1. Introduction

In the last three decades, the prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) has increased from 1.1% to about 7.5% in the urban population and from 2.1% to 3.7% in the rural population.1 Coronary artery disease tends to occur at a younger age in Indians with 50% of cardiovascular (CV) mortality occurring in individuals aged less than 50 years.2, 3

In a view of high prevalence of CAD in India there is a need for cardiologists’ even physicians’ to be updated on the recent developments in diagnosis and treatment. However, currently every clinician is inundated with numerous data (for which he/she may have not have sufficient time to go through). Herein clinical guidelines provide a quick solution for day-to-day problems and assist physicians, particularly cardiologists, in clinical decision-making by delineating a gamut of commonly acceptable modalities for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of stable CAD (SCAD). On the other hand guidelines by themselves may have several limitations; they are generally developed based on practice in West (which might be different in developing world), they are too many, and they may be difficult to understand by an average physician. In this context practice standards and management algorithms may offer better guidance to a practicing physician.

The current practice standard has defined practices that meet the needs of most patients in the Indian context. A modified GRADE system was used to derive quality of evidence as 1 (high-quality evidence from consistent results of well-performed randomised trials), 2 (moderate quality evidence from randomised trials), 3 (low-quality evidence from observational studies), or 4 (practice point). The strength of recommendations was categorised as either A (“RECOMMENDED”, strong recommendation) or B (“SUGGESTED”, weak recommendation).

2. Diagnosis

-

•

Patient's history and physical examination should be considered to identify all the symptoms and signs of CV disease, CV risk factors, and other cardiac aetiologies. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)4, 5

-

•

The basic first-line testing in patients with suspected SCAD includes standard laboratory biochemical testing (including haemoglobin, glycated haemoglobin [HbA1c], lipid profile, liver, renal and thyroid function tests), a resting ECG, resting echocardiography and, a chest X-ray. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

-

•

It is recommended to include assessment of resting heart rate in SCAD patients as a routine clinical practice. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)12, 13, 14

-

•

Exercise electrocardiogram testing, if possible, should be preferred in patients with a pre-test probability (based on character of symptom, age and sex) of 15–65% as it is more relevant to their activities than pharmacological testing. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)15, 16

-

•

In patients who cannot exercise to an adequate workload, pharmacological testing with adenosine-induced vasodilator perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography should be considered. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)6

-

•

An invasive coronary angiogram is indicated in significantly symptomatic patients and patients with high risk features on non-invasive testing. [Grade A, Evidence 4]

-

•

Certain specific types of angina (microvascular, vasospastic and silent angina) should be diagnosed by a combination of available diagnostic techniques and should be individualised. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)6

3. Lifestyle management and control of risk factors

-

•

It is recommended to stop all forms of tobacco (smoking and smokeless) for the prevention and control of cardiovascular risk. (Grade A, Evidence level 1)17, 18, 19, 20

-

•

Patients with previous acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), stable angina pectoris, or stable chronic heart failure should undergo moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic exercise training ≥3 times a week and 30 min per session. Sedentary patients should be strongly encouraged to start light-intensity exercise programmes after adequate exercise-related risk stratification. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)21

-

•

Weight reduction in overweight and obese people is recommended to have favourable effects on blood pressure and dyslipidaemia, which may lead to less CVD. (Grade A, Level 1). More precisely, it is recommended to attain BMI <22.9 kg/m2 and WC (Men: 90 cm; women: 80 cm) to minimise the cardiovascular risk. [Grade A, evidence 1]50, 58, 59, 60, 61

-

•

All the SCAD patients should be treated with statins to achieve optimal LDL-C goal <70 mg/dl. [Grade A, Evidence 2]27, 28, 29, 30

-

•

All the SCAD patients with hypertension should be recommended to attain systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure goal of 140/90 mmHg and in diabetes 140/85 mmHg with medical management. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36

-

•

HbA1c of <7.0% should be the objective while treating SCAD patients with diabetes. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)37, 38, 39

