Identification of a potential mechanism linking land-use change and the emergence of an infectious disease

Keywords: Land-use, deforestation, foodwebs, anthropogenic change, emerging infectious disease, stable isotopes, French Guiana, Buruli ulcer

Abstract

Generalist microorganisms are the agents of many emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), but their natural life cycles are difficult to predict due to the multiplicity of potential hosts and environmental reservoirs. Among 250 known human EIDs, many have been traced to tropical rain forests and specifically freshwater aquatic systems, which act as an interface between microbe-rich sediments or substrates and terrestrial habitats. Along with the rapid urbanization of developing countries, population encroachment, deforestation, and land-use modifications are expected to increase the risk of EID outbreaks. We show that the freshwater food-web collapse driven by land-use change has a nonlinear effect on the abundance of preferential hosts of a generalist bacterial pathogen, Mycobacterium ulcerans. This leads to an increase of the pathogen within systems at certain levels of environmental disturbance. The complex link between aquatic, terrestrial, and EID processes highlights the potential importance of species community composition and structure and species life history traits in disease risk estimation and mapping. Mechanisms such as the one shown here are also central in predicting how human-induced environmental change, for example, deforestation and changes in land use, may drive emergence.

INTRODUCTION

Despite a large percentage of the approximately 250 known human emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) that have been traced to tropical forests (1), precise mechanistic details of the association often remain elusive. A consequence of the rapid increase in human populations, settlements, and encroachments globally is the concomitant rapid decline in biological diversity, with significant shifts in species community composition and severe disruption to established food webs, which are directly tractable to land-use change and deforestation (2–4). The results include advanced effects on ecosystem functioning and the potential for marked changes in associated microbial dynamics (5–8), including impact on resident human populations.

Estimates suggest that 10,000 to 20,000 freshwater species are under severe threat of extinction (9–12). Riparian systems act as an interface between the environment and hosts and/or vectors of many human disease agents. Currently, the understanding of the consequences of changes in freshwater communities on the incidence and epidemiology of human EIDs is limited, and empirical evidence is still scarce (6, 13–15). The effects of deforestation and land use on potential aquatic infectious agent hosts have been described predominantly for established vector-transmitted diseases, notably malaria (16). These are clearly of interest because of the large number of human cases and known vectors or hosts that can be more readily surveyed and the data used as proxy for potential infection rates.

To potentially understand the more generalist EIDs, which often do not rely on a single specific host or vector species (17), extensive analysis of shifts in host/nonhost communities caused by natural habitat modifications and/or land-use change is required. For example, hosts of differing suitability will be dissimilarly adapted to modified environments; therefore, it is critical to quantify their relationship with an EID. In addition, land use or habitat change often results in a shift in trophic interactions, which can be a direct (for example, predation) or indirect (for example, extinction cascade) modification of the food-web structure. A severe change in a trophic network may have a significant impact on an EID, with promotion or decline of certain host species in the community network.

Here, we tested for the first time the links between the drivers of trophic community networks in tropical freshwater ecosystems and the emergence of a generalist microbial agent, Mycobacterium ulcerans, which causes the human skin disease, Buruli ulcer. A detailed structural presentation of the host and nonhost interaction under varying levels of anthropogenic stress related to M. ulcerans will be provided. The empirical relatedness of the structural changes in the host and nonhost community networks to the biomass of M. ulcerans will also be characterized.

