Abstract

BACKGROUND

We examined racial/ethnic disparities in school-based behavioral health service use for children with psychiatric disorders.

METHODS

Medicaid claims data were used to compare the behavioral healthcare service use of 23,601 children aged 5–17 years by psychiatric disorder (autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct/oppositional defiant disorder, and “other”) and by race/ethnicity (African-American, Hispanic, white, and other). Logistic and generalized linear regression analyses were used.

RESULTS

Differences in service use by racial/ethnic group were identified within and across diagnostic groups, both for in-school service use and out-of-school service use. For all disorders, Hispanic children had significantly lower use of in-school services than white children. Among children with ADHD, African-American children were less likely to receive in-school services than white children; however, there were no differences in adjusted annual mean Medicaid expenditures for in-school services by race/ethnicity or psychiatric disorders. Statistically significant differences by race/ethnicity were found for out-of-school service use for children with ADHD and other psychiatric disorders. There were significant differences by race/ethnicity in out-of-school service use for each diagnostic group.

CONCLUSIONS

Differences in the use of school-based behavioral health services by racial and ethnic groups suggest the need for culturally appropriate outreach and tailoring of services to improve service utilization.

Keywords: Medicaid, behavioral health, mental health, school-based health services, health disparity

How race/ethnicity affects school-based behavioral health service use is poorly understood.1–5 Many minority youth with psychiatric disorders do not receive needed behavioral health services, perhaps because of their and their families’ interpretation of symptoms, beliefs about the most appropriate responses, and poor access to specialty care.1, 6–10 One way to improve access and reduce racial/ethnic disparities in service use is to provide behavioral health services in schools.6 Public schools have become the main provider of behavioral health services to children in the United States (US) and are responsible for approximately 70–80% of all behavioral health services delivered to children.11–14 Schools provide convenient access to behavioral health services and significantly reduce barriers to treatment seen in traditional outpatient settings, particularly in ethnic minority groups15–17

The increase in schools’ provision of behavioral health services resulted from new education policies mandating that supports be given to children with psychiatric disorders,18 new federal funding initiatives,19 and that disparities in service use based on socio-economic status, race, and ethnicity must be eliminated.12 Currently, 32 states leverage Medicaid funds to provide school-based services. Despite an improved policy environment and increased funding, some research indicates that approximately half of children with developmental conditions (autism, developmental delay and intellectual disability) lack easy access to school-based services, and 17% do not have an individualized education plan.20

While school-based services hold promise for decreasing racial/ethnic disparities by improving access, there has been little comparison of service use by racial/ethnic group between school-based services and more traditional outpatient behavioral health services. More importantly, while many studies have demonstrated racial/ethnic disparities in access, diagnosis, and outcomes in youth with various psychiatric disorders,5–7, 21 none, to our knowledge, has directly compared racial/ethnic disparities by psychiatric diagnosis between school-based and other behavioral health services. Understanding how disparities in school-based behavioral health service use differ across race/ethnicity and psychiatric disorders will potentially point to the ways in which schools may differentiate care to address unmet behavioral health needs. It may be that for some disorders, providing school-based behavioral health services increases access to behavioral health services for children who otherwise would not receive care. If racial/ethnic disparities are similar across disorders, it suggests the need for global interventions to reduce them. However, if racial/ethnic disparities differ by disorder, it may suggest the need for more targeted strategies to determine why they exist and how to address them. The purpose of this study was to compare in-school and out-of-school behavioral health service use and associated Medicaid expenditures among ethnic minority children with different psychiatric disorders. All students were from the same school district, were Medicaid enrolled and had equal access to behavioral health services at their schools leveraged through Medicaid.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Sample

The study sample included 23,601 Medicaid-enrolled children between 5–17 years of age who used behavioral health services between October 1, 2008 and September 30, 2009. Medicaid claims data were used. The sample represents the entire population of Medicaid-enrolled youth in Philadelphia who used behavioral health services.

