Abstract

Objective

Although cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) represents the first-line evidence-based psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa (BN), most individuals seeking treatment do not have access to this specialized intervention. We compared an Internet-based manualized version of CBT group therapy for BN conducted via a therapeutic chat group (CBT4BN) to the same treatment conducted via a traditional face-to-face group therapy (CBTF2F).

Method

In a two-site, randomized, controlled non-inferiority trial, we tested the hypothesis that CBT4BN would not be inferior to CBTF2F. One hundred forty-nine adult patients with BN (2.6% males) received up to 16 sessions of group CBT over 20 weeks in either CBT4BN or CBTF2F and outcomes were compared at the end of treatment and 12-month follow-up.

Results

At the end of treatment, CBT4BN was inferior to CBTF2F in producing abstinence from binge eating and purging and in leading to reductions in the frequency of binge eating and purging. However, by 12-month follow-up, CBT4BN was mostly not inferior to CBTF2F. Participants in the CBT4BN condition, but not CBTF2F, continued to reduce their binge-eating and purging frequency from end of treatment to 12-month follow-up.

Conclusions

CBT delivered online in a group chat format appears to be an efficacious treatment for BN although the trajectory of recovery may be slower than face-to-face group therapy. Online chat groups may increase accessibility of treatment and represent a cost-effective approach to service delivery. However, barriers in service delivery such as state-specific license and ethical guidelines for online therapists need to be addressed.

Background

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the first-line evidence-based psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa (BN) in adults [1–3]. Approximately 40–60% of patients who complete this treatment demonstrate significant improvement [3]; group and individual CBT are similarly effective[4] although some have found that group CBT is less likely to produce abstinence from binge eating and purging [4].

Patients with BN struggle with a fragmented system of care and social barriers to treatment. Well-trained CBT therapists and eating disorder specialists are difficult to locate [5]. Treatment may require considerable travel to university hospitals or specialty clinics and a substantial time and financial commitment [6]. Although group CBT is more economical, group delivery can deter patients who experience social anxiety or shame from seeking treatment [7, 8].

In response to these barriers, mental health services using online computer-mediated communication technologies (e.g., videoconferencing, mobile self-monitoring, text messaging, chat groups, digital coaching, and online self-help training) have emerged to fill gaps in service delivery and have demonstrated promise in treating bulimic symptoms [9–13]. An advantage of the chat group format is that it provides anonymity to all meeting participants, which can facilitate discussion of sensitive issues and promote openness and self-disclosure [9, 14]. Also, patients in chat-group psychiatric treatment have reported high levels of community, support, and acceptance that approach acceptability ratings of face-to-face treatment [15]. No studies, however, have evaluated whether group therapy delivered via a “chat” room is as effective as face-to-face group therapy for BN [16].

The objective of the current investigation was to compare the efficacy of a therapist-moderated chat group for BN (CBT4BN) to traditional face-to-face group CBT for BN (CBTF2F). We hypothesized that an online group chat would be an acceptable platform to disseminate evidence-based treatment for BN and that CBT4BN would not be inferior to CBTF2F. We expected that patients in both conditions would be equally likely to experience abstinence from binge eating and purging behaviors at the end of treatment and at the 12-month follow-up.

Methods

Design and Procedure

The randomized controlled trial was designed as a two-site non-inferiority trial. The institutional review boards at both institutions approved the trial and all patients provided informed consent. Details regarding the design, methods, and treatment of the study have been published previously, registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00877786), and can be found in Online Supplement: Methods [17, 18]. Patients were assessed at baseline, end of treatment, and 12-month follow-up. During the follow-up period, patients had no further therapeutic contact with study personnel.

Participants

Patients were recruited via clinical referrals and completed a telephone screen to assess inclusion and exclusion criteria before an in-person baseline assessment. The CONSORT Flow Diagram (Online Figure 1) summarizes participant enrollment and study flow. Details about inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trial can be found in Online Supplement: Methods. Analyses were conducted on the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample and included all randomized participants, except patients who were terminated from the study (due to changes in status that led them to meet exclusion criteria during the course of the trial) or withdrew consent.

