Abstract

Background

Diabetes and cancer are public health issues worldwide; studies have shown that diabetes is related to increased breast cancer mortality. The purpose of this study was to examine associations between HbA1C and obesity with tumor stage and mortality among breast cancer patients.

Methods

Data for 82 patients with breast cancer (36–89 years of age, diagnosed /treated 1999–2009) were provided by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Data Trust Warehouse. Survival time was estimated from start date of service to date of last follow-up or date of death. The Kaplan–Meier method provided analysis of survival curves for two groups of HbA1C (HbA1C < 6.5% vs HbA1C ≥ 6.5%) and two groups of BMI (BMI < 30 vs BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2); survival curves were compared using log-rank tests. Associations between HbA1C and BMI, and between HbA1C and tumor stage were determined by chi-square.

Results

The relationship between tumor stages and HbA1C was not statistically significant (X2 = 0.093, p = 0.47, df = 1). The relationship between obesity and HbA1C was statistically significant (X2 = 6.13, p = 0.013, df = 1). Log-rank tests did not show statistically significant differences between survival curves (HbA1C curves, p = 0.4; Obesity curves, p = 0.09).

Conclusion

While there was a statistically significant association between HbA1C and obesity, there were no significant associations found with this analysis. However, there are clinically meaningful relationships based on observed trends. Future directions for research may involve exploring a larger sample of patients and the role of therapeutic regimens on blood sugar control and BMI of breast cancer patients and influence on cancer prognosis.

Keywords: Breast cancer, HbA1C, Diabetes, Tumor stage, Obesity

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor among women, and of all cancers, it is the second leading cause of mortality in women in the US. Estimates for 2016 predicted that 246,660 women were likely to be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and that 40,450 women were likely to die from breast cancer [1]. The rate of mortality from breast cancer has declined due to improvements in early detection and treatment [1]. Early detection of the cancer and evaluation of comorbidities result in prompt and relevant treatment that improves breast cancer survival and ultimately saves lives.

Type 2 diabetes may increase the risk of cancer [2], [3], [4], [5], is considered a common comorbidity present in a considerable number of breast cancer patients and correlates with poor clinical outcomes [6], [7], [8], [9]. Furthermore, diabetes may alter the efficacy of treatment in breast cancer patients affecting drug response and survival endpoints [8], [10], [11], [12]. Therefore understanding the associations between diabetes and cancer development will contribute toward improving cancer screening and assessment practices. The aim of this study was to examine associations between HbA1C and obesity with tumor stage and mortality among breast cancer patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Data for this project came from i2b2 (informatics for integrating biology and the bedside), a large computerized data base at UAMS [13].The dataset consisted of de-identified secondary data and was exempt from review by the UAMS Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.2. .Study population

A cohort was formed including subjects diagnosed with breast during the years of 2001–2009. African-American (AA) and Caucasian women who were ≥ 18 years of age at diagnosis, and who had at least one HbA1C on file were included. Subjects with documented pathological tumor stage, BMI and dates of first and last clinic visits were included in the cohort. Subjects were registered at the oncology clinic. The first visit was defined as the date the patient started service at the clinic and the last follow-up was defined as the last visit. Life /death status was defined according to the Social Security Death Index updated in 2013.

2.3. HbA1C, BMI and tumor stage classification

HbA1C was classified in two groups (normal versus high) with a cut-point value of 6.5% [14], [15]. BMI was classified into 2 groups; non-obese was defined as BMI < 30 kg/m2 and obese was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Tumor stage was classified as low or high based on the TNM classification system (low stages 0–I; high stages II–III) [16].

2.4. Data analysis and statistics

Descriptive statistics including frequencies were used to describe study participant characteristics including age, BMI, HbA1C levels, and tumor stage.

The Kaplan–Meier method provided descriptive analysis of survival curves for the two HbA1C groups and for two BMI groups (BMI < 30 versus BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2); survival curves were compared using log-rank tests. Associations between HbA1C and other variables including BMI and tumor stage were determined by chi-square test. All statistical analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA), Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., LaJolla, CA), and IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) software.

