Abstract

Almost 50% of children who visit the pediatric emergency department are exposed to tobacco smoke. However, pediatric emergency nurses do not routinely address this issue. The incorporation of a clinical decision support system into the electronic health record may improve the rates of tobacco exposure screening and interventions. We used a mixed-methods design to develop, refine, and implement an evidence-based clinical decision support system to help nurses screen, educate, and assist caregivers to quit smoking. We included an advisory panel of emergency department experts and leaders, and focus and user groups of nurses. The prompts include: 1) ASK about child smoke exposure and caregiver smoking, 2) ADVISE caregivers to reduce their child’s smoke exposure by quitting smoking, and 3) ASSESS interest and 4) ASSIST caregivers to quit. The clinical decision support system was created to reflect nurses’ suggestions, and was implemented in 5 busy urgent care settings with 38 nurses. The nurses reported that the system was easy to use, and helped them to address caregiver smoking. The use of this innovative tool may create a sustainable and disseminable model for prompting nurses to provide evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment.

Keywords: Clinical decision support systems, electronic health record, secondhand smoke, pediatrics, smoking cessation, smoking, nursing informatics

INTRODUCTION

There are over 25 million pediatric emergency department (PED) visits in the United States annually.1 Among children who visit the PED, up 48% of the caregivers smoke and children of these caregivers have high levels of tobacco smoke exposure (TSE).2,3 These caregivers are motivated to quit and are eager to receive cessation counseling in the PED.1,4–7 A recent Cochrane review showed the benefits and effectiveness of cessation advice given by registered nurses (RNs).8 PED RNs have the unique opportunity to educate caregivers about the health effects of TSE on their children and to provide caregivers with advice on quitting smoking as a way to reduce TSE.9,10 Prior work has demonstrated that RNs are willing to receive training so that they can provide tobacco treatment and TSE advice to caregivers and that RN-assisted tobacco counseling is accepted by staff and caregivers.11,12 However, PED RNs do not deliver TSE counseling in a systematic way due to barriers such as lack of training, time, and structured systems in intervening with adults.5,6,11,13–16

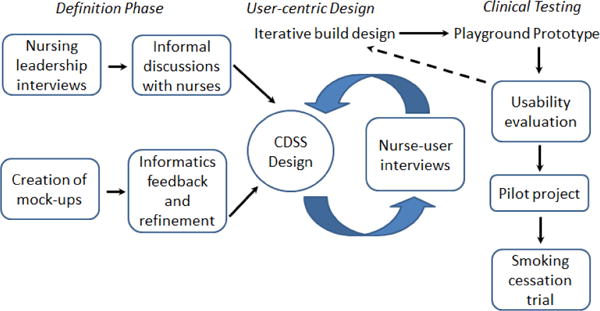

The use of electronic health records (EHRs) may provide a way to screen and provide tobacco treatment to caregivers who smoke. EHRs are installed in approximately 70% of United States hospitals.17 Included with these installations are computerized clinical decision support systems (CDSS). CDSS are “…designed to aid directly in clinical decision making, in which characteristics of individual patients are used to generate patient-specific assessments or recommendations that are then presented to clinicians for consideration.”18 CDSS include alerts, reminders, order sets, drug-dose calculations, or care summary dashboards that display performance feedback on quality indicators.18–21 CDSS can be used to improve preventive care, and increase guideline adherence, improve the care of patients, and reduce costs.19,20,22–26. Guidelines exist for successful implementation of CDSS.18,19 For a CDSS to be successful, it must be integrated in the dynamic environment of the healthcare setting.21 This technology must dynamically interact with practitioners, patients/caregivers, and existing healthcare systems.21,27,28 Providing the support in the right place, to the right person, at the right time, remains a challenge.29 Design challenges associated with the right place include integration with the users’ workflow. This can be done by involving users and allowing iterative development. To overcome challenges related to the right person, it is helpful to have end-users involved in the design of the system, thus producing more successful implementations.30 Finally, to ensure that obstacles associated with the right time are overcome, it is important to ensure that the final design has been usability tested, to increase adoption of the final product.31 The CDSS should then be introduced into clinical practice only after iterative formative evaluation, usability testing, and pilot field testing, designed to facilitate modifications based on user’s needs and the clinical environment (see Figure 1).28

Figure 1.

Conceptual design of the development of the smoking cessation clinical decision support system (CDSS).

The Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (CPGs),32,33 recommend that pediatric practitioners treat adult caregivers who smoke in all clinical encounters by using the EHR and “prompts” within a CDSS to: 1) “ASK” about and document tobacco use and TSE; 2) “ADVISE” all smokers to quit, and educate smokers that the only effective protection from TSE is to make their homes and cars smoke-free; and 3) “ASSESS” readiness to quit, and “ASSIST” in the attempt to quit. This approach targets the benefits of quitting on reducing the child’s TSE, and offers the potential to decrease tobacco-related morbidity in the caregiver and child. The expanded use of the EHR to prompt RNs to treat tobacco dependence has been used successfully in adult settings and provides a means to standardize screening and counseling of tobacco users in the PED.33–35 However, CDSS tools designed to facilitate TSE reduction have not been developed for use in the PED.

This article describes the development of a CDSS based on the empirically validated CPGs, which were adapted for use by in the pediatric setting. The CDSS was specifically aimed at pediatric nurses specializing in the care of children in the Urgent Care, which is an extension of the PED, at a large, tertiary care children’s hospital.

METHODS

Overview

The goal of the study was to develop and empirically evaluate a CDSS designed to encourage Urgent Care nurses to screen caregivers for tobacco use and provide brief tobacco cessation counseling. A mixed-methods evaluation design was used to develop the program components and test its feasibility and user acceptance. The study was conducted sequentially in two phases. Phase 1 consisted of the development of an alpha version of the CDSS with input from an expert panel; the alpha version was revised based on feedback from RNs in focus groups and focused interviews; this refined version was iteratively evaluated in small user groups of RNs in a test environment. A limited version of the alpha CDSS was tested in the live environment prior to launching the beta (prototype) full CDSS version. Additionally, we created feedback reports (FRs) to encourage the use of the CDSS prompts. The FRs were designed to inform RNs how frequently they performed the different tasks within the CDSS compared to their peers. We collected input on these FRs during the focus groups and user groups, and modified the FRs accordingly. During Phase 2, a pilot trial of the CDSS program was conducted. This article describes the results from Phase 1. The protocols for the advisory panel, focused interviews/groups, and usability testing were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board.

Setting

This study occurred at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), which is a 587-bed, freestanding, academic, pediatric medical center with more than 1.2 million patient encounters annually. This study was conducted in the Urgent Care setting, which is part of the emergency department. There are five separate Urgent Care sites with a total of over 50,000 visits annually. CCHMC uses an enterprise EHR system from Epic™ (Verona, WI). The EHR has been in use since 2009. The longitudinal EHR includes patient history, medications, order entry, exam reports, scanned documents, and all institutional-related visit information. The EHR is fully-integrated and all notes and orders are electronic.

Phase 1: Definition Phase

Advisory Panel

The first phase consisted of definition, development, and revision of the alpha version of the CDSS. The initial version was developed based on the CPGs and the AAP recommendations for treatment of tobacco use, and adapted by the research team which consisted of a PED physician (MMG), health psychologist (JSG) and biomedical informaticist (JWD).32,33,36 The initial prototype was revised based on the recommendations of an advisory panel (N=10) that consisted of PED nurse managers, clinical PED nurses, PED physicians, EHR analysts, and work-flow experts. The individuals reviewed the CDSS’ validity as an implementation of the CPG and AAP tobacco treatment guidelines, and provided guidance on content, the logistics of incorporation of the CDSS within the EHR, the potential impact on flow, and input on specific questions that the RNs should be asked during the development and iterative phases of the project.

