Abstract

The aim of this study was to compare the effect of two different training programmes – change of direction (COD) vs. agility (AG) – on straight sprint (SS), COD and AG test performances in young elite soccer players. Thirty-two soccer players (age: 14.5±0.9 years; height: 171.2±5.1 cm; body mass: 56.4±7.1 kg, body fat: 10.3±2.3%) participated in a short-term (6 weeks) training study. Players were randomly assigned to two experimental groups – training with change of direction drills (COD-G, n=11) or using agility training (AG-G, n= 11) – and to a control group (CON-G, n=10). All players completed the following tests before and after training: straight sprint (15m SS), 15 m agility run with (15m-AR-B) and without a ball (15m-AR), 5-0-5 agility test, reactive agility test (RAT), and RAT test with ball (RAT-B). A significant group effect was observed for all tests (p<0.001; η2=large). In 15m SS, COD-G and AG-G improved significantly (2.21; ES=0.57 and 2.18%; ES=0.89 respectively) more than CON-G (0.59%; ES=0.14). In the 15m-AR and 5-0-5 agility test, COD-G improved significantly more (5.41%; ES=1.15 and 3.41; ES=0.55 respectively) than AG-G (3.65%; ES=1.05 and 2.24; ES=0.35 respectively) and CON-G (1.62%; ES=0.96 and 0.97; ES=0.19 respectively). Improvements in RAT and RAT-B were larger (9.37%; ES=2.28 and 7.73%; ES=2.99 respectively) in RAT-G than the other groups. In conclusion, agility performance amongst young elite soccer could be improved using COD training. Nevertheless, including a conditioning programme for agility may allow a high level of athletic performance to be achieved.

Keywords: Reaction time, Turns, Training, Soccer, Decision-making

INTRODUCTION

Success in soccer requires high levels of technical, tactical, psychological and physical skills including aerobic and anaerobic power, muscle strength, flexibility and agility [1]. During a soccer game, players perform repeated bouts of low-level activity such as walking, jogging or cruising in conjunction with high-intensity actions such as sprinting, jumping and directional changes [2]. The ability to sprint, accelerate and decelerate alongside change of direction is commonly known as agility. Agility has been, indeed, defined as a rapid whole-body movement with change of velocity or direction in response to a “stimulus” [3]. Adhering to this definition, it is well recognized that agility is composed of perceptual and decision making factors, as well as change of direction (COD) components [4]. According to the scientific literature, agility is suggested as an important physical quality which should be well developed throughout childhood and adolescence [5]. Indeed, during this stage many body modifications emerge such as increase in sex androgen concentrations, increase of muscle cross-sectional area, nervous system development and neuro-plasticity adaptations [6].

Referring to the model proposed by Young et al. [4], COD speed is influenced by several factors such as straight sprint (SS), leg muscle qualities (i.e. strength, power and reactive strength) and running technique. Therefore, in order to improve COD ability, many studies have proposed training programmes with planned activities (closed skills) based on the development of these determinant factors. In the last decades, the scientific literature has shown controversial findings in that regard. Indeed, some studies revealed that SS-based training enhanced COD performance [7, 8], while Young et al. [9] reported no significant improvements for similar training settings. Likewise, the effects of strength training either with power, plyometric or maximal strength training remain debatable [10–12]. Consequently, in order to optimize performance, it has been recommended to use a mixed training programme that includes sprint, agility and quickness (SAQ) exercises [12–18]. Nevertheless, the results of these recommendations still led to contradictory results, since some studies reported significant improvements in COD performance [14, 16, 19- 21], while others indicated no effect [12, 17, 18, 22].

Currently, there is a lack of scientific investigations conducted concerning the effectiveness of agility (AG) training with generic or specific exercises [23, 24]. Serpell et al. [24] reported an improvement of AG test performance among rugby players following a training programme designed to enhance perceptual and decision-making ability. Nowadays, specific training programmes that require reacting to a “specific stimulus” such as the position of the ball or the position of the opponent and/or the teammate have been proposed [18, 23]. In this context, small-sided games (SSGs) have emerged, since they represent typical exercises for soccer players as they mimic the specific actions of soccer games. Young and Rogers [18] found that SSGs improved AG performance in Australian football players. Likewise, Chaouachi et al. [23] reported that agility could be improved using SSGs or COD sprints in young male soccer players.

To align with the specificity principle, training sessions’ content and design should focus on player preparation by improving their capability to respond and react to competitive game situations. However, optimally improving AG through the stimulation of physical and cognitive skills remains unclear. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no research comparing change of direction (COD) and agility (AG) testing and training (with ball and without ball) exists amongst the same assessed population. Therefore, the present study examined the effects of two different training programmes – AG vs COD – on the performance of speed, COD, and agility tests among elite youth soccer players. The results of this study will allow strength and conditioning coaches to develop an appropriate training programme for improving COD and AG skills.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

Two programmes based on COD and AG were performed in young elite soccer players. Participants completed a battery of tests before and after 6 weeks of training. The soccer players were randomly separated into 2 experimental groups: 1) the change of direction group (COD-G), and 2) the agility group (A-G). A control group (CON-G) recruited from the same team was also tested and was instructed to continue with daily activities but not to undertake any additional training other than the team soccer training. Players were asked to wear adapted soccer boots (adapted to the turf and allowing players to have good adherence to the pitch) in a consistent way through the experiment.

