Dear Editor,

The survival of motor neurons (SMN) complex assembles the heptameric rings of Sm proteins (Sm core) on small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) to form small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs)1,2,3,4, the major components of the spliceosome5. The SMN complex consists of SMN, Unrip and Gemin2-86,7. SMN deficiency leads to correspondingly reduced snRNP assembly and is an underlying cause for spinal muscular atrophy, a common motor neuron degenerative disease8. The SMN complex functions to ensure Sm core assembly only on the correct snRNAs, therefore preventing aberrant Sm core formation. Such stringent specificity of the SMN complex toward snRNAs is conferred by Gemin5, which directly interacts with snRNA precursors (pre-snRNAs)9,10,11 and delivers them to sites of Sm core assembly and processing. Gemin5 recognizes the snRNP code comprised of the Sm site (AU5-6G) and an adjacent 3′-terminal stem loop via its N-terminal WD40 repeat domain (termed Gemin5-WD). Gemin5 also has been shown to bind the 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap12 and to downregulate internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation13. Although the function of Gemin5 in the biogenesis of snRNPs has been explored, the molecular mechanism for specific recognition of pre-snRNAs by Gemin5 remains elusive.

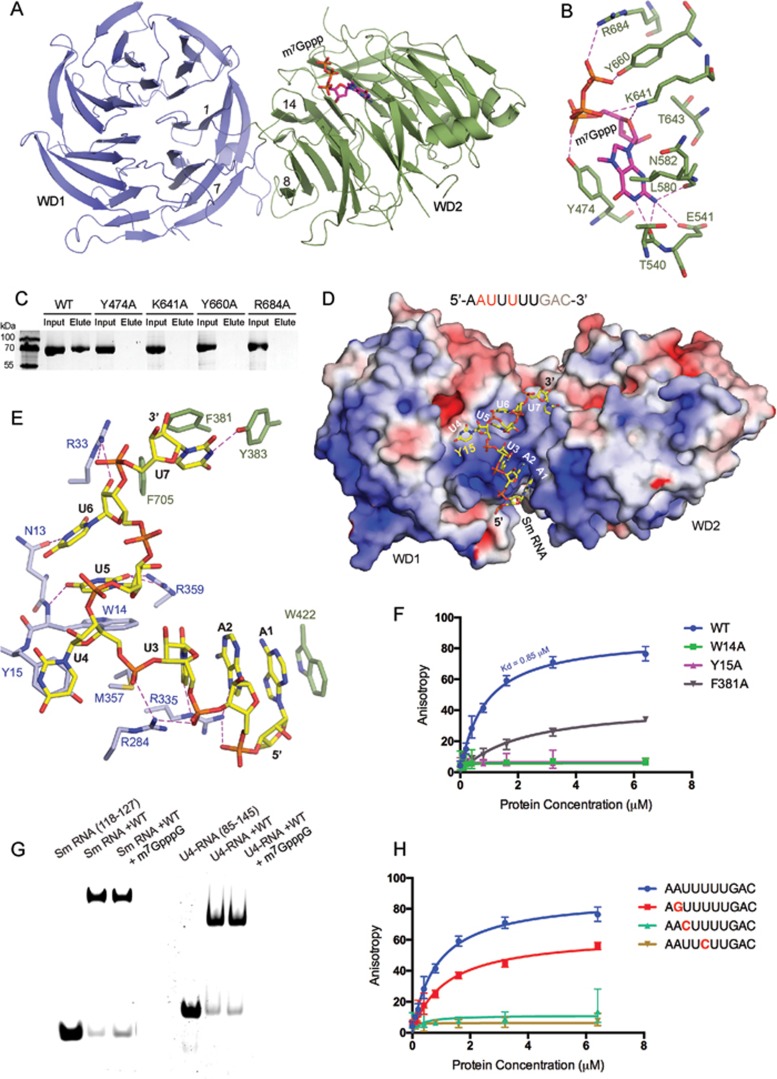

To reveal the molecular basis for specific recognition of pre-snRNAs by Gemin5, we determined the crystal structures of Gemin5-WD (aa 1-740) in its apo form and in complex with an m7GpppG cap analog and the Sm site RNA (5′-AAUUUUUGAC-3′ corresponding to nt 118-127 in pre-U4 snRNA) at resolutions of 3.0, 2.57 and 2.49 Å, respectively (Supplementary information, Table S1). Gemin5-WD contains 14 repeats of canonical WD40-motifs that fold into two connected seven-bladed β-propellers (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). The two doughnut-shaped propellers (WD1: blades 1-7, aa 19-377 and WD2: blades 8-14, aa 3-10 and 428-712) are similar in size, each ∼38 Å in diameter and ∼55 Å high, and twisted ∼15° askew relative to one another. The extreme N-terminal region of WD1 forms the outermost β-strand of blade 14 in WD2. Such a structural motif referred to as “molecular velcro” has been observed in the structures of Aip1 (Supplementary information, Figure S1A).