CDSS Design

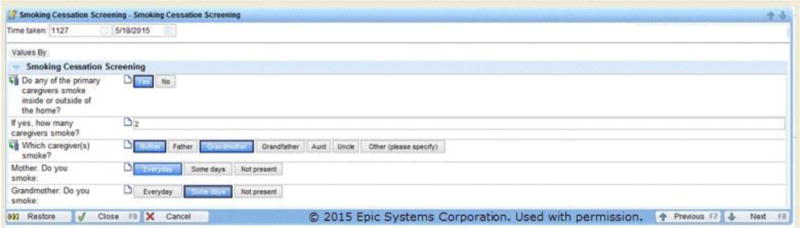

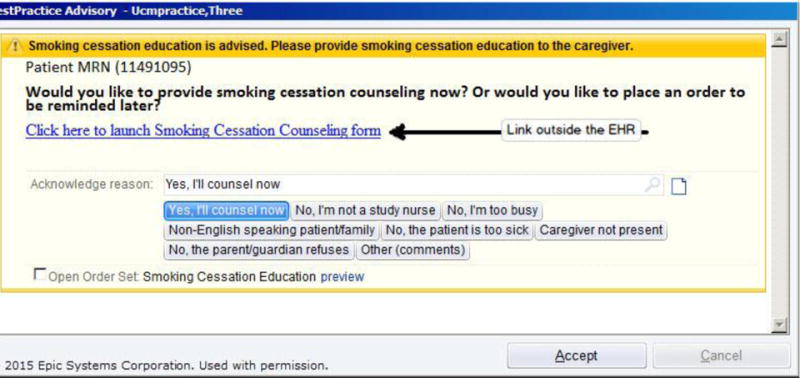

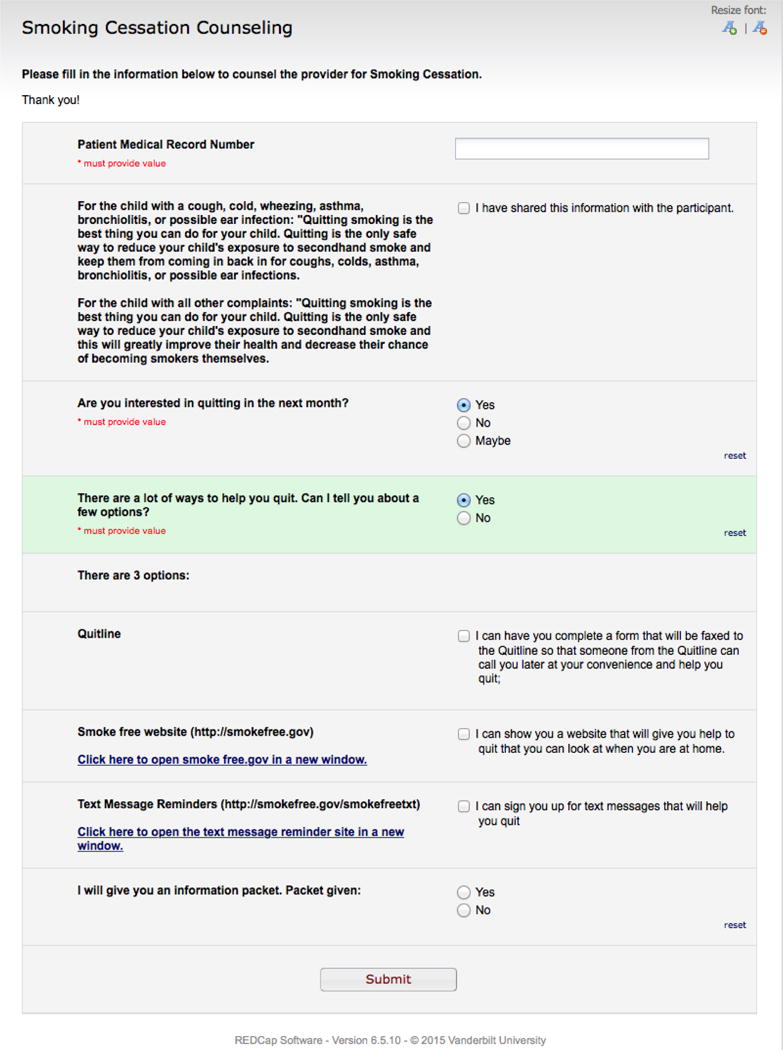

We used the feedback from the advisory panel to create mock-ups of each of the CDSS steps: (1) Tobacco use screening, or the “Ask” prompt (Figure 2), (2) a Best Practice Advisory (BPA) to recommend smoking cessation education once a caregiver who smokes was identified (Figure 3), (3) A link outside of the child’s EHR to direct the RN to the counseling prompts. This link led to a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database;37–39 (4) Prompts with brief instructions to “ADVISE” to quit, “ASSESS” readiness to quit, and “ASSIST” in quit attempts within REDCap (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Smoking Cessation Screening (i.e., “Ask”) prompt is used and the caregiver smokes. The RN may ask which caregiver(s) smokes, how often they smoke, and also if the caregiver is not present.

Figure 3.

Best Practice Advisory that reminded the RN to provide smoking cessation education; note the multiple options that the RN could select for providing or not providing counseling immediately.

Figure 4.

REDCap screenshot with the “ADVISE” and “ASSESS” prompts

Phase 1: User-Centric Design: Iterative Usability and Validity Testing.

Focus Groups and Focused Interviews

We recruited 10 clinical Urgent Care RNs to participate in small focus groups and focused interviews. Study procedures were explained and verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were told about the proposed CDSS, and encouraged to describe their current tobacco screening and counseling activities, how the proposed CDSS would fit into their workflow, and their attitudes and perceived barriers to providing tobacco cessation interventions to their patients’ caregivers. They were then shown printed mock-ups of the CDSS, and were asked to provide feedback on the best-fit workflow location for the prompts, and asked their views on the content, format, and language in each of the prompts. These mock-ups underwent iterative revisions during these focused interviews, were revised and printed, and then presented to additional nurses until saturation of ideas and comments was achieved.