Treatment

Participants in both groups participated in 16, 90-minute group CBT sessions delivered over 20 weeks (12 weekly followed by 4 bi-weekly sessions). Groups were therapist-led and included 3–5 patients. Modules included psychoeducation, self-monitoring, normalization of meals, cue identification, challenging automatic thoughts, thought restructuring, chaining, and relapse prevention—with sections on body image, assertiveness, and cultural messages [19]. Two sessions focused on the dietary exchange system and were moderated by a registered dietitian. Treatment content and duration were equivalent in CBT4BN and CBTF2F, but the delivery method differed. Patients in CBT4BN groups convened with the therapist via an online chat group; patients in CBTF2F met the therapist and group members face-to-face for each session. Treatment completion was defined as attendance at ≥75% of treatment sessions. Additional details about the treatment and therapist supervision and adherence can be found in Online Supplement: Methods.

Assessment

Additional details about the assessments can be found in Online Supplement 1: Methods.

Eating Disorder Symptoms

The Eating Disorder Examination interview (EDE) was administered at baseline, end of treatment, and follow-up by assessors blind to the patient’s treatment condition [20]. The primary outcome variable was abstinence from binge eating and purging (0 episodes over the previous 28 days). Secondary outcome variables included BN diagnosis and the frequency of binge and purge episodes and the tertiary outcome included the global EDE score.

Comorbid Psychopathology

Tertiary outcomes measured by the SCID-I/P [21] included the presence of a major depressive disorder or anxiety disorder (i.e., social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobia). Depression and anxiety severity were measured by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [22, 23].

Quality of Life

Quality of life was measured by the Eating Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire (EDQOL) and the Short-Form Health State Classification (SF-6D) [24, 25].

Treatment Evaluation

Treatment Preference and Evaluation

At baseline, participants recorded their preference for treatment (CBT4BN vs. CBTF2F) and rated credibility (i.e., how logical the proposed treatment appeared) and expectancy (i.e., how confident participants were that treatment would succeed) with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) [26]. At the end of treatment, they completed a 6-item self-report measure designed for this study that assessed their satisfaction with treatment.

Post-Treatment Service Utilization

Using the McKnight Follow-up of Eating Disorders (MFED) [27], participants were interviewed at 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up and reported whether they had psychotherapy for their eating disorder or had taken any psychotropic medications during the post-treatment period.

Randomization, Power, and Statistical Analyses

Details about randomization, power and statistical analyses have either been published previously or are described in Online Supplement: Methods [17, 18].

With a 15% margin, one-sided 95% confidence interval (CI), and expected 30% abstinence in the CBTF2F and CBT4BN group, we calculated power at 63% (PASS, version 11.00.10). This margin (d = 0.38) re-parameterized as an odds ratio and converted to Cohen’s d was used for all outcomes in the study to determine inferiority.

Analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1 and SAS 9.4. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) models were constructed for each primary, secondary, and tertiary outcome. Each model included a main effect term for treatment condition (CBT4BN and CBTF2F); a covariate term for site; dependent variables with a measure of baseline severity had baseline value included as a covariate term; a time main effect; and a treatment condition × time interaction term (end of treatment and follow up), which tested whether the effects of CBT4BN and CBTF2F differed over time. Results for the main hypothesis were interpreted with respect to the 95% CI of d and the non-inferiority margin (i.e., Cohen’s d = 0.38 instead of p values) [28].

Participants who did not provide data on abstinence were scored non-abstinent at the end of treatment, to conservatively estimate missing data on the primary outcome. Remaining missing data were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (MI) and maximum likelihood estimation with the expectation-maximization imputation (ML).

Results

The sample was somewhat diverse (6% African-American, 3% Asian, 1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 6% endorsing other, and 5% Latino) and 2% of the sample was male (Online Table 1). There were no significant differences between randomization groups on any baseline variables. Treatment completers had greater education and lower BMI than non-completers (Online Tables 1 & 2).