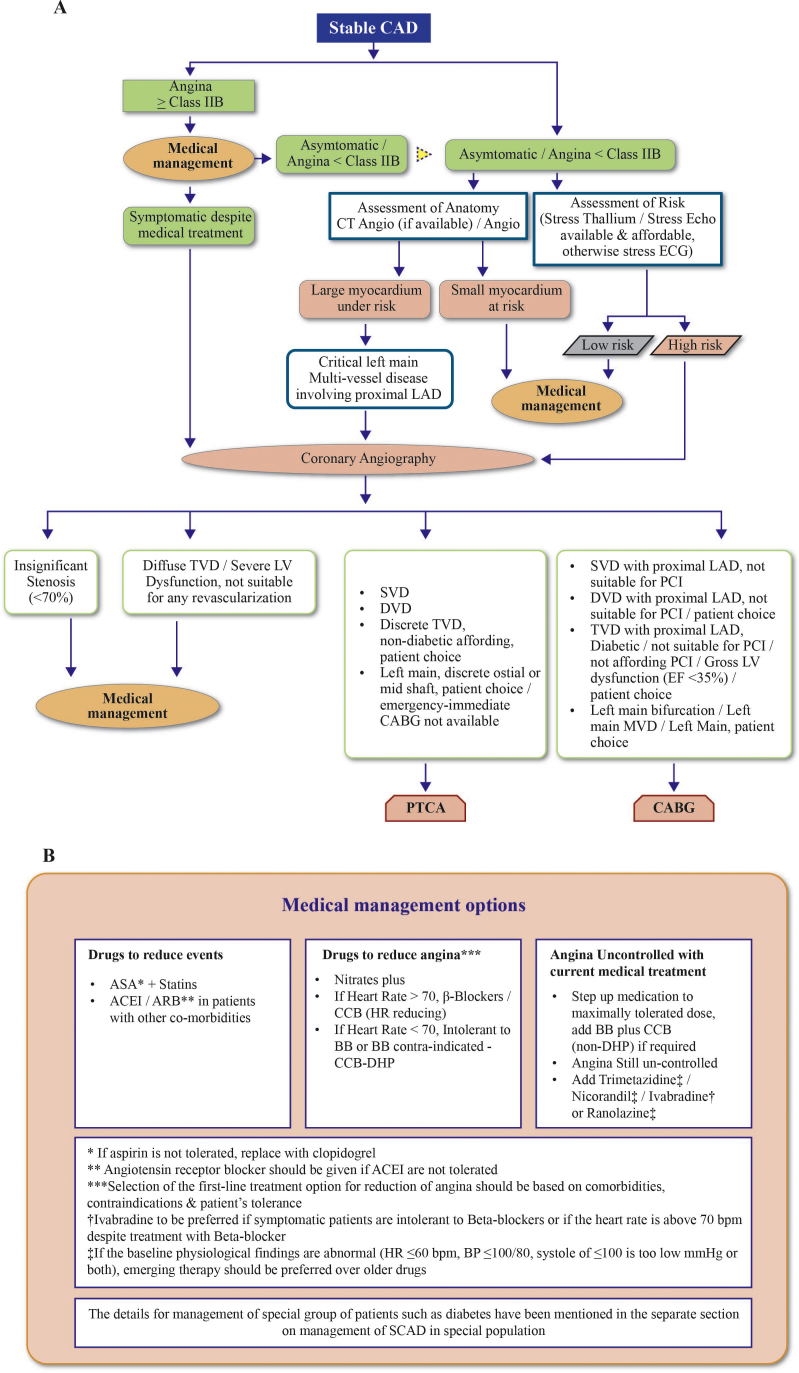

4. Pharmacological management (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

An algorithm for pharmacological management and event prevention. (A) Pharmacological management and event prevention. (B) Medical management options. Abbreviations: SCAD, stable coronary artery disease; CT, computed tomographic; ECG, electrocardiogran1; LAD, left anterior descending; TVD, triple vessel disease; LV, left ventricular; SVD, single vessel disease; DVD, double vessel disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; EF, ejection fraction; ASA, acetyl salicylic acid (aspirin); ACEls, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BBs, beta-blockers; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; DHP, Dihydropyridine; HR, heart rate; BP, blood pressure.