Participants

Thirty-two young male elite soccer players were randomly separated into 3 groups (two experimental groups and one control group). All participants (age: 14.5±0.9 years; height: 171.2±5.1 cm; body mass: 56.4±7.1 kg, body fat: 10.3±2.3%) had at least 4 years of soccer practice in the first division of the national soccer league of Tunisia. All players trained five times a week (i.e. ~90 min per session) with one match played during the weekend over the entire training period. Testing sessions were administered during the competition phase (fifth month of the season). The experimental groups consisted of 22 players who were randomly assigned to 2 groups: the change of direction group (COD-G; n = 11) and the agility group (AG-G; n= 11). Ten players were defined as the control group, while goalkeepers were not included in the investigation. Written informed consent was obtained from all the players and their guardian/parents after receiving verbal and written information about the nature and the associated risks and benefits involved in this study. Familiarization procedures for testing were performed one week before the beginning of the protocol by all recruited players. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was fully approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tunisian National Centre of Medicine and Science of Sports (CNMSS) before the beginning of the protocol.

Testing procedures

Field tests were carried out on a third-generation synthetic soccer turf. The testing session was started after ~12 minutes of supervised warm-up including skipping exercises, preparatory sprint drills, and 2 practice sprints in the test courses at about 95% of maximum speed. Pre- and post-tests were performed on the same weekday between 5 pm and 7 pm, and at least 24 hours after the last training session and 2 hours after the last intake of food. All tests were performed on the pitch and under similar environmental conditions (i.e. temperature within 20-22°C, humidity within 65-70%, with no rain and non-windy conditions [wind speed under 10 km/h]).

Field tests

COD performance was assessed using the 5-0-5 test [25] and 15-m AR (with and without the ball) according to Mujika et al. [26]. AG with a ball (RAT-B) or without a ball (RAT) was assessed according to scientific literature [23, 27]. The 15m SS test was performed according to Mujika et al. [26]. All the tests were timed with photocell gates (Brower Timing Systems, Salt Lake City, USA). Players performed two trials of each test (2-min rest between trials) and the best performance was used for analysis (ICC: 0.90 to 0.98; SEM: 0.004 to 0.05; CV: 0.89 to 2.10).

15-m straight sprint run test

Each participant was asked to sprint a 15 m distance, with photocell gates placed 0.4 m above the ground. Sprint tests were performed with the players starting in a standing position, with their preferred foot forward and placed exactly 3 m behind the first timing gate.

15-m agility run test

As in the 15-m sprint test, players started running 3 m behind the initial set of gates. After 3 m of straight running, players entered a 3-m slalom section marked by three aligned sticks (at the height of 1.6 m) placed 1.5 m apart, and then cleared a 0.5-m hurdle placed 2 m beyond the third stick. Players finally ran 7 m to break the second set of photocell gates, which stopped the timer.

15-m ball dribbling

This test was similar to the 15-m agility run test, but players were required to dribble a ball while performing the test. After the slalom section of the test, the ball was kicked under the hurdle while the player cleared it. The player then kicked the ball towards either of two small goals placed diagonally 7 m on the left and the right sides of the hurdle, and finished with 7 m of straight sprint.

5-0-5 agility test

This test evaluated the capacity of the participants to quickly change direction. Markers were set up at 5 and 15 m from a line marked on the ground. The players assumed a starting position 10 m from the timing gates (i.e. 15 m from the turning point). The participants ran from the 15-m marker toward the line (running at distance to build up speed) and through the 5 m markers, turned on the line, and ran back through the 5-m markers. The time was recorded from when the participants first ran through the 5-m marker and stopped when they returned through these markers (i.e., the time taken to cover the 5 m up and back distance – 10 m total). The participants were instructed not to overstep the line by too much, as this would increase their test duration.

Reactive agility test (RAT)

The reactive agility test with (RAT-B) or without ball dribbling (RAT) was performed according to the protocol described previously by Chaouachi et al. [23]. During RATs the participant had four options:

Step forward with the right foot and change direction to the left.

Step forward with the left foot and change direction to the right.

Step forward with the right foot, then left foot, and change direction to the right.

Step forward with the left foot, then right foot, and change direction to the left.

All these conditions were provided to each player in 2 series (5-8 minute rest between sets) in a random order. Players were instructed to recognize the cues as soon as possible (essentially while moving forward). To increase consistency the mean of all trials (i.e. 8) was considered as the RAT performance.