3. Results

The characterization of the studied population is shown in Table 1. The age of the study population ranged from 36 to 89 years (mean = 60). Sixty-two subjects were ≥ 50 years of age (categorized as post-menopausal) and 20 were < 50 years of age (categorized as pre-menopausal). The study population consisted of 56% Caucasian and 41.5% AA women.

Table 1.

Characterization of the studied population.

| Number (%) | Mean (± SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 50 | 20 (24) | 60 |

| ≥ 50 | 62 (76) | |

| Total | 82 (100) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 46 (56) | |

| African American | 36 (44) | |

| BMI | ||

| < 30 | 40 (49) | 25.6 (± 2.72) |

| ≥ 30 | 42 (51) | 37.3 (± 5.7) |

| Total | 82 (100) | 31.7 (± 7.5) |

| Hb1Ac | ||

| < 6.5 | 46 (55) | 5.7 (± 0.5) |

| ≥ 6.5 | 36 (45) | 8.3 (± 2.6) |

| Total | 82 (100) | 6.9 (± 2.2) |

| Tumor stage | ||

| Stage 0 | 13 (16) | |

| Stage I | 28 (34) | |

| Stage II | 27 (33) | |

| Stage III | 14 (17) | |

| Low stage (Stages 0 & I) | 38 (46.3) | |

| High stage (Stages II & III) | 44 (53.7) |

BMI of the study population ranged from 18.73 kg/m2 to 53.81 kg/m2 (mean = 31.72 ± 7.5 kg/m2). Forty-two subjects (51.2%) were classified as obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), and 40 (48.8%) were non-obese (BMI < 30 kg/m2). The levels of HbA1C varied from 4.8% to 17% with a mean of 6.9%. Forty-six subjects (54.9%) were grouped into the normal HbA1C category (< 6.5%) and 36 (45.1%) were grouped into the high HbA1C category (≥ 6.5%).

Thirty-eight subjects were categorized as having low stage tumors (46.3%) and 44 were categorized with high stage tumors (53.7%). A Chi-square test indicated no significant association between HbA1C category and tumor stage (x2 = 0.093, p = 0.47, df = 1).

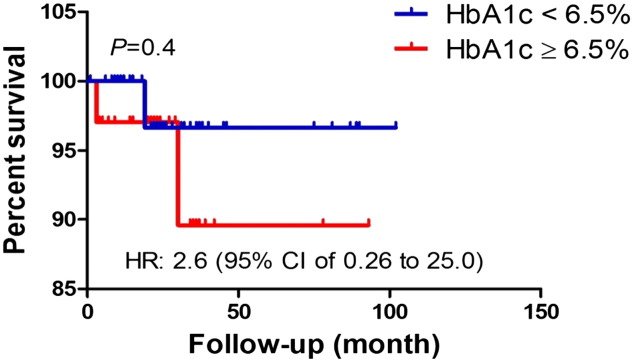

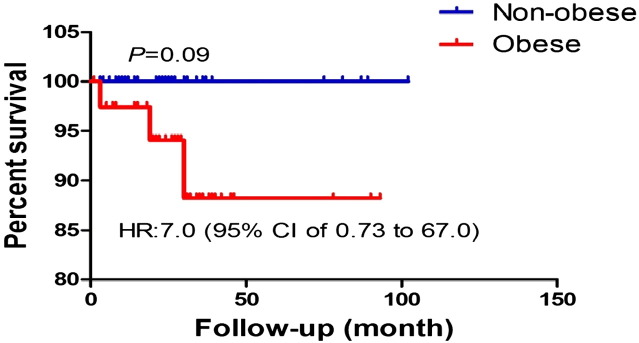

We further examined the association of high HbA1C on tumor survival. The Kaplan–Meier method provided descriptive analysis of survival curves for the two HbA1C groups (Fig. 1) and for the two BMI groups (Fig. 2). Survival curves were compared using log-rank tests, which determined there were no statistically significant differences between survival curves (HbA1C curves, p = 0.4; Obesity curves, p = 0.09).

Fig. 1.

Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier method. Log rank test was used to statistically compare the curves and p value is shown.

Fig. 2.

Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier method. Log rank test was used to statistically compare the curves and p value is shown.

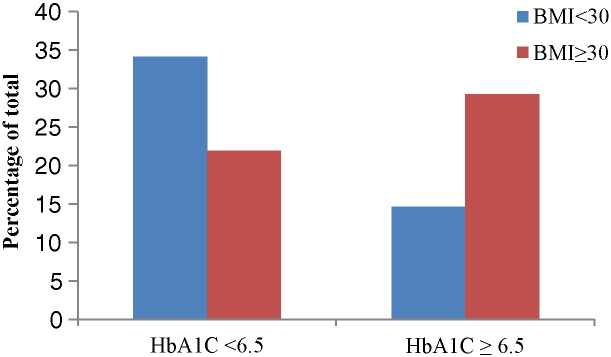

Result of chi-square analysis (Table 2) testing the association between obesity and HbA1C was statistically significant (X2 = 6.126, p = 0.013, df = 1). The percentage of obese patients is clearly larger in the high HbA1C group compared to normal HbA1C group; the percentage of non-obese patients is lower in high HbA1Cgroup compared to normal HbA1C group (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

The results of Chi-square testing association of HbA1C and BMI.

| Number of patients | Pearson chi-square | p value |

|---|---|---|

| 82 | 6.129 | 0.013⁎ |

HbA1c with cut-point 6.5%, BMI with cut-point 30 kg/m2.

The association of HbA1c and BMI is statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Visual representation chi-square analysis demonstrating the distribution of obese and non-obese patients across high and normal HbA1C groups.

4. Discussion

Diabetes and cancer are two major public health issues worldwide and many studies have shown that diabetes is related to increased cancer mortality [8], [17], [18]. According to a review completed by Long and colleagues [19], many studies have shown dysregulation in cellular metabolism may associate with resistance to cancer treatment drugs. Various factors, including insulin, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), and inflammatory cytokines, may link diabetes to breast cancer mortality. In the study reported here, we examined the association of HbA1C as an indicator of blood glucose control with tumor stage and patient mortality among 82 patients diagnosed with breast cancer. We used tumor stage as an indicator of aggressiveness and did not find a statistically significant association between HbA1C levels and tumor stage. These data suggest that blood glucose control as measured by HbA1C is not associated with cancer stage in this population. Our results contradict other studies showing diabetes correlates with late stage diagnosis [9], [20]. Peairs et al. [9] performed a meta-analysis examining the effect of pre-existing diabetes on outcomes of breast cancer. Among 4 datasets included in their analysis, 3 showed an association between diabetes and diagnosis at late stage. One study did not find an association between diabetes and breast cancer stage. Peairs et al. [9] suggest that a lack of association between diabetes and breast cancer stage could be due to large number of samples with missing stage in the study. However, a study investigating associations between type 2 diabetes and colon cancer found that, despite a negative association between diabetes and survival rate, there was not an association between diabetes and tumor stage [21]. Together, the data suggest that involvement of diabetes with mortality in breast cancer patients may be due to non-breast cancer specific causes.

According to results reported here, there was not a statistically significant difference between survival curves for the different HbA1C groups. Our results are in contrast with Erickson et al., who reported elevated HbA1C levels in plasma was independently associated with higher mortality in breast cancer survivors [20]. Lack of statistical significance in the current study is most likely due to small sample size that results in a low-power study. Despite our small sample size, we observed a potentially clinically relevant decrease in survival of patients with HbA1C ≥ 6.5%. However, such a decrease is not accompanied with high tumor stage, suggesting that deaths could be unrelated to cancer.

As expected, we observed a positive and statistically significant association between obesity and HbA1C, which may suggest the HbA1C groups (≥ 6.5% vs < 6.5%) actually represent individuals with differing mortality risk, and is worth additional investigation involving a larger sample size. Obesity is a major factor associated with type 2 diabetes [22] that may also affect breast cancer survival [23]. Result of the current study leans toward poorer survival in the obese group, which is in harmony with published data [23].

5. Study limitations

Limitations of the current study included a small sample size, and unavailability of prognostic factors and cancer-specific survival data.

