Abstract

This study examined reciprocal support networks involving extended family, friends and church members among African Americans. Our analysis examined specific patterns of reciprocal support (i.e., received only, gave only, both gave and received, neither gave or received), as well as network characteristics (i.e., contact and subjective closeness) as correlates of reciprocal support. The analysis is based on the African American sub-sample of the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). Overall, our findings indicate that African Americans are very involved in reciprocal support networks with their extended family, friends and church members. Respondents were most extensively involved in reciprocal supports with extended family members, followed closely by friends and church networks. Network characteristics (i.e., contact and subjective closeness) were significantly and consistently associated with involvement with reciprocal support exchanges for all three networks. These and other findings are discussed in detail. This study complements previous work on the complementary roles of family, friend and congregational support networks, as well as studies of racial differences in informal support networks.

Extended family members are an important source of informal support to African Americans. Research has found African American families are important when coping with mental health problems (Chatters, Taylor, Woodward, & Nicklett, 2015; Levine, Taylor, Nguyen, Chatters, & Himle, 2015; Lincoln, Taylor, Chatters, & Joe, 2012; Taylor, Chae, Lincoln, & Chatters, 2015; Woodward et al., 2008) as well as providing economic assistance (O'Brien, 2012), emotional support and tangible services to meet the challenges of daily life (Lincoln, Taylor, & Chatters, 2013; Taylor, Chatters, Woodward, & Brown, 2013). The vast majority of research on social support among African Americans investigates the receipt of support from extended family members, with considerably less attention on the role of friends and church members in social support networks. Further, research tends to be one-directional, focusing on either providing or receiving support. Investigations of reciprocal patterns of support involving family, friends and church members, are especially scarce. The goal of this study is to investigate the correlates of reciprocal support exchanges involving family, friends and church members using data from a national sample of African American adults. The literature review begins with a discussion of research on reciprocal support between family members, followed by research on friendship networks and church-based informal support networks. Next, we present information on social exchange theory as a framework for examining patterns of reciprocal support. The literature review concludes by discussing the focus of the present investigation.

Research on Reciprocal Support between Family Members

Social support exchanges tend to be equitable (Boerner & Reinhardt, 2003; Gleason, Iida, Bolger, & Shrout, 2003; Keyes, 2002). People who provide high levels of support to members of their social networks are likely to similarly receive high levels of support, while those who provide low levels of support are likely to receive comparable levels of support from network members. In a study of support reciprocity in older adults, Ingersoll-Dayton and colleagues (1988) found that spousal relationships are most likely to involve reciprocal support patterns (85%), followed by adult children (67%) and friends (63%). Although most supportive relationships are, in fact, reciprocal, people generally perceive that they provide more support than they receive. Moreover, for relationships that are not reciprocal, people tend to report that they provide more support than they receive, rather than the reverse (Ingersoll-Dayton & Antonucci, 1988).

Findings from race comparative studies suggest that among older adults, Whites are more likely than African Americans to perceive their relationships as reciprocal (Antonucci, Fuhrer, & Jackson, 1990). In contrast, African Americans are more likely than their White counterparts to perceive that they receive less support (Antonucci et al., 1990). Some studies, however, indicate that older African Americans are more likely than older Whites to report that their relationships are reciprocal (Fiori, Consedine, & Magai, 2008). This is also consistent with findings from non-geriatric populations (Hogan, Eggebeen, & Clogg, 1993) indicating that while African Americans perceive their relationships to be reciprocal, they tend to exchange less support than Whites. Finally, in one of the more comprehensive studies of this issue, Sarkisian and Gerstel (2004) found that African Americans and Whites have different patterns of reciprocal support from family networks. Specifically, African Americans are more involved with giving and receiving child care, household work and transportation, whereas Whites are more likely to be involved with emotional and financial support.

African American Friendship Networks

Very little research explores the nature of friendships among adult African Americans and, similar to research on family networks, the majority of this work focuses on racial differences. Available research indicates that, on average, non-Hispanic Whites are more likely to be involved with friendship networks than African Americans (Griffin, Amodeo, Clay, Fassler, & Ellis, 2006; Waite & Harrison, 1992). A recent analysis (Taylor et al., 2013) indicates that non-Hispanic Whites interacted with friends, gave support to friends and received support from friends more frequently than African Americans. Although studies in this area provide important information regarding Black-White differences in friend relations and support, they leave unanswered important questions regarding the correlates of friendship support networks among African Americans.

African American Church Based Networks

Church members are an important resource for African Americans. Data from the National Survey of Black Americans found that two thirds of African Americans receive some level of support from church members (Chatters, Taylor, Lincoln, & Schroepfer, 2002). Church members provide emotional support (e.g., companionship, encouragement), information and advice, and instrumental support (e.g., transportation, goods, services) (Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004). Some of the most common types of support exchanged between African Americans congregants are advice and encouragement, companionship, assistance during illness, prayers, and financial aid (Krause, 2008; Taylor et al., 2004). Although there is a relatively extensive body of research on church based support networks there remains limited to no information on reciprocal support between church members.

Social Exchange Theory and Reciprocal Support

Social exchange theory, with origins in social psychology, psychology, and economics, provides important insights regarding the nature of social relationships and the benefits of social support. Social exchange theory proposes that individuals attempt to maximize their benefits from social relationships (Becker, 1974; Homans, 1958) through a process of cost-benefit analysis, weighing the advantages and disadvantages of investing in the relationship. As a part of this cognitive deliberation process, the availability and desirability of other support alternatives are also evaluated. According to social exchange theory, the likelihood that a social bond will be initiated increases when there is: 1) a belief that a social relationship would garner maximum gains and minimal losses and 2) the perception that options for other sources of support are limited. Applied to social support exchanges, anticipated gains from the relationship can involve either restricted/similar exchange of the same resource (e.g., the provision and receipt of emotional support) or generalized/mixed exchanges (e.g., the provision of instrumental support and the receipt of emotional support). In terms of issues of reciprocity, social exchange theory suggests that individuals are happiest in social relationships that are characterized by equal levels of giving and receiving support (e.g., Homans, 1958).