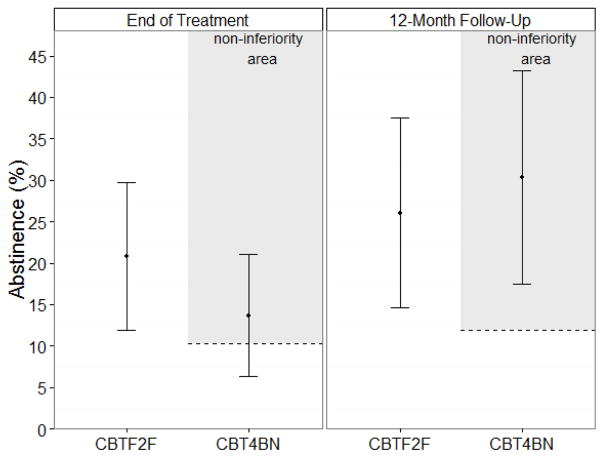

Table 1 and Online Table 3 give the results of the main analyses. Regarding the primary outcome, the percentage of abstinent participants increased from baseline to the end of treatment and from end of treatment to follow-up in both groups (Figure 1). At end of treatment, CBT4BN was inferior to CBTF2F but by the follow-up, CBT4BN was no longer inferior.

Table 1.

Comparison of online CBT (CBT4BN) to face-to-face CBT (CBTF2F) at end-of-treatment and 12-month follow-up for the treatment of bulimia nervosa: Multiple imputation analysis with the exception of abstinence at end of treatment (N = 179).

| End of treatment (95% Confidence Intervals) | 12-month follow-up (95% Confidence Intervals) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rater | da | lower | upper | result | da | lower | upper | result | |

| Primary Outcome | |||||||||

| Abstinence | Clinician | −0.18 | −0.47 | 0.11 | INFb | 0.07 | −0.22 | 0.37 | NIc |

|

| |||||||||

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||||

| BN symptoms | |||||||||

| Binge-eating frequency | Clinician | 0.06 | −0.23 | 0.36 | NI | 0.10 | −0.20 | 0.39 | INF |

| % Reduction in binge eating | Clinician | −0.01 | −0.29 | 0.29 | NI | 0.08 | −0.21 | 0.38 | NI |

| Purging frequency | Clinician | 0.02 | −0.27 | 0.31 | NI | −0.01 | −0.29 | 0.29 | NI |

| % Reduction in purging | Clinician | −0.04 | −0.33 | 0.26 | NI | 0.01 | −0.29 | 0.29 | NI |

| BN diagnosis | Clinician | 0.05 | −0.24 | 0.35 | NI | −0.01 | −0.30 | 0.28 | NI |

| Treatment acceptability | Self | −0.31 | −0.60 | −0.01 | INF | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||

| Tertiary Outcomes | |||||||||

| Eating Disorder Examination (Global Score) | Clinician | 0.04 | −0.25 | 0.33 | NI | −0.12 | −0.41 | 0.18 | NI |

| Body mass index | Self | −0.24 | −0.53 | 0.06 | NI | 0.01 | −0.28 | 0.31 | NI |

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Depressive disorder | Clinician | −0.11 | −0.40 | 0.18 | NI | −0.10 | −0.39 | 0.19 | NI |

| BDId | Self | −0.07 | −0.37 | 0.23 | NI | −0.10 | −0.40 | 0.21 | NI |

| Anxiety disorder | Clinician | 0.14 | −0.16 | 0.43 | INF | −0.04 | −0.33 | 0.25 | NI |

| BAIe | Self | 0.04 | −0.25 | 0.34 | NI | −0.17 | −0.46 | 0.12 | NI |

| EDQOLf | Self | 0.01 | −0.29 | 0.30 | NI | −0.08 | −0.38 | 0.21 | NI |

| SF-6Dg | Self | 0.04 | −0.25 | 0.33 | NI | 0.14 | −0.16 | 0.43 | NI |

| Treatment | |||||||||

| Failure to engage | NA | −0.24 | −0.53 | 0.05 | NI | ||||

| Dropout | NA | 0.20 | −0.09 | 0.49 | INF | - | - | - | - |

| Self-monitoring adherence | Self | −0.14 | −0.44 | 0.15 | INF | - | - | - | - |

Cohen’s d estimate;

Inferior;

Non-inferior;

Beck Depression Inventory;

Beck Anxiety Inventory;

Eating Disorders Quality of Life;

Short-Form Health State Classification.

