Introduction

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a multi-domain cytosolic protein that belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix/Per-Arnt-Sim (bHLH/PAS) family of transcription factors. Ligand binding induces a conformational change in AHR and promotes nuclear translocation of the receptor (Kewley et al. 2004). AHR can either bind to exogenous (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins, cigarette smoke) or endogenous ligands (arachidonic acid and leukotrienes, heme metabolites, UV photoproducts of tryptophan) within the cytoplasm. Exogenous ligands such as 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and 3-methylcholanthrene are known to activate AHR and mediate cellular toxic response. AHR is also activated by dietary compounds including indole-3-carbinol and flavonoids that mediate various physiological activities in the body (Nguyen and Bradfield 2008; Marconett et al. 2010). AHR ligands are classified as agonists and antagonists depending on the ability of ligands to activate or inhibit AHR induced activity. Previous reports indicate that ligands such as kaempferol, resveratrol, galangin, chrysin and quercetin act either as agonists or antagonists based on the ligand concentration and type of cells induced (Zhang et al. 2003). Thus, diversity of ligands makes AHR signaling a very dynamic and complex.

AHR in its inactive state is located in the cytoplasm and forms a complex with molecular chaperones, such as heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and co-chaperons such as p23 and AHR-interacting protein (AIP) (Trivellin and Korbonits 2011). In presence of ligand, AHR undergoes nuclear translocation where it interacts with AHR nuclear transporter (ARNT) or AHR repressor (AHRR) through the PAS domain. It has been reported that nucleocytoplasmic transport mechanism of AHR varies between humans and mice. In humans, AHR both in stimulated or unstimulated state can undergo nuclear translocation complexed with AIP. In contrast, association of AIP prevents nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of AHR in mice in both stimulated and unstimulated states (Ramadoss et al. 2004). Once AHR is translocated to the nucleus it forms a heterodimer complex with ARNT and binds to xenobiotic response elements located in the promoter region of the target genes. This complex induces coordinated transcription of detoxifying enzymes for efficient absorption, distribution and elimination of xenobiotics from the body (Abel and Haarmann-Stemmann 2010). Apart from this, AHR is known to exhibit endogenous functions such as cell proliferation, cell differentiation and apoptosis. It also acts as an endogenous regulator in several developmental and physiological processes including neurogenesis, hematopoietic stem cell regulation, cellular stress response, immunoregulation and reproductive health (Lindsey and Papoutsakis 2012; Kadow et al. 2011; Hansen et al. 2014).

AHR is associated with various pathological and physiological disorders in the body including autoimmune diseases (Veldhoen et al. 2008), inflammation (Podechard et al. 2008; Ovrevik et al. 2014), cardiovascular diseases (Kerley-Hamilton et al. 2012; Savouret et al. 2003) and cancer. Activation of AHR in presence of cigarette smoke has been well documented in lung cancer (Martey et al. 2005; Tsay et al. 2013). Cigarette smoke induced AHR is also known to mediate immune signaling mechanism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Chen et al. 2011). Apart from playing an essential role in COPD and lung cancer, AHR expression has been reported in other cancers and adenomas. AHR is reported to be downregulated in growth hormone secreting pituitary adenomas (Jaffrain-Rea et al. 2009), while, increased expression levels of AHR are associated with tumorigenesis in medulloblastoma (Dever and Opanashuk 2012). The enhancement of AHR levels under ligand stimulation induced cell cycle arrest has been reported in pancreatic and gastric cancer (Koliopanos et al. 2002; Peng et al. 2009). Depending upon the type of ligand stimulation, AHR is either known to promote or inhibit tumor progression. Stimulation of AHR with TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzofuran and 3,3′-diindolylmethane inhibits invasiveness and cell growth in breast cancer (Hall et al. 2010). In contrast, stimulation of AHR with n-butyl benzyl phthalate and dibutyl phthalate ligands enhances tumorigenic properties in breast cancer cells (Hsieh et al. 2012). Therefore, AHR could serve as a potential therapeutic target in several cancers (Murray et al. 2014) and hence it is important to develop AHR signaling pathway to understand the mechanism of AHR mediated tumor progression and regression. Although, the diverse role of AHR is documented in literature however a detailed network of AHR signaling is lacking. In this study, we have curated literature information pertaining to AHR induced signaling and developed a pathway map to facilitate better understanding of this receptor.

