Abstract

This study was designed to assess the effect of strength and power training on throwing velocity and muscle strength in handball players according to their playing positions. Twenty-two male handball players were assigned to either an experimental group (n=11) or a control group (n=11) (age: 22.1 ± 3.0 years). They were asked to complete (i) the ball throwing velocity test and (ii) the one-repetition maximum (1-RM) tests for the half-back squat, the pull-over, the bench press, the developed neck, and the print exercises before and after 12 weeks of maximal power training. The training was designed to improve strength and power with an intensity of 85-95% of the 1RM. In addition to their usual routine handball training sessions, participants performed two sessions per week. During each session, they performed 3-5 sets of 3-8 repetitions with 3 min of rest in between. Then, they performed specific shots (i.e., 12 to 40). Ball-throwing velocity (p<0.001) was higher after the training period in rear line players (RL). The training programme resulted in an improvement of 1RM bench press (p<0.001), 1RM developed neck (p<0.001) and 1RM print (p<0.001) in both front line (FL) and RL. The control group showed a significant improvement only in ball-throwing velocity (p<0.01) and 1RM bench press (p<0.01) in RL. A significantly greater improvement was found in ball-throwing velocity (p<0.001), 1RM bench press (p<0.001), and 1RM half-back squat exercises in players of the central axis (CA) compared to the lateral axis (LA) (p<0.01). The power training programme induced significantly greater increases in ball-throwing velocity and muscle strength in FL than RL and in CA than LA axis players.

Keywords: Handball, Power training, Axis and line, Throwing velocity

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, handball performances depend on the technical, tactical, and physical qualities of the players. The intensity of the game is considerably changed and players seem to sprint faster, jump higher, pull harder and run longer [1]. In addition, successful players seem to be taller, with higher fat-free mass and anaerobic power [2, 3, 4]. Recent studies noted that handball players performed different tasks with different physical demands, depending on their playing position [5]. In response to different offensive and defensive situations, players have to develop endurance and short-term explosive capacities such as jumping, fainting, blocking, sprinting and throwing [6]. However, the percentage of success for scoring, in a large part, upon the velocity of the ball and the accuracy of the throw [7, 8, 9]. In this context, in addition to technical and tactical skills, it has been argued that two of the key skills necessary for success in team handball are muscle strength and power [10]. Thus, the exploration of the relationship between explosive strength during the ball-throwing test and ball velocity is of paramount importance in sports involving throwing movements such as handball. These characteristics are considered as important aspects of the game that contribute to the high performance of the team [7, 8].

The analysis of handball matches has shown that the quality of the developed efforts differed significantly between players regarding their playing positions [9, 11, 12]. In a previous study, [2] handball players were classified as goalkeepers, wings and pivots. Nevertheless, the differences in physical performance between offensive and defensive actions according to axes and lines have still not been considered by scientists. The evaluation of physical performance according to the players’ positions would be useful for coaches to follow the most specific training regimes. In this context, the question remains whether coaches should organize physical training in groups based on six positions (i.e., left wing, left back, middle back, right back, right wing, and line) or they should separate the axis and lines players. We hypothesized that coaches should separate the axis and lines players during the training sessions. In addition, to improve physical performance coaches must consider how to develop the strength and power of each player during the training sessions (i.e., individualization of the training programme).

In this context, Gorostiaga et al. [13] showed significant enhancement of standing handball throwing velocity after 6 weeks of heavy upper limb resistance training; however, they utilized few exercises in their study (i.e., supine bench press, half squat, knee flexion curl, leg press and pec-dec). Therefore, the purposes of the present study were: (i) to examine the effect of combined strength-power training on athletic performance in handball players, and (ii) to determine the difference in strength and power according to players’ positions (i.e., line and axis playing positions (front (FL) and rear lines (RL), central (CA) and lateral (LA) axes).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twenty-two elite male handball players (recruited from a team ranked among the better of the Tunisian first league) having 12 years of training experience (age: 22.1±3.0 years, body mass: 82.74±12.2 kg, height: 181.1±4.7 cm: body mass index: 24.89±3.2 kg · m-2) volunteered to participate in this study. The study was conducted in the first part of the season from September to November, after the preparation phase. All players performed seven training sessions of handball per week and participated regularly in one match per week in the first league of the Tunisian handball championship teams. After receiving a description of the protocol, and having been made aware of the possible risks and benefits associated with the study, each subject signed a written informed consent form prior to participation. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was fully approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Centre of Medicine and Science of Sports of Tunis (CNMSS) before the commencement of the assessments.