Variables

Psychiatric disorder was defined as having a diagnosis in the Medicaid claims of autism, conduct disorder/oppositional defiant disorder (conduct/ODD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or a different disorder (other psychiatric disorders). Diagnoses were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (9th ed., ICD-9). Children with 2 or more Medicaid claims that indicated primary diagnosis of: (1) 299.xx were identified as having autism; (2) 312.xx or 313.xx were identified as having conduct/ODD; and (3) 314.xx were identified as having ADHD. Other psychiatric disorders included affective mood disorder, substance abuse, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric diagnoses. We focused on these disorders because: (1) most children served through the public mental health system are diagnosed with either ADHD or disruptive behavior disorders;22 and (2) autism is the developmental disorder with the most rapidly increasing prevalence, is expensive to treat, and often requires care in school.23 Less than 5% of study participants had more than one diagnosis. Consistent with previous studies, children who met study criteria for more than one diagnosis were classified in the hierarchy of autism, ADHD, conduct/ODD and other psychiatric disorders.23

In-school behavioral health service use was defined as receiving in-school individual behavioral services (one-on-one behavioral support) during the school day. Out-of-school behavioral services were defined as receiving outpatient treatment in a specialty mental health setting or out-of-school Behavioral Health Rehabilitation Services (BHRS). BHRS is Pennsylvania’s version of wraparound services, designed to provide therapeutic intervention to children aged 3–21 years with serious emotional disturbance, social, or behavioral problems in the least restrictive environment maintaining the child in his/her natural setting.24 Both in-school behavioral health services and out-of-school BHRS require the same level of clinical necessity, which is more intensive care than outpatient care.24 Children who are Medicaid beneficiaries and meet clinical necessity through psychiatric evaluation have equal access to both types of services. Our definition of non-school services did not include acute services such as crisis center visits and inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and restrictive care such as psychiatric residential treatment. Unadjusted and adjusted mean Medicaid expenditures for each type of service were calculated for each race/ethnic group by psychiatric disorder. Demographic variables included sex (male vs. female) and race/ethnicity (African-American, white, Hispanic including both white and African-American, and other).

Data Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to test for differences in demographic characteristics and behavioral health service use by psychiatric disorder. In-school individual behavioral health service use and out-of-school behavioral health service use were not mutually exclusive. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify children’s in-school and out-of-school behavioral health service use (the dependent variables) by race/ethnicity and psychiatric disorder adjusting for age and sex. Two logistic regression analyses were performed for each type of service use: (1) significant difference test of service use by race/ethnicity within each psychiatric disorder; and 2) significant difference test of service use by race/ethnicity across psychiatric disorders. The 2 models were used to identify if: (1) differences in service use exist by race/ethnicity within each psychiatric disorder group; and (2) within-group differences in service use by race/ethnicity significantly differ across psychiatric disorders.

For the Medicaid expenditures analyses, unadjusted annual mean Medicaid expenditures by race/ethnicity, psychiatric disorder, and service type among users were calculated. Generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and log link function were used to compare differences in the expenditures for in-school and out-of-school behavioral health service use by race/ethnicity and psychiatric disorder, adjusting for age and sex. Two generalized linear regression analyses were performed for Medicaid expenditures for each type of service use testing: (1) significant differences in Medicaid expenditures by race/ethnicity within each psychiatric disorder; and (2) significant differences in Medicaid expenditures by race/ethnicity across psychiatric disorders.

RESULTS

The most common psychiatric diagnosis was ADHD (39.9%); 35.2% were diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders, 21.3% with conduct/ODD, and 3.6% with autism (Table 1). The majority (63.0%) of the sample was male and about half (49.4%) was aged 5–11 years. Sex and race/ethnicity distributions significantly differed by psychiatric disorder. Whereas only 16.0% of children with autism were girls, 33.4% of children with conduct/ODD, 28.1% of children with ADHD and 51.4% of children with other psychiatric disorders were girls. The proportion of African-American children was the highest among children with conduct/ODD (76.1%), followed by other psychiatric disorders (61.3%), autism (51.4%) and ADHD (50.5%). The majority of Hispanic children was diagnosed with ADHD (39.8%), followed by other psychiatric disorders (25.4%), conduct/ODD (16.5%) and autism (15.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Psychiatric Disorder (N = 23,601)