Materials and methods

Literature searches were carried out in PubMed with key terms including ‘aryl hydrocarbon receptor’ and ‘AHR signaling’. Information pertaining to protein-protein interactions (PPIs), post-translational modifications (PTMs), activation/inhibition reactions, protein transport and gene expression events were curated from papers, which described those experiments as described earlier (Radhakrishnan et al. 2012; Nanjappa et al. 2011). These reactions were included under AHR stimulation by exogenous and/or endogenous ligands. We followed NetPath annotation criteria as described previously (Kandasamy et al. 2010) to capture AHR signaling reactions. The entries were added into ‘PathBuilder’, an annotation tool developed in-house for the manual annotation of signaling events (Kandasamy et al. 2009). Gene expression data was curated from experiments, which used only human cells in both normal and diseased conditions. The data was uploaded to NetPath after a series of manual curation and review processes. We also incorporated the suggestions provided by an expert in the field (pathway authority) in order to enhance confidence of the documented signaling events. The reactions were then used to generate AHR signaling pathway map using ‘PathVisio’ (http://www.PathVisio.org) (van Iersel et al. 2008).

Data formats and availability

We have made the pathway information for AHR signaling available in NetPath. The signaling pathway information is compatible with various international data exchange formats. This includes Proteomics Standards Initiative for Molecular Interaction (PSI-MI) (Hermjakob et al. 2004), Biological PAthway eXchange (BioPAX level 3) (Demir et al. 2010) and Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML 3) (Hucka et al. 2003). These formats ensure interoperability with pathway analysis software tools such as Cytoscape and Ingenuity pathway analysis. The data for AHR signaling pathway can be downloaded in the above mentioned formats from NetPath (http://www.netpath.org).

Results and discussion

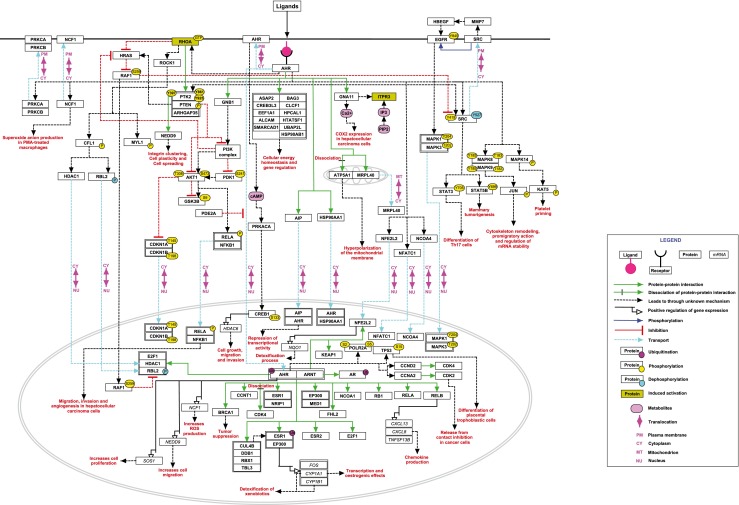

Over 3000 articles were screened from PubMed that are related to AHR signaling in response to exogenous or endogenous ligands. A total of 88 proteins were curated that are experimentally proven to be involved in AHR signaling cascade. These 88 proteins were found to participate in 49 PPIs, 37 PTMs, 21 translocation events, 4 activation/inhibiton reactions. In addition, 17 site-specific PTMs were catalogued of which, sites and residues were mapped to RefSeq accessions for 13 proteins. Further, 311 differential gene expressions were documented in response to AHR-ligand stimulation. We have submitted the AHR pathway data to NetPath at http://www.netpath.org/pathways?path_id=NetPath_164. The web page for AHR pathway in NetPath provides a brief description of AHR signaling pathway, molecule and reaction statistics of the pathway and different downloadable formats. Every molecule documented in NetPath is linked to a molecular page. To facilitate additional information on the curated data and provide it in an user friendly manner, molecular pages have been linked to external protein resources including NCBI RefSeq, Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) (Prasad et al. 2009), Entrez gene (Maglott et al. 2011), Swiss-Prot (Boeckmann et al. 2003) and OMIM databases (Hamosh et al. 2005). A pictorial representation of AHR signaling map is shown in Fig. 1. Data presented in NetPath pertaining to this pathway will be periodically updated.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of AHR signaling pathway. The pathway map represents reactions of AHR signaling pathway that are documented in NetPath. Different types of reactions and molecules are distinguished with different colors and arrows as provided in the legend