Training programmes

The COD-G and the AG-G were required to participate in two additional training sessions per week (during a 6-week period) in addition to the usual training. Each training session lasted 20-25 min and included 3-4 COD exercises (1 to 6 COD/exercise) using various angles ranging from 45° to 180°. Recovery time of around 50 seconds was allowed between trials and 2-3 minutes between sets. COD and AG training programmes were designed to be equivalent with respect to the distances run, the total training volume, the number of agility modalities per player and per session, and the intensity of the efforts. The difference between COD and AG training programmes was the planned skills performed by COD-G, while only unplanned exercises were performed by AG-G (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Training exercises and distance progression for the COD and AG groups.

| Weeks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Exercise 1 | WB NB |

2*10m 2*10m |

2*10m 2*10m |

2*10m 2*10m |

2*10m 2*10m |

2*10m 2*10m |

2*10m 2*10m |

| Exercise 2 | WB NB |

3* 10m 3*10m |

3* 10m 3*10m |

3* 10m 3*10m |

3* 10m 3*10m |

3* 10m 3*10m |

3* 10m 3*10m |

| Exercise 3 | WB NB |

2*12m 2*12m |

2*12m 2*12m |

2*12m 2*12m |

2*12m 2*12m |

3*12m 3*12m |

3*12m 3*12m |

| Exercise 4 Total distance |

WB |

296m |

296m |

2*20m 376m |

2*20m 376m |

3*20m 424m |

3*20m 424m |

WB: with the ball; NB: without the ball; AG: agility; COD: change of direction