| Characteristics | ASD (N = 884) | Conduct disorder/ODD (N = 5028) |

ADHD (N = 9412) |

Other psychiatric disorders (N = 8317) |

Total (N = 23,601) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||||

| Sex (Chi-square = 1248.45)** | ||||||

| Boys | 84.0 | 66.6 | 71.9 | 48.6 | 63.0 | |

| Girls | 16.0 | 33.4 | 28.1 | 51.4 | 37.0 | |

| Age (Chi-square = 2611.16)* | ||||||

| 5–11 years old | 68.6 | 37.4 | 66.3 | 35.6 | 49.4 | |

| 12–14 years old | 18.4 | 34.1 | 22.7 | 27.3 | 26.6 | |

| 15–17 years old | 13.0 | 28.5 | 10.9 | 37.1 | 24.0 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (Chi-square = 1594.32)** | ||||||

| African American | 51.4 | 76.1 | 50.5 | 61.3 | 59.8 | |

| White | 33.4 | 7.4 | 9.8 | 13.3 | 11.4 | |

| Hispanic | 15.2 | 16.5 | 39.8 | 25.4 | 28.9 | |

Note.

ASD: Autism spectrum disorder, ODD: Oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

p < .01,

p < .001;

significant difference by psychiatric disorder category

In-school and Out-of-school Behavioral Health Service Use

Tables 2 and 3 present significance tests in service use by race/ethnicity within each psychiatric disorder and within-group disparities in service use by race/ethnicity across psychiatric disorders. There were significant differences by race/ethnicity in use of in-school behavioral health services. For each diagnosis group, Hispanic children were less likely to use in-school behavioral health services than White children (Table 2). They were 49% less likely for autism (p = .002); 48% less likely for conduct/ODD (p = .039); 55% less likely for ADHD (p < .001); and 50% less likely for other psychiatric disorders (p = .039). For the ADHD group, African-American children were 62% more likely than white children with ADHD to use in-school individual behavioral health services (p < .001). The lower use of in-school service among Hispanic children compared to white children was similar across all psychiatric disorders. Disparities in in-school service use between African-American and white children were found only for the ADHD group (p = .02).

Table 2.

In-school Individual Behavioral Health Service Use and Associated Medicaid Expenditures by Race/Ethnicity and Psychiatric Disorder

| ASD (N = 434) | Conduct/ODD (N = 253) | ADHD (N = 774) | Other psychiatric disorders (N = 141) | Type III interaction effect test (N = 1683) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Use by Race/Ethnicity |

% of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | % of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | % of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | % of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | p-value |

| African American | 45.3 | 0.84 | 0.62–1.14 | 0.276 | 80.7 | 1.04 | 0.65–1.66 | .879 | 71.7 | 1.62 | 1.25–2.10 | .000 | 73.2 | 1.24 | 0.76–2.04 | .395 | .021 |

| Hispanic | 10.9 | 0.51 | 0.33–0.78 | 0.002 | 8.9 | 0.52 | 0.28–0.97 | .039 | 16.9 | 0.45 | 0.33-0.60 | < .001 | 12.7 | 0.50 | 0.26–0.97 | .039 | .980 |

| White | 32.8 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 8.1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 8.9 | Reference | Reference | 13.4 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

|

Annual Mean Medicaid Expenditures by Race/Ethnicity |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level | |

| African American | $6877 | 1.10 | 0.97–1.25 | 0.142 | $5753 | 0.75 | 0.54–1.03 | .076 | $5141 | 0.99 | 0.82–1.19 | .934 | $5370 | 0.91 | 0.62–1.33 | .623 | .165 |

| Hispanic | $5,523 | 0.97 | 0.80–1.17 | 0.725 | $5845 | 0.73 | 0.48–1.12 | .147 | $4,307 | 0.85 | 0.69–1.06 | .162 | $5684 | 0.95 | 0.57–1.57 | .841 | .685 |

| White | $6,537 | Reference | Reference | Reference | $7405 | Reference | Reference | Reference | $5263 | Reference | Reference | Reference | $5355 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Note.