AHR along with chaperones remains in the cytoplasm in a dormant state. The signaling cascade initiating from ligand binding to transcription of target genes involves various co-activators and chaperones. HSP90, AIP and p23 are some of the molecules that are known to interact with AHR in the cytoplasm. AIP interacts with both AHR and HSP90 through its tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains. Mutations in AIP affect the structural integrity of TPR domain and disrupt the binding of AHR to AIP, causing AHR destabilization and degradation (Morgan et al. 2012; Lees et al. 2003). Previous reports have also shown that AIP mutation leads to growth hormone secreting pituitary adenomas with increased IGF1 levels and reduced ARNT levels leading to pituitary tumorigenesis (Raitila et al. 2010, Heliovaara et al. 2009). AIP remains bound to AHR even under ligand induced state without hampering shuttling across nuclear membrane and represses its associated transcriptional activity (Ramadoss et al. 2004). In addition to AIP, HSP90 is also known to translocate from cytosol to nucleus complexed with AHR under ligand stimulated condition (Tsuji et al. 2014). Within the nucleus, ARNT facilitates the displacement of HSP90 from the complex resulting in the formation of AHR-ARNT heterodimer. AHR-ARNT dimer binds to the DNA sequences and mediates the recruitment of multiple co-activators, which helps in the transcriptional regulation of a number of genes. These includes a cascade of detoxifying enzymes such as phase I enzymes, the phase II enzymes, the phase III transporters and solute carrier family proteins (Xu et al. 2005). Phase I enzymes are monooxygenases, which includes xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochrome P450 group of proteins while phase II enzymes include NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) and glutathione S-transferase (GST). Increased gene expression of phase I and phase II enzymes are known to be involved in the detoxification mechanism of xenobiotics and endogenous substances leading to cellular homeostasis (Noda et al. 2003). Ligand bound AHR/ARNT plays a key role in sex hormone signaling especially in estrogen dependent transactivation of estrogen receptor alpha (Matthews et al. 2005). Beyond the direct transcriptional regulation of genes by AHR/ARNT complex, AHR also interacts with other proteins that act as co–activators for target gene expression. Interaction of AHR with nuclear factor, erythroid 2 like 2 (NFE2L2) augments NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 (NQO1) gene expression, which in turn protects the cells from oxidative stress caused by cigarette smoke and other toxic ligands (Wang et al. 2013; Cheng et al. 2012). Activated AHR also associates with E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) that plays a crucial role in cell cycle transition. (Watabe et al. 2010). Consequently, the diverse role of AHR depends on the cell type and the stimuli that regulate the transcription of genes.

Conclusions

AHR signaling network is essential for understanding various biological processes mediated by AHR-regulated transcription of several genes. AHR is an emergent molecule that is involved in many diseases including cancer. Documentation of reactions pertaining to AHR signaling and development of pathway map based on the published literature will facilitate further research in AHR associated human diseases. The pathway data has been uploaded to NetPath database with the feasibility to download in various standard formats.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India for research support to the Institute of Bioinformatics, Bangalore. We thank the “Infosys Foundation” for research support to the Institute of Bioinformatics. We thank UK India Education and Research Initiative (UKIERI) for generous grant support. SDY is a recipient of DST-INSPIRE Senior Research Fellowship from Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. AR and JA are recipients of Senior Research Fellowship from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. RR is a recipient of Research Associateship from Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Abbreviations

- AHR

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- PTM

Post-translational modification

- HPRD

Human Protein Reference Database

- SBML

Systems Biology Markup Language

- PSI-MI

Proteomics Standards Initiative for Molecular Interaction

- BioPAX

Biological Pathway Exchange

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were declared.

Footnotes

Soujanya D. Yelamanchi; Hitendra Singh Solanki and Aneesha Radhakrishnan contributed equally

Contributor Information

Soujanya D. Yelamanchi, Email: soujanya@ibioinformatics.org

Hitendra Singh Solanki, Email: hitendra@ibioinformatics.org.

Aneesha Radhakrishnan, Email: aneesha@ibioinformatics.org.

Lavanya Balakrishnan, Email: lavanya.ibioinformatics@gmail.com.

Jayshree Advani, Email: jayshree@ibioinformatics.org.

Remya Raja, Email: remya@ibioinformatics.org.

Nandini A. Sahasrabuddhe, Email: nandini.jhmi@gmail.com

Premendu Prakash Mathur, Email: ppmathur@yahoo.com.

Pinaki Dutta, Email: pinaki_dutta@hotmail.com.

T. S. Keshava Prasad, Email: keshava@ibioinformatics.org.

Márta Korbonits, Email: m.korbonits@qmul.ac.uk.