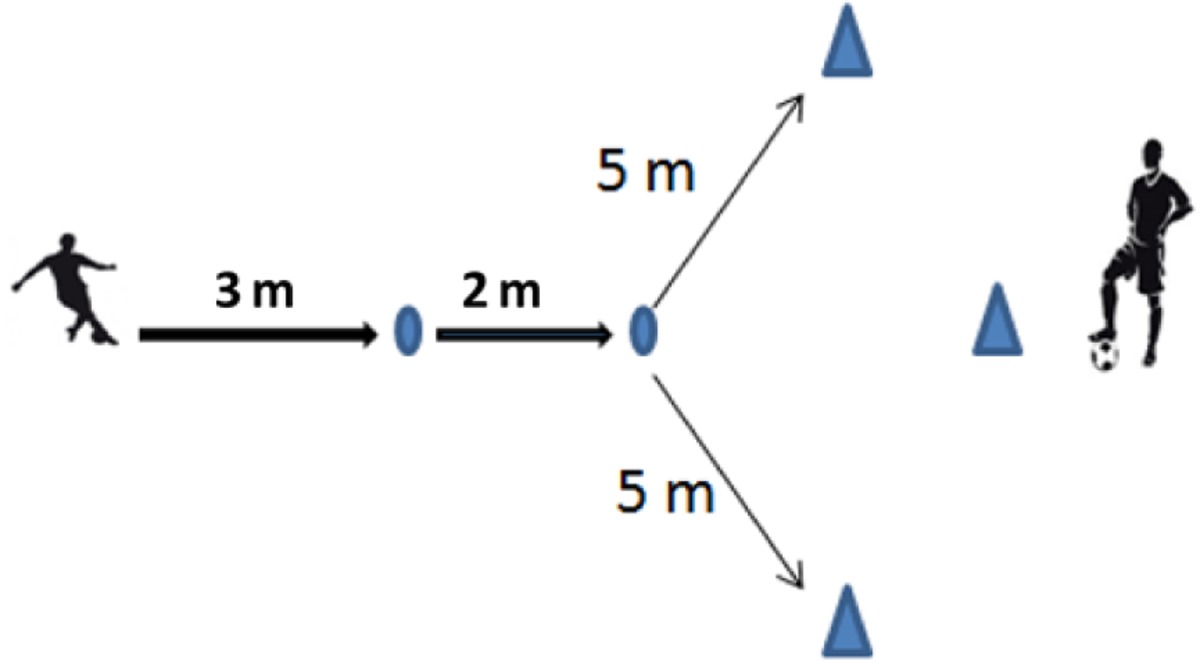

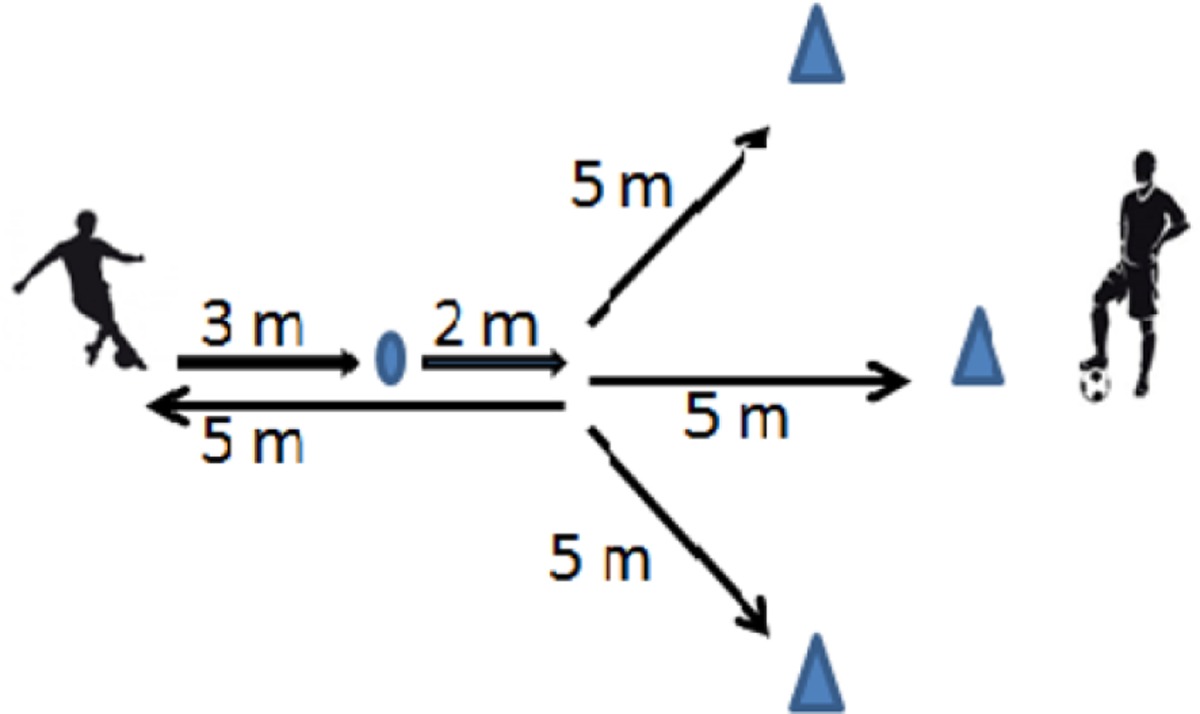

| Exercise 1: Drill starts with coach’s visual signal: ball touched with the insole of the coach’s foot. The player strongly accelerates towards the 5 m cone. As the player passes the 3 m distance the coach slightly moves the ball (around 20 cm aside) in the direction of the left or right cone. Upon this “second visual signal” the player quickly changes direction towards the indicated cone and continues his sprint until reaching the cone. WB: the exercise was performed with the player dribbling the ball from the start to the end. |  |

| Exercise 2: Same starting procedure as exercise 1. As the player passes the 3 m distance the coach moves the ball in a random direction and the player must immediately sprint to the nearest cone without loss of speed with four possible directions: forward, backwards, left, or right. Only the forward direction is not accompanied by a change of direction. WB: the exercise was performed with the player dribbling the ball from the start to the end. |  |

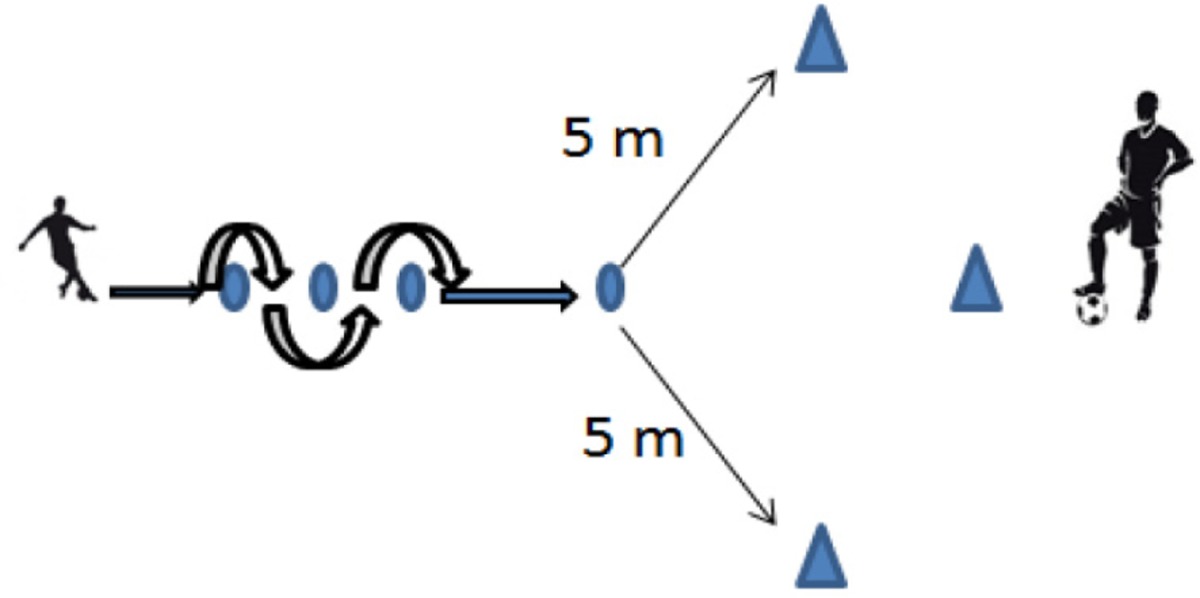

| Exercise 3 (COD and agility training): Drill performed with or without the ball, depending of the session objective. Same starting procedure as exercise 1. The player rapidly goes through the 3-m slalom, and then accelerates over a distance of 2 m before taking the right or left cone direction as in exercise 1. |  |

