randomised experiments. Health Psychology , 1995; 42: 101 – 108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Devine FC, Westlake SK. The effects of psycho‐educational care provided to adults with cancer: a meta‐analysis of 116 studies. Oncology Nursing Forum , 1995; 22: 1369 – 1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Arndt LA, Pasnau RO. Critical reviews of psychosocial interventions in cancer care. Archives of General Psychiatry , 1995; 52: 100 – 113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burke S, Kissane D. Psychosocial Support for Breast Cancer Patients. A Review of Interventions by Members of the Treatment Team. Woolloomooloo, Sydney: NHMRC National Breast Cancer Centre, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burke S, Kissane D. Psychosocial Support for Breast Cancer Patients: a Review of Interventions by Specialist Providers. Woolloomooloo, Sydney: NHMRC National Breast Cancer Centre, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graydon J, Galloway S, Palmer‐Wickam S et al. Information needs of women during early treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 1997; 26: 59 – 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hack TF, Denger LF, Dyck DG. Relationship between preferences for decisional control and illness information among women with breast cancer: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Social Science and Medicine , 1994; 39: 279 – 289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters‐Golden H. Varied perceptions of social support in the illness experience. Social Science and Medicine , 1982; 16: 483 – 491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Denger LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D et al. Informational needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association , 1997; 277: 1485 – 1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Girgis A, Boyes A, Sanson‐Fisher RW, Burrows S. Perceived needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer; rural versus urban location. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health , 2000; 24: 166 – 173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luker KA, Beaver K, Leinster SJ, Owens RG, Denger LF, Sloan JA. The information needs of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 1995; 22: 134 – 141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luker K, Beaver K, Leinster SJ, Owens RG. Information needs and sources of information for women with breast cancer: a follow‐up study. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 1996; 23: 487 – 495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bilodeau BA, Denger LF. Information needs, sources of information and decisional roles in women with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum , 1996; 23: 691 – 696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, Kaplan SH. Breast cancer care in older women: sources of information, social support, and emotional outcomes. Cancer , 1998; 83: 706 – 711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neuling SJ, Winefield HR. Social support and recovery after surgery from breast cancer: frequency and correlates of supportive behaviours by family friends and surgeon. Social Science and Medicine , 1988; 27: 385 – 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunkel‐Schetter C. Social support and cancer: findings based on patient interviews and their implications. Journal of Social Issues , 1984; 40: 77 – 98. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dakof GA, Taylor SE. Victims' perception of social support: what is helpful from whom? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1990; 58: 80 – 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slevin ML, Nichols SE, Downer SM et al. Emotional support for cancer patients: what do patients really want? British Journal of Cancer , 1996; 74: 1275 – 1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suominen T, Leino‐Kilpi H, Laippala P. Who provides support and how? Breast cancer patients and nurses evaluate patient support. Cancer Nursing , 1995; 18: 278 – 285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goldberg R, Guandagnoli E, Silliman RA, Glicksman A. Cancer patients concerns: congruence between patients and primary care physicians. Journal of Cancer Education , 1990; 5: 193 – 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Girgis A, Foot G. Satisfaction with Breast Cancer Care: a Summary of the Literature. Kings Cross: NHMRC National Breast Cancer Centre, 1995, pp. 1984 – 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray RE, Fitch M, Greenburg M, Hampson A, Doherty M, Labrecque M. The information needs of well, longer‐term survivors of breast cancer. Patient Education and Counselling , 1998; 33: 245 – 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butow PN, MacLean M, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH, Boyer MJ. The dynamics of change: cancer patients' preferences for information, involvement and support. Annals of Psychology , 1997; 8: 857 – 863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wortman C. Social support and the cancer patient: conceptual and methodological issues. Cancer , 1984; 53: 2339 – 2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Helgeson V, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: reconciling descriptive, correlational and intervention research. Health Psychology , 1996; 15: 135 – 148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. South Australian Cancer Registry. Epidemiology of Cancer in South Australia 1977–97. Adelaide: Department of Human Services, Government of South Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30. South Australian Cancer Registry. Epidemiology of Cancer in South Australia 1977–98. Adelaide: Department of Human Services, Government of South Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Breast Cancer Network Australia, NHMRC National Breast Cancer Centre. Report from the Conference: Actions Recommended by Women with Breast Cancer for the Benefit of the Australian Community. Australia's First National Breast Cancer Conference for Women, Canberra, Australia, October 16–18, 1998. Woolloomooloo: NHMRC National Breast Cancer Centre, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 5.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 6.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Foot G, Sanson‐Fisher R. Measuring the unmet needs of people living with cancer. Cancer Forum , 1995; 19: 131 – 135. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sanson‐Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P and the Supportive Care Review Group. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer , 2000; 88: 226 – 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elwood M. Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials, 2nd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Berg BL. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 3rd edn Needham Heights MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care National Key Centre for Social Applications of Geographical Information Systems. Measuring Remoteness: Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA). Occasional Papers New Series, No. 6. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonevski B, Sanson‐Fisher R, Girgis A, Burton L, Cook P, Boyes A, the Supportive Care Review Group. Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Cancer , 2000; 88: 217 – 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grunfeld E, Mant D, Yudkin P et al. Routine follow‐up of breast cancer in primary care: randomised trial. British Journal of Medicine , 1996; 316: 665 – 669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]