Aditi Chatterjee, Phone: +91-080-28416140, Email: aditi@ibioinformatics.org.

Harsha Gowda, Phone: +91-080-28416140, Email: harsha@ibioinformatics.org.

Kanchan Kumar Mukherjee, Email: kk_mukherjee@hotmail.com.

References

- Abel J, Haarmann-Stemmann T. An introduction to the molecular basics of aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology. Biol Chem. 2010;391:1235–1248. doi: 10.1515/bc.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann B, Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Blatter MC, Estreicher A, Gasteiger E, Martin MJ, Michoud K, O’Donovan C, Phan I, Pilbout S, Schneider M. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Pociask DA, McAleer JP, Chan YR, Alcorn JF, Kreindler JL, Keyser MR, Shapiro SD, Houghton AM, Kolls JK, Zheng M. IL-17RA is required for CCL2 expression, macrophage recruitment, and emphysema in response to cigarette smoke. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YH, Huang SC, Lin CJ, Cheng LC, Li LA. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor protects lung adenocarcinoma cells against cigarette sidestream smoke particulates-induced oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;259:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E, Cary MP, Paley S, Fukuda K, Lemer C, Vastrik I, Wu G, D’Eustachio P, Schaefer C, Luciano J, Schacherer F, Martinez-Flores I, Hu Z, Jimenez-Jacinto V, Joshi-Tope G, Kandasamy K, Lopez-Fuentes AC, Mi H, Pichler E, Rodchenkov I, Splendiani A, Tkachev S, Zucker J, Gopinath G, Rajasimha H, Ramakrishnan R, Shah I, Syed M, Anwar N, Babur O, Blinov M, Brauner E, Corwin D, Donaldson S, Gibbons F, Goldberg R, Hornbeck P, Luna A, Murray-Rust P, Neumann E, Ruebenacker O, Samwald M, van Iersel M, Wimalaratne S, Allen K, Braun B, Whirl-Carrillo M, Cheung KH, Dahlquist K, Finney A, Gillespie M, Glass E, Gong L, Haw R, Honig M, Hubaut O, Kane D, Krupa S, Kutmon M, Leonard J, Marks D, Merberg D, Petri V, Pico A, Ravenscroft D, Ren L, Shah N, Sunshine M, Tang R, Whaley R, Letovksy S, Buetow KH, Rzhetsky A, Schachter V, Sobral BS, Dogrusoz U, McWeeney S, Aladjem M, Birney E, Collado-Vides J, Goto S, Hucka M, Le Novere N, Maltsev N, Pandey A, Thomas P, Wingender E, Karp PD, Sander C, Bader GD. The BioPAX community standard for pathway data sharing. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:935–942. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever DP, Opanashuk LA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor contributes to the proliferation of human medulloblastoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:669–678. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.077305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM, Barhoover MA, Kazmin D, McDonnell DP, Greenlee WF, Thomas RS. Activation of the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor inhibits invasive and metastatic features of human breast cancer cells and promotes breast cancer cell differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:359–369. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DA, Esakky P, Drury A, Lamb L, Moley KH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is important for proper seminiferous tubule architecture and sperm development in mice. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.108845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heliovaara E, Raitila A, Launonen V, Paetau A, Arola J, Lehtonen H, Sane T, Weil RJ, Vierimaa O, Salmela P, Tuppurainen K, Makinen M, Aaltonen LA, Karhu A. The expression of AIP-related molecules in elucidation of cellular pathways in pituitary adenomas. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2501–2507. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermjakob H, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Bader G, Wojcik J, Salwinski L, Ceol A, Moore S, Orchard S, Sarkans U, von Mering C, Roechert B, Poux S, Jung E, Mersch H, Kersey P, Lappe M, Li Y, Zeng R, Rana D, Nikolski M, Husi H, Brun C, Shanker K, Grant SG, Sander C, Bork P, Zhu W, Pandey A, Brazma A, Jacq B, Vidal M, Sherman D, Legrain P, Cesareni G, Xenarios I, Eisenberg D, Steipe B, Hogue C, Apweiler R. The HUPO PSI’s molecular interaction format--a community standard for the representation of protein interaction data. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nbt926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TH, Tsai CF, Hsu CY, Kuo PL, Lee JN, Chai CY, Wang SC, Tsai EM. Phthalates induce proliferation and invasiveness of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer through the AhR/HDAC6/c-Myc signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2012;26:778–787. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-191742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucka M, Finney A, Sauro HM, Bolouri H, Doyle JC, Kitano H, Arkin AP, Bornstein BJ, Bray D, Cornish-Bowden A, Cuellar AA, Dronov S, Gilles ED, Ginkel M, Gor V, Goryanin II, Hedley WJ, Hodgman TC, Hofmeyr JH, Hunter PJ, Juty NS, Kasberger JL, Kremling A, Kummer U, Le Novere N, Loew LM, Lucio D, Mendes P, Minch E, Mjolsness ED, Nakayama Y, Nelson MR, Nielsen PF, Sakurada T, Schaff JC, Shapiro BE, Shimizu TS, Spence HD, Stelling J, Takahashi K, Tomita M, Wagner J, Wang J. The systems biology markup language (SBML): a medium for representation and exchange of biochemical network models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:524–531. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrain-Rea ML, Angelini M, Gargano D, Tichomirowa MA, Daly AF, Vanbellinghen JF, D’Innocenzo E, Barlier A, Giangaspero F, Esposito V, Ventura L, Arcella A, Theodoropoulou M, Naves LA, Fajardo C, Zacharieva S, Rohmer V, Brue T, Gulino A, Cantore G, Alesse E, Beckers A. Expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and AHR-interacting protein in pituitary adenomas: pathological and clinical implications. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1029–1043. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadow S, Jux B, Zahner SP, Wingerath B, Chmill S, Clausen BE, Hengstler J, Esser C. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor is critical for homeostasis of invariant gammadelta T cells in the murine epidermis. J Immunol. 2011;187:3104–3110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Raju R, Keshava Prasad TS, Ramachandra YL, Mohan S, Pandey A. PathBuilder--open source software for annotating and developing pathway resources. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2860–2862. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy K, Mohan SS, Raju R, Keerthikumar S, Kumar GS, Venugopal AK, Telikicherla D, Navarro JD, Mathivanan S, Pecquet C, Gollapudi SK, Tattikota SG, Mohan S, Padhukasahasram H, Subbannayya Y, Goel R, Jacob HK, Zhong J, Sekhar R, Nanjappa V, Balakrishnan L, Subbaiah R, Ramachandra YL, Rahiman BA, Prasad TS, Lin JX, Houtman JC, Desiderio S, Renauld JC, Constantinescu SN, Ohara O, Hirano T, Kubo M, Singh S, Khatri P, Draghici S, Bader GD, Sander C, Leonard WJ, Pandey A. NetPath: a public resource of curated signal transduction pathways. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerley-Hamilton JS, Trask HW, Ridley CJ, Dufour E, Lesseur C, Ringelberg CS, Moodie KL, Shipman SL, Korc M, Gui J, Shworak NW, Tomlinson CR. Inherent and benzo[a]pyrene-induced differential aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling greatly affects life span, atherosclerosis, cardiac gene expression, and body and heart growth in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2012;126:391–404. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kewley RJ, Whitelaw ML, Chapman-Smith A. The mammalian basic helix-loop-helix/PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:189–204. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliopanos A, Kleeff J, Xiao Y, Safe S, Zimmermann A, Buchler MW, Friess H. Increased arylhydrocarbon receptor expression offers a potential therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:6059–6070. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees MJ, Peet DJ, Whitelaw ML. Defining the role for XAP2 in stabilization of the dioxin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35878–35888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey S, Papoutsakis ET. The evolving role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) in the normophysiology of hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:1223–1235. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9384-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglott D, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Tatusova T. Entrez Gene: gene-centered information at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D52–D57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconett CN, Sundar SN, Poindexter KM, Stueve TR, Bjeldanes LF, Firestone GL. Indole-3-carbinol triggers aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent estrogen receptor (ER)alpha protein degradation in breast cancer cells disrupting an ERalpha-GATA3 transcriptional cross-regulatory loop. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1166–1177. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martey CA, Baglole CJ, Gasiewicz TA, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a regulator of cigarette smoke induction of the cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin pathways in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Phys Lung Cell Mol Phys. 2005;289:L391–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00062.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J, Wihlen B, Thomsen J, Gustafsson JA. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription: ligand-dependent recruitment of estrogen receptor alpha to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-responsive promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5317–5328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5317-5328.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RM, Hernandez-Ramirez LC, Trivellin G, Zhou L, Roe SM, Korbonits M, Prodromou C. Structure of the TPR domain of AIP: lack of client protein interaction with the C-terminal alpha-7 helix of the TPR domain of AIP is sufficient for pituitary adenoma predisposition. PLoS One. 2012;7:e53339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray IA, Patterson AD, Perdew GH. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands in cancer: friend and foe. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:801–814. doi: 10.1038/nrc3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjappa V, Raju R, Muthusamy B, Sharma J, Thomas JK, Nidhina PAH, Harsha HC, Pandey A, Anilkumar G, Prasad TSK. A comprehensive curated reaction map of leptin signaling pathway. J Proteome Bioinf. 