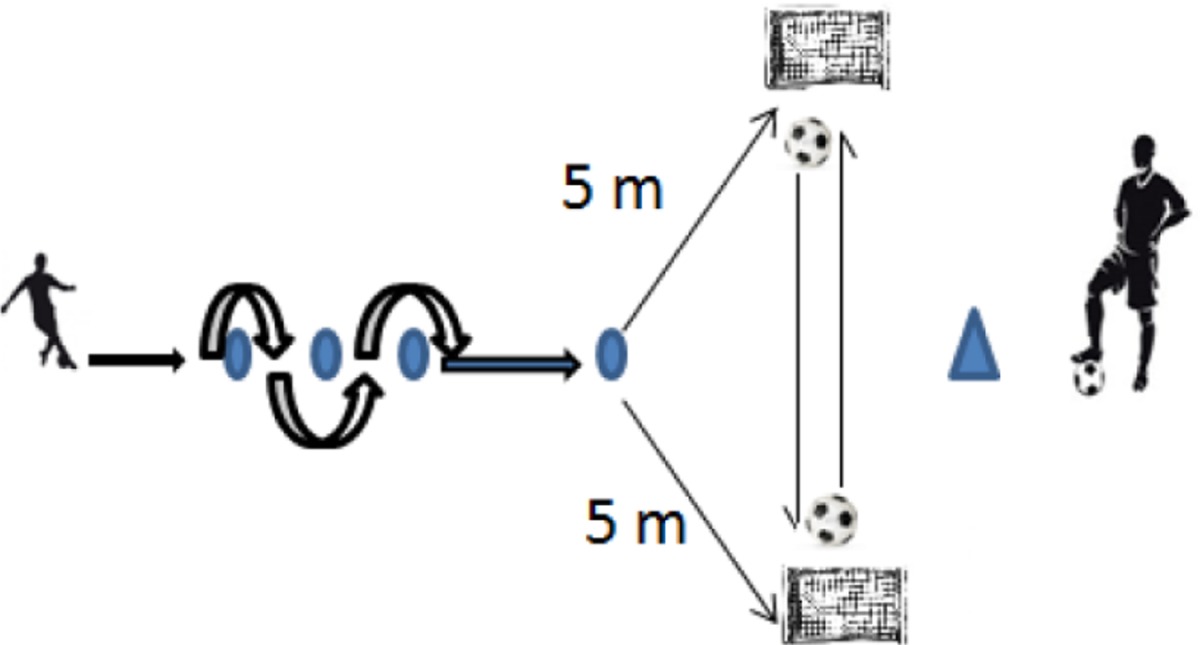

| Exercise 4 (COD and agility training): Drill performed with the ball. Same starting procedure as exercise 1. The player rapidly goes through the 3-m slalom. When out of the slalom he passes the ball to the coach. When the ball is smoothly shot from the coach towards one of the right or left small cages, the player accelerates to reach the ball before it enters the cage, blocks the ball and then changes direction towards the opposite cage and when approaching it, shoots the ball into the net. |  |

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Before using parametric tests, the assumption of normality was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk W-test. The data were then analysed using multivariate analysis of variance (3x2) with repeated measures. The factors included three separate training groups (COD-G, AG-G and CON-G) and repeated measures of time (pre- and post-training). Because of the slight differences in the initial groups, analysis of covariance with the pre-test values as the covariate was used to determine significant differences between the post-test adjusted means in the groups. If significant main effects were present, Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was performed. The effect size was calculated for all ANCOVAs using partial eta-squared. The values of 0.01, 0.06 and 0.15 were considered as small, medium and large cut-off points, respectively [28]. Effect size (ES) was also calculated for all paired comparisons and evaluated with the method described by Cohen [28] (small < 0.50, moderate = 0.50–0.80 and large > 0.80). Test/re-test reliability was assessed with Cronbach’s model intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), standard error of measurements (SEM) and coefficient of variation (CV) according to the method of Hopkins [29]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version. 16.0), and significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

No significant pre-to-post training variations in anthropometric variables were found in the studied groups. The ICC and SEM values for all measures demonstrated high reliability (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Test-retest reliability of tests.

| Criterion measures | ICC3,1 [95% CI] | SEM | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15m-SS (s) | 0.974 [0.945-0.987] | 0.004 | 1.12 |

| 15m-AR (s) | 0.936 [0.862-0.970] | 0.015 | 1.22 |

| 15m-AR-B (s) | 0.877 [0.741-0.942] | 0.047 | 2.06 |

| 5-0-5 agility test (s) | 0.945 [0.885-0.974] | 0.016 | 1.89 |

| RAT (s) | 0.867 [0.580-0.947] | 0.018 | 1.99 |

| RAT-B (s) | 0.861 [0.711-0.934] | 0.027 | 2.03 |

Note: ICC = interclass correlation coefficient, SEM = standard error of measurement, CV= coefficient of variation, SS = straight sprint

Linear sprinting test

The covariance analysis for the 15m-SS indicated significant differences between groups (F=5.02; p<0.001; η2=large). Post-hoc analysis indicated that at post-training both COD-G and AG-G improved significantly (2.21; ES=0.57 and 2.18%; ES=0.89 respectively) more than CON-G (0.59%; ES=0.14) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effect of 6 weeks of training on test performance (mean ± SD).