-

•

Short-acting nitrates are indicated for the immediate relief of anginal symptoms (Grade A, Evidence level 2)6, 40, 41

-

•

β-Blockers and/or calcium channel blockers are the initial agents for long-term symptom management and heart rate control based on co-morbidities, contra-indications and patient preference. (Grade A, Evidence level 1)6, 42, 43, 44

-

•

The combination of nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker with β-blockers should be avoided in patients with anticipated risk of atrioventricular block or severe bradycardia. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)45, 46

-

•

The addition of long-acting nitrates or trimetazidine or ivabradine or ranolazine or nicorandil is proposed in case of intolerance or contraindications or failure in achieving angina control by β-blockers and/or calcium channel blockers. The choice of the drug should be made on the basis of blood pressure, heart rate and tolerance. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54

-

•

Ivabradine may be considered in symptomatic patients who do not tolerate beta-blockers or in whom the resting heart rate remains above 70 bpm, despite administration of the full tolerable dose of beta-blockers. [Grade: A, Evidence: 2]51, 55, 56

-

•

When two haemodynamically acting drugs fail to achieve the desired results in reducing angina, preference may be given to cardio-metabolic agents like trimetazidine or ranolazine which has a different mode of action and offers better efficacy in combination with a haemodynamic agent. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)57, 58

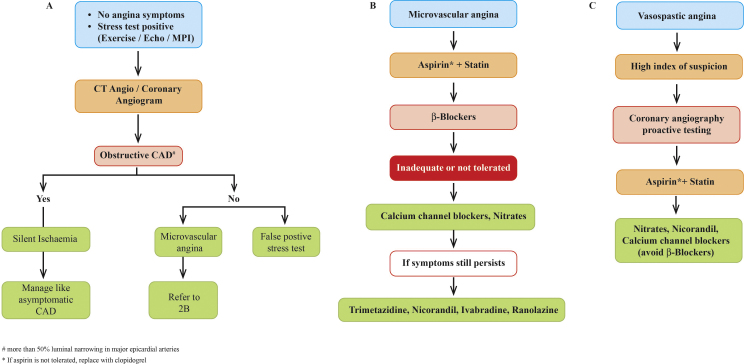

5. Event prevention (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Management of special type of angina. (A) Management of stable angina. (B) Management of microvascular angina. (C) Management of vasospastic angina. Abbreviations: PET, positron emission tomography; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; ECG, electrocardiogram.

-

•

Indefinite daily low-dose aspirin is recommended in all SCAD patients if not contraindicated. (Grade A, Evidence level 1)59, 60, 61

-

•

Clopidogrel is recommended in patients with aspirin intolerance. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)62, 63, 64, 65

-

•

In view of absence of any trial showing the benefit of prasugrel or ticagrelor in stable angina patients and also considering their cost in this sub-set of patients, they may be avoided pending results of the trials addressing this issue. [Grade A, Evidence 4]

-

•

Statin should be prescribed in all patients with SCAD irrespective of lipid levels. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)66

-

•

All stable angina patients with diabetes, hypertension, heart failure or early chronic kidney disease should be recommended to receive angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors if not contra-indicated. (Grade A, Evidence level 1)67, 68, 69, 70

-

•

Rest of the patients with SCAD should also be recommended to receive ACE inhibitors. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)69, 70, 71

-

•

A combination of ACE inhibitors and amlodipine may be considered in hypertensive CAD patients for improving CV outcomes. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)72, 73, 74

-

•

Angiotensin receptor blockers treatment may be used as an alternative therapy for patients who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)75, 76

6. Treatment of certain forms of SCAD

6.1. Silent myocardial ischaemia

-

•

Silent myocardial ischaemia should be managed in the similar lines as symptomatic stable angina and needs administration of anti-ischaemic therapy and revascularisation as required. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)6

-

•

Use of optimal medical therapies such as lipid-lowering agents, β-blockers and metabolic therapies such as trimetazidine or ranolazine can be prescribed after careful examination of the patient according to the individual on a case to case basis. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)77, 78, 79, 80

6.2. Microvascular angina

-

•

Microvascular angina patients can be initially treated with β-blockers in addition to secondary preventive agents including aspirin and statins. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)81, 82, 83

-

•

Calcium channel blockers can be prescribed if β-blockers are inadequate or not tolerated in microvascular angina. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)84, 85, 86

-

•

Novel agents like trimetazidine, ranolazine and ivabradine may be effective in microvascular angina. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)87, 88, 89

