The repetition suppression effect may help probe for individual differences in habituation to a stimulus conveying fear features.

The recent report in PNAS by Ishai et al. (1) is part of a growing corpus of literature that establishes the privileged status of emotional stimuli for the brain. Stimuli that convey emotion command attention and enjoy enhanced processing in a distributed network of brain regions that represents different features of the stimulus and options for responding to such stimuli (2). There are two findings in the Ishai et al. article that are consistent with this framework: (i) subjects respond more quickly and more accurately to fear relative to neutral targets; and (ii) in all face-responsive regions of interest in the brain (see Fig. 1), fear faces were associated with relatively greater activation than neutral faces were during several phases of the experiment, including during initial encoding of the stimuli, in response to the first match of the target to the memoranda, and in response to the distracter stimuli. These findings are consistent with the notion that stimuli of affective import command extensive resources and are strongly and broadly represented in the brain. The third major observation reported by Ishai et al. is their featured finding, and it is somewhat counterintuitive. They find that in all face regions of interest repetition of fearful targets was associated with stronger suppression effects than repetition of neutral targets was. In other words, activation levels were found to decrease more with repetition of attended fear faces than attended neutral faces. Furthermore, neither fear nor neutral distracters were associated with repetition suppression. In this Commentary, we first discuss some empirical and methodological features of the experiment that is reported and then highlight some important implications of these data and raise questions for future research.

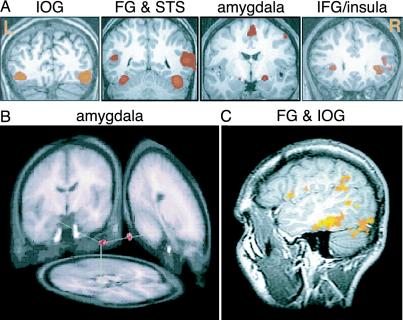

Fig. 1.

The distributed representation of visual emotional stimuli in the human brain. (A) The network of face-responsive regions examined by Ishai et al. (1) displayed as coronal sections, showing activation in the inferior occipital gyri (IOG), fusiform gyrus (FG) and superior temporal sulcus (STS), extended amygdala, and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG)/insula. (B) Amygdala regions of interest (in red) that we have shown to be differentially responsive to affective visual stimuli and psychopathology (from ref. 16). (C) Cortical regions commonly associated with viewing emotional compared with neutral faces. Depicted is a sagittal view of significant activation (Z > 4.2) in FG (lower left cluster) and IOG (lower right cluster) from a representative individual in response to angry compared with neutral faces (unpublished observations).

Methodological Issues in the Study of the Neural Correlates of Facial Expressions of Emotion

One of the very difficult methodological issues in research on emotion that uses facial expressions is the construction of appropriate facial stimuli. Ishai et al. (1) photographed actors who portrayed neutral and fearful expressions and then had an independent group of subjects judge these faces on a five-point scale ranging from not fearful to very fearful. Only faces rated as a four or five were included as stimuli in the experiment. One of the things we do not know is the extent to which voluntarily posed expressions of this kind actually resemble facial signs of fear that are expressed spontaneously in response to fear-provoking stimuli, and it is possible that some fraction of Ishai et al.'s stimuli does not resemble objectively coded posed expressions of fear (refs. 3–5 and see also http://www-2.cs.cmu.edu/~face/). We have preciously few data in the scientific corpus on what the spontaneous facial expression of fear looks like in response to naturalistic elicitors of fear. Most of what we have learned and studied about the neural circuitry responsible for processing facial signs of fear is derived from the prototype of fear that was described by Ekman, Friesen, and Hager (3) and represented in the widely used posed expression of fear reflected in the images from their library.

It is very likely that spontaneous expressions of fear look quite different from such posed expressions (6, 7) and, compared with other facial displays (e.g., happiness, disgust), occur relatively infrequently in everyday life (6). Consequently, fear displays may be treated as novel, ambiguous, or odd. Thus, the differences in reactivity to posed expressions of fear may be a function of several different processes that operate in parallel, including the expression of fear per se, the novelty of the posed variant of this expression (which may differ considerably from spontaneous expressions), and the relative frequency with which such expressions are encountered in the real world (compare effects driven by word frequency). Each of these factors may play a key role in modulating neural and behavioral responsivity to fear expressions. Additionally, the degree to which results such as those reported by Ishai et al. (1) are specific to fear or generalize to other emotional expressions remains unknown.

Another interesting aspect of their data that bears on the privileged status of emotional stimuli is the fact that the second and third repetitions of the fear distracters evoked activations of comparable magnitude and, in some regions, of an even higher magnitude, than activations to the second and third repetitions of the fear targets did. This pattern of observations may reflect the suppression effects observed in response to fear faces and/or the privileged processing of fear faces irrespective of the attentional focus of the subjects. Of course, from this experiment alone, it is impossible to adjudicate between these interpretations. There are currently strong proponents of each side of the view concerning the necessity of attentional resources for the representation of affective information (8–10).