The structure of the Gemin5-WD/m7GpppG complex shows that the capped guanosine, m7G is inserted into the pocket at the top surface of WD2 (Figure 1A), whereas the other guanosine is not observed in the electron density map (Supplementary information, Figure S1B). Specifically, m7G is sandwiched between the aromatic ring of Tyr474 and the side chains of Leu580 and Asn582 (Figure 1B). In addition to the stacking interactions, the main chain carbonyl groups of Thr540 and Asn582, and the side chain carboxyl group of Glu541 are hydrogen bonded to the N1 and N2 atoms of m7G, respectively, whereas the side chains of Tyr474, Tyr660 and Arg684 form hydrogen bonds with the α- and γ-phosphate groups. Additional contacts involve the side chain of Lys641 and the ribose ring and the β-phosphate group. Consistent with the structure, mutations of invariant Tyr474, Lys641, Tyr660 and Arg684 (Supplementary information, Figure S1C) to Ala abolished the cap-binding activity of Gemin5, underscoring the importance of these residues in cap recognition (Figure 1C). The recognition of m7G by Gemin5 is specific as placing a trimethylated (Tri-mG) cap into the position occupied by the m7G cap would cause severe steric clashes with the neighboring residues (Supplementary information, Figure S1D). Gemin5-WD recognizes the m7G cap in a manner similar to those observed in the structures of CBC20, eIF4E, PARN and DcpS in complex with m7GpppG (Supplementary information, Figure S1E).

Figure 1.

Specific recognition of m7GpppG cap and the Sm site of pre-snRNA by Gemin5-WD. (A) Overall structure of Gemin5-WD in complex with m7GpppG cap. WD1 and WD2 of Gemin5-WD are shown in light blue and green, respectively. m7Gppp of the cap is shown in purple. (B) Interactions of the m7GpppG cap analog with Gemin5-WD. Residues involved in the interaction are shown as sticks and labeled. Hydrogen bonds are shown as pink dashed lines. (C) Cap-binding assays were performed with wild-type (WT) Gemin5-WD and its mutants. (D) Electrostatic surface potential of Gemin5-WD complexed with Sm RNA (−7.5–7.5 kT/e). Sm RNA (nt 118-127 in pre-U4) used in the study is shown with specificity-determining nucleotides in red and those not observed in the structure in grey. (E) Interactions of Sm RNA with Gemin5-WD. (F) Fluorescence anisotropy measurements of Sm RNA (nt 118-127) binding with Gemin5-WD and its variants. (G) RNA-binding assays of Gemin5-WD in the absence or the presence of 2.5-fold excess of m7GpppG. Sm RNA (nt 118-127) and longer U4-RNA (nt 85-145 in pre-U4) are used. (H) The specificity determinants of Sm RNA for Gemin5 recognition were examined by fluorescence anisotropy.