RESULTS

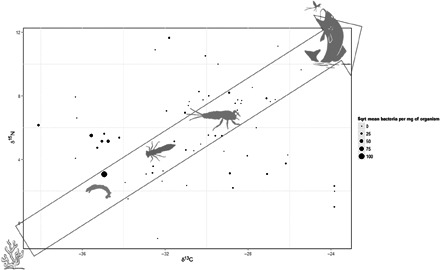

More than 3600 invertebrates and fish were collected and cataloged from 17 freshwater sites across French Guiana, a French territory endemic for Buruli ulcer. A total of 78 different freshwater taxa were identified, of which 383 specimens representing 44 taxa tested positive for both IS2404 and KR (ketoreductase B) molecular markers (Table 1). M. ulcerans concentrations ranged from 6 to 10,385 bacillus cells per milligram of organism (mean, 1405; SD, ±2109). The highest concentrations of M. ulcerans were in species lower in the food chain, represented by low δ15N and δ13C stable isotope readings, suggesting a diet high in aquatic algae, detritus, diatoms, and similar food sources (Fig. 1). These taxa, in the upper quartile of the M. ulcerans load, were predominantly invertebrates in both adult and larval form, including Corixidae, Caenidae, Coenagrionidae, Baetidae, Veliidae, Leptophlebiidae, and Simuliidae, and two freshwater fish species, Copella carsevenennsis and Rivulus lungi.

Table 1. Primers and probes for real-time PCR detection.

Nucleotide position based on the first copy of the amplicon in pMUM001 (accession numbers: IS2404, AF003002; KR, BX649209). TF, forward primer; TR, reverse primer; TP, probe.

| Primer or probe | Sequence (5′-3′) | Nucleotide positions | Amplicon size (base pairs) |

| IS2404 TF | AAAGCACCACGCAGCATCT | 27746–27762 | 59 |

| IS2404 TR | AGCGACCCCAGTGGATTG | 27787–27804 | |

| IS2404 TP | 6 FAM-CGTCCAACGCGATC-MGBNFQ | 27768–27781 | |

| KR TF | TCACGGCCTGCGATATCA | 3178–3195 | 65 |

| KR TR | TTGTGTGGGCACTGAATTGAC | 3222–3242 | |

| KR TP | 6 FAM-ACCCCGAAGCACTG-MGBNFQ | 3199–3212 |

Fig. 1. The average δ15N and a low δ13C in biplot space for all recorded host and nonhost organisms from the 17 sites.

δ15N and δ13C were derived for each host taxon using data from the three sites analyzed for stable isotopic readings and extrapolated to the additional 14 sites. For each point, the square root–transformed mean number of M. ulcerans of the host is represented by the size of the circle.

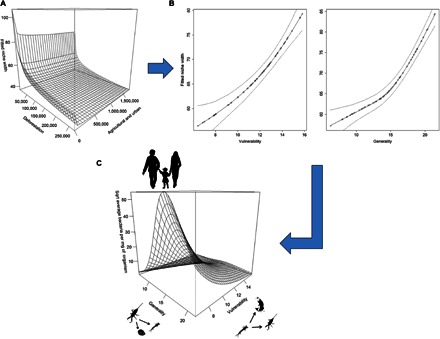

Deforestation and either agricultural or urban intrusion led to a decline in local trophic niche width (metric of total available niche space within a site) (adjusted R 2 = 0.557; deviance explained = 62.2%; deforestation: P = 0.0008, F = 17.719; agriculture/urban land use: P = 0.0265, F = 6.228) (Fig. 2A), resulting in decreased regional mean vulnerability of taxa (number of potential predator species each prey taxa has), coupled with a decrease in generality (number of potential prey species each predator taxa can consume) (vulnerability: adjusted R2 = 0.335, deviance explained = 35.8%, F = 20.67, P < 0.0001; generality: adjusted R 2 = 0.528, deviance explained = 54.3%, F = 29.31, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2B). This had an important, nonlinear effect on the potential local M. ulcerans load. Host taxa, which on average carried a high level of M. ulcerans, were most abundant at sites where there was a very low level of vulnerability and a midlevel of generality (adjusted R2 = 0.482; deviance explained = 36%; generality: P = 0.0003, F = 7.303; vulnerability: P < 0.0001, F = 18.871) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Figure showing the relationships between land-use, deforestation and M. ulcerans.

