Abstract

Background

Open esophagectomy (OE) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy (MIO) reduces complications in resectable esophageal cancer. The aim of this study is to explore the superiority of MIO in reducing complications and in-hospital mortality than OE.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, Science Citation Index, Wanfang, and Wiley Online Library were thoroughly searched. Odds ratio (OR)/weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to assess the strength of association.

Results

Fifty-seven studies containing 15,790 cases of resectable esophageal cancer were included. MIO had less intraoperative blood loss, short hospital stay, and high operative time (P < 0.05) than OE. MIO also had reduced incidence of total complications; (OR = 0.700, 95% CI = 0.626 ~ 0.781, P V < 0.05), pulmonary complications (OR = 0.527, 95% CI = 0431 ~ 0.645, P V < 0.05), cardiovascular complications (OR = 0.770, 95% CI = 0.681 ~ 0.872, P V < 0.05), and surgical technology related (STR) complications (OR = 0.639, 95% CI = 0.522 ~ 0.781, P V < 0.05), as well as lower in-hospital mortality (OR = 0.668, 95% CI = 0.539 ~ 0.827, P V < 0.05). However, the number of harvested lymph nodes, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, gastrointestinal complications, anastomotic leak (AL), and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (RLNP) had no significant difference.

Conclusions

MIO is superior to OE in terms of perioperative complications and in-hospital mortality.

Keywords: Minimally invasive esophagectomy, Open esophagectomy, Complications, Mortality

Background

A global incidence of esophageal cancer has increased by 50% in the past two decades. Each year, around 482,300 people are diagnosed with esophageal cancer, and 84.3% die of the disease worldwide [1, 2]. At present, the primary method of treating patients with esophageal cancer has been surgery. However, the traditional open esophagectomy (OE) procedure has high complication rates resulting in significant morbidity and mortality [3, 4]. Various studies showed in-hospital mortality between 1.2 and 8.8% [4–7], even as high as 29% [8].

Minimally invasive oesophagectomy (MIO), which was first described in the 1990s [9, 10], was attributed to be superior in reducing postoperative outcomes, without compromising oncological outcomes and avoiding thoracotomy and laparotomy. The basis of minimally invasive techniques in esophageal surgery is to maintain the therapy effectiveness and quality of traditional operations, while reducing perioperative injury. Nevertheless, the real benefits of minimally invasive approach for esophagectomy are still controversial [11–13]. A number of meta-analyses and even randomized controlled trials demonstrated MIO to be superior in reducing risk of postoperative outcomes, but their results are not very consistent, especially on the issue of in-hospital mortality [14–30]. Furthermore, these studies ignored preoperative clinical data and other Chinese relevant literatures. We, therefore, performed a meta-analysis combining the relevant publications and comprehensively assess the superiority of MIO.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

MEDLINE, Embase, Science Citation Index, Wanfang, and Wiley Online Library were thoroughly searched with terms “Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy” or “Open Esophagectomy,” “Esophagectomy,””MIE,” “laparasc,” “thoracosc,” “VATS,” “transhiatal” (date until May 2016). Relevant literatures containing full text were back tracked thoroughly, while abstracts and unpublished reports were excluded.

Selections of studies

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) randomized or non-randomized controlled studies with parallel controls, (2) comparison on OE versus MIO, (3) sufficient data of estimated odds ratios (ORs)/weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) studies that were not compared or case report, (2) incomplete literature, and (3) overlapped studies.

Data extraction

Two investigators read all the included literatures carefully and extracted all the data, such as first author, published year, numbers of case and controls, outcomes of interest, etc. If two investigators have divergent ideas on any data, the third investigator would be asked to check and reach consensus on the data.

Outcomes of interest

Definition of MIO was thoracoscopic/laparotomy-assisted esophagectomy, hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy, total thoracoscopic/hand-assisted thoracotomy, hand-assisted laparotomy, or minilaparotomy/laparoscopic esophagectomy.

Preoperative clinical data included age, neoadjuvant therapy, comorbidity, TNM staging, and gender.

Postoperative data contained operative duration, blood loss, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, hospital stay, and harvested lymph nodes.

The complications are as follows. (1) Mortality included in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality. (2) Pulmonary complications included pneumonia, respiratory failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), etc. (3) Cardiovascular complications included arrhythmia, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, etc. (4) Gastrointestinal complications included gastric tip necrosis, anastomotic stricture, delayed gastric emptying, gastric volvulus, etc. (5) Surgical technology related (STR) complications included splenic laceration, tracheal laceration, pneumothorax, chylothorax, hemorrhage, etc.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using STATA 11 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, 2011). Fixed or random effects models [31] were used. Odds ratio (OR) was used for categorical variables, while weighted mean difference (WMD) was used for continuous variables, such as operative time, harvested lymph nodes, and blood loss [32]. Q test was used to check the heterogeneity among each study. If the heterogeneity was high (I 2 > 50%), Random Effects Model was used to calculate the pooled OR/WMD. Otherwise, the fixed effects model was used [33]. If the heterogeneity test was statistically significant, sensitivity analysis, subgroup analysis, and Galbraith Plot Analysis were performed to find out potential origin of heterogeneity. Egger’s Test and Begg’s Funnel Plot were used for diagnosis of potential publication bias [34]. A P value <0.05 was considered as statistical significance. Duval and Tweedie nonparametric “trim and fill” procedure was used to assess the possible effect of publication bias [35].

The Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the validity and quality of studies [36], as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook [37]. This scale assigns a star rating based on pre-specified criteria. A total number of quality star ranged from one (low quality) to nine (high quality). A maximum of one star can be attained for each category, except comparability, which has maximum of two stars. The more the stars, the higher is the quality of study.

Results

Study characteristics

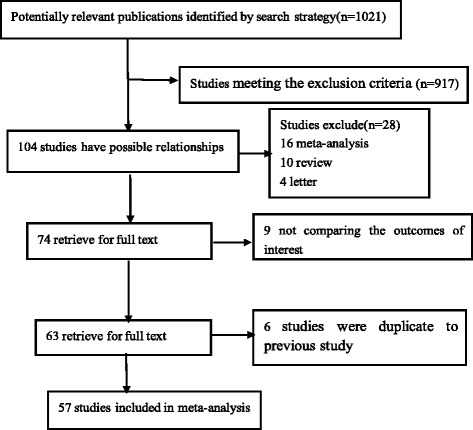

A flow chart of the literature search process is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 1021 unique records were identified by search strategy; 917 records were excluded; 16 studies were meta-analyses or systematic overviews [14–19]; ten were review; and four were letter; nine studies did not compare the outcomes of interest [3, 5–12], and six studies were duplicate to previous study. Therefore, 57 studies containing 15,790 cases (both MIO and OE) were included in this meta-analysis [30, 38–93].

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart explaining the selection of 57 studies included in the meta-analysis

Preoperative clinical data as well as quality star ranging from 6 to 8 are shown in Table 1. Of 15,790 cases, 5235 (33.2%) were MIO and 10,555 (66.8%) were OE. Thirty one studies were done in European countries and 26 in Asian countries, where 13 were from China [45–57]. Moreover, 39 studies involved total MIE, 12 studies thoracoscopic-assisted MIE (TA), and seven studies were hybrid (TA + MIE). TNM staging were reported in 40 studies (6265 cases), where 1973 patients (64.4%) in the MIO group and 1042 patients (32.5%) in the OE group were of early stage (stages I and II), mainly male (78.4% (MIO) vs 68.3% (OE)).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in this meta-analysis

| Study | Year | Country | Cases | Gender (M) | Age, years | NT | NOS | Hybrid | Preoperative comorbidity (MIO/OE) | TNM stage (MIO/OE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MIO/OE) | (MIO/OE) | (MIO/OE) | (MIO/OE) | Cardiovascular | Pulmonary | Diabetes | 0 + I + II | III + IV | |||||

| Nguyen | 2000 | USA | 18/36 | 7/29 | 64 ± 12/67 ± 8 | 9/9 | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Osugi | 2003 | Japan | 77/72 | 64/57 | 63.7 ± 9 · 6/64 · ±9 · 3 | NR | 7 | TA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kunisaki | 2004 | Japan | 15/30 | 12/21 | 62.3 ± 8.1/63 ± 6 | NR | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bernabe | 2004 | USA | 17/14 | 16/11 | 63.9 ± 13.5/64.1 ± 10.7 | NR | 6 | TA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Van den Broek | 2004 | Netherlands | 25/20 | 19/14 | 63 ± 8/64 ± 8 | 17/4 | 7 | TA | NR | NR | NR | 8/10 | 17/10 |