| Groups | Pre-test | Post-test | Change (%) | Cohen d | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p* | p† | ||||||

| 15m-SS (s) | COD AG CON |

2.25±0.09 2.25±0.05 2.30±0.10 |

2.20±0.07 c 2.20±0.07 c 2.28±0.09 |

-2.21±2.20 -2.18±1.70 -0.59±0.90 |

0.57 0.89 0.14 |

0.012 0.003 0.055 |

0.014 |

| 15m-AR (s) | COD AG CON |

3.47±0.17 3.52±0.12 3.48±0.06 |

3.28±0.12 b, c 3.39±0.13 c 3.42±0.08 |

-5.41±2.13 -3.65±0.85 -1.62±0.93 |

1.15 1.05 0.96 |

0.000 0.000 0.000 |

0.000 |

| 15m-AR-B (s) | COD AG CON |

4.48±0.17 4.45±0.27 4.55±0.21 |

4.19±0.20 c 4.16±0.17 c 4.40±0.17 |

-6.37±2.65 -6.39±2.80 -3.23±1.60 |

1.66 1.07 0.71 |

0.000 0.000 0.000 |

0.001 |

| 5-0-5 agility test (s) | COD AG CON |

2.42±0.15 2.49±0.17 2.52±0.14 |

2.34±0.11 b, c 2.43±0.11 c 2.49±0.09 |

-3.41±1.82 -2.24±2.59 -0.97±3.24 |

0.55 0.35 0.19 |

0.000 0.024 0.296 |

0.000 |

| RAT (s) | COD AG CON |

2.09±0.09 2.15±0.09 2.12±0.08 |

1.99±0.08 c 1.94±0.08 a, c 2.09±0.09 |

-4.59±3.43 -9.37±3.93 -1.48±1.29 |

1.09 2.28 0.40 |

0.002 0.000 0.005 |

0.000 |

| RAT-B (s) | COD AG CON |

2.51±0.12 2.56±0.07 2.57±0.16 |

2.38±0.11 2.36±0.04 a, c 2.46±0.13 |

-5.00±1.26 -7.73±2.66 -4.28±1.98 |

1.03 2.99 0.71 |

0.000 0.000 0.000 |

0.000 |

Note: *Significant difference from pre-test to post-test (p < 0.05).

Significant difference between groups after training (p < 0.05).

Significantly different from COD

Significantly different from AG

Significantly different from CON (p < 0.05)

COD = change of direction group; AG= agility group; CON = control group; SS = straight sprint; AR = agility run; s = seconds.

Change of direction tests

A significant group effect was observed for the 15m-AR (F=18.45; p<0.001; η2=large), 5-0-5 agility test (F=15.96; p<0.001; η2=large), and 15m-AR-B (F=9.61; p<0.001; η2=large). In the 15m-AR and 5-0-5 agility test, COD-G improved significantly more (5.41%; ES=1.15 and 3.41; ES=0.55 respectively) than AG-G (3.65%; ES=1.05 and 2.24; ES=0.35 respectively) and control-G (1.62%; ES=0.96 and 0.97; ES=0.19 respectively). Furthermore, AG-G improved in the 15m-AR and 5-0-5 agility test significantly more than CON-G (p<0.05). In 15m-AB, COD and AG groups were similar, and showed significantly greater post-intervention improvements (6.37%, ES=1.66 and 6.39%; ES=1.07 respectively) than CON-G (3.23%; ES=0.71) (Table 3).

Reactive agility tests

A significant group effect was observed for the RAT (F=15.86; p<0.001; η2=large) and RAT-B (F=10.35; p<0.001; η2=large). Improvements in RAT and RAT-B were higher (9.37%; ES=2.28 and 7.73%; ES=2.99 respectively) in AG-G than other groups (Table 3). Furthermore, COD-G increased more in RAT than CON-G (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to examine the effects of AG training compared with COD training on the performance of linear sprinting, COD, and AG tests in young elite soccer players. The results revealed that AG-G showed significantly greater improvements in RAT and RAT-B compared with COD-G and CON-G, whereas COD-G showed significantly greater improvements in the 15m-AR and 5-0- 5 agility test compared with AG-G and CON-G. Nevertheless, no significant differences were found in 15m SS and 15m-AR-B improvements between COD-G and AG-G. The originality of this study was the inclusion of generic AG training exercises with and without a ball, which mimics COD actions performed during soccer games. Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first study comparing COD and AG testing and training amongst the same population of young elite soccer players.

The major findings of the current investigation highlight that AG or COD training programmes induce an improvement of sprinting performance in young elite soccer players. Indeed, COD-G and AG-G improved significantly in the 15m SS performance (the improvement ranged from 2.18% to 10.23%). Data from the present study were in line with previous studies [15, 23] reporting a significant improvement in straight sprint time performance following AG/COD training, indicating a possible training transfer between these physical qualities [23, 30]. The improvement in sprinting performance after AG and COD training could be partly explained by the improvement in leg extensor power and the ability to produce lower limb force more efficiently after training, as previously reported [31, 32]. Nevertheless, the lack of strength measurements could be considered as a limitation of the present study. In fact, according to Lockie et al. [33], strength and power required for COD and linear sprinting are similar (and fit the model proposed by Young et al. [4]). Moreover, the nature of the AG and COD training exercises (i.e. straight sprint followed by a COD) may explain the improvement in sprinting ability, since participants consistently performed these exercise skills during six weeks.