(A) Plot showing the relationship between local site niche widths and the level of agricultural and urban landscape and deforestation in a 1-km buffer zone. The change in niche width caused by deforestation appears to be a steady decline, whereas the presence of agricultural land causes a sharp drop from where there is no agriculture, before exhibiting a similar steady decline in niche width as with deforestation, albeit less extreme. (B) Plot showing decline in vulnerability and generality as niche width declines with 95% confidence intervals. (C) Plot showing metrics of the food-web networks that allow taxa, which on average carry a higher M. ulcerans load to propagate. For all taxa, along the bottom axes are the mean regional food-web metrics for vulnerability and generality (that is, a measure of the food-web metrics of sites at which they are most abundant; see Materials and Methods for details), whereas the vertical axis shows the mean regional bacterial load of M. ulcerans.

DISCUSSION

The characterization of a relationship between the abundance of a bacterial pathogen, host species community structure, and land cover provides key information on the ecological pathways of an infectious agents’ emergence. Understanding such pathways is central to modeling the impact of global changes on EIDs in tropical areas and predicting infectious risk in developing countries.

The nonlinear increase in the potential abundance of M. ulcerans under the anthropogenic stresses of land-use change and deforestation can, in this instance, be attributed to an increase of preferred hosts [identified by the regional mean M. ulcerans load attained using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)], represented by predominantly low–trophic level organisms (Fig. 2). At sites of low vulnerability, some basal host species flourish because of a decrease or disappearance of predation. However, if a site has a high level of generality, the number of basal host species is highly variable with a functionally more restrictive or fluctuating niche space. As the diversity of basal organisms begins to decrease (indicated by a loss in generality), the abundance of M. ulcerans hosts and thus the M. ulcerans load then start to increase, until the number of basal organisms becomes too low, leading again to a decrease in M. ulcerans.

As urbanization, agriculture, and deforestation intensify, notably in tropical regions of the world (which also hosts the largest number of developing countries on the planet), similar trends for other EIDs, as observed here for M. ulcerans, may become apparent. One hypothesis is that basal opportunistic and highly fecund species (that is, r strategists) within a trophic food web could form a hotspot for many bacterial or viral pathogens. In both aquatic and terrestrial environments, many of the basal taxa live at the interfaces of soil and water or soil and vegetation, and their high numbers and potential reduced investment in immunity (18–21) allow for many opportunities for emerging microbes to take hold or opportunistic microbes to make the leap from commensalism or symbiosis to pathogenesis (22). Although this hypothesis is plausible for some species, evidence within the literature is still debated and more studies in this field are required to prove a definitive link (13, 14).

Because human populations have greater contact with land-use change generated by global urbanization, it is not unreasonable to predict that emergence and reemergence of infectious diseases will become more common. We therefore recommend that more empirical evidence must be sought for mechanisms related to disease emergence in areas of anthropogenic disturbance, notably in tropical regions of the world where biodiversity (at both micro- and macroscales) can be high. Although this study identifies a potential mechanism for a specific (albeit important) emerging disease, the generalizability of these results needs further testing. The relationships EIDs have with other organisms and the environment are complex and are dictated by a multitude of factors, which must be individually explored. In doing so, we will increase our chances of predicting and understanding the risk posed by these pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study location

French Guiana is an extraperipheral territory of France, bordering Brazil to the east and south and Suriname to the west. Although large in area at 83,534 km2, the population density is relatively low, with almost all inhabitants located in a thin strip along the coastline. The rest of the country is predominantly pristine primary tropical rain forest including 33,900 km2 of the Guiana Amazonian National Park and a wealth of important ecosystems ranging from marshland to coastal mangroves. Since 1969, the number of Buruli ulcer cases has remained steady but unusually high in comparison to that of other countries in the surrounding region (25, 29). The disease is endemic in close to 30 tropical and subtropical countries, where it can affect health and lead to serious socioeconomic consequences (30).

Data collection

Seventeen locations with freshwater sites in French Guiana suitable for study were identified as endemic or having the potential to harbor M. ulcerans according to previously published data (29).These sites are empirically similar but have gradients of land use from urban through agricultural to pristine rain forest. Each site was surveyed in the rainy season twice, during February and June 2013. Samples of aquatic invertebrates, fish, and other small aquatic vertebrates were collected and analyzed as follows.