Focus of the Present Study

The present study investigates the correlates of reciprocal support in extended family, friendship and church networks among African Americans. The analysis is based on the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), a nationally representative sample of African Americans. Multivariate analyses control for both relevant social network (e.g., frequency of interaction, degree of closeness) and demographic variables that are known to be associated with variability in informal support networks. To our knowledge this is the first analysis of reciprocal support that includes friendships and church networks, as well as family networks and, further, one of the few studies that is based on a national probability sample of African Americans.

Drawing on previous research, we anticipate that both network and demographic variables will be significantly associated with involvement with reciprocal support networks. Because the vast majority of research on informal social support has been conducted on family networks, our expectations are mostly based on this literature. Our analysis includes two network variables, subjective closeness and frequency of contact. We expect that both of these network variables will be positively associated with involvement in reciprocal support networks. This is consistent with research on family networks which has found that both subjective family closeness and the frequency of contact with family members leads to more integration in family networks (Lincoln, Taylor & Chatters, 2013). This higher level of family integration leads to more giving and receiving of support. Research on church-based informal support networks also indicates that church members who interact with each other more often and who feel subjectively closer receive more assistance from their church member network (Taylor et al., 2005).

With regard to demographic factors, we expect that women will be more likely to be involved in reciprocal support networks than men. Women are more involved in family, friendship and church member networks than men and thus may be more involved in these reciprocal support networks. This gender difference, however, may be ameliorated when network closeness and contact are controlled. Previous research has found very few socio-economic status differences in family support networks. There was a general expectation based upon early ethnographic work (Stack, 1975) that lower socio-status individuals would be more involved in family networks, but that has not been confirmed in large scale survey research (Lincoln, Taylor & Chatters, 2013). The lack of available research studies on socio-economic status differences in friendship and church support networks among African Americans limits our ability to posit clear hypotheses about SES effects on reciprocal support patterns. With respect to age differences, we have no clear expectation regarding how age is associated with reciprocal support. However, research on intergenerational relationships (Bengtson et al., 2002; Kahn et al., 2011) notes the importance of the elderly adult and adult child bond for social support exchanges. Consequently, we included an interaction term between parental status and age in all of our analysis. This is consistent with previous research on the receipt of support from family among African Americans (Taylor, 1986). We expect that this interaction will be significant for involvement in family reciprocal support networks, but not with friendship or church based networks.

METHODS

Sample

The National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) was collected by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research (Jackson, Neighbors, Nesse, Trierweiler, & Torres, 2004). The field work for the study was completed by the Institute of Social Research’s Survey Research Center, in cooperation with the Program for Research on Black Americans. The NSAL sample has a national multi-stage probability design. Most of the interviews were conducted face-to-face (86%) within respondents’ homes while the remaining 14% were telephone interviews. Respondents were compensated for their time. The data collection was conducted from 2001 to 2003. A total of 6,082 interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older. This paper utilizes the African American sub-sample (n=3,570). The African American sample is the core sample of the NSAL. The core sample consists of 64 primary sampling units (PSUs). Fifty-six of these primary areas overlap substantially with existing Survey Research Center’s National Sample primary areas. The remaining eight primary areas were chosen from the South in order for the sample to represent African Americans in the proportion in which they are distributed nationally.

The overall response rate was 72.3%. The response rate for African Americans was 70.7%. This response rate is excellent considering that African Americans (especially lower income African Americans) are more likely to reside in major urban areas which are more difficult and much more expensive to collect interviews. Final response rates for the NSAL two-phase sample designs were computed using the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAAPOR) guidelines (for Response Rate 3) (AAPOR, 2006) (see Jackson et al., 2004 for a more detailed discussion of the NSAL sample).

Measures

Dependent Variables

In this analysis, reciprocal support relationships are examined in relation to three types of support networks: reciprocal support with family, reciprocal support with friends and reciprocal support with church members. The variable for reciprocal support with extended family members is created by combining a measure of frequency of receiving support from extended family members with a measure of frequency of giving support to extended family members. Frequency of receiving support is assessed by the question: “How often do people in your family -- including children, grandparents, aunts, uncles, in-laws and so on -- help you out? Would you say very often, fairly often, not too often, or never?” Frequency of giving support is measured by the question: “How often do you help out people in your family -- including children, grandparents, aunts, uncles, in-laws and so on? Would you say very often, fairly often, not too often, or never?” Both questions were recoded by combining the response categories: (1) very often, fairly often, not too often vs. (2) never. This results in two binary variables, received support from family: Yes/No and give support to family: Yes/No. These two questions were combined into single, four-category pattern variable measuring reciprocal support with extended family members. The four categories represent respondents who: 1) Both Give and Receive Support, 2) Only Receive Support, 3) Only Give Support, or 4) Neither Receive or Give Support.

Comparable questions for receiving support and giving support were also asked for friends and church members. These variables were combined in the same manner as those for extended family. The resulting measures of reciprocal support with friends and reciprocal support with church members similarly had 4 response categories: 1) Both Give and Receive Support, 2) Only Receive Support, 3) Only Give Support, or 4) Neither Receive or Give Support.

Independent Variables

Two support network characteristics—frequency of contact with network members and subjective closeness to network members—are used as independent variables. Frequency of contact with family members is measured by the question: “How often do you see, write or talk on the telephone with family or relatives who do not live with you? Would you say nearly everyday (7), at least once a week (6), a few times a month (5), at least once a month (4), a few times a year (3), hardly ever (2) or never (1)?” Degree of subjective closeness to family is measured by the question: “How close do you feel towards your family members? Would you say very close (4), fairly close (3), not too close (2) or not close at all (1)?” The same question formats for frequency of contact and subjective closeness were used for friends and church members. Higher values on these items indicate higher levels of contact and closeness to network members. With regard to the church support items, given that some minimal level of service attendance is necessary to establish social ties and assistance, respondents who attended religious services less than once a year were not asked the church support items. This practice is consistent with other research in this area (Krause, 2006) and reflects a general practice in survey research. Eighteen percent of African Americans (18.2%) indicated that they attended religious services less than once per year and are excluded from the analysis for church support.