Ns in the columns present the numbers of service users by psychiatric disorders. 2008/2009 dollar rate presented. ASD: Autism spectrum disorder, ODD: Oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. OR: Odds ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Each row presents a separate model comparing children with all other psychiatric disorder groups to children with ASD. Mean estimates and mean estimate 95% CI present exponentiated beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals of the mean estimates, respectively. Type III interaction effect models tested if within-group differences in service use and Medicaid expenditures by race/ethnicity significantly differ across psychiatric disorders adjusting for sex and age.

Table 3.

Out-of-school Behavioral Health Service Use and Associated Medicaid Expenditures by Race/Ethnicity and Psychiatric Disorder

| ASD (N = 819) | Conduct/ODD (N = 4,503) | ADHD (N = 9,192) | Other psychiatric disorders (N = 8,085) | Type III interaction effect test |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Use by Race/Ethnicity |

% of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | % of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | % of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | % of users |

OR | 95% CI | p-level | p-value |

| African American | 45.8 | 1.08 | 0.47-2.46 | .877 | 73.7 | 0.74 | 0.51-1.09 | .124 | 48.4 | 0.42 | 0.24-0.72 | .002 | 59.3 | 0.66 | 0.44-1.01 | .053 | .315 |

| Hispanic | 14.0 | 8.03 | 0.49-132.74 | .146 | 17.0 | 1.50 | 0.94-2.38 | .089 | 39.3 | 1.91 | 1.02-3.58 | .043 | 25.1 | 1.79 | 1.04-3.08 | .036 | .980 |

| White | 29.9 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 7.4 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 9.6 | Reference | Reference | 13.0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

|

Annual Mean Medicaid Expenditures by Race/Ethnicity |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level |

Median expenditures |

Mean estimate |

Mean estimate 95% CI |

p-level | |

| African American | $3003 | 1.11 | 0.95-1.30 | .209 | $1113 | 1.01 | 0.89-1.14 | .917 | $852 | 1.24 | 1.14-1.35 | <.001 | $600 | 1.10 | 1.02-1.19 | .010 | .032 |

| Hispanic | $1561 | 0.72 | 0.58-0.89 | .003 | $647 | 0.72 | 0.62-0.83 | <.001 | $532 | 0.62 | 0.57-0.68 | <.001 | $486 | 0.72 | 0.66-0.78 | <.001 | .045 |

| White | $2481 | Reference | Reference | Reference | $915 | Reference | Reference | Reference | $586 | Reference | Reference | Reference | $564 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Note.

Ns in the columns present the numbers of service users by psychiatric disorders. 2008/2009 dollar rate presented. ASD: Autism spectrum disorder, ODD: Oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. OR: Odds ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Each row presents a separate model comparing children with all other psychiatric disorder groups to children with ASD. Mean estimates and mean estimate 95% CI present exponentiated beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals of the mean estimates, respectively. Type III interaction effect models tested if within-group differences in service use and Medicaid expenditures by race/ethnicity significantly differ across psychiatric disorders adjusting for sex and age.

The analysis of out-of-school behavioral health service use showed significant differences by race/ethnicity within the ADHD group and the other psychiatric disorders group (Table 3). African-American children with ADHD were 58% less likely than white children with ADHD to use out-of-school behavioral health services (p = 0.002). Hispanic children with ADHD were 91% more likely than white children with ADHD to use out-of-school behavioral health services (p = .043). Hispanic children with other psychiatric disorders were 79% more likely than white children with other psychiatric disorders to use out-of-school behavioral health services (p = .036). The racial/ethnic differences did not differ by psychiatric disorder.