Invertebrate samples were collected at four locations, spatially distributed within each site to include a range of microhabitats. Nets were used to vigorously collect samples from the bottom sediment and the surface of the water column within a meter square area. All collected samples were placed on a white tray for preliminary sorting in the field and fixed in 70% ethanol for subsequent identification and storage in the laboratory.

Fish were collected using three standard baited fish traps and spatially distributed as the dip net locations (see above). Traps were left in place for 1.5 hours before retrieval. Fish were collected and euthanized using a 400-mg to 1-liter solution of clove oil. The solution was added gradually, and fish remained submerged for 10 min until death, following the guidelines set out by the American Veterinary Medical Association as advocated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (31). Fish were then preserved in 70% alcohol for sorting and identification back at the laboratory. Fish were collected under a U.K. personal license for regulated animal procedures held by R. E. Gozlan and adhered to the French and European laws. The project was approved by the Bournemouth University Ethics Committee and was performed under the Home Office project license number PPL80/1979.

Identification and data collection

The length of each invertebrate was measured, and identification was conducted predominantly to family level where possible, using a number of literature sources (32–36). Specimens of the same family were pooled by site and collection date and preserved in 70% alcohol for qPCR analysis. Invertebrates containing more than 10 individuals were pooled in series of 10. Dry weights in milligrams were calculated using length to mass regression equations (37–39). Fish were identified to species level (40, 41), and for each individual, a standardized length measurement was taken. Fish weights were also calculated using length to weight regression equations (42); however, because there is no direct conversion available in the literature for fish to establish dry weights for all species, an average wet to dry weight conversion of 20% was used. For qPCR, the fish were pooled in groups of three individuals per species per sample (dip net or trap), an important step for the analysis of trapped fish because they are likely to congregate in very large numbers within a trap. Therefore, this threshold was applied for the abundance to be relative to a small sample area for invertebrates.

Quantitative PCR

Pooled organisms were homogenized in 50 mM NaOH solution using the Qiagen TissueLyser II. Tissues were heated at 95ºC for 20 min. DNA from the homogenized tissue was purified using the QIAquick 96 PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The 10% negative controls were included for extraction and purification.

Oligonucleotide primer and TaqMan probe sequences were selected from GenBank IS2404 sequences (43), a more generic marker for mycolactone-producing mycobacteria and KR domain of the mycolactone polyketide synthase (mls) gene from the plasmid pMUM001 (Table 1) (44), which is highly specific to M. ulcerans. qPCR mixtures contained 5 μl of template DNA, 0.3 μM concentration of each primer, 0.25 μM concentration of the probe, and Brilliant II QPCR Master Mix with Low ROX (Agilent Technologies) in a total volume of 25 μl. Amplification and detection were performed with Thermocycler (Chromo4, Bio-Rad) using the following program: 1 cycle at 50ºC for 2 min, 1 cycle at 95ºC for 15 min, 40 cycles at 95ºC for 15 s and at 60ºC for 1 min. DNA extracts were tested in duplicate, and the 10% negative controls were included in each assay. Quantitative readout assays were established on the basis of an external standard curve with M. ulcerans (strain 1G897) DNA serially diluted over 5 logs (from 106 to 102 U/ml). Samples were considered positive only if both the gene sequence encoding the KR domain of the mls and IS2404 sequence were detected, with threshold cycle (Ct) values strictly <35 cycles [see the studies of Garchitorena et al. (26) and Morris et al. (29)]. The number of bacilli in the sample was estimated from the PCR data of KR because it is more specific to M. ulcerans.

Stable isotope analysis

Stable isotope analysis was conducted on all invertebrates and vertebrates from three sites for both collection dates for the stable isotope signatures of δ13C and δ15N. This covered the majority of the taxa present at all 17 sites and was applied to the same taxa from other sites (table S1). For invertebrate analysis, a limb of the organism was used, or if it was too small and many were present, whole organisms were used. For fish, caudal fin clippings were used. A minimum amount of material was taken to preserve organisms for qPCR analysis. In most cases, three samples of each taxonomic group were analyzed for each site. However, because of the limited number of available organisms one or two samples were used in some cases. For any taxa that were not analyzed due to abundance limitations, stable isotope data from a closely related and functionally highly similar taxon were recorded for use in the statistical analysis. The material was dried at 40ºC for 8 hours to remove all traces of moisture. After drying, the material was homogenized, and the stable isotope signatures of δ13C and δ15N were identified using a Finnigan MAT Delta Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer.