Sociodemographic variables include age, gender, family income, education, marital status, and parental status. Missing data for household income was imputed for 773 cases (12.7% of the NSAL sample) and missing data for education was imputed for 74 cases. Imputations were completed using an iterative regression-based multiple imputation approach incorporating information about age, gender, region, race, employment status, marital status, home ownership, and nativity of household residents. The distribution for all of the dependent and independent variables is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample and Distribution of Study Variables

| % | N | Mean | S.D. | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 56.93 | 2175 | |||

| Male | 43.07 | 1157 | |||

| Age | 3332 | 41.60 | 14.27 | 18–93 | |

| Family Income | 3332 | 36584.39 | 33481.72 | 0–520000 | |

| Education | 3332 | 12.43 | 2.19 | 0–17 | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 40.81 | 1122 | |||

| Non-married | 59.19 | 2210 | |||

| Parental Status | |||||

| Parent | 81.42 | 2778 | |||

| Non-Parent | 18.58 | 554 | |||

| Family Contact | 3332 | 6.07 | 1.17 | 1–7 | |

| Family Closeness | 3332 | 3.64 | 0.58 | 1–4 | |

| Friend Contact | 3476 | 5.74 | 1.62 | 1–7 | |

| Friend Closeness | 3472 | 3.29 | 0.77 | 1–4 | |

| Congregational Contact | 2990 | 3.75 | 1.82 | 1–6 | |

| Congregational Closeness | 2982 | 3.02 | 0.94 | 1–4 | |

| Patterns of Reciprocal Support with Family | |||||

| Both Gave and Received | 87.42 | 2915 | |||

| Received Support Only | 0.71 | 28 | |||

| Gave Support Only | 9.94 | 319 | |||

| Neither Gave nor Received Support | 1.93 | 70 | |||

| Patterns of Reciprocal Support with Friends | |||||

| Both Gave and Received | 82.61 | 2684 | |||

| Received Support Only | 0.68 | 22 | |||

| Gave Support Only | 8.25 | 268 | |||

| Neither Gave nor Received Support | 8.46 | 275 | |||

| Patterns of Reciprocal Support with Congregation Members |

|||||

| Both Gave and Received | 69.86 | 1611 | |||

| Received Support Only | 3.12 | 72 | |||

| Gave Support Only | 13.18 | 304 | |||

| Neither Gave nor Received Support | 13.83 | 319 |

Percents and N are presented for categorical variables and Means and Standard Deviations are presented for continuous variables. Percentages are weighted and frequencies are un-weighted.

Analysis Strategy

Multinomial logistic regression (Agresti, 1990) was used to analyze the data. Multinomial logistic regression is appropriate for the four-level polytomous response dependent variable used in this study (i.e., reciprocal support) and can accommodate both continuous and categorical independent variables. The reference category is “Both never receiving support and never giving support to extended family members.”

The format and interpretation of multinomial logistic regression is similar to dummy variable regression and consists of contrasts between a comparison and an excluded category. However, in multinomial logistic regression, comparisons between selected categories and the excluded category involve the dependent variable (as opposed to only independent variables in standard dummy variable regression). Specifically, the results focus on contrasts involving: 1) Both Give and Receive Support vs. Neither Give nor Receive, 2) Receive Support Only vs. Neither Give nor Receive, and 3) Give Support Only vs. Neither Give nor Receive).

Two sets of multinomial logistic regressions are presented. The first set includes age, gender, education, income, marital status, and parental status. The second set of regressions adds the two network variables (subjective closeness and frequency of contact). Based upon previous research, we also tested for an interaction between age and parental status (Age × Parent) in all of the regressions (Taylor, 1986). The Age × Parent interaction was significant in the family analysis, but not in analyses for friends or church members; consequently, the interaction term is only included in the family analysis.

Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) and 95% Confidence Intervals are presented with the multinomial logistic regression analyses. The analyses were conducted using SAS 9.13, which uses the Taylor expansion approximation technique for calculating the complex design-based estimates of variance. To obtain results that are generalizable to the African American population, all of the analyses utilize analytic weights. All statistical analyses accounted for the complex multistage clustered design of the NSAL sample, unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and poststratification to calculate weighted, national representative population estimates and standard errors. All percentages reported are weighted.

Results

The percentage distribution of the dependent variables is presented in Table 1. Eighty seven percent of respondents report both receiving and providing support from family. The comparable percentages for friends are 82.61%, and 69.86% for church members. Roughly 1 out of 10 respondents gave support only to family (9.94%), as well as friends (8.25%) and church members (13.18%). The percentages for neither giving nor receiving support are 1.93% for family, 8.46% for friends, and 13.38% for church based informal support networks. Please note that the percentages for involvement with reciprocal support networks with church members are restricted to respondents who attended religious services at least once a year.