The structure of Gemin5-Sm RNA complex shows that the Sm site RNA binds to a positively charged concave surface formed between the two β-propellers WD1 and WD2 (Figure 1D). Gemin5-WD does not show significant conformational changes upon Sm RNA binding, as superposition of Gemin5-Sm RNA structure onto the apo-form gives a root mean-square deviation of 0.3 Å (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Out of the 10 nucleotides used for crystallization, only 7 nucleotides are observed in the electron density map (Supplementary information, Figure S1B). The bound Sm RNA displays an extended conformation with a U-shaped bend between U3 and U5, such that the uridine base of U4 flips out, pointing in the direction opposite to those of U3 and U5. The 5′ end of the Sm RNA contacts blade 8, and the 3′ end contacts blade 14 with majority of the interactions involving residues from WD1.

The Sm RNA is recognized specifically through two grooves formed on either side of Tyr15 in WD1 (Figure 1D). Tyr15 stacks against a flipped nucleotide U4 in the bound RNA. Toward the 5′ end of U4 is a shallow groove formed between blades 7 and 8 that holds nucleotides U3 and A2. The specificity of A2 and U3 is ensured by hydrogen-bonding interactions between their bases and the guanidinium group of Arg335 (Figure 1E). U3 and A2 stack against each other as well as against the first nucleobase, A1. Trp422 belonging to blade 8 of WD2 completes the interaction through stacking against A1. Toward the 3′ end of U4 is a pocket formed by residues Trp14, Arg359, Asn13 and Arg33, which holds the nucleobases U5 and U6. Trp14 stacks against U5, which in turn stacks against U6. Arg359 and the main chain amide group of Trp14 recognize the base of U5, whereas Asn13 recognizes the base of U6. The side chain of Arg33 is hydrogen-bonded to the ribose of U6 and the subsequent phosphate moiety. The terminal nucleobase of U7 stacks against Phe381 and is surrounded by hydrophobic residues Tyr383 and Phe705 (Figure 1E). In contrast to our structure showing the specific recognition of RNA, the WD40 domain of DDB2 recognizes dsDNA in a sequence-independent manner14 (Supplementary information, Figure S1F). These results confirm that WD40 domain is a versatile nucleic acid-binding module in addition to its role in protein-protein interactions.

To further characterize the role of residues involved in Sm RNA binding, we mutated several conserved residues (Supplementary information, Figure S1C) in Gemin5-WD and checked the mutational effects on RNA binding (Figure 1F). Of the mutants we generated, mutation of Trp14 or Tyr15 to Ala completely abolished the RNA-binding ability of Gemin5, whereas single Ala substitution of Phe381 dramatically reduced RNA binding, underscoring the essential role of these three residues in Sm RNA binding. As Sm RNA-binding and cap-binding sites on Gemin5-WD are in close proximity, we also investigated whether Sm RNA binding-defective mutants, W14A, Y15A and F381A can bind the cap analog. As expected, these mutants showed similar binding affinity to that of the wild-type protein (Supplementary information, Figure S1G). Furthermore, RNA-binding assays in the presence of 2.5-fold excess of m7GpppG showed that m7GpppG had no effect on Gemin5-WD's binding to RNA (Figure 1G). Taken together, these results suggest that Gemin5 recognizes the Sm site and the m7G cap of the pre-snRNA through two distinct binding sites.