Medicaid Expenditures for In-school and Out-of-school Behavioral Health Service Use

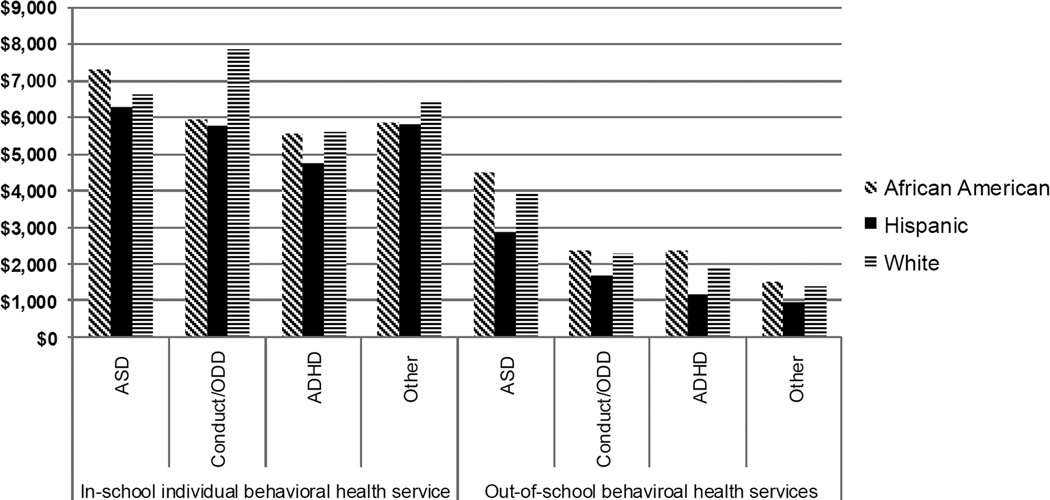

As Figure 1 shows, the unadjusted annual mean Medicaid expenditures for in-school individual behavioral health service use ranged from $4,768 for Hispanic children with ADHD to $7,846 for white children with conduct/ODD. With the exception of children with autism, in-school behavioral health Medicaid expenditures for white children was the highest followed by the expenditures for African-American and Hispanic children. The unadjusted Medicaid expenditures for in-school behavioral health service use by psychiatric disorder was the highest for children with autism, and ranged from $6273 for Hispanic children to $7280 for African-American children. Despite the differences in the unadjusted Medicaid expenditures, the age and sex adjusted mean Medicaid estimates for in-school individual behavioral health service use were not significantly different by race/ethnicity within each psychiatric disorder or across psychiatric disorders.

Figure 1. Annual mean Medicaid expenditures by race, psychiatric disorder and service type among service users.

Note. 2008/2009 dollar rate presented. Unadjusted annual mean Medicaid expenditures among service users are presented in Figure 1. ASD: Autism spectrum disorder, ODD: Oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

As Figure 1 shows, the unadjusted annual mean Medicaid expenditures for out-of-school behavioral service use ranged from $1169 for Hispanic children with ADHD to $4462 for African-American children with autism. The unadjusted Medicaid expenditures for out-of-school behavioral health services were the highest for African-American children for all psychiatric disorder groups, followed by white children and Hispanic children. The adjusted mean Medicaid expenditures for out-of-school behavioral health service use reflected the pattern of unadjusted expenditures by race/ethnicity within and across psychiatric disorder groups; the disparities in service use between Hispanic and white children and between African-American and white children were significantly different by psychiatric disorders. Compared with white children, the adjusted mean Medicaid estimates for out-of-school behavioral health service use for Hispanic children were 0.72 times lower for autism (p = .003), 0.72 times lower for conduct/ODD (p < .001), 0.62 times lower for ADHD (p < .001), and 0.72 times lower for other psychiatric disorders (p < .001). The adjusted mean Medicaid estimates for African-American children with ADHD were 24% higher than those for white children with ADHD (p < .001) and 10% higher for African-American children with other psychiatric disorders compared to white children with other psychiatric disorders (p = .010). The differences in the adjusted mean expenditures between Hispanic and white children and between African-American and white children significantly differed across psychiatric disorder (p = .045 and p = .032, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The observed disparities in use of in-school services are particularly important and have direct implications for improving access to care for ethnic minorities. The results indicated that many Hispanic children with psychiatric disorders were not using in-school behavioral health services. These differences were not observed when comparing expenditures among users, suggesting that once children access in-school behavioral health services, they use a similar amount of service. The literature suggests that there may be important cultural differences among Hispanics in accessing one-to-one school based care.25, 26 Delphin-Rittmon et al27 found that Hispanics reported stigmatizing views about seeking behavioral health services and only used care in crisis situations or as a last resort. Furthermore, studies have shown that Hispanic families may view teachers and school personnel as having a great deal of power and authority over their child’s education and may trust that their children already receive adequate supports in school.28, 29 Research also has shown that Hispanic parents often stress the importance of both behavior and academics within education30 and may assume the educational system is addressing their child’s behavioral needs without the need of additional services. Therefore, Hispanic families may be hesitant to request additional school support services for their children if the school does not indicate a need for these services. Whereas the process of obtaining services may be complicated for both in and out of school services, research suggests that language barriers may likely present some unique challenges for families that are Spanish-speaking only, as applying for services may require both an understanding of legal rights and a mastery of the English language.31 Spanish speaking only families may be at a significant disadvantage, and there is some research that suggests many undocumented families may be fearful of advocating for additional services for their child.32 Culturally responsive efforts to improve the rates at which Hispanic families of children with psychiatric disorders gain initial access and enrollment in school-based behavioral health services are needed in order to reduce this disparity and improve access to care. Schools may need to consider adopting targeted outreach services for Hispanic families who may benefit from school-based behavioral health services.