| Braghetto | 2006 | Chile | 47/119 | NR | NR | 0/0 | 8 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 41/80 | 6/39 |

| Bresadola | 2006 | Italy | 14/14 | 8/13 | 61.9 ± 7.7/59.3 ± 10.9 | NR | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 11/6 | 3/8 |

| Shiraishi | 2006 | Japan | 116/37 | 94/31 | 61.5 ± 8.1/66.5 ± 9.3 | 26/10 | 7 | Hybrid | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Smithers | 2007 | Australia | 332/114 | 267/104 | 64 (27–85)/62.5 (29–81) | 136/29 | 8 | Hybrid | 76/22 | NR | 27/4 | 192/36 | 118/75 |

| Benzoni | 2007 | Italy | 9/13 | 6/11 | 63.6 ± 2.6/60.2 ± 2.4 | 6/6 | 8 | TA | NR | 2/4 | NR | 9/7 | 0/6 |

| Fabian | 2008 | USA | 22/43 | 16/31 | 63 (46–86)/61 (35–82) | 9/16 | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 14/25 | 7/19 |

| Parameswaran | 2009 | UK | 50/30 | 45/21 | 67 (47–81)/68 (47–81) | 32/12 | 8 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 27/17 | 23/13 |

| Saha | 2009 | UK | 16/28 | 13/24 | 65 (50–80)/64 (35–78) | NR | 8 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Zingg | 2009 | Australia | 56/98 | 45/71 | 66.3 ± 1.3/67.8 ± 1.1 | 40/48 | 8 | MIE | 4/7 | 13/35 | 6/12 | 35/47 | 21/42 |

| Pham | 2010 | USA | 44/46 | 41/33 | 63 ± 8.6/61 ± 10.7 | 29/23 | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 20/20 | 20/19 |

| Perry | 2010 | USA | 21/21 | 18/17 | 69 ± 8/61 ± 9 | NR | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hamouda | 2010 | UK | 51/24 | 44/23 | 62/60 | 44/20 | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Safranek | 2010 | UK | 75/46 | 53/38 | 60 (44–77)/64(41–74) | 71/34 | 7 | Hybrid | NR | NR | NR | 31/29 | 44/17 |

| Schoppmann | 2010 | Australia | 31/31 | 25/21 | 61.5 (36–75)/58.6 (34–77) | 15/7 | 8 | MIE | 6/8 | 10/8 | 1/1 | 18/19 | 13/12 |

| Schröder | 2010 | Germany | 238/181 | 198/151 | 61.1 (60–62)/57.8 (56–59) | 144/66 | 6 | TA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mehran | 2011 | USA | 44/44 | 43/40 | 61.0 (42–79)/62.5 (38–83) | 31/30 | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 23/21 | 16/20 |

| Berger | 2011 | USA | 65/53 | 51/38 | 61 (41–78)/62 (40–86) | 28/43 | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 52/41 | 13/12 |

| Lee | 2011 | Japan | 74/64 | 73/61 | 59.7 ± 10.3/56.6 ± 11.6 | 47/52 | 8 | Hybrid | NR | NR | NR | 54/49 | 20/15 |

| Nafteux | 2011 | Belgium | 65/101 | 52/81 | 63 (41–82)/64 (29–82) | NR | 8 | MIE | 11/24 | 6/13 | 6/12 | NR | NR |

| Yamasaki | 2011 | Japan | 109/107 | 87/95 | 64.6 ± 8.5/64.7 ± 8.0 | 85/68 | 8 | TA | 20/20 | 11/13 | 10/6 | NR | NR |

| Biere | 2012 | Netherlands | 59/56 | 43/46 | 62 (34–75)/62 (42–75) | 59/56 | 8 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 31/26 | 15/19 |

| Maas | 2012 | Netherlands | 50/50 | 41/33 | 62.5 (57–69)/65 (57–69) | 23/13 | 8 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 19/19 | 31/31 |

| Briez | 2012 | France | 140/140 | 110/117 | NR | 67/69 | 8 | TA | NR | NR | NR | 92/89 | 48/51 |

| Kinjo | 2012 | Japan | 106/79 | 87/70 | 62.7 ± 7.4/63.3 ± 8.6 | 54/11 | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 65/45 | 41/34 |

| Mamidanna | 2012 | UK | 1155/6347 | 892/4870 | NR | NR | 7 | MIE | 400/2234 | 141/782 | 90/598 | NR | NR |

| Sihag | 2012 | USA | 38/76 | 29/61 | 61.4 ± 8.1/63.3 ± 9.3 | 25/46 | 7 | MIE | 6/16 | 8/13 | NR | 29/53 | 9/23 |

| Sundaram | 2012 | USA | 47/57 | 38/52 | 67.3 (42–79)/61.7 (34–84) | 35/40 | 8 | MIE | 33/42 | NR | 11/14 | NR | NR |

| Tsujimoto | 2012 | Japan | 22/27 | 21/21 | 70 ± 5.4/67 ± 10.1 | 8/16 | 6 | TA | NR | NR | NR | 12/14 | 10/13 |

| Javidfar | 2012 | USA | 92/165 | 71/122 | 65 (56–74)/68 (60–74) | 51/96 | 7 | MIE | 9/23 | 9/23 | 22/35 | 65/96 | 27/69 |

| Bailey | 2013 | UK | 39/31 | 32/27 | 65 (37–78)/62 (38–78) | 33/31 | 7 | TA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ichikawa | 2013 | Japan | 152/163 | 129/145 | 63.8 ± 8.5/64.6 ± 8.6 | 54/64 | 8 | TA | 23/35 | 21/24 | 26/37 | 101/81 | 51/79 |

| Kitagawa | 2013 | Japan | 45/47 | 35/40 | 63 (47–77)/64 (39–83) | 8/11 | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | 8/8 | NR | NR |

| Noble | 2013 | UK | 53/53 | 43/45 | 66 (45–85)/64 (36–81) | 13/11 | 8 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Parameswaran | 2013 | UK | 67/19 | 47/15 | 64 (45–84)/64 (51–77) | 50/17 | 7 | Hybrid | NR | NR | NR | 43/8 | 23/11 |

| Takeno | 2013 | Japan | 91/166 | 77/147 | 63.7/64.2 | NR | 8 | TA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kubo | 2014 | Japan | 135/74 | 111/60 | 64.1 ± 8.2/62.2 ± 7.2 | 22/4 | 7 | Hybrid | 12/3 | 9/7 | NR | 112/41 | 23/33 |

| Schneider | 2014 | UK | 19/61 | 46/15 | 62.3 (35–74)/66.7 (45–79) | 7/45 | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 16/36 | 2/24 |

| Daiko | 2015 | Japan | 31/33 | 28/28 | 66 (49–78)/65 (49–76) | NR | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 23/32 | 8/1 |

| Kauppi | 2015 | Finland | 74/79 | 59/68 | 66 (51–85)/63 (39–82) | 61/62 | 8 | MIE | 14/17 | 12/14 | 17/13 | 28/25 | 46/54 |

| Law | 1997 | China | 18/63 | 13/55 | 66 (43–80)/63 (36–84) | NR | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 5/15 | 13/45 |

| Chen | 2010 | China | 67/38 | 45/25 | 61 ± 7/66 ± 6 | NR | 7 | MIE | 15/4 | 10/3 | 9/2 | 42/15 | 25/23 |

| Gao | 2011 | China | 96/78 | 89/70 | 58.5 ± 7.3/59.1 ± 6.4 | NR | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 54/40 | 42/38 |

| Shen | 2012 | China | 76/71 | 52/50 | 60.9 ± 9/62.6 ± 8.7 | NR | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 41/44 | 35/27 |

| Liu | 2012 | China | 98/105 | 67/71 | 62.3 ± 10.1/65.8 ± 7.6 | NR | 6 | MIE | 13/18 | 40/37 | 6/8 | 51/43 | 47/62 |

| Mao | 2012 | China | 34/38 | 28/26 | 62/60 | NR | 6 | TA | NR | NR | NR | 27/21 | 7/17 |

| Wang | 2012 | China | 260/322 | 194/232 | 61.6 ± 8.761.2 ± 8.8 | 37/44 | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 201/234 | 59/88 |

| MU | 2014 | China | 176/142 | 116/106 | 60 (55–66)/59 (54–62) | NR | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 120/109 | 56/33 |

| Meng | 2014 | China | 94/89 | 65/63 | 59.7 ± 9.3/61.1 ± 6.7 | NR | 7 | MIE | 11/14 | 27/31 | 12/10 | 56/50 | 38/39 |

| Zhang | 2014 | China | 60/61 | 48/47 | 62.4 ± 8/61.8 ± 8.4 | NR | 6 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 41/42 | 19/19 |

| Chen | 2015 | China | 59/59 | 42/40 | 57 (41–72)/56 (48–71) | NR | 7 | MIE | 4/2 | 1/0 | 2/3 | 56/55 | 3/4 |

| Yang | 2015 | China | 62/62 | 45/45 | 62 ± 9/62 ± 8 | NR | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 44/43 | 18/19 |

| Li | 2015 | China | 89/318 | 66/227 | 73 (70–83)/73 (70–85) | NR | 7 | MIE | NR | NR | NR | 64/188 | 25/126 |