Trophic niche width and food-web metric calculations of sites and aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates

Trophic niche width (a metric of total available niche space within a site) (45) was calculated from the stable isotope data as the total convex hull area of the mean δ13C and δ15N isotopic readings in biplot space for the entire surveyed population of all organisms within a site (fig. S1). As a measure of available niche space, niche width can be seen as a useful metric for quantifying how capable a community is at exploiting its current environment, something that will be directly affected by land use and/or deforestation.

The allometric diet breadth model (ADBM) was used to predict links between nodes in each food web, and these were subsequently tested for accuracy from previous knowledge. Any biologically inaccurate or missing links were updated accordingly. The ADBM is based on the mass of an organism and, in some cases, assumes a larger organism to prey on a smaller one. However, without providing biological and behavioral information for all taxa, in some instances, this is not precise. Therefore, all food webs must be checked for missing or inaccurate links.

Once a network was estimated, a number of average local metrics were calculated for each site (table S2). This included the connectance (that is, a measure of the number of node connections in a food web) or link density, the generality (a measure of the average number of different organisms a taxon can feed on), and the vulnerability (a measure of the average number of species by which an organism is preyed upon).

Landscape data

Landscape data were extracted from two maps. The first was the 25-m-resolution French Ministère de l’Écologie, du Développement Durable et de l’Énergie CORINE Land Cover 2006 based on the CORINE 2006 European land cover map using satellite-derived data from 2005 and 2008. The second comprised the Hansen deforestation maps, which consists of a high-resolution map of global forest change to 30-m resolution, with individual data for each year from 2001 to 2012 (46). Each site location was plotted on the land cover maps, and a 1-km buffer zone was drawn around each. From within the buffer zone, land cover data in square meters were extracted for the CORINE map and deforestation data for the years 2010 to 2012 for the Hansen’s map (table S3). Data extraction was conducted in Quantum GIS using the LecoS landscape data analysis plug-in (47). For two sites, which were considered “pristine” and located outside the small villages further into the forest, the CORINE Land Cover map did not cover the area. Therefore, data from the GlobCover 2009 Global Land Cover Map were used (48). This map, although lower resolution for French Guiana, was used only for two sites, which were buffered by almost entirely forest. The retrieved data were considered sufficient for comparisons to be made.

Analysis

For each taxon identified during the surveys, the regional mean M. ulcerans load was calculated from the qPCR data, encompassing all sites, survey dips, and dates, that is, representing a taxonomic group average bacterial load if found in the wild, based on information gathered for each site. In addition, each taxon’s regional mean niche width, vulnerability, connectance, and generality were also derived and weighted by the abundance at each site (that is, if a species occurred predominantly at sites with low generality, its average generality metric would be lower).

To identify whether those host taxa with a higher mean M. ulcerans load were most common at sites with a certain type of food-web structure (for example, high levels of connectance, generality, or vulnerability), general additive models (GAMs) were run, with a tensor product smoothing performed between the regional M. ulcerans load and their mean regional food-web metrics (connectance, vulnerability, and generality). Nonsignificant metrics were removed until a final best-fit model was found. Because many taxa had no M. ulcerans across all sites, a Tweedie’s probability distribution was used, as this distribution is well suited to zero-inflated models and provided the best-fit to the data (49). To identify how generality, connectance, and vulnerability responded to a reduction in niche width of the population, GAMs of each metric (that is, vulnerability, generality, and connectance as a function of niche width) were run separately.