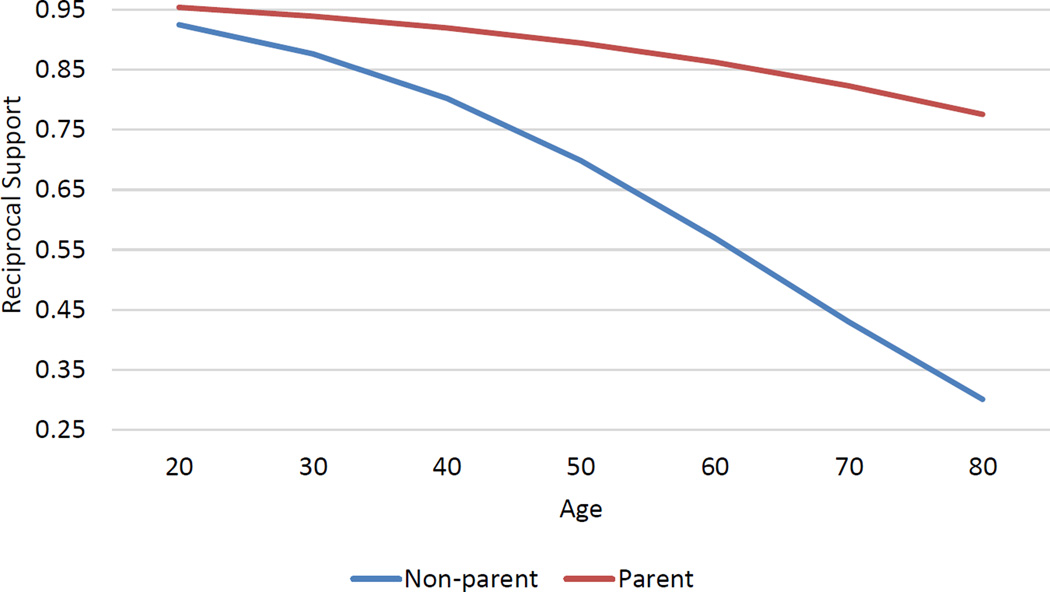

The multinomial regression analyses for reciprocal support with family members are presented in Table 2. This analysis contrasts whether respondents “neither received nor gave support to their families” with: a) those involved in reciprocal relationships (i.e., both gave and received) (Model 1), b) those who received support only (Model 2), and c) those who gave support only) (Model 3). Models 1–3 control for the demographic variables only, whereas Models 4–6 add controls for the two family network variables. Turning first to Model 1, there are five significant relationships in this model. Age, gender, income, parental status and the interaction between age and parental status are all significant. Women and higher income respondents are more likely than their counterparts to indicate that they both gave and received support. Overall, age is negatively associated with both receiving and giving support. With every 10 years increase in age, the probability of indicating both receiving and giving support, relative to neither receiving and giving support, decreases by 48%. For example, 70 year olds are 48% less likely than 60 year olds to indicate that they both received and gave support. There is also a significant interaction between age and parental status (see Figure 1). The parental status findings must be understood in the context of the significant interaction between these two variables. First, for parents and non-parents, age is negatively associated with both receiving and giving support. However, having a child moderates this relationship; that is, for persons who are not parents, older age is associated with a much lower likelihood of involvement in reciprocal support networks with family. For parents, however, the levels of involvement in reciprocal support networks are lower with advancing age, but the rate of decrease is not as steep. For example, as noted in Figure 1 at 60 years of age roughly 85% of African American parents both give and receive support, compared to only 55% of non-parents. Two significant relationships in Model 3 indicate that respondents with higher levels of income and those with higher levels of education are more likely than their counterparts to indicate that they gave support only.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regressions of the Family Network and Demographic Variables on the Patterns of Reciprocal Support among African Americans

| Baseline Models | Models with Family Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | |

| RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | |

| Age | 0.94***(0.92,0.96) | 0.99(0.92,1.06) | 1.00(0.97,1.03) | 0.94***(0.91,0.96) | 0.98(0.92,1.06) | 0.99(0.96,1.02) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.84*(1.06,3.18) | 2.15(0.59,7.77) | 1.24(0.73,2.10) | 1.53(0.86,2.72) | 1.95(0.57,6.63) | 1.15(0.64,2.06) |

| Education | 1.08(0.99,1.18) | 0.98(0.81,1.19) | 1.12*(1.00,1.25) | 1.10*(1.01,1.19) | 1.00(0.83,1.20) | 1.14*(1.03,1.27) |

| Household Income | 1.08*(1.00,1.16) | 0.98(0.86,1.11) | 1.08(1.00,1.16) | 1.06(0.99,1.13) | 0.97(0.86,1.09) | 1.06(0.98,1.13) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.08(0.58,2.02) | 0.42(0.08,2.17) | 1.07(0.56,2.04) | 1.05(0.55,2.03) | 0.42(0.09,2.07) | 1.07(0.56,2.04) |

| Parent | 0.19*(0.04,0.79) | 0.40(0.01,21.14) | 0.56(0.10,3.09) | 0.22(0.04,1.29) | 0.40(0.07,21.99) | 0.60(0.08,4.23) |

| Age × Parent | 1.04**(1.02,1.07) | 1.01(0.94,1.08) | 1.02(0.99,1.05) | 1.04*(1.00,1.07) | 1.01(0.94,1.08) | 1.01(0.98,1.05) |

| Family Contact | -- | -- | -- | 1.58*** (1.35,1.85) | 1.19(0.87,1.64) | 1.30**(1.11,1.53) |

| Family Closeness | -- | -- | -- | 2.89***(2.20,3.79) | 1.39(0.81,2.38) | 1.47**(1.14,1.91) |

| F | 7.22 | 13 | ||||

| df | 34 | 34 | ||||

| N | 3333 | 3332 | ||||

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

Comparison group for each model is ‘Never Receive Support and Never Give Support to Extended Family Members’

RRR=Relative Risk Ratio

CI=Confidence Interval

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of reciprocal support with extended family members by parental status and age among African Americans.

Models 4–6 include family contact and family closeness. In Model 4 (Both Gave and Received Support), age and the age × parental status interaction remain significant. Education is positively associated with both giving and receiving support, as is subjective family closeness and frequency of contact with extended family members. An examination of the relative risk ratios in Model 6 (Gave Support Only), reveals that education, subjective family closeness and frequency of contact are also positively associated with giving support only.

The analysis of reciprocal support with friends is presented in Table 3. In the baseline Model 1 (Both Gave and Received Support), education and income are positively associated with both receiving and providing support with friends. Married respondents are less likely than unmarried respondents to both receive and provide support with friends (Model 1). After controlling for friendship contact and friendship closeness (Model 4), all three of these variables are no longer significant. Age, however, became significant for both receiving and providing support when friendship contact and friendship closeness are controlled (Model 4). Income is negatively associated with receiving support from friends (Received Support Only), even after the friendship network variables (contact and closeness) are controlled. In addition, the confidence interval for this relationship is very small (CI=0.70, 0.94) indicating that this relationship is stable despite the fact that there are very few respondents who indicate they only receive help from friends. Lastly, friendship contact and closeness are positively associated with the friendship support variables, the one exception being the lack of a relationship between friend contact and Received Support Only (Model 5).