NT neoadjuvant therapy, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale, MIO minimally invasive oesophagectomy, including MIE,TA, and hybrid MIE, OE open esophagectomy, MIE total minimally invasive esophagectomy, TA thoracoscopic-assisted MIE, Hybrid hybrid minimally invasive oesophagectomy

Preoperative clinical data

Fifty-seven studies reported patient’s age. There was no statistical significance between two groups after pooled analysis (WMD = −0.343, 95%CI = −1.200 ~ 0.514, P V < 0.433). Thirty-three studies (5243 cases) reported that the patients in MIE group received more neoadjuvant therapy (Table 3, pooled OR = 1.364, 95% CI = 1.042 ~ 1.785, P V = 0.024). Sixteen studies reported preoperative comorbidity, where there was no statistical significance between two groups (P V > 0.05).

Table 3.

Differences between MIO and OE surgery patients

| Variables | No. studies | WMD/OR (95%CI) | P V | P Q | I 2 (%) | P E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57 (n = 15790) | −0.343 (−1.200, 0.514) | 0.433 | <0.05 | 68.1 | 0.059 |

| NT | 34 (n = 5138) | 1.364 (1.042,1.785) | 0.024 | <0.05 | 73.0 | 0.362 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 16 (n = 10337) | 0.913 (0.815,1.022) | 0.112 | 0.030 | 44.2 | 0.930 |

| Pulmonary | 15 (n = 9779) | 0.949 (0.819,1.099) | 0.485 | 0.881 | 0 | 0.722 |

| Diabetes | 15 (n = 9983) | 0.942 (0.798,1.111) | 0.476 | 0.457 | 0 | 0.082 |

| Operating time, min | 46 (n = 6260) | 24.427 (10.912,37.943) | <0.05 | <0.05 | 96.1 | 0.155 |

| Blood loss, ml | 40 (n = 5285) | −196.060 (−255.195,-136.926) | <0.05 | <0.05 | 98.9 | 0.592 |

| LN harvest | 46 (n = 6390) | −1.275 (−5.851,3.301) | 0.585 | <0.05 | 99.8 | 0.786 |

| LOS, day | 45 (n = 13899) | −3.660 (−4.891,-2.428) | <0.05 | <0.05 | 86.0 | 0.175 |

| ICU stay, day | 27 (n = 10761) | −1.599 (−2.680, −0.518) | 0.004 | <0.05 | 98.2 | 0.078 |

| Complication | ||||||

| Total complication | 35 (n = 5991) | 0.700 (0.626,0.781) | <0.05 | 0.012 | 38.5 | 0.178 |

| Pulmonary | 50 (n = 14781) | 0.527 (0.431, 0.645) | <0.05 | <0.05 | 60.3 | <0.05 |

| Circulatory system | 36 (n = 12883) | 0.770 (0.681,0.872) | <0.05 | 0.427 | 2.4 | 0.386 |

| Digestive system | 21 (n = 4081) | 1.097 (0.835,1.442) | 0.507 | 0.083 | 31.7 | 0.664 |

| AL | 50 (n = 7528) | 1.023 (0.870,1.202) | 0.785 | 0.304 | 8.5 | 0.018 |

| RLNP | 37 (n = 5429) | 1.108 (0.917,1.339) | 0.289 | 0.089 | 24.8 | 0.014 |

| STR | 39 (n = 5991) | 0.639 (0.522,0.781) | <0.05 | 0.918 | 0 | 0.206 |

| Mortality | 38 (n = 14132) | 0.668 (0.539,0.827) | <0.05 | 0.944 | 0 | 0.508 |

NT neoadjuvant therapy, LN lymph node, LOS length of hospital stay, ICU intensive care unit, AL anastomotic leak, RLNP recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, STR surgical technology-related, Mortality in-hospital/30-day mortality, P V the P value for pooled, P Q the P value for Q test, P E the P value for Egger’s test

Postoperative data

Forty-six studies (6260 cases) reported that operative time was higher in MIO group (Table 3, pooled WMD = 1.364, 95% CI = 10.912 ~ 37.943, P V < 0.05). Forty studies (5285 cases) reported less blood loss in MIO group (WMD = −196, 95% CI = −255.195 ~ −136.926, P V < 0.05). Duration of hospital stay (13,899 cases), including ICU stay (10,761 cases), were found to be significantly lower in MIO group (WMD = −1.599, 95% CI = (−2.680 ~ −0.518,P V < 0.05 and WMD = −3.66, 95% CI = −4.891 ~ −2.428, P V < 0.05). There was no significant difference between two groups in forty-six studies (6390 cases) reported for harvested lymph nodes (Table 3, WMD = −1.275, 95% CI = −5.851 ~ 3.301, P V = 0.585). There was significant heterogeneity in the outcome among all the indices of postoperative data. Stratified analysis was performed according to ethnicity (Asian/Caucasian); however, heterogeneity still existed in subgroups. We then gradually removed small sample size, with emphasis on not altering the overall qualitative results.

Complications

MIO and total complications

Thirty-five studies including 5991 cases reported total complications, where 41.5% (1206/2907) were allocated to MIE group and 48.2% (1486/3084) were allocated to OE group, with overall morbidity of 44.9% (2692/5991) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes of complication in included studies

| Study | Total | Pulmonary | Circulatory system | Digestive system | AL | RLNP | STR | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE | MIO/OE |

| Nguyen | NR | 2/6 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 3/4 | 0/4 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| Osugi | 25/27 | 12/14 | 3/2 | NR | 2/1 | 11/9 | 4/4 | NR |

| Kunisaki | NR | 0/1 | NR | NR | 2/1 | 3/3 | NR | NR |

| Bernabe | NR | NR | NR | 7/8 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Van den Broek | 14/18 | 2/2 | NR | 3/5 | 2/3 | 2/3 | 2/4 | NR |

| Braghetto | 18/72 | 7/22 | 0/3 | 4/6 | 3/17 | 0/2 | 1/0 | 3/13 |

| Bresadola | NR | 1/2 | 1/0 | NR | 1/2 | 3/1 | NR | NR |

| Shiraishi | NR | 25/12 | 13/9 | NR | 12/9 | 42/10 | NR | 6/5 |

| Smithers | 207/76 | 106/44 | 60/24 | 83/9 | 17/11 | 8/0 | 25/14 | 7/3 |

| Benzoni | NR | 0/2 | NR | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | NR | 0/1 |

| Fabian | 15/31 | 1/18 | 5/8 | 1/0 | 3/3 | 1/2 | 0/3 | 1/4 |

| Parameswaran | 24/15 | 4/2 | 0/3 | 3/1 | 4/1 | 6/0 | 5/4 | NR |

| Saha | 3/6 | NR | NR | NR | 2/3 | NR | NR | 0/2 |

| Zingg | 19/20 | 17/33 | NR | NR | 11/11 | NR | 2/2 | 2/6 |

| Pham | 34/27 | 13/9 | 18/16 | 3/1 | 4/5 | 6/0 | 3/10 | 3/2 |

| Perry | 13/17 | 2/3 | 5/8 | 5/4 | 4/6 | 1/2 | 2/5 | NR |

| Hamouda | NR | 15/5 | 5/3 | 3/1 | 4/2 | NR | 3/0 | NR |

| Safranek | NR | 19/13 | NR | 17/4 | 11/1 | 10/1 | 5/5 | 3/1 |

| Schoppmann | NR | 5/17 | NR | 0/1 | 1/8 | 4/13 | 3/4 | NR |

| Schröder | NR | NR | NR | NR | 18/17 | NR | NR | 7/11 |

| Mehran | NR | 14/15 | 9/9 | 18/8 | 11/6 | NR | NR | NR |

| Berger | 31/32 | 10/22 | 1/6 | NR | 9/6 | NR | NR | 5/4 |

| Lee | NR | 11/20 | NR | NR | 10/18 | NR | NR | 4/8 |

| Nafteux | 44/61 | 17/47 | 11/13 | 13/6 | 5/10 | NR | 6/9 | 2/2 |

| Yamasaki | 26/38 | 7/15 | 3/6 | 0/2 | 6/4 | 17/20 | 3/5 | 0/2 |

| Biere | NR | 14/35 | 1/1 | 1/0 | 7/4 | 1/8 | 1/1 | 3/1 |

| Maas | 21/33 | 9/13 | 3/6 | NR | 4/3 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 0/1 |