The results demonstrated that COD-G and AG-G improved in COD tests (with and without a ball) better than CON-G. Moreover, as expected, COD-G had the greatest improvement in 15m-AR and 5-0-5m agility tests when compared to AG-G and CON-G. It is well known that agility is influenced by several factors such as linear sprinting and strength [3]. The COD training performed in the present study included specific exercises that improve these factors. In that regard, significant improvement in COD performance following 16 weeks of specific COD exercises was reported [13]. Furthermore, Milanovic et al. [16] concluded that COD training allowed improvement in COD tests (with and without a ball) among young soccer players. However, the performance improvement observed after COD training may also be related to an increase of lower limb strength. Indeed, it has been reported that COD training increased strength and power of leg extensors, which improved re-acceleration ability during the re-acceleration phase of the change of direction. Moreover, it can be speculated that COD training also allows athletes to improve the COD technique and therefore improve the efficiency of their cuts.

The data also showed that 6 weeks of AG and COD training programmes significantly improved AG performance with and without a ball. Nevertheless, the AG training allowed better improvement in RAT and RAT-B when compared to the COD training group. Therefore, agility training could be recommended for improving agility performance and enhancing related soccer performance. The results of the present investigation were expected and were in accordance with previous studies [23, 24]. In that context, Chaouachi et al. [23] reported a significantly greater improvement in the AG-group when they compared the effect of 6 weeks of COD vs SSG training on AG tests. Additionally, it has been reported that 3 weeks of specific AG training (reacting to a video by changing direction) allowed significant improvement in total AG time and also perception and response time [24]. However, the implications of cognitive factors (decision making) are crucial to interpret improvements in AG tests. Indeed, it has been previously reported that decision time is highly correlated with agility despite the fact that the decision time represents only 3.6% of the total agility test time [24]. Accordingly, decision-making ability should be considered as a determinant factor of agility performance. Indeed, as previously demonstrated, compared to sub-elite players, elite players are able to use appropriate postural cues (i.e. hip flexion, position of the leg/centre of mass) which serve as a visual stimulus to make their decisions about opponents’ actions [34–36]. Previous studies also reported that AG training improved the ability to perceive relevant information about opponents’ movements and react quickly and accurately [18, 24]. We believe that the study design used exercises with high ecological validity. Indeed, the signal given to the players to change direction in their reactive agility drills was given by a movement of a person managing/ moving a ball. This is considered as closer to the reality of soccer than a whistle sound signal for instance. Further studies should experiment with the effects of using field-based training compared to video-based training. In this context, Young and Rogers [18] demonstrated a significant improvement (31%) in decision making time following 11 sessions of SSGs in Australian football players [37]. The authors of the latter investigation concluded that cognitive skills could be enhanced via specific agility training. Consequently, the better performance on agility tests (with and without a ball) following RAT of the present study may be due to an improvement in decision time (cognitive factors). However, response accuracy, reaction and/ or decision time were not assessed in the present investigation. Consequently, future studies assessing these parameters are warranted.