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regressions of the Friendship Network and Demographic Variables on the Patterns of Reciprocal Support with Friends among African Americans

| Baseline Models | Models with Friendship Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | |

| RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | |

| Age | 0.99(0.98,1.01) | 1.01(0.98,1.05) | 1.00(0.98,1.01) | 0.98**(0.97,0.99) | 1.01(0.97,1.04) | 0.99(0.97,1.01) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.06(0.73,1.54) | 0.81(0.28,2.39) | 1.49(0.84,2.64) | 0.80(0.54,1.20) | 0.75(0.26,2.11) | 1.33(0.77,2.29) |

| Education | 1.07*(1.00,1.14) | 0.97(0.83,1.12) | 0.99(0.92,1.07) | 1.02(0.97,1.08) | .95(0.82,1.09) | 0.97(0.90,1.05) |

| Household Income | 1.04*(1.00,1.07) | 0.81**(0.70,0.94) | 0.99(0.94,1.05) | 1.02(0.99,1.05) | 0.81**(0.70,0.94) | 0.98(0.93,1.03) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 0.61*(0.41,0.91) | 1.16(0.38,3.51) | 0.92(0.52,1.63) | 0.70(0.46,1.08) | 1.21(0.41,3.55) | 0.96(0.55,1.68) |

| Parent | 0.57(0.31,1.05) | UN | 0.77(0.38,1.54) | 0.66(0.37,1.15) | UN | 0.77(0.41,1.43) |

| Friend Contact | -- -- | -- -- | -- -- | 1.59***(1.44,1.76) | 1.12(0.83,1.52) | 1.16*(1.02,1.33) |

| Friend Closeness | -- -- | -- -- | -- -- | 3.69***(2.81,4.83) | 2.31*(1.18,4.53) | 1.84**(1.28,2.67) |

| F | 197.72 | 189.13 | ||||

| df | 34 | 34 | ||||

| N | 3239 | 3236 | ||||

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

Comparison group for each model is ‘Never Receive Support and Never Give Support to Friends’

RRR=Relative Risk Ratio

CI=Confidence Interval

UN=Unstable due to the small n in this category.

Table 4 presents the analysis for support with church members. Both the baseline and full models indicate significant age, education and income differences. Age and income are positively associated with giving support only (Model 3), whereas education is negatively associated with receiving support only (Model 2). Frequency of contact and subjective closeness with church members are positively associated with both giving and receiving support (Model 4) and giving support only (Model 6). Finally, subjective closeness to church members is also related to receiving support only (Model 5), while frequency of contact with church members is not.

Table 4.

Multinomial Logistic Regressions of the Church-Based Network and Demographic Variables on the Patterns of Reciprocal Support with Church Members among African Americans

| Baseline Models | Models with Church Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | |

| RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | RRR(95% C.I.) | |

| Age | 1.02**(1.01,1.03) | 1.00(0.98,1.02) | 1.02***(1.01,1.04) | 1.00(0.99,1.01) | 0.99(0.97,1.02) | 1.02*(1.00,1.03) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.12(0.81,1.54) | 1.64(0.76,3.53) | 0.98(0.55,1.73) | 0.81(0.52,1.28) | 1.51(0.64,3.55) | 0.85(0.45,1.62) |

| Education | 0.97(0.90,1.03) | 0.84**(0.75,0.94) | 0.97(0.90,1.04) | 1.04(0.95,1.14) | 0.88*(0.78,0.99) | 1.03(0.94,1.12) |

| Household Income | 1.04(1.00,1.08) | 0.95(0.85,1.06) | 1.05*(1.00,1.10) | 1.03(0.98,1.09) | 0.94(0.84,1.06) | 1.05(0.99,1.11) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 0.99(0.65,1.50) | 1.24(0.53,2.90) | 0.92(0.55,1.52) | 0.75(0.45,1.25) | 1.07(0.45,2.52) | 0.73(0.42,1.27) |

| Parent | 0.69(0.42,1.13) | 0.45(0.18,1.16) | 1.31(0.62,2.75) | 0.71(0.40,1.28) | 0.43(0.17,1.11) | 1.39(0.62,3.14) |

| Church Member Contact | -- | -- | -- | 1.58***(1.37,1.82) | 1.13(0.88,1.45) | 1.26**(1.07,1.47) |

| Church Member Closeness | -- | -- | -- | 4.65***(3.83,5.64) | 2.20***(1.50,3.20) | 2.73***(2.15,3.47) |

| F | 5.11 | 17.16 | ||||

| df | 34 | 34 | ||||

| N | 2291 | 2287 | ||||

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

Comparison group for each model is ‘Never Receive Support and Never Give Support to Congregation Members’

RRR=Relative Risk Ratio

CI=Confidence Interval

In order to facilitate our understanding of the multivariate findings we present all of the significant associations into one table (Table 5). This table reveals that the network variables (subjective closeness and frequency of contact) were consistently and positively associated with receiving and giving support, as well as giving support only. However, there were no consistent associations for the demographic variables across family, friend and church member networks.