| Briez | 50/83 | 22/60 | NR | 6/4 | 8/6 | NR | NR | 2/10 |

| Kinjo | 54/54 | 22/31 | 10/5 | 8/9 | 11/13 | 21/10 | 4/10 | NR |

| Mamidanna | NR | 276/1419 | 165/1035 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 46/274 |

| Sihag | NR | 1/33 | 5/19 | NR | 0/2 | NR | 3/5 | 0/2 |

| Sundaram | 28/41 | 5/19 | 9/19 | 26/10 | 4/4 | 1/1 | 10/11 | 2/1 |

| Tsujimoto | 13/16 | 2/10 | NR | 1/1 | 7/3 | 2/2 | 1/4 | 1/5 |

| Javidfar | NR | 9/26 | 29/56 | 19/33 | 5/7 | 3/0 | 22/38 | 3/7 |

| Bailey | NR | 15/18 | 4/9 | 1/0 | 1/0 | NR | 6/15 | 2/2 |

| Ichikawa | 94/117 | 20/33 | 17/38 | 4/5 | 14/27 | 60/77 | 2/2 | 0/8 |

| Kitagawa | NR | 6/14 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 13/20 | 2/1 |

| Noble | NR | 14/18 | 10/7 | NR | 5/2 | NR | 2/2 | 1/1 |

| Parameswaran | 42/12 | 7/2 | 2/1 | 14/2 | NR | 2/1 | 6/3 | 3/1 |

| Takeno | 39/69 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4/15 |

| Kubo | 57/35 | 13/16 | NR | 2/0 | 10/7 | 37/14 | 18/19 | 2/2 |

| Schneider | 7/13 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0/2 |

| Daiko | 10/12 | NR | NR | NR | 6/4 | 3/6 | 2/6 | NR |

| Kauppi | 37/48 | 13/15 | 17/27 | 5/14 | 5/5 | 0/4 | 12/11 | NR |

| Law | NR | 4/15 | 3/16 | NR | 0/2 | 4/8 | NR | NR |

| Chen | NR | 7/10 | NR | 2/0 | 1/0 | NR | 2/1 | NR |

| Gao | 31/36 | 13/11 | NR | 7/12 | 7/6 | 2/4 | 1/2 | 2/3 |

| Shen | 32/28 | 5/6 | 9/8 | 1/1 | 16/14 | 7/2 | 2/3 | 0/1 |

| Liu | 22/38 | 5/21 | 4/13 | 3/5 | 2/4 | 3/4 | 3/5 | 1/3 |

| Mao | 14/16 | 0/2 | 1/6 | 0/1 | 8/1 | 5/3 | NR | NR |

| Wang | 90/145 | 12/23 | 21/36 | 11/13 | 26/32 | 6/7 | 8/16 | 2/11 |

| MU | 28/22 | 6/4 | NR | NR | 12/4 | NR | NR | 1/1 |

| Meng | 24/41 | 9/24 | 4/11 | 2/2 | 6/7 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 1/4 |

| Zhang | NR | 4/7 | 3/5 | 3/2 | 3/2 | 2/1 | 2/7 | NR |

| Chen | 14/19 | 2/4 | 3/5 | NR | 2/3 | 4/5 | 1/1 | NR |

| Yang | 19/31 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Li | 32/137 | 8/51 | 9/34 | 2/5 | 19/45 | 18/49 | 4/19 | 3/16 |

AL anastomotic leak, RLNP recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, STR surgical technology-related, Mortality in-hospital/30-day mortality

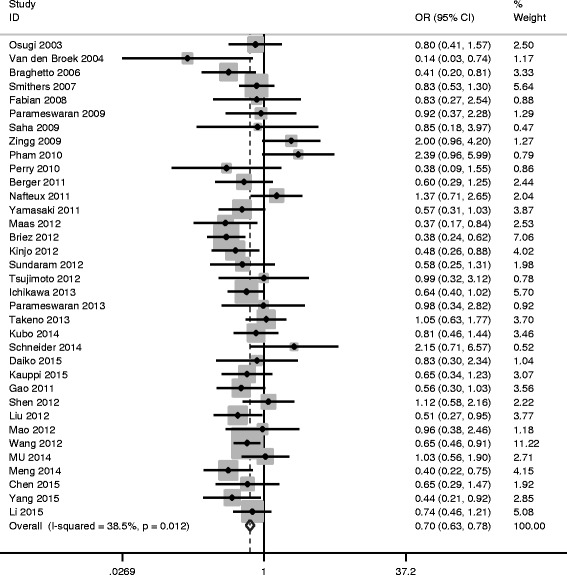

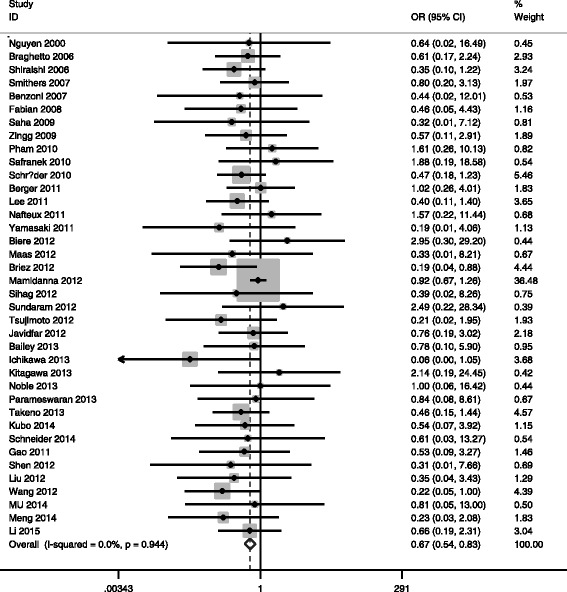

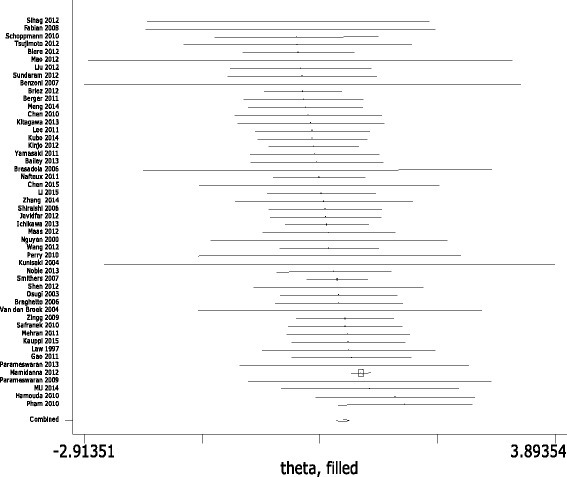

Low heterogeneity was found among studies (I 2 = 38.5%, P Q = 0.012), so the fixed effects model was used (see Table 3). The pooled OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.626 ~ 0.781, P V < 0.05 indicated total complication was significantly lower in MIO group (Fig. 2). Publication bias was assessed by Egger’s Test and Begg’s Funnel Plot; no publication bias could be discovered (P E = 0.178).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis for MIE and total complications

MIO and pulmonary complications

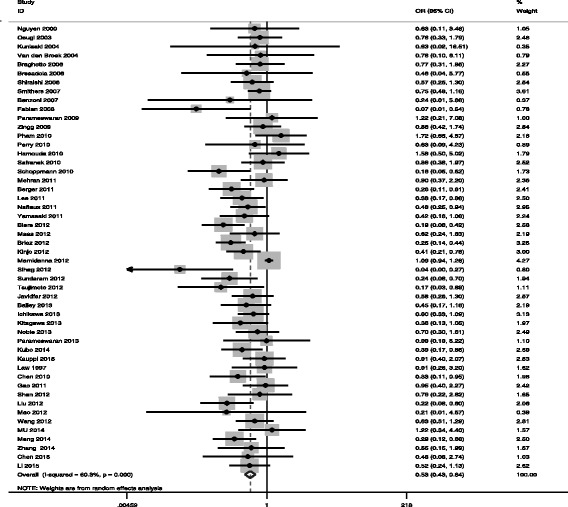

Fifty studies including 14,781 cases reported pulmonary complications, where 17.1% (813/4761) were in MIO group and 22.6% (2264/10,020) were in OE group, with overall morbidity of 20.8% (3077/14,781).