Players were assigned to either an experimental group (n=11) [FL (n = 5), RL (n = 6), CA (n=3), and LA (n = 8)] or a control group [(n=11) FL (n = 5), RL (n = 6), CA (n=4) LA (n = 7)]. Players of the experimental group continued to train the routine handball sessions and performed an additional strength training programme. However, players of the control group performed only the handball sessions. The club has accepted that the players of the experimental group performed the additional strength training and the players of the control group performed only the handball sessions. The goalkeepers were not included in this study.

Testing schedule

The subjects were habituated with the testing protocol as they performed these exercises as part of their regular training routine. They were assessed on the same day, and the tests were performed in the same order at 11:00 a.m. Testing was conducted over three sessions separated by at least two days to allow adequate recovery from any acute effects of their training. On the first test day, the biometric assessment was performed followed by the 1-RM half-back squat test. On the second day, 1-RM pull over, 1-RM bench press, 1-RM developed neck and 1-RM print were assessed. The 1-RM was measured according to the standardized procedures. Before each test session the subjects performed 15 min of warm-up. The formula used is: weight / (1.0278-(0.0278 × reps) [11].

All participants used an initial weight for each exercise, which was subsequently increased in increments of 10 or 5 kg for each trial until an individual could not execute a successful lift. Subjects performed a single repetition at each absolute load [11]. The 1-RM showed an ICC of 0.91 (95% interval 0.62–0.98) and a CV of 9.7% [11].

On the third day, the ball throwing velocity was determined. All tests were performed before and after the 12 weeks of training.

Ball throwing velocity

After a 10 min standardized warm-up, the subjects were instructed to throw a standard handball (i.e., mass 475 g, circumference 58 cm, 0.4 atm1, IHF size 3 for men) with maximal velocity at a standard goal, using their preferred throwing arm and throwing technique. Players were allowed only a 3-step preparatory run and were required to release a jump shot of the ball behind the area of 9 m. Each subject executed 5 throws, with 2 min of rest between trials. The average of the 4 greatest velocity throws was used for analysis. [10] Different shootings were recorded using 5 digital camcorders (SONY, DCL, and TRV 130E) fixed on the stadium centre, and at 4 angles. The software “STUDIO 9” was used for cutting the pictures shot. Speed of the ball at the different shootings was calculated by REGAVI software, version 2.57, 2004. This software is an external module of Regression intended to extract the information of BMP files, JPEG, WAV, AVI, MPEG or MOV and to send it to Regression [12].

Training programme

Throughout the study, the experimental group trained twice per week over a period of 12 weeks (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The training programme followed by the experimental group over 12 consecutive weeks.

| Week | Sessions 1 | Session 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % 1RM | sets | Repetitions | Rest | shoots | % 1RM | sets | repetitions | Rest | shoots | |

| 1-2 | 90 | 4 | 6 | 3min. | 12 | 85 | 5 | 8 | 3 min. | 18 |

| 3-4 | 90 | 4 | 8 | 3 min. | 18 | 85 | 5 | 8 | 3 min. | 20 |

| 5-6 | 95 | 3 | 4 | 3 min. | 20 | 90 | 4 | 6 | 3 min. | 22 |

| 7-8 | 95 | 3 | 3 | 3 min. | 24 | 90 | 3 | 4 | 3 min. | 24 |

| 9-10 | 85 | 4 | 4 | 3 min. | 30 | 85 | 4 | 6 | 3 min. | 30 |

| 11-12 | 95 | 3 | 3 | 3 min. | 36 | 90 | 3 | 4 | 3 min. | 40 |

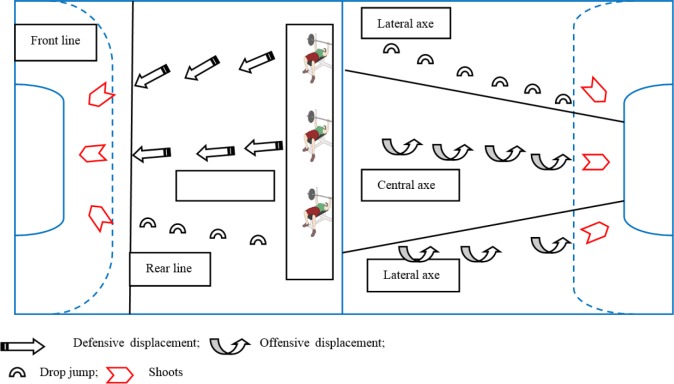

Training interventions were performed on-court, separated by at least 48 hours. Biweekly sessions were held on Tuesdays and Thursdays, immediately before normal handball training. They consisted of combined strength and power training (i.e., intensity: 85% to 95% of the 1RM; sets: 3 to 5; repetitions: 3 to 8; recovery between sets: 3 min) concluded with specific shots (12 to 40) twice per week. The training exercises were: half-back squat, pull over, bench press, developed neck, print and specific shots training according to axis and lines playing position (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Strength training exercises concluded with specific shots according to playing positions.