Additionally, Hispanic children with ADHD and other psychiatric disorders had significantly higher use of out-of-school services than white children with these same diagnoses; however, their associated expenditures were significantly lower than those of white children. This finding suggests that the disparity in out-of-school service use relates to dosage or intensity, as opposed to access as observed for in-school service use.

Unlike Hispanic children, African-American children with ADHD were more likely to use in-school behavioral health services and less likely to use out-of-school services than white children with ADHD. This finding has several potential explanations. First, it is possible that many African-American children with autism are incorrectly diagnosed with ADHD,33 which may inflate the service use observed among children diagnosed with ADHD in this sample. Previous research has demonstrated that children from different racial/ethnic groups are assigned psychiatric diagnoses at different rates,34 with African-American children being much more likely to receive an ADHD diagnosis before being diagnosed with autism.33 Differences in diagnostic labels across racial/ethnic groups may contribute to creating a group of African-American children diagnosed with ADHD who have intensive in-school service needs. Second, it is possible that African-American children who demonstrate externalizing behavior problems often associated with ADHD are more likely to be referred for in-school services by their teachers, as has been demonstrated in previous reports of disproportionalities in school-based referrals to special education and behavioral support services.35–36 Whereas more accurate and refined diagnostic assessments and referrals to service for African-American children may be needed,37 future research to determine what factors may explain higher in-school service use for African-American children with ADHD is needed. It also is possible that African-American children with ADHD use more intensive in-school behavioral health services to address their needs and more research is needed to understand if this is a factor.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, the geographic generalizability of the results is limited to the areas with similar racial/ethnic diversity and behavioral health services for children with psychiatric disorders; however, the findings may be generalizable to the large, urban school districts that serve a disproportionately large number of minority children and children with special needs.37 Second, the study was conducted using the Philadelphia behavioral health Medicaid claims data and does not take into account the potential role of other funding streams (the education system, private insurance, and out of pocket). Although these data are important for understanding one population of behavioral health users, additional research is needed to understand service use by different providers. Third, it was not possible to ascertain the linguistic backgrounds of the families from this dataset and whether accessing services was impacted by language skills; although, it is likely that language barriers may affect families’ procurement of services. Fourth, although all children had equal access to in-school individual behavioral health support through Medicaid, it was not possible to ascertain whether the schools also provided other behavioral health services such as counseling or medication management. Fifth, the difference in Medicaid expenditures across race/ethnic groups reflects the difference in volume of service use and does not reflect differences in quality of care. We did not have data to examine quality of services rendered in either in-school or out-of-school settings. Lastly, our analysis is based on one year of cross-sectional data of behavioral health claims. Additional research that includes the analysis of physical health and prescription claims combined with the behavioral health claims are likely to provide more meaningful racial/ethnic disparity information, as children might be prescribed medication for their behavioral symptoms through pediatricians and may not be identified as needing behavioral health services, thereby inflating the out of school to in school service ratio.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