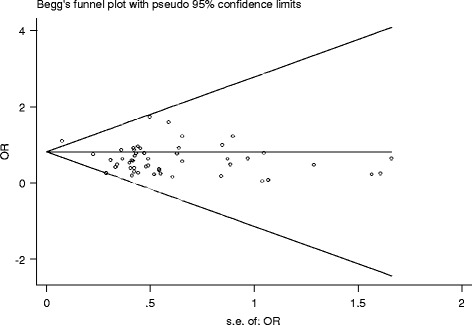

There was very strong evidence of reduced risk of pulmonary complications in the MIO group (OR = 0.527, 95%CI = 0.431 ~ 0.645, P V < 0.05), with statistical heterogeneity (I 2 of 60.3%, P Q = 0.012) (Fig. 3, Table 3). In order to find out other sources of heterogeneity, Galbraith Plot Analysis was performed to identify which study results in the heterogeneity (Fig. 4). Pham et al. [52] and Mamidanna et al. [66] were outliers from the Galbraith Plot Analysis and I 2 values decreased after removing the study (OR = 0.502 95% CI = 0.425 ~ 0.592, P V < 0.05, I 2 = 26.6%, P Q = 0.05). However, the funnel plot figure (Fig. 5) showed significant statistical difference (P E < 0.05), indicating the possibility of publication bias.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis for MIE and pulmonary complications

Fig. 4.

Galbraith plot of MIE and pulmonary complications

Fig. 5.

Begg’s Test of MIE and pulmonary complications

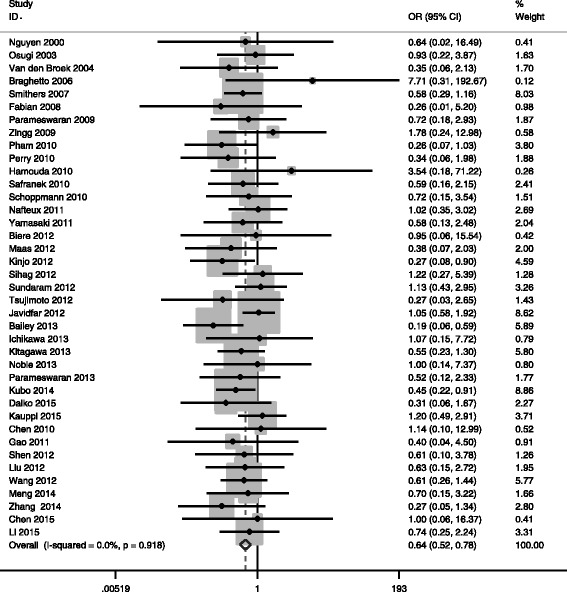

MIO and mortality

Thirty-eight studies addressed the mortality (MIO 4379 vs OE 9753). The mortality risk was 3.8% (124/4379) in MIO group versus 4.5% (437/9753) in OE group. There was very strong evidence of reduced mortality in MIO group (OR = 0.668, 95% CI = 0.539 ~ 0.827, P V < 0.05), with statistical homogeneity (I 2 of 0%, P Q = 0.944) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Meta-analysis for MIE and Mortality

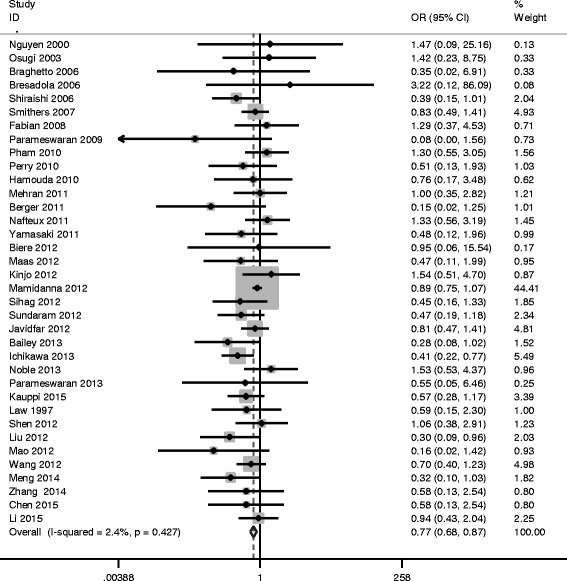

MIO and cardiovascular complications

Thirty-six studies reported cardiovascular complications (MIO 3745 vs OE 9138). There was very strong evidence of reduced cardiovascular complications in MIO group (OR = 0.770, 95% CI = 0.681 ~ 0.872, P V < 0.05), with statistical homogeneity (I 2 of 2.4%, P Q = 0.427) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Meta-analysis of MIE and cardiovascular complications

MIO and surgical technology related (STR) complications

Thirty-nine studies reported STR complications (MIO2933 vs OE 3058). There was very strong evidence of reduced STR complications in MIO group (OR = 0.770, 95% CI = 0.681 ~ 0.872, P V < 0.05), with statistical homogeneity (I 2 of 2.4%, P Q = 0.918) (Fig. 8 and Table 3).

Fig. 8.

Meta-analysis of MIE and STR complications

MIO and gastrointestinal complications

Twenty-one studies reported gastrointestinal complications (MIO 1872 vs OE 2209). There was no evidence of reduced gastrointestinal complications in MIO group (OR = 1.097, 95% CI = 0.835 ~ 1.442, P V = 0.507), with statistical homogeneity (I 2 of 31.7%, P Q = 0.083) (Table 3).

MIO and anastomotic leak (AL)

Fifty studies reported anastomotic leak (MIO 3680 vs OE 3848). There was no evidence of reduced anastomotic leak in MIO group (OR = 1.023, 95% CI = 0.870 ~ 1.202, P V = 0.785), with statistical homogeneity (I 2 of 8.5%, P Q = 0.304) (Table 3).

MIO and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (RLNP)

Thirty-seven studies reported recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (MIO 2624 vs OE 2805). There was no evidence of reduced RLNP in MIO group (OR = 1.108, 95% CI = 0.917 ~ 1.339, P V = 0.289), with statistical homogeneity (I 2 of 24.8%, P Q = 0.089) (Table 3).

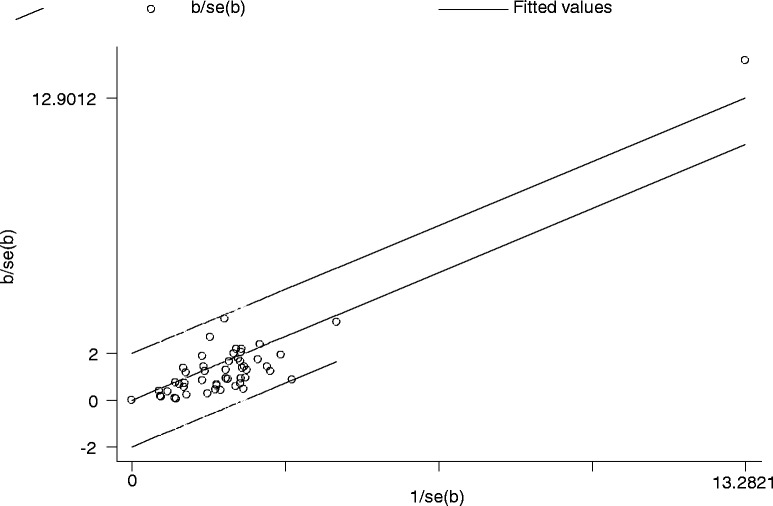

Publication bias analysis

Publication bias was assessed by Egger’s Test and Begg’s Funnel Plot. Begg’s Funnel Plot is shown in Fig. 5, with significant statistical difference (P E < 0.05) (Table 3). This indicated the possibility of publication bias, so sensitivity analysis using “trim and fill” method was carried out, with the aim to impute hypothetically negative unpublished studies, to mirror the positive studies that cause funnel plot asymmetry [35], and to show consistent and stable results between MIO and pulmonary complications (Fig. 9), anastomotic leak, and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy.