When maximum likelihood produced the opposite substantive conclusion to multiple imputation this is noted with grey shading. Results for the main hypothesis were interpreted with respect to the upper (UCL) and lower (LCL) 95% confidence limits of d and the non-inferiority margin (i.e., Cohen’s d = 0.38 instead of p values). For outcomes whereby higher magnitude is desirable (i.e., abstinence, treatment acceptability), if the LCL is >−0.38 then CBT4BN is non-inferior, elsewise CBT4BN is inferior (e.g., abstinence at end of treatment, LCL is = −0.47, ∴ CBT4BN is inferior). For outcomes whereby lower magnitude is desirable (i.e., binge-eating frequency, BDI, EDQOL), if the UCL is < 0.38 then CBT4BN is non-inferior, elsewise CBT4BN is inferior (e.g., anxiety disorder at end of treatment, UCL is = 0.43, ∴ CBT4BN is inferior).

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants abstinent from binge eating and purging by therapy group [online CBT (CBT4BN) vs. face-to-face CBT (CBTF2F)] at the end-of-treatment and 12-month follow-up time points.a

aParticipants with missing data at the end-of-treatment time point are considered non-abstinent and missing data at 12-month follow-up are imputed using multiple imputation.

At baseline, CBT4BN was not inferior to CBTF2F on failure to engage in treatment; but was inferior on the rating of treatment preference and credibility. At the end of treatment, CBT4BN was not inferior to CBTF2F on percentage reduction in binge eating, major depression diagnosis, BDI, EDQOL, and SF-6D; but was inferior on treatment acceptability rating, treatment dropout, and self-monitoring adherence. At follow-up, CBT4BN was not inferior to CBTF2F on percentage reduction in binge eating, EDE, BMI, major depression diagnosis, BDI, BAI, and SF-6D; but was inferior on binge-eating frequency.

In terms of other factors that could have affected outcome, we compared reports of antidepressant usage at baseline and at post-treatment (~70% available data) and at post-treatment and follow-up (~50% available data), with no group difference on missingness. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in antidepressant use at any time points or in changes in use between time points. There were also no statistically significant differences between groups in psychotherapy use during the 12-month follow-up. Over the follow-up, 41% in CBT4BN and 58% in CBTF2F took antidepressant medication and 54% in CBT4BN and 47% in CBTF2F received psychotherapy.

Conclusions

CBT4BN was inferior to CBTF2F in producing abstinence from binge eating and purging at post-treatment, but by 12-month follow-up, was non-inferior on most measures. In both groups, symptom severity (as measured by the global EDE), comorbidity and general quality of life were improved, with CBT4BN non-inferior to CBTF2F at follow-up (with the exception of anxiety symptoms). Internet-based CBT may be a viable alternative intervention, that may be associated with a slower trajectory of change than CBTF2F in its current incarnation. Further study is needed, however, to examine why chat-based CBT resulted in a slower path to abstinence from binge eating and purging. We hypothesize that because of its inherent anonymity, chat-based therapy in CBT4BN may have led to fewer social demands for change than a face-to-face group during the trial. However during the follow-up period, participants in CBT4BN appeared to “catch up” to participants in CBTF2F. It might be that subsequent face-to-face interventions complemented CBT4BN more effectively than providing an extension to CBTF2F. Participants in CBT4BN might also have benefitted from easier access to the online manuals and worksheets during the follow-up period.