The control group was engaged in the usual training programme (i.e., 7 handball training session per week) and one official match game per week.

Statistical analyses

Since data distribution normality was confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk W-test, the data were analyzed using a 3-way analysis of variance with repeated measures (2 [group] × 2 [position] × 2 [training]). When appropriate, significant differences among means were tested using the Tukey post hoc test. The data are expressed as mean ± SD in the text and in the tables. Effect sizes were calculated as partial eta-squared to estimate the meaningfulness of significant findings. A probability level of 0.05 was selected as the criterion for statistical significance.

RESULTS

In the experimental group, significant increases in ball-throwing velocity were observed in both playing positions, with greater improvement in FL (25.76%; = 0.8; p<0.001) than RL (16.91%; = 0.7; p<0.001). 1-RM bench press performance increased in both lines, with greater improvement in RL (23.27%; = 0.8; p<0.001) than FL (18.51%; = 0.7; P<0.001). 1-RM developed neck and 1-RM print were greater in FL (18.51% and 16.45% respectively; p<0.001) than RL (14.11% and 11.41% respectively; = 0.6; P<0.001). Likewise, 1-RM pull over increased significantly in both FL and RL (P<0.01). However, the training programme induced significant increases in 1RM half back- squat only in FL.

Ball-throwing velocity increased greatly in CA (26.63%) than LA (18.80%) (Table 2). Likewise, 1RM half back-squat and 1RM bench press were higher in CA (15.46% and 29.63% respectively) than LA (11.99% and 20.10% respectively). However, 1RM developed neck was lower in CA (15.85%; = 0.6; P<0.01) compared to LA (16.21%). Likewise, 1RM pull over increased more in LA (12.87%) compared to CA (9.2%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of additional training programme in strength and power on the force-velocity performances among elite handball players according to axis playing positions.

| Central axe | % | Lateral axe | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | ||||

| Experimental group | ball-throwing velocity (m · s-1) | 21.6 ± 3.9 | 26.9 ± 2.0† | 26.63 | 22.91± 1.7 | 27.1 ± 1.2† | 18.8 |

| 1RM half-back squat (kg) | 297.3 ± 7.1¥ | 343.3 ± 11.5†¥ | 15.46 | 261.2 ± 26.6 | 292.5 ± 33.7† | 11.99 | |

| 1RM bench press (kg) | 100.0 ± 17.3 | 128.6 ± 12.5†¥ | 29.63 | 105.6 ± 4.9 | 126.6 ± 6.9†¥ | 20.1 | |

| 1RM developed neck (kg) | 67.0 ± 9.6¥ | 77.3 ± 8.9†¥ | 15.85 | 71.6 ± 3.1¥ | 83.2 ± 4.9†¥ | 16.21 | |

| 1RM print (kg) | 73.0 ± 8.18 | 81 .0 ± 9.6† | 10.96 | 75 .0± 4.4 | 86.0 ± 4.9† | 14.75 | |

| 1RM pull-over (kg) | 74.7 ± 9.6 | 81.3 ± 8.1 | 9.2 | 69.0 ± 5.2 | 78.7 ± 5.9† | 12.87 | |

| Control group | ball-throwing(m · s-1) | 22.7 ± 2.4 | 25.2 ± 3.5† | 10.99 | 23.4 ± 2.0 | 25.4 ± 2.3† | 8.71 |

| 1RM half-back squat (kg) | 225.0 ± 25.1 | 239.0 ± 28.8 | 6.4 | 224.0 ± 15.6 | 239.0 ± 19.3 | 6.23 | |

| 1RM bench press (kg) | 95.0 ± 5.8 | 107.5 ± 8.6† | 13.19 | 104.0 ± 8.4 | 113.0 ± 8.5†¥ | 8.95 | |

| 1RM developed neck (kg) | 58.2 ± 2.4 | 63.5 ± 2.5 | 9 .05 | 59.7 ± 4.2 | 62.8 ± 4.6 | 5.29 | |

| 1RM print (kg) | 70.0 ± 3.3 | 73.0 ± 2.6¥ | 4.33 | 69.1 ± 3.4¥ | 72.8 ± 3.4¥ | 5.41 | |

| 1RM pull-over (kg) | 65.0 ± 2 | 67.5 ± 4.4 | 3.77 | 62.6 ± 3.6 | 65.1 ± 3.0¥ | 4.17 | |