This is one of the first studies to examine disparities in in-school and out-of-school behavioral health services and Medicaid expenditures across psychiatric diagnoses and race/ethnicity. The results suggest that significant disparities in in-school individual behavioral health service use exist by race/ethnicity and differ across psychiatric disorders. Additionally, significant disparities in Medicaid expenditures for out-of-school behavioral health service use by race/ethnicity exist and significantly differ across psychiatric disorders. There is a distinction between not using available services and not having access to needed services, which suggests the need for different types of interventions to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in the behavioral health system and schools. In this study, Hispanic children used the lowest amount of behavioral health Medicaid services across all diagnostic groups. The reasons for this disparity are unclear; however, the results indicate a large proportion of Hispanic children with psychiatric disorders that are being underserved, particularly in school settings. These data suggest that merely changing the setting in which services are delivered does not completely address existing disparities. In fact, school-based services may be necessary but not sufficient in ameliorating disparities among Hispanics. This disparity points to the need for culturally sensitive methods and targeted outreach services to inform Hispanic families of the critical need for intervention, as well as the need to concurrently implement interventions that are consistent with and sensitive to the cultural beliefs and practices of Hispanic families. Future research on how the higher use of in-school behavioral health service among African Americans with ADHD compared to other children with ADHD is associated with school outcomes as well as behavioral functioning will lead policymakers and practitioners to identify whether higher use is associated with better quality of in-school behavioral healthcare. Cultural awareness may affect assessment, diagnosis, and treatment3 resulting in disparities in access to and utilization of services among students with psychiatric disorders. Training behavioral health practitioners to provide culturally appropriate assessment and services will help alleviate disparities among all ethnic groups. Finally, tailoring in-school behavioral health service to be culturally appropriate by psychiatric disorder is important to reduce disparities in use.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

The University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol # 809866) and the Institutional Review Board of City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health (Protocol # 2009–27) approved this study. The Medicaid claims data were shared through the Memorandum of Understanding between the City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services and the University of Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services. The preparation of this article also was supported in part by the City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services, NIMH K01MH100199, the Autism Science Foundation (Grant # 13-ECA-01L) and FARFund Early Career Award (Locke).

Contributor Information

Jill Locke, University of Washington, Speech and Hearing Sciences, University of Washington Autism Center, Box 357920, Phone: 206-616-6703, jjlocke@uw.edu.

Christina D. Kang-Yi, University of Pennsylvania Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Philadelphia, PA 19104, ckangyi@upenn.edu.

Melanie Pellecchia, University of Pennsylvania Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Philadelphia, PA 19104, Phone: 215-746-1950, pmelanie@upenn.edu.

Steve Marcus, 3701 Locust Walk, Caster Building Room C16, Philadelphia, PA 19104, marcuss@sp2.upen.edu.

Trevor Hadley, University of Pennsylvania Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Philadelphia, PA 19104, thadley@upenn.edu.