In absolute terms, the cognitive-behavioral treatment used in this study, whether delivered via CBT4BN or CBTF2F, only led to abstinence for a minority (14–30%) of participants. The majority were still symptomatic at the end of treatment and at follow-up. These abstinence rates mostly align with the previous RCT of this form of CBT (28% abstinence) [14]. However, previous RCTs of individual CBT have had greater success in achieving abstinence, with 38–47% of patients reporting abstinence by the end of 20-week treatment [17, 29, 30]. Our findings may represent an improvement over previous RCTs of group CBT, which reported 0–16% of participants abstinent by post-treatment, and only 10% at 6-month follow up [31–33]. Subsequent papers will examine treatment effectiveness by taking into account other individual characteristics associated with outcome (i.e., moderators) and explore potential adverse effects of psychotherapy [34, 35].

The high failure to engage and dropout rates in both conditions question the general acceptability of both interventions. Treatment augmentation, perhaps through individual visits, asynchronous email communication [36], text messages with therapists [37], and video conferencing [38], or intermittent face-to-face contact for on-line participants [16] may engage and retain patients for longer. More frequently scheduled groups and greater homework may also yield greater success [39].

In light of the present findings, placing CBT4BN within a system of clinical care requires careful consideration because improvement is slower. Although group CBT delivered through CBT4BN represents a parsimonious use of therapist time [7], the balance between the personal and economic costs and benefits needs investigation. CBT4BN (like CBTF2F) may represent an important intermediate step in a tiered treatment system that falls between self-help and individual CBT. Online therapy might also be more effective for patients with less comorbid psychopathology, and CBT4BN may be more suited for these individuals [16]. CBT4BN may have value as a treatment modality for patients who would otherwise be unable to access treatment due to long wait lists at specialist clinics, lack of mobility, or access to face-to-face CBT.

In the United States, for example, barriers for implementing chat group therapy include differences across state licensing boards and limitations on practicing across state boundaries [40]. Moreover, online medical services would need to meet strict federal privacy guidelines with clear protections and encryption of sensitive medical information [40]. Similar barriers exist with treatment across national borders and could be further compounded by language issues. In addition, there are significant ethical and legal concerns for treating participants remotely, particularly when patients experience suicidal ideation.

Secular trends in how adolescents and young adults (the peak age of risk for BN) [41] use technology have led to a decline in the use of online chat groups and a corresponding increase in communication through phones, particularly smartphones. In the U.S., although 55% of online adolescents reported going to web-based chat rooms in 2000, by 2006, this number had declined to 18% [42]. In contrast, in 2015, 91% of adolescents reported texting through a mobile app or website and 73% reported having their own smartphone [43]. Although texting in a group versus chat group conversations are functionally quite similar, it remains to be seen whether CBT4BN delivered through a mobile group text would be as effective as the web-based chat group described here.

Limitations and Strengths

Limitations of the present study include: power limitations for non-inferiority analyses, low inter-rater reliability for major depressive disorder, and high levels of dropout. However, this study represents the largest randomized controlled trial of chat group CBT for BN to date and one of only a few studies to examine the use of chat group technology in the treatment of mental illness [16].

Communication technologies, offer significant benefits for delivering psychotherapy including lowering barriers to access. However, as technological change outpaces research, clinicians need to examine both empirical evidence and legal guidelines before carefully deciding when, where, and to whom to deliver technologically-enhanced CBT for BN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant (R01MH080065), a Clinical Translational Science Award (UL1TR000083), and the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung. Dr. Zerwas is supported by a NIMH career development grant (K01MH100435). Drs. Peat and Runfola were supported by a NIMH post-doctoral training grant (T32MH076694). Dr. Runfola was supported by the Global Foundation for Eating Disorders (PIs: Bulik and Baucom; www.gfed.org). Benjamin Zimmer was supported by a Fellowship for Postdoctoral Researchers from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). Dr. Bulik acknowledges support from the Swedish Research Council (VR Dnr: 538-2013-8864). We wish to honor the incredible contribution and legacy of our colleague Dr. Robert Hamer, who passed away in December 2015.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Bulik is a grant recipient and consultant for Shire Pharmaceuticals and has consulted for Ironshore. Dr. Marcus is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Weight Watchers International, Inc. Dr. Peat is recipient of a contract from RTI and Shire Pharmaceuticals and has consulted for Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, L.E.K consulting, and Nexus Global Solutions. Dr Watson. is supported by a research grant from Shire awarded to UNC-Chapel Hill. Dr. Zerwas has consulted for L.E.K consulting.