Gemin5 has been shown to specifically recognize the 5′-AUUUUUG-3′ Sm site sequence of HSUR5 RNA of HVS with the first adenosine and the first and third uridines (corresponding to A2, U3 and U5 in Figure 1E) corresponding to the specificity determinants of pre-snRNA for Gemin5 recognition9. Moreover, pre-U1 snRNA containing a non-canonical Sm site 5′-AUUUGUG-3′ shows relatively weaker affinity to Gemin511. To verify the specificity determinants, we examined Gemin5-WD binding activities towards mutated Sm RNAs (Figure 1H). Substitution of A2 to G significantly decrease the RNA binding to Gemin5-WD, whereas the RNA binding was abolished when either U3 or U5 was substituted to C. Consistent with these findings, the specificity of A2 and U3 is ensured by the hydrogen bonds from the side chain of Arg335 to the purine and pyrimidine rings of A2 and U3, respectively. The specificity of U5 is provided by the hydrogen bonds between its base and Arg359. U6 corresponds to G5 in pre-U1 snRNA; substitution of U6 to G in the structure of Gemin5-Sm RNA would cause steric clashes with the main chain of Arg33 and side chain of Asn13.

Trp286 has been reported to be a key residue for the recognition of both m7G and the Sm site RNA11,12. However, Trp286 is located in a hydrophobic core of blade 6 of WD1, contacting Tyr15, which stacks against the flipped nucleotide U4 (Supplementary information, Figure S1H). Mutation of this residue is likely to destabilize the conformation of Tyr15, therefore affecting RNA binding. Trp286 is located far away from the cap-binding site. Therefore, it is unlikely to be involved in cap binding as suggested by Bradrick and Gromeier12. An alternative possibility is that mutation of Trp286 would disrupt the fold of Gemin5, thereby abolishing both cap and RNA binding of Gemin5. Consistent with this notion, we found that mutation of Trp286 to Ala led to the mutant protein being expressed in the inclusion bodies and insoluble.

In summary, we report structures of the WD40 domain of Gemin5 in complex with the m7G cap and the Sm site RNA. Gemin5 specifically recognizes the Sm RNA and the m7G cap through its first and second β-propellers, respectively. This dual recognition mechanism ensures the assembly of Sm core only on correct snRNAs, thereby preventing illicit Sm core formation. Our results provide a framework for further elucidating how Gemin5 delivers pre-snRNAs to the SMN complex for the biogenesis of snRNPs. The atomic coordinates and structure factors for apo Gemin5-WD, Gemin5-WD/m7GpppG and Gemin5-WD/Sm RNA complex structures have been deposited into Protein Data Bank under the accession code of 5H3S, 5H3T, 5H3U respectively.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the beamline scientists at the beamlines PX-I (SLS, PSI, Switzerland), ID-23-1 (ESRF, Grenoble, France) and BL13B1 (NSRRC, Taiwan, China) for assistance of X-ray data collection. This work was supported by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Data collection and refinement statistics

Gemin5-WD and actin interacting protein 1 (Aip1) share similar topology.

References

- Pellizzoni L, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. Science 2002; 298:1775–1779. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meister G, Buhler D, Pillai R, et al. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3:945–949. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kroiss M, Schultz J, Wiesner J, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:10045–10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grimm C, Chari A, Pelz JP, et al. Mol Cell 2013; 49:692–703. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Will CL, Luhrmann R. Spliceosomal UsnRNP biogenesis, structure and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2001; 13:290–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle DJ, Kasim M, Yong J, et al. The SMN complex: an assembly machine for RNPs. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2006; 71:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carissimi C, Baccon J, Straccia M, et al. FEBS Lett 2005; 579:2348–2354. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rossoll W, Bassell GJ. Results Probl Cell Differ 2009; 48:289–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Battle DJ, Lau CK, Wan L, et al. Mol Cell 2006; 23:273–279. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yong J, Kasim M, Bachorik JL, et al. Mol Cell 2010; 38:551–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lau CK, Bachorik JL, Dreyfuss G. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16:486–491. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bradrick SS, Gromeier M. PLoS One 2009; 4:e7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pineiro D, Fernandez N, Ramajo J, et al. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41:1017–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Scrima A, Konickova R, Czyzewski BK, et al. Cell 2008; 135:1213–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data collection and refinement statistics

Gemin5-WD and actin interacting protein 1 (Aip1) share similar topology.