The relationships between land cover data and niche width were identified at the local site level using GAMs of the level of deforestation in square meters within each buffer zone in addition to urban and agricultural cover (square meters). For deforestation, data from the preceding 3 years of the survey date were used; this was done to allow for enough data to be available for each site but not to be too far from the survey as to be unlikely to have an effect. This period was also 1 year preceding 2008, when the last SPOT-5 satellite data for the agricultural and urban land cover were collected, so it is possible to be confident that this land type was present when deforestation occurred.

In all models, the data were appropriately transformed to adhere to model assumptions, and the residuals of each model were tested for spatial autocorrelation using both Moran’s I test (95% confidence interval) and CorreLogs smoothed with a spline function (95% pointwise bootstrap confidence intervals) (50). Further model checking was performed using q-q plots and residual plots against fitted values, with any significant outliers removed. This constituted the following: Polymitarcyidae, a family of mayflies with only one individual found from all sites, with a very high level of M. ulcerans (10,385 per milligram), a possible PCR anomaly; a single individual of the order Trichoptera found with very low regional convex hull measurements; Cleithracara maronii, a species of fish, also a single individual found with a very low regional convex hull measurement; and a single sample of Moenkhausia hemigrammoides from a single site found to be a significant outlier when model checking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank V. O. Ezenwa and R. Colwell for their comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We would also like to thank O. Petchey for use of his R script for calculating the ADBM. Funding: This work has benefited from a 3-year Bournemouth University PhD fellowship grant to A.L.M. A.L.M., J.-F.G., M.L.C., K.C., D.S., and R.E.G. have benefited from an “Investissement d’Avenir” grant managed by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (CEBA; reference ANR-10-LABX-2501). J.-F.G. is sponsored by the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and R.E.G. is sponsored by IRD. L.M. and J.-F.G. are funded by an Equipe Inserm Avenir “ATOMycA” delivered to L.M. D.S. was funded by BECAS CHILE (CONICYT PAI/INDUSTRIA 79090016). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the ANR or ATIPE Avenir INSERM. Author contributions: A.L.M., R.E.G., and J.-F.G. designed the experiment. A.L.M., K.C., and M.L.C. carried out data collection. A.L.M., L.M., and D.S. carried out genetic analysis. A.L.M. performed the statistical analysis, A.L.M., J.-F.G. and R.E.G. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/12/e1600387/DC1

fig. S1. The average δ15N and a low δ13C in biplot space for each taxonomic group at each of the 17 sites.

table S1. The mean regional food-web, stable isotope, and qPCR metrics for all taxa.

table S2. Site location, local food-web metrics, and niche width for the 17 sites sampled in this study.