One of the limitations of the present investigation was that it did not take into consideration the effect of laterality of players. In that regard, it has been reported that young elite soccer players had a better COD performance with the dominant leg vs. the non-dominant leg [2]. Therefore, the difference in time performance between groups in the present study may be influenced by players’ laterality. For this reason, future studies should take into consideration the effect of laterality when comparing different training groups. It has to be noted that COD ability is not relevant to soccer performance, even though some coaches use COD training and testing. The reactive agility training and testing are more relevant to soccer play because players almost never perform COD movements without a stimulus.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study showed that agility and change of direction training allowed a significant improvement in linear sprinting ability in young elite soccer players. It appears that including specific agility drills provides greater benefits to athletic and cognitive performances when compared to change of direction training. Consequently, it is suggested for coaches and physical trainers to routinely incorporate exercises that require reacting to a “specific stimulus” in agility training sessions.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chamari K, Hachana Y, Ahmed YB, Galy O, Sghaier F, Chatard JC, et al. Field and laboratory testing in young elite soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(2):191–196. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2002.004374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouissi M, Chtara M, Owen A, Chaalali A, Chaouachi A, Gabbett T, et al. Effect of leg dominance on change of direction ability amongst young elite soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(6):542–548. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1129432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheppard JM, Young WB. Agility literature review: classifications, training and testing. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(9):919–932. doi: 10.1080/02640410500457109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young WB, Dawson B, Henry GJ. Agility and Change-of-Direction Speed are Independent Skills: Implications for Training for Agility in Invasion Sports. International journal of Sports Science & Coaching. 2015;10(1):159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenmann JC, Malina RM. Age- and sex-associated variation in neuromuscular capacities of adolescent distance runners. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(7):551–557. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000101845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonson A, Ratel S, Le Fur Y, Cozzone P, Bendahan D. Effect of maturation on the relationship between muscle size and force production. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(5):918–925. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181641bed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markovic G, Jukic I, Milanovic D, Metikos D. Effects of sprint and plyometric training on muscle function and athletic performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21(2):543–549. doi: 10.1519/R-19535.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polman R, Walsh D, Bloomfield J, Nesti M. Effective conditioning of female soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2004;22(2):191–203. doi: 10.1080/02640410310001641458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young, McDowell MH, Scarlett BJ. Specificity of sprint and agility training methods. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(3):315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockie R, Schultz A, Callaghan S, Jordan C, Luczo T, Jeffriess M. A preliminary investigation into the relationship between functional movement screen scores and athletic physical performance in female team sport athletes. Biol Sport. 2015;32(1):41–51. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1127281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez-Campillo R, Burgos CH, Henriquez-Olguin C, Andrade DC, Martinez C, Alvarez C, et al. Effect of unilateral, bilateral, and combined plyometric training on explosive and endurance performance of young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(5):1317–1328. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shalfawi SA, Haugen T, Jakobsen TA, Enoksen E, Tonnessen E. The effect of combined resisted agility and repeated sprint training vs. Strength training on female elite soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(11):2966–2972. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828c2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christou M, Smilios I, Sotiropoulos K, Volaklis K, Pilianidis T, Tokmakidis SP. Effects of resistance training on the physical capacities of adolescent soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(4):783–791. doi: 10.1519/R-17254.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cressey EM, West CA, Tiberio DP, Kraemer WJ, Maresh CM. The effects of ten weeks of lower-body unstable surface training on markers of athletic performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21(2):561–567. doi: 10.1519/R-19845.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockie RG, Jeffriess MD, McGann TS, Callaghan SJ, Schultz AB. Planned and Reactive Agility Performance in Semi-Professional and Amateur Basketball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2013 doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milanovic Z, Sporis G, Trajkovic N, James N, Samija K. Effects of a 12 Week SAQ Training Programme on Agility with and without the Ball among Young Soccer Players. J Sports Sci Med. 2013;12(1):97–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trajkovic N, Milanovic Z, Sporis G, Milic V, Stankovic R. The effects of 6 weeks of preseason skill-based conditioning on physical performance in male volleyball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(6):1475–1480. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318231a704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young W, Rogers N. Effects of small-sided game and change-of-direction training on reactive agility and change-of-direction speed. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(4):307–14. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.823230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabbett TJ. Performance changes following a field conditioning program in junior and senior rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(1):215–221. doi: 10.1519/R-16554.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lockie RG, Schultz AB, Callaghan SJ, Jeffriess MD. The Relationship between Dynamic Stability and Multidirectional Speed. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a744b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macura MM, Gabbett T, Baechle T. Il faut mettre le nom complet de l’article le nom complet du journal. 2011;24(12):126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabbett TJ. Skill-based conditioning games as an alternative to traditional conditioning for rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(2):309–315. doi: 10.1519/R-17655.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaouachi A, Chtara M, Hammami R, Chtara H, Turki O, Castagna C. Multidirectional sprints and small-sided games training effect on agility and change of direction abilities in youth soccer. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(11):3121–3127. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serpell BG, Young WB, Ford M. Are the perceptual and decision-making components of agility trainable? A preliminary investigation. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(5):1240–1248. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d682e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Draper JA, Lancaster MG. The 505 test for agility in the horizontal plane. J Sci Med Sport. 1985;17:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mujika I, Santisteban J, Impellizzeri FM, Castagna C. Fitness determinants of success in men’s and women’s football. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(2):107–114. doi: 10.1080/02640410802428071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young WB, Willey B. Analysis of a reactive agility field test. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(3):376–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillside, NJ: L Erbraum Associates; 1988. pp. 23–97. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopkins WG. A scale of magnitudes for effect statistics. 2009. Available at: http://wwwsportsciorg/resource/stats/indexhtml.

- 30.Sporiš G, Milanović L, Jukić I, Omrčen D, Molinuevo JS. The Effect of Agility Training on Athletic Power Performance. Kinesiology. 2010;42(1):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker D. A comparison of running speed and quickness between elite professional and young rugby league players. Strength and Conditioning Coach. 1999;7(3):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayers M. Running techniques for field sport players. Sports Coach, Autumn. 2000:26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockie RG, Schultz AB, Callaghan SJ, Jeffriess MD. The Effects of Traditional and Enforced Stopping Speed and Agility Training on Multidirectional Speed and Athletic Performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabbett TJ, Kelly JN, Sheppard JM. Speed, change of direction speed, and reactive agility of rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(1):174–181. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31815ef700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henry G, Dawson B, Lay B, Young W. Validity of a reactive agility test for Australian football. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6(4):534–545. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henry GJ, Dawson B, Lay BS, Young WB. Relationships between reactive agility movement time and unilateral vertical, horizontal and lateral jumps. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a20ebc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nimmerichter A, Weber JR, Wirth K, Haller A. Effects of Video-Based Visual Training on Decision-Making and Reactive Agility in Adolescent Football Players. Paediatric Exercise Physiology. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.3390/sports4010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]