Note: 1-RM = one repetition maximum; Values are given as mean ± SD;

differ significantly between T1 and T2;

Significant difference between experimental and control group

The control group did not show any significant changes in 1-RM half-back squat, developed neck print and pull over, for both front and rear lines. The ball throwing velocity and 1-RM bench press increased only in the RL (13.4%; = 0.6; p < 0.01) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effects of additional training programme in strength and power on the force-velocity performances among elite handball players according to line playing positions.

| Front line | % | Rear line | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | ||||

| Experimental group | ball-throwing velocity (m · s-1) | 21.7 ± 2.7 | 27.1 ± 1.1†¥ | 25.8 | 22.9 ± 1.7 | 27.1 ± 1.2† | 18.8 |

| 1RM half-back squat (kg) | 268.3 ± 19.8¥ | 316.3 ± 28.8† | 17.5 | 261.2 ± 26.6 | 292.5 ± 33.7† | 11.99 | |

| 1RM bench press (kg) | 109.0 ± 17.3 | 132.0 ± 12.5†ψ | 18.5 | 105.6 ± 4.9 | 126.6 ± 6.9†¥ | 20.1 | |

| 1RM developed neck (kg) | 70.6 ± 5.1¥ | 83.6 ± 5.7† | 18.5 | 71.6 ± 3.1¥ | 83.2 ± 4.9†¥ | 16.21 | |

| 1RM print (kg) | 74.5 ± 5.5 | 86.6 ± 5.5†¥ | 16.5 | 75 ± 4.37 | 86 ± 4.89† | 14.75 | |

| 1RM pull-over (kg) | 68.4 ± 5.9 | 76.4 ± 5.5† | 11.8 | 69.0 ± 5.2 | 78.7 ± 5.9† | 12.87 | |

| Control group | ball-throwing(m · s-1) | 23.1 ± 2.6 | 24.2 ± 3.2¥ | 5.2 | 23.4 ± 2.0 | 25.4 ± 2.3† | 8.71 |

| 1RM half-back squat (kg) | 222.0 ± 19.2 | 236.6 ± 17.9 | 6.7 | 224 ± 15.6 | 239 ± 19.3 | 6.23 | |

| 1RM bench press (kg) | 101.0 ± 2.2 | 111.0 ± 5.5¥ | 9.9 | 104.0 ± 8.4 | 113.0 ± 8.5†¥ | 8.95 | |

| 1RM developed neck (kg) | 59.2 ± 5.0 | 63.0 ± 5.7 | 6.5 | 59.7 ± 4.2 | 62.8 ^ ± 4.6 | 5.29 | |

| 1RM print (kg) | 68.8 ± 3.9 | 72.4 ± 3.8 | 5.3 | 69.1 ± 3.4¥ | 72.8 ± 3.4¥ | 5.41 | |

| 1RM pull-over (kg) | 65.2 ± 2.7 | 67.6 ± 4.3¥ | 3.6 | 62.6 ^ ± 3.6 | 65.1 ^ ± 3.0¥ | 4.17 | |

Note: 1-RM = one repetition maximum; Values are given as mean ± SD;

differ significantly between T1 and T2;

significantly difference between lines;

Significantly difference between experimental and control group.

Ball-throwing velocity and 1-RM bench press also increased in the control group more in CA (10.99%) than LA (8.71%).

DISCUSSION

The present study results demonstrate that biweekly strength/power training associated with regular routine handball training enhances the ball-throwing velocity and the maximal power and strength of elite handball players. These observations could help coaches in scheduling some strength/power training in addition to the handball training. Indeed, one of the important technical-tactical elements and the key to winning the handball game is shots on goal. The effectiveness of these shots depends on the success of the preceding actions and affects possible victory. It is well known that a successful shot on goal in handball depends on throwing ability and ball velocity [14]. Although previous studies have demonstrated that velocity can impair accuracy, in elite players this inverse relationship is not significant [15].