Table 5.

| Baseline Models | Models with Network Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only |

Both Gave and Received Support |

Received Support Only |

Gave Support Only | |

| Age | −FAM, CH | CH | −FAM, −FR | CH | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | FAM | |||||

| Education | FR | −CH | FAM | FAM | −CH | FAM |

| Household Income | FR | −FR | CH | −FR | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | −FR | |||||

| Parent | −FAM | |||||

| Age × Parent | FAM | FAM | ||||

| Network Closeness | -- | -- | -- | FAM, FR, CH | FAM, FR, CH | |

| Network Contact | -- | -- | -- | FAM, FR, CH | CH | FAM, FR, CH |

All noted relationships significant to at least

p<.05

FAM=Family, FR=Friends and CH=Church

Negative sign (−) indicates a negative relationship (e.g., −FAM), no sign indicates a positive relationship (e.g., FAM)

Comparison group for each model is ‘Never Receive Support and Never Give Support’

Discussion

The discussion section begins with presentation of overall findings, followed by discussion of specific findings for family, friend and church networks. Our findings indicate that African Americans are very involved in reciprocal support networks with their extended family, friends and church members. Respondents were most extensively involved in reciprocal supports with extended family members, followed closely by friends and then church networks. Eight out 10 respondents indicated that they are involved in reciprocal support exchanges where they both gave and received support with their extended family members and their friends. Only a few respondents were totally isolated from their support networks indicating that they neither received nor gave support. Roughly 2% of respondents indicated that they neither provided nor received assistance from their extended family, while 8% did not give or provide support to friends. This is consistent with other research indicating that in comparison to Whites, African Americans are more involved with kinship networks than friendship networks (Ajrouch, Antonucci, & Janevic, 2001; Taylor et al., 2013). Our findings also indicated respondents were more involved with family and friend networks than with church support networks (14% indicated neither receiving nor giving support to church members). This is in addition to the roughly 1 in 6 African Americans who rarely or never attends religious services [although the rates of attending religious services is much higher for African Americans than Whites (Brown, Taylor, & Chatters, 2013)]. However, the importance of informal support from church members should not be underestimated as it is associated better physical health (Krause, 2008), lower rates of depression (Chatters et al., 2015), and is a protective factor for suicidal behaviors (Chatters, Taylor, Lincoln, Nguyen, & Joe, 2011).

Family Networks

Our findings clearly indicate that African Americans are heavily involved in their family support networks. These findings are consistent with both classical (Hill, 1972) and more contemporaneous research (Lincoln et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2013) indicating that the vast majority of African Americans are involved in reciprocal extended family support networks. In regards to demographic correlates, older respondents were less likely than their younger counterparts to report being involved with a reciprocal support network. This relationship was moderated by being a parent; that is, the relationship between age and reciprocal support was conditioned by parental status.

Older adults with an adult child were more likely to both give and receive support in comparison to those older adults who were childless. This finding is consistent with previous research on African Americans which shows that older adults with children are more likely to receive support from their extended families (Taylor, 1986) and have larger networks of family members to seek help from during a health crisis (Chatters, Taylor & Jackson, 1985, 1986). Further, this finding is consistent with a host of work in the Gerontological literature documenting the importance of having an adult children for receiving support and for providing caregiving to older parents (Bengtson et al., 2002; Kahn et al., 2011).

The findings of this study in conjunction with previous research indicate that African American childless elderly are in a particularly disadvantaged position. For those with children, their children are the linkages to their family networks and can inform other family and non-kin support network members about the well-being of their older parent. Childless older adults, on the other hand, may be at risk of becoming isolated from family members. This is partially due to the fact that family members who are their age peers may have passed away. Other family members will mostly be younger than themselves and they may not know them as well. Without an adult child to help maintain these linkages, older adults have a high likelihood of not receiving support and potentially becoming socially isolated from their family members.

Gender was significant in the baseline model for receiving and giving support, indicating that women were more likely than men to be involved in reciprocal support relationships with extended family members. However, gender’s effect was attenuated with the introduction of family network variables (contact and closeness). Prior research on gender differences in support networks indicates that women are more involved and in contact with extended family networks than men, which provides them the awareness and opportunity to be more involved in family support networks. Further, recent work on specific types of family support networks (Taylor, Forsythe-Brown, Taylor, & Chatters, 2014) indicates that African American women are less likely to belong to family networks that are estranged and more likely to belong to optimal family networks even when differences in family contact are taken into account. Similarly, African American women are more likely to receive emotional support from extended family members after controlling for family contact and family closeness (Lincoln et al., 2013). Other research on non-Hispanic Whites identifies gender as the most consistent correlate of social support provision, with women being more likely to provide emotional support to others (Kahn, McGill, & Bianchi, 2011; Liang, Krause, & Bennett, 2001; Plickert, Cote, & Wellman, 2007), exchange emotional support with others (Liebler & Sandefur, 2002; Plickert et al., 2007) and provide support to elderly parents (Kahn et al., 2011). These collective findings indicate that women play a greater role in family networks and derive significant benefit from their involvement with respect to reciprocal support relationships.

Several socio-economic status differences emerged for reciprocal support, as well as giving support only. In baseline models, income was positively associated with reciprocal support and providing support only, while education was significantly associated with providing support to others. Although education was not related to reciprocal support in the baseline model, it was a significant predictor of reciprocal support after adjusting for family contact and closeness (Table 2: Model 6). These findings are consistent with the work of Krause (1992) who found that higher education increased the provision of support. In contrast, previous research among African Americans indicates few socio-economic status differences in either the receipt or provision of social support. For instance, Lincoln et al.’s study (2013) failed to find any socioeconomic status differences for receiving emotional support from extended family members. However, a study of older adults in Brooklyn, NY (Fiori et al., 2008) found a positive relationship between income and the likelihood of engaging in instrumental reciprocal support with extended family among older African Americans.

Friendship Networks

Education, income and marital status were significantly associated with both providing and receiving support in the baseline models. Consistent with previous research (Chatters, Taylor, & Jackson, 1986) which found that unmarried African Americans were much more likely than married persons to rely on friends than family when dealing with a health problem, in the present study married respondents were less likely to both give and receive support from friends. Income and education were positively associated with both giving and receiving support from friends. Despite limited research on African American friendships, these findings are consistent with research on Whites indicating that socioeconomic status is positively associated with involvement in friendship networks (Miche, Huxhold, & Stevens, 2013). Lastly, respondents with lower incomes were more likely than those with higher incomes to report that they only received support from friends. This is an interesting finding and it indicates that those who are extremely economically vulnerable are able to rely upon friends for assistance. Prior ethnographic research amply demonstrates the role of friends and fictive kin in the support networks of poor African Americans (Stack, 1975).