6.3. Vasospastic angina

-

•

The treatment of vasospastic angina should be individualised according to the diagnosis of each case. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)6

-

•

Calcium channel blockers can be used for effective prevention of vasospastic angina. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)6, 90, 91

-

•

In patients who continue to be symptomatic agents like trimetazidine, nicorandil, ranolazine and ivabradine may be effective. [Grade A, Evidence 3]

6.4. Revascularisation

-

•

The decision of considering revascularisation in patient with SCAD should be individualised. Revascularisation can be opted early when patients symptoms are uncontrolled by medical therapy alone and/or have high-risk features. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)6

-

•

While selecting whether PCI or CABG for revascularisation, the decision should be purely individualised and consensus based. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)6

The management algorithm of stable coronary artery disease is given in Fig. 1A & B.

The management algorithm of silent myocardial ischaemia, microvascular angina and vasospastic angina is given in Fig. 2A, B & C, respectively.

7. Treatment of special groups of population

7.1. Diabetes

-

•

An objective for HbA1c of <7.0% and blood pressure <140/85 mmHg is recommended for the prevention of microvascular disease in diabetic patients. (Grade A, Evidence level 2)31, 32, 37, 38

-

•

All SCAD patients with diabetes should be recommended to receive an aspirin, high intensity statin and ACE inhibitor or a combination of ACE inhibitor with diuretic if not contraindicated. [Grade A, Evidence 1]21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 92

-

•

For symptomatic treatment of SCAD patients with diabetes, long-acting nitrates or trimetazidine or ivabradine or ranolazine or nicorandil may be considered the first choice as β-blockers are contra-indicated. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)93, 94

-

•

Trimetazidine is particularly beneficial in diabetic multivessel coronary artery disease patients who may also have diffused vessel disease. (Grade A, Evidence level 3)93

-

•

All SCAD patients with diabetes should be treated with Oral Antidiabetics (OADs) which have shown CV safety/benefits such as metformin, gliclazide, gliptins, SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin). (Grade A, Evidence level 2)95, 96, 97, 98, 99

-

•

Revascularisation is recommended in diabetic patients, with persistant symptoms despite optimal medical therapy or high risk features on non-invasive testing. [Grade A, Evidence 4]6, 100

-

•

PCI may be considered in single vessel disease and select cases of multi-vessel disease in consultation with heart team. [Grade A, Evidence 4]6, 100

-

•

Coronary artery bypass grafting can be recommended in high-risk diabetic patients with multi-vessel disease, left main coronary artery disease or in the presence of LV dysfunction. [Grade A, Evidence 4]6, 100

7.2. Chronic kidney disease

-

•

All stable angina patients with chronic kidney disease should be recommended to receive optimal medical therapy. ACE inhibitors can be used if not contra-indicated with careful monitoring of serum creatinine and potassium levels. (Grade A, Evidence level 4)36