Combined training is considered to be one of the important parts of the training programmes used by fitness coaches to develop both muscle strength and power [16]. In this context and in agreement with the present study findings, Coffey and Hawley [17] stated that this exercise mode positively influenced the training adaptations in skeletal muscle.

The present study results showed a significant improvement in muscle strength in both groups (i.e., the experimental and the control group) with greater increases in the FL than RL and CA than LA. This could be partially explained by specific training according to players’ positions and to the specific physical characteristics of each post. These results are in accordance with Gorostiaga et al. [18], who noted significant enhancement of standing handball throwing velocity after 6 weeks of heavy upper limb resistance training; however, the training exercises are different between the present study and the investigation of Gorostiaga et al. [13] (i.e., supine bench press, half squat, knee flexion curl, leg press and pec-dec in the study of Gorostiaga et al. [14]). In this context, previous studies showed significant differences between playing positions in some measures of physical fitness. For example, it was reported that countermovement jump was higher in goalkeepers compared to pivots, and higher in wings compared to backs, while in repeated sprint ability (i.e., 7 × 30 m), wings were the fastest, being significantly better than goalkeepers, alongside reports of better mean times in wings than in pivots and goalkeepers (GKs) [19].

The present study data indicate that a combination of resistance training with handball specific shots significantly enhanced maximal and specific-explosive strength of arms and legs and this improvement should give players an advantage in throwing, hitting, blocking, pushing, and holding [20].

The increased throwing velocity is likely of major importance to successful outcomes in handball. Indeed, elite handball players achieve substantially higher throwing velocities than lower level competitors (i.e., 8–9% advantage in men [20, 21] and 10–11% advantage in women [18]). A handball player must demonstrate a high level of explosive strength. The game includes numerous repetitive actions such as full speed running, changes in speed and direction, jumping, throwing, and collisions between players [11]. There are three determining factors critical to regulating the speed of ball release, the mechanics of the throw, the force development and the power in the upper and lower extremities [21]. To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing the effects of strength/power training adaptations in competitive male handball players according to axis and line playing positions. The results indicate that FL and RL and CA and LA showed different improvements in strength and ball throwing velocity. The increases recorded in ball-throwing velocity were greater in FL than RL. However, 1-RM bench press increases were higher in RL than FL. The 1-RM developed neck and 1-RM print were greater in FL than RL. These findings could be explained by differences in the demands of each playing position during a handball match. Indeed, there is a difference in the specific combined training according to the players’ position. In this context, wing players are often involved in rapid game transitions and jumps that require both agility and quickness. Wings play in the outer aisles of the playing field in the attack and frequently also in the defence phase [2]. In these areas, 6 m shots are more commonly performed than 9 m, and thus height does not play such an important role compared to backs, whose role requires the use of height in order to overcome the defence barrier [2].

The force developed in 1-RM half back- squat increased only in FL. 1-RM pull over increased both in FL and RL (Table 2). Likewise, the control group showed greater improvements in ball-throwing velocity and 1-RM bench press, in RL than FL.

Moreover, ball-throwing velocity, half-back squat and bench press improved to a greater in CA than LA. However, the results indicated a significant improvements of 1-RM developed neck, 1-RM print and 1-RM pull-over from before to after training, which was greater in LA than CA. Likewise, participants of the control group improved their ball-throwing velocity and 1-RM bench press in both CA and LA.

The first major findings in the present study were the greater increases in ball throwing velocity, 1-RM half-back squat, 1-RM developed lying and 1-RM print in FL than RL. This finding could be the result of the training programme, which has been reported to positively affect the maximum force in both wingers and pivots [12]. Moreover, this increase could be explained by the fact that these players are not familiar with this type of training.

The second major findings of the present study were the differences in performance between axis playing positions. In fact, the training protocol induced greater improvements in ball-throwing velocity and 1-RM half-back squat and bench press in the CA than LA. As indicated above, this could be partially explained by specific training according to players’ positions and to the specific physical characteristics of each post.

Players involved in the resistance training group showed greater improvements in all types of strength than the control group. The main reason for this improvement seems to be that the experimental group followed a training programme based on combined exercises (strength and shots), which may positively induce improvements in muscle strength and power. Moreover, in the present study, the development of the power of arms and legs is based on an integrated approach to resistance training exercises concluded by a sequence of specific technical actions such as shots, feints and vertical jumps (Figure 1).

Strength and power training is one of the most widely practised forms of physical activity, which is used to enhance athletic performance, increase musculo-skeletal health and alter body aesthetics. This type of activity produces marked increases in muscular strength which could be attributed to a range of neurological and morphological adaptations [21].