table S3. Anthropogenic change within 1 km of the environmental change.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Despommier D., Ellis B. R., Wilcox B. A., The role of ecotones in emerging infectious diseases. Ecohealth 3, 281–289 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinney M. L., Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosyst. 11, 161–176 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinney M. L., Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol. Conserv. 127, 247–260 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahel F. J., Homogenization of freshwater faunas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33, 291–315 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapin F. S. III, Zavaleta E. S., Eviner V. T., Naylor R. L., Vitousek P. M., Reynolds H. L., Hooper D. U., Lavorel S., Sala O. E., Hobbie S. E., Mack M. C., Díaz S., Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 405, 234–242 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keesing F., Belden L. K., Daszak P., Dobson A., Harvell C. D., Holt R. D., Hudson P., Jolles A., Jones K. E., Mitchell C. E., Myers S. S., Bogich T., Ostfeld R. S., Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 468, 647–652 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostfeld R. S., Keesing F., Biodiversity series: The function of biodiversity in the ecology of vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Can. J. Zool. 78, 2061–2078 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostfeld R. S., Biodiversity loss and the rise of zoonotic pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15 (suppl. 1), 40–43 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vörösmarty C. J., McIntyre P. B., Gessner M. O., Dudgeon D., Prusevich A., Green P., Glidden S., Bunn S. E., Sullivan C. A., Liermann C. R., Davies P. M., Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 467, 555–561 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvell C. D., Mitchell C. E., Ward J. R., Altizer S., Dobson A. P., Ostfeld R. S., Samuel M. D., Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science 296, 2158–2162 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleick P. H., Global freshwater resources: Soft-path solutions for the 21st century. Science 302, 1524–1528 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meybeck M., Global analysis of river systems: From Earth system controls to Anthropocene syndromes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 1935–1955 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randolph S. E., Dobson A. D. M., Pangloss revisited: A critique of the dilution effect and the biodiversity-buffers-disease paradigm. Parasitology 139, 847–863 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roche B., Guégan J.-F., Ecosystem dynamics, biological diversity and emerging infectious diseases. C. R. Biol. 334, 385–392 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones K. E., Patel N. G., Levy M. A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J. L., Daszak P., Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vittor A. Y., Pan W., Gilman R. H., Tielsch J., Glass G., Shields T., Sánchez-Lozano W., Pinedo V. V., Salas-Cobos E., Flores S., Patz J. A., Linking deforestation to malaria in the Amazon: Characterization of the breeding habitat of the principal malaria vector, Anopheles darlingi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 81, 5–12 (2009). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachs J. L., Skophammer R. G., Regus J. U., Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (suppl. 2), 10800–10807 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee K. A., Wikelski M., Robinson W. D., Robinson T. R., Klasing K. C., Constitutive immune defences correlate with life-history variables in tropical birds. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 356–363 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin L. B. II, Hasselquist D., Wikelski M., Investment in immune defense is linked to pace of life in house sparrows. Oecologia 147, 565–575 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin L. B. II, Weil Z. M., Nelson R. J., Immune defense and reproductive pace of life in peromyscus mice. Ecology 88, 2516–2528 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunn C. L., Gittleman J. L., Antonovics J., A comparative study of white blood cell counts and disease risk in carnivores. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 270, 347–356 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachs J. L., Essenberg C. J., Turcotte M. M., New paradigms for the evolution of beneficial infections. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 202–209 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau C. L., Smythe L. D., Craig S. B., Weinstein P., Climate change, flooding, urbanisation and leptospirosis: Fuelling the fire? Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 104, 631–638 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrianaivoarimanana V., Kreppel K., Elissa N., Duplantier J.-M., Carniel E., Rajerison M., Jambou R., Understanding the persistence of plague foci in Madagascar. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2382 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris A., Gozlan R. E., Hassani H., Andreou D., Couppié P., Guégan J.-F., Complex temporal climate signals drive the emergence of human water-borne disease. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 3, e56 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garchitorena A., Roche B., Kamgang R., Ossomba J., Babonneau J., Landier J., Fontanet A., Flahault A., Eyangoh S., Guégan J.-F., Marsollier L., Mycobacterium ulcerans ecological dynamics and its association with freshwater ecosystems and aquatic communities: Results from a 12-month environmental survey in cameroon. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2879 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Ravensway J., Benbow M. E., Tsonis A. A., Pierce S. J., Campbell L. P., Fyfe J. A. M., Hayman J. A., Johnson P. D. R., Wallace J. R., Qi J., Climate and landscape factors associated with Buruli ulcer incidence in Victoria, Australia. PLOS ONE 7, e51074 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche B., Benbow M. E., Merritt R., Kimbirauskas R., McIntosh M., Small P. L. C., Williamson H., Guégan J.