User Groups, User Interviews, and Usability Testing

After the alpha CDSS was created and refined, it was entered into a test environment by the Epic build team. Our study team made modifications to the CDSS within the test environment to ensure that we addressed all of the RN input from the focused interviews. We then recruited 10 additional RNs to participate in several small user groups and individual user interviews to assess CDSS usability. Study procedures were explained and verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Study staff had participants log into the CDSS and perform smoking cessation screening in the testing environment. Usability testing consisted of each RN using the CDSS during hypothetical patient Urgent Care visits presented in the testing environment while study staff recorded the interactions. The usability testing combined three sources of data: 1) notes taken during observation, 2) a think-aloud protocol in which RNs were asked to describe what they were doing, why, and what their thoughts were; and 3) a modified survey of the system usability scale in which RNs were given specific questions to assess prompt usability and acceptability.40 The system usability scale questions were modified to be specific to the implementation of our CDSS (e.g., ease of use link from Epic to REDCap, ease of use link to online cessation resources. See Table 1). We gave RNs specific questions to assess independent thematic aspects related to the CDSS and prompts, including: 1) functionality, 2) content, 3) number of “clicks”, 4) length, 5) appearance, format, and type, 6) ease of use, 7) time to use, 8) linkage from the EHR to REDCap, 9) linkage to cessation materials, 10) linkage to smokefree.gov, SmokefreeTXT, 11) integration with regular PED workflow, 12) technical support and training required, 13) perception of maintenance of use and sustainability, and 14) acceptability of FRs. Validity was addressed by one investigator (JSG), who was not present at these sessions, who reviewed and compared the results across participants. Following these analyses, we developed a list of design changes that were then incorporated into the revised CDSS and used in subsequent rounds of usability testing.

Table 1.

Mean scores of different thematic aspects of the CDSS* assessed of the user group nurses (N=10)

| Questions related to CDSS that were assessed | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Easy to use (Scale: 1, not at all easy – 5, very easy) | 4.1 (0.99) |

| Useful in helping address smoking with caregivers (Scale: 1, not at all useful – 5, very useful) | 4.5 (0.71) |

| Amount of information on REDCap (Scale: 1, too much – 3, not enough) | 1.9 (0.57) |

| Total number of clicks to use CDSS (Scale: 1, too many – 3, too few) | 1.9 (0.35) |

| Simple and clear design of CDSS (Scale: 1, not at all simple – 5 very simple) | 4.0 (0.94) |

| Length of time to use CDSS (Scale: 1, too long – 3, too short) | 3.2 (1.73) |

| Easy to use link from Epic to REDCap (Scale: 1, hard to use – 5 easy to use) | 3.7 (1.2) |

| Easy to use link to online cessation resources (Scale: 1, hard to use – 5, easy to use) | 4.6 (0.97) |

| How easily the CDSS will fit into the Urgent Care workflow (Scale: 1, not at all easy – 5, very easily) | 3.9 (0.88) |

| Training and support prepared use of the CDSS (Scale: 1, not at all well – 5, very well) | 4.4 (0.84) |

| Likely to continue using CDSS in daily Urgent Care workflow (Scale: 1, not at all likely – 5, very likely) | 4.2 (0.92) |

| Usefulness of the feedback reports (Scale: 1, not at all useful – 5 very useful). | 4.4 (0.79) |

CDSS: Clinical Decision Support System

Following these user sessions, we performed a two-month pilot study of the screening portion of the CDSS to assess feasibility and workflow integration.

Measures

The 20 RNs who participated in the focus and user groups completed a questionnaire with items that assessed sociodemographics, prior tobacco use history, current tobacco control practices, and attitudes and perceived barriers towards providing tobacco cessation education and interventions in the UC setting. Questionnaire items were adapted from similar surveys used in previous studies.11,41,42 The questionnaire consisted of 16 items assessing current tobacco cessation behaviors (based on the “5 A’s” model), 6 items regarding attitudes toward providing tobacco cessation services to parents, and 11 items measuring barriers to providing tobacco interventions.

RESULTS

Focus and User Group Participant Characteristics

Demographics and Prior Tobacco Use History

A total of 20 RNs participated in the focus interviews/groups and user testing. All respondents were female; the mean age (standard deviation) was 37.20 (9.16) years old; 20 (100%) were Caucasian. The majority of subjects (70%) had been in practice for over 5 years. Fifteen (75%) reported that they had never smoked, 2 (10%) said they had experimented with smoking, 2 (10%) were former smokers, and no one reported being regular or occasional smokers (one (5%) did not respond to this question); none had ever used smokeless tobacco.