Church Networks

Two notable findings for church support indicate that, in both baseline and adjusted models, education was negatively associated with receiving support only. This finding is unique because research generally finds that, among African Americans, education is positively associated with religious service attendance and participation in church activities (Taylor, Chatters, & Brown, 2014). The income finding is, however, consistent with the stated mission of religious organizations to help and provide assistance for their lower socio-economic status members. The second notable finding is that age is positively associated with providing support only (in baseline and adjusted models). This is consistent with research that notes that age is positively associated with service attendance and participation in church activities (Taylor, Chatters, et al., 2014). Participation in these activities provides the opportunity to bond with fellow congregants and opportunities to provide assistance. Additionally, older men and women provide a fair amount of volunteer work including cooking meals and providing cleaning and other services for ill church members. Interestingly, a previous significant association between age and reciprocal support in our analysis was not maintained after the addition of contact with and closeness to church members.

Family, Friend, and Church Based Reciprocal Support Networks

The patterns of findings for demographic and network (i.e., contact and closeness) variables across family, friend and church networks are interesting in what they suggest about the nature of support exchanges that are specific to each group. First, the demographic variables were not consistently associated with involvement in reciprocal support across the three networks. As noted earlier, the age × parent interaction was only significant with regards to family networks. Similarly, age was associated with giving support only in church networks, but not the other two networks. Collectively, the inconsistency of findings for the demographic variables across the three support networks should be expected and indicate that these networks are not identical and that each has important strengths and limitations in regards to involvement in support exchanges and the broader social context in which exchanges occur.

Recall that social exchange theory suggests that individuals seek to maximize benefits from social relationships and assess the likelihood of achieving maximum gains and minimal losses by conducting a cost/benefit analysis (Becker, 1974; Homans, 1958). Part of this assessment process necessarily involves an understanding of the prior relationships and normative expectations that exist within each particular network (e.g., family, church). For example, family networks and relationships are commonly construed as both the most enduring of our social connections and possessing a unique set of expectations and obligations (i.e., filial piety). As such, demographic factors such as age, gender and parenthood are not simply status markers, but also situate individuals in relation to others and a set of normative expectations and behaviors. Age, gender and parental status were all significant for reciprocal support relationships (both give and receive support) with family networks, even taking into account family contact and closeness. Findings for gender in which women were more likely than men to be involved in reciprocal support exchanges are consistent with the primacy of women in relation to support relationships within families. Age differences indicate that older persons are less likely to be involved in reciprocal exchanges with family. However, parental status makes a difference such that older persons with children, as compared to childless elderly, are more likely to both give and receive support with family. In terms of resource measures, higher levels of education were associated with reciprocal support, as well as providing support only to family.

Social exchange theory furthermore embodies a distinctive focus on the individual’s assessment of costs and benefits. Given this, the theory understates social actors’ understanding of how their behaviors as a support participant may result in losses and gains that impact others and the social network as a whole. That is to say, in particular circumstances and settings, individuals may act in ways that maximize benefits for others for the network as a whole rather than for themselves and, in doing so, incur costs (time, effort, resources) to self. Social relationships and support expectations and obligations within religious organizations are grounded in ideals of altruism and providing for those in need, communal service to the church, and mutuality in supportive relationships with others (Krause, 2008). In this study, although receiving support only from church members was infrequent, it was more likely to be reported by persons with lower levels of education. With regard to age, the finding that older age was associated with participating in reciprocal support exchanges is consistent with religious injunctions and obligations to provide for the elderly who have higher physical, material and social needs. In this analysis, older adults’ higher levels of reciprocal support and giving support to others is a likely reflection of their heightened religious identifies and greater overall investment in religious practices and relationships as compared to younger groups (Taylor et al., 2004). Within the context of church networks, acting in supportive ways to others accrues intangible or spiritual benefits (i.e., acting in accordance with one’s faith and religious ideals), as well as social benefits (i.e., group recognition as a moral and compassionate individual). Further, because older adults presumably have a longer history of involvement within their churches, they have long standing relationships within the church and have accrued a number of mutual obligations over time.

Across all three networks, both network variables (i.e., contact and closeness) were significantly associated with receiving support and giving support, as well as giving support only. That is, individuals who were subjectively closer to their family, friends and church members and those who interacted more frequently with these groups were more likely to both give help only and both give and receive support with these networks. These findings are consistent with previous research among African Americans (Lincoln et al., 2013) and non-Hispanic Whites (Antonucci et al., 1990) demonstrating the importance of family affection and family interaction for maintaining family ties and being involved in family support networks. Further, although research on church-based support networks is more limited, present findings are consistent with evidence about the importance of contact and closeness for support from church members (Nguyen, Taylor, & Chatters, in press; Taylor, Lincoln, & Chatters, 2005).

Limitations and Conclusion

Our paper has several limitations that should be noted. Causal inferences are problematic with cross-sectional data and longitudinal data are preferred. It is important to note that there may be some overlap in the three informal support networks that we examined. This may be particularly true with regards to friendship and church based networks. However, qualitative research in this area has shown that despite the potential overlap in networks, African Americans can clearly differentiate the support that they receive from family, friends and church members (Taylor et al., 2004). Finally, it’s important to note that for the analysis of received support only, there were fewer significant demographic and social network associations. This is mainly due to the fact that so few respondents reported that they received support only from family, friend and church networks. Consequently, there was very limited variation among respondents who received support only. The vast majority of respondents reported that they both give and receive support from their social networks.

Our findings reveal that African Americans are involved in support exchanges within kin and non-kin networks. Consistent with frameworks that emphasize the importance of balance in supportive relationships (Boerner & Reinhardt, 2003; Gleason et al., 2003; Keyes, 2002), the vast majority of respondents reported engaging in reciprocal exchanges as both providers and recipients of support with members of their networks. Although not directly comparable to Ingersoll-Dayton et al.’s (1988) findings regarding differences in the likelihood of reciprocal relationships, respondents were slightly more involved in reciprocal support relationships with family networks rather than friendship or church-based networks, clearly underscoring the primacy of filial bonds. However, support exchanges involving friends and church members were also apparent. Further, level of contact and feelings of closeness were predictive of support across all three social networks and emphasized the importance of investments and personal connections for garnering benefits from these networks.