Fig. 9.

The “trim and fill” method for MIE and pulmonary complications

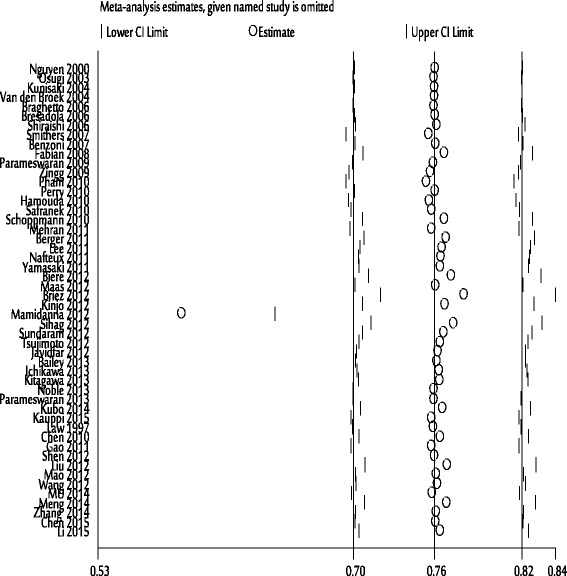

Sensitivity analysis

As sample size for cases and controls in all studies is not same (ranging from 9 to 6347), we gradually removed small sample size without altering the qualitative overall results. According to the sensitivity analysis shown in Fig. 10, we removed the Mamidanna et al. [66], without alteration, where I 2 values decreased, indicating that the results were stable.

Fig. 10.

The sensitivity analysis of MIE and pulmonary complications

Discussion

MIO has been investigated for decades and is considered to be advantageous compared to OE. However, in the previous studies, the analyzed groups of patients who underwent MIO were small and the reports were mostly retrospective comparative studies, and there was no consensus as to which operative method is superior [94]. Therefore, an updated meta-analysis is performed, which includes the largest and the most complete collections of published data.

We found higher operative duration in the MIO group, consistent with Kunisaki’s [40], Shiraishi’s [45], and randomized controlled trials [30] reported, perhaps due to surgeons’ familiarization with a new and complex techniques. Blood loss in the MIO group was found to be lower compared with OE, in accordance with the results of several case reported and recently published meta-analyses [14, 20].

A shorter hospital stay in the MIO group indicated a faster postoperative recovery than OE group, consistent with other published meta-analyses [14, 20, 21, 30].

We did not find a significant number of harvested lymph nodes in the MIO group [23]. However, significant heterogeneity was seen among all indices of postoperative data, explained by the fact that postoperative data are dependent on operator and tumor characteristics.

Total complication rates varied between 20.5 and 63.5% (Table 2). The MIO group showed lower total complication rates, pulmonary complications occupying the major part. However, a number of studies have reported significantly lower pulmonary complications for those who underwent MIO 17.1% (813/4761) versus OE 22.6% (2264/10,020), with overall morbidity of 20.8% (3077/14,781), consistent with the result of 3.1–37.0% from other studies [15–20, 45, 58–76, 95].

Kinugasa et al. and Ferguson et al. [95, 96] noted that development of pneumonia post procedure was associated with worse prognosis for overall survival (P < 0.01). In addition, Dumont et al. [97] also showed that two thirds of all fatal complications were respiratory in nature. Sauvanet et al. [98] reported that pulmonary morbidity was associated with age >60, with no significant differences in two groups.

The pooled OR of 0.527 showed MIO to be more advantageous than OE in reducing pulmonary morbidity. Although statistical heterogeneity and publication bias were found, we demonstrated the superiority of MIO through statistical methods. However, several factors have been associated with pulmonary complications post procedure, including preoperative status, intraoperative details, and postoperative details [99].

Gex et al. reported that overall 30-day mortality rate was 4.3% between 2004 and 2009, compared with 7.6% in 2002 and 2003, and 11.7% in 1997 and 1999 [100]. Our study found the overall 30-day mortality rate of 5.8% and the pooled OR of 0.668, showing that MIO to be advantageous than OE in reducing mortality. The main advantages of MIO over conventional OE are minimal trauma, small incision, less blood loss, etc. [6]. Other factors independently associated with 30-day mortality included TNM staging, preoperative neoadjuvant therapy, comorbidity, diabetes, increased age, and intraoperative blood loss. However, there was no difference between two groups in terms of age and comorbidity. We found increased number of patients having neoadjuvant therapy in MIO group and patients selected for MIO were always in the early stages. The bias in the selection of patients may have influenced the accuracy of the conclusion, which should be taken into consideration.

Arrhythmia, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and other cardiovascular complications are recognized as common problems that caused significant morbidity and mortality. Zhou et al. [24] reported significant decrease in the morbidity of arrhythmia and pulmonary embolism in MIO group. Corresponding to this, (see Table 3), we found MIO to be superior to OE in reducing morbidity of system complications, according to the pooled OR = 0.777. Weidenhagent et al. [101] also indicated that the perforation from minimally invasive surgery as such could decrease the risks leading to arrhythmia.

Rizk et al. [102] indicated that “surgical technology related complications,” defined as complications caused directly by operative techniques, had no relationship with overall survival post procedure. However, in our meta-analysis, we found strong evidence of reduced risk of STR complications in the MIO group.

Anastomotic leakage (AL) is a serious complication of esophageal resection and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [4]. In accordance with Zhou et al’s conclusion [17], we also did not find the evidence of reduced risk of anastomotic leak in the MIO group. Similarly, we also did not find any significant differences in two groups in terms of RLNP and gastrointestinal complications.

Although we conducted comprehensive meta-analysis, our study still has its limitations. (1) Out of 57 studies, only one study is randomized controlled trial (RCT), while others were case-control or cross-sectional designs. Seven studies were of small sample size, which might have influenced the final results of our study. (2) Patients selected for MIO are unlikely to have been representative of the general population of esophageal cancer. We found more patients having neoadjuvant therapy in MIO group, and the patients selected for MIO were always in the early stages, creating selection bias. (3) In order to highlight the advantages of MIO, surgeons would prefer to publish positive results, and unsatisfactory results may have been less inclined in their papers; all these can lead to publication bias. (4) In our study, we compared MIO with OE. MIO consists of different procedures. Although we performed a subgroup analysis according to different procedures, the results were also not qualitatively altered. However, lots of differences exist among these procedures, which will affect the quality of this meta-analysis, and the learning curve of MIO is quite steep, which may influence the outcome of MIE. These limitations may result in an overestimation or underestimation of the effect of MIO.

In addition, 19 studies did the follow-up visit, and all those studies indicated that the 3-year survival, 5-year survival, and overall recurrence rate did not differ between the two groups. Due to the difficulty in data extraction, no pooled analysis was performed, which may have influential role in this study.

Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis indicates that MIO is a feasible and a reliable surgical procedure and is superior to OE, with less perioperative complications and in-hospital mortality. However, due to certain limitations of this study, as aforementioned above, further large sample and RCT studies are needed to estimate the effect of MIO and establish the guidelines for future.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors declare no funding disclosures or sponsors to this study.

Availability of data and materials

The database supporting the conclusion of this article is included within the article and its additional files (fig file and table file).

Authors’ contributions

YW collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. WS contributed to the designing, writing, and editing of the manuscript, searching for and adding references, and correspondence with the co-authors. AS and HL offered the technical or material support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MIE

Minimally invasive esophagectomy

- MIO

Minimally invasive oesophagectomy

- OE

Open esophagectomy

- RLNP

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

- STR

Surgical technology related

- TA

Thoracoscopic assisted

Contributor Information

Waresijiang Yibulayin, Email: wzs881117@163.com.

Sikandaer Abulizi, Email: dongm311400@sina.com.

Hongbo Lv, Email: lih471003@sina.com.