Tobacco Control Practices

Eleven (55%) respondents indicated that they assessed caregivers’ smoking status, 12 (60%) documented caregivers’ tobacco use on the pediatric chart, and 11 (55%) reported that they encouraged caregivers who smoke to quit. Even fewer respondents indicated that they provided specific counseling or assistance to their patient’s caregivers interested in quitting. For example, 18 (90%) respondents reported that they had never helped caregivers to set a quit date, and 18 (90%) reported that they had never given self-help materials to assist in tobacco cessation. Furthermore, only one respondent had ever recommended pharmacotherapy.

Attitudes and Barriers Toward Tobacco Cessation Education and Interventions

Six (30%) respondents indicated that they were somewhat to very interested in learning more effective techniques to help caregivers quit smoking; 7 (35%) reported that RNs should advise caregivers to quit; and 7 (35%) reported that RNs can be effective in helping patients’ caregivers to quit smoking. Respondents reported that lack of caregiver materials, lack of referral resources, and caregiver resistance were the three most significant obstacles to providing tobacco cessation interventions to their patients’ caregivers.

CDSS Content and Workflow

Location of Screening Prompts

Results from the focused interview/group testing indicated that the screening prompt should be placed in the nursing documentation section in between recent travel history and the airway/breathing/circulation assessment. However, once the prompt was placed in the test environment, the user group nurses determined that the prompt should be placed after chief complaint and emergency department notes. They felt that this location worked well with their workflow because they ask chief complaint as part of their initial assessment.

Content of Screening Prompts

The screening prompt was changed from the existing prompt which was “Tobacco/Smoke Exposure” located in the social history portion of the EHR. The final screening prompt was changed to: “Do any of the primary caregivers smoke inside or outside of the home?” These changes were made to appropriately identify caregivers who were smokers but did not consider their child exposed to SHS (because they did not smoke in the home). Additionally, we accommodated for the presence and identification of multiple caregivers who smoked, and assessed whether they were “Everyday” or “Someday” smokers (see Figure 2). In total, the screening prompt underwent 5 iterations. The RNs also requested that we account for the presence of other smokers in the child’s home who were not the caregivers. Thus, the screening prompt included questions to identify other smokers in the home who were not caregivers. Finally, the screening prompt was set to account for caregivers who smoked but were not present at the visit. All these screeners were used so that appropriate materials could be given.

Content of Best Practice Advisory (BPA)

The RNs were asked how they would like to be led into the “Advise” step. RNs were in favor of a BPA, an interruptive, pop-up alert that would display once they completed the screening prompt. This alert appeared in yellow at the top of the patient’s EHR. Initially, this prompt read: “Smoking cessation education is advised. Please provide smoking cessation education to the caregiver.” The RNs requested that we change this so that a question was posed to the RNs with options to provide the counseling now or later, with a reminder order placed for the RN. Thus, the prompt was changed to: “Would you like to provide smoking cessation counseling now? Or would you like to place an order to be reminded later?” The RNs requested that the BPA contain multiple opt-out reasons that they could select so that they did not have to complete counseling (See Figure 3). For those RNs who felt that they may be too busy to complete the counseling steps right after screening was done, we created an option for them to select a checkbox that allowed for the population of a reminder order for “Smoking Cessation Education.” When this option was selected, the RN had to sign off on the order, and then they could complete the counseling at a later time. This order would lead them to the same “ADVISE”, “ASSESS” and “ASSIST” prompts that the RNs completed if they opted to counsel right away.

Link outside of the EHR

The advisory panel and focus groups felt strongly that the counseling prompts should not be present in the child’s EHR. Thus, we placed a link that would lead the RNs to REDCap, the external, online, research database to access the counseling prompts.37–39 This link launched REDCap from an integrated EHR link through either the BPA reminder or within the reminder order. A text-based link was also provided to the RNs to trigger the cessation education prompts.

Cessation Education Prompts

Within REDCap, we included the “ADVISE”, “ASSESS”, and “ASSIST” prompts. For ADVISE, RNs were prompted to advise all caregivers to quit smoking for the health of their children; however, if a child came in for a TSE-related illness (e.g., cough, cold, wheezing), RNs were also prompted to advise the caregiver that if they quit, it may decrease the number of times that their child came in for these types of illnesses. The RN was then taken to the “ASSESS” step (Figure 4) which included branching logic. If a caregiver was not interested in quitting in 30 days, the RN was prompted to convey understanding that the caregiver wasn’t interested in quitting, and to offer an information packet. For those caregivers who were interested in quitting, the RN was presented with the “ASSIST” prompt to give caregivers the option to connect to the Tobacco Quitline, smokefree.gov, or SmokefreeTXT.43–45