This study complements previous work on the complementary roles of family, friend and church support networks (Taylor & Chatters, 1986), as well as studies of racial differences in support networks (Taylor et al., 2013). It is important to note that our findings are limited by the fact that we examine global measures of support in contrast to more discrete measures of instrumental (financial, transportation), emotional support, or support provided in response to a specific event or crisis. Findings may be different using more discrete measures of support. Despite this limitation, this is only one of very few analyses of the correlates of reciprocal support and, to our knowledge, this is the first analysis of reciprocal support networks based on a national sample of African Americans.

Contributor Information

Robert Joseph Taylor, School of Social Work, University of Michigan

Dawne M. Mouzon, Rutgers University

Ann W. Nguyen, University of Southern California

Linda M. Chatters, School of Public Health, School of Social Work, University of Michigan

References

- AAPOR. Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 4th. Lenexa, KS: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch KJ, Antonucci TC, Janevic MR. Social networks among blacks and whites the interaction between race and age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56(2):S112–S118. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.s112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Fuhrer R, Jackson J. Social support and reciprocity: A cross-ethnic and cross-national perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. Theory of social interactions. The Journal of Political Economy. 1974;82(6):1063–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Giarrusso R, Mabry JB, Silverstein M. Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: Complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(3):568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Reinhardt JP. Giving while in need: Support provided by disabled older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58(5):S297–S304. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.s297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RK, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Religious non-involvement among African Americans, Black Caribbeans and non-hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Review of Religious Research. 2013;55(3):435–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Size and composition of the informal helper networks of elderly Blacks. Journal of Gerontology. 1985;40(5):605–614. doi: 10.1093/geronj/40.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Aged blacks' choices for an informal helper network. Journal of Gerontology. 1986;41(1):94–100. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Nguyen A, Joe S. Church-based social support and suicidality among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Arch Suicide Res. 2011;15(4):337–353. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2011.615703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Schroepfer T. Patterns of informal support from family and church members among African Americans. Journal of Black Studies. 2002;33(1):66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Nicklett EJ. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(6):559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Consedine NS, Magai C. Ethnic differences in patterns of social exchange among older adults: The role of resource context. Ageing and Society. 2008;28(04):495–524. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MEJ, Iida M, Bolger N, Shrout PE. Daily supportive equity in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29(8):1036–1045. doi: 10.1177/0146167203253473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ML, Amodeo M, Clay C, Fassler I, Ellis MA. Racial differences in social support: Kin versus friends. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(3):374–380. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RB. The strengths of Black families. New York: University Press of America; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Eggebeen DJ, Clogg CC. The structure of intergenerational exchanges in American families. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;98(6):1428–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Homans GC. Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology. 1958;63(6):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Antonucci TC. Reciprocal and Nonreciprocal Social Support: Contrasting Sides of Intimate Relationships. Journal of Gerontology. 1988;43(3):S65–S73. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.3.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, Williams DR. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International journal of methods in psychiatric research. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR, McGill BS, Bianchi SM. Help to family and friends: Are there gender differences at older ages? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(1):77–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL. The exchange of emotional support with age and its relationship with emotional well-being by age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(6):P518–P525. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Stress, religiosity, and psychological well-being among older blacks. J Aging Health. 1992;4(3):412–439. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and mortality. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(3):S140–S146. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DS, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Himle JA. Family and friendship informal support networks and social anxiety disorder among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(7):1121–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Krause N, Bennett JM. Social exchange and well-being: Is giving better than receiving? Psychology and Aging. 2001;16(3):511–523. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebler CA, Sandefur GD. Gender differences in the exchange of social support with friends, neighbors, and co-workers at midlife. Social Science Research. 2002;31(3):364–391. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Correlates of emotional support and negative interaction among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Journal of Family Issues. 2013;34(9):1262–1290. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12454655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among black Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(12):1947–1958. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0512-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miche M, Huxhold O, Stevens NL. A latent class analysis of friendship network types and their predictors in the second half of life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;68(4):644–652. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, et al. Church-based social support among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research. doi: 10.1007/s13644-016-0253-6. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien RL. Depleting capital? Race, wealth and informal financial assistance. Social Forces. 2012;91(2):375–396. [Google Scholar]

- Plickert G, Cote RR, Wellman B. It's not who you know, it's how you know them: Who exchanges what with whom? Social networks. 2007;29(3):405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian N, Gerstel N. Kin support among Blacks and Whites: Race and family organization. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(6):812–837. [Google Scholar]

- Stack C. All our kin: Strategies for survival in a black community. New York: Basic Books; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ. Receipt of Support from Family among Black Americans: Demographic and Familial Differences. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1986;48(1):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM. Extended family and friendship support networks are both protective and risk factors for major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms among African-Americans and Black Caribbeans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(2):132–140. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church-based informal support among elderly blacks. The Gerontologist. 1986;26(6):637–642. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Brown RK. African American religious participation. Review of Religious Research. 2014;56(4):513–538. doi: 10.1007/s13644-013-0144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Woodward AT, Brown E. Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin, and congregational informal support networks. Family Relations. 2013;62(4):609–624. doi: 10.1111/fare.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Forsythe-Brown I, Taylor HO, Chatters LM. Patterns of emotional social support and negative interactions among African American and black Caribbean extended families. Journal of African American Studies. 2014;18(2):147–163. doi: 10.1007/s12111-013-9258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM. Supportive relationships with church members among African Americans. Family Relations. 2005;54(4):501–511. [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Harrison SC. Keeping in touch: How women in mid-life allocate social contacts among kith and kin. Social Forces. 1992;70(3):637–654. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AT, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Neighbors HW, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. The use of professional and informal support by African Americans and Caribbean blacks with mental disorders. Psychiatric Service. 2008;59(11):1292–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]