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Sharma R., Bhairappa S., Prasad S. Clinical characteristics, angiographic profile and in hospital mortality in acute coronary syndrome patients in south Indian population. Heart India. 2014;2(3):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nag T., Ghosh A. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in Asian Indian population: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4(4):222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalal J., Hiremath M.S., Das M.K. Vascular disease in young Indians (20–40 years): role of ischemic heart disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(9):OE08–OE12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/20206.8517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pryor D.B., Shaw L., McCants C.B. Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(2):81–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancini G.B., Gosselin G., Chow B. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of stable ischemic heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(8):837–849. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montalescot G., Sechtem U., Achenbach S. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(38):2949–3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silveira A.D., Ribeiro R.A., Rossini A.P. Association of anemia with clinical outcomes in stable coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19:21–26. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3282f27c0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz P.E., Li J., Lindstrom J., Tuomilehto J. Tools for predicting the risk of type 2 diabetes in daily practice. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:86–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1087203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Angelantonio E., Danesh J., Eiriksdottir G. Renal function and risk of coronary heart disease in general populations: new prospective study and systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rydén L., Grant P.J., Anker S.D. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Eur Heart J. 2013;34(39):3035–3087. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartnik M., Ryden L., Malmberg K. Euro Heart Survey I. Oral glucose tolerance test is needed for appropriate classification of glucose regulation in patients with coronary artery disease: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Diabetes and the Heart. Heart. 2007;93:72–77. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.086975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz Ortiz M., Romo E., Mesa D. Prognostic value of resting heart rate in a broad population of patients with stable coronary artery disease: prospective single-center cohort study. Rev Esp Cardiol Engl Ed. 2010;63(11):1270–1280. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz A., Bourassa M.G., Guertin M.C. Long-term prognostic value of resting heart rate in patients with suspected or proven coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(10):967–974. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palatini P. Heart rate: a strong predictor of mortality in subjects with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(10):943–945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gianrossi R., Detrano R., Mulvihill D. Exercise-induced ST depression in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. A meta-analysis. Circulation. 1989;80:87–98. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw L.J., Mieres J.H., Hendel R.H. Comparative effectiveness of exercise electrocardiography with or without myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography in women with suspected coronary artery disease: results from the What is the Optimal Method for Ischemia Evaluation in Women (WOMEN) trial. Circulation. 2011;124:1239–1249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He J., Vupputuri S., Allen K. Passive smoking and the risk of coronary heart disease – a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(12):920–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903253401204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boffetta P., Straif K. Use of smokeless tobacco and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3060. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta R., Gupta N., Khedar R.S. Smokeless tobacco and cardiovascular disease in low and middle income countries. Indian Heart J. 2013;65(4):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer F., Kraemer A. Meta-analysis of the association between second-hand smoke exposure and ischaemic heart diseases. COPD and stroke. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1202. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perk J., De Backer G., Gohlke H. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur Heart J. 2012;33(13):1635–1701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misra A., Chowbey P., Makkar B.M. Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudeja V., Misra A., Pandey R.M. BMI does not accurately predict overweight in Asian Indians in northern India. Br J Nutr. 2001;86(1):105–112. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra A., Pandey R.M., Sinha S. Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis of body fat & body mass index in dyslipidaemic Asian Indians. Indian J Med Res. 2003;117:170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vikram N.K., Misra A., Pandey R.M. Anthropometry and body composition in northern Asian Indian patients with type 2 diabetes: receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis of body mass index with percentage body fat as standard. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2003;16:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh K.D., Dhillon J.K., Arora A., Gill B.S. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of BMI and percentage body fat in type 2 diabetics of Punjab. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;48(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baigent C., Keech A., Kearney P.M. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebrahimi R., Saleh J., Toggart E. Effect of preprocedural statin use on procedural myocardial infarction and major cardiac adverse events in percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20(6):292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorresteijn J.A., Boekholdt S.M., van der Graaf Y. High-dose statin therapy in patients with stable coronary artery disease: treating the right patients based on individualized prediction of treatment effect. Circulation. 2013;127(25):2485–2493. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enas E.A., Kuruvila A., Khanna P. Benefits & risks of statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in Asian Indians – a population with the highest risk of premature coronary artery disease & diabetes. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(4):461–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansson L., Zanchetti A., Carruthers S.G. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanchetti A., Grassi G., Mancia G. When should antihypertensive drug treatment be initiated and to what levels should systolic blood pressure be lowered? A critical reappraisal. J Hypertens. 2009;27:923–934. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832aa6b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L., Zhang Y., Liu G. The Felodipine Event Reduction (FEVER) Study: a randomized long-term placebo-controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2157–2172. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000194120.42722.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber M.A., Julius S., Kjeldsen S.E. Blood pressure dependent and independent effects of antihypertensive treatment on clinical events in the VALUE Trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2049–2051. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bicket D.P. Using ACE inhibitors appropriately. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(3):461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonyl ureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel A., MacMahon S., Chalmers J. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piepoli M.F., Hoes A.W., Agewall S., Authors/Task Force Members 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ISIS-4: a randomised factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium sulphate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. ISIS-4 (Fourth International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1995;345(March (8951)):669–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savonitto S., Motolese M., Agabiti-Rosei E. Antianginal effect of transdermal nitroglycerin and oral nitrates given for 24 hours a day in 2,456 patients with stable angina pectoris. The Italian Multicenter Study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;33(4):194–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies R.F., Habibi H., Klinke W.P. Effect of amlodipine, atenolol and theircombination on myocardial ischemia during treadmill exercise and ambulatorymonitoring. Canadian Amlodipine/Atenolol in Silent Ischemia Study (CASIS) Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:619–625. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00436-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein W.W., Jackson G., Tavazzi L. Efficacy of monotherapy compared with combined antianginal drugs in the treatment of chronic stable angina pectoris: a meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis. 2002;13(8):427–436. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mishra S. Does modern medicine increase life-expectancy: Quest for the Moon Rabbit? Indian Heart J. 2016;68:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mills T.A., Kawji M.M., Cataldo V.D. Profound sinus bradycardia due to diltiazem, verapamil, and/or beta-adrenergic blocking drugs. J La State Med Soc. 2004;156(6):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeltser D., Justo D., Halkin A. Drug-induced atrioventricular block: prognosis after discontinuation of the culprit drug. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thadani U., Fung H.L., Darke A.C. Oral isosorbidedinitrate in angina pectoris: comparison of duration of action an dose–response relation during acute and sustained therapy. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:411–419. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chrysant S.G., Glasser S.P., Bittar N. Efficacy and safety of extended-release isosorbide mononitrate for stable effort angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90292-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Vries R.J., Dunselman P.H., van Veldhuisen D.J. Comparison between felodipine and isosorbide mononitrate as adjunct to beta blockade in patients > 65 years of age with angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(12):1201–1206. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Effect of nicorandil on coronary events in patients with stable angina: the Impact of Nicorandilin Angina (IONA) randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08265-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tardif J.C., Ford I., Tendera M. Efficacy of ivabradine, a new selective I(f) inhibitor, compared with atenolol in patients with chronic stable angina. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2529–2536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tardif J.C., Ponikowski P., Kahan T. Efficacy of the I(f) current inhibitor ivabradine in patients with chronic stable angina receiving beta-blocker therapy: a 4-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:540–548. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson S.R., Scirica B.M., Braunwald E. Efficacy of ranolazine in patients with chronic angina observations from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled MERLIN-TIMI (Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes) 36 Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1510–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Clinical Guidelines Centre . 2011. Stable Angina: Management. Clinical guideline [CG126]https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg126/evidence/full-guideline-183176605 Available from: [accessed 07.11.16] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fox K., Ford I., Steg P.G. Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9641):817–821. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amosova E., Andrejev E., Zaderey I. Efficacy of ivabradine in combination with Beta-blocker versus uptitration of Beta-blocker in patients with stable angina. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2011;25(6):531–537. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson G. Combination therapy in angina: a review of combination haemodynamic treatment and the role of combined haemodynamic and cardio-metabolic agents. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55(4):256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chazov E., Lepakchin V., Zharova E. Trimetazidine in Angina Combination Therapy-the TACT study: trimetazidine versus conventional treatment in patients with stable angina pectoris in a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Am J Ther. 2005;12(1):35–42. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juul-Moller S., Edvardsson N., Jahnmatz B. Double-blind trial of aspirin in primary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with stable chronic angina pectoris. The Swedish Angina Pectoris Aspirin Trial (SAPAT) Group. Lancet. 1992;340:1421–1425. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92619-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berger J.S., Brown D.L., Becker R.C. Low-dose aspirin in patients with stable cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2008;121(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.CAPRIE Steering Committee A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhatt D.L., Chew D.P., Hirsch A.T. Superiority of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with prior cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2001;103(3):363–368. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ringleb P.A., Bhatt D.L., Hirsch A.T., Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events Investigators Benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin is amplified in patients with a history of ischemic events. Stroke. 2004;35(2):528–532. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110221.54366.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schiano P., Steg P.G., Barbou F. A strategy for addressing aspirin hypersensitivity in patients requiring urgent PCI. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1(1):75–78. doi: 10.1177/2048872612441580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cannon C.P., Steinberg B.A., Murphy S.A. Meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(3):438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. The SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfeffer M.A., Braunwald E., Moye L.A. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J. Effects of anangiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fox K.M. EURopean trial On reduction of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease Investigators. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study) Lancet. 2003;362(9386):782–788. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al-Mallah M.H., Tleyjeh I.M., Abdel-Latif A.A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in coronary artery disease and preserved left ventricular systolic function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(8):1576–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bertrand M.E., Ferrari R., Remme W.J. Clinical synergy of perindopril and calcium-channel blocker in the prevention of cardiac events and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Post hoc analysis of the EUROPA study. Am Heart J. 2010;159(5):795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dahlof B., Sever P.S., Poulter N.R. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jamerson K., Weber M.A., Bakris G.L. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yusuf S., Teo K.K., Pogue J. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1547–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mann J.F., Schmieder R.E., McQueen M. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9638):547–553. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuralay E., Demirkiliç U., Özal E. Myocardial ischemia after coronary bypass: comparison of Trimetazidine and Diltiazem. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 1999;7(2):84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kikalishvili T.T., Chumburidze V.B., Kurashvili R.B. P-459: exercise-induced and silent ischemia: different effects of monotherapy. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(S1):185A. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marazzi G., Wajngarten M., Vitale C. Effect of free fatty acid inhibition on silent and symptomatic myocardial ischemia in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu X., Zhang W., Zhou Y. Effect of trimetazidine on recurrent angina pectoris and left ventricular structure in elderly multivessel coronary heart disease patients with diabetes mellitus after drug-eluting stent implantation: a single-centre, prospective, randomized, double-blind study at 2-year follow-up. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(4):251–258. doi: 10.1007/s40261-014-0170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bugiardini R., Borghi A., Biagetti L. Comparison of verapamil versus propranolol therapy in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(5):286–290. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lanza G.A., Colonna G., Pasceri V. Atenolol versus amlodipine versus isosorbide-5-mononitrate on anginal symptoms in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(7):854–856. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marinescu M.A., Loffler A.I., Ouellette M. Coronary microvascular dysfunction, microvascular angina, and treatment strategies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(2):210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cannon R.O., 3rd, Watson R.M., Rosing D.R. Efficacy of calcium channel blocker therapy for angina pectoris resulting from small-vessel coronary artery disease and abnormal vasodilator reserve. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56(4):242–246. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90842-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ozcelik F., Altun A., Ozbay G. Antianginal and anti-ischemic effects of nisoldipine and ramipril in patients with syndrome X. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(5):361–365. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960220513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang L., Cheng Z., Gu Y. Short-term effects of verapamil and diltiazem in the treatment of no reflow phenomenon: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:382086. doi: 10.1155/2015/382086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nalbantgil S., Altintiğ A., Yilmaz H. The effect of trimetazidine in the treatment of microvascular angina. Int J Angiol. 1999;8(1):40–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01616842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rogacka D., Guzik P., Wykretowicz A. Effects of trimetazidine on clinical symptoms and tolerance of exercise of patients with syndrome X: a preliminary study. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11(2):171–177. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Villano A., Di Franco A., Nerla R. Effects of ivabradine and ranolazine in patients with microvascular angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sueda S., Kohno H., Fukuda H. Limitations of medical therapy in patients with pure coronary spastic angina. Chest. 2003;123:380–386. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina) (JCS 2008): digest version. Circ J. 2010;74:1745–1762. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-74-0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Investigators HOPE Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Lancet. 2000;355(9200):253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Belardinelli R., Cianci G., Gigli M. Effects of trimetazidine on myocardial perfusion and left ventricular systolic function in type 2 diabetic patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51:611–615. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31817bdd66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shehata M. Cardioprotective effects of oral nicorandil use in diabetic patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J Interv Cardiol. 2014;27(5):472–481. doi: 10.1111/joic.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lavrenko A.V., Kutsenko L.A., Solokhina I.L. [Efficacy of metformin as initial therapy in patients with coronary artery disease and diabetes type 2] Lik Sprava. 2011;(1–2):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schramm T.K., Gislason G.H., Vaag A. Mortality and cardiovascular risk associated with different insulin secretagogues compared with metformin in type 2 diabetes, with or without a previous myocardial infarction: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2013;32(15):1900–1908. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hong J., Zhang Y., Lai S. Effects of metformin versus glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1304–1311. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zinman B., Lachin J.M., Inzucchi S.E. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1094. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1600827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.White W.B., Cannon C.P., Heller S.R., EXAMINE Investigators Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1327–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Singh M., Arora R., Kodumuri V. Coronary revascularization in diabetic patients: current state of evidence. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2011;16(1):16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]