Contributor Information

Stephanie C. Zerwas, Email: zerwas@med.unc.edu.

Hunna J. Watson, Email: hunna_watson@med.unc.edu.

Sara M. Hofmeier, Email: sara_hofmeier@med.unc.edu.

Michele D. Levine, Email: levinem@upmc.edu.

Robert M. Hamer, Email: hamer@med.unc.edu.

Ross D. Crosby, Email: rcrosby@nrifargo.com.

Cristin D. Runfola, Email: crunfola@stanford.edu.

Christine M. Peat, Email: christine_peat@med.unc.edu.

Benjamin Zimmer, Email: zimmer@psyres.de.

Markus Moessner, Email: moessner@psyres.de.

Hans Kordy, Email: hans.kordy@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

Marsha D. Marcus, Email: MarcusMD@upmc.edu.

Cynthia M. Bulik, Email: cbulik@med.unc.edu, cynthia.bulik@ki.se.

References

- 1.NICE. National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004. Http://www.Nice.Org.Uk/page.Aspx?O=101239. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay P, Bacaltchuk J, Stefano S. Psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000562.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Bulimia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:321–326. doi: 10.1002/eat.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzman MA, Bara-Carril N, Rabe-Hesketh S, Schmidt U, Troop N, Treasure J. A randomized controlled two-stage trial in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, comparing cbt versus motivational enhancement in phase 1 followed by group versus individual cbt in phase 2. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:656–663. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ec5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mussell MP, Crosby RD, Crow SJ, Knopke AJ, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. Utilization of empirically supported psychotherapy treatments for individuals with eating disorders: A survey of psychologists. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27:230–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<230::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crow S. The economics of eating disorder treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:454. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0454-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell J, Peterson C, Agras S. Cost effectiveness of psychotherapy for eating disorders. In: Miller N, editor. Cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy: A guide for practitioners, researchers, and policy makers. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 270–278. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez-Ortiz VC, House J, Munro C, Treasure J, Startup H, Williams C, Schmidt U. “A computer isn’t gonna judge you”: A qualitative study of users’ views of an internet-based cognitive behavioural guided self-care treatment package for bulimia nervosa and related disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16:93–101. doi: 10.1007/BF03325314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolemeyer R, Tietjen A, Kersting A, Wagner B. Internet-based interventions for eating disorders in adults: A systematic review. BMC psychiatry. 2013;13:207. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer S, Moessner M. Harnessing the power of technology for the treatment and prevention of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:508–515. doi: 10.1002/eat.22109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlegl S, Burger C, Schmidt L, Herbst N, Voderholzer U. The potential of technology-based psychological interventions for anorexia and bulimia nervosa: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:85. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loucas CE, Fairburn CG, Whittington C, Pennant ME, Stockton S, Kendall T. E-therapy in the treatment and prevention of eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melioli T, Bauer S, Franko DL, Moessner M, Ozer F, Chabrol H, Rodgers RF. Reducing eating disorder symptoms and risk factors using the internet: A meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49:19–31. doi: 10.1002/eat.22477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang C, Bazarova N, Hancock J. From perception to behavior: Disclosure reciprocity and the intensification of intimacy in computer-mediated communication. Communication Research. 2011;40:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golkaramnay V, Bauer S, Haug S, Wolf M, Kordy H. The exploration of the effectiveness of group therapy through an internet chat as aftercare: A controlled naturalistic study. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:219–225. doi: 10.1159/000101500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aardoom JJ, Dingemans AE, Spinhoven P, Van Furth EF. Treating eating disorders over the internet: A systematic review and future research directions. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:539–552. doi: 10.1002/eat.22135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulik C, Sullivan P, Carter F, McIntosh V, Joyce P. The role of exposure with response prevention in the cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:611–623. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulik CM, Marcus MD, Zerwas S, Levine MD, Hofmeier S, Trace SE, Hamer RM, Zimmer B, Moessner M, Kordy H. Cbt4bn versus cbtf2f: Comparison of online versus face-to-face treatment for bulimia nervosa. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1056–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulik C, Sullivan P, Carter F, Joyce P. Bulimia treatment study: Therapist manuals. Christchurch, New Zealand: University of Canterbury; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairburn C, Cooper Z. The eating disorders examination. In: Fairburn C, Wilson G, editors. Binge-eating: Nature, assessment and treatment. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 21.First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for dsm-iv-tr axis i disorders, research version, patient edition. (scid-i/p) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for beck depression inventory ii (bdi-ii) San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck A, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer R. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel S. Health related quality of life and disordered eating: Development and validation of the eating disorders quality of life instrument. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R, Thomas K. Deriving a preference-based single index from the uk sf-36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1115–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKnight Investigators. Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders in adolescent girls: Results of the mcknight longitudinal risk factor study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:248–254. doi: 10.1176/ajp.160.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothmann MD, Wiens BL, Chan IS. Design and analysis of non-inferiority trials. CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Wales JA, Palmer RL. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;166:311–319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poulsen S, Lunn S, Daniel SI, Folke S, Mathiesen BB, Katznelson H, Fairburn CG. A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:109–116. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polnay A, James VA, Hodges L, Murray GD, Munro C, Lawrie SM. Group therapy for people with bulimia nervosa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2241–2254. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen E, Touyz SW, Beumont PJ, Fairburn CG, Griffiths R, Butow P, Russell J, Schotte DE, Gertler R, Basten C. Comparison of group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:241–254. doi: 10.1002/eat.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones A, Clausen L. The efficacy of a brief group cbt program in treating patients diagnosed with bulimia nervosa: A brief report. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:560–562. doi: 10.1002/eat.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fava GA, Guidi J, Rafanelli C, Sonino N. The clinical inadequacy of evidence-based medicine and the need for a conceptual framework based on clinical judgment. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2015;84:1–3. doi: 10.1159/000366041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castellini G, Montanelli L, Faravelli C, Ricca V. Eating disorder outpatients who do not respond to cognitive behavioral therapy: A follow-up study. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2014;83:125–127. doi: 10.1159/000356496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ter Huurne ED, Postel MG, de Haan HA, DeJong CA. Effectiveness of a web-based treatment program using intensive therapeutic support for female patients with bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder and eating disorders not otherwise specified: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC psychiatry. 2013;13:310. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro JR, Bauer S, Andrews E, Pisetsky E, Bulik-Sullivan B, Hamer RM, Bulik CM. Mobile therapy: Use of text-messaging in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;43:513–519. doi: 10.1002/eat.20744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giel KE, Leehr EJ, Becker S, Herzog W, Junne F, Schmidt U, Zipfel S. Relapse prevention via videoconference for anorexia nervosa - findings from the restart pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:381–383. doi: 10.1159/000431044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKisack C, Waller G. Factors influencing the outcome of group psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:1–13. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199707)22:1<1::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeAngelis T. Practicing distance therapy, legally and ethically. APA: Monitor on Psychology. 2012;43:52. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zerwas S, Larsen JT, Petersen L, Thornton LM, Mortensen PB, Bulik CM. The incidence of eating disorders in a danish register study: Associations with suicide risk and mortality. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenhart A, Madden M, Smith A, MacGill A. Teens’ online activities and gadgets: Teens and Social Media. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenhart A. Teen, social media and technology overview 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.