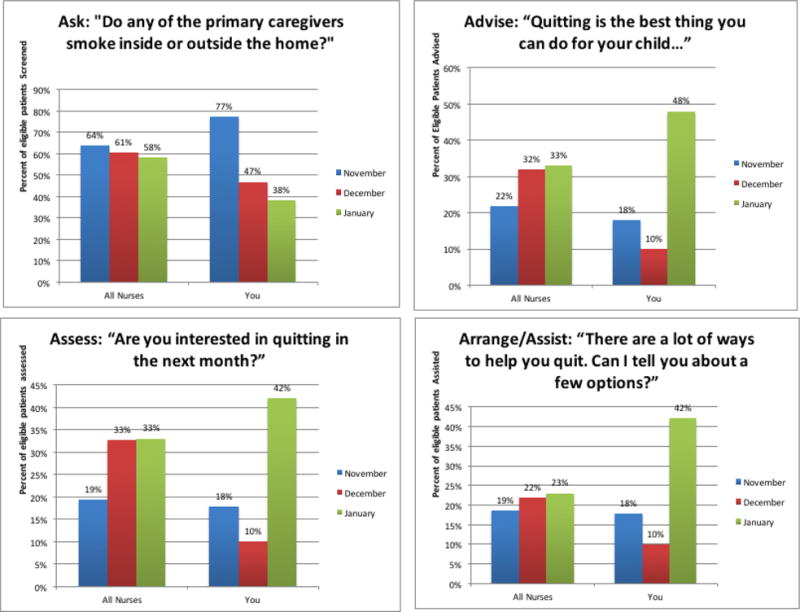

Feedback Reports (FRs)

Based on the work of Bentz, et al, we created FRs that were to be given at the beginning of each month.34 The FRs contained current and historical data to show the individual RN and overall RN compliance with the “ASK”, “ADVISE”, “ASSESSS”, and “ASSIST” steps. Each RN’s FR included a comparison of individual performance to the overall performance average of all of the study RNs.34,46 RNs were assured that only the study team would have access to the FRs, and each RN would have access only to their own report. Our goal was to provide three monthly FRs to each RN via their personal email; FRs would not be used to judge clinical performance. Using focus group procedures employed in our previous research,47 we showed RNs hardcopy mock-ups of the FRs, and solicited their feedback for use in refining the content and format. RNs were given mock-ups on paper of the FRs which there were asked to assess and give us feedback on.48,49 RNs said that they preferred bar graphs of each of the CDSS steps, and they agreed with placing their performance next to all of the study RNs’ performance. Figure 5 illustrates two month FR mock-ups.

Figure 5.

Mock-up of monthly feedback reports for nursing staff.

Usability Testing

We assessed usability of the CDSS and feedback reports with 10 RNs. As shown in Table 1, RNs reported that the CDSS was easy to use (mean = 4.1), and would be very useful in helping to address smoking with caregivers (mean = 4.5). The RNs reported that using the CDSS would easily fit into their workflow (mean = 3.9), and that they would be likely to use it daily (mean = 4.2). Finally, the user testers found the feedback reports helpful (mean = 4.4). Comments from the RNs included: “…this seems very user friendly”; “…this seems pretty quick and simple”; “Can we have a prompt that will allow us to provide information for those children whose parents smoke but they aren’t present at the visit?”; and “Can we provide information for other family members or others who take care of the child even if the parent doesn’t smoke?”

Screening Pilot

Finally, we conducted a pilot phase for two months during which only the screening portion of the CDSS was tested in the EHR. While we were recruiting and training RNs for the Phase 2 pilot study, we rolled out the screening prompt in the live Epic environment. Once live, the screening prompt was available for use by all RNs (not just study participants who were trained). The additional prompts and counseling packets were not available.

We evaluated the frequency of the use of the screening prompt by RNs who were enrolled in the study between 9/1/2015 – 10/31/2015, (N=38), as well as among RNs who were not enrolled in the study (N=16). Study RNs used the screening prompt during 4,572/9,509 (48%) of the total visits, and identified 984 (21.5%) one of more primary caregivers who smoked. The prompt was used during 246/2,235 (11%) of the 2,235 total visits by non-study RNs, who identified 33 (13.4%) one or more primary caregivers who smoked.

We asked study RNs if they experienced any issues or problems while using the screening prompts. Common themes identified by the RNs included their desire to access and use the counseling portions of the CDSS, use of the screening prompt as an opportunity to discuss secondhand smoke exposure, identification of both cigarette smoking and marijuana use, and appreciation for the CDSS and a new tool to help them address tobacco use.