CONCLUSIONS

The combination of technical-tactical and strength training based on specific power training increases ball-throwing velocity and maximum power. There are different increases in throwing velocity corresponding to different lines and axis playing positions. Players achieve higher increases in ball throwing velocity in RL than FL, and in LA than CA. The strength/power training concluded with specific shots induced specific improvements in muscle strength and power according to playing position in handball players. Coaches and trainers can effectively use the same programme to develop more effective defensive and offensive strength and conditioning for players from FL and RL, CA and LA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all players, trainers, and staff of the “African Club” for their cooperation.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Póvoas SC, Seabra AF, Ascensão AA, Magalhães J, Soares JM, Rebelo AN. Physical and physiological demands of elite team handball. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(12):3365–75. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318248aeee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolaidis PT, Ingebrigtsen J. Physical and physiological characteristics of elite male handball players from teams with a different ranking. J Hum Kinet. 2013;38:115–124. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2013-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massuca L, Fragoso I. Study of Portuguese handball players of different playing status. A morphological and biosocial perspective. Biol Sport. 2011;28(1):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasan AAA, Rahaman JA, Cable NT, Reilly T. Anthropometric profile of elite male handball players in Asian. Biol Sport. 2007;24(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rannou F, Prioux J, Zouhal H, Gratas-Delamarche A, Delamarche P. Physiological profile of handball players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2001 Sep;41(3):349–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorostiaga EM, Izquierdo M, Iturralde P, Ruesta M, Ibanez J. Effects of heavy resistance training on maximal and explosive force production, endurance and serum hormones in adolescent handball players. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;80:485–493. doi: 10.1007/s004210050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marques MC, Gonzalez-Badillo JJ. In-season resistance training and detraining in professional team handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:563–571. doi: 10.1519/R-17365.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spores G, Vuleta D, Vuleta DJR, Milanović D. Fitness profiling in handball: physical and physiological characteristics of elite players. Coll Antropol. 2010;34(3):1009–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronglan LT, Raastad T, Børgesen A. Neuromuscular fatigue and recovery in elite female handball players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(4):267–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cambel K. An assessment of the movement requirements of elite teamhandball athletes. Sports Med. 1985;3:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marques MC, Tillaar RVD, Vescovi JD, González-Badillo JJ. Relationship between Throwing Velocity, Muscle Power, and Bar Velocity During Bench Press in Elite Handball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2007;2:414–422. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2.4.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherif M, Gomri D, Aouidet A, Said M. The Offensive Efficiency of the High-Level Handball Players of the Front and the Rear Lines. Asian J Sports Med. 2011 Dec;2(4):241–248. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorostiaga EM, Granados C, Ibanez J, Gonzalez-Badillo JJ, Izquierdo M. Effects of an entire season on physical fitness changes in elite male handball players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:357–366. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000184586.74398.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorostiaga EM, Granados C, Ibáñez J, Izquierdo M. Differences in physical fitness and throwing velocity among elite and amateur male handball players. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26:225–232. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Párraga J, Sánchez A, Oña A. Importance of the output speed of the ball and accuracy and efficacy parameters in the distance jump shot in handball. Apunts: Educación Física y Deportes. 2001;66:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherif M, Said M, Chaatani S, Nejlaoui O, Gomri D, Aouidet A. The Effect of a Combined High-Intensity Plyometric and Speed Training Program on the Running and Jumping Ability of Male Handball Players. Asian J Sports Med. 2012;3(1):21–8. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coffey VG, Hawley JA. The molecular bases of training adaptation. Sports Med. 2007;37(9):737–63. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermassi S, Chelly MS, Fathloun M, Shephard R. The effect of heavy- vs. Moderate-load training on the development of strength, power, and throwing ball velocity in male handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:2408–2418. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e58d7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michalsik LB, Aagaard P, Madsen K. Match performance and physiological capacity of male elite team handball players; EHF Scientific Conference, Science and analytical expertise in Handball; Vienna. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermassi S, Chelly MS, Tabka Z, Shephard RJ, Chamari K. Effects of 8-week in-season upper and lower limb heavy resistance training on the peak power, throwing velocity, and sprint performance of elite male handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(9):2424–33. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182030edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgomaster KA, Howarth KR, Phillips SM, Rakobowchuk M, MacDonald MJ, McGee SL, Gibala MJ. Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans. J Physiol. 2008;586:151–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]