Wei Sun, Email: yuan2559052@163.com.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:33–64. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schweigert M, Dubecz A, Stadlhuber RJ, Muschweck H, Stein HJ. Treatment of intrathoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks by means of endoscopic stent implantation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:147–151. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.247866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morita M, Nakanoko T, Fujinaka Y, Kubo N, Yamashita N, Yoshinaga K, Saeki H, Emi Y, Kakeji Y, Shirabe K, Maehara Y. In-hospital mortality after a surgical resection for esophageal cancer: analyses of the associated factors and historical changes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1757–1765. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, Stalmeier PF, Ten KF, van Dekken H, Obertop H, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1662–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luketich JD, Alvelo-Rivera M, Buenaventura PO, Christie NA, McCaughan JS, Litle VR, Schauer PR, Close JM, Fernando HC. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: outcomes in 222 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;238:486–494. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089858.40725.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Birkmeyer JD. Are mortality rates for different operations related?: implications for measuring the quality of noncardiac surgery. Med Care. 2006;44:774–778. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215898.33228.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earlam R, Cunha-Melo JR. Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: I. A critical review of surgery. Br J Surg. 1980;67:381–390. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800670602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoppo T, Jobe BA, Hunter JG. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: The evolution and technique of minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:1454–63. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto M, Weber JM, Karl RC, Meredith KL. Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer: review of the literature and institutional experience. Cancer Control. 2013;20:130–137. doi: 10.1177/107327481302000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkaria IS, Rizk NP. Robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy: the Ivor Lewis approach. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Journo XB, Thomas PA. Current management of esophageal cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(Suppl 2):S253–S264. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.04.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhamija A, Dhamija A, Hancock J, McCloskey B, Kim AW, Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy more expensive than open despite shorter length of stay. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:904–909. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhage RJ, Hazebroek EJ, Boone J, Van Hillegersberg R. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open procedures in esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Minerva Chir. 2009;64:135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Ma X, Yang S, Zhu X, Qin W, Xiang J, Lerut T, Li H. Combined thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy versus open esophagectomy: a meta-analysis of outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2016;18(9):5–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markar SR, Arya S, Karthikesalingam A, Hanna GB. Technical factors that affect anastomotic integrity following esophagectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4274–4281. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou C, Ma G, Li X, Li J, Yan Y, Liu P, He J, Ren Y. Is minimally invasive esophagectomy effective for preventing anastomotic leakages after esophagectomy for cancer?A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:269. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0661-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gemmill EH, McCulloch P. Systematic review of minimally invasive resection for gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1461–1467. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biere SS, Cuesta MA, van der Peet DL. Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Chir. 2009;64:121–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagpal K, Ahmed K, Vats A, Yakoub D, James D, Ashrafian H, Darzi A, Moorthy K, Athanasiou T. Is minimally invasive surgery beneficial in the management of esophageal cancer? A meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1621–1629. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sgourakis G, Gockel I, Radtke A, Musholt TJ, Timm S, Rink A, Tsiamis A, Karaliotas C, Lang H. Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy: meta-analysis of outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3031–3040. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler N, Collins S, Memon B, Memon MA. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy: current status and future direction. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2071–2083. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dantoc MM, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Does minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) provide for comparable oncologic outcomes to open techniques? A systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:486–494. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou C, Zhang L, Wang H, Ma X, Shi B, Chen W, He J, Wang K, Liu P, Ren Y. Superiority of minimally invasive oesophagectomy in reducing in-hospital mortality of patients with resectable oesophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e132889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dantoc M, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Evidence to support the use of minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2012;147:768–776. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumer E, Perry K, Melvin WS. Minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: evolution and review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:383–386. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31826295a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe M, Baba Y, Nagai Y, Baba H. Minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: an updated review. Surg Today. 2013;43:237–244. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uttley L, Campbell F, Rhodes M, Cantrell A, Stegenga H, Lloyd-Jones M. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy versus open surgery: is there an advantage? Surg Endosc. 2013;27:724–731. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs M, Macefield RC, Elbers RG, Sitnikova K, Korfage IJ, Smets EM, Henselmans I, van Berge HM, de Haes JC, Blazeby JM, Sprangers MA. Meta-analysis shows clinically relevant and long-lasting deterioration in health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1097–1115. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biere SS, van Berge HM, Maas KW, Bonavina L, Rosman C, Garcia JR, Gisbertz SS, Klinkenbijl JH, Hollmann MW, de Lange ES, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298:2654–2664. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studiesinmeta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 2 Dec 2016.