2011;4:184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LP, Bradfield CA. The search for endogenous activators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:102–116. doi: 10.1021/tx7001965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda S, Harada N, Hida A, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Gene expression of detoxifying enzymes in AhR and Nrf2 compound null mutant mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:105–111. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovrevik J, Lag M, Lecureur V, Gilot D, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Refsnes M, Schwarze PE, Skuland T, Becher R, Holme JA. AhR and Arnt differentially regulate NF-kappaB signaling and chemokine responses in human bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Commun Signals. 2014;12:48. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng TL, Chen J, Mao W, Liu X, Tao Y, Chen LZ, Chen MH. Potential therapeutic significance of increased expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in human gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1719–1729. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podechard N, Lecureur V, Le Ferrec E, Guenon I, Sparfel L, Gilot D, Gordon JR, Lagente V, Fardel O. Interleukin-8 induction by the environmental contaminant benzo(a)pyrene is aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent and leads to lung inflammation. Toxicol Lett. 2008;177:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad TSK, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A, Balakrishnan L, Marimuthu A, Banerjee S, Somanathan DS, Sebastian A, Rani S, Ray S, Harrys Kishore CJ, Kanth S, Ahmed M, Kashyap MK, Mohmood R, Ramachandra YL, Krishna V, Rahiman BA, Mohan S, Ranganathan P, Ramabadran S, Chaerkady R, Pandey A. Human protein reference database--2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D767–D772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan A, Raju R, Tuladhar N, Subbannayya T, Thomas JK, Goel R, Telikicherla D, Palapetta SM, Rahiman BA, Venkatesh DD, Urmila KK, Harsha HC, Mathur PP, Prasad TS, Pandey A, Shemanko C, Chatterjee A. A pathway map of prolactin signaling. J Cell Commun Signals. 2012;6:169–173. doi: 10.1007/s12079-012-0168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitila A, Lehtonen HJ, Arola J, Heliovaara E, Ahlsten M, Georgitsi M, Jalanko A, Paetau A, Aaltonen LA, Karhu A. Mice with inactivation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (Aip) display complete penetrance of pituitary adenomas with aberrant ARNT expression. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1969–1976. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss P, Petrulis JR, Hollingshead BD, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. Divergent roles of hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2 (XAP2) in human versus mouse ah receptor complexes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:700–709. doi: 10.1021/bi035827v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savouret JF, Berdeaux A, Casper RF. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its xenobiotic ligands: a fundamental trigger for cardiovascular diseases. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;13:104–113. doi: 10.1016/S0939-4753(03)80026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivellin G, Korbonits M. AIP and its interacting partners. J Endocrinol. 2011;210:137–155. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay JJ, Tchou-Wong KM, Greenberg AK, Pass H, Rom WN. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:1247–1256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji N, Fukuda K, Nagata Y, Okada H, Haga A, Hatakeyama S, Yoshida S, Okamoto T, Hosaka M, Sekine K, Ohtaka K, Yamamoto S, Otaka M, Grave E, Itoh H. The activation mechanism of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) by molecular chaperone HSP90. FEBS Open Bio. 2014;4:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Iersel MP, Kelder T, Pico AR, Hanspers K, Coort S, Conklin BR, Evelo C. Presenting and exploring biological pathways with PathVisio. BMC Bioinf. 2008;9:399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, Stockinger B. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature. 2008;453:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature06881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, He X, Szklarz GD, Bi Y, Rojanasakul Y, Ma Q. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 to mediate induction of NAD(P)H:quinoneoxidoreductase 1 by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;537:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe Y, Nazuka N, Tezuka M, Shimba S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor functions as a potent coactivator of E2F1-dependent trascription activity. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:389–397. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Li CY, Kong AN. Induction of phase I, II and III drug metabolism/transport by xenobiotics. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:249–268. doi: 10.1007/BF02977789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Qin C, Safe SH. Flavonoids as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: effects of structure and cell context. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1877–1882. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]