David S. Mandell, University of Pennsylvania Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Center for Autism Research, Philadelphia, PA 19104, mandelld@upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer EMZ, Fairbank JA, Burns BJ, Keeler G, et al. Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and white youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):893–901. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen L, Huang LN, Arganza GF, Liao Q. The influence of race and ethnicity on psychiatric diagnoses and clinical characteristics of children and adolescents in children’s services. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007;13(1):18–25. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minsky S, Petti T, Gara M, Vega W, Lu W, Kiely G. Ethnicity and clinical psychiatric diagnosis in childhood. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33(5):558–567. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan PL, Hillemeier MM, Farkas G, Maczuga S. Racial/ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis by kindergarten entry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(8):905–913. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandell DS, Wiggins LD, Carpenter LA, Daniels J, DiGuiseppi C, Durkin MS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):493–498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alegría M, Lin JY, Green JG, Sampson NA, Gruber MH, Kessler RC. Role of referrals in mental health service disparities for racial and ethnic minority youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(7):703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.005. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alegría M, Vallas M, Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(4):759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slade EP. The relationship between school characteristics and the availability of mental health and related health services in middle and high schools in the United States. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2003;30(4):382–392. doi: 10.1007/BF02287426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Angold A, Costello EJ. Pathways into and through mental health services for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(1):60–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walter EE, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon AR, Frazier SL, Mehta T, Atkins MS, Weisbach J. Easier said than done: intervention sustainability in an urban after-school program. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(6):504–517. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0339-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kataoka S, Stein BD, Nadeem E, Wong M. Who gets care? Mental health service use following a school-based suicide prevention program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1341–1348. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31813761fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pullmann MD, VanHooser S, Hoffman C, Heflinger CA. Barriers to and supports of family participation in a rural system of care for children with serious emotional problems. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(3):211–220. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9208-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anglin TM. Mental health in schools: programs of the federal government. In: Weist MD, Evans SW, Lever NA, editors. Handbook of School Mental Health: Advancing Practice and Research. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flaherty LT, Osher D. History of school-based mental health services in the United States. In: Weist MD, Evans SW, Lever NA, editors. Handbook of School Mental Health: Advancing Practice and Research. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindly OJ, Sinche BK, Zuckerman KE. Variation in educational services receipt among US children with developmental conditions. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(5):534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delphin-Rittman ME, Flanagan EH, Andres-Hyman R, Ortiz J, Amer MM, Davidson L. Racial-ethnic differences in access, diagnosis, and outcomes in public-sector inpatient mental health treatment. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(2):158–166. doi: 10.1037/a0038858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, Aarons GA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):409–418. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang-Yi C, Locke J, Hadley T, Mandell DS. School-based behavioral health service use and expenditures for children with autism and children with other disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(1):101–106. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services. Utilizing Management Guide: Community Behavioral Health. Philadelphia, PA: Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services; 2006. [Accessed September 30, 2016]. Available at: http://www.dbhids.org/providers-seeking-information/community-behavioral-health/cbh-utilization-management-guide/. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shattuck PT, Grosse SD, Parish S, Bier D. Utilization of a Medicaid-funded intervention for children with autism. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):129–135. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magaña S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, Swaine JG. Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev. Disabil. 2012;50(4):287–299. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delphin-Rittmon M, Bellamy CD, Ridgway P, Guy K, Ortiz J, Flanagan E, et al. ‘I never really discuss that with my clinician’: US consumer perspectives on the place of culture in behavioural healthcare. Divers Equal Health Care. 2013;10(3):143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gay G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2nd. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch E, Hanson MJ. Developing Cross-cultural Competence: A Guide for Working with Children and Their Families. 3rd. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothstein-Fisch C, Trumbull E. Developing Cross-cultural Competence: A Guide for Working with Children and Families. 3rd. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim G, Loi CXA, Chiriboga DA, Jang Y, Parmelee P, Allen RS. Limited English proficiency as a barrier to mental health service use: a study of Latino and Asian immigrants with psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(1):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Q, Brabeck K. Service utilization for Latino children in mixed-status families. Soc Work Res. 2012;36(3):209–221. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandell DS, Ittenbach RF, Levy SE, Pinto-Martin JA. Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(9):1795–1802. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilgus MD, Pumareiga AJ, Cuffe SP. Influence of race on diagnosis of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(1):67–72. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199501000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NASP Position Statement. Racial and Ethnic Disproportionality in Education. National Association of School Psychologists. 2013. [Accessed September 30, 2016]. Available at: www.nasponline.org. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skiba RJ, Horner RS, Chung CG, Rausch MK, May SL, Tobin T. Race is not neutral: a national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. School Psych Rev. 2011;40(1):85–107. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sable J, Plotts C, Mitchell L. Characteristics of the 100 Largest Public Elementary and Secondary School districts in the United States: 2008–09 (NCES 2011-301) Washington, DC: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]