-F., Identifying the Achilles heel of multi-host pathogens: The concept of keystone “host” species illustrated by Mycobacterium ulcerans transmission. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 045009 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris A., Gozlan R., Marion E., Marsollier L., Andreou D., Sanhueza D., Ruffine R., Couppié P., Guégan J.-F., First detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans DNA in environmental samples from South America. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2660 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garchitorena A., Ngonghala C. N., Guégan J.-F., Texier G., Bellanger M., Bonds M., Roche B., Economic inequality caused by feedbacks between poverty and the dynamics of a rare tropical disease: The case of Buruli ulcer in sub-Saharan Africa. Proc. Biol. Sci. 282, 20151426 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.S. Leary, W. Underwood, R. Anthony, S. Cartner, D. Corey, T. Grandin, C. Greenacre, S. Gwaltney-Brant, M. A. McCrackin, R. Meyer, D. Miller, J. Shearer, R. Yanong, AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.E. Domínguez, C. Molineri, M. L. Pescador, M. D. Hubbard, C. Nieto, Ephemeroptera de América del Sur (Pensoft Publishers, 2006), vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.C. W. Heckman, Encyclopedia of South American Aquatic Insects: Hemiptera-Heteroptera: Illustrated Keys to Known Families, Genera, and Species in South America (Springer, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 34.C. W. Heckman, Encyclopedia of South American Aquatic Insects: Odonata-Anisoptera: Illustrated Keys to Known Families, Genera, and Species in South America (Springer, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 35.C. W. Heckman, Encyclopedia of South American Aquatic Insects: Odonata-Zygoptera: Illustrated Keys to Known Families, Genera, and Species in South America (Springer, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36.R. W. Merritt, K. W. Cummins, An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America (Kendall Hunt Publishing Company, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benke A. C., Huryn A. D., Smock L. A., Wallace J. B., Length-mass relationships for freshwater macroinvertebrates in North America with particular reference to the southeastern United States. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 18, 308–343 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smock L. A., Relationships between body size and biomass of aquatic insects. Freshwater Biol. 10, 375–383 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miserendino M. L., Length–mass relationships for macroinvertebrates in freshwater environments of Patagonia (Argentina). Ecol. Aust. 11, 3–8 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 40.P.-Y. Le Bail, P. Keith, P. Planquette, Atlas des Poissons d’eau Douce de Guyane (Les Publications Scientifiques du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 41.P. Keith, P. Y. Le Bail, P. Planquette, Atlas des Poissons d’eau Douce de Guyane. Tome 2 Fascicule I, Batrachoidiformes, Mugiliformes, Beloniformes, Cyprinodontiformes, Synbranchiformes, Perciformes, Pleuronectiformes, Tetraodontiformes (Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Froese R., Thorson J. T., Reyes R. B., A Bayesian approach for estimating length-weight relationships in fishes. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 30, 78–85 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stinear T., Ross B. C., Davies J. K., Marino L., Robins-Browne R. M., Oppedisano F., Sievers A., Johnson P. D. R., Identification and characterization of IS2404 and IS2606: Two distinct repeated sequences for detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 1018–1023 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fyfe J. A. M., Lavender C. J., Johnson P. D. R., Globan M., Sievers A., Azuolas J., Stinear T. P., Development and application of two multiplex real-time PCR assays for the detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans in clinical and environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4733–4740 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Layman C. A., Arrington D. A., Montaña C. G., Post D. M., Can stable isotope ratios provide for community-wide measures of trophic structure? Ecology 88, 42–48 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen M. C., Potapov P. V., Moore R., Hancher M., Turubanova S. A., Tyukavina A., Thau D., Stehman S. V., Goetz S. J., Loveland T. R., Kommareddy A., Egorov A., Chini L., Justice C. O., Townshend J. R. G., High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.M. Jung, LecoS—A QGIS Plugin for Automated Landscape Ecology Analysis (PeerJ PrePrints, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 48.O. Arino, V. Kalogirou, P. Defourny, F. Achard, GlobCover 2009 (ESA Living Planet Symposium, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 49.M. C. K. Tweedie, An index which distinguishes between some important exponential families, in Statistics: Applications and New Directions. Proceedings of the Indian Statistical Institute Golden Jubilee International Conference, J. K. Ghosh, J. Roy, Eds (Indian Statistical Institute, 1984), pp. 579–604. [Google Scholar]

- 50.BjØrnstad O. N., Falck W., Nonparametric spatial covariance functions: Estimation and testing. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 8, 53–70 (2001). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/12/e1600387/DC1

fig. S1. The average δ15N and a low δ13C in biplot space for each taxonomic group at each of the 17 sites.

table S1. The mean regional food-web, stable isotope, and qPCR metrics for all taxa.

table S2. Site location, local food-web metrics, and niche width for the 17 sites sampled in this study.

table S3. Anthropogenic change within 1 km of the environmental change.