Discussion

We followed best-practice informatics recommendations during the development of a CDSS to assist RNs in the Urgent Care setting to screen caregivers for tobacco use and counsel them to stop smoking.18,19 The goal was to improve the health of both the caregiver and their child. We adapted the CPGs and the AAP’s recommendations for tobacco screening and counseling.32,36 These recommendations encourage practitioners to perform the five “A’s”: “Ask” about tobacco use, “Advise” tobacco users to quit, “Assess” readiness to quit, “Assist” in quit attempts, and “Arrange” for follow-up.32 The AAP endorses the 5 A’s approach and also recommends that practitioners provide information to caregivers on the effects of TSE on their child’s health. Our goal was to create and provide work flow integrated prompts within the CDSS that would facilitate screening, counseling, and arrangement of follow-up that would be easily integrated into the RNs’ workflow. Since this was a CDSS geared towards RNs, we sought to create prompts that would guide RNs to encourage caregivers to quit smoking to improve their child’s health in clear, non-threatening language, and to facilitate referral of caregivers to outside resources. We did not design the CDSS to guide RNs in recommending specific pharmacotherapy since they would not be the prescribing practitioner. Our work is similar to that of a prior study which modified the pediatric primary care EHR to include prompts to facilitate counseling and referral to the QL for caregivers who smoke.50 In this study, when a smoker was identified using their existing screening prompt, a new question was added to “Assess” interest and timeline in quitting and then based on the response, an educational handouts and/or a QL referral was facilitated. Our results are also similar to those contained in a Cochrane review that evaluated the use of EHRs to support smoking cessation. This review showed that documentation and referral to tobacco cessation counseling increased when an EHR was in place.51

We employed a multi-phase development process which included development of the prototype, iterative refinement with an expert panel, small focus groups and focused interviews to further refine the CDSS with RNs, iterative usability testing with RNs. The data obtained before we started developing the CDSS demonstrated that RNs did not screen caregivers for tobacco use in a routine fashion or feel comfortable screening and providing cessation advice. Therefore, our screening pilot data is particularly promising. It showed that the RNs screened caregivers during almost 50% of the visits even though the complete CDSS had not yet been implemented. Our next steps will be to pilot test the full CDSS in the urgent care setting. These results will be described in a subsequent paper.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health CA184337 (Dr. Mahabee-Gittens and Dr. Gordon)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf.