6. Conclusions

Breast cancer has a low mortality rate and survivors are living longer; therefore, there is need for studies with a longer follow-up period. Future directions for research may involve exploring a larger sample of patients and the role of therapeutic regimens on blood sugar control and BMI of breast cancer patients and influence on cancer prognosis.

Authors' contributions

Fariba Jousheghany developed the hypothesis and designed the study, organized, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. Josh Phelps contributed to development of the hypothesis and study design, data organization and analysis, and manuscript development. Tina Crook contributed to development of the hypothesis and study design, and manuscript development. Reza Hakkak contributed to development of the hypothesis and study design, and manuscript development.

Funding

This research was supported by Department of Dietetics and Nutrition at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgements

We thank the UAMS Data Warehouse staff for enabling access to data used for this study.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . American cancer society, Inc.; Atlanta: 2016. Breast Cancer Facts & Figs. 2015–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu H.L., Fang H., Xu W.H., Qin G.Y., Yan Y.J., Yao B.D. Cancer incidence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study in Shanghai. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:852. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1887-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vona-Davis L., Rose D.P. Type 2 diabetes and obesity metabolic interactions: common factors for breast cancer risk and novel approaches to prevention and therapy. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2012;8(2):116–130. doi: 10.2174/157339912799424519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saydah S.H., Loria C.M., Eberhardt M.S., Brancati F.L. Abnormal glucose tolerance and the risk of cancer death in the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003;157(12):1092–1100. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferroni P., Riondino S., Buonomo O., Palmirotta R., Guadagni F., Roselli M. Type 2 diabetes and breast cancer: the interplay between impaired glucose metabolism and oxidant stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015;2015:183928. doi: 10.1155/2015/183928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowie C.C., Rust K.F., Ford E.S., Eberhardt M.S., Byrd-Holt D.D., Li C. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cazzaniga M., Bonanni B., Guerrieri-Gonzaga A., Decensi A. Is it time to test metformin in breast cancer clinical trials? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009;18(3):701–705. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipscombe L.L., Goodwin P.J., Zinman B., McLaughlin J.R., Hux J.E. The impact of diabetes on survival following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;109(2):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peairs K.S., Barone B.B., Snyder C.F., Yeh H.C., Stein K.B., Derr R.L. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(1):40–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coughlin S.S., Calle E.E., Teras L.R., Petrelli J., Thun M.J. Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;159(12):1160–1167. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie C.J., Peyrot M., Morgan C.L., Poole C.D., Jenkins-Jones S., Rubin R.R. The impact of treatment noncompliance on mortality in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1279–1284. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranc K., Jorgensen M.E., Friis S., Carstensen B. Mortality after cancer among patients with diabetes mellitus: effect of diabetes duration and treatment. Diabetologia. 2014;57(5):927–934. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.http://tri.uams.edu/research-resources-services-directory/biomedical-informatics-data-services/electronic-health-care-data-for-research/

- 14.Gillett M.J. International expert committee report on the role of the A1c assay in the diagnosis of diabetes: diabetes care 2009; 32(7): 1327–334. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2009;30(4):197–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen R.M., Haggerty S., Herman W.H. HbA1c for the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes: is it time for a mid-course correction? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95(12):5203–5206. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.breastcancer.org

- 17.Larsson S.C., Mantzoros C.S., Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121(4):856–862. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minicozzi P., Berrino F., Sebastiani F., Falcini F., Vattiato R., Cioccoloni F. High fasting blood glucose and obesity significantly and independently increase risk of breast cancer death in hormone receptor-positive disease. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49(18):3881–3888. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long J.P., Li X.N., Zhang F. Targeting metabolism in breast cancer: how far we can go? World J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;7(1):122–130. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v7.i1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson K., Patterson R.E., Flatt S.W., Natarajan L., Parker B.A., Heath D.D. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(1):54–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyerhardt J.A., Catalano P.J., Haller D.G., Mayer R.J., Macdonald J.S., Benson A.B., 3rd Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21(3):433–440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn S.E., Hull R.L., Utzschneider K.M. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444(7121):840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ligibel J. Obesity and breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25(11):994–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.