- 37.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen NT, Follette DM, Wolfe BM, Schneider PD, Roberts P, Goodnight JJ. Comparison of minimally invasive esophagectomy with transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135:920–925. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.8.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osugi H, Takemura M, Higashino M, Takada N, Lee S, Kinoshita H. A comparison of video-assisted thoracoscopic oesophagectomy and radical lymph node dissection for squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus with open operation. Br J Surg. 2003;90:108–113. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunisaki C, Hatori S, Imada T, Akiyama H, Ono H, Otsuka Y, Matsuda G, Nomura M, Shimada H. Video-assisted thoracoscopic esophagectomy with a voice-controlled robot: the AESOP system. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004;14:323–327. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000148468.74546.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernabe KQ, Bolton JS, Richardson WS. Laparoscopic hand-assisted versus open transhiatal esophagectomy: a case–control study. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:334–337. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8807-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van den Broek WT, Makay O, Berends FJ, Yuan JZ, Houdijk AP, Meijer S, Cuesta MA. Laparoscopically assisted transhiatal resection for malignancies of the distal esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:812–817. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9173-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braghetto I, Csendes A, Cardemil G, Burdiles P, Korn O, Valladares H. Open transthoracic or transhiatal esophagectomy versus minimally invasive esophagectomy in terms of morbidity, mortality and survival. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1681–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bresadola V, Terrosu G, Cojutti A, Benzoni E, Baracchini E, Bresadola F. Laparoscopic versus open gastroplasty in esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a comparative study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:63–67. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiraishi T, Kawahara K, Shirakusa T, Yamamoto S, Maekawa T. Risk analysis in resection of thoracic esophageal cancer in the era of endoscopic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1083–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Martin I, Thomas JM. Comparison of the outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;245:232–240. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225093.58071.c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benzoni E, Terrosu G, Bresadola V, Uzzau A, Intini S, Noce L, Cedolini C, Bresadola F, De Anna D. A comparative study of the transhiatal laparoscopic approach versus laparoscopic gastric mobilisation and right open transthoracic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer management. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fabian T, Martin JT, McKelvey AA, Federico JA. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: a teaching hospital's first year experience. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parameswaran R, Veeramootoo D, Krishnadas R, Cooper M, Berrisford R, Wajed S. Comparative experience of open and minimally invasive esophagogastric resection. World J Surg. 2009;33:1868–1875. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saha AK, Sutton CD, Sue-Ling H, Dexter SP, Sarela AI. Comparison of oncological outcomes after laparoscopic transhiatal and open esophagectomy for T1 esophageal adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:119–124. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zingg U, McQuinn A, DiValentino D, Esterman AJ, Bessell JR, Thompson SK, Jamieson GG, Watson DI. Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pham TH, Perry KA, Dolan JP, Schipper P, Sukumar M, Sheppard BC, Hunter JG. Comparison of perioperative outcomes after combined thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy and open Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy. Am J Surg. 2010;199:594–598. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perry KA, Enestvedt CK, Pham T, Welker M, Jobe BA, Hunter JG, Sheppard BC. Comparison of laparoscopic inversion esophagectomy and open transhiatal esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia and stage I esophageal adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 2009;144:679–684. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamouda AH, Forshaw MJ, Tsigritis K, Jones GE, Noorani AS, Rohatgi A, Botha AJ. Perioperative outcomes after transition from conventional to minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy in a specialized center. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:865–869. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Safranek PM, Cubitt J, Booth MI, Dehn TC. Review of open and minimal access approaches to oesophagectomy for cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1845–1853. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schoppmann SF, Prager G, Langer FB, Riegler FM, Kabon B, Fleischmann E, Zacherl J. Open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy: a single-center case controlled study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3044–3053. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schroder W, Holscher AH, Bludau M, Vallbohmer D, Bollschweiler E, Gutschow C. Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy with and without laparoscopic conditioning of the gastric conduit. World J Surg. 2010;34:738–743. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0403-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehran R, Rice D, El-Zein R, Huang JL, Vaporciyan A, Goodyear A, Mehta A, Correa A, Walsh G, Roth J, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy versus open esophagectomy, a symptom assessment study. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berger AC, Bloomenthal A, Weksler B, Evans N, Chojnacki KA, Yeo CJ, Rosato EL. Oncologic efficacy is not compromised, and may be improved with minimally invasive esophagectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee JM, Cheng JW, Lin MT, Huang PM, Chen JS, Lee YC. Is there any benefit to incorporating a laparoscopic procedure into minimally invasive esophagectomy? The impact on perioperative results in patients with esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:790–797. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nafteux P, Moons J, Coosemans W, Decaluwe H, Decker G, De Leyn P, Van Raemdonck D, Lerut T. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy: a valuable alternative to open oesophagectomy for the treatment of early oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal junction carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1455–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Fujiwara Y, Takiguchi S, Nakajima K, Kurokawa Y, Mori M, Doki Y. Minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: comparative analysis of open and hand-assisted laparoscopic abdominal lymphadenectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:623–628. doi: 10.1002/jso.21991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maas KW, Biere SS, Scheepers JJ, Gisbertz SS, Van-der-Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Laparoscopic versus open transhiatal esophagectomy for distal and junction cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2012;104:197–202. doi: 10.4321/S1130-01082012000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Briez N, Piessen G, Torres F, Lebuffe G, Triboulet JP, Mariette C. Effects of hybrid minimally invasive oesophagectomy on major postoperative pulmonary complications. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1547–1553. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kinjo Y, Kurita N, Nakamura F, Okabe H, Tanaka E, Kataoka Y, Itami A, Sakai Y, Fukuhara S. Effectiveness of combined thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy: comparison of postoperative complications and midterm oncological outcomes in patients with esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1883-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Faiz O, Hanna GB. Short-term outcomes following open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer in England: a population-based national study. Ann Surg. 2012;255:197–203. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823e39fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sihag S, Wright CD, Wain JC, Gaissert HA, Lanuti M, Allan JS, Mathisen DJ, Morse CR. Comparison of perioperative outcomes following open versus minimally invasive Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy at a single, high-volume centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:430–437. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sundaram A, Geronimo JC, Willer BL, Hoshino M, Torgersen Z, Juhasz A, Lee TH, Mittal SK. Survival and quality of life after minimally invasive esophagectomy: a single-surgeon experience. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:168–176. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsujimoto H, Takahata R, Nomura S, Yaguchi Y, Kumano I, Matsumoto Y, Yoshida K, Horiguchi H, Hiraki S, Ono S, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal cancer attenuates postoperative systemic responses and pulmonary complications. Surgery. 2012;151:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Javidfar J, Bacchetta M, Yang JA, Miller J, D'Ovidio F, Ginsburg ME, Gorenstein LA, Bessler M, Sonett JR. The use of a tailored surgical technique for minimally invasive esophagectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:1125–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bailey L, Khan O, Willows E, Somers S, Mercer S, Toh S. Open and laparoscopically assisted oesophagectomy: a prospective comparative study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:268–273. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ichikawa H, Miyata G, Miyazaki S, Onodera K, Kamei T, Hoshida T, Kikuchi H, Kanba R, Nakano T, Akaishi T, Satomi S. Esophagectomy using a thoracoscopic approach with an open laparotomic or hand-assisted laparoscopic abdominal stage for esophageal cancer: analysis of survival and prognostic factors in 315 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:873–885. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826c87cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kitagawa H, Namikawa T, Iwabu J, Akimori T, Okabayashi T, Sugimoto T, Mimura T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Efficacy of laparoscopic gastric mobilization for esophagectomy: comparison with open thoraco-abdominal approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:452–455. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noble F, Kelly JJ, Bailey IS, Byrne JP, Underwood TJ. A prospective comparison of totally minimally invasive versus open Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parameswaran R, Titcomb DR, Blencowe NS, Berrisford RG, Wajed SA, Streets CG, Hollowood AD, Krysztopik R, Barham CP, Blazeby JM. Assessment and comparison of recovery after open and minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer: an exploratory study in two centers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1970–1977. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2848-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takeno S, Takahashi Y, Moroga T, Kawahara K, Yamashita Y, Ohtaki M. Retrospective study using the propensity score to clarify the oncologic feasibility of thoracoscopic esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:1673–1680. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kubo N, Ohira M, Yamashita Y, Sakurai K, Toyokawa T, Tanaka H, Muguruma K, Shibutani M, Yamazoe S, Kimura K, et al. The impact of combined thoracoscopic and laparoscopic surgery on pulmonary complications after radical esophagectomy in patients with resectable esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:2399–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schneider C, Boddy AP, Fukuta J, Groom WD, Streets CG. Predicting blood transfusion in patients undergoing minimally invasive oesophagectomy. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1342–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Daiko H, Fujita T. Laparoscopic assisted versus open gastric pull-up following thoracoscopic esophagectomy: A cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;19:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kauppi J, Rasanen J, Sihvo E, Huuhtanen R, Nelskyla K, Salo J. Open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy: clinical outcomes for locally advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2614–2619. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3978-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Law S. Minimally invasive techniques for oesophageal cancer surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:925–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen BF, Zhu CC, Wang CG, Ma DH, Lin J, Zhang B, Kong M. Clinical comparative study of minimally invasive esophagectomy versus open esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;48:1206–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao Y, Wang Y, Chen L, Zhao Y. Comparison of open three-field and minimally-invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:366–369. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.258632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shen Y, Zhang Y, Tan L, Feng M, Wang H, Khan MA, Liang M, Wang Q. Extensive mediastinal lymphadenectomy during minimally invasive esophagectomy: optimal results from a single center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:715–721. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu BX, Li Y, Qin JJ, Zhang RX, Liu XB, Sun HB, Liu SL. Comparison of thoraco-laparoscopic and open three-field subtotal esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;15:938–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mao T, Fang WT, Gu ZT, Yao F, Guo XF, Chen WH. Comparative study of perioperative complications and lymphadenectomy between minimally invasive esophagectomy and open procedure. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;15:922–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang H, Tan LJ, Li JP, Shen YX, Zhang Y, Feng MX, Wang Q. Evaluation of safety of video-assisted thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;15:926–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mu J, Yuan Z, Zhang B, Li N, Lyu F, Mao Y, Xue Q, Gao S, Zhao J, Wang D, et al. Comparative study of minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in a single cancer center. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:747–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meng F, Li Y, Ma H, Yan M, Zhang R. Comparison of outcomes of open and minimally invasive esophagectomy in 183 patients with cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:1218–1224. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.07.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang J, Xu M, Guo M, Mei X, Liu C. Analysis of postoperative quality of life in patients with middle thoracic esophageal carcinoma undergoing minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2014;17:915–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen X, Yang J, Peng J, Jiang H. Case-matched analysis of combined thoracoscopic-laparoscopic versus open esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:13516–13523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang J, Lyu B, Zhu W, Chen J, He J, Tang S. A retrospective cohort comparison of esophageal carcinoma between thoracoscopic and laparoscopic esophagectomy and open esophagectomy. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;53:378–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li J, Shen Y, Tan L, Feng M, Wang H, Xi Y, Wang Q. Is minimally invasive esophagectomy beneficial to elderly patients with esophageal cancer? Surg Endosc. 2015;29:925–930. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3753-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wallner G, Zgodzinski W, Masiak-Segit W, Skoczylas T, Dabrowski A. Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer - benefits and controversies. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2014;11:151–155. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2014.43842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ferguson MK, Durkin AE. Preoperative prediction of the risk of pulmonary complications after esophagectomy for cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:661–669. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.120350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kinugasa S, Tachibana M, Yoshimura H, Ueda S, Fujii T, Dhar DK, Nakamoto T, Nagasue N. Postoperative pulmonary complications are associated with worse short- and long-term outcomes after extended esophagectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:71–77. doi: 10.1002/jso.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dumont P, Wihlm JM, Hentz JG, Roeslin N, Lion R, Morand G. Respiratory complications after surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. A study of 309 patients according to the type of resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1995;9:539–543. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(05)80001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sauvanet A, Mariette C, Thomas P, Lozac'H P, Segol P, Tiret E, Delpero JR, Collet D, Leborgne J, Pradere B, et al. Mortality and morbidity after resection for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: predictive factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.D'Amico TA. Outcomes after surgery for esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2007;1:188–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gex G, Gerstel E, Righini M, LE Gal G, Aujesky D, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Verschuren F, Rutschmann OT, Perneger T, Perrier A. Is atrial fibrillation associated with pulmonary embolism? J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weidenhagen R, Hartl WH, Gruetzner KU, Eichhorn ME, Spelsberg F, Jauch KW. Anastomotic leakage after esophageal resection: new treatment options by endoluminal vacuum therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1674–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rizk NP, Bach PB, Schrag D, Bains MS, Turnbull AD, Karpeh M, Brennan MF, Rusch VW. The impact of complications on outcomes after resection for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The database supporting the conclusion of this article is included within the article and its additional files (fig file and table file).