- 2.Mahabee-Gittens EM, Khoury JC, Ho M, Stone L, Gordon JS. A smoking cessation intervention for low-income smokers in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(8):1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melinda Mahabee-Gittens E, Gordon JS. Missed opportunities to intervene with caregivers of young children highly exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke. Prev Med. 2014;69:304–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahabee-Gittens EM, Gordon J. Acceptability of tobacco cessation interventions in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(4):214–216. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31816a8d6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahabee-Gittens EM, Gordon JS, Krugh ME, Henry B, Leonard AC. A smoking cessation intervention plus proactive quitline referral in the pediatric emergency department: a pilot study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(12):1745–1751. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahabee-Gittens EM, Huang B. ED environmental tobacco smoke counseling. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(7):916–918. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahabee-Gittens M. Smoking in parents of children with asthma and bronchiolitis in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18(1):4–7. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice VH, Stead LF. Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2004;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub2. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub2/epdf. Published January 26, 2004. Accessed October 22, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Tingen MS, Waller JL, Smith TM, Baker RR, Reyes J, Treiber FA. Tobacco prevention in children and cessation in family members. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18(4):169–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randall S. Children and secondhand smoke: not just a community issue. Paediatr Nurs. 2006;18(2):29–31. doi: 10.7748/paed2006.03.18.2.29.c1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deckter L, Mahabee-Gittens EM, Gordon JS. Are pediatric ED nurses delivering tobacco cessation advice to parents? J Emerg Nurs. 2009;35(5):402–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollis JF, Lichtenstein E, Vogt TM, Stevens VJ, Biglan A. Nurse-assisted counseling for smokers in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):521–525. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein SL, Bijur P, Cooperman N, et al. A randomized trial of a multicomponent cessation strategy for emergency department smokers. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(6):575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bock BC, Becker BM, Niaura RS, Partridge R, Fava JL, Trask P. Smoking cessation among patients in an emergency chest pain observation unit: outcomes of the Chest Pain Smoking Study (CPSS) Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(10):1523–1531. doi: 10.1080/14622200802326343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boudreaux ED, Baumann BM, Perry J, et al. Emergency department initiated treatments for tobacco (EDITT): a pilot study. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(3):314–325. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geller AC, Brooks DR, Woodring B, et al. Smoking cessation counseling for parents during child hospitalization: a national survey of pediatric nurses. Public Health Nurs. 2011;28(6):475–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charles D, Gabriel M, Furukawa M. Adoption of electronic health record systems among US non-federal acute care hospitals: 2008–2013. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2014. (ONC Data Brief: No. 16). http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/oncdatabrief16.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–1238. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumenthal D, Glaser JP. Information technology comes to medicine. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2527–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr066212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcy TW, Kaplan B, Connolly SW, Michel G, Shiffman RN, Flynn BS. Developing a decision support system for tobacco use counselling using primary care physicians. Informatics in primary care. 2008;16(2):101–109. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i2.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):29–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998;280(15):1339–1346. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams ES, Longhurst CA, Pageler N, Widen E, Franzon D, Cornfield DN. Computerized physician order entry with decision support decreases blood transfusions in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1112–1119. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiks AG, Hunter KF, Localio AR, et al. Impact of electronic health record-based alerts on influenza vaccination for children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):159–169. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, et al. Text4Health: impact of text message reminder-recalls for pediatric and adolescent immunizations. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):e15–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wears RL, Berg M. Computer technology and clinical work: still waiting for Godot. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1261–1263. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hesse BW, Shneiderman B. eHealth research from the user’s perspective. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sirajuddin AM, Osheroff JA, Sittig DF, Chuo J, Velasco F, Collins DA. Implementation pearls from a new guidebook on improving medication use and outcomes with clinical decision support. Effective CDS is essential for addressing healthcare performance improvement imperatives. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2009;23(4):38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ives B, Olson MH. User Involvement and Mis Success - a Review of Research. Manage Sci. 1984;30(5):586–603. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mainthia R, Lockney T, Zotov A, et al. Novel use of electronic whiteboard in the operating room increases surgical team compliance with pre-incision safety practices. Surgery. 2012;151(5):660–666. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Human Services; 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyle RG, Solberg LI, Fiore MC. Electronic medical records to increase the clinical treatment of tobacco dependence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6 Suppl 1):S77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, et al. Provider feedback to improve 5A’s tobacco cessation in primary care: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(3):341–349. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linder JA, Rigotti NA, Schneider LI, Kelley JH, Brawarsky P, Haas JS. An electronic health record-based intervention to improve tobacco treatment in primary care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):781–787. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Committee on Environmental Health, Committee on Substance Abuse, Committee on Adolescence, Committee on Native American Child. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: Policy statement–Tobacco use: a pediatric disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1474–1487. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glenn B. Why Epic’s market dominance could stifle AEHR and health IT innovation. Med Econ. 2013 http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/why-epics-market-dominance-could-stifle-ehr-and-health-it-innovation. Published April 25, 2013. Accessed October 22, 2015.

- 39.Epic EMR [computer program] Verona, WI: Epic Systems Corporation; [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooke J. SUS: A ‘quick and dirty’ usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, McClelland IL, Weerdmeester B, editors. Usability Evaluation In Industry. Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis; 1996. pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon JS, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Severson HH, Akers L, Williams C. Ophthalmologists’ and optometrists’ attitudes and behaviours regarding tobacco cessation intervention. Tob Control. 2002;11(1):84–85. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.1.84-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albert DA, Severson H, Gordon J, Ward A, Andrews J, Sadowsky D. Tobacco attitudes, practices, and behaviors: a survey of dentists participating in managed care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S9–18. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smokefree.gov. http://smokefree.gov/. Accessed October 22, 2015.

- 44.SmokefreeTXT. http://smokefree.gov/smokefreetxt. Accessed October 22, 2015.

- 45.Ohio Tobacco Quit Line. https://ohio.quitlogix.org/. Accessed October 22, 2015.

- 46.Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, Person SD, Weaver MT, Weissman NW. Improving quality improvement using achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2871–2879. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon JS, Mahabee-Gittens EM. Development of a Web-based tobacco cessation educational program for pediatric nurses and respiratory therapists. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2011;42(3):136–144. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20101201-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnall R, Rojas M, Bakken S, et al. A user-centered model for designing consumer mobile health application (apps) J Biomed Inform. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin HW, Wang YJ, Jing LF, Chang P. Mockup design of personal health diary app for patients with chronic kidney disease. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;201:124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharifi M, Adams WG, Winickoff JP, Guo J, Reid M, Boynton-Jarrett R. Enhancing the electronic health record to increase counseling and quit-line referral for parents who smoke. Academic pediatrics. 2014;14(5):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2011;(12):CD008743. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008743.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]