Implications

However this last issue is ultimately resolved, the findings from the Ishai et al. (1) report underscore the profound alterations in responsivity to fear faces that occur with repetition. It is noteworthy that these stimuli elicit more robust responses at encoding and in response to the first repetition, compared with neutral faces. The suppression effect may reflect an adaptive strategy used by the brain to decrease metabolic demands and sharpen cortical processing. Whether repetition suppression in face-responsive regions represents active inhibition or the rapid disengagement of biasing signals originating from other territories, such as the extended amygdala (i.e., amygdala and the more dorsal bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and substantia innominata) or prefrontal cortex, is something that needs to be explored in future research. In combination with the work of Ishai et al., such studies would begin to provide a mechanistic underpinning for hypotheses (11) concerning how and why visual cortical regions commonly exhibit robust activation to emotional compared with neutral stimuli (see Fig. 1).

Also of great interest in the future will be the study of individual differences in the magnitude of the suppression effect in response to fear faces. It is well known that patients with various psychiatric disorders show abnormalities in the time course of emotional responding after the presentation of an aversive stimulus (12–14). Such individual differences likely play a role in vulnerability to mood and anxiety disorders and possibly other illnesses as well (13). The repetition suppression effect described by Ishai et al. (1) in response to fear faces may well be an effective probe for individual differences in specific habituation to a stimulus conveying fear features. Future research should examine whether individual differences in repetition suppression in response to fear faces in the face-responsive regions identified in that article predict other measures of anxiety and mood across subjects. Individuals who show minimal repetition suppression in response to fear faces would be expected to show increased levels of anxiety on behavioral and peripheral biological measures (14). In recent work from our laboratory, individual differences in both baseline metabolic rate in the amygdala assessed with positron emission tomography (15) and stimulus-elicited activation in the amygdala in response to aversive images show excellent test-retest reliability,† a psychometric property requisite for them to be conceptualized as trait-like indices. It will be of great interest to determine whether comparable test-retest reliabilities are obtained for repetition suppression effects in response to fear faces in face-selective regions.

In conclusion, the dynamic change in activation in response to signals of danger such as fear faces is a robust characteristic of neural circuits implicated in face processing and emotion. In response to fear faces, subjects exhibit more of such repetition suppression compared with responses to neutral faces. Although there are some empirical issues that remain to be addressed to better understand the nature of this phenomenon, it does simultaneously underscore the privileged status of emotional processing in the human brain and the fact that the brain normally adapts to affective stimuli such that when the affective cues are no longer providing novel information of relevance to the organism's survival, the resources dedicated to processing that stimulus decline. Of great interest for the future will be to use this paradigm to examine the nature of individual differences in repetition suppression. Individuals who do not show normal patterns of repetition suppression in response to fear faces and other aversive social cues may be particularly vulnerable to mood and anxiety disorders. These findings will help to place endophenotypic descriptions of temperament, personality, and psychopathology on a firmer neural footing.

See companion article on page 9827 in issue 26 of volume 101.

Footnotes

Johnstone, T., Somerville, L. H., Nitschke, J. B., Alexander, A. L., Davidson, R. J., Kalin, N. H. & Whalen, P. J. (2003) NeuroImage 19, S21 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Ishai, A., Pessoa, L., Bikle, P. C. & Ungerleider, L. G. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9827-9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolls, E. T. (1999) The Brain and Emotion (Oxford Univ. Press, New York).

- 3.Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V. & Hager, J. C. (2002) Facial Action Coding System (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London).

- 4.Cohn, J. F. & Kanade, T. (2004) in The Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment, eds. Coan, J. A. & Allen, J. J. B. (Oxford Univ. Press, New York), in press.

- 5.Davidson, R. J., Shackman, A. J. & Maxwell, J. S. (2004) Trends Cognit. Sci., in press.

- 6.Rozin, P. & Cohen, A. B. (2003) Emotion 3, 68-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekman, P., Campos, J., Davidson, R. J. & De Waals, F., eds. (2003) Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years After Darwin's the Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (New York Acad. Sci., New York). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Pessoa, L. & Ungerleider, L. G. (2004) Prog. Brain Res. 144, 171-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolan, R. & Vuilleumier, P. (2003) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 985, 348-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson, A. K., Christoff, K., Panitz, D. A., DeRosa, E. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 5627-5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phan, K. L., Wager, T., Taylor, S. F. & Liberzon, I. (2002) NeuroImage 16, 331-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson, R. J. & Irwin, W. (1999) Trends Cognit. Sci. 3, 11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson, R. J. (2000) Am. Psychol. 55, 1196-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson, R. J. (2002) Biol. Psychiatry 51, 68-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer, S. M., Abercrombie, H. C., Lindgren, K. A., Larson, C. L., Ward, R. T., Oakes, T. R., Holden, J. E., Perlman, S. B., Turski, P. A. & Davidson, R. J. (2000) Hum. Brain Mapp. 10, 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irwin, W., Anderle, M. J., Abercrombie, H. C., Schaefer, S. M., Kalin, N. H. & Davidson, R. J. (2004